Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Parents

Încărcat de

ana100%(3)100% au considerat acest document util (3 voturi)

440 vizualizări6 paginiThis document discusses the developmental tasks and roles of new parents. It covers Mercer's and Rubin's theories of parenting as well as the needs of expectant mothers. It then focuses on the roles of mothering and fathering. For fathers, it describes the "Five Ps" of fathering roles: Participator, Playmate, Principled Guide, Provider, and Preparer. Under each role, it provides details on how fathers can fulfill that role and the benefits to children. It emphasizes the importance of fathers being actively involved in multiple aspects of parenting.

Descriere originală:

N elective

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThis document discusses the developmental tasks and roles of new parents. It covers Mercer's and Rubin's theories of parenting as well as the needs of expectant mothers. It then focuses on the roles of mothering and fathering. For fathers, it describes the "Five Ps" of fathering roles: Participator, Playmate, Principled Guide, Provider, and Preparer. Under each role, it provides details on how fathers can fulfill that role and the benefits to children. It emphasizes the importance of fathers being actively involved in multiple aspects of parenting.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

100%(3)100% au considerat acest document util (3 voturi)

440 vizualizări6 paginiThe Parents

Încărcat de

anaThis document discusses the developmental tasks and roles of new parents. It covers Mercer's and Rubin's theories of parenting as well as the needs of expectant mothers. It then focuses on the roles of mothering and fathering. For fathers, it describes the "Five Ps" of fathering roles: Participator, Playmate, Principled Guide, Provider, and Preparer. Under each role, it provides details on how fathers can fulfill that role and the benefits to children. It emphasizes the importance of fathers being actively involved in multiple aspects of parenting.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 6

THE PARENTS

A. Developmental Tasks of Parents to Be:

Mothering and Fathering

B. Mercers Theory and Rubins Theory

C. Behavior and needs of expectant

mothers

D. Mothering Role

E. Fathering Role

F. . Selected situational crises affecting

parental assumption of their role:

1. single parenthood

2. birth of handicapped child

3. adopting a child

4. separation/divorce/annulment

5. hospitalization/death of a

spouse

6. working mother/absentee

parent(s)

A. Developmental tasks of parents to

be: Mothering & Fathering

Duvalls EIGHT-STAGE FAMILY LIFE CYCLE AND

DEVELOPMENTAL TASKS

Developmental Tasks of New Parents

1. Reconciling conflicting conceptions of roles

Clarifying role (wife, mother, person,

husband, father, person)

Coming to terms with ones expectations of

self, spouse, and child.

2. Accepting and adjusting to the strains and

pressures of young motherhood/fatherhood

balancing the demands.

3. Learning how to care for their infant.

Learning skills of feeding

Bathing

Decisions surrounding new child

4. Establishing and maintaining healthy

routines for the family.

Adjusting personal routines to include the

new baby

Adjusting routines to fit with other family

members routines

5. Providing full opportunities fro the childs

development

Enriching the physical situation

Providing many experiences for child to

explore/learn

Child proof house

Accepting child as an individual

6. Sharing the responsibilities of parenthood.

7. Maintaining a satisfying relationship with

spouse.

8. Making satisfactory adjustments to the

practical realities of life

Making decisions about job, day-care, etc

Adapting if necessary to limited financial

resources, social life, friends, etc

9. Maintaining a sense of personal autonomy

10. Exploring and developing the satisfactory

sense of being a family.

Family recreation, joint activities

New associations with other relatives in

their roles as Aunt, Uncles, etc

Fathering Role. Fathers play many roles in

parenting their children. Some are involved

in every facet of their child's life while others

concentrate on one or two aspects of raising

their child

Studies

of

parenting

behaviors

suggest that fathers still tend to concentrate

their efforts on a handful of basic parenting

responsibilities. Today, fathers roles tend to

be defined by the "Five Ps":

Participator / Problem Solver

Fathers can

sometimes overlook the

importance of being a regular participator in

their child's life. Being there for a child is

more than physical presence, but helping to

meet children's social, emotional, and

psychological needs.

Fathers talk about the importance of

helping their child solve many of the critical

problems of growing up. These could be the

challenges of emerging adulthood such as

deciding: what to do for a living, whether to

go to college, whether to buy a car; or, they

could be everyday tasks such as homework,

fixing a bike, or hanging a swing from a tree.

In the problem-solver role, dads are

modeling effective problem-solving skills for

their child. They have an opportunity to show

their child how to make and act on decisions,

as well as experience the consequences of

their actions and decisions.

This

process

fosters

a

child's

responsibility,

independence,

and

selfreliance. If children are raised without a role

model for effective problem-solving, they

often adopt poor strategies that lead them to

become

ineffectual

and

helpless

in

problematic situations.

Children and adults with deficient

problem-solving skills often become needy

and dependent on others to "make things

right" in their life. On the positive side,

fathers who model healthy problem-solving

in relationships have children who are less

aggressive and who are more popular with

their peers and teachers.

While fathers often play a critical role

in their child's life by setting an example of

problem-solving, fathers sometimes get

involved in solving problems when it's nearly

too late. In some family situations, a father

only gets involved when a child's emotional

and behavioral problems have become so

serious that they are less responsive to

treatment. Reserving dad's help for only the

"big" problems is a big mistake. Fathers need

to be involved in all phases of their child's

problem-solving strategies from serving as

an example to serving as a guide who offers

possible solutions to their children).

Playmate

Fathers can be great jungle gyms.

Research shows that fathers spend more

time, proportionally, with their children in

high-energy, physical play than do mothers.

In addition, fathers tend to engage in more

roughhousing and stimulating play than

mothers, for example, using the elements of

surprise and excitement.

This sets up expectations in children for the

majority of their interactions with fathers

involving physical play.

For example, a daughter hangs on her

father's arm and wants to swing as soon as

he comes through the front door on his way

home from work. Still, this type of play can

be very important in a child's life.

Physical play not only builds muscles and

coordination, but can often be used to teach

rules that govern behavior

(e.g., taking turns, standing in line, playing

physically without injuring someone, etc.).

Through the role of playmate, a father can

encourage his child's sense of autonomy and

independence, which is a major milestone of

social and emotional growth.

In addition, play is often termed a "window to

the child's world." This means that play can

often be used to find out about a child's

thoughts, feelings, hopes, and dreams.

Fathers can also use play to informally start a

serious conversation with their child. In fact,

it's important that fathers

use this time to talk with their child and to

build their emotional bond with them.

Too often, fathers miss this opportunity by

simply playing and substituting physical

contact for verbal interaction

Principled Guide

The clich, "Wait til your father gets home!"

no longer applies due to the diversity of

family types as well as a new understanding

of child discipline as guidance, not

punishment.

Neither should "punisher" be used to

describe a father's role, especially because

punishment tends to be a negative assertion

of adult power. Punishment emphasizes to

children what they should not do, rather than

how parents would like them to act. Also,

punishment may be the result of a parent's

emotional reaction to a childs behavior.

As a result, a child may feel shamed and

humiliated which undermines trust in the

parent-child relationship. Also, the child's

sense of autonomy and initiative may be

undermined, especially when a child's

unacceptable behavior is well-meaning.

Guidance, on the other hand teaches socially

desirable behavior, helps children to learn

the difference between right and wrong, and

enables

children

to

experience

and

understand the consequences of their own

behavior.

Fathers who serve as guides for their children

maintain their authority, but use it

effectively.

Guidance is a collaborative effort between

parent and child that involves an ongoing

process

of

father-child

interaction.

Agreement between fathers and mothers on

guidance strategies is important, particularly

when it comes to learning consequences of

unacceptable behavior. If one parent allows

the child to experience the consequences of

his/her poor decision and the other rescues

the child from that experience, there will be

harmful effects to both the parental

relationship and the child's development.

Just as important, when fathers become

over-involved in punishing, they often have

far too little involvement in rewarding good

behaviors. Fathers who want to build a

healthy bond with their child need to use

appropriate guidance. This guidance must be

a balance between correcting unacceptable

behavior and encouraging with praise and

other rewards for successful behavior.

Provider

While, in the last few decades, mothers of

dependent children have entered the work

force in unprecedented numbers, men

continue to be identified as the primary

"breadwinner" for the family. This is not

always the case, as some fathers choose to

be the primary providers of childcare, for

example, while working out of the home or

continuing their education. Also, with the

increase in divorce and parenting outside of

marriage, many mothers have become the

main providers for their families.

American society still values the ability of the

father to provide tangible resources (i.e.,

food, money, shelter, material possessions)

for their children. For example, policies

enforcing a non-resident father's payment of

child support reflect such values. Also, an

emphasis on responsible fatherhood has

influenced

social

policy

and

social

movements (e.g., the Promise Keepers) in

the 1990s through the new millennium.

More than the provision of material things

(e.g., income and resources) for children and

families, a fathers provider role can be

defined in terms of responsibility for care of

the child. For example, fathers may help to

make plans and arrangements for child care,

even if they are not directly providing care.

All too often, fathers have been led to

believe that providing income and material

support is all there is, their only way for

caring for their family. That's unfortunate,

because

it

discourages

fathers

from

participating in all of the other parenting

activities that many find so fulfilling, such as

guidance, play, and school activities. Further,

if a father values his role as a parent solely

only in terms of providing material resources

for the family, he may begin to feel trapped

by his employment. Placing a bulk of the

emphasis on a fathers being the provider can

prevent his leaving unsatisfying, well-paying

employment. He may not feel able to risk

(even a temporary) decrease in family

income while he looks for other employment

opportunities.

Preparer

Fathers often see themselves as someone

involved in preparing their children for life's

challenges, as well as protecting them when

necessary. They may talk with their child

about family values and morals. Or, fathers

may

advise

their

teenagers

about

educational and employment goals as well as

give advice (when asked for) about peer and

romantic relationships. They may guide their

child about how to behave in school and

work to ensure their child's success in those

areas. They may discuss the importance of

being truthful, of giving an "honest day's

work for an honest day's pay", or showing

their affection to a spouse or partner.

Often, fathers see their relationship with

their child blossom as the child grows into

adolescence and adulthood.

Some fathers even see this as the time to

get involved in preparing their children for

the "real world." In truth, fathers don't need

to wait until their children are becoming

adults in order to teach them important life

lessons. Fathers can provide moral guidance

and practical lessons all the way through

their child's life. This kind of involvement

strengthens the father-child relationship.

Involvement

helps

build

an

ongoing

partnership between father and child. Most

important, through his influence on many

areas of his child's life, a father teaches his

child how to be a parent.

Mothering Role

Mothering is a relationship with a baby or

child characterized by a strong, emotional

attachment that promotes the infant/child's

survival and well being (Barnard, 1995). A

woman's

potential

for

mothering

is

influenced

by

maternal,

infant

and

environmental factors (Mercer, 1981; Rubin,

1984; Koniak-Griffin, 1993) some of which

include:

Quality of mothering she herself

received.

Acceptance of her femininity.

Personal values and goals.

Relationship with the baby's father/

partner and degree of security she derives

from it.

Circumstances surrounding pregnancy

and how welcome it is.

Physical conditions of pregnancy and

delivery.

Circumstances surrounding pregnancy

and how welcome it is.

Physical conditions of pregnancy and

delivery.

Influences on Mothers Capacity

Culture

Adjustment to role as parent of baby

Baby's temperament and special needs

Knowledge of infant behaviors

Support the parent/s receives

Expectations of baby

Relationship with partner

Health of parents and baby

Previous childbirth experience

Spacing between births

Parenting that both parents received

Self-confidence

expectations. Then she imagines herself

performing in that way (projection) and

makes a judgment about the behavior. If the

fit is good, the behavior is accepted.

Reva Rubins Theory: Maternal Role

Attainment. She examined how mothers

use a variety of senses -- sight, smell and

touch -- to become familiar with their

newborns. To encourage the bonding that

she observed, she was an early proponent of

keeping the mother and the newborn

together as much as possible during the first

days after birth. She was the author of "The

Maternal

Identity

and

the

Maternal

Experience" (Springer, 1984). In 1972, she

was a founder with her companion and

longtime professional colleague, Dr. Florence

H. Erickson of the Maternal Child Care

Nursing Journal, the first research journal in

the field. Together, they also established

master's and doctoral programs in nursing at

the University of Pittsburgh. Maternal

identity development is the womans

efforts aimed at becoming a mother

Developmental Stages of Maternal Role

Process of Maternal Role Taking

1. Mimicry- an active operation in which the

woman searches the environment and her

memory for other people who are or have

been in the role she is working to attain, and

then examines their behavior and imitates

them

2. Role play- acting out what a person in the

sought role actually does in particular

situations. the earliest form of role behavior

3. Fantasy- involves cognitively trying

varieties of possible role situations. occurs by

way of fears, dreams, and daydreams

4.Introjection-projectionrejection/acceptance

(IPR/A)- the mother

takes in the behavior of others (introjection),

and examines if it fits her own role

5. Grief work- an operation that has to do

with giving up elements of the former self

which would be in conflict with the new role

A. The Anticipatory Stage: This stage

begins during pregnancy whereby the

woman prepares for her new role. The

pregnant woman prepares for this new role

through

completion

of

four

major

developmental tasks (Rubin,1984).

Maternal Tasks-The totality of a womans

psychologic work of pregnancy. Has been

grouped into four

1. Seeking safe passage for self and baby:

seeking safe passage in the first trimester is

for pregnancy care, in the second trimester it

is for baby care, and in the third it is for

delivery care. Seeking safe passage for

herself and her child through pregnancy,

labor, and delivery.

2.

Securing

acceptance:securing

acceptance is a condition necessary to

produce and sustain the energy for all the

other tasks. involves a reworking of

psychologic, social and physical space within

the family to make a place for the coming

child

3. Learning to give of self: giving is an

inherent and pervasive part of being a

mother,

during

both

childbearing

or

childrearing. the woman has to learn to give

to the child voluntarily on a day-to-day basis

in order for the child to survive

4. Binding-in to the unknown baby: maternal

binding-in is the dynamic process of

attachment and interconnection with the

infant that begins in the prenatal period. has

two halves: binding-in to the infant and

binding-in to self as mother of the infant

B. The Formal Stage

The formal stage begins at birth. During this

stage the new mother needs to complete the

following tasks as part of the process for

acquiring the mothering role (Mercer, 1981)

Maternal Tasks:

1. Reconcile the actual childbirth

experience with her prenatal fantasies

of birth.

As the mother reviews the events of

childbirth and reflects on how they differed

from what she expected, she begins

integrating

the

experience

with

her

expectation. She evaluates her performance

in relation to the experiences of her mother,

sisters, and friends. When the actual

experience is not what was expected, the

mother may feel that her performance was

inadequate. Home visitors can involve

partners in this discussion so that 1) the

mother can receive reassurance and support

about her performance or 2) the experience

can be reframed so that she and the partner

can

recognize

her

strengths

and

accomplishments.

Reconcile pre-birth fantasies of baby

with actual infant characteristics. Talking

about how her baby's characteristics

compare with her fantasies of baby during

pregnancy helps the mother see baby's

uniqueness. Through this process the mother

begins to claim the baby as hers, a step that

is important for sensitive and responsive

care. When baby is the desired sex and has

the

expected

size,

coloring,

and

temperament characteristics, then this task

takes less effort and time and she can move

to other tasks. When there are major gaps

between expectations and reality, there is

more work for mom. Including the partner in

this discussion can help facilitate identity

with and attachment to baby for both mother

and partner.

Reconcile her body image after birth

with her expectations. The new mother

wants to look and feel feminine again. She is

concerned about her appearance. Her

partner's response can assist with this task

or prolong it.

Observe the baby's normal bodily

functions. The new mother needs to see

baby feed, suck, burp, and cry so that she

can be assured that there is nothing wrong

with the baby. This is part of the early

attachment process.

Perform mothering tasks. During the first

two weeks after birth, the first time mother

with no experience focuses on learning and

performing infant care tasks such a bathing,

feeding, burping, and diaper changing. The

experienced mother is concerned with how

to mother this new baby and how the baby

will fit into the family. The experienced, as

well as the inexperienced mother may have

mood swings, be easily frustrated and critical

of herself. Most mothers, regardless of

experience, need reassurance that they are

capable of caring for the new baby.

Redefine partner roles. The new mother

and father begin to redefine their roles as

partners and as parents to include the new

family member.

Resume other responsibilities. Following

birth the mother begins to anticipate the

responsibilities awaiting her at home

including meal preparation, care of older

children, and laundry. The partner can assist

the mother with identifying individuals who

can help them during the early weeks

following birth. Around two weeks after birth,

the mother wants to resume social activities

outside the home. Finding her at home for a

home visit may be difficult after two weeks

as the mother resumes outside activities.

C. The Informal Stage

The informal stage begins during the first

month. The mother creates her own

responses to her baby's cues and relies less

on the advise of experts. The baby's

response to her care and comments from

family members and friends provide the

mother with feedback about her competence

as mother of this baby.

D. The Personal, Maternal Role Identity

Stage

This stage signals the endpoint of maternal

role attainment. During this stage the

mother:

Develops a sense of competence and

satisfaction in the role.

Attaches to the infant.

Is comfortable with her maternal identity.

The timing and duration of these stages are

influenced by a number of factors including

previous mothering experience, culture,

support from significant others, the mother's

physical recovery, the baby's temperament

and expectations of baby.

Ramona T. Mercers Theory 1929-Present:

Maternal Role Attainment- Becoming A

Mother- an interactional and developmental

process occurring over time in which the

mother becomes attached to her infant,

acquires competence in the caretaking tasks

involved in the role. The movement to the

personal state in which the mother

experiences a sense of harmony, confidence,

and competence in how she performs the

role is the end point of maternal role

attainment- Maternal identity

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- COMPREHENSIVE NURSING ACHIEVEMENT TEST (RN): Passbooks Study GuideDe la EverandCOMPREHENSIVE NURSING ACHIEVEMENT TEST (RN): Passbooks Study GuideÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hospice Palliative Care ElectiveDocument3 paginiHospice Palliative Care Electivelemuel_que50% (2)

- The Important Roles of Mothers and Fathers in Child DevelopmentDocument15 paginiThe Important Roles of Mothers and Fathers in Child DevelopmentJerlyn LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- ElectiveDocument2 paginiElectiveMarielle Leyva Aycayde100% (1)

- Maternal and Child Health Nursing: KeepsDocument32 paginiMaternal and Child Health Nursing: Keepsshenric16Încă nu există evaluări

- Head Nurse Job DescriptionDocument2 paginiHead Nurse Job DescriptionGienelle Susana San Juan FerrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prof. AdjustmentDocument111 paginiProf. AdjustmentDianne Kate CadioganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Lesson 1Document8 paginiChapter 1 Lesson 1Aizel ManiagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geria Prelim 1 1Document48 paginiGeria Prelim 1 1SVPSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3-GERIADocument25 paginiChapter 3-GERIA3D - AURELIO, Lyca Mae M.Încă nu există evaluări

- NCM106 Module II Cardiac Failure Nursing CareDocument3 paginiNCM106 Module II Cardiac Failure Nursing CareGrant Wynn ArnucoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus NCM 103 Health AssessmentDocument42 paginiSyllabus NCM 103 Health AssessmentKaye Jean VillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Concepts and Issues in Nursing Lect Hand OutsDocument11 paginiLegal Concepts and Issues in Nursing Lect Hand Outsehjing100% (1)

- Name of Student Grade: Year/ Section/ Group Number: OB Ward Clinical Performance EvaluationDocument3 paginiName of Student Grade: Year/ Section/ Group Number: OB Ward Clinical Performance Evaluationkuma phÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Concepts of Psyche PPt-gapuz OutlineDocument104 paginiBasic Concepts of Psyche PPt-gapuz OutlineIbrahim RegachoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 2 Nursing Care of The Older Adult in WellnessDocument23 paginiLesson 2 Nursing Care of The Older Adult in WellnessSam GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) : Guide For Clinical PracticeDocument79 paginiIntegrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) : Guide For Clinical PracticeCAREZAMBIA100% (1)

- MCN Test DrillsDocument20 paginiMCN Test DrillsFamily PlanningÎncă nu există evaluări

- BioethicsDocument3 paginiBioethicspaui16Încă nu există evaluări

- Ethico - Moral Aspect of NursingDocument37 paginiEthico - Moral Aspect of NursingMarichu Bajado100% (1)

- Sample Evaluative ToolDocument5 paginiSample Evaluative ToolrlinaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practice Test Questions Downloaded From FILIPINO NURSES CENTRALDocument20 paginiPractice Test Questions Downloaded From FILIPINO NURSES CENTRALFilipino Nurses CentralÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Glomerulonephritis (AGN) : Group A Beta Hemolytic StretococcusDocument3 paginiAcute Glomerulonephritis (AGN) : Group A Beta Hemolytic StretococcusKristine Danielle DejeloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Professional AdjustmentDocument3 paginiProfessional Adjustmentkamae_27Încă nu există evaluări

- GCP Format and RulesDocument25 paginiGCP Format and RulesheyyymeeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCM 103 Fundamentals of NursingDocument43 paginiNCM 103 Fundamentals of NursingYzobel Phoebe ParoanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geria UNIT 3Document5 paginiGeria UNIT 3Raiden VizcondeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care of The Older Adult in Chronic IllnessDocument19 paginiNursing Care of The Older Adult in Chronic IllnessWen SilverÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polycythemia Guide: Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentDocument16 paginiPolycythemia Guide: Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentVanessa Camille DomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing LeadershipDocument4 paginiNursing LeadershipClancy Anne Garcia NavalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infertility Nursing Diagnosis and Pregnancy SymptomsDocument7 paginiInfertility Nursing Diagnosis and Pregnancy SymptomsPaolo AtienzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2 Lesson 4Document3 paginiChapter 2 Lesson 4Myla Claire AlipioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comprehensive Examination 10Document8 paginiComprehensive Examination 10명수김Încă nu există evaluări

- Routes of Drug Students)Document5 paginiRoutes of Drug Students)yabaeve100% (1)

- College review education programDocument8 paginiCollege review education programMcbry TiongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laws Affecting Nursing PracticeDocument33 paginiLaws Affecting Nursing Practiceapi-2658787980% (5)

- Prepared By: Mylene Karen B. Pueblas, RNDocument136 paginiPrepared By: Mylene Karen B. Pueblas, RNmylene_karen100% (2)

- Cancer Burden: Global Picture. Number of New Cancer Cases (In Millions)Document5 paginiCancer Burden: Global Picture. Number of New Cancer Cases (In Millions)Samantha BolanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHN Lecture June 2012Document27 paginiCHN Lecture June 2012Jordan LlegoÎncă nu există evaluări

- NLM Sas 8Document6 paginiNLM Sas 8Zzimply Tri Sha UmaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCM103 (FUNDA) Module 1 Concept of NursingDocument4 paginiNCM103 (FUNDA) Module 1 Concept of NursingJohn Joseph CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCM 118Document14 paginiNCM 118joan bagnateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals of NursingDocument4 paginiFundamentals of Nursingchowking10Încă nu există evaluări

- Individual Rotation PlanDocument3 paginiIndividual Rotation PlanMel RodolfoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment Leadership Community Health 4 1Document14 paginiAssessment Leadership Community Health 4 1Royal Shop100% (1)

- Code of Ethics For Registered Nurses Board ofDocument21 paginiCode of Ethics For Registered Nurses Board ofraven riveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing History and ConceptsDocument15 paginiNursing History and ConceptsEm IdoÎncă nu există evaluări

- FNCP On Elevated Blood Pressure 2Document4 paginiFNCP On Elevated Blood Pressure 2Aaron EspirituÎncă nu există evaluări

- AMIDocument44 paginiAMIsjamilmdfauzieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preoperative Surgical NursngDocument271 paginiPreoperative Surgical NursngPaw PawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Care of Older Person with Chronic IllnessDocument87 paginiCare of Older Person with Chronic IllnessKristine KimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transcultural Perspective in The Nursing Care of Adults Physiologic Development During AdulthoodDocument5 paginiTranscultural Perspective in The Nursing Care of Adults Physiologic Development During AdulthoodeuLa-mayzellÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3c-Abas, Alexander Miguel M. (Ncm117 Rle - Self-Awareness Activity)Document5 pagini3c-Abas, Alexander Miguel M. (Ncm117 Rle - Self-Awareness Activity)alexander abasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Care of The Chronically Ill and The Older PersonDocument109 paginiCare of The Chronically Ill and The Older PersonJennifer Gross100% (3)

- Philosophy and Theoretical Framework of Community Health NursingDocument9 paginiPhilosophy and Theoretical Framework of Community Health Nursingᜀᜇᜒᜐ᜔ ᜇᜒᜎ ᜃ᜔ᜇᜓᜐ᜔Încă nu există evaluări

- Bioethical Components of CareDocument2 paginiBioethical Components of CarekeiitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community Health Nurse RolesDocument4 paginiCommunity Health Nurse Rolescoy008Încă nu există evaluări

- Geria Part 1Document16 paginiGeria Part 1Hannah Leigh CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Limitations On The Power of TaxationDocument3 paginiLimitations On The Power of TaxationanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peer Assessment and TutoringDocument7 paginiPeer Assessment and TutoringanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment in Learning 1Document15 paginiAssessment in Learning 1ana82% (17)

- The Everyday Lives of MenDocument207 paginiThe Everyday Lives of MenanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sexualbehavior 160303172550 PDFDocument20 paginiSexualbehavior 160303172550 PDFanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Parkland Formula Is The Most Commonly Used Formula For Computing The Fluid Replacement For BurnsDocument2 paginiThe Parkland Formula Is The Most Commonly Used Formula For Computing The Fluid Replacement For Burnsana100% (1)

- JUNE 2008 NP1 BOARD EXAM QUESTIONSDocument70 paginiJUNE 2008 NP1 BOARD EXAM QUESTIONSPrecious Nidua100% (1)

- Making The Most of The Budget CycleDocument3 paginiMaking The Most of The Budget CycleanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Making The Most of The Budget CycleDocument3 paginiMaking The Most of The Budget CycleanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eisners Connoisseurship ModelDocument8 paginiEisners Connoisseurship ModelanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overview of Budget Formulation ProcessDocument2 paginiOverview of Budget Formulation ProcessanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Education 170 ItemsDocument29 paginiGeneral Education 170 ItemsanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles in Evaluation of A CuricculumDocument3 paginiPrinciples in Evaluation of A CuricculumanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Positioning ClientsDocument2 paginiPositioning Clientsana100% (1)

- Writing Tips for TestsDocument4 paginiWriting Tips for TestsanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curr Eval CKLDocument9 paginiCurr Eval CKLJhamie MiseraleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dep EdDocument1 paginăDep EdanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AdminLaw DeLeonDocument17 paginiAdminLaw DeLeonOwen Buenaventura100% (1)

- Budget Formulation: Challenges For The Health SectorDocument10 paginiBudget Formulation: Challenges For The Health SectoranaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Latest DepEd Policy On The Recruitment and Deployment of Public School TeachersDocument3 paginiThe Latest DepEd Policy On The Recruitment and Deployment of Public School Teachersana91% (34)

- Tra 0000042Document8 paginiTra 0000042api-359742580Încă nu există evaluări

- How Love, Attraction and Relationships DevelopDocument48 paginiHow Love, Attraction and Relationships DevelopanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft Actteacherspartylist Magna Carta For Private School TeachersDocument12 paginiDraft Actteacherspartylist Magna Carta For Private School TeachersRhea Pardo PeralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Budgetingppt 141024030031 Conversion Gate01Document45 paginiBudgetingppt 141024030031 Conversion Gate01anaÎncă nu există evaluări

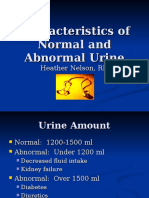

- Characteristics of Normal and Abnormal Urine 869Document12 paginiCharacteristics of Normal and Abnormal Urine 869RakeshSenwaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Federal Momentum Budget Formulation ExecutionDocument2 paginiFederal Momentum Budget Formulation ExecutionanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbdomenDocument2 paginiAbdomenanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abnormalities of StoolDocument9 paginiAbnormalities of StoolanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common Abnormalities AbdomenDocument4 paginiCommon Abnormalities AbdomenanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Korotkoff SoundsDocument1 paginăKorotkoff SoundsanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course File Format For 2015-2016Document37 paginiCourse File Format For 2015-2016civil hodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Esra SİPAHİ National Ministry of Education, Business Administration, Ankara, TURKEYDocument8 paginiDr. Esra SİPAHİ National Ministry of Education, Business Administration, Ankara, TURKEYCIR EditorÎncă nu există evaluări

- MOOC 4 Negotiation GameDocument1 paginăMOOC 4 Negotiation GameRoberto MorenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kester, Lesson in FutilityDocument15 paginiKester, Lesson in FutilitySam SteinbergÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math Fall ScoresDocument1 paginăMath Fall Scoresapi-373663973Încă nu există evaluări

- Grade 3 ReadingDocument58 paginiGrade 3 ReadingJad SalamehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zambia Weekly - Week 38, Volume 1, 24 September 2010Document7 paginiZambia Weekly - Week 38, Volume 1, 24 September 2010Chola MukangaÎncă nu există evaluări

- G Power ManualDocument2 paginiG Power ManualRaraDamastyaÎncă nu există evaluări

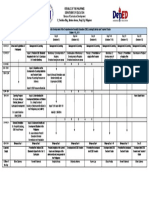

- Department of Education: Grade & Section Advanced StrugllingDocument4 paginiDepartment of Education: Grade & Section Advanced StrugllingEvangeline San JoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- h5. Communication For Academic PurposesDocument5 paginih5. Communication For Academic PurposesadnerdotunÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Draw Portraits (Beginner Starting Point) - Leveling ArtistDocument10 paginiHow To Draw Portraits (Beginner Starting Point) - Leveling Artistluiz costa guitarÎncă nu există evaluări

- UNESCO, Understanding and Responding To Children's Needs in Inclusive Classroom PDFDocument114 paginiUNESCO, Understanding and Responding To Children's Needs in Inclusive Classroom PDFIvanka Desyra SusantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Following Text Is For Questions No 1 To 3. Should People Shop in Online Shop?Document5 paginiThe Following Text Is For Questions No 1 To 3. Should People Shop in Online Shop?lissa rositaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPC Practice Exam - Medical Coding Study GuideDocument9 paginiCPC Practice Exam - Medical Coding Study GuideAnonymous Stut0nqQ0% (2)

- Earthquake Proof Structure ActivityDocument2 paginiEarthquake Proof Structure ActivityAJ CarranzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- fomemasdnbhd: Call CenterDocument4 paginifomemasdnbhd: Call CenterjohanÎncă nu există evaluări

- NAVMC 3500.89B Ammunition Technician Officer T-R ManualDocument48 paginiNAVMC 3500.89B Ammunition Technician Officer T-R ManualtaylorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final - CSE Materials Development Matrix of ActivitiesDocument1 paginăFinal - CSE Materials Development Matrix of ActivitiesMelody Joy AmoscoÎncă nu există evaluări

- BASIC MATH - Drawing A PictureDocument26 paginiBASIC MATH - Drawing A PicturePaul WinchesterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structure, Function and Disease ADocument19 paginiStructure, Function and Disease AJanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhu BSCDocument1 paginăBhu BSCShreyanshee DashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sy 2019 - 2020 Teacher Individual Annual Implementation Plan (Tiaip)Document6 paginiSy 2019 - 2020 Teacher Individual Annual Implementation Plan (Tiaip)Lee Onil Romat SelardaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Watercolor Unit Plan - Olsen SarahDocument30 paginiWatercolor Unit Plan - Olsen Sarahapi-23809474850% (2)

- Form 137 Senior HighDocument5 paginiForm 137 Senior HighZahjid Callang100% (1)

- Ghotki Matric Result 2012 Sukkur BoardDocument25 paginiGhotki Matric Result 2012 Sukkur BoardShahbaz AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Director Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanDocument3 paginiDirector Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanSamuelDonovanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quarter 2 - Module 2 - Sampling Techniques in Qualitative Research DexterVFernandezDocument26 paginiQuarter 2 - Module 2 - Sampling Techniques in Qualitative Research DexterVFernandezDexter FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elm 375 Formal Observation ReflectionDocument2 paginiElm 375 Formal Observation Reflectionapi-383419736Încă nu există evaluări

- Walter BenjaminDocument15 paginiWalter BenjaminAndrea LO100% (1)

- David Edmonds, Nigel Warburton-Philosophy Bites-Oxford University Press, USA (2010) PDFDocument269 paginiDavid Edmonds, Nigel Warburton-Philosophy Bites-Oxford University Press, USA (2010) PDFcarlos cammarano diaz sanz100% (5)