Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

06 - Sandstrom V Montana

Încărcat de

Rhett GaerlanTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

06 - Sandstrom V Montana

Încărcat de

Rhett GaerlanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

SANDSTROM v.

MONTANA

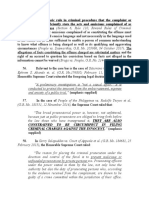

June 18, 1979 | Brennan, J. | Certiorari | Presumptions

PETITIONER: David Sandstrom

RESPONDENT: Supreme Court of Montana

SUMMARY: Sandstrom confessed to the killing of Annie Jessen, and was charged with deliberate homicide. His counsel argues

that since Sandstrom did not do it purposely or knowingly, he cannot be convicted of said crime. The trial court instructed the jury

that the law presumes that a person intends the ordinary consequences of his voluntary acts. Petitioner objected on the ground that

such presumption shifted the burden of proof on the defense. The Supreme Court held that such instruction was unconstitutional,

because regardless if the jury interpreted such instruction as permissive or mandatory, It cannot discount the possibility that the

jurors will actually proceed upon one or the other of those interpretations.

DOCTRINE: A state must prove every ingredient of an offense beyond a reasonable doubt, and . . . may not shift the burden of

proof to the defendant by means of such a presumption.

FACTS:

1. 18-year-old David Sandstrom confessed to the slaying of

Annie Jessen. He was charged with deliberate homicide, in

that he purposely or knowingly caused the death of Jessen.

2. At trial, Sandstroms counsel argued that his client did not

do so purposely or knowingly, and was therefore not guilty

of deliberate homicide, but of a lesser crime. This claim was

supported by the testimony of two court-appointed mental

health experts, which demonstrated that the killing was due to

a personality disorder aggravated by alcohol consumption.

3. The prosecution requested the trial judge to instruct the

jury that "the law presumes that a person intends the

ordinary consequences of his voluntary acts." Petitioner's

counsel objected, arguing that the instruction has the effect of

shifting the burden of proof on the issue of purpose or

knowledge to the defense, and that that is impermissible under

the Federal Constitution, due process of law.

4. The objection was overruled and the jury sentenced herein

petitioner to 100 years of prison.

5. Upon appeal to the Supreme Court of Montana, the latter

affirmed the Decision because the cases cited by defendant

(which prohibited shifting the burden of proof to the defendant

by means of a presumption) did not prohibit allocation of

some burden of proof.

ISSUE/S:

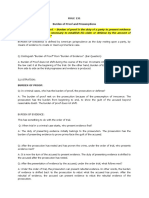

1. WON the judges instruction had the effect of relieving the

State of the burden of proof of petitioners state of mind

(and is therefore unconstutional) YES

RULING: The judgment of the Supreme Court of Montana is

reversed

RATIO:

1. Respondent argues that the instruction merely described a

permissive inference, but did not require the jury to draw

conclusions about a defendants intent from his actions.

2. But the Court held that, even respondent admits that it is

possible that the jury believed they were required to apply the

presumption. They were not told they had a choice, or that

they might infer such a conclusion; they were only told that

the law presumed it. A reasonable juror could easily have

viewed such an instruction as mandatory.

3. Respondent, in the alternative, argues that even if it was

viewed as a mandatory presumption, the presumption is not

conclusive and could be rebutted. The instruction required the

jury to find intent unless the defendant offered evidence to

the contrary. At most, it placed a burden of production but

did not shift to the accused the burden of persuasion.

Moreover, only the Supreme Court of Montana could have an

authoritative reading of the effect of the presumption.

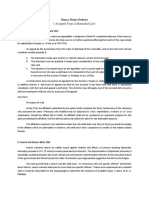

4. The Court held, however, that the SC of Montana is not the

final authority on the interpretation which a jury could have

given the instruction. A reasonable juror could well have been

misled by the instruction given, and could have believed that

the presumption was not limited to requiring the defendant to

satisfy only a burden of production. The jury was told that

the law presumes that a person intends the ordinary

consequences of his voluntary acts, and not that the

presumption could be rebutted by simple presentation of

some evidence.

5. A reasonable jury could have interpreted the presumption as

an irrebuttable direction by the Court to find intent once

convinced of the facts triggering the presumption.

Alternatively, the jury could interpret such as a direction to

find intent upon proof of the defendants voluntary actions

unless defendant proved the contrary by some quantum of

proof which may well have been greater than some

evidence, thus shifting the burden of persuasion.

6. We do not reject the possibility that some jurors may have

interpreted the challenged instruction as permissive, or, if

mandatory, as requiring only that the defendant come forward

with "some" evidence in rebuttal. However, the fact that a

reasonable juror could have given the presumption

conclusive or persuasion-shifting effect means that we

cannot discount the possibility that Sandstrom's jurors

actually did proceed upon one or the other of these latter

interpretations. And that means that, unless these kinds of

presumptions are constitutional, the instruction cannot be

adjudged valid.

7. Because David Sandstrom's jury may have interpreted the

judge's instruction as constituting either a burden-shifting

presumption like that in Mullaney or a conclusive presumption

like those in Morissette and United States Gypsum Co., and

because either interpretation would have deprived defendant

of his right to the due process of law, the Cour holds the

instruction given in this case unconstitutional.

8. The Court previously held that the Due Process Clause

protects the accused against conviction except upon proof

beyond a reasonable doubt of every fact necessary to

constitute the crime with which he is charged. Here, the

petitioner was charged with and convicted of deliberate

homicide, committed purposely or knowingly. It is clear that,

under Montana law, whether the crime was committed

purposely or knowingly is a fact necessary to constitute the

crime of deliberate homicide. Under either of the two possible

interpretations of the instruction set out above, precisely that

effect would result, and that the instruction therefore

represents constitutional error.

9. As to conclusive presumptions, Morissette v. US held:

"It follows that the trial court may not withdraw or prejudge

the issue by instruction that the law raises a presumption of

intent from an act A conclusive presumption which

testimony could not overthrow would effectively eliminate

intent as an ingredient of the offense. A presumption which

would permit, but not require, the jury to assume intent from

an isolated fact would prejudge a conclusion which the jury

should reach of its own volition. A presumption which would

permit the jury to make an assumption which all the evidence

considered together does not logically establish would give to

a proven fact an artificial and fictional effect. In either case,

this presumption would conflict with the overriding

presumption of innocence with which the law endows the

accused and which extends to every element of the crime."

(Other cases decided similarly were also cited by the Court)

10. A presumption which, although not conclusive, had the

effect of shifting the burden of persuasion to the defendant,

would have suffered from similar infirmities. If Sandstrom's

jury interpreted the presumption in that manner, it could have

concluded that, upon proof by the State of the slaying and of

additional facts not themselves establishing the element of

intent, the burden was shifted to the defendant to prove that he

lacked the requisite mental state. Such presumption was found

constitutionally deficient in Mullanet v. Wilbur.

11. In Patterson, the Court held: A state must prove every

ingredient of an offenst beyond a reasonable doubt, and

may not shift the burden of proof to the defendant by means of

such a presumption.

12. Because David Sandstrom's jury may have interpreted the

judge's instruction as constituting either a burden-shifting

presumption like that in Mullaney or a conclusive presumption

like those in Morissette and United States Gypsum Co., and

because either interpretation would have deprived defendant

of his right to the due process of law, we hold the instruction

given in this case unconstitutional.

13. Respondent argues, that even if the presumption is

unconstitutional, the petitioner may still be convicted. They

argue that since the word intends (as found in the judges

instruction) was not defined, the jurors could have interpreted

such word as referring only to the defendants purpose. Thus,

a jury which convicted Sandstrom solely for his "knowledge,"

and which interpreted "intends" as relevant only to "purpose",

would not have needed to rely upon the tainted presumption at

all. But the Court held that even if a jury could have ignored

the presumption and found defendant guilty because he acted

knowingly, we cannot be certain that this is what they did do.

As the jury's verdict was a general one, they would have no

way of knowing that Sandstrom was not convicted on the

basis of the unconstitutional instruction.

14. Finally, respondent argues that the instruction constituted

harmless error because the defendants confession and the

psychiatrists testimony demonstrated that Sandstrom

possessed the requisite mental state. However, the Court held

that the petitioner only confessed to the slaying, and not to his

mental state, and in any event, an unconstitutional jury

instruction on an element of the crime can never constitute

harmless error.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Sandstrom v. MontanaDocument1 paginăSandstrom v. MontanaTaco BelleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Murray L. Petersen v. United States, 268 F.2d 87, 10th Cir. (1959)Document6 paginiMurray L. Petersen v. United States, 268 F.2d 87, 10th Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module Consti2 FinalsDocument103 paginiModule Consti2 FinalsFunnyPearl Adal GajuneraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3.standard of ProofDocument29 pagini3.standard of ProofMeghan PaulÎncă nu există evaluări

- DPP V BoardmanDocument5 paginiDPP V BoardmanMERCY LAWÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jury NullificationDocument3 paginiJury Nullificationapi-173128026Încă nu există evaluări

- Rem Rev 2 Syllabus With DoctrinesDocument26 paginiRem Rev 2 Syllabus With DoctrinesFord Osip100% (1)

- Jay D. Scott v. Ohio, 480 U.S. 923 (1987)Document3 paginiJay D. Scott v. Ohio, 480 U.S. 923 (1987)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ralph Cecil Feltrop v. State of Missouri, 501 U.S. 1262 (1991)Document4 paginiRalph Cecil Feltrop v. State of Missouri, 501 U.S. 1262 (1991)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Juris. Probable Cause. PIDocument4 paginiJuris. Probable Cause. PISamJadeGadianeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Norman L. Longval v. Lawrence R. Meachum, 693 F.2d 236, 1st Cir. (1982)Document4 paginiNorman L. Longval v. Lawrence R. Meachum, 693 F.2d 236, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annette Louise Stebbing v. Maryland, 469 U.S. 900 (1984)Document9 paginiAnnette Louise Stebbing v. Maryland, 469 U.S. 900 (1984)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3rd Page Pt. 2Document71 pagini3rd Page Pt. 2sofiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burden and Standard of Proof Revision!Document3 paginiBurden and Standard of Proof Revision!JussMystyleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ralph Ben David v. Anthony P. Travisono, 495 F.2d 562, 1st Cir. (1974)Document4 paginiRalph Ben David v. Anthony P. Travisono, 495 F.2d 562, 1st Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robert D. Heiney v. Florida, 469 U.S. 920 (1984)Document4 paginiRobert D. Heiney v. Florida, 469 U.S. 920 (1984)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 124539-1998-Alonte v. Savellano Jr.Document48 pagini124539-1998-Alonte v. Savellano Jr.elma campoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Concerned Citizens v. Judge ElmaDocument3 pagini3 Concerned Citizens v. Judge ElmaryanmeinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Christopher A. Burger, Cross-Appellant v. Ralph Kemp, Warden, Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Center, Cross-Appellee, 785 F.2d 890, 11th Cir. (1986)Document9 paginiChristopher A. Burger, Cross-Appellant v. Ralph Kemp, Warden, Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Center, Cross-Appellee, 785 F.2d 890, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leroy Chasson v. Joseph Ponte, 459 U.S. 1162 (1983)Document4 paginiLeroy Chasson v. Joseph Ponte, 459 U.S. 1162 (1983)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magbanua vs. JunsayDocument20 paginiMagbanua vs. JunsayTrisha Paola TanganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: en BancDocument48 paginiPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: en BancJela SyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3.) Alonte - v. - Savellano - Jr.Document48 pagini3.) Alonte - v. - Savellano - Jr.Bernadette PedroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Probable CauseDocument11 paginiProbable Causerodan parrochaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ho Vs PeopleDocument3 paginiHo Vs Peoplemaricar bernardinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Cabral - 131909 - Synopsis - SyllabiDocument3 paginiPeople Vs Cabral - 131909 - Synopsis - SyllabiJune Canicosa HebrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law - Estafa Defense - Good Faith As A Defense in The Felony of EstafaDocument5 paginiLaw - Estafa Defense - Good Faith As A Defense in The Felony of EstafaNardz Andanan100% (4)

- Mia SLLS Evidence - Ivan SesayDocument14 paginiMia SLLS Evidence - Ivan SesayHyrich InspiresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal Procedure and Evidence Forecast 2018 BARDocument27 paginiCriminal Procedure and Evidence Forecast 2018 BARKin Pearly FloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- PDF TrialDocument91 paginiPDF TrialAliÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States Court of Appeals Third Circuit.: No. 17499. No. 17500Document5 paginiUnited States Court of Appeals Third Circuit.: No. 17499. No. 17500Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 131 EditedDocument20 pagini131 EditedGideon Salino Gasulas Buniel100% (1)

- 2016 Law On Evidence TSN - Third Exam (No Rules 133 and 134)Document36 pagini2016 Law On Evidence TSN - Third Exam (No Rules 133 and 134)Ronald ChiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robert Bumpus v. Frank Gunter, 635 F.2d 907, 1st Cir. (1980)Document11 paginiRobert Bumpus v. Frank Gunter, 635 F.2d 907, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crim Proc VillasisDocument32 paginiCrim Proc VillasisJane 96100% (1)

- Thomas F. McInerney v. Louis Berman and Francis X. Bellotti, 621 F.2d 20, 1st Cir. (1980)Document7 paginiThomas F. McInerney v. Louis Berman and Francis X. Bellotti, 621 F.2d 20, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law of Evidence CasesDocument37 paginiLaw of Evidence CasesGilbert KhondoweÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Douglas L. Oakes, 565 F.2d 170, 1st Cir. (1977)Document6 paginiUnited States v. Douglas L. Oakes, 565 F.2d 170, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anderson v. Butler, 23 F.3d 593, 1st Cir. (1994)Document12 paginiAnderson v. Butler, 23 F.3d 593, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- ConfessionDocument4 paginiConfessionOkin NawaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presumption - A Rule of Evidence - CorrectedDocument11 paginiPresumption - A Rule of Evidence - CorrectedArsh sharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- James J. Connor v. Philip J. Picard, 434 F.2d 673, 1st Cir. (1970)Document6 paginiJames J. Connor v. Philip J. Picard, 434 F.2d 673, 1st Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alonte Vs PeopleDocument54 paginiAlonte Vs PeopleCes YlayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurisprudence 2Document4 paginiJurisprudence 2KarlaAlexisAfableÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of Desistance, Not A Ground For DismissalDocument6 paginiAffidavit of Desistance, Not A Ground For DismissalRyan Acosta100% (1)

- Crimpro S3Document35 paginiCrimpro S3Kim Muzika PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bruno A. Koehler and Hugo W. Ackermann v. United States, 342 U.S. 852 (1951)Document3 paginiBruno A. Koehler and Hugo W. Ackermann v. United States, 342 U.S. 852 (1951)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 124539-1998-Alonte v. Savellano Jr.Document49 pagini124539-1998-Alonte v. Savellano Jr.Monique Allen LoriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 - Sanvicente vs. PeopleDocument16 pagini6 - Sanvicente vs. PeopleFbarrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Pine, Frank, III, 609 F.2d 106, 3rd Cir. (1979)Document4 paginiUnited States v. Pine, Frank, III, 609 F.2d 106, 3rd Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stacey Remedial Law Bar NotesDocument4 paginiStacey Remedial Law Bar NotesAiza CabenianÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Farina, 184 F.2d 18, 2d Cir. (1950)Document10 paginiUnited States v. Farina, 184 F.2d 18, 2d Cir. (1950)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Circumstantial EvidenceDocument12 paginiCircumstantial EvidenceAbhishek SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal Procedure AssignDocument4 paginiCriminal Procedure AssignMr WowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alonte vs. Savellano (G.R. No. 131652, March 9, 1998)Document54 paginiAlonte vs. Savellano (G.R. No. 131652, March 9, 1998)AndresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retracted ConfessionDocument11 paginiRetracted ConfessionMohd YasinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1965)Document5 paginiGiaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1965)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. LarranagaDocument29 paginiPeople vs. LarranagapauÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sanchez v. DemetriouDocument19 paginiSanchez v. Demetriouyanyan yuÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeDe la EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. Versoza PDFDocument1 paginăPeople v. Versoza PDFRhett Gaerlan100% (1)

- Malong v. PNRDocument3 paginiMalong v. PNRRhett GaerlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Aeronautics Administration vs. CADocument1 paginăCivil Aeronautics Administration vs. CARhett GaerlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- DIGEST-Sinaca vs. MulaDocument1 paginăDIGEST-Sinaca vs. MulaRhett Gaerlan100% (3)

- Jaramilla Vs COMELECDocument1 paginăJaramilla Vs COMELECRhett GaerlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Batongbacal LEGHISDocument2 paginiBatongbacal LEGHISRhett GaerlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- MLAExercisesDocument2 paginiMLAExercisesmissariadneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fam FrontDocument1 paginăFam FrontRhett GaerlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kord All of MeDocument2 paginiKord All of MeMuhammad Nuh IzzuddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chem 1 Lt2 Results 2-19-11Document2 paginiChem 1 Lt2 Results 2-19-11Rhett GaerlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art Appreciation: Learning OutcomesDocument13 paginiArt Appreciation: Learning OutcomesJohn Vincent EstoceÎncă nu există evaluări

- PDFDocument71 paginiPDFAnh LêÎncă nu există evaluări

- Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (Utar) : Faculty of Accountancy and Management (Fam)Document12 paginiUniversiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (Utar) : Faculty of Accountancy and Management (Fam)Wanqi LooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Municipal Summary Monitoring of Incidence On Violence Against Children (Vac) During The Covid-19 PandemicDocument2 paginiMunicipal Summary Monitoring of Incidence On Violence Against Children (Vac) During The Covid-19 PandemicDann MarrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liberty University BUSI 240 Quiz 4Document13 paginiLiberty University BUSI 240 Quiz 4Arshad HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- McLuhan - City As Classroom 2 PDFDocument185 paginiMcLuhan - City As Classroom 2 PDFcharlesnicholasconwayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recruitment Sele HRMDocument46 paginiRecruitment Sele HRMShweta HegdeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Berger J - Ways of Seeing, BBC and Penguin Books 1972Document79 paginiBerger J - Ways of Seeing, BBC and Penguin Books 1972Yao DajuinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self Respect MovementDocument2 paginiSelf Respect MovementJananee RajagopalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Getting The Call From Stockholm: My Karolinska Institutet ExperienceDocument31 paginiGetting The Call From Stockholm: My Karolinska Institutet ExperienceucsfmededÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agricultural Literacy: Clarifying A Vision For Practical ApplicationDocument15 paginiAgricultural Literacy: Clarifying A Vision For Practical ApplicationSubba RajuÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Conditions of Contract For Construction Works - 2004 & 2010 ClausesDocument18 paginiGeneral Conditions of Contract For Construction Works - 2004 & 2010 ClausesPaul Maposa40% (5)

- Bachelor of Engineering IN Civil Engineering: Visvesvaraya Technological University Jnana Sangama, BelagaviDocument3 paginiBachelor of Engineering IN Civil Engineering: Visvesvaraya Technological University Jnana Sangama, Belagavianon_591012339Încă nu există evaluări

- Project Platinum - Charge ListDocument5 paginiProject Platinum - Charge ListCityNewsTorontoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management CommunicationDocument244 paginiManagement CommunicationNikitha CorreyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 5 q2 Mathematics LasDocument102 paginiGrade 5 q2 Mathematics LasJohn Walter B. RonquilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- ISMS Control of Outsourced ProcessesDocument3 paginiISMS Control of Outsourced ProcessesAmine RachedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giải Chi Tiết Sách Từ Vựng Thày Vĩnh BáDocument4 paginiGiải Chi Tiết Sách Từ Vựng Thày Vĩnh BádèhyhygfÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPBUS SYLLABUSDocument10 paginiSPBUS SYLLABUSMark FaderguyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elizabeth Holmes Body Language ReportDocument6 paginiElizabeth Holmes Body Language ReportAmmajan75% (4)

- Assissting AmbulationDocument1 paginăAssissting AmbulationDrian Pot PotÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Monolingual and Bilingual Dictionary On The Foreign Language Learners' AcquisitionDocument4 paginiThe Effect of Monolingual and Bilingual Dictionary On The Foreign Language Learners' AcquisitionLong NguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matthew Lesko Let Uncle Sam Pay Your Bills PDFDocument33 paginiMatthew Lesko Let Uncle Sam Pay Your Bills PDFCarol100% (4)

- Environmental Analysis of Top Glove V2Document20 paginiEnvironmental Analysis of Top Glove V2Wan Khaidir100% (1)

- ESSAYDocument1 paginăESSAYRachellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excerpt of "Identity: The Demand For Dignity and The Politics of Resentment"Document5 paginiExcerpt of "Identity: The Demand For Dignity and The Politics of Resentment"wamu885100% (1)

- CAO - IRI Part - MDocument102 paginiCAO - IRI Part - MDariush ShÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math Masters PortfolioDocument5 paginiMath Masters Portfolioapi-340744077Încă nu există evaluări

- TechnopreneurshipDocument21 paginiTechnopreneurshipeun mun kangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proposal For Custom Clearance FOR ENERGAS LNG TERMINALDocument8 paginiProposal For Custom Clearance FOR ENERGAS LNG TERMINALAsadÎncă nu există evaluări