Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in The Broad Translation Quality Debate

Încărcat de

IJ-ELTSTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in The Broad Translation Quality Debate

Încărcat de

IJ-ELTSDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

[PP: 143-158]

Wanchia T. Neba, PhD

ASTI, University of Buea

Cameroon

ABSTRACT

Beyond revisiting the byzantine and seemingly inconclusive debate on translation quality assurance and

assessment, this article investigates the extent of an across-the-board applicability of existing quality

assessment frameworks to the broad translation quality debate, against a strong backdrop of culturespecificity. It, first and foremost, exemplifies cultural and literary specificity through linguistically openended African creative writing, examines the variegated concept of translation, the volatile concept of

translation quality assurance and assessment, outlines constraints to the assurance and assessment of this

translation quality, and importantly portrays the preponderant place of metrics, rubrics and models in quality

assurance and assessment. Secondly and finally, using a blend of literary and translation theories and

strategies, it then qualitatively demonstrates from existing evidence, that quality assurance with its

acquiesced formulae will continue to be at the mercy of incontestable contextualised cultural specificity

being of necessity a provincialised and balkanised activity.

Keywords: Cultural specificity; translation as variegated concept; translation quality; rubrics and models;

creative writing; translation quality, provincialisation/ balkanisation

ARTICLE The paper received on: 30/07/2015 , Reviewed on: 30/08/2015, Accepted after revisions on: 19/10/2015

INFO

Suggested citation:

Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate. International

Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from http://www.eltsjournal.org

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

1. Introduction

Discussing quality in translation has

happened as if quality assurance and

assessment were a disease that could be

eradicated by a simple universal therapy,

whose main ingredients are the gamut of

principles, theories, strategies, etc, floated in

Translation Studies textbooks. Yet, while the

universal applicability of principles, theories,

and strategies is possible with texts of

typically technical and pragmatic nature,

such becomes highly diminished as the text

type becomes more and more cultural. In a

qualitative manner, this write-up investigates

the degree to which an

all-embracing

applicability of existing quality assessment

frameworks continuous to be possible,

especially against a strong backdrop of

growing

culture-specificity

and

consciousness. A discussion of the intricate

African literary and cultural text that now

increasingly demands special attention

during translation is preceded by a review

and focus on the concepts relevant to the

understanding of these issue under

examination.

2. Literature Review

African cultural and literary specificity,

the variegated concept of translation, the

translation process, the issue of translation

quality, translation quality assurance and

assessment, constraints to translation quality

assurance and assessment, as well as

translation quality assurance frameworks

constitute the menu of this review.

2.1 African cultural and literary specificity

It is an inviolate fact in Translation

Studies that cultural specificity influences

how translation quality is constructed. The

issue of African cultural and literary

specificity has been stated, discussed and

affirmed by scholars both from within and

out of African, as exemplified in the

following background considerations:

a) First and foremost, there is specificity on

account of orality: Okara (1973, p.137-138)

posits that

African ideas, philosophy,

folklore and imagery help to keep as close as

possible to vernacular expressions, and thus

do more adequately express African ideas

and thoughts (and not those of the other

European). Kourouma (as cited in Kon,

1992, p. 83) declares that while thinking first

in his native Malinke before writing in

French, he exercises boundless liberty,

cassant le franais pour trouver et restituer

le rythme africain, [breaking up the French

language in order to recreate an African

rhythm]. With specific reference to

Cameroon, Ndzana (1988, p. 147-151), (just

like Ndzi, 1985, p. 344, as cited in Fofi,

2007, p. 54) adds that la culture

camerounaise semble privilgier la langue

parle, vivante, orale au dtriment de la

langue crite, classique, normativement

bonne [Cameroonian culture seems to

prefer spoken, living, oral language to the

detriment of written, classical and

normatively

good

language],

(my

translation). Finally, Bandia (1993, p. 55)

avers that

It is generally agreed that African creative

writing in European languages has been

greatly influenced by African oral tradition

(Obiechina, 1975; Chinweizu et al, 1980;

Grard, 1986; Bandia, 1993).

Okpewho (1992, p. 70-104) then outlines

the unique stylistic qualities of African

literary works to include repetition,

parallelism, piling and association, tonality,

ideophones, digression, imagery, allusions,

and symbolisms which are all akin to oral

tradition.

b) Secondly, peculiarity of spontaneity:

Spontaneity refers to behaviour that is natural

and unconstrained and is the result of impulse

and not planning (Microsoft Encarta, 2009).

In Africa, spontaneity is a common literary

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 144

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

hallmark. With respect to popular

performances, Okpewho (1992, p. 33) opines

that

sometimes,

composition

and

performance happen simultaneously and the

artist has the outstanding job of

bestowing, totally unrehearsed, a traditional

pattern of imagery and diction on a brandnew subject, showing rather impressively

how in African the acts of composition and

performance can take place simultaneously

(Okpewho, 1992, p. 34).

c) Thirdly, peculiarity of creativity:

Creativity refers to the use of skill and

the imagination to produce something

new or a work of art (Oxford Advanced

Learners Compass) or showing use of

the imagination to create new ideas or

things (Microsoft Encarta, 2009).

Despite the fact that African art in general

is a communal activity, creative

idiosyncratism is still very present.

Darah (1982, p. 1, as cited in Okpewho,

1992, p. 32) asserts that

A gifted Ororile creates by deft of allusions

and analogy. As the song progresses,

metaphors are introduced. Once a

metaphorical remark or proverbial allusion

is made and explained logically later in the

song, then that piece is acclaimed a

successful one.

Okpewho buttresses Daras idea by stating

that:

The principal stylistic tools of this job are

metaphor, allusion, analogy, and other kinds

of oblique imagery designed to make it

reasonably clear who the subjects are even

when fake names are used (Okpewho, 1992,

p. 32).

d) Fourthly, peculiarity of paralinguistic

artistry: Paralinguistic artistry refers to

the accompanying resources variously

described as

nonverbal,

extraverbal,

paraverbal,

paratextual, or paralinguistic, in the sense

that they occur side by side with the text or

the words of the literature..One of these

resources is the histrionics of the

performance, that is, movements made with

the face, hands, or any other part of the body

as a way of dramatically demonstrating an

action contained in the text (Okpewho, 1992,

p. 46).

e) Fifthly, peculiarity of punning/wordplay

(and tongue-twisters): Delabastita posits

that:

Wordplay is the general name for the various

textual phenomena in which structural

features of the language(s) used are

exploited in order to bring about a

communicatively significant confrontation

of two (or more) linguistic structures with

more or less similar forms and more or less

different meanings (Delabastita, 1996, p.

128).

Though considered a global phenomenon,

unique puns and wordplay abound in African

literary art (Bjornson, as cited in Newell,

2002, p. 74) and Fofi (2007).

f) In sixth position, there is peculiarity of

linguistic hybridization /assortment:

Vakunta (2008, p. 942) posits that

African creative art consists of texts

couched in indigenized and hybridized

linguistic forms, namely creoles, pidgins,

camfranglais, and other forms of hybrid

languages. For him, it is an all-African

phenomenon in that

Africans of all backgrounds use blended

languages such as Camfranglais, Pidgin,

Moussa and Nouchis as a means of ensuring

group solidarity within a community of

practice. Creative writers use these mixed

varieties to translate the socio-cultural

contexts that inform and structure their

narratives (Vaktuna (2008, p. 946).

Gyasi (1999, as cited in Vakunta, 2008, p.

946), describes this as a creative translation

process that leads to the production of an

authentic African discourse (a third hybrid

code) that requires non-speakers to refer to

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

Wanchia, T. N

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Page | 145

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

the writers native language and culture for

signification. Evembe (1988) as well as

Ndzana (1988, p. 153) further signal an even

more complex phenomenon of language

assortment/medleying on the continent,

which Suh (2005) qualifies as an ambivalent

situation of the use of double language.

g) Finally, peculiarity of humour: Humour,

as a meaning effect with incontestable

exteriorised manifestation like laughter

or smiling, is one of Africas major

literary aesthetic tenets. Humour abounds

in the works of Afana, Kouokam (Fofi,

2007) and a host of other African artists

(Bjornson, as cited in Newell, 2002).

Vandaele (2002, p. 150) particularly

opines that from a practice perspective the

appreciation of humour varies with

individuals as what is humorous for one

person, for instance, may just be a comic/bad

joke and therefore not really funny enough

for another. This is extrapolatable to the

wider cultural group, for after all culture is

both individual and societal. This is

particularly problematic to translation

(Attardo, 1994, p. 173-193; Antonopoulou,

2002, p. 195-220; and Vandaele, 2002).

At a time when the concept of translation

itself remains very brain-bugging, the

translation of the above traits as well as the

quality resulting therefrom calls for special

attention, especially, with specific reference

to African creative writing.

2.2 Translation: a variegated difficult-todefine concept

Conceptualizing translation has been

long,

ink-spilling,

and

ostensibly

inconclusive. But far beyond the platitude of

reciting the entire array of scholarly

definitions of translation responsible for the

difficulty to have a common definition, this

article rather attempts to appraise how far

varied perspectives contribute to the

translation quality assessment debate.

Vinay & Darbelnet (1959, p. 20); Catford

(1965, p. 4); Tweney & Hoeman (1976, p.

138); Brislin (1976); Ladmiral (1979, p. I);

Crystal (1987, p. 344); Newmark (1981, p.

7); Hewson & Martin (1991); Steiner (1992,

p. 253); and Snell-Hornby (1994, p. 4-5)

reveal that the different perceptions about

what translation really is have largely been a

function of whether scholars perceive it as an

art, discipline, process, product or

profession. The complexity of the concept is

better expressed by the following quotes:

a) the purposes of translation are so diverse and

the texts so different and the receptors are so

varied that one can readily understand how

and why many distinct formulations of

principles of translation have been proposed

(Nida, 1977, p. 67);

b) despite the numerous works on the subject,

translation remains a complete obfuscation,

something that requires the empirical rigour

of the linguist, the perspicacity of the literary

critic and voraciousness of the philosopher

all in combination in a single proposed

solution to the problem of translation

(Frawley, 1984, p. 11); and

c) translation is a widely diverging and

frustratingly empirical issue, given that

theoretical reflectionappears plethoric,

repetitive, and generally unproductive

(Hewson & Martin, 1991, p. 2). They further

enquire if there are any specific reasons for

this confusion and for the breach between

theory and practice?

Beyond and above all controversies, Ali

Darwish (1999/2001, p. 13) thinks the

fundamental issue in conceptualising

translation remains the quest for quality and

the desire to preserve original meaning

when it is conveyed or converted into the

target languages verbal expression. Yet, it

is still common knowledge that preserving

and keeping control of original meaning that

ensures the integrity of information is

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 146

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

intrinsically difficult given that in the

transformations of the translation process,

there is inherent loss of information. How

then can quality be preserved when the

tendency to lose control of original meaning

is so real?

2.3 The issue of translation quality

The immense difficulty in defining

translation undoubtedly directly impinges on

the task of assuring and assessing quality.

ISO 8402 (1994, 3.1), amongst many

stakeholders, avers that quality is the totality

of features and characteristics of a product or

service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated

or implied needs. Muzii (2006) also sees

quality as an integration of the features and

characteristics that determine the extent to

which output satisfies the customers needs.

Quality therefore implies the existence of

defects, defined by ISO (1994, 3.1) as the

non-fulfilment

of

intended

usage

requirements. Defects can be minimised if

some attention is paid to the translation

process itself.

2.4 The

translation

process

vi--vis

translation quality

Whereas Bell (1987) deplores the

tendency to ignore the process involved in the

act of translating, most translation scholars

still erroneously treat the translators

competence, the translation process and the

resultant quality, as disconnected entities. In

the same light, Ali Darwish (1999) laments

that no study so far has really tackled the

issue of process in a more pragmatic fashion.

Owing to the perplexity and intertwining

between aspects of the translation process,

Bell again avers that

if we treat texts merely as a self-contained

and self-generating entity, instead of as a

decision-making procedure, and an instance

of communication between language users,

our understanding of the nature of

translating will be impaired (Bell, 1987, p.

403-415).

Notwithstanding the important work

done on the translation process - which

constitutes i) evidence of a transaction, ii) a

means of retracing the pathways of the

translators decision-making, and iii) an

instance of communication between

language users, the process has unfortunately

remained in dire want of delineation (Ali

Darwish, 2001, p. 8). This, unquestionably,

affects discussions on what quality assurance

and assessment ought to be.

2.5 Translation quality assurance and

assessment

After perceiving quality assurance (QA)

as the act of maintaining translation services

to ensure conformance to customer

requirements or other specifications,

Gerasimov (2005, p. 1) posits that it is

implemented by the translation service

provider. He continues that QC (quality

control) is implemented by your customer

after the translation is completed and

delivered. According to Muzii (2006),

quality control (QC) is an integration of the

features and characteristics that determine the

extent to which output satisfies the

customers needs.

Because

translation quality today

remains marred by impressionistic and often

paradoxical judgments based on elusive

aesthetics (Al-Qinai, 2000, p. 497), Ali

Darwish (2001, p. 2) then clearly cautions

that without well-defined assessment and

evaluation standards and processes, quality

assessment and assurance will always be

haphazard and subject to the personal

preferences and whims of the individual

assessor or the interpretive frameworks,

bureaucratic perspectives and draconian

measures of educators and evaluators alike.

This is true, because translation is a highly

constraint-ridden hermeneutic exercise!

2.6 Constraints to translation quality

assurance and assessment

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

Wanchia, T. N

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Page | 147

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Ali Darwish (1999) asserts that the

ultimate goal of any translation strategy is to

manage to remove possible general and

specific constraints to translatability, and that

appreciating not only how these constraints

function but equally how they can be

managed and ideally removed within a model

or framework of constraint management is of

benefit to translation quality stakeholders.

a) General theoretical translatability

constraints: Bassnett opines that

translation is very obstacle-ridden,

irrespective of whether it is the

professional or amateur translator

concerned. She further avers that

all kinds of different criteria come into play

during the translation process and all

necessarily involve shifts of expression as the

translator struggles to combine his own

pragmatic reading with the dictates of the

TL cultural system (Bassnett, 1991, p. 104).

From the perspective of pre-translation

quality quest, Hatim & Mason (1994, p. 3-20)

outline general theoretical constraints

reflected by the following inexhaustive

categories that must be seriously metered by

the translator (the vital communicative

problem-solver), if s/he intends to attain

acceptable quality. They include the process

vs. product (Bell, 1987; Hatim & Mason,

1994, p. 4); objectivity vs. subjectivity (Reiss,

1971/77; House 1976; Wilss, 1982); literal

vs. free translation (Hatim & Mason, 1994,

p. 5; Newmark, 1988, p. 68-69); formal vs.

dynamic equivalence (Nida, 1964, p. 160);

form and style vs. content (Meschonnic;

1973, p. 349; Hatim & Mason, 1994, p. 8;

Nida, 1964, p. 169); redefining style (Hatim

& Mason, 1994, p. 9); meaning potential

(Halliday, 1978, p. 109; Beaugrande, 1978);

empathy

and

intent;

translators

motivation; translating centre; and

conditions of production ( all cited in Hatim

& Mason, 1994).

b) Specific translatability constraints: In

addition to the above general theoretical

considerations against which the

translators purpose, priorities, and

output are judged, other specific

constraints have also been identified.

According to Boase-Beier & Holman

(1988) they include conceptual (1988, p.

2); external (1988, p. 10 & 72);

phonological (1988, p. 5-6); literary

(1988, p. 5); political and ideological

(1988, p. 5); syntactic and stylistic (1988,

p. 6); and personal, that is,

Upbringing,

education,

knowledge,

sensibilities, predilections and beliefs also

contribute to the formation of the individual

personality of the translator, limiting,

defining, and also facilitating the translation

process, from the initial selection of the SL

text right the way through to the final release

into the world of its TL progeny [1988, p.

8-9]);

Other scholars add the contextual and

socio-cultural (Hatim & Mason, 1990, p. 37);

textual (Kress, 1985, p. 12); Hatim & Mason,

1998); linguistic and formal (Hatim &

Mason, 1990:192; Saussure 1916); and

conventional (Bassnett, 1991, p. 104).

In the face of all these constraints,

metrics, rubrics and models have been

fashioned in guise of frameworks to enhance

quality attainment.

2.7 Translation

quality

assurance

frameworks

According to Muzii (2006), the best way

to assess quality is to measure the number and

magnitude of defects whose features and

scope must be specified by metrics, rubrics

and models.

a) Translation quality metrics: We agree

with Sir William Thomson (1883, cited in

Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol.

4, [MUP], 1972) that:

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 148

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

When you can measure what you are

speaking about, and express it in numbers,

you know something about it; but when you

cannot

express it in numbers, your

knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory

kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge,

but you have scarcely in your thoughts

advanced to the state of science.

In this same vein, and with respect to

translation, Muzii (2006, p. 22) opines that

The best way to assess quality remains that of

measuring the number and magnitude of

defects; and when defects cannot be

physically removed, their features and scope

must be specified.[... ] The first step, then, is

to establish a model of definition of quality,

and translate it into a set of metrics that

measure each of the elements of quality in it.

Despite the above viewpoints, there has

been lack of any serious definition of quality

or provision of any real metrics, except for

Baker (1992), Zlateva (1993), House (1997)

and Schffner (1998) who from the early 90s

veritably started talking invariably of

components, aspects and factors of quality

such as accuracy, precision, correctness,

faithfulness, etc. But metrics were certainly

judged inadequate, so came the turn of

rubrics!

b) Translation quality rubrics: Another

attempt at resolving the problem of

translation quality assurance and

assessment has been from the perspective

of rubrics which Riazi (2003, cited in

Khanmohammad & Osanloo, 2009, p.

131-153) describes as an attempt to

delineate consistent assessment criteria.

He emphasizes that it enables teachers

and students alike to assess criteria which

are complex and subjective and also

provide basis for self-evaluation,

reflection, and peer review. Today, four

existing rubrics include those by

Farahzad (1992), Waddington (2001),

Sainz (1992), Beeby (2000), and Goff-

kfouri (2005). From these, a detailed

component-centred rubric that takes into

account different aspects of translation

(comprehension, conveyance of sense

and style, inter alia) has seen the light of

day, highlighting

accuracy (30%);

suitable word equivalence in target text

(25%); target texts genre, target

language culture (20%); grammar and

style (15%); shifts (8%); and addition,

omission and inventing equivalents (7%).

For Khanmohammad & Osanloo (2009,

p. 149) this is

an empirical rubric for translation quality

assessment based on objective parameters of

textual typology, formal correspondence,

thematic coherence, reference cohesion,

pragmatic equivalence, and lexico-syntactic

properties [and] can serve translation

instructors in order to come up with a more

objective assessment of students translation

works. Students majoring in translation can

also benefit from the findings of this study too

since they would certainly be able to improve

their translations if they were aware of the

comprehensive criteria used to evaluate their

translations.

c) Translation quality models: Only those

of House (1976-2001), Al-Qinai (2000),

and Ali Darwish (2001) - amongst many

are visited.

i) House, 1976 - 2001: House is credited

with the first effort to examine translation

quality in depth through a model, inspired

by Nida (1964), Toury (1995), Venuti

(1995), Catford (1965), Reiss (1971),

Wills (1974), Baker (1992), Hatim &

Mason (1997), and Hickey (1998).

Houses model (1997) is, properly

speaking, Hallidayan systemic-functional

theory-based, drawing much from the

Praque School, speech act theory,

pragmatics, discourse analysis and

corpus-based distinction between spoken

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

Wanchia, T. N

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Page | 149

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

and written language. House (1997, p.

251) posits that

Translation criticism therefore has two

basic functions, an ideational function and an

interpersonal function. These two functions

have their counterpart in two different

methodological steps. The first and in my

estimation, the primary one, refers to

linguistic-textual

analysis,

description

explanation, and comparison, and it is based

on empirical research and professional

knowledge of linguistic structures and norms

of language use. The second step refers to

value judgements, social, interpersonal and

ethical questions of socio-political and sociopsychological relevance, ideological stance

or individual persuasion. Without the first,

the second is useless we have to make

explicit the grounds for our judgement basing

it on a theoretically sound and argued set of

intersubjectively verifiable set of procedures.

However, despite the above intense

intellectual exercise, House fails to pointedly

name the verifiable sets of procedures. And

she is aware of this when she avers that it

seems unlikely that translation quality

assessment can ever be objectified in the

manner of natural science. This is why other

models are necessary!

ii) Ali Darwish, 1999-2001: Ali Darwish

considers translation and translation

quality as a

rational objective-driven, result-focused

process that yields a product meeting a set of

specifications, implicit or explicit. If

translation is a haphazard activity, it falls

outside the scope of quality assurance

principles that are based on rationality of

process and consciousness of decisionmaking (Ali Darwish, 2001, p. 5).

iii) Al-Qinai 2000: For his part, Al-Qinai

(2000, p. 499) embarked on the search for

a model of quality assurance and

assessment

based

on

objective

parameters of textual typology, formal

correspondence, thematic coherence,

reference

cohesion,

pragmatic

equivalence

and

lexico-syntactic

properties. This eclectic practical model

targets

textual/functional

or

pragmatic

compatibility (i.e. quality of linguistic

conversion) rather than the logistics of

management and presentation (i.e. quality of

service). After all, the ultimate end-users are

interested in the quality of the product and

not the means sought to serve its creation

(Al-Qinai, 2000, p. 499).

If one agrees with Muzii (2006) that a

comprehensive set of metrics must measure

quality from several points during the

production process regardless of the model,

then the standpoints of House, Ali Darwish

and Al-Qinai should be considered as being

more complementary than antagonistic. Yet,

all said and done, the applicability of these

metrics, rubrics and models to translation

quality assurance and assessment, especially

against the backdrop of culture specificity

remains quite contentious. The circuitous

relationship between translation quality and

African cultural and literary specificity which

now

requires

special

attention

is

demonstrated in the procedures below.

3. Methodology

Four frameworks - the conceptual,

contextual, theoretical, and procedural guide this demonstration.

a) This article conceptually relies on

culture-specificity,

the

variegated

concept of translation, translation quality,

the translation process, and quality

assurance and assessment as concepts

that weave together the discussion.

b) Contextually, African cultural and

literary specificity in the broad translation

quality assessment debate continues to

occupy centre stage especially following

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 150

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

the relevant viewpoint of the role of

context in translation. Bassnett (1993, p.

160-61) posits that

Writing does not happen in a vacuum, it

happens in a context and the process of

translating texts from one cultural system

into another is not a neutral, innocent,

transparent activity. Translation is instead a

highly charged, transgressive activity and the

politics of translation and translating deserve

much attention than has been paid in the past.

Bassnett (1998a, p. 123) further avers that

The study of the practice of translation has

moved from its formal phase and is beginning

to consider broader issues of context, history

and convention called the cultural turn in

translation studies. Klimenko (2004, p. 215229) then affirms that paying attention to

context and other extra-textual practices is

crucial if one is to respect the demands of the

new philosophy of culture-consciousness.

These considerations justify the discussion in

time and space.

d) Theoretically, the following literary/text

criticism approaches and translation

theories have proven useful to this

discussion.

i) The main tenets of literary/text criticism

approaches such as the cultural

(Robinson, 1988, p. 11); intercultural

(Kim, 1988, p. 12); deconstruction

(Varney, 2008, p. 116); sociological

(Scott, 1962, p. 126); formalistic

(Jakobson, 1989, p. 26); and semiotic

approaches. (Pavis, (1976, p. 5) are

applicable in this study.

ii) In the same vein, translation theories such

as the linguistic (Nida, 1982, p. 69);

philological (Nida, 1982, p. 67-69);

sociolinguistic (Nida, 1982, p. 77);

textlinguistic (Wilss, 1982, p. 113);

semiotic (Bassnett, 1980/1991, p. 13,

cited in Baker, 1998, p. 218); and skopos

(Vermeer, 1989/2000) have been

considered.

c) Procedurally, data comes from Les

soleils des indpendances (Kourouma,

1970) because:

i) Firstly, the excerpts possess the traits of

African cultural and literary peculiarity,

ii) Secondly, they are representative of the

literary, and ideological views of other

authors (Achebe, 1958/1994); Oyono,

1956); and Ngugi (1965/1989)

iii) Thirdly, the choice is equally guided by

the fact that the translations of these

works are generally accepted in their light

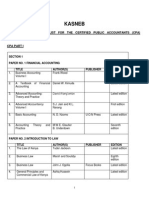

(Adams (1981, in Table 1 below),

iv) Finally,

that despite the general

acceptability of their translations, many

scholars have continued to clamour for a

review of certain translated sections that

misrepresent the authors culture-specific

vision (Adams (1981, in Table 2 below).

The data that is qualitatively analysed

below makes use of an eleven-step grid

considered to be largely in tune with

Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS)

criteria (Toury, 1995).

4. Data Presentation and Analysis

The various steps for this analysis include

stating the source text, context of production,

element(s) of interest, intended standard

expression, peculiarity of item, target text,

translators strategy and theory, value

judgement, proposed translation, strategy of

proposed translation and justification, theory

used in proposed translation, in that order.

From these chronological steps, the excerpt

in Table 1 (Kourouma, 1970, p. 15 for

French, and p. 8 for English) is succinctly

described, explained and analysed to show

an accepted translation while Table 2

(Kourouma, 1970, p.13 for French, and p. 6

for English) is judged unsuccessful, and thus

in want of improvement (Akrobou, 2006;

2013; Ngeng, 2015).

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

Wanchia, T. N

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Page | 151

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Table 1: Successfully translated Africanised excerpt

Table 2: Unsuccessfully translated Africanised excerpt, with corrections

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 152

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

5. Findings

The above excerpts which meet the seven

traits of African cultural and literary

peculiarity outlined earlier on in this article

are a conspicuous example of Malinke

indigenous thought pattern and expression.

For instance, the verb se casser in Table 2 as

used in the source text deviates from its

dictionary meaning in French. Though

usually used to talk of inanimate objects, the

author uses it for an animate object - a sort of

direct translation of the way it is said in

Malinke. The language is simple but

dignified and characters use an elevated

diction meant to convey the sense of

indigenised speech which leaves one with a

sense of listening to another tongue,

emanating from a rich and valuable tradition.

Normatively, the characters express their

ideas

in

distorted

non-standard

French/English imbedded in indigenous

speech and thinking, likely to be

unrecognisable to those who are strange to

that background. As Okara (1973, p.137-138)

posits, these African ideas, philosophy,

folklore and imagery (which abound in the

works of Achebe, Oyono, and Ngugi) help to

keep as close as possible to vernacular

expressions, and thus adequately express

African ideas and thoughts. And this is the

crux of the matter!

6. Discussion of the Findings

A major problem faced by translators is

how to deal with cultural specificity, given

that translation is generally viewed both as an

act of interlingual communication and as a

process of cultural transfer (Dayan Liu, 2012,

p. 39). Cultural and literary peculiarity is very

typical of Africa as seen above. In this light,

Okpewho (1992, p. 367) for instance states

that on the basis of fieldwork done in

Liberialiteracy has made no appreciable

difference in the modes of oral thinking in a

traditional [African] society.

The difficulties of translating cultural and

literary specificity have thus induced scholars

to propose two major approaches to

translating them, namely foreignisation

(source text-oriented) and domestication

(target text-oriented). Whereas, it is known

that the West, for instance employs both the

domestication and foreignisation macrostrategies (Morvkov, 1993; Ladouceur,

1995; Merino, 2000; Aaltonen, 1993 & 2000,

p. 4; Upton, 2000; Kruger, 2000; Espasa,

2000), justifying what Snell-Hornby (1988,

p. 112; 1995) calls situation of source text

and function of the translation, the African

translation province has tenaciously opted

for a clearly semantic, overt and "literal"

foreignising macro-strategy in which formal

equivalence takes priority over dynamic

equivalence (domestication).

6.1 The findings in translation scholarship

The following scholars uphold the

foreignising perspective for African cultural

and literary peculiarity.

Okpewho (1992, p. 182-294) opts for a

transcription of African creative writing that

strives to reproduce with a degree of

faithfulness.the

peculiar

circumstances, and wisely retain the

narrators exploitation of the geographical

setting of the place as well as the idiom of

the time, for the narrative text is the

product of the genius of the artist or artists

working within a particular context

(Okpewho, 1992, p. 300), else it will become

typically un-African and engender the

questioning of the authenticity of the

translation.

For Bandia (1993, p. 57), the translator of

African works, ought to "preserve the

original function of the source text in its

culture, as the translator of African works

is mainly concerned with preserving the

"situation of the source text". He (1993, p.

57) terms this a carry-over of African

sociolinguistic and sociocultural values into

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

Wanchia, T. N

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Page | 153

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

July-September, 2015

the European Language, and further

insistently states that

Translating African creative works is a

source-text oriented translation process in

which the target language, the European

language, is modified to accommodate the

African world-view. This process goes far

beyond merely substituting linguistic and

cultural equivalents. It is a negotiating

process in the sense that two divergent

sociocultural systems that are in contact

attempt to arrive at a happy solution in

expressing the African world-view in the

European language. This negotiating process

is made possible through translation

techniques such as calques, semantic and

collocational shifts (Bandia, 1993, p. 74).

ISSN:2308-5460

Still from the African province, Suh (2005,

p. 201) posits that African post-colonial

writers make a conscious attempt to sustain

an authentic African discourse, albeit in a

foreign language. It emanates from their own

cultural and intellectual background, passed

through the matrix of their own cultural

background. Suh (2008, p. 116-117) then

concludes that foreignisation is more suitable

for the translation of African creative writing.

Summer-Paulin (1995, p. 519-719) joins

African scholars like Ade Ojo (1986), and

Kourouma (as cited in Kon, 1992) to posit

that translators working with languages of

remote cultures such as African traditions

should preferably be source-text oriented

(literal translation) since that constitutes a

reflection of both a cultural system and social

organization of a specific community that

recreates a particular atmosphere and way of

thinking.

Finally, Berman (1985, p. 59, in Bandia,

1993, p. 57).) proposes "l'adhrence obstine

du sens sa lettre [obstinate adherence of

meaning to the letter], (my translation),

which allows translators of African literature,

for the most part, to

translate African thought literally into

European languages, since they understand

the significance of the rapport between

"sens" and "forme." As noted by Berman

(1985, p. 36), "littralit" is not necessarily

"mot mot," neither is it "calque." Literal

translation, as practised by translators of

African creative writing, is an example of

what Berman means when he asserts that

meaning and form are inseparable.

In all, the relationship between

translation quality and African cultural and

literary specificity is therefore bound to be

unusual, and calls for a sort of particularised

African

translation

perspective

that

challenges a blind and generalised

application of acquiesced frameworks. That

is why this article concludes with a pertinent

question.

7. Conclusion

From the above discussion, one is wont to

ask the question whose translation quality

then? This is appropriate because both

translation and translation quality are first

and foremost very volatile concepts. A few

scholars can be summoned to back this

opinion include House (1976, p. 64) who

opines that translation quality assessment

can never be completely objectified in the

manner of the results of natural science

subjects. In like manner, Pym (1998) asserts

that the scenario will continue to be

intriguing given that there is no perfect

translation or intended purpose (skopos).

Finally, Muzii (2006) states that even if

features and scope must be specified, the

attempt to strive for a single allencompassing

metric

is

not

only

troublesome, but can also be useless as a

simple metric would not reveal all problems.

Hence, the widespread concept of quality

assessment will continue to be a relative one

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 154

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

(due to many conflicting contextual

parameters, amongst which is culturespecificity) despite the laborious enterprise of

crafting and using metrics, rubrics and

models. In other words, there is, and will

continue to be incontestable translation

quality

assessment

provincialisation

/balkanisation, mindful of the strong and

growing concept of culture-specificity. That

makes it germane to make an apologia for a

cautious and contextualised application of

metrics, rubrics and models to translation

quality assessment,

References:

Aaltonen, S. (1993). Rewriting the Exotic: The

Manipulation of Otherness in Translated Drama.

In Catriona P. (ed.), Proceedings of XIII FIT

World Congress, 26-33. London, Institute of

Translation and Interpreting.

Aaltonen, S. (2000). Time-sharing on stage:

Drama translation in theatre and society.

Cleveland,

Buffalo,

Toronto,

Sydney:

Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Achebe, C. (1958/1994). Things Fall Apart.

New York. Anchor Books.

Ade Ojo, S. (1986). The role of the translator of

African written literature in intercultural

consciousness and relationships. Facets of

literary translation. Meta, XXI, 3. Canada: Les

Presses de lUniversit de Montral.

Adams, A. (trans), (1981). The suns of

Independence. By Ahmadou Kourouma. New

York: Holmes and Meier.

Akrobou, E.A. (2006). La traduction de la

culture et de loralit travers lcriture

romanesque de Kourouma, Francofona 15,

2006, 201-214. Universidad de Salamanca.

Akrobou, A. E. (2013). Traduire Kourouma

Ahmadou: Entre ambigit scripturale et

ambigit orale dans un processus de transfert

culturel, in Diandu Bi Kacou Parfait,

Approches

interculturelles

de

loeuvre

dAhmadou Kourouma, pp. 2536, Le Graal,

Montreuil.

Ali Darwish (1999). Translation Quality

Evaluation for the New Millennium, at-turjuman

online, 1999. Writescope Publishers. Melbourne.

Ali Darwish. (1999). Towards a theory of

constsraints in translation. Draft Version 0.2.

Ali Darwish. (2001). The Translator's Guide. Ali

Darwish. Writescope: Melbourne. 450 pp.

Al-Qinai, J. (2000). Translation quality

assessment:

strategies,

parameters,

and

procedures, Meta XLV:3, pp. 497-519.

Antonopoulou, E. (2002). A cognitive Approach

to literary humour Devices: Translating

Raymond Chandler. In Vandaele, J. (ed.),

Translating Humour. The Translator, Vol. 8,

Number 2 (2002), 149-172. United Kingdom:St.

Jerome.

Attardo, S. (1994). Linguistic Theories of

Humour. Berlin & New York: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 4,

[MUP], 1972).

Baker, M. (1992). In Other Words - A

Coursebook on Translation. London: Routlegde.

Baker (1998/2001), The Routledge Encyclopedia

of Translation Studies, 241-245. London:

Routledge.

Bandia, P. (1993). On Translating Pidgins and

Creoles in African Literature. Traduction,

Terminologie, Redaction 6-2, 94-114.

Bandia, P. (1993). Translation as Culture

Transfer: Evidence from African Creative

Writing, Traduction, Terminologie, Redaction

6-2, 55-78.

Bassnett, S. (1991). Translating for the theatre:

The case against performability. In TTR, Vol. 1,

No 4, 99-111.

Bassnett, S. (1980). Translation Studies, 14.

New York: Methuen & Co.

Bassnett, S. (1991). Translation studies. London:

Routlegde.

Bassnett, S. (1993). Comparative literature A

critical introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bassnett, S. (1998a). Still trapped in the

labyrinth: Further reflections on translation and

the theatre. In Bassnett S. and Lefevere A.

(eds.), 1998: 90-108.

Beaugrande, R. de. (1978). Factors in a theory

of poetic translating. Assen: van Gorcum.

Beeby, A. (2000). Teaching translation from

Spanish to English. Ottawa: University of Ottawa

Press.

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

Wanchia, T. N

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Page | 155

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Bell, R. (1987). Translation theory: where are we

going? In Meta 32, 4:403-415.

Berman. A. (1985b/2000). Translation and the

trials of the foreign, L. Venuti (trans.), La

traduction comme preuve de letranger, Texte

(1985):67-81), in L. Venuti (ed.) (2000).

Bjornson, R. (2002). Writing and popular

culture in Cameroon. In Newell, S. (ed.),

Readings in African popular fiction, 71-76.

London: The International African Institute.

Boase-Beier, J. & Holman, M. (eds.). (1998).

The practices of literary translation: Constraints

and creativity. United Kingdom: St. Jerome.

Brislin, R. (ed.). (1976). The Implication of

Culture on Translation Theory and Practice.

Translation: Applications and research, 47-92.

New York: Gardiner Press.

Catford, J. (1965). A Linguistic Theory of

Translation. London, Oxford UP,

Crystal, D. (1987). The Cambridge encyclopedia

of language. Cambridge, England: CUP.

Darah, G. G. (1982). Battles of songs: A case

study of satire in the Udje dance-songs of the

Urhobo of Nigeria. Ph.D thesis, Department of

English, University of Ibadan.

Dayan, L. (2012). Subtitling Cultural Specificity

from English to Chinese. American International

Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 2 No.10;

October 2012 pg 39. Chongqing Jiaotong

University.

Delabastita, D. (ed.). (1996). Introduction.

Wordplay and translation. The Translator. Vol. 2

Number 2, 1996. United Kingdom: St Jerome.

Espasa, E. (2000). Performability in translation:

Speakability? Playability? Or Saleability?. In

Upton, C-A. (ed.), Moving Target: translation

and cultural relocation. Manchester: St Jerome.

Evembe, F. (1988). Limportance de la

smantique dans la naissance dune pice de

thtre . In Butake, B. & Doho, G. (eds.),

Thtre Camerounais/ Cameroonian Theatre:

Actes du colloque de Yaound. Yaounde:

Cameroon: BET & Co (Pub) Ltd.

Farahzad, F. (1992). Testing achievement in

translation classes. In C. Dollerup & A.

Loddergard (Eds.), Teaching translation and

interpreting

(pp.

271-278)

Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Fofi, J. R. (2007). La cration linguistique

dramatique au Cameroun. Yaound Cameroun:

Presses Universitaires de Yaound.

Frawley, W. (ed.). (1984). In Search of the

Third Code: An Investigation of Norms in

Literary Translation. University of Delaware

Press; Associated University Presses.

Gerasimov, A. (2005). My golden rules for

quality assurance. Retrieved on March 20, 2015

from: http://fra.proz.com/doc/534.

Goff-Kfouri, C. A. (2005). Testing and

evaluation in the translation classroom.

Translation Journal, 9(2), 75-99.

Gyasi, K. (1999). Writing as Translation:

African Literature and the Challenges of

Translation. Research in African Literatures 302, 75-87.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Languages as social

semiotics: The social interpretation of language

and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Hatim, B. & Mason, I. (1994). Discourse and

the translator. London and New York: Longman.

Hatim, B. & Mason, I. (1997). The translator as

communicator. USA and Canada: Oxon.

Hatim, B. (2000). Teaching and Researching

Translation, Pearson Education Limited,

Edinburgh Gate, England.

Hatim, B. (1998/2001). "Discourse analysis and

translation" In: Baker M. (ed.), Routledge

Encyclopedia

of

Translation

Studies.

London/New York: Routledge.

Hewson, L. & Martin, J. (1991). Redefining

Translation:

the

Variational

Approach

London:Routledge.

Hickey, L. (ed.). (1998). The Pragmatics of

Translation.

(ed).

Clevedon:

Philadelphia:Multilingual. Matters, 242 pp.

House, J. (1976/1997). Translation quality

assessment: A model revisited. Niemeyer,

Tbingen House J. (1977). A Model for

Translation Quality Assessment. Tubingen:

Gunter Narr.

House J. (2012). "Translation Quality

Assessment: Linguistic Description versus Social

Evaluation". META, XLVI, 2, 2001.

ISO. (1994). ISO 8402:1994 Quality

management and quality assurance Vocabulary

International Organization for Standardization.

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 156

African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation Quality Debate

Jakobson, R. (1989). The Dominant,

Twentieth Century literary theory, 26-29.

Newton, K.M. (ed.). London: Macmillan

Education Ltd.

Kim, Y. Y. (1988). On theorizing intercultural

communication. In Kim Y. Y. & Gudykunst, W.

B.

(eds.),

Theories

in

intercultural

communication, 1-25. London and New Delhi:

Sage publications.

Khanmohammad , H. & Osanloo, M. (2009).

Moving toward Objective Scoring: A Rubric for

Translation Assessment. JELS, Vol. 1, No. 1, Fall

2009, 131-153. IAUCTB

Kon, A. (1992). Le romancier africain devant

la langue dcriture . Francophonia, 22:75-86.

Klimenko, S. (2004). In Babel, No. 50:30, 193214.

Kon, A. (1992). Le romancier africain devant

la langue dcriture . Francophonia, 22:75-86.

Kourouma, A. (1970). Les soleils des

indpendances. Paris:Edition du Seuil, Paris,

Laye, C (1953), LEnfant noir, Plon.

Kress G. (1985). Linguistic Processes in

Sociocultural Practice. Victoria, Deakin

University Press.

Kruger, A. (2000). Lexical Cohesion and

Register Variation in Translation: The

Merchant of Venice in Afrikaans.

Ladmiral , J. R. (1979). Traduire: thormes

pour la traduction, Paris: Payot.

Ladouceur, L. (1995). Normes, Fonctions et

Traduction Thtrale . Meta, XL, No I, 31-38.

Merino, R. (2000). Drama translation

Strategies: English-Spanish (1950-1990. Babel,

Vol. 46 No. 4, 357-365.

Meschonnic, H. (1973). Pour la Potique II,

Paris, Gallimard.

Morvkov A. (1993). Les problmes

spcifiques de la traduction des drames .

Proceedings of XIII FIT World Congress.

Institute of Translation and Interpreting, London,

34-37.

Muzii, L. (2006). Quality assessment and

economic sustainability of translation. Gruppo

L10N Roma.

Ndzana, M. H. (1988). Le thtre populaire

camerounais daujourdhui . In Butake, B. and

Doho.

G,

(eds.),

In

Cameroonian

Theatre/Thtre Camerounais, Actes du colloque

de Yaounde. Yaounde: Cameroon: BET & Co

(Pub) Ltd.

Ndzi, O. P. (1985). Identit culturelle

camerounaise

et

expression

thatrale

camerounaise , 339-359.

Newmark, P. (1981/1995). Approaches to

Translation. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Newmark, P. (1988). A Textbook of Translation.

London, Prentice-Hall.

Nida, E. (1964/1977). Toward a Science of

Tanslation with Special Reference to Principles

and Procedures Involves in Bible Translating :

Leiden : E. J. Brill.

Nida, E. (1982). Translating Meaning, 74. San

Dimas, California: English Language Institute.

Ngeng, M. (2015). Appraising Adrian Adams

translation of orality in Ahmadou Kouroumas

Les soleils des indpendances as The suns of

independence. Unpublished M.A Dissertation,

University of Buea.

Ngugi, W. T. (1965/1989). The River Between.

Heinemann. ISBN 0-435-90548-1.

Okara, G. (1973). The Voice. Fontana Modern

Novels.

Okpewho, I. (ed.). (1992). Towards a faithful

record: On transcribing and translating the oral

narrative performance. The oral performance in

Africa. Ibadan, Oweri, and Kaduna: Spectrum

Books Limited.

Okpewho, I. (1992). African oral Literature.

Bloomington/Indianapolis: Indiana University

Press.

Oyono, F. L. (1956). Le vieux ngre et la

mdaille. Editions Julliard.

Pavis, P. (1976). Problmes de smiologie

thtrale. Les Presses de lUniversitaire de

Qubec.

Pym, A. (1998). Method in Translation History.

Manchester: St. Jerome.

Reiss, K. (1971/1977/1989). Text types,

translation types and translation assessment,

translated by Chesterman A. In Venuti L. (ed.)

(2000), 160-171.

Riazi, A. M. (2003). The invisible in translation:

The role of text structure in translation. Journal

of Translation, 7, 1-8.

Robinson,

G.

(1988).

Cross-cultural

Understanding. Prentice, Hemel Hermpstead,

Hertfordshire.

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

Wanchia, T. N

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Page | 157

International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies

Volume: 03

Issue: 03

ISSN:2308-5460

July-September, 2015

Sainz, J. M. (1992). Student-centered correction

of translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John

Benjamins.

Saussure, Ferdinand de. (1916). "Cours de

Linguistique Gnrale (Course in General

Linguistics).

Schffner, C. (ed.) (1998). Translation and

Quality,

Clevedon/Philadelphia/

Toronto/Sydney/Johannesburg,

Multilingual

Matters.

Scott, W. S. (1962). Five Approaches to Literary

Criticism.

London:

Collier

Macmillan

Publishers.

Snell-Hornby, M. (1988/1995). Translation

Studies: An Intergrated Approach. Amsterdam

and Philadelphia, P.A.: John Benjamins.

Snell-Hornby, M. (1994). Translation studies, an

Interdiscipline. John Benjamins Publishing. 438

pp.

Steiner, G. (1992). After babel.

Oxford

University Press.

Suh, J. C. (2008). Drama Translation

Principles and Strategies. Epasa Moto, Vol. 3,

No 2. Cameroon: Agwecam.

Suh, J.C. (2005). The Appropriation of

European Languages in Cameroonian Literary

Works: Globalisation and the African

Experience:

Implications

for

language,

Literature and Education. Limbe, ANUCAM.

Summer-Paulin, C. (1995). Traduction et

Culture:

Quelques

Proverbes

Africains

Traduits , 519-719. Meta, Vol.40, No 4.

Montreal: Les Presses de lUniversit de

Montral.

Toury, G. (1978/2000). The nature and role of

norms in literary translation, in L. Venuti (ed.)

(2000), 198-211.

Toury, G. (1995). Descriptive Translation

Studies - And Beyond. Amsterdam &

Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Tweney, R. & Hoeman, H. (1976). Translation

and sign language. In R. Brislin (Ed.),

Translation: Applications and research (pp. 138161). New York: Gardner.

Upton, C-A. (ed.). (2000). Moving Target:

Theatre Translation and Cultural Relocation.

UK:Manchester, St Jerome.

Vakunta.

P.W. (2008). On Translating

Camfranglais and Other Camerounismes. Meta:

Vol. 53, No. 4, 942-947.

Varney

(2008).

Deconstruction

and

Translation: Positions, Pertinence and the

Empowerment of the Translator. Journal of

Language & Translation 9-1. Bologna

University.

Vandaele, J. (ed.) (2002). Introduction: (Re)constructing humour : meanings and means.

Translating Humour. Translating Humour. The

Translator, Vol. 8, No. 2 (2002), 149-172. United

Kingdom, St. Jerome.

Vermeer, H. (1989/2000). Skopos and

commission in translational action. In L. Venuti

(ed.), (2000), 221-232.

Venuti, L. (1995). Translation Authorship,

Copyright, The Translator I (I):1-24.

Venuti, L. (1995a). The Translators Invisibility:

A History of Translation. London and New York:

Routledge.

Vinay, J-P. & Darbelnet, J. (1958). Stylistique

compare du franais et de langlais. Mthode de

traduction. Paris: Didier.

Vinay, J-P. & Darbelnet, J. (1959/1995).

Stylistique compare du franais et de langlais.

Mthode de traduction. In Vinay, J-P. &

Darbelnet, J (trans., 1958 version by Sager J. C.

and Marie-Jose H.), Comparative stylistics of

French and English: A methodology for

translation. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John

Benjamins.

Waddington, C. (2001). Different methods of

evaluating student translation: The question of

validity. Meta, 46(2), 311-325.

Wanchia, T. N. (2013). Investigating the latent

resistance of African creative popular art to

translation. African Journal of Social Sciences.

Vol. 4 No.2, Cameroon.

Wilss, W. (1974/82).

The Science of

Translation: Problems and Methods, Turbingen:

Narr.

Wilss, W. (1982). The Science of Translation:

Problems and Methods, Turbingen: Narr.

Zlateva, P. (ed. and Trans.). (1993). Translation

as social action. Russian and Bulgarian

Perspectives. Translation Studies Series. London

and New York. 132 pp.

Cite this article as: Wanchia, T. N. (2015). African Cultural and Literary Specificity in the Broad Translation

Quality Debate. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies. 3(3), 143-158. Retrieved from

http://www.eltsjournal.org

Page | 158

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Beyond the Political Spider: Critical Issues in African HumanitiesDe la EverandBeyond the Political Spider: Critical Issues in African HumanitiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translation As Culture Transfer, African WritingDocument25 paginiTranslation As Culture Transfer, African WritingEmily ButlerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asika Discourse Techniques in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall A1Document18 paginiAsika Discourse Techniques in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall A1wakoaisha2Încă nu există evaluări

- Conservation of Arabic ManuscriptsDocument46 paginiConservation of Arabic ManuscriptsDr. M. A. UmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translating Culture-Specific Items in Shazdeh EhteDocument14 paginiTranslating Culture-Specific Items in Shazdeh EhtesarahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why and How The Translator Constantly Makes Decisions About Cultural MeaningDocument8 paginiWhy and How The Translator Constantly Makes Decisions About Cultural MeaningGlittering FlowerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter Writing in Gikuyu Ngugi Wa ThionDocument26 paginiChapter Writing in Gikuyu Ngugi Wa Thionkihelland100% (1)

- An Approach To Domestication and ForeignizationDocument5 paginiAn Approach To Domestication and ForeignizationFrau YahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acts of Translation (Mieke Bal and Joanne Morra)Document8 paginiActs of Translation (Mieke Bal and Joanne Morra)billypilgrim_sfeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridging The Gap Between Translation and Culture Towards A 3jtlt68r0hDocument13 paginiBridging The Gap Between Translation and Culture Towards A 3jtlt68r0hEsra MohammedÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cultural Other, Interculture and Interculturality in Postcolonial Translation Dialogic-CommunicationDocument24 paginiThe Cultural Other, Interculture and Interculturality in Postcolonial Translation Dialogic-CommunicationKaffo Opeyemi AbiolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use of Culture-Laden Texts To Enhance Culture-Specific Translation Skills From English Into ArabicDocument19 paginiUse of Culture-Laden Texts To Enhance Culture-Specific Translation Skills From English Into ArabicMuhammedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translation and Postcolonial IdentityDocument20 paginiTranslation and Postcolonial IdentityannacvianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multilingual Practices Critical LiteraciDocument11 paginiMultilingual Practices Critical LiteraciamirrayamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Movie Title 1Document6 paginiMovie Title 1Dõng ĐinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language in Modern African DramaDocument10 paginiLanguage in Modern African DramaCaleb JoshuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1925-Article Text-3464-1-10-20210923Document17 pagini1925-Article Text-3464-1-10-20210923belayneh tadesseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural ApproachesDocument5 paginiCultural ApproachesOla HamadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translation Strategies of Culture Specific Items: A Case Study of " Dayee Jan Napoleon"Document25 paginiTranslation Strategies of Culture Specific Items: A Case Study of " Dayee Jan Napoleon"empratis86% (7)

- 1539 4229 1 SM PDFDocument20 pagini1539 4229 1 SM PDFDiệp Nguyễn Thị NgọcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wiley, National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations The Modern Language JournalDocument3 paginiWiley, National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations The Modern Language JournaldevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kwaku A. Gyasi, The African Writer As TranslatorDocument17 paginiKwaku A. Gyasi, The African Writer As TranslatorGhe CriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper 1Document29 paginiPaper 1Hopeful Li'le MissieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural and Linguistic Constraints Non Equivalence and Loss of Meanings in Poetry Translation An Analysis of Faiz Ahmed Faiz S PoetryDocument14 paginiCultural and Linguistic Constraints Non Equivalence and Loss of Meanings in Poetry Translation An Analysis of Faiz Ahmed Faiz S PoetryMohammad rahmatullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fayemi 2013 The Problem of Language in Contemporary African Philosophy Some CommentsDocument11 paginiFayemi 2013 The Problem of Language in Contemporary African Philosophy Some CommentsThabiso EdwardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translation NotesDocument29 paginiTranslation NotesPOOJA B PRADEEPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Misrepresentation Through TransDocument18 paginiCultural Misrepresentation Through TransText VideoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultures Languages International ConferenceI-134-140Document8 paginiCultures Languages International ConferenceI-134-140Sana' JarrarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translating Cultures. Translating Iran. Domestication and ForeignizationDocument14 paginiTranslating Cultures. Translating Iran. Domestication and Foreignizationmiss_barbarona100% (2)

- Minor Literature and The Translation of The M OtherDocument19 paginiMinor Literature and The Translation of The M OtherkamlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- African Litechapter 1Document3 paginiAfrican Litechapter 1Milkiyas BirhanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Translation and InterculturalityDocument4 paginiLiterary Translation and InterculturalityIJELS Research JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- As You Like It Translation ClassDocument16 paginiAs You Like It Translation ClassozkisaipekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Afrophone Philosophy ReflexionDocument24 paginiAfrophone Philosophy Reflexionajibade ademolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challenges of Translating Islamic Religious Items From Arabic Into EnglishDocument19 paginiChallenges of Translating Islamic Religious Items From Arabic Into EnglishSaber Salem100% (3)

- Bringing The News Back Home Strategies of Acculturation and ForeignisationDocument12 paginiBringing The News Back Home Strategies of Acculturation and ForeignisationWillem KuypersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orality and LiteracyDocument22 paginiOrality and LiteracyyaktaguyÎncă nu există evaluări

- African Languages and African LiteratureDocument14 paginiAfrican Languages and African LiteratureDESMOND EZIEKEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Style in Literary TranslationDocument13 paginiStyle in Literary TranslationIrman FatoniiÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Historical Overview On The Consideration of Literary Translation From A Comparative Literature Point of View - AIETIDocument16 paginiA Historical Overview On The Consideration of Literary Translation From A Comparative Literature Point of View - AIETIlucia barrullÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nadia Smaihi1Document16 paginiNadia Smaihi1Munther asadÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Moment of Truth in Translating Proper Names in Naguib Mahfouz' TrilogyDocument5 paginiA Moment of Truth in Translating Proper Names in Naguib Mahfouz' TrilogyShaymaa Salah ElkhoulyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11195-Article Text-22129-1-10-20220702Document12 pagini11195-Article Text-22129-1-10-20220702netflix2nd.xyzÎncă nu există evaluări

- African Languages and African Literature: UJAH Unizik Journal of Arts and Humanities November 2011Document15 paginiAfrican Languages and African Literature: UJAH Unizik Journal of Arts and Humanities November 2011William HugoÎncă nu există evaluări

- M&P Final Essay (Corrected)Document17 paginiM&P Final Essay (Corrected)minaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 16 Khalid PDFDocument8 pagini16 Khalid PDFamani mahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mustaphajellfeb 2015Document10 paginiMustaphajellfeb 2015Abdi ShukuruÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012A - Cultural Approaches To TranslationDocument7 pagini2012A - Cultural Approaches To TranslationDavid KatanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture - Specific Items and Literary Translation: Ilda PoshiDocument5 paginiCulture - Specific Items and Literary Translation: Ilda PoshiLarbi NadiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Products and DesignDocument6 paginiProducts and DesignBeatrixjill Ortiz DumadaugÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translation Studies and The Translation of The Holy Qur'AnDocument7 paginiTranslation Studies and The Translation of The Holy Qur'AnNoreddine HaniniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Terjemah Al-Qur'an Untuk Luar Atau DomestikDocument16 paginiTerjemah Al-Qur'an Untuk Luar Atau Domestikwahyudi salmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perspectives On InterpretingDocument14 paginiPerspectives On InterpretingMansour altobiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Durdureanu IrinaDocument13 paginiDurdureanu IrinaIrinel DomentiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ugo's WorkDocument52 paginiUgo's WorkStephen GeorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creative Translation in Theory and PracticeDocument4 paginiCreative Translation in Theory and PracticeshahadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Translation 1Document14 paginiLiterary Translation 1Hopeful Li'le MissieÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Global TurnDocument6 paginiThe Global TurnbrianÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study of Translators' Approach in Dealing With Culture-Specific Items in Translation of Children's Fantasy FictionDocument8 paginiA Study of Translators' Approach in Dealing With Culture-Specific Items in Translation of Children's Fantasy FictionPatrivsky RodríguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Folklore, Cohesion, and Meaning in Ojaide's AgbogidiDocument8 paginiFolklore, Cohesion, and Meaning in Ojaide's AgbogidiEMMANUEL EMAMAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysing John Evans Atta Mills' Speeches Projecting Him As A Man of Peace'Document6 paginiAnalysing John Evans Atta Mills' Speeches Projecting Him As A Man of Peace'IJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Input Flooding Via Extensive Reading in Iranian Field Dependent vs. Field Independent EFL Learners' Vocabulary LearningDocument13 paginiThe Role of Input Flooding Via Extensive Reading in Iranian Field Dependent vs. Field Independent EFL Learners' Vocabulary LearningIJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study of The Phenomenon of Pronominalization in DangmeDocument11 paginiA Study of The Phenomenon of Pronominalization in DangmeIJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Positioning Strategies in Iranian vs. Western Media Discourse: A Comparative Study of Editorials On Syria CrisisDocument11 paginiPositioning Strategies in Iranian vs. Western Media Discourse: A Comparative Study of Editorials On Syria CrisisIJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Confirmation From A Journalist: A Case Study of Azadeh Moaveni S Orientalist Discourse in Lipstick Jihad and Honeymoon in TehranDocument12 paginiConfirmation From A Journalist: A Case Study of Azadeh Moaveni S Orientalist Discourse in Lipstick Jihad and Honeymoon in TehranIJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subalternity in The Pearl That Broke Its Shell: An Alternative Feminist AnalysisDocument14 paginiSubalternity in The Pearl That Broke Its Shell: An Alternative Feminist AnalysisIJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Short Stories of F. Sionil Jose Using Marxism As A Literary VistaDocument11 paginiReading Short Stories of F. Sionil Jose Using Marxism As A Literary VistaIJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Panopticism, Power-Knowledge and Subjectivation in Aboutorab Khosravi's The Books of ScribesDocument14 paginiPanopticism, Power-Knowledge and Subjectivation in Aboutorab Khosravi's The Books of ScribesIJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Translation Quality Assessment of Two English Translations of Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam Based On Juliane House's Model (1997)Document10 paginiA Translation Quality Assessment of Two English Translations of Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam Based On Juliane House's Model (1997)IJ-ELTSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Các chỉ số ảnh hưởng chỉ số môi trường đầu tưDocument13 paginiCác chỉ số ảnh hưởng chỉ số môi trường đầu tưK59 Nguyen Dang VuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personality Assessment Questionnaire (PAQ) : January 2016Document4 paginiPersonality Assessment Questionnaire (PAQ) : January 2016Shamsa KanwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Socio-Economic Determinants of HIV/AIDS Infection Rates in Lesotho, Malawi, Swaziland and ZimbabweDocument22 paginiThe Socio-Economic Determinants of HIV/AIDS Infection Rates in Lesotho, Malawi, Swaziland and Zimbabweecobalas7Încă nu există evaluări

- Pharmacoeconomics CompiledDocument53 paginiPharmacoeconomics CompiledMuhammad Ibtsam - PharmDÎncă nu există evaluări

- ch10 Acceptance Sampling PDFDocument29 paginich10 Acceptance Sampling PDFgtmani123Încă nu există evaluări

- Critique 1Document60 paginiCritique 1Fiona PinianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sales Skills AssessmentDocument5 paginiSales Skills Assessmentsinchanacr07Încă nu există evaluări

- Engineering Research Methodology Test #2 Part A: Question BankDocument2 paginiEngineering Research Methodology Test #2 Part A: Question BankrdsrajÎncă nu există evaluări

- TilesDocument58 paginiTilesRicky KhannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solution Manual For Managing, Controlling, and Improving Quality, 1st Edition, Douglas C. Montgomery, Cheryl L. Jennings Michele E. PfundDocument36 paginiSolution Manual For Managing, Controlling, and Improving Quality, 1st Edition, Douglas C. Montgomery, Cheryl L. Jennings Michele E. Pfundwakeningsandyc0x29100% (13)

- Entropy Optimization Principles and Their ApplicationsDocument18 paginiEntropy Optimization Principles and Their ApplicationsPabloMartinGechiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lean Six Sigma RoadmapDocument16 paginiLean Six Sigma RoadmapSteven Bonacorsi100% (11)

- It Thesis Title SystemDocument4 paginiIt Thesis Title Systemdnppn50e100% (2)