Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

China's IPO & Equity Market PDF

Încărcat de

tanyaa90Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

China's IPO & Equity Market PDF

Încărcat de

tanyaa90Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

FRBSF ECONOMIC LETTER

2016-18

June 6, 2016

Pacific Basin Note

Chinas IPO Activity and Equity Market Volatility

BY

FRANK PACKER AND MARK SPIEGEL

China has recently considered reforming its regulation of initial public offerings in equity

markets. Current policy allows more IPOs in rising markets but restricts new issues in falling

markets, possibly to avoid pushing down values of existing stocks. However, recent research

finds Chinas IPO activity has no effect on stock price changes, perhaps because of the low

volume relative to the overall market. As such, cyclical restrictions on IPOs do not appear to

have stabilized Chinese markets, so policy reforms may improve market efficiency without

increasing volatility.

Chinas financial depth is roughly in line with international norms based on GDP per capita (see

Eichengreen 2015). Yet much of the countrys financial activity remains focused on debt, particularly bank

loans. Despite impressive growth, its equity market is still small relative to the overall financial sector. As

such, a major policy goal for the country has been continued development of its equity markets.

While many companies already have entered equity markets, Chinas goal of moving further away from

the debt market and bank finance will require new firms to enter the stock market. However, initial public

offerings (IPOs) are controlled by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). The commission

has intermittently halted IPOs to stabilize stock markets (Figure 1). The most recent ban was from June to

November 2015, in the wake of the

Figure 1

steep equity market declines in China.

Number of IPOs and index values, Shanghai and Shenzhen

Index

Number of IPOs

60

In this Economic Letter, we examine

8500

the patterns of Chinese IPO activity.

7500

Our results confirm that IPO volume in

China follows hot and cold cycles

6500

similar to those observed globally: New

Number of IPOs

(right scale)

IPOs increase after periods of equity

5500

market appreciation and fall off after

share prices decline. If higher IPO

4500

activity resulted in overall stock market

gains, for example by absorbing funds

3500

that would otherwise be invested in

Value of indexes (left)

existing equity, then we would expect

2500

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

IPO volume to be inversely correlated

Source: World Federation of Exchanges, Bloomberg.

with equity price movements.

However, we find no such correlation.

Thus, there is little evidence that the historical practice of encouraging IPOs in hot markets and

discouraging them in cold markets has stabilized Chinese equity values.

50

40

30

20

10

2016

FRBSF Economic Letter 2016-18

June 6, 2016

The Chinese system for IPOs

Problems of asymmetric information, when a companys managers know much more about its prospects

than potential buyers, commonly arise in IPOs and the issuance of equities more generally. Such

information asymmetries can explain variation over time in equity volume in advanced economy markets,

since businesses can delay issuing equity when they know markets are undervalued and wait for a bull

market (see, for example, Lucas and MacDonald 1990).

Information asymmetries may be more serious in China, because of inadequate disclosure and

transparency. Zhou and Li (2016) document that one-third of the 600-plus small and medium companies

approved for IPOs between 2005 and 2014 experienced a drop in net income growth of more than 20%

after their first IPO. Of the sample, the study found that 29% had falsified their prospectuses before going

public. Stricter guidelines for IPOs from the CSRC in 2013 called for real, accurate, and complete

disclosure to satisfy basic legal criteria (Kreab & Gavin Anderson 2014).

Applications for IPOs must go through CSRCs Public Offering Review Committee for approval. This can

result in a massive backlog of firms awaiting approval; there are currently about 800 companies that have

applied for listing. The government gate-keeping role has also been associated with larger and stateowned firms that have superior government connections being more likely to obtain IPO approval.

Once an IPO is approved, offer prices are in principle set by a two-round book-building system,

introduced in 2005, in which mostly institutional investors are solicited for bids of interest. Retail

investors then apply for shares at a fixed price. Before this reform, prices were fixed at arbitrarily low

price-earnings ratios; together with the backlog of firms and lag times between the offer and the listing,

this generally resulted in prices well below what the market was willing to pay for the shares (Ritter 2011).

Though initial returns on IPOs in China were greatly reduced by the reforms, Song, Tan, and Yi (2014)

found that they still averaged 66% between 2006 and 2011, well over international norms.

How has the timing of IPO activity been managed?

Chinese authorities frequently suspend IPO market activity, and in fact have done so five times since

2005. The most recent cessations have occurred in the wake of market declines, and IPOs were able to

resume only after prices stabilized. IPOs were last halted in July 2015 during the downturn in Chinese

equity markets. IPOs were restarted in November 2015, and have continued to date despite renewed

volatility in Chinese equity markets this year.

The CSRC appears to have calibrated the pace of Chinese IPO activity in response to market movements.

The number of IPOs allowed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges typically moves closely with equity

values, as shown in Figure 1. One notable exception is in January 2014, when exchanges were opened to a

large volume of IPOs to ease the sizable backlog after a long prohibition period. More systematically, even

excluding months with no IPOs, the levels of initial offerings are closely related to past market returns:

There is a positive correlation between the total number of IPOs on the Shanghai and Shenzhen equity

markets and the previous three months returns in equity values (see Figure 2). Formal univariate

regression analysis demonstrates a statistically significant relationship. Our point estimate indicates that

a one-standard-deviation increase in equity returns over the previous three months is associated with

approximately five additional IPOs. Formal results are available in an online Appendix,

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2016/june/China-initial-publicofferings-and-market-volatility/el2016-18-appendix.pdf.

2

FRBSF Economic Letter 2016-18

Even in markets without strong

regulatory intervention, this pattern of

IPOs increasing in periods of high

market returns and declining when

markets go cold has long been

documented (see, for example,

Helwege and Liang 2004 and Hamao,

Packer, and Ritter 2000). Reports

suggest that selected companies with

preapproved IPOs have also been asked

to hold off on issuance (Sweeney and

Jianxin 2014).

Does IPO volume affect the

overall market?

June 6, 2016

Figure 2

Relationship between IPOs and 3-month average index growth

Number of IPOs

60

50

40

30

Fitted values

20

10

0

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

Index growth

0.4

0.6

Reducing market volatility appears to

be one motivation for the CSRC to regulate IPO activity. Media briefings after the July 2015 suspension

indicate that the action was taken to stabilize volatile stock markets (Zhu 2015). The timing patterns we

observe in China would be stabilizing in the short run if the supply of IPOs could affect the prices of other

shares, that is, if allowing more new issuance would cool excessively hot markets and restricting issuance

would warm up cold ones.

Evidence in some other markets suggests that IPOs can affect asset prices. Braun and Larrain (2009)

demonstrate that IPOs in 22 emerging markets push down the relative values of asset portfolios that

covary with the newly issued asset. These findings suggest that investors treat IPOs to some extent as

substitutes for equities that have already been issued and they can therefore push down the valuation of

those shares.

However, these effects are important only when the issuance is large relative to the size of the market

under study. This is unlikely to be the case in China, where the overall size of IPO issuance is quite small

relative to total capitalized market values. Even during the 2015 IPO boom, issuance in any month was, at

most, 0.06% of total Shanghai and 0.14% of Shenzhen market capitalized values. By comparison, the

average single IPO in the sample of Braun and Larrain represented 0.25% of market capitalization. While

market capitalization may greatly overstate the value of traded shares in some countries, the tradable

share in China is large. For example, at the end of June 2015, the tradable share of market capitalization

was 87% in Shanghai markets and 72% in Shenzhen markets.

Given the small size of IPO activity relative to overall market capitalization, it is then not too surprising

that the data show little correlation between the volume of IPOs and contemporaneous market

movements. Figure 3 plots the number of IPOs on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets combined against

average weighted returns of the indexes in these markets in the IPO month. There is clearly no strong

relationship between these series. We again confirm this empirically using univariate regression analysis,

available in our online Appendix. We find no statistically significant relationship between IPO activity and

contemporaneous equity market returns. For the special case in which IPO activity is halted altogether,

average monthly returns are actually higher on average than they are during months with positive

activity; again, this fails to indicate that managing IPO activity smooths market returns.

FRBSF Economic Letter 2016-18

One potential concern is that IPO

activity is endogenous, as our analysis

demonstrates that more takes place in

rising markets. If asset price

movements are persistent, then our

lack of observed correlation may

simply reflect CSRC policy.

Conclusion

June 6, 2016

Figure 3

Relationship between IPOs and concurrent index growth

Number of IPOs

60

50

40

30

Equity markets around the world

20

Fitted values

exhibit common patterns of IPO

activity, with activity increasing in

10

rising equity markets and falling in

0

cold ones. However, in most advanced

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

markets, this pattern stems from

Index growth

businesses timing their issuance

strategically to improve returns to existing shareholders. In contrast, the control over the timing of IPOs

by Chinas regulatory commission and the backlog of firms awaiting IPOs imply that the quantity of IPO

issuance in China has more than likely been a policy choice. Market stability has been one of the stated

objectives of Chinas IPO policy.

Timing IPO volume this way might be consistent with stabilizing Chinese asset values if IPOs were

pushing down the values of existing shares. However, IPO activity in China is quite small relative to the

overall capitalization of Chinas stock markets. As such, we would not expect much impact from its

management on Chinese equity values. Indeed, the analysis in this Letter finds almost no relationship

between IPO volume and equity price movements. We therefore find no evidence that the regimes

regulatory intervention has stabilized markets. Further, if China were to reform its IPO regulatory

practices, our analysis suggests that it should not cause the overall market to become less stable.

Frank Packer is a regional adviser in the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for

International Settlements.

Mark Spiegel is a vice president in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of

San Francisco.

References

Braun, Matias, and Borja Larrain. 2009. Do IPOs Affect the Prices of Other Stocks? Evidence from Emerging

Markets. Review of Financial Studies 22(4), pp. 1,5051,544.

Eichengreen, Barry. 2015. Financial Developments in Asia: The Role of Policy and Institutions, with Special

Reference to China. Paper prepared for Asian Monetary Policy Forum, Singapore.

http://abfer.org/docs/2015/financial-development-in-asia-the-role-of-policy-and-institutions-with-specialreference-to-china.pdf

Hamao, Yasushi, Frank Packer, and Jay Ritter. 2000. Institutional Affiliation and the Role of Venture Capital:

Evidence from Initial Public Offerings in Japan. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 8(5, October), pp. 529558.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927538X00000263

Helwege, Jean, and Nellie Liang. 2004. Initial Public Offerings in Hot and Cold Markets. Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis 39(3), pp. 541569.

FRBSF Economic Letter 2016-18

June 6, 2016

Kreab & Gavin Anderson. 2014. Chinas IPO Reboot and the CSRC. White paper, February.

http://www.kreab.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2014/01/Chinas-IPO-Reboot-and-the-CSRC-KreabGavin-Anderson.pdf

Lucas, Deborah, and Robert McDonald. 1990. Equity Issues and Stock Price Dynamics. Journal of Finance 45,

pp. 1,0191,043.

Ritter, Jay R. 2011. Equilibrium in the Initial Public Offerings Market. American Review of Financial Economics

3, pp. 347374.

Song, Shunlin, JinSong Tan, and Yang Yi. 2014. IPO Initial Returns in China: Underpricing or Overvaluation?

China Journal of Accounting Research 7(1), pp. 3149.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1755309113000531

Sweeney, Pete, and Lu Jianxin. 2014. Wave of China IPO Suspensions in Setback for Reforms. Reuters, January

13. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-ipos-idUSBREA0B0MS20140113

Zhou, Hong, and Guoping Li. 2016. Political Connections: An Explanation for the Consistently Poor Performance

of Chinas Stock Markets. ValueWalk online, January 20. http://www.valuewalk.com/2016/01/politicalconnections-an-explanation-for-the-consistently-poor-performance-of-china-stock-markets/

Zhu, Julie. 2015. Chinese Regulators Resort to Suspension of IPOs. FinanceAsia, July 6.

http://www.financeasia.com/News/399518,chinese-regulators-resort-to-suspension-of-ipos.aspx

Recent issues of FRBSF Economic Letter are available at

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/

2016-17

Household Formation among Young Adults

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economicletter/2016/may/household-formation-among-young-adults/

Furlong

2016-16

Economic Outlook: Springtime Is on My Mind

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economicletter/2016/may/economic-outlook-springtime-is-on-my-mind-sacramentospeech/

Williams

2016-15

Medicare Payment Cuts Continue to Restrain Inflation

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economicletter/2016/may/medicare-payment-cuts-affect-core-inflation/

Clemens / Gottlieb /

Shapiro

2016-14

Aggregation in Bank Stress Tests

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economicletter/2016/may/aggregating-data-in-bank-stress-test-models/

Hale / Krainer

2016-13

The Elusive Boost from Cheap Oil

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economicletter/2016/april/elusive-boost-from-cheap-oil-consumer-spending/

Leduc / Moran /

Vigfusson

2016-12

Data Dependence Awakens

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economicletter/2016/april/data-dependence-awakens-monetary-policy/

Pyle / Williams

Pacific Basin Notes are published occasionally by the Center for Pacific Basin Studies.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of

the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the Board of

Governors of the Federal Reserve System, or the Bank for International Settlements.

This publication is edited by Anita Todd. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole

articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint

permission to Research.Library.sf@sf.frb.org.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Alti, A. (2006) PDFDocument30 paginiAlti, A. (2006) PDFtiti fitri syahidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weekly Market Commentary 04132015Document4 paginiWeekly Market Commentary 04132015dpbasicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance of Private Equity-Backed IPOs. Evidence from the UK after the financial crisisDe la EverandPerformance of Private Equity-Backed IPOs. Evidence from the UK after the financial crisisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aydogan Alti 2006Document30 paginiAydogan Alti 2006i_jibran2834Încă nu există evaluări

- A Top Down Look at The Chinese Equity MarketDocument8 paginiA Top Down Look at The Chinese Equity Marketgo joÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of IPO On The Secondary Stock Market-An Empirical ResearchDocument8 paginiThe Impact of IPO On The Secondary Stock Market-An Empirical ResearchArun MaxwellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accounting Disclosures, Accounting Quality and Conditional and Unconditional ConservatismDocument39 paginiAccounting Disclosures, Accounting Quality and Conditional and Unconditional ConservatismNaglikar NagarajÎncă nu există evaluări

- China Spotlight When The Music Stops PDFDocument4 paginiChina Spotlight When The Music Stops PDFfajarz8668Încă nu există evaluări

- Quantum Strategy II: Winning Strategies of Professional InvestmentDe la EverandQuantum Strategy II: Winning Strategies of Professional InvestmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trade Based ManipulationDocument16 paginiTrade Based Manipulationgogayin869Încă nu există evaluări

- Alti On Timing and Capital Structure 2006 JF PDFDocument30 paginiAlti On Timing and Capital Structure 2006 JF PDFRyal GiggsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aquilo Capital 1Q2011 Investor LetterDocument2 paginiAquilo Capital 1Q2011 Investor Letterblanche21Încă nu există evaluări

- Z-Ben Executive Briefing (March 2012)Document2 paginiZ-Ben Executive Briefing (March 2012)David QuahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research A Field Guide To Emerging Market DividendsDocument12 paginiResearch A Field Guide To Emerging Market DividendsAmineDoumniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Concentration FinalDocument28 paginiGlobal Concentration FinaljamilkhannÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Factors That Affect Shares' ReturnDocument13 paginiThe Factors That Affect Shares' ReturnCahMbelingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blum RachelDocument31 paginiBlum RachelSaravanan SugumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- TomT Stock Market Model October 30 2011Document20 paginiTomT Stock Market Model October 30 2011Tom TiedemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Video 15Document18 paginiVideo 15gogayin869Încă nu există evaluări

- The Alchemy of Investment: Winning Strategies of Professional InvestmentDe la EverandThe Alchemy of Investment: Winning Strategies of Professional InvestmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- China S Stock Market VolatilityDocument8 paginiChina S Stock Market Volatilitygabriel chinechenduÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dao of Corporate Finance, Q Ratios, and Stock Market Crashes, by Mark SpitznagelDocument11 paginiThe Dao of Corporate Finance, Q Ratios, and Stock Market Crashes, by Mark Spitznagelxyz321321321100% (2)

- A PROJECT REPORT On Construction of Balanced Portfolio Comprising of Equity and Debt at SCMDocument115 paginiA PROJECT REPORT On Construction of Balanced Portfolio Comprising of Equity and Debt at SCMEr Tanmay MohantaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lectura Unidad 2 - Equity Artículos 3 y 4Document44 paginiLectura Unidad 2 - Equity Artículos 3 y 4Maria Del Mar LenisÎncă nu există evaluări

- TermProject SabitovaDocument22 paginiTermProject SabitovaSamar El-BannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Predictive Power of Weekly Fund Flows: Equity StrategyDocument32 paginiPredictive Power of Weekly Fund Flows: Equity StrategyCoolidgeLowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artikel 8B - Bova (2018) Discussion of Avoiding Chinas Capital MarketDocument4 paginiArtikel 8B - Bova (2018) Discussion of Avoiding Chinas Capital MarketZheJk 26Încă nu există evaluări

- Capital Markets in 2025Document15 paginiCapital Markets in 2025vatarplÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic Analysis of Ipo Underpricing in Stock MarDocument8 paginiEconomic Analysis of Ipo Underpricing in Stock MarRishita RajÎncă nu există evaluări

- CLSA and Olam ResearchDocument3 paginiCLSA and Olam ResearchCharles TayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capital for Champions: SPACs as a Driver of Innovation and GrowthDe la EverandCapital for Champions: SPACs as a Driver of Innovation and GrowthÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Drives Differences in UnderpricingDocument23 paginiWhat Drives Differences in Underpricinggogayin869Încă nu există evaluări

- IPOsDocument186 paginiIPOsBhaskkar SinhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Empirical Study On IPO Underpricing of The Shanghai A Share MarketDocument5 paginiAn Empirical Study On IPO Underpricing of The Shanghai A Share MarketKurapati VenkatkrishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 1007@BF02885725Document9 pagini10 1007@BF02885725gogayin869Încă nu există evaluări

- Summers BPEA 1981Document74 paginiSummers BPEA 1981Un OwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macroeconomics Cia-3: Nikitha M 1837044 I MaecoDocument5 paginiMacroeconomics Cia-3: Nikitha M 1837044 I MaecoNikitha MÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Ijafmrdec20181Document10 pagini1 Ijafmrdec20181TJPRC PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- IPO Chinese StyleDocument72 paginiIPO Chinese StyleAriSBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factor Investing SSRN-id2846982Document31 paginiFactor Investing SSRN-id2846982Vandemonia HWÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Cross-Asset Investment Research: A Review of ETF Alternatives Investors Should ConsiderDocument7 paginiInternational Cross-Asset Investment Research: A Review of ETF Alternatives Investors Should ConsiderWilson Pepe GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- SSRN Id2891434Document81 paginiSSRN Id2891434Loulou DePanamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weekly Xxvix - July 18 To 22, 2011Document2 paginiWeekly Xxvix - July 18 To 22, 2011JC CalaycayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Leverage As A Predictor of Financial Stability During Economic DistressDocument4 paginiFinancial Leverage As A Predictor of Financial Stability During Economic DistressDmytro Matthew KulakovskyiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wrigley AnalysisDocument140 paginiWrigley AnalysisBoonggy Boong25% (4)

- PWC Pharma Deals Insight q2 2015Document16 paginiPWC Pharma Deals Insight q2 2015seemaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Fund Management China 11Document89 paginiForeign Fund Management China 11Ning JiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Working Capital Management - PharmaDocument26 paginiWorking Capital Management - PharmaKshitij MittalÎncă nu există evaluări

- CampelloSaffi15 PDFDocument39 paginiCampelloSaffi15 PDFdreamjongenÎncă nu există evaluări

- EJMCM Volume 7 Issue 10 Pages 3860-3866Document7 paginiEJMCM Volume 7 Issue 10 Pages 3860-3866Evamary DanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Short-And Long-Run Effects of Going Public: Evidence From IPO FirmsDocument18 paginiThe Short-And Long-Run Effects of Going Public: Evidence From IPO FirmsMohit SonyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Primer On The Financial Policies of Chinese Firms: Takeaways From A Multi-Country ComparisonDocument20 paginiA Primer On The Financial Policies of Chinese Firms: Takeaways From A Multi-Country ComparisonYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Private Equity in China, 2012 - 2013Document16 paginiPrivate Equity in China, 2012 - 2013pfuhrmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Example Paper 4Document6 paginiExample Paper 4Rajendra Gibran Alvaro RamadhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asset Growth Cross Section of Stock ReturnsDocument54 paginiAsset Growth Cross Section of Stock ReturnsRaúl MorenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Luigi Zingales - Informe Mercado Financiero - 2022Document92 paginiLuigi Zingales - Informe Mercado Financiero - 2022Contacto Ex-AnteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capital Flows To Emerging MarketsDocument36 paginiCapital Flows To Emerging MarketsaflagsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Low Price-To-Book-Value Stocks: Finding The Winners AmongDocument4 paginiLow Price-To-Book-Value Stocks: Finding The Winners AmongNikunj PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q 12011 QuarterlyDocument4 paginiQ 12011 QuarterlyedoneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Private Equity Performance: What Do We Know?: Robert S. Harris, Tim Jenkinson and Steven N. KaplanDocument50 paginiPrivate Equity Performance: What Do We Know?: Robert S. Harris, Tim Jenkinson and Steven N. KaplanMonPolCenÎncă nu există evaluări

- ES Jatin2016 PDFDocument41 paginiES Jatin2016 PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- SSC CGL Economics Capsule 2015Document14 paginiSSC CGL Economics Capsule 2015swapnil_6788Încă nu există evaluări

- Phase2 Management EBook1Document20 paginiPhase2 Management EBook1tanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Highlights 14thfinance Commission Report PDFDocument2 paginiHighlights 14thfinance Commission Report PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- BFS Roundup FLIP 210 PDFDocument4 paginiBFS Roundup FLIP 210 PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Economics - IAS Mains Paper PDFDocument62 paginiEconomics - IAS Mains Paper PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Concept of Economic Development and Its MeasurementDocument27 paginiConcept of Economic Development and Its Measurementsuparswa88% (8)

- FM Ebook4Document69 paginiFM Ebook4tanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- 1469769616CareerAnna Ebook1 IntroductionToBankingDocument10 pagini1469769616CareerAnna Ebook1 IntroductionToBankingtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- June Facts PDFDocument16 paginiJune Facts PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Career Anna Rbiesiebook2Document54 paginiCareer Anna Rbiesiebook2tanyaa90100% (1)

- Financial Study Notes RBI Grade B Phase IIDocument35 paginiFinancial Study Notes RBI Grade B Phase IIKapil MittalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phase2 Management EBook2Document22 paginiPhase2 Management EBook2tanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Basic Calculation For IBPS Clerk - BSC4SUCCESSDocument3 paginiBasic Calculation For IBPS Clerk - BSC4SUCCESStanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- History of BankingDocument54 paginiHistory of BankingmansamratÎncă nu există evaluări

- Org Heads PDFDocument4 paginiOrg Heads PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Bankers Adda - Mission IBPS Exam - Rules of Paragraph Jumbles (Sentence Re-Arrangement)Document8 paginiBankers Adda - Mission IBPS Exam - Rules of Paragraph Jumbles (Sentence Re-Arrangement)tanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Bankers Adda - Mission IBPS Exam - English (Mix Quiz)Document3 paginiBankers Adda - Mission IBPS Exam - English (Mix Quiz)tanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Fiduciary Note Note Note Note Note Fiduciary Note FiduciaryDocument1 paginăFiduciary Note Note Note Note Note Fiduciary Note Fiduciarytanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Bankers Adda - Mission IBPS Exam - English Mix Quiz (For IBPS PO and RRB PO) PDFDocument3 paginiBankers Adda - Mission IBPS Exam - English Mix Quiz (For IBPS PO and RRB PO) PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Banking AwarenessDocument73 paginiBanking Awarenesstanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Banking and Finanac PDFDocument28 paginiBanking and Finanac PDFVijendra ThakreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Economy Quiz PDFDocument22 paginiIndian Economy Quiz PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- White and Brown Level AtmsDocument2 paginiWhite and Brown Level AtmsMahesh ChavanÎncă nu există evaluări

- L-7 Statistical Methods PDFDocument27 paginiL-7 Statistical Methods PDFkhanzuberÎncă nu există evaluări

- L-10 Income FlowsDocument11 paginiL-10 Income FlowsNitin PathakÎncă nu există evaluări

- L-8 Index Numbers (Meanings and Its Construction) PDFDocument15 paginiL-8 Index Numbers (Meanings and Its Construction) PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- Rbi Liquidity ManagementDocument3 paginiRbi Liquidity ManagementMahesh ChavanÎncă nu există evaluări

- L-9 Index Numbers (Problems and Uses) PDFDocument9 paginiL-9 Index Numbers (Problems and Uses) PDFtanyaa90Încă nu există evaluări

- AOM 2023-004 Understated Due To NGADocument4 paginiAOM 2023-004 Understated Due To NGAKean Fernand BocaboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re231123123nur Rdssfsfan Final Assignment - ECO101Document4 paginiRe231123123nur Rdssfsfan Final Assignment - ECO101Turhan PathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exam 8 June 2017, Questions - Asistensi AMB - Pertemuan 5 - Naura Rista Haniffah 1 Problem 1 Harley - StuDocuDocument1 paginăExam 8 June 2017, Questions - Asistensi AMB - Pertemuan 5 - Naura Rista Haniffah 1 Problem 1 Harley - StuDocuTadesse MolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 Wegagen Bank Ar 2009-10Document52 pagini01 Wegagen Bank Ar 2009-10Ajmel Azad Elias100% (8)

- Econ11 - Course Outline 2nd Sem 2011-12Document3 paginiEcon11 - Course Outline 2nd Sem 2011-12Quinnee VallejosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 - Discussion - Process Cost System - StudentsDocument2 pagini7 - Discussion - Process Cost System - StudentsCharles TuazonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greg Morris - 2017 Economic & Investment Summit Presentation - Questionable PracticesDocument53 paginiGreg Morris - 2017 Economic & Investment Summit Presentation - Questionable Practicesstreettalk700Încă nu există evaluări

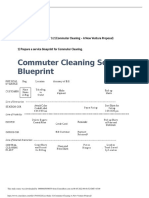

- Commuter Cleaning Service Blueprint: Racheal Atherton MGT 560 Operations ManagementDocument2 paginiCommuter Cleaning Service Blueprint: Racheal Atherton MGT 560 Operations Managementalan learnsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals of Cost Accounting 4th Edition Lanen Solutions Manual DownloadDocument51 paginiFundamentals of Cost Accounting 4th Edition Lanen Solutions Manual DownloadVerna English100% (23)

- Solved Problems Cost of CapitalDocument16 paginiSolved Problems Cost of CapitalPrramakrishnanRamaKrishnan0% (1)

- Corporate FinanceDocument24 paginiCorporate Financehello_world_111100% (3)

- Financial and Managerial Accounting The Basis For Business Decisions 18th Edition Williams Solutions ManualDocument87 paginiFinancial and Managerial Accounting The Basis For Business Decisions 18th Edition Williams Solutions ManualEmilyJonesizjgp100% (17)

- Case Study - Verloop - Edited - 1 - Compressed-1648107071325Document33 paginiCase Study - Verloop - Edited - 1 - Compressed-1648107071325Mark Henry Monasterial100% (2)

- ABB's Ratio Analysis 2011Document64 paginiABB's Ratio Analysis 2011PrakashGgiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hbs Case - Ust Inc.Document4 paginiHbs Case - Ust Inc.Lau See YangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Management (Problems)Document12 paginiFinancial Management (Problems)Prasad GowdÎncă nu există evaluări

- DellDocument7 paginiDellJune SueÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12 Business PlanningDocument24 pagini12 Business PlanningKhian PinedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise Chapter 4Document7 paginiExercise Chapter 4truongvutramyÎncă nu există evaluări

- SummaryDocument1 paginăSummaryherrajohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- B2B-All ModulesDocument483 paginiB2B-All ModulesakbarÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Perspective For The Luxury Goods Industry During and After CoronavirusDocument6 paginiA Perspective For The Luxury Goods Industry During and After CoronavirusFranck MauryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Management - Mildred G. AvilesDocument63 paginiFinancial Management - Mildred G. AvilesCoy ApuyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA Finance & Accounts With 14 Years of Experiance - Chandra Sekhar DoraDocument4 paginiMBA Finance & Accounts With 14 Years of Experiance - Chandra Sekhar DoraYamini SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Need of The Study: Ratio Analysis and Comparative Study of Ratios of HPCL With Its CompetitorsDocument76 paginiNeed of The Study: Ratio Analysis and Comparative Study of Ratios of HPCL With Its Competitorssavita acharekarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Horizontal Analysis: Lesson 2.7Document19 paginiHorizontal Analysis: Lesson 2.7JOSHUA GABATEROÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cfas Inventories QuizletDocument2 paginiCfas Inventories Quizletagm25Încă nu există evaluări

- AI-X-S7-G5-Arief Budi NugrohoDocument9 paginiAI-X-S7-G5-Arief Budi Nugrohoariefmatani73Încă nu există evaluări

- Travel Agency Marketing PlanDocument15 paginiTravel Agency Marketing PlanReshma Walse50% (2)

- Chopra3 PPT ch01Document39 paginiChopra3 PPT ch01Rachel HasibuanÎncă nu există evaluări