Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Pi Is 026661381100180 X

Încărcat de

Nur FadjriDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Pi Is 026661381100180 X

Încărcat de

Nur FadjriDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Midwifery

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/midw

Childbirth at home: A qualitative study exploring perceptions of risk and risk

management among Baloch women in Iran

Zhila Abed Saeedi, RN, MS, PhD (Assistant Professor of Nursing)a, Mahmoud Ghazi Tabatabaie, PhD

(Professor of Sociology and Social Demography of Health)b, Zahra Moudi, RM, MS, MScIH (PhD

Candidate of Reproductive Health)a,n, Abou Ali Vedadhir, PhD (Assistant Professor of Anthropology)b,

Ali Navidian, RN, MS, PhD (Assistant Professor of Consulting Psychology)c

a

b

c

Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Shaheed Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Department of Demography and Population Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 3 May 2011

Received in revised form

25 September 2011

Accepted 6 November 2011

Objective: to explain how women who choose to give birth at home perceive and manage the risks

related to childbirth.

Design: a qualitative, methodological approach drawing upon the principles of grounded theory. Data

were gathered by in-depth interviews with women who had given birth at home.

Setting: the study was conducted in Zahedan, the capital of Sistan and Balochestan province in

southeast Iran.

Participants: 21 Baloch women aged 1339 years who had a planned home birth were interviewed.

Nine had been attended by university-educated midwives, eight by trained midwives, and four by

traditional birth attendants.

Findings: concerning perceived risks, women perceived giving birth in hospital to be risky because of

medical interventions, routines and ethical considerations. The perceived risks for home birth were

acute medical conditions. Women made their decision to give birth at home based on existing verbal,

visual, and intuitive information. The following two categories related to risk management were

identied: (1) psychological preparation and (2) medical and logistican preparation. All of the women

relied on their own intuition, their midwife and the sociopsychological support of their families to

transfer them to hospital in the case of complications.

Key conclusions and implications for practice: the women who chose to give birth at home accepted that

there was a risk of complications, but perceived these to be due to fate. Technical risks were considered

to be a consequence of the decision to give birth in hospital, and were perceived to be avoidable.

In addition, the women considered ethical issues as risks that are sometimes more important than

medical complications. Womens perceptions of risk, and the ways in which they prepare to manage

risk, are central issues to help providers and policy makers adjust services to womens expectations in

order to respond to the individuality of each woman.

& 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Women

Home birth

Risk perception

Risk management

Introduction

Globally, there were around 358 000 maternal deaths occurred

in 2008, a 34 % decline from the levels of 1990 (World Health

Organisation, 2010). However, despite this decline, 99% of maternal deaths continued to occur in developing countries (World

Health Organization, 2010). Nearly two-thirds of maternal deaths

n

Correspondence to: Midwifery Department, Nursing and Midwifery School,

Mashahir Square, Zahedan, Sistan and Baluchestan Province, Iran.

E-mail address: zz_moudi@yahoo.com (Z. Moudi).

0266-6138/$ - see front matter & 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.midw.2011.11.001

worldwide are due to the following direct causes: haemorrhage,

obstructed labour, eclampsia, sepsis, and unsafe abortion. The

remaining one-third of maternal deaths due to indirect causes or

an existing medical condition that is worsened by pregnancy or

childbirth (United Nations Population Fund, 2002). A closer

examination of maternal mortality in Iran shows a rate of

approximately 30 per 100,000 live births (Malekafzali, 2009;

World Health Organization, 2010). Irans Ministry of Health and

Medical Education has implemented several interventions to

reduce maternal mortality. As the vast majority of complications

and deaths arise during and immediately after childbirth, and due

to sudden and unexpected complications (Donnay, 2000), the

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

Ministry of Health and Medical Education has emphasised the

provision of essential obstetric care services and hospital birth.

However, the most recent ofcial data show that 10.8% of

women in urban areas of Sistan and Balochestan province do not

comply with this policy to give birth in hospital (Integrated

Management Evaluation System, 1994). Sistan and Balochestan

province, located in southeast Iran, bordering Pakistan, is among

the most deprived provinces in the country. Zahedan, the setting

for this study, is the capital and the most populous city of this

province (population of 689,444 in 2009). The population of

Zahedan consists of two ethnolinguistic groups Baloch and

Sistani plus Afghan refugees. The Baloch and Sistani ethnolinguistic groups are the indigenous people of the province. The

Baloch people live mainly in Pakistan and Iran, and represent the

majority population in Zahedan. They are typically Sunni Muslim,

the largest Islamic religious group, while non-Baloch inhabitants

of the province are Shiite or Shia.

The population growth rate and total fertility rate in Zahedan

were 2.5% and 3.6%, respectively, for women of reproductive age

in 2009. Fifty-three maternal deaths were reported between 2005

and 2010, 10 of which occurred following a home birth. Childbirth

services in the area include four comprehensive essential obstetric care services and two birth centres. These centres, which are

located in the city suburbs, are managed by qualied midwives

and are open 24 hrs/day. The midwives at these centres assist

with normal vaginal childbirth, but are not allowed to administer

antibiotics to treat infections or anticonvulsants to treat seizures.

They are also banned from removing the placenta manually, and

refer women in this situation to hospital. Despite the availability

of these facilities, 12% of women still choose to give birth at home

attended by a traditional birth attendant, a trained birth attendant or an educated midwife from a private ofce (Maternal

Health Ofce, 2011).

There is wide recognition that a major factor contributing to

maternal mortality is the infrequent use of health facilities for

childbirth (Kanti and Rumsey, 2002; Duong et al., 2004; Berry,

2006; Say and Raine, 2007). A brief review of the literature

suggests that psychological and sociocultural (Steinberg, 1996;

Gabrysch and Campbell, 2009) studies of decision-making have

gained increased attention over the last two decades. In light of

the importance of the decision-making process, many disciplines

have put considerable effort into studying and clarifying decisionmaking (Murphy and Longo, 2009, pp. xixii). The literature, at a

glance, demonstrates that decision-making takes place in and

affects our everyday life in many ways. Firstly, it allows us to

rationalise and choose the most appropriate actions or strategies

for a particular event or task in order to attain the best outcome.

Secondly, it allows us to be exible in an ever-changing world,

reacting quickly to both routine and specic life matters in a

timely manner. Thirdly, it allows us to enhance the chance of

success and minimise the chance of failure (Chan, 2009, p. 21).

The issue of decision-making is not simple, but is closely related

to our culture or styles of knowing and living in a highly reexive

world. Many scholars believe that qualitative approaches should

be considered when exploring the sociocultural and psychological

aspects of decision-making. For example, Chan (2009, pp. 2223)

proposed a 6Rs framework (reference, reexivity, replication,

remarks, reproach, and registration) to ensure good practice in

the preparation and implementation of these studies. In this view,

womens health-related decisions about giving birth at home or in

hospital cannot be an exception, as they are closely intertwined

with the womens daily lives and living conditions, life chances

(structure) and life choices (agency), proposition to act (habitus)

and meaning in life (Bourdieu, 1990, pp. 5355; Cockerham, 2007,

pp. 4974). As Bourdieu reected, the habitus makes possible

the free production of all the thoughts, perceptions, actions

45

inherent in the particular conditions of its production and only

those (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 55). In this view, a womans decision

about her childbirth can be deeply embedded and understood in

the frame of the habitus. Therefore, some scholars have suggested

that a womans decision about her childbirth is affected by her

habitus in general, and her perception or construction of risks

associated with childbirth in particular. In a broad sense, the

notion of risk means different things to different people. Actions

and understanding of risk go beyond the individual, as risk is a

sociocultural construct that reects cultural values, symbols,

history and ideology (Sjoberg, 2004). Moreover, prior life experiences and health-care providers can affect a womans perception

of risk (Jordan and Murphy, 2009). Understanding the determinants of risk perception may provide insight into well-organised

measures to adjust services to womens expectations, as what

suits one person may not suit another (East et al., 2008, p. 167).

Therefore, the current study aims to explain how Iranian Baloch

women who choose to give birth at home rationalise and perceive

it, and how they manage the risks of planned home birth.

Methods

Approach

This study draws methodologically on a qualitative approach.

This methodological approach may be most simply dened as the

techniques associated with the gathering, analysis, interpretation

and presentation of narrative data and/or information. Qualitative

research strategies are narrative in form, and qualitative (thematic) data are analysed using a variety of inductive and iterative

methods, including the grounded theory (Teddlie and Tashakkori,

2009). In considering the nature of research questions and the

purpose of this study, strategies and principles of grounded

theory were used to provide a logical set of procedures to answer

the research questions and manage the collected data and

evidence. The essence of grounded theory is an inductive

deductive interplay that does not begin with a hypothesis, but

with collecting data and allowing relevant ideas to develop

(McGhee et al., 2007). It is also an endeavour to declare the

anthropocentric nature of sociocultural life and its fundamental

interactional processes, as Chenitz and Swanson observe that the

reality or meaning of situation is created by people and leads to

action and consequences of action (Bassett, 2004). This implies

that a set of social or psychological relationships and process exist

in the world, can be reected in appropriate qualitative data, and

can be captured by grounded theory (Pidgeon and Henwood,

2009, p. 627). In this view, grounded theory can promote a better

and more comprehensive understanding of the decision-making

process and management of the risks of home birth by the

participants.

Sample and recruitment

Twenty-one Baloch women with a history of home birth

participated in the study. They were recruited using qualitative

purposeful sampling, which involves making choices about cases

or setting according to initial prespecied criteria (Pidgeon and

Henwood, 2009, p. 635). In order to recruit women with homebirth experience, the researchers contacted four midwives who

had a private ofce and assisted with home births. To identify

women who had given birth at home without the assistance of

educated or professional midwives, the Maternal Health Ofce

was contacted for the name and telephone number of a trained

birth attendant. This birth attendant recruited two additional

traditional birth attendants. The midwives were informed about

46

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

the study and asked to explain its purpose to the women they had

assisted during a home birth within the previous four months.

Women with precipitous labour who were forced to give birth at

home were excluded. The midwives asked women for their

consent, and then their telephone numbers were given to the

interviewer. The interviewer contacted the women and asked for

their informed consent to participate in the study. If the women

agreed to participate, a mutually agreeable appointment was

scheduled.

In addition, a theoretical sampling technique was used. In

conjoint with constant comparison, theoretical sampling is the

process whereby the researcher decides what data to collect next

and where to nd them in order to continue to develop theory as it

emerges (Holton, 2007, p. 627). Researchers deliberately seek

participants who had a particular response to experiences or for

whom particular concepts appear signicant (Morse, 2007, p. 240).

The sampling process ceased once comparative data analysis

showed that maximum theoretical variation had been achieved,

namely the saturation rule (Pidgeon and Henwood, 2009, p. 635).

In other words, the researchers were convinced that they understood what they were seeing, it was culturally consistent (Morse,

2007, p. 243), and new ideas would not be formed leading to a

dilemma (Bassett, 2004, p. 64). Twenty-one Baloch women who

had a planned home birth were interviewed. Of these women, nine

were attended by an educated midwife, eight by a trained midwife

and four by a traditional birth attendant. Of the 21 participants,

two women participated with their husbands; 16 participated

with their mother, mother-in-law or sister; and three participated

alone.

Data collection

Data were gathered through in-depth, unstructured interviews

in the participants homes. The interviews lasted between one

and 3 hrs. An unstructured interview was conducted to collect

data on the subject of risk related to home birthwhat did the

women think about probable risks related to childbirth at home?

Further open-ended questions built upon the womens responses

to the questions and further clarications or details of their

responses and the complete narrative; for example, how did

you handle these thoughts? How did your husband react to your

decision? All interviews were conducted in Persian with a slight

Baloch accent by one of the investigators who has a Baloch

background. The interviewees were reminded of their right to

withdraw from the study at any time. All interviews were audio

taped, transcribed verbatim and analysed.

Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Shaheed

Beheshti University of Medical Sciences Ethical Committee and

relevant local authorities in Sistan and Balochestan province. The

investigators obtained the participants permission to perform and

audio tape the interviews. The condentiality of information was

guaranteed, as the name and personal information of the interviewees was not mentioned in the tapes or transcripts. All tapes,

transcripts and information sheets were given special codes and

kept separately to protect the womens anonymity.

Data analysis

In line with grounded theory methodology, data analysis

involved the complementary process of coding and categorising

data, and developing analytical questions and a conceptual model.

Following the transcription of the rst tape, the rst step was

line-by-line reading and open coding of the data, based on the

principles of grounded theory. Data coding was undertaken by the

primary researcher (midwife), a counselling psychologist and a

qualitative sociologist. Open coding refers to reading the transcript and naming or coding each line of text (Gibbs, 2007, p. 52).

Some of participants were given the transcript and codes to

conrm them or add comments. In order to gain greater insight,

two Baloch birth attendants (a qualied midwife and a trained

birth attendant) who helped women with home birth were asked

to review the transcripts and help with interpretations. The

constant comparison helped to identify the meaning behind the

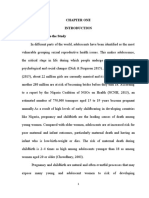

surface text. Subsequently, the investigators shifted from description, especially using the respondents terms, to a more categorical level of coding (Gibbs, 2007, p. 42). Fig. 1 shows the

categories and subcategories that emerged through the process

of data analysis. Finally, all of the ndings were presented to ve

midwives and four mothers who were not participating in the

study for critical assessment.

Findings

Twenty-one Baloch women aged 1339 years were interviewed. They had previously experienced 18 pregnancies. One

of them was illiterate and the education level of the others

ranged from elementary to high school national diploma. Previous

childbirth locations, parity, previous types of childbirth, and the

insurance status of the women are presented in Table 1. Regarding

the risks of home birth, two central themes emerged: perceptions

of risk and management of that risk. In terms of perceived

risks, women perceived giving birth in hospital to be risky

because of medical interventions, routines and ethical considerations. The perceived risks of home birth were acute medical

conditions. Categories related to risk management were as follows: psychological preparation, and medical and logistic

preparation.

Perceptions of risk

Perceptions of medical risks

The Baloch womens statements revealed that they did not

perceive chronic conditions to be a risk factor or a good reason to

visit a doctor. One of the women stated:

They told me, in the birth centre, that I was suffering from

severe anaemia and I should see a doctor; I replied that I have

had this problem for a long time and it is normal for me and

I do not think that something bad would happen to me.

(Interviewee 7, age 25 years).

Later in the interview, Interviewee 7 stated:

In the health centre, I was told: if you have massive bleeding

during labour you will probably die, but I had anaemia during

my previous delivery and you see I did not die. (Interviewee 7,

age 25 years).

In addition, other women did not consider the presence of a

chronic disease to be a reason to give birth in hospital:

She told me that my blood pressure was high (130 mmHg) and

I had to have a hospital birth, but during my last pregnancy,

my blood pressure was also 130 mmHg and I had home birth

without any problem. So, this time I also had a home birth and

refused to go to the hospital. (Interviewee 14, age 29 years).

The women considered acute signs (e.g. loss of consciousness)

to be an indication that they should attend hospital. The women

also considered their previous knowledge about the risk of

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

47

Socio, cultural and economic context

Religious belief

ion

uit

Int

Presen

ce o

f re

lati

ves

Accessibility

Medical & Logistic

preparation

Financial

forecast

nce

ura

Self care

Emotional

supports

Ins

Pre

nat

al

ca

re

Management of

complications

rm

No

ien

ce

wife

Mid

Exp

er

Av

oid

an

ce

Psychological readiness

Risk management

Perceived

risk of

homebirth

Decision to birth at

home

Perceived

risk of

hospital birth

Fig. 1. Conceptual model explaining how women manage the risk of home birth.

Table 1

Background characteristics of participating women

at the time of interviews.

Characteristic

Number

Place of previous delivery

Home

Hospital

Without previous experience

7

7

7

Midwife

Educated midwife

Trained midwife

Traditional birth attendance

9

8

4

Type of delivery

Normal delivery

Caesarean section

Without previous delivery

Parity

First child

Second child

Third or more

Insurance

With insurance

Without insurance

11

3

7

Some of my neighbours and relatives said that the hospital has

lots of risks. (Interviewee 14, age 29 years).

As a result, the care provided in hospitals may be considered

risky and unacceptable in the sociocultural context of Zahedan. In

line with what the women had heard, learned and experienced

during their lives, they decided not to go to hospital, particularly

for their rst childbirth, as they believed that they would be hurt,

get sick and experience bleeding (e.g. abnormal bleeding after

childbirth).

The women had negative attitudes towards caesarean section,

which is performed in hospital. A number of women declared

their general feelings about caesarean sections through the

following narratives:

Caesarean is an awful misery. (Interviewee 5, age 39 years).

Caesarean is an adversity. (Interviewee 2, age 32 years).

7

5

9

10

11

hospital birth. One woman recalled her experience of hospital

birth:

When I was stitched up after my rst childbirth, I had pain, it

became infected, I had too many problems. So, I refused to go to the

hospital for my second childbirth. (Interviewee 17, age 38 years).

This view was derived from personal experience and the

experience of others. For example, with reference to the experience of one of her relatives (her niece), one woman declared:

When her abdomen was opened (the caesarean incision), my

sister said: they were brushing her [wound debridement].

(Interviewee 3, age 35 years).

In addition, caesarean section was considered a threat to their

fertility. One of the women remarked:

I did not want to undergo caesarean because I would like to

have two to three more children, then will have to undergo a

caesarean for all of them. (Interviewee 3, age 35 years).

The women believed that caesarean section ruins the routine

of life. For example, one woman commented:

Perceptions of sociocultural risks

Women learn about the risks of hospital birth from other

people. One woman commented:

Caesarean is an adversity and you need to be hospitalised for

some days. Moreover, after caesarean, I cant take care of my

child and myself. (Interviewee 5, age 39 years).

48

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

Most of the women had an issue with the rationale behind

caesarean section and its wide prevalence in Iran (40% of all

deliveries were by caesarean section in 2009) (Vedadhir et al.,

in press). Baloch women declared that doctors exposed them to

caesarean section unnecessarily in order to achieve quick delivery. One woman expressed her distrust in doctors through the

following statement:

In hospitals, doctors are ready for caesarean, and if the childbirth lasts only for a short time, for some reasons they will

soon precede to an operation. (Interviewee 1, age 37 years).

As a result, these women avoided this risky environment

(hospital) by giving birth at home. They rationalised their attitudes and decisions to give birth at home based on the potential

risks hospital. For example:

Risk management

The following two categories address the management of the

risks of home birth: mental preparation (psychological readiness),

and medical and logistical preparation.

Psychological readiness

Sociocultural, economic, and spiritual contexts increased the

womens mental readiness for decision-making about home birth.

In line with their statements, the current study determined

that mental or psychological preparation is the main category in

rationalising and accepting home birth. The subcategories of

psychological readiness, and medical and logistical preparation

are shown in Fig. 1.

It is better to stay at home and give birth at home because,

considering health and safety, home is much better. (Interviewee 21, age 26 years).

Norms. The data revealed that most women considered home birth

to be safe as it is the socio-cultural norm in their community. As one

of the women noted:

For Baloch women, risks are not merely medical, but are also

shaped and perceived based on sociocultural structures. In perceiving or constructing the risks of childbirth, the women accentuated the notions of gender and gender-based differences,

amongst other structural factors, in the intensively gendered

society of Iran. A 28-year-old woman addressed the issue in this

way:

Our ancestors didnt go to hospitals, my mother, and my

grandmother delivered their babies at home. (Interviewee 7,

age 25 years).

Men think that hospitals are safer; they just know that blood

pressure might be low or high, they just know these things.

They do not enter the delivery room and they do not see what

happens there. (Interviewee 15, age 28 years).

From the viewpoint of Baloch women, threats to their beliefs,

schemas, values and dignity are sometimes considered as greater

dangers than medical risks. Several women shared the following

opinion:

The educated midwives and doctors are quarrelling when you

are complaining of pain and there is no one to help you.

(Interviewee 8, age 24 years).

Many women also addressed the issue of Hijab and their

related concerns in the hospital, asserting its meaning for Muslim

Baloch women. A number of women declared their general

concerns about Hijab as follows:

When we go there, they undress us and we are scared without

Hijab. (Interviewee 7, age 25 years).

They further expressed their feelings toward hospitals through

declarations such as:

I am afraid of hospitals, I have stress, and the name of hospital

itself is horrible. (Interviewee 1, age 37 years).

While the data reveal that medical risks are central to

womens health status and should be considered, they also

explain other dimensions of the risks of hospital birth, as

womens signicant beliefs, schemas, values and dignity were

questioned in the hospital. As a nal point, the women always

perceived and rationalised the risks of hospital birth by comparing them with the risks of home birth:

It was my rst childbirth, I had fear, I was afraid of hospitals

more than the risks of home birth. (Interviewee 4, age 21 years).

I wished to have a comfortable and secure childbirth. Therefore, I preferred to stay at home as I found home safer than the

hospital. (Interviewee 9, age 19 years).

Previous personal or family experience. The women considered

home to be an appropriate place for natural childbirth, and

relied heavily on their mothers positive experiences:

Our mothers have given birth at home and they have good

ideas about homes. (Interviewee 6, age 19 years).

Of all our relatives, no one goes to hospitals, all give birth at

home and they have not had a problem. (Interviewee 8, age

24 years).

I said like the others, I will probably not face a problem, God

willing (Enshaallah). (Interviewee 13, age 23 years).

Womens personal positive experiences of home birth justied

and rationalised the safety of home birth and the appropriateness

of their decision. As a result of their constructive lived experience,

Baloch women continually attempted to give birth at home.

As one of the women stated:

Someone says to me if you give birth to your child at home,

you may have bleeding, but I did not have bleeding with my

rst child. (Interviewee 7, age 25 years).

Intuition and avoidance. However, the women did not deny the

risks of home birth. One woman explained the issue in the

following words:

I dont deny all risks as maybe something happens during the

childbirth at home. (Interviewee 18, age 30 years).

In an endeavour to manage the potential risks, or even death,

Baloch women used various mental or psychological coping

mechanisms, including avoidance. The evidence demonstrated

that this avoidance was constructed based on positive experiences, condence in their own and their infants health through

prenatal care, and trust in their intuition. Two women expressed

their sense of condence as follows:

I didnt think about the end and what will happen. I just

thought about the beginning. (Interviewee 21, age 26 years).

When I was completely aware that my child is healthy and I

knew that childbirth at home is comfortable, I didnt think that

something might suddenly happen to my child. (Interviewee 3,

age 35 years).

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

Religious belief. Moreover, facing the potential risks, they resorted

to God. They experienced relaxation and peace by accepting the

divine providence, and believing that the risks are independent of

the place of childbirth. A number of women declared their faith

in God:

I entrust myself to God, while in danger. (Interviewee 8, age

24 years)

Death and life of a human is in the hands of God, if God wants

you to die, you will die, no matter where you are, here or in

hospital. (Interviewee 15, age 28 years).

Based on the above-mentioned beliefs, for Baloch women,

childbirth at home is advantageous and offers comfort. Hence,

they avoided an escapable risk and accepted their destiny in some

way (unavoidable risk). As one women noted:

All risks and difculties of childbirth are not predictable from

the beginning. We said its in Gods hand and we got rid of

hospitals. (Interviewee 4, age 21 years).

Medical preparation

Prenatal care to ensure a healthy pregnancy and childbirth. One of

the most important issues addressed by the women in this study

was that home is the place for childbirth for women without

problems:

That is completely correct that hospitals have all the facilities

and equipment but while I dont have any problems and the

child is safe and sound, home is a much better place for

childbirth. (Interviewee 3, age 35 years).

Therefore, they attempted to maintain their own health and

that of their foetus during pregnancy. One woman expressed her

view as follows:

After being sure about health status of the mother and

the baby, the rest is in the hands of God. (Interviewee 4, age

21 years).

Women had health cheques including sonography, routine

laboratory tests and physical examinations during pregnancy. In

this way, they ensured their own health prior to giving birth at

home. As one woman commented:

I was sure that no problems would occur as the doctor had told

me that the child was ok and the childbirth is normal.

(Interviewee 3, age 35 years).

However, if any medical or clinical problems were diagnosed,

the women acted to protect and improve their health in order to

give birth at home:

If they say that the blood pressure is high, well be more

careful. (Interviewee 8, age 24 years).

The lady said that your blood pressure is high; I visited a

doctor two or three times, the doctor prescribed me half a high

blood pressure tablet per day and I took them so I was told

I didnt have the problem anymore. (Interviewee 14, age 29

years).

These women were determined to give birth to their children

at home, partly because they had not been referred to hospital by

a doctor. As one woman declared:

The personnel and the doctor of the health-care centre told me

your anaemia isnt serious. (Interviewee 13, age 23 years).

49

A key point that can endanger the health of mothers and

infants is the belief among women that a healthy pregnancy

guarantees safe childbirth and the health of the infant:

If you are being checked and supervised during these nine

months and you have no problems, it is unlikely to face a

problem such as fetal hazards during delivery. (Interviewee 3,

age 35 years).

Trust in midwife. Some evidence suggested that the role of the

midwife was important in decision-making about giving birth at

home:

I thought about childbirth risks, I did believe that the equipment of hospital is more, even so I asked the idea of my

midwife. She said that childbirth at home doesnt have any

risks and you can easily give birth to your child at home.

(Interviewee 9, age 19 years).

I was completely sure about my grandmothers job (uneducated local midwife) and that nothing would happen. (Interviewee 10, age 23 years).

The close relationship between the woman and her midwife

prepared women to trust and follow their midwife. As a result,

midwives screening and referrals of complicated cases to the

hospital were highly signicant. Moreover, women abdicated the

active role of checking their health during pregnancy to the

midwife, an important issue for maternal mortality. They trusted

and relied on their midwife to diagnose and manage the potential

risks. As one woman stated:

My mother told me that you will bleed, I said: if I bleed, my

midwife will diagnose. My midwife is educated; if a problem

occurs she will take me to the hospital. (Interviewee 1, age

37 years).

Delayed diagnosis of a problem can lead to a mothers death.

One woman stated:

If the midwife says theres a problem and the child is not going

to be born here, then we will take her to hospital; whatever

the midwife says I will accept. (Interviewee 7, age 25 years).

Although the women believed that hospitals are risky places

that should be avoided for the health of their infant and

themselves, they acknowledged its protective role. As one woman

noted:

Hospitals have oxygen and instruments for taking blood

pressure, these are good. (Interviewee 16, age 23 years).

However, hospital visits only occurred when all endeavours to

give birth at home failed and the woman was forced to go to

hospital. One woman said:

If the midwife comes and diagnoses a difcult childbirth and it

is really impossible to give birth to the child at home, then we

will have to go to the hospital. (Interviewee 8, age 24 years).

Sometimes, these compulsions were also related to the diagnosis of fetal compromise during pregnancy and childbirth. One

women said:

If the doctor tells you the suffocation of the fetus is probable,

we will go to the hospital. For instance, for my rst childbirth,

they told me that the child has passed stool (meconium) and

would suffocate. Well, in such cases we are ready even for

caesarean. (Interviewee 8, age 24 years).

50

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

The role of relatives. From the start of decision-making to the end

of childbirth, the role of the husband in supporting and

actualising the decision to give birth at home, or preventing the

woman from giving birth at home was quite important. In fact,

the mens high perception of medical risks led the women

towards hospitals. One woman explained:

My husband was saying that he wouldnt let me have childbirth at home. He told me that I am afraid you have already

undergone caesarean. (Interviewee 2, age 32 years).

In addition, the womens perception or construction of the

risks was important. When women perceived their home to be

safer than hospital and decided to give birth at home, they used

various methods to remove resistance to their decision. Having

the support of their husband was an essential aspect of giving

birth at home. The following quotations reect how husbands in

the Baloch community play a key role in rationalising and

decision-making about the mode of childbirth:

My husband wanted me to go to hospital. I explained the

problems of hospitals to him and convinced him that home is

better for me and Im more comfortable at home. (Interviewee

3, age 35 years).

At last, the husbands family and even more important than

them, the husband, should agree with childbirth at home.

(Interviewee 9, age 19 years).

Furthermore, home birth was associated with tranquillity and

condence:

I feel relaxed when everyone is beside me, my mother, my

father, my husband, my uncles, my mother-in-law; they are all

there. (Interviewee 10, age 23 years).

If something happens, my family and relatives are present to

take me to hospital. (Interviewee 3, age 35 years).

Financial forecast. The womens narratives indicated that nancial

forecast was occasionally provided by insurance:

I forecast to have childbirth at home; I said I would get my

insurance so that if a problem occurred, I would not face any

problem to pay the money. (Interviewee 17, age 38 years).

I get insurance for a rainy day, I said maybe I should go to the

hospital. (Interviewee 14, age 29 years).

As a nal point, Baloch women described their home births

with satisfaction:

I am absolutely pleased with my childbirth at home. (Interviewee 6, age 19 years).

Discussion

This study investigated how childbirth decisions are made by

Baloch women, and how they rationalise and justify their decisions to give birth at home. More specically, this qualitative

study explored Baloch womens constructions and lived

experiences of childbirth in order to develop an understanding

of how they perceive, typify and manage the risks of home birth

in comparison with the risks of hospital birth. This article

primarily calls attention to the point that childbirth does not

occur in a sociocultural vacuum, but is a sociocultural construction (Ishikawa et al., 2002). According to Selin and Stone (2009,

p. xvi), decisions about childbirth regarding place of birth,

position, who receives the baby and even how the mother may

or may not behave during the actual delivery, are usually made by

other people. This study revealed that Baloch women living in

Zahedan continue to choose to give birth at home, despite the

availability of specialised childbirth services.

The homebirth decision-making process involves assessment

of the risks and benets of giving birth at home and in hospital.

As Gutnik et al. (2006) discussed, one of prevailing systems that

people use to realise and assess risk is experimental system.

This system uses past or lived experiences, emotion-related

association and intuition when making decisions. People often

assess a risk associated with a behaviour or lifestyle in terms of

how easily they can recollect past examples, or how easily they

can picture such episodes. In contrast, diseases or harmful

conditions that are difcult to imagine (because of unfamiliarity)

may reduce the perceived likelihood that they will occur

(Timmermans, 2005). By telling birth stories or narratives,

women teach other women about risk. Hence, knowledge and

mythology of childbirth and its risk is constructed and legitimised

through social interaction among women (Nolan, 2011, p. 25).

For the women in the current study, personal experience and

knowing people, including close relatives, who had experienced

negative technical and ethical aspects of hospital care affected

their view of the risks associated with hospital birth.

The medical and risk-averse approach, which indicates the

need for hospitalisation and medical care of all women (Jomeen,

2010, p. 15), has neglected many important forms of care that

make women feel safe, such as psychological and social impacts

(El-Nemer et al., 2006; Catling-Paull et al., 2010). Some women

doubt the quality of clinical care in hospital and, at times, even

perceive it to be risky (Tinoco-Ojanguren et al., 2008). Some of the

practices employed in hospital are not acceptable to women, and

are considered a threat to their safety and fertility. In addition, the

multiparous women in the current study stressed unethical or

immoral aspects of hospital care. Consequently, these negative

experiences of hospital care led to a sense of fear and dread.

Sjoberg (2004) asserted the risk-as-feeling hypothesis that

responses to risky situations result, in part, from the inuence

of direct emotions, including feelings such as worry, fear, dread,

or anxiety. Negative emotions related to these experiences

inuence individuals habitus, schemas, attitudes, images, judgements (Gutnik et al., 2006), and perceived risk (Sjoberg, 2000).

This can lead to exit (switching to other products/services or

suppliers) and negative word of mouth about services (East et al.,

2008, p. 168). Evidence showed that services are likely to be more

responsive to word of mouth than most goods. Furthermore,

those who complained about health services were over four times

more likely to defect than those who did not (East et al., 2008,

p. 184). Dahlen (2010) discussed the 0.1% doctrine in maternity

care, and explained that we think about the one adverse event

rather than the entire positive outcome. However, women in this

study moved from the 0.1% to 99.9% doctrine, meaning that they

concentrated on all the positive outcomes more than the one

adverse event. The results of this study are consistent with similar

ndings that people engage with risk deliberately because they

are looking for particular benets linked to that particular risk,

rather than taking risks without the awareness that they are

doing so (Soane and Chmiel, 2005).

There is ample evidence that when women decide to give birth

at home, they consider the risks of this mode of childbirth

(Catling-Paull et al., 2010; Lindgren et al., 2010; Nolan, 2011,

p. 29). Accordingly, these women must be prepared psychologically. Risk is closely tied to cultural adherence and social learning,

as argued by proponents of the cultural theory. Depending on

whether one is socially participating and which groups one

belongs to, one will focus on different types of risk. People choose

what to fear and how much to fear it (Oltedal et al., 2004). As the

ndings revealed, home birth is common among Iranian Baloch

families, and the womens stories and lived experiences support

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

its safety. As a result, they characterised and constructed this

mode of childbirth with low risks. Culture is based on the

uniquely human capacity to classify experiences, encode such

classication symbolically, and teach such abstractions to others.

It is acquired through enculturation, the process through which

an older generation induces and compels a younger generation to

reproduce the establish lifestyle (Oltedal et al., 2004). Therefore,

the interviewed women relied on their relatives experiences and

followed their ways of life. From this view, home birth could be

interpreted as a manifestation of faithlessness or distrust in

science and the authority of the medical profession (Mitchell,

2010).

People consider natural burden and risks as prescribed, almost

inevitable, destiny while technical risks are considered to be

consequences of decisions and actions. If none other than God

can be held accountable, no amount of human activity will

improve the situation. The only alternatives are either to ee

from risky situations or to deny their existence. People are more

likely to deny or suppress rare events. For common events, people

are more likely to ee from the danger zone (Renn, 2004). In this

situation, women can nd peace in reading the Holy Quran,

praying and requesting Gods protection from potential risks.

Another type of decision-coping style addressed in the present

study is defensive avoidance. This style involves techniques such

as procrastination to avoid or postpone conict. Under defensive

avoidance, the decision-maker seeks to avoid any cues that could

potentially increase his/her anxiety. This is a maladaptive coping

style, as it is characterised by a biased and incomplete evaluation

of information and often does not result in an optimal outcome

(Creyer and Kozup, 2003). As Creyer and Kozup (2003) explained,

if women do not assure their physical well-being and have logistic

necessities, such as giving birth in the presence of an educated

midwife, they are at increased risk for maternal mortality and

morbidity. As a result, people who have a tendency to rely solely

on defensive avoidance and fate need assistance from individuals

who tend not to be defensive avoidant.

Condence is described as an ability to cope with risks and

insecurity. Condence consists of condence in oneself, condence in other people, and condence in organisations or systems

(Lindgren et al., 2006). The data demonstrated womens faith in

their ability to give birth at home and their intuitive knowledge/

feeling that no harm would occur (Viisainen, 2001; Sjoblom et al.,

2006; Lindgren et al., 2010). Womens faith in their own intuition

is hence a crucial motivating factor in their decision to give birth

at home.

Women with psychological preparation or readiness need

support to perform their decision. The data show that all Baloch

women regularly attended antenatal care appointments with the

public and private health-care systems. They considered this to be

an integral part of preparation for home birth. If an infant dies at

home, it is immediately presumed that negligence and/or irresponsibility on the part of the mother must be a signicant factor

(Nolan, 2011, p. 25). As Viisainen (2001) discussed, medical

check-ups and management of medical complications, such as

treatment of high blood pressure, could provide reassurance that

the pregnancy was medically safe, and this made the women feel

physically powerful and condent to have a normal birth at home.

In this way, they can defend their choice and receive positive

afrmation from relatives and health workers.

At the same time, women receive professional support through

the presence of midwives. As Jordan and Murphy (2009) noted,

women rely on midwives to determine their risk status and

provide measures to reduce the risk. As Morison et al.s study

(1999) revealed, based on a sense of trust within the relationship,

women accept midwives as individuals who decide when medical

assistance and hospital transfer is required. As a result of the

51

support they received from midwives and relatives, women were

able to escape the vicious cycle in which risk labelling traps

women, according to Nolan (2011, p. 32). The midwives helped

women to develop condence in their own decision, ability to

give birth and preparation for unpredictable complications.

Although the women embraced home birth in an endeavour to

reduce the likelihood of having a caesarean section, and to

achieve normal childbirth in a safe and secure environment, they

relied on hospital resources and expertise when they perceived

risk. The results of this study are consistent with MacKenzie

Bryers and Van Teijlingen (2010), who stated that a more holistic

approach to maternity services is required. This indicates that

although science and technology have a place, they should be

used to support social and cultural structures and the preferences

of the women. In the eld, this is interpreted as home birth or

low-technique childbirth facilities within local communities with

back-up from comprehensive emergency obstetric care units for

probable complications.

Conclusion

The ndings of this qualitative study are signicant in that the

home is not simply a place to live with family, but also serves as a

shelter. It is a safe and amenable place for childbirth that protects

woman from the risks of hospital birth, including the risks of

caesarean section and other interventions, in the context of a

fairly medicalised society. In addition, being at home protects

women from the immorality perspective of hospital care, which is

sometimes a more important risk than the technical aspects of

hospital care. The ndings also showed that women who

expressed an anti-hospital view and chose to give birth at home

accepted the potential complications. However, they attributed

these complications to fate, unlike hospital complications related

to interventions. When women give birth at home after full

preparation, dimensional support and in the presence of a

qualied or educated midwife, documents have shown that

maternal mortality is lower than that for hospital birth

(Ministry of Health and Medical Education, 1996). Maternal

mortality data and research observations have also shown that

most maternal mortality in Iran is associated with women who

use defensive avoidance, rely on past experiences, and are

attended by traditional birth attendants and relatives (Ministry

of Health and Medical Education, 1996).

The limitations of the current study include the fairly small

group of women recruited from Zahedan in southeast Iran, and

the voluntary nature of participation. All interviewed women

were Baloch in terms of ethnicity and Sunni Muslim in terms of

religion. Therefore, the cultural, ethnic and religious contexts of

the participants were not deeply explored. The study may reect

a unique situation within the main city of the province; therefore,

no claims are made regarding the wider generalisability of

ndings, considering that the cities in Sistan and Balochestan

province are highly heterogeneous in terms of socio-economic,

demographic and ethnoreligious criteria. Further studies are

needed to explore the issues raised. It is expected that the audit

trail assists to establish trustworthiness, creditability and transferability of the ndings and the key implications developed.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the study ndings offer valuable insight into the lived experiences and socioculturally constructed reality of childbirth and modes of childbirth among

Iranian Baloch women. Given the limited body of evidence and

information concerning childbirth in Iran, the ndings of this

study may be valuable to other researchers in light of the recent

endeavours to explore the process of childbirth through globally

and culturally diverse perspectives, namely childbirth across

52

Z. Abed Saeedi et al. / Midwifery 29 (2013) 4452

cultures (Selin and Stone, 2009). Finally, the multi- and transdisciplinary approach used in this study seems to offer a valuable

contribution to understanding the process of decision-making

and potential ambivalences that surround the rationalisation and

choice of mode of childbirth in communities with a traditional

and religious perspective. Furthermore, this study provides some

evidence to suggest that future scholars should be encouraged to

consider qualitative enquiry in understanding decision-making

and the ways of knowing about and managing the risks of home

birth.

References

Bassett, C., 2004. Qualitative Research in Health Care. Whurr Publisher Ltd.London.

Berry, N.S., 2006. Kaqchikel midwives, homebirth, and emergency obstetric

referral in Guatemala: contextualizing the choice to stay at home. Social

Science and Medicine 62, 19581969.

Bourdieu, P., 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

Catling-Paull, C., Dahlen, H., Homer, C.C.S.E., 2010. Multiparous womens condence to have a publicly-funded homebirth: a qualitative study. Women and

Birth 24, 122128.

Chan, Z.C.Y., 2009. Psychology of decision-making: 6Rs for qualitative research

methodological development. In: Murphy, D., Longo, D. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of

Psychology of Decision Making. , Nova Science Publishers, New York.

Cockerham, W.C., 2007. Social Causes of Health and Disease. Polity Press,

Cambridge.

Creyer, E.H., Kozup, J.C., 2003. An examination of the relationships between coping

styles, task-related affect, and the desire for decision assistance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 90, 3749.

Dahlen, H., 2010. Undone by fears? Deluded by trust? Midwifery 26, 156162

Donnay, F., 2000. Maternal survival in developing countries: what has been done,

what can be achieved in the next decade? International Journal of Gynecology

and Obstetrics 70, 8997.

Duong, D.V., Binns, C.W., Lee, A.H., 2004. Utilization of delivery services at the

primary health care level in rural Vietnam. Social Science and Medicine

59, 25852595.

East, R., Wright, M., Vanhuele, V., 2008. Consumer Behaviour. Sage, London.

El-Nemer, A., Downe, S., Small, N., 2006. She would help me from the heart: an

ethnography of Egyptian women in labour. Social Science and Medicine

62, 8192.

Gabrysch, S., Campbell, O.M., 2009. Still too far to walk: literature review of the

determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9:34 /http://

www.biomedcentral.com/14712393/9/34/S (last accessed July 2011).

Gibbs, G., 2007. Analyzing Qualitative Data. Sage, Los Angeles, CA.

Gutnik, L.A., Hakimzada, A.F., Yoskowitz, N.A., Patel, V.L., 2006. The role of emotion

in decision-making: a cognitive neuroeconomic approach toward understanding sexual risk behavior. Journal of Biomedical Information 39, 720736.

Holton, J.A., 2007. The coding process and its challenges. In: Bryant, A., Chatmaz, K.

(Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory.Sage, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 265289.

Integrated Management Evaluation System, 1994. Maternal Program Index.

Ministry of Health & Medical Education of Iran. Unpublished data.

Ishikawa, N., Simon, K., Porter, J.D.H., 2002. Factor affecting the choice of delivery

site and incorporation of traditional birth customs in a refugee camp, Thailand.

International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 78, 5557.

Jomeen, J., 2010. Choice, Control and Contemporary Childbirth. Understanding

Through Womens Stories. Radcliffe Publishing, Oxford.

Jordan, R.G., Murphy, P.A., 2009. Risk assessment and risk distortion: nding the

balance. Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health 54, 191200.

Kanti, P.B., Rumsey, D.J., 2002. Utilization of health facilities and trained birth

attendants for childbirth in rural Bangladesh: an empirical study. Social

Science and Medicine 54, 17551765.

Lindgren, H.E., Rsdestad, I.J., Kyllike, C., et al., 2010. Perception of risk and risk

management among 735 women who opted for a home birth. Midwifery

26, 163172.

Lindgren, H., Hildingesson, I., Radestan, I., 2006. A Swedish interview study:

parents assessment of risks in home births. Midwifery 22, 1522.

McGhee, G., Marland, G.R., Atkinson, J., 2007. Grounded theory research: literature

reviewing and reexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing 60, 334341.

MacKenzie Bryers, H., Van Teijlingen, E., 2010. Risk, theory, social and medical

models: a critical analysis of the concept of risk in maternity care. Midwifery

26, 488496.

Malekafzali, H., 2009. Primary health care in the rural area of the Islamic Republic

of Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health 38, 6970.

Maternal Health Ofce, 2011. Maternal Health Index. Zahedan. Unpublished data.

Ministry of Health and Medical Education, 1996. National Maternal Mortality

Surveillance System. Tandis, Iran.

Mitchell, M., 2010. Risk, pregnancy and complementary and alternative medicine.

Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 16, 109113.

Morison, S., Percival, P., Hauck, Y., McMurray, A., 1999. Birthing at home: the

resolution of expectations. Midwifery 15, 3239.

Morse, J.M., 2007. Sampling in grounded theory. In: Bryant, A., Charmaz, K. (Eds.),

The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory. Sage, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 229264.

Murphy, D., Longo, D. (Eds.), 2009. Encyclopedia of Psychology of Decision Making.

Nova Science Publishers, New York.

Nolan, M., 2011. Home Birth: The Politics of Difcult Choices. Routledge, London.

Oltedal, S., Moen, B.E., Klempe, H., Rundmo, T., 2004. Explaining Risk Perception. An

Evaluation of Cultural Theory. C Rotunde publikasjoner, Trondheim. /http://www.

svt.ntnu.no/psy/Torbjorn.Rundmo/Cultural_theory.pdfS (last accessed November

2011).

Pidgeon, N., Henwood, K., 2009. Grounded theory. In: Hardy, M., Hardy, M., Bryman

(Eds.), The Handbook of Data Analysis. Sage, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 625648.

Renn, O., 2004. Perception of risks. Toxicology Letters 149, 405413.

Say, L., Raine, R., 2007. A systematic review of inequalities in the use of maternal

health care in developing countries: examining the scale of the problem and

the importance of context. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85,

812818.

Selin, H., Stone, P.K. (Eds.), 2009. Childbirth Across Cultures: Ideas and Practices of

Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Postpartum. Springer, London.

Sjoberg, L., 2000. Factors in risk perception. Risk Analysis 20, 111.

Sjoberg, L., 2004. Explaining Risk Perception. An Evaluation of the Psychometric

Paradigm in Risk Perception Research. C Rotunde publikasjoner, Trondheim. /

http://paul-hadrien.info/backup/LSE/IS%20490/utile/Sjoberg%20Psychometric_

paradigm.pdfS (last accessed November 2011).

Sjoblom, I., Nordstrom, B., Edberg, A.K., 2006. A qualitative study of womens

experiences of home birth in Sweden. Midwifery 22, 348355.

Soane, E., Chmiel, N., 2005. Are risk preferences consistent? The inuence of

decision domain and personality. Personality and Individual Differences 38,

17811791.

Steinberg, S., 1996. Childbearing research: a transcultural review. Social Science

and Medicine 43, 17651784.

Teddlie, C., Tashakkori, A., 2009. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research. Sage,

Los Angeles, CA.

Timmermans, D.R.M., 2005. Prenatal screening and the communication and

perception of risks. International Congress Series 1279, 234243.

Tinoco-Ojanguren, R., Glantz, N.M., Martinez-Hernandez, I., Ovando-Meza, I., 2008.

Risk screening, emergency care, and lay concepts of complications during

pregnancy in Chiapas, Mexico Social Science and Medicine 66, 10571069.

United Nations Population Fund, 2002. Maternal Mortality Update: A Focus on

Emergency Obstetric Care. UNFPA, New York. /http://www.unfpa.org/upload/

lib_pub_le/201_lename_mmupdate-2002.pdfS (last accessed November

2011).

Vedadhir, A., Hosseinejad, F., Sadati, S.M.H., Taghavi, S. Childbearing as a sociocultural problem: a constructionist approach to the cesarean section in Tabriz,

Iran. Iranian Journal of Anthropological Research 1, in press.

Viisainen, K., 2001. Negotiating control and meaning: home birth as a selfconstructed choice in Finland. Social Science and Medicine 52, 11091121.

World Health Organization, 2010. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2008.

World Health Organization, Geneva. /http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/glo

bal/shared/documents/publications/2010/trends_matmortality90-08.pdfS

(last accessed November 2011).

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- GraduateList2015 PDFDocument34 paginiGraduateList2015 PDFVenky DravidÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCAT - Psych TheoriesDocument44 paginiMCAT - Psych Theoriesjohn blasinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2009 Book MaternalAndChildHealth PDFDocument584 pagini2009 Book MaternalAndChildHealth PDFThierry UhawenimanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study Guide 6 - Transcultural Perspectives in ChildbearingDocument12 paginiStudy Guide 6 - Transcultural Perspectives in ChildbearingTim john louie RancudoÎncă nu există evaluări

- UCSP Module 9Document21 paginiUCSP Module 9Melyjing Milante100% (1)

- Oliver Marchart, Art, Space and The Public SphereDocument19 paginiOliver Marchart, Art, Space and The Public SphereThiago FerreiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument73 pagini09 - Chapter 2 PDFNaveen Kumar100% (1)

- Nurse in The National and Global Health Care Delivery SystemDocument9 paginiNurse in The National and Global Health Care Delivery Systemczeremar chanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Erving GoffmanDocument6 paginiErving GoffmanAlina PodeanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy Medical, Psychosocial, and Public Health ResponsesDocument699 paginiInternational Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy Medical, Psychosocial, and Public Health ResponsesSari Yuli AndariniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Anc Services Among Reproductive Age Group Women at DR Khalid MCH, in 26 June District, Hargeisa-SomalilandDocument29 paginiAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Anc Services Among Reproductive Age Group Women at DR Khalid MCH, in 26 June District, Hargeisa-SomalilandSuleekha CabdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-George Herbert Mead and Human ConductDocument218 pagini1-George Herbert Mead and Human ConductSrªcavalcanti100% (1)

- Language Ideologies: Practice and TheoryDocument21 paginiLanguage Ideologies: Practice and TheorycaroldiasdsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jiva Goswami Sri Bhagavat SandarbhaDocument199 paginiJiva Goswami Sri Bhagavat SandarbhaJSK100% (2)

- Hughes, Thomas P. - The Seamless Technology, Science, Etcetera, EtceteraDocument13 paginiHughes, Thomas P. - The Seamless Technology, Science, Etcetera, Etceterarafaelbennertz100% (1)

- CHN Reportfinalllledited2023 MmmmmvsvlatestDocument19 paginiCHN Reportfinalllledited2023 MmmmmvsvlatestShahbaz aliÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Holistic Approach To Population Control in IndiaDocument3 paginiA Holistic Approach To Population Control in IndiaOscar Alejandro Cardenas QuinteroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quality of Life of Women With InfertilityDocument9 paginiQuality of Life of Women With InfertilityIshrat PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter One Background To The StudyDocument102 paginiChapter One Background To The StudythesaintsintserviceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Project GodwinDocument51 paginiResearch Project GodwinBless UgbongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excerpts From An Unpublished Thesis: WWW - Usaid.govDocument4 paginiExcerpts From An Unpublished Thesis: WWW - Usaid.govJaylen CayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal: University of Port Harcourt of Nigeria Association For Phys Ical, HealthDocument14 paginiJournal: University of Port Harcourt of Nigeria Association For Phys Ical, Healthlivesource technologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Mortality PDFDocument101 paginiMaternal Mortality PDFCamille Joy BaliliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Brought at A Tender Age: The Lived Experiences of Filipino Teenage Pregnant WomenDocument5 paginiLife Brought at A Tender Age: The Lived Experiences of Filipino Teenage Pregnant WomenAsia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary ResearchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ebook PDF Childbirth Vulnerability and Law Exploring Issues of Violence and Control PDFDocument41 paginiEbook PDF Childbirth Vulnerability and Law Exploring Issues of Violence and Control PDFmike.casteel807100% (35)

- Countdown To 2015 - Maternal Newborn and Child SurvivalDocument228 paginiCountdown To 2015 - Maternal Newborn and Child SurvivalNewborn2013Încă nu există evaluări

- Life Brought at A Tender Age: The Lived Experiences of Filipino Teenage Pregnant WomenDocument5 paginiLife Brought at A Tender Age: The Lived Experiences of Filipino Teenage Pregnant WomenRolando E. CaserÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproductive Health Policy Saga: Restrictive Abortion Laws in Low-And Middle-Income Countries (Lmics), Unnecessary Cause of Maternal MortalityDocument20 paginiReproductive Health Policy Saga: Restrictive Abortion Laws in Low-And Middle-Income Countries (Lmics), Unnecessary Cause of Maternal Mortality7 MNTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Childbirth in Cross-Cultural PerspectiveDocument16 paginiChildbirth in Cross-Cultural PerspectivemoehammadjÎncă nu există evaluări

- FulltextDocument19 paginiFulltextibrahimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper Reproductive HealthDocument11 paginiResearch Paper Reproductive Healthapi-613297004Încă nu există evaluări

- Abortion Report WritingDocument17 paginiAbortion Report WritingShahbaz aliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abortion in Burkina FasoDocument7 paginiAbortion in Burkina FasosimonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abortion Among Adolescents and Youth Is A Major Public Health IssueDocument9 paginiAbortion Among Adolescents and Youth Is A Major Public Health IssueJUVY ANN RETUYAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mistreatment of Women During, Bohren 2015Document32 paginiThe Mistreatment of Women During, Bohren 2015Umratun Sirajuddin AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20604-Article Text-65316-2-10-20180726 PDFDocument8 pagini20604-Article Text-65316-2-10-20180726 PDFMALIK MANASRAHÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Breast Is BestDocument23 paginiFrom Breast Is BestTreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abortion Position PaperDocument3 paginiAbortion Position PaperCloyd john DaligdigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Background of The StudyDocument16 paginiBackground of The StudyIvan Matthew SuperioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transcultural ChildbearingDocument11 paginiTranscultural ChildbearingVerysa MaurentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproductive Health and Women Constructive Workers: Ruhi GuptaDocument4 paginiReproductive Health and Women Constructive Workers: Ruhi GuptainventionjournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Health Education Intervention On Knowledge of Safe Motherhood Among Women of Reproductive Age in Eleme, Rivers State, NigeriaDocument13 paginiImpact of Health Education Intervention On Knowledge of Safe Motherhood Among Women of Reproductive Age in Eleme, Rivers State, Nigerialivesource technologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Sexual and Reproductive Health Promotion What Are Sexual Health Issues How Sexual and Reproductive Health Status Can Be ImprovedDocument4 paginiWhat Is Sexual and Reproductive Health Promotion What Are Sexual Health Issues How Sexual and Reproductive Health Status Can Be ImprovedIJARP PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Six Steps Towards Ending Preventable Maternal MortalityDocument8 paginiSix Steps Towards Ending Preventable Maternal MortalityThe Wilson Center100% (1)

- Literature Review On Maternal DeathsDocument7 paginiLiterature Review On Maternal Deathsea7e9pm9100% (1)

- Sexual and Reproductive HealthDocument6 paginiSexual and Reproductive HealthYSÎncă nu există evaluări

- NAVITHEARTISTDocument57 paginiNAVITHEARTISTADHITHIYA VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abortion and Womens Health - April 2017Document28 paginiAbortion and Womens Health - April 2017Gabriel SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review On StillbirthDocument6 paginiLiterature Review On Stillbirthaflsvagfb100% (1)

- MenarcheDocument24 paginiMenarcheTaskeen MansoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Access To Childbirth CareDocument67 paginiAccess To Childbirth CareemeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Does Halakhah Consider Female Infertilit PDFDocument14 paginiDoes Halakhah Consider Female Infertilit PDFNino MdinaradzeÎncă nu există evaluări

- ID NoneDocument12 paginiID NoneRuby HendrawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociodemographic Determinants of Pregnancy Outcome: A Hospital Based StudyDocument5 paginiSociodemographic Determinants of Pregnancy Outcome: A Hospital Based StudysagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Encouraging The Provision of Considerate Respectful Maternity Care On A Global Scale-An Essential Human RightDocument7 paginiEncouraging The Provision of Considerate Respectful Maternity Care On A Global Scale-An Essential Human RightIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal ThesisDocument10 paginiMaternal ThesisMerwynmae PobletinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bìa Research WritingDocument10 paginiBìa Research WritingHạ Tịch PhươngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abortion ResearchDocument56 paginiAbortion Researchcodmluna3Încă nu există evaluări

- Conceptulising StigmaDocument16 paginiConceptulising StigmaRitesh kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- RH AwarenessDocument23 paginiRH AwarenessAthena ChoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- GyniDocument41 paginiGynitesfaye gurmesaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brunke T n332 EthicalpaperDocument13 paginiBrunke T n332 Ethicalpaperapi-260168909Încă nu există evaluări

- Asylum SeekersDocument25 paginiAsylum SeekersMark KrepflÎncă nu există evaluări

- JURNAL International Journal of Humanities and Social Science InventionDocument15 paginiJURNAL International Journal of Humanities and Social Science InventionyarmimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-6 Amos Catherine UlummaAmosDocument83 pagini1-6 Amos Catherine UlummaAmosmrpboss1Încă nu există evaluări

- Big Shara Ayu Permata Sari P27824319028Document2 paginiBig Shara Ayu Permata Sari P27824319028sintaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women Autonomy and Maternal Healthcare Services Utilization Among Young Ever-Married Women in NigeriaDocument12 paginiWomen Autonomy and Maternal Healthcare Services Utilization Among Young Ever-Married Women in NigeriaPi PoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genetics Published ArticleDocument5 paginiGenetics Published ArticleNumayrÎncă nu există evaluări

- jcpp2613 PDFDocument22 paginijcpp2613 PDFJorge Fernández BaluarteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mediterranean: Third TextDocument12 paginiThe Mediterranean: Third TextbegomyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monique Nuijten Power in Practice A Force Field ApproachDocument14 paginiMonique Nuijten Power in Practice A Force Field ApproachGabrielaAcostaEspinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Psychology - Kassin Chapters 1 and 2Document6 paginiSocial Psychology - Kassin Chapters 1 and 2Suzie NavajoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Name of Learner: - Gr/Section - Teacher: Ma. Victoria L. Valenzuela, LPT - DateDocument3 paginiName of Learner: - Gr/Section - Teacher: Ma. Victoria L. Valenzuela, LPT - DateMa Victoria Lopez VaLenzuelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Epistemology PDFDocument13 paginiSocial Epistemology PDFPete Moscoso-FloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basso-To Give Up On WordsDocument19 paginiBasso-To Give Up On WordsŞtefan PintÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethnographic Content Analysis PDFDocument2 paginiEthnographic Content Analysis PDFDrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Betinho DiesDocument1 paginăBetinho Diestecacruz100% (2)

- Jurisprudence ProjectDocument16 paginiJurisprudence ProjectCHANDRIKAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bulanadi Chapter 1 To 3Document33 paginiBulanadi Chapter 1 To 3Anonymous yElhvOhPnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Studying Social Problems in The Twenty-First CenturyDocument22 paginiStudying Social Problems in The Twenty-First CenturybobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sefa SimsekDocument29 paginiSefa SimsekDiyavolPasaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociology StandardsDocument2 paginiSociology StandardsRingle JobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interaction Through LanguageDocument195 paginiInteraction Through LanguageVick'y A'AdemiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supervision As Moral Action: Ronald M. Suplido JRDocument59 paginiSupervision As Moral Action: Ronald M. Suplido JRJocel D. MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Background of Indian Naational by Ar DesaiDocument399 paginiSocial Background of Indian Naational by Ar DesaiShashank ChandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- IntroductionDocument5 paginiIntroductionSankalp RajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power and InteractionDocument18 paginiPower and Interaction吴善统Încă nu există evaluări

- Exploring Disability A Sociological IntroductionDocument3 paginiExploring Disability A Sociological IntroductionTengiz VerulavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hermeneutika Emilio BettiDocument6 paginiHermeneutika Emilio BettiIskandar ZulkarnainÎncă nu există evaluări