Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Rehabilitation European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention

Încărcat de

PitoAdhiTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Rehabilitation European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention

Încărcat de

PitoAdhiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention

& Rehabilitation

http://cpr.sagepub.com/

Six-minute walking test after cardiac surgery: instructions for an appropriate use

Stefania De Feo, Roberto Tramarin, Roberto Lorusso and Pompilio Faggiano

European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation 2009 16: 144

DOI: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328321312e

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://cpr.sagepub.com/content/16/2/144

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

European Society of Cardiology

European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation

Additional services and information for European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://cpr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://cpr.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Apr 1, 2009

What is This?

Downloaded from cpr.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on June 16, 2014

Review Paper

Six-minute walking test after cardiac surgery: instructions

for an appropriate use

Stefania De Feoa, Roberto Tramarinb, Roberto Lorussoc

and Pompilio Faggianod

a

Cardiology Department, Casa di Cura Polispecialistica Dr Pederzoli, Peschiera del Garda, Verona,

Cardiac Rehabilitation Unit, Fondazione Europea Ricerca Biomedica Onlus, Cernusco S/N, Milano,

c

Cardiac Surgery Division and dCardiology Division, Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy

b

Received 7 August 2008 Accepted 5 November 2008

The 6-min walking test is a practical, simple, inexpensive test, which does not require any exercise equipment or advanced

training. The test has been proposed both as a functional status indicator and as an outcome measure in various

categories of patients (postmyocardial infarction, heart failure, postcardiac surgery) admitted to rehabilitation programs.

The purpose of this study is to review the literature regarding the usefulness of 6-min walking test for the evaluation of

patients entering a cardiac rehabilitation program early after cardiac/thoracic surgery. The test is feasible and safe, even in

elderly and frail patients, shortly after admission to an in-hospital rehabilitation program. The results of the test is

influenced by many demographic and psychological variables, such as age, sex (with women showing lower functional

capacity), comorbidity (particularly diabetes mellitus, arthritis, and other musculoskeletal diseases), disability, self-reported

physical functioning, and general health perceptions; contrasting data correlate walked distance with left ventricular

ejection fraction. Practical suggestions for test execution and results interpretation in this specific clinical setting are given

c 2009 The European Society of Cardiology

according to current evidence. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 16:144149

European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation 2009, 16:144149

Keywords: cardiac rehabilitation, cardiac and thoracic surgery, functional capacity, 6-min walking test

Introduction

The 6-min walking test (6MWT) is used to measure the

maximum distance that a person can walk in 6 min. The

test is a modification of the 12-Minute Walk-Run Test

originally developed by Cooper [1] as a field test to

predict maximal oxygen uptake.

The 6MWT was first used by pneumologists to evaluate

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases

(COPD) and respiratory failure and then by cardiologists

to assess the functional status of patients with severe

cardiovascular diseases [2], the effects of therapy and to

predict morbidity and mortality in patients with left

ventricular dysfunction [3] and advanced heart failure

[47]. The widespread acceptance of walk tests relates to

their convenience, low cost, and presumed ease of

completion. The traditional functional test in cardiac

Correspondence to Dr Pompilio Faggiano, Via Trainini 14, Brescia 25133, Italy

Tel: + 39 030 3995573; fax: + 39 030 2007785; e-mail: faggiano@numerica.it

rehabilitation has been the symptom-limited exercise

test with bicycle or treadmill. This test, however, might

not be suitable for older adults as they tend to have poor

balance, poor neuromuscular coordination, impaired

vision, abnormal gait patterns, and might experience fear

of exercising. In contrast, the 6MWT test has close

similarities to daily living activities and can be carried out

even by many elderly and severely limited patients who

are not able to perform symptom-limited exercise tests,

as are cardiac patients after recent major surgery.

The test has been also proposed in various categories of

patients (postmyocardial infarction, chronic heart failure,

postcardiac surgery) admitted to cardiac rehabilitation

programs both as a functional status indicator and as an

outcome measure.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the utility of the

6MWT for the evaluation of patients entering a cardiac

c 2009 The European Society of Cardiology

1741-8267

DOI: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328321312e

Downloaded from cpr.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on June 16, 2014

Copyright Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

6-min walk test after cardiac surgery Feo et al. 145

rehabilitation program early after a cardiac/thoracic

surgery procedure.

Reliability and validity of the test

Several studies have shown that the test is feasible and

safe, even in elderly and frail patients, shortly after

admission to an in-hospital rehabilitation program. In

patients entering a cardiac rehabilitation program early

after cardiac surgery, the 6MWT is well tolerated and no

cardiopulmonary complications are reported [811].

Several factors are known to potentially influence the

results of walk tests. A training effect is well documented

in the performance of walk tests [12]. According to the

American Thoracic Society (ATS) review of previously

published 6MWT studies and guidelines, the increase in

walking distance because of the learning effect ranges

from a mean of 0 to 17% [7]. Performance usually reaches

a plateau after two walk tests done within a week. Larson

and colleagues [13] had 48 participants with COPD

performing four 12-min walks at 1-week intervals.

Average walk distances improved significantly through

the third test. Differences of 46 m (151 ft) occurred

between the first and second walks, and 78 m (256 ft)

between the first and third walks. Similar results have been

reported by other investigators [14,15]. The reproducibility

results from one study of 112 patients with stable severe

COPD suggest that an increase of at least 70 m in the

distance walked during the 6MWT after an intervention is

necessary to be 95% confident that the improvement in

functional capacity is a true consequence of the therapeutic

measure and not intertest variability [16].

Most programs surveyed using 6MWT usually provide

verbal encouragement to patients while walking, although

Table 1

not always consistently. The effect of encouragement on

test outcomes was studied by Guyatt and colleagues [17].

Inclusion of standardized encouraging phrases to patients

every 30 s was associated with an average increase of

30.5 m (100 ft) in distance walked, compared with

distances achieved when the supervisor remained silent.

Moreover, other factors such as instructions given prior

walking, monitoring during walks, awareness of distances

accomplished while walking, directions given to patients

while walking, and positioning of the tester (walking with

the patient vs. technician stationary in one area of the

track) can significantly influence walking performance.

The American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary

Rehabilitation stated the value of timed distance walk tests

as outcome measures for pulmonary rehabilitation, and

cautioned of the need to standardize test procedures

[18]. In 2002, an ATS statement was published on

6MWT, including the standard procedure for conducting

the walking test, to provide useful and comparable

information [7] (Table 1). According to this guideline,

the test should be supervised by cardiac rehabilitation

professionals (presence of a physician is not required)

although all testers are trained in advanced cardiac life

support, and resuscitation equipment is immediately

available. The test might be carried out, if indicated by

the physician, using telemetry monitoring. Participants

are asked to walk at their own maximal pace along a flat

and straight hospital corridor of at least 30 m in length.

The instructions are given to participants before the test

and during the walk encouragement is provided at

intervals, to comfort the patient who might find it

awkward to walk in silence for 6 min. Blood pressure and

heart rate are measured before and after testing.

Monitoring of oxygen saturation during testing is not

mandatory, but such monitoring might occasionally add

Six-minute walk test protocol [7]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications: unstable angina, recent history of myocardial infarction or cardiac dysrhythmia.

Relative contraindications: resting heart rate of more than 120, uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure of more than 180 mmHg, and diastolic blood

pressure of more than 100 mmHg). Stable exertional angina is not an absolute contraindication for a 6MWT, but patients with these symptoms should perform the test

after using their antiangina medication, and rescue nitrate medication should be readily available.

Procedure

Resting vital signs are recorded before walk: blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse oximetry (if indicated).

The 6MWT should be performed indoors, along a long, flat, straight, enclosed corridor with a hard surface that is seldom traveled. The walking course must be 30 m in

length.

Instruct the patient as follows: The object of this test is to walk as far as possible for 6 min. You will walk back and forth in this hallway. Six minutes is a long time to walk,

so you will be exerting yourself. You will probably get out of breath or become exhausted. You are permitted to slow down, to stop, and to rest as necessary. You may

lean against the wall while resting, but resume walking as soon as you are able.

You will be walking back and forth around the cones. You should pivot briskly around the cones and continue back the other way without hesitation. Now Im going to

show you. Please watch the way I turn without hesitation.

Demonstrate by walking one lap yourself. Walk and pivot around a cone briskly.

Are you ready to do that? I am going to use this counter to keep track of the number of laps you complete. I will click it each time you turn around at this starting line.

Remember that the object is to walk as far as possible for 6 min, but dont run or jog. Start now, or whenever you are ready.

Position the patient at the starting line. Stand near the starting line during the test. Do not walk with the patient.

During the walk, words of encouragement are provided at 1-min time interval, such as You are doing well, Keep up the good work. Do not use other words of

encouragement (or body language to speed up).

Posttest: record the postwalk Borg dyspnea and fatigue levels and ask this: What, if anything, kept you from walking farther?

Distance walked is measured and recorded to the nearest foot. If patient had to stop and rest, the duration of the rest time is recorded.

Record patients blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse oximetry (if indicated).

Staff member who administered the test will sign and date the form.

Downloaded from cpr.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on June 16, 2014

Copyright Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

146

European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation 2009, Vol 16 No 2

clinical data in selected patients with concomitant heart

and lung diseases and elevated pulmonary arterial

pressures. Standardization of encouragement may be of

value. The test is symptom-limited, therefore patients are

allowed to stop if signs or symptoms of significant distress

occur (severe dyspnea, dizziness, angina, skeletal muscle

pain), though they are instructed to resume walking as soon

as possible. The distance covered during the test is

recorded in meters. Secondary measures can include

fatigue and dyspnea, measured with a modified Borg or

visual analogue scale, and presence or severity of angina [7].

Determinants of walk performance

Several studies have reported that functional capacity is

affected by demographic variables, such as sex and age:

the distance walked is greater in men than women and

inversely related to age [1927], perhaps reflecting

problems with balance and joints and progressive

reduction of skeletal muscle mass and strength in older

participants. The dependence of distance walked from

sex and age underlines the need for expressing the results

of 6MWT both as an absolute value in meters and as

a percentage of the predicted value, according to the

reference equation published previously [11]. Expressing

the distance walked in these two different ways (absolute

value and percentage of predicted value) might have

clinical relevance. In fact, the same absolute distance

walked, 250 m for example, may be within the normal

range for an 80-year-old man and severely reduced for

a 45-year-old man. Instead, the percentage of predicted

value, taking into account demographic and anthropometric

variables such as sex, age, weight, and height, allows

physicians to express the functional capacity of an individual

participant compared with the healthy population with

similar demographic characteristics. In contrast, the

result expressed as an absolute value can be more

appropriate when evaluating the effects of therapeutic

interventions in the single patient.

In studies including patients enrolled in cardiac

rehabilitation program early after cardiac surgery, the

presence of one or more comorbid conditions (particularly

diabetes mellitus, arthritis, and other musculoskeletal

diseases) and inactive physical state negatively affected

the walking performance, independently of sex and age

[9,28]. Fiorina et al. [9] found that distance walked was

significantly shorter at 6MWT carried out in patients early

after cardiac surgery compared with patients early after

acute myocardial infarction. Several factors, including

postoperative prolonged bed rest, chest pain and

respiratory limitation following sternotomy may be

responsible for this difference.

Contrasting data have been reported on the influence of

postoperative left ventricular function on distance walked

before the rehabilitation program. In one large study, no

relation was found between left ventricular ejection

fraction and the results of 6MWT [9]. In contrast, in

other studies a poor left ventricular systolic function

negatively influenced the distance walked in all patients

[2931] or only in men, but not in women [28], possibly

as a consequence of physical deconditioning in patients

with cardiac dysfunction and higher left ventricular

ejection fraction usually observed in women. Of interest,

an improvement in distance walked at 6MWT carried out

at the end of the cardiac rehabilitation program, compared

with early postoperative test, was observed in most

patients, independently from presence or absence of left

ventricular systolic dysfunction [9,30,32]; moreover, in the

study of Polcaro et al. [30] the relative increase in distance

walked from baseline was significantly larger in patients

with left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%,

compared with those with left ventricular ejection fraction

greater than 40% (36 vs. 23%). Accordingly, these data

confirm that a left ventricular dysfunction does not

represent a contraindication to a physical program, even

in cardiac surgery patients.

Clinical conditions, such as anemia or atrial fibrillation,

frequently observed early after cardiac surgery, are known

to negatively affect the walking performance [33,34].

The 6MWT, however, can be performed safely, although

relative contraindications to the test include a resting

heart rate of more than 120 bpm [7].

Walk performance also correlates with history of

sedentary lifestyle, patient self-reported physical activity

levels, and physical function as determined by the Short

Form-36 questionnaire [35] and disability [36]. In a study

on old people in community centres and retirement homes

in the Los Angeles area, the 6-min walk distance was

significantly greater for active than for inactive older adults,

moderately correlated with chair stands, standing balance,

and gait speed. It had a low correlation with body mass

index. The study showed a moderate correlation of the

6MWT with self-reported physical functioning and general

health perceptions. Self-report and performance measures

explained 69% of the variance in 6-min walk scores.

In a cardiac rehabilitation population with milder disease

setting (mean age of patients 63 10 years), the 6-min walk

was moderately correlated with scores of quality of life

questionnaires, such as the Activity Status Index (r = 0.502,

P < 0.001) and the Physical Function subscale of the Short

Form 36 Health Survey (r = 0.624, P < 0.001) [37].

In a previous study carried out with elderly patients

admitted to cardiac rehabilitation unit early after cardiac

surgery, the 6MWT performed within the first week of

hospital admission was feasible and safe [38]. The timing

of the test and the walking performance were strongly

influenced by the patients disability and dependence

Downloaded from cpr.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on June 16, 2014

Copyright Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

6-min walk test after cardiac surgery Feo et al. 147

level, as assessed by nursing needs. Moreover, the walking

capacity affected the patients self-perceived health

status and identified more severely compromised patients

with lower susceptibility to recovery; interestingly, even

in the elderly, functional capacity is still affected by age

and sex, with a decreasing performance in older patients

and in females [8,38].

The correlation between the walk performance and

standard assessment of exercise capacity, such as the

symptom-limited exercise test, has not been widely

investigated in cardiac rehabilitation setting. One study

conducted on a small group of patients admitted to a

cardiac rehabilitation program has compared the results of

the 6MWT and those of a symptom-limited graded

exercise test. The 6MWT was linearly related to peak

oxygen uptake, as expressed by exercise metabolic

equivalents (r = 0.687, P < 0.001), with maximum metabolic equivalents accounting for 47% of the variance in

distance walked, hence supporting the validity of the test

[39]. In a study that enrolled only 10 elderly patients who

underwent cardiac surgery 3 months before, distance

walked at 6MWT was highly and significantly correlated

(r = 0.93) with functional capacity assessed at symptomlimited graded exercise testing [40]. Accordingly, it is

possible to argue that factors associated with a shorter

distance walked at 6MWT are similar to those associated

with a reduced peak oxygen uptake at maximal exercise,

as reported by previous investigators. In this perspective,

the value of the 6MWT as alternative to symptom-limited

exercise test, with or without oxygen uptake, should be

confirmed.

Interpreting the results

Exercise testing is a key component of the initial

assessment performed when a patient is enrolled in

a cardiac rehabilitation program, and the evaluation of

change in functional capacity has become a common

clinical outcome in cardiac rehabilitation programs [18].

Assessment of functional capacity at program entry can be

an effective tool for appropriate exercise prescription in

any single patient. Several studies have shown that the

6MWT is safe and reliable within the first few days of

admission in a rehabilitation program after cardiac surgery.

This finding is relevant as the evaluation of individual

patient functional capacity may provide important

information to guide exercise training prescription. In

fact, for cardiac patients to achieve favorable physical

training responses, and enable the appropriate prescription of physical activities, it is important that functional

physical capacity be established and it is recommended to

provide flexible programs and that exercise intensity be

prescribed relative to fitness level [41].

Distance walked also provides prognostic information

beyond the clinical assessment. Poor performance on

6MWT at the entry can be useful in the identification of

those patients who are more deconditioned and might

gain more at the end of their rehabilitation program [9].

A poor 6MWT performance on admission identifies

patients with a longer rehabilitation stay; these patients

also have significant persistent functional impairment at

discharge [9,28].

The distance that the patient can walk may be used

either as a generic one-time measure of functional status

or as an outcome measure for the rehabilitation program.

In fact, the 6MWT is also a valuable instrument to assess

progression of functional capacity in different clinical

intervention studies [4245]. The definition of clinical

outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation programs plays

a pivotal role. Outcome indicators have been included

in the Best Practice Guidelines because it is difficult

to monitor a number of outcomes usually requiring

long-term follow-up. Further testing of the recommended

process and outcome indicators is required to identify

suitable benchmarks.

The average age of individuals undergoing coronary artery

bypass grafting or valve procedure has progressively

increased and nearly 30% of surgical patients are now

above 70 years of age. In this context, the 6MWT might

play a role as a submaximal measure of the functional

impairment that is more accessible and user friendly. The

6MWTusually improves at the end of cardiac rehabilitation

program: the increase in distance walked does not seem to

be affected by age, sex, diabetes, type of surgery (valve or

coronary), and left ventricular function, and is 30% on

average [9]. Of interest, those patients walking longer at

baseline have less room for improvement, with a sort of

ceiling effect, whereas a greater impairment of functional

capacity at the beginning of the cardiac rehabilitation

program is the main determinant of the magnitude of the

walk test performance improvement [9]. It is, however,

important to realize that the relationship between walking

distance and long-term mortality or hospitalization has not

been validated in a cardiac rehabilitation population.

As emphasized before, the results of the 6MWT can be

given as an absolute value (meters or feet) or as a

percentage of the predicted distance using equations

from published studies of healthy people of the same age

group [11,20,25]. Furthermore, for a correct interpretation of the distance walked, Opasich et al. [28] proposed

to compare this value with a specific reference value

derived from a population with the highest affinity to the

patient. The authors tried to develop an easy algorithm

from a large sample of patients performing a 6MWT

at admission to an intensive in-hospital rehabilitation

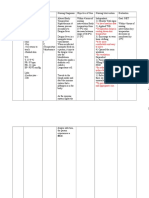

unit early after cardiac surgery (Fig. 1). Reference tables

were built up taking into account the variables,

which independently affected the distance walked:

demographic variables (sex and age), left ventricular

ejection fraction (only in men), and presence of any

Downloaded from cpr.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on June 16, 2014

Copyright Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

148

European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation 2009, Vol 16 No 2

comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus, renal failure,

chronic cerebrovascular diseases, and COPD). Once the

patient has been categorized according to these variables,

the distance walked can be compared with his or her

matched reference value, and the interpretation of the

result becomes more efficient (Tables 2 and 3).

Conclusion

The 6MWT is widely used for measuring the functional

status, targeted at people with at least moderate

functional impairment. The evaluation of the functional

physical capacity by means of 6MWT at entry of a cardiac

rehabilitation program early after cardiac surgery is

helpful to adapt the modalities of the training program

to obtain the best results at the most appropriate training

intensity. Specially in elderly patients, showing increased

prevalence of comorbidities, physical exercise programs

should be established according to the individual exercise

capacity. The 6MWT has been shown to be safe and well

accepted, even early after the intervention.

In recent years, the distance walked at the 6MWT has also

gained prominence for use in clinical practice and in a

research setting to assess changes in functional capacity

after cardiac rehabilitation programs, not only in heart

failure and postmyocardial infarction, but even in surgical

patients.

Some features must be taken into account in the

interpretation of the tests results. For example, participants

who are less motivated usually have shorter 6MWT

performance. The learning effect has been often described,

with better values obtained at a second testing, and the

need for multiple walk tests remains controversial. Nevertheless, repeated testing might be less applicable in

clinical settings and in more compromised patients, and

the majority of studies chose to use the results from a

single test administration.

Fig. 1

Male patient

Age?

Female patient

< 61/6170/>71 (years)

Age?

< 61/6170/ >71 (years)

50% /< 50%

LVEF?

Comorbidity?

Yes No

Diabetes

Creatinine >1.5 mg/dl

Cerebrovascular diseases

COPD

Comorbidity?

Yes No

However, use of walk tests to measure changes in

performance necessitates careful standardization of testing

procedures; in this perspective, the new ATS guidelines

provide a standardized approach for performing the 6MWT

to improve its clinical value.

Table 3 Reference values for the distance walked stratified by age

and comorbidity in women

Diabetes

Creatinine > 1.5 mg/dl

Cerebrovascular diseases

COPD

See Table 2

See Table 3

Algorithm suggested by Opasich et al. [28] for a correct interpretation

of the walking test in the individual patient early after cardiac surgery.

See the text for details. Source: modified from Opasich et al. [28].

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; LVEF, left ventricular

ejection fraction.

Absence of comorbidities

Mean SD

Median

Lower quartile

Upper quartile

Presence of comorbidities

Mean SD

Median

Lower quartile

Upper quartile

Age r 60

years

Age 6170

years

Age Z 71

years

n = 75

283 96

295

210

350

n = 83

267 100

275

200

340

n = 101

255 93

249

200

318

n = 151

220 86

220

160

280

n = 115

184 83

178

125

240

n = 149

207 105

200

132

280

Modified from Opasich et al. [28].

Table 2

Reference values for the distance walked stratified by age, LVEF, and comorbidity in men

Age r 60 years

Absence of

comorbidities

Mean SD

Median

Lower quartile

Upper quartile

Presence of

comorbidities

Mean SD

Median

Lower quartile

Upper quartile

Age 6170 years

Age Z 71 years

LVEF Z 50%

LVEF < 50%

LVEF Z 50%

LVEF < 50%

LVEF Z 50%

LVEF < 50%

n = 205

n = 119

n = 191

n = 108

n = 113

n = 79

369 92

370

310

427

n = 109

360 90

360

310

420

n = 63

330 98

340

260

400

n = 156

302 101

309

241

377

n = 105

310 113

300

220

390

n = 124

369 102

270

180

340

n = 85

346 102

350

292

416

341 89

344

282

400

326 109

334

250

400

282 100

286

220

360

287 122

284

200

371

254 119

2480

175

325

Modified from Opasich et al. [28]. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Downloaded from cpr.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on June 16, 2014

Copyright Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

6-min walk test after cardiac surgery Feo et al. 149

Acknowledgements

24

The authors state that (i) the paper is not under

consideration elsewhere, (ii) none of the papers contents

have been previously published, (iii) there was no support for

the work, (iv) they have read and approved the manuscript,

and (v) there is no potential conflict of interest.

7

8

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

26

27

References

1

25

Cooper KH. A means of assessing maximal oxygen uptake: correlation

between field and treadmill testing. JAMA 1968; 203:201204.

Kadikar A, Maurer J, Kesten S. The six-minute walk test: a guide to

assessment for lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1997;

16:313319.

Bittner V, Weiner DH, Yusuf S, Rogers W, McIntyre K, Bangdiwala SI, et al.

Prediction of mortality and morbidity with a 6-minute walk test in patients

with left ventricular dysfunction. JAMA 1993; 270:17021707.

Cahalin LP, Mathier MA, Semigran MJ, Dec GW, DiSalvo TG. The six-minute

walk test predicts peak oxygen uptake and survival in patients with advanced

heart failure. Chest 1996; 110:325332.

Opasich C, Pinna GD, Mazza A, Febo O, Riccardi R, Riccardi PG, et al.

Six-minute walking performance in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure;

is it a useful indicator in clinical practice? Eur Heart J 2001; 22:488496.

Faggiano P, DAloia A, Gualeni A, Brentana L, Dei Cas L. The 6 minute

walking test in chronic heart failure: indications, interpretation and limitations

from a review of the literature. Eur J Heart Fail 2004; 6:687691.

The American Thoracic Society. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute

walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166:111117.

De Feo S, Mazza A, Camera F, Maestri A, Opasich C, Tramarin R. Distance

covered in walking test after cardiac surgery in patients over 70 years of age:

outcome indicator for the assessment of quality of care in intensive

rehabilitation. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2003; 60:111117.

Fiorina C, Vizzardi E, Lorusso R, Maggio M, De Cicco G, Nodari S, et al. The

6-min walking test early after cardiac surgery. Reference values and the effects

of rehabilitation programme. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007; 32:724729.

Roomi J, Johnson MM, Waters K, Yohannes A, Helm A, Connolly MJ.

Respiratory rehabilitation, exercise capacity and quality of life in chronic

airways disease in old age. Age Ageing 1996; 25:1216.

Enright PL, McBurnie MA, Bittner V, Tracy RP, McNamara R, Arnold A, et al.

The 6 minute walk test: a quick measure of functional status in elderly adults.

Chest 2003; 123:387398.

Stevens D, Elpern E, Sharma K, Szidon P, Ankin M, Kesten S. Comparison of

Hall and Treadmill six-minute walk tests. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;

160:15401543.

Larson JL, Covey MK, Vitalo CA, Alex CG, Patel M, Kim MJ. Reliability and

validity of the 12-min distance walk in patients with chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. Nurs Res 1996; 45:203210.

Mungall IPF, Hainsworth R. Assessment of respiratory function in patients

with chronic obstructive airways disease. Thorax 1979; 34:254258.

McGavin CR, Gupta SP, McHardy GJR. Twelve-minute walking test for

assessing disability in chronic bronchitis. BMJ 1976; 1:822823.

Redelmeier DA, Bayoumi AM, Goldstein RS, Guyatt GH. Interpreting small

differences in functional status: the six minute walk test in chronic lung

disease patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155:12781282.

Guyatt GH, Pugsley SO, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, Berman L, Jones NL,

et al. Effect of encouragement on walking test performance. Thorax 1984;

39:818822.

American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation.

Guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs.

4th editon, Williams MA. editor. Champagne, IL: Human Kinetics; 2004.

Enright PL, Sherrill DL. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in

healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 158:13841387.

Trooster T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Six minute walking distance in healthy

elderly subjects. Eur Respir 1999; 14:270274.

Bendall MJ, Bassey EJ, Pearson MB. Factors affecting walking speed of

elderly people. Age Aging 1989; 18:327332.

Harada ND, Chiu V, Stewart AL. Mobility-related function in older adults:

assessment with a 6-minute walk test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;

80:837841.

Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test

performance in community-dwelling elderly people: six-minute walk test,

Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up & Go test and Gaited Speed. Phys Ther

2002; 82:128137.

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Gibbons WJ, Fruchter N, Sloan S, Levy RD. Reference values for a multiple

repetition 6-minute walk test in healthy adults older than 20 years.

J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2001; 21:8793.

Bohonnon RW. Comfortable and maximal walking speed of adults aged

2079 years: reference values and determinants. Age Ageing 1997; 26:

1519.

Lord SR, Menz HB. Physiologic, psychologic and health predictors of

6-minute walk performance in older people. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;

83:907911.

Duncan PW, Chandler J, Studenski S, Hughes M, Prescott B. How do

physiological components of balance affect mobility in elderly men? Arch

Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74:13431349.

Opasich C, De Feo S, Pinna GD, Furgi G, Pedretti R, Scrutinio D, Tramarin R.

Distance walked in the 6-minute test soon after cardiac surgery. Toward an

efficient use in the individual patient. Chest 2004; 126:17961801.

Tallaj JA, Sanderson B, Breland J, Adams C, Schumann C, Bittner V.

Assessment of functional outcomes using the 6-minute walk test in cardiac

rehabilitation: comparison of patients with and without left ventricular

dysfunction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2001; 21:221224.

Polcaro P, Molino Lova R, Guarducci L, Conti AA, Zipoli R, Papucci M, et al.

Left-ventricular function and physical performance on the 6-min walk test in

older patients after inpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil

2008; 87:4655.

Kervio G, Ville N, Leclercq C, Daubert JC, Carre F. Cardiorespiratory

adaptations during the six-minute walk test in chronic heart failure patients.

Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2004; 11:171177.

Hirschhorn AD, Richards D, Mungovan SF, Morris NR, Adams L. Supervised

moderate intensity exercise improves distance walked at hospital discharge

following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. A randomised controlled trial.

Heart Lung Circ 2008; 17:129138.

Chaves PHM, Ashar B, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Looking at the relationship

between hemoglobin concentration and prevalent mobility difficulty in older

women. Should the criteria currently used to define anemia in older people

be reevaluated? J Am Geriatr Soc 50:12571264.

Macchi C, Fattirolli F, Lova RM, Conti AA, Luisi ML, Intini R, et al. Early and

late rehabilitation and physical training in elderly patients after cardiac

surgery. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 86:826834.

Bittner V, Sanderson B, Breland J, Adams C, Schumann C. Assessing

functional capacity as an outcome in cardiac rehabilitation: role of the

6-minute walk test. Clin Exerc Physiol 2000; 21:1926.

Hamilton DM, Haennel RG. Validity and reliability of the 6-minute walk test

in a cardiac rehabilitation population. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2000; 20:

156164.

De Feo S, Opasich C, Capietti M, Cazzaniga E, Mazza A, Manera M, et al.

Functional and psychological recovery during intensive hospital

rehabilitation following cardiac surgery in the elderly. Monaldi Arch Chest

Dis 2002; 58:3540.

Kristjansdottir A, Ragnarsdottir M, Einarsson MB, Torfason B. A Comparison

of the 6-Minute Walk Test and Symptom Limited Graded Exercise Test for

Phase II Cardiac Rehabilitation of Older Adults. J Geriatric Physical Therapy

2004; 27:6568.

Bootsma-van der Wiel A, Gussekloo J, De Craen AJ, Van Exel E, Bloem BR,

Westendorp RG. Common chronic diseases and general impairments as

determinants of walking disability in the oldest-old population. J Am Geriatr

Soc 2002; 50:14051410.

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). Guidelines for exercise testing

and prescription. Baltimore, US: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Pu CT, Johnson MT, Forman DE, Hausdorff JM, Roubenoff R, Foldvari M,

et al. Randomized trial of progressive resistance training to counteract the

myopathy of chronic heart failure. J Appl Physiol 2001; 90:23412350.

Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Trueblood PR, Loy S, Harker JO,

Pietruszka FM, Robbins AS. Effects of a group exercise program on

strength, mobility, and falls among fall-prone elderly men. J Gerontol A Biol

Sci Med Sci 2000; 55:M317M321.

Berry MJ, Rejeski WJ, Adair NE, Zaccaro D. Exercise rehabilitation and

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1999; 160:12481253.

Criner GJ, Cordova FC, Furukawa S, Kuzma AM, Travaline JM, Leyenson V,

OBrien GM. Prospective randomized trial comparing bilateral lung volume

reduction surgery to pulmonary rehabilitation in severe chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:20182027.

Wright DJ, Khan KM, Gossage EM, Saltissi S. Assessment of a low intensity

cardiac rehabilitation programme using the six minute walk test. Clin Rehabil

2001; 15:119124.

Downloaded from cpr.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on June 16, 2014

Copyright Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- 6 Minute Walk Test Vs Shuttle Walk TestDocument3 pagini6 Minute Walk Test Vs Shuttle Walk TestcpradheepÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in The Evaluation of Unexplained Dyspnea - UpToDate PDFDocument37 paginiCardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in The Evaluation of Unexplained Dyspnea - UpToDate PDFGLORIA MARCELA ESTEVEZ RAMIREZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Six Minute Walk Test - : Nimisha B (MPT, Dyhe) Assisstant Professor Sacpms, MMC ModakkallurDocument16 paginiSix Minute Walk Test - : Nimisha B (MPT, Dyhe) Assisstant Professor Sacpms, MMC ModakkallurNimisha Balakrishnan100% (1)

- Gas Gangrene.Document24 paginiGas Gangrene.Jared GreenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preanesthesia IntroductionDocument38 paginiPreanesthesia IntroductionJovian LutfiÎncă nu există evaluări

- DENGUE CS NCP 1Document8 paginiDENGUE CS NCP 1Karyl SaavedraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tasc II 2015 Update On AliDocument15 paginiTasc II 2015 Update On AliPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Six Minute Walk TestDocument4 paginiThe Six Minute Walk Testhm3398Încă nu există evaluări

- Module1 HypnosisDocument95 paginiModule1 HypnosisImam Zakaria100% (1)

- Endoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment in Prostate Pathology: Handbook of EndourologyDe la EverandEndoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment in Prostate Pathology: Handbook of EndourologyPetrisor Aurelian GeavleteÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPG Management of Breast Cancer (2nd Edition) 2010 PDFDocument100 paginiCPG Management of Breast Cancer (2nd Edition) 2010 PDFNana Nurliana NoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physiotherapy Guideline: Queensland Cardiorespiratory Physiotherapy NetworkDocument20 paginiPhysiotherapy Guideline: Queensland Cardiorespiratory Physiotherapy NetworkBRDÎncă nu există evaluări

- E Cacy of Early Respiratory Physiotherapy and Mobilization After On-Pump Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Controlled TrialDocument15 paginiE Cacy of Early Respiratory Physiotherapy and Mobilization After On-Pump Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Controlled TrialAsmaa GamalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Six Minute Walk Test A Simple and Useful Test To Evaluate Functional Capacity in Patients With Heart Failure.Document8 paginiSix Minute Walk Test A Simple and Useful Test To Evaluate Functional Capacity in Patients With Heart Failure.Carolina Millan SalfateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstract BookDocument222 paginiAbstract BookArkesh PatnaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- The SF-36 and 6-Minute Walk Test Are Significant PredictorsDocument7 paginiThe SF-36 and 6-Minute Walk Test Are Significant PredictorsJimmy Sulca CorreaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tebbutt 2011Document6 paginiTebbutt 2011rimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Intradialytic Aerobic Exercise On Dialysis Efficacy in Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument5 paginiThe Effect of Intradialytic Aerobic Exercise On Dialysis Efficacy in Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Controlled TrialFitriatun NisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retired Firefighter of 40 Years Grateful For The Help of Doctors at HCA Florida MemorialDocument9 paginiRetired Firefighter of 40 Years Grateful For The Help of Doctors at HCA Florida MemorialSarah GlennÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Early Activity On Patients OutcomeDocument10 paginiThe Effect of Early Activity On Patients Outcomeanggaarfina051821Încă nu există evaluări

- Ergometer Cycling Improves The Ambulatory Function and Cardiovascular Fitness of Stroke Patients-A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument6 paginiErgometer Cycling Improves The Ambulatory Function and Cardiovascular Fitness of Stroke Patients-A Randomized Controlled Trialayu lestariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal 5Document6 paginiJournal 5Claudia JessicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use of The 6-Min Walk Test - A Pro and Con Review - The American College of Chest PhysiciansDocument5 paginiUse of The 6-Min Walk Test - A Pro and Con Review - The American College of Chest PhysiciansQhip NayraÎncă nu există evaluări

- NEJM JW TopGuidelineWatches 2013Document30 paginiNEJM JW TopGuidelineWatches 2013Hoàng TháiÎncă nu există evaluări

- RespimirrorDocument10 paginiRespimirrorsukantaenvÎncă nu există evaluări

- 24 Ashraf Et AlDocument7 pagini24 Ashraf Et AleditorijmrhsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Training and Exercise Treatment of PAD PatientsDocument9 paginiTraining and Exercise Treatment of PAD Patientsnadia shabriÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S2405587515300263 MainDocument8 pagini1 s2.0 S2405587515300263 Maindianaerlita97Încă nu există evaluări

- Preanesthesia IntroductionDocument38 paginiPreanesthesia IntroductionFendy WellenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cytologic and Hematologic Tests Arterial Blood Gases: Medical Background: Chronic Restrictive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument7 paginiCytologic and Hematologic Tests Arterial Blood Gases: Medical Background: Chronic Restrictive Pulmonary Diseasejoanna gurtizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 Minute Walk TestDocument2 pagini6 Minute Walk TestErvina Hesti Utami EliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Inspiratory Muscle Training Using An Electronic Device On Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 paginiEffects of Inspiratory Muscle Training Using An Electronic Device On Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled TrialDaniel Lago BorgesÎncă nu există evaluări

- PAD - KNGF GuidelineDocument16 paginiPAD - KNGF GuidelinepbhqanzghlcuviycmzÎncă nu există evaluări

- EbpDocument14 paginiEbpPaola Marie VenusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise Testing: The 6-Min Walk TestDocument3 paginiExercise Testing: The 6-Min Walk TestDiana HuiculescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Screenig ServicesDocument36 paginiHealth Screenig ServicesTarachand LalwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- One Minute STST Vs 6MWT en EPOCDocument10 paginiOne Minute STST Vs 6MWT en EPOCMaxi BoniniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Inspiratory Muscle Training Using An Electronic Device On Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 paginiEffects of Inspiratory Muscle Training Using An Electronic Device On Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled TrialDaniel Lago BorgesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 1111@sms 13853Document17 pagini10 1111@sms 13853Cintia BeatrizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Table. Applying Class of Recommendation and Level of Evidence To Clinical Strategies, Interventions, Treatments, orDocument14 paginiTable. Applying Class of Recommendation and Level of Evidence To Clinical Strategies, Interventions, Treatments, orJosemd14Încă nu există evaluări

- Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain-2010-Agnew-33-7Document5 paginiContin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain-2010-Agnew-33-7deadbysunriseeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of TENS On PADDocument12 paginiEffect of TENS On PADAyesha SmcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bedside Hemodynamic MonitoringDocument26 paginiBedside Hemodynamic MonitoringBrad F LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Myofascial Release in Patients During The Early Postoperative Period After Revascularisation of Coronary ArteriesDocument13 paginiMyofascial Release in Patients During The Early Postoperative Period After Revascularisation of Coronary Arteriesestefy140399Încă nu există evaluări

- Análisis Del Protocolo de Pasos Adaptados en La Rehabilitación Cardíaca en La Fase HospitalariaDocument10 paginiAnálisis Del Protocolo de Pasos Adaptados en La Rehabilitación Cardíaca en La Fase HospitalariaMary Cielo L CarrilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Article: Evaluation of Pre and Post Bronchodilator Pulmonary Function Test in Fifty Healthy VolunteersDocument8 paginiResearch Article: Evaluation of Pre and Post Bronchodilator Pulmonary Function Test in Fifty Healthy VolunteersEarthjournal PublisherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sonographic Evaluation of The DiaphragmDocument1 paginăSonographic Evaluation of The DiaphragmAngelo LongoniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intermittent Claudication-: ReconstructionDocument10 paginiIntermittent Claudication-: ReconstructionVlad ConstantinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estimating Endurance Shuttle WDocument7 paginiEstimating Endurance Shuttle Wa.rahadianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art Cardiologia IIDocument5 paginiArt Cardiologia IILuis GoncalvesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fast Track Pathways in Colorectal Surgery: Rinaldy Teja SetiawanDocument27 paginiFast Track Pathways in Colorectal Surgery: Rinaldy Teja SetiawanRinaldy T SetiawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance in The Shuttle Walk Test Is Associated With Cardiopulmonary Complications After Lung ResectionsDocument10 paginiPerformance in The Shuttle Walk Test Is Associated With Cardiopulmonary Complications After Lung ResectionsAnonymous Skzf3D2HÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heart 2Document10 paginiHeart 2Nag Mallesh RaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reliability of Gait Performance Tests in Men and Women With Hemiparesis After StrokeDocument8 paginiReliability of Gait Performance Tests in Men and Women With Hemiparesis After StrokeKaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aerobic Exercise Boosts Lung FunctionDocument6 paginiAerobic Exercise Boosts Lung FunctionajenggayatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stress Testing and ECG.. (Poonam Soni)Document14 paginiStress Testing and ECG.. (Poonam Soni)Poonam soniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020-2-ABR - Stability and Predictors of Poor 6-Min Walking Test Performance Over 2 Years in Patients With COPDDocument12 pagini2020-2-ABR - Stability and Predictors of Poor 6-Min Walking Test Performance Over 2 Years in Patients With COPDRodrigo Martín San AgustínÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6-Minute Walk Test in Patients With COPD: Clinical Applications in Pulmonary RehabilitationDocument8 pagini6-Minute Walk Test in Patients With COPD: Clinical Applications in Pulmonary RehabilitationFriendlymeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brown Nathan 2017 The Value and Application of The 6 Minute Walk Test in Idiopathic Pulmonary FibrosisDocument8 paginiBrown Nathan 2017 The Value and Application of The 6 Minute Walk Test in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosisrafaellagirao2002Încă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness of Passive Range of Motion Exercises On Hemodynamic Parameters and Behavioral Pain Intensity Among Adult Mechanically Ventilated PatientsDocument13 paginiEffectiveness of Passive Range of Motion Exercises On Hemodynamic Parameters and Behavioral Pain Intensity Among Adult Mechanically Ventilated PatientsIOSRjournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: Pocket GuidelinesDocument21 paginiThe Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: Pocket GuidelinesRubelyn Joy LazarteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Long Term Impact Preoperator...Document6 paginiLong Term Impact Preoperator...nistormaria492Încă nu există evaluări

- Name-Ashcharya Sachdeva REGISTRATION NO: 11812993 Roll No: 63 Course Code: Pty404 Course Name: Health Promotion and Fitness LaboratoryDocument13 paginiName-Ashcharya Sachdeva REGISTRATION NO: 11812993 Roll No: 63 Course Code: Pty404 Course Name: Health Promotion and Fitness LaboratoryAshcharya SachdevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essentials in Lung TransplantationDe la EverandEssentials in Lung TransplantationAllan R. GlanvilleÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Liver Graft Before Transplantation: Defining Outcome After Liver TransplantationDe la EverandThe Liver Graft Before Transplantation: Defining Outcome After Liver TransplantationXavier VerhelstÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piba Rot 2000Document11 paginiPiba Rot 2000PitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance of A Comprehensive Intraoperative Epiaortic Ultrasonographic ExamDocument9 paginiPerformance of A Comprehensive Intraoperative Epiaortic Ultrasonographic ExamPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Athappan 2013Document11 paginiAthappan 2013PitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance Interpretation and App of Stress EchoDocument21 paginiPerformance Interpretation and App of Stress EchoPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performing A Comprehensive Epicardial Echo ExamDocument11 paginiPerforming A Comprehensive Epicardial Echo ExamPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2008 Cardiac Resynchronization TherapyDocument23 pagini2008 Cardiac Resynchronization TherapyPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use of Carotid US To ID Subclinical Vasc Disease and Eval Disease RiskDocument19 paginiUse of Carotid US To ID Subclinical Vasc Disease and Eval Disease RiskPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Editorial TASC IIDocument2 paginiEditorial TASC IIPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aetiology of Sudden Cardiac Death in SportDocument7 paginiAetiology of Sudden Cardiac Death in SportPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- D2-Excessive Endurance ExerciseDocument9 paginiD2-Excessive Endurance ExerciseJad SoaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excercise Recommendations For Stroke Survivors Ucm - 463998Document1 paginăExcercise Recommendations For Stroke Survivors Ucm - 463998PitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aetiology of Sudden Cardiac Death in SportDocument7 paginiAetiology of Sudden Cardiac Death in SportPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inter Society Consensus For The Management of PAOD TASC II GuidelinesDocument70 paginiInter Society Consensus For The Management of PAOD TASC II GuidelinesPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- HealthyforGood PhysicalActivity Adult Infographic FINAL PDFDocument1 paginăHealthyforGood PhysicalActivity Adult Infographic FINAL PDFLuis DominguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging Volume 17 Issue Suppl 2 2016 (Doi 10.1093 - Ehjci - Jew248.002) Jung, IH. Kurnicka, K. Enache, R. Nagy, AI. Martins, E. Cer - P569Diastolic DyssynDocument26 paginiEuropean Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging Volume 17 Issue Suppl 2 2016 (Doi 10.1093 - Ehjci - Jew248.002) Jung, IH. Kurnicka, K. Enache, R. Nagy, AI. Martins, E. Cer - P569Diastolic DyssynPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise and The HeartDocument25 paginiExercise and The HeartPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Valve Prosthesis-PatientDocument7 paginiImpact of Valve Prosthesis-PatientPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chest X Rays in Pediatric CardiologyDocument35 paginiChest X Rays in Pediatric CardiologyPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cororanary Artery FistulaDocument4 paginiCororanary Artery FistulaPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 1 1 553 2590 PDFDocument3 pagini10 1 1 553 2590 PDFPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Circulation 1990 Berger 401 11Document12 paginiCirculation 1990 Berger 401 11PitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Mba Sari 1Document44 paginiJurnal Mba Sari 1PitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 1152@physiol 00030 2016Document10 pagini10 1152@physiol 00030 2016PitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 508 Hormone Therapy Supplemental 100311Document6 pagini508 Hormone Therapy Supplemental 100311elisasusantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Such As Activation of The Extracellular SignalDocument1 paginăSuch As Activation of The Extracellular SignalPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chest X Rays in Pediatric CardiologyDocument35 paginiChest X Rays in Pediatric CardiologyPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grand Rounds and Case PresentationsDocument22 paginiGrand Rounds and Case PresentationsPitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- GPCR 1Document70 paginiGPCR 1PitoAdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderDocument8 paginiComparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderAnanda Amanda cintaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mot SyllabusDocument30 paginiMot SyllabusShanthoshini Baskaran100% (1)

- Diabetes Management SystemDocument3 paginiDiabetes Management Systembeth2042Încă nu există evaluări

- Research ProposalDocument7 paginiResearch Proposalapi-312374730100% (2)

- What Is GlucosamineDocument5 paginiWhat Is Glucosamineanon-176174Încă nu există evaluări

- REBTDocument12 paginiREBTzero LinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intake Interview QuestionsDocument2 paginiIntake Interview QuestionsjaundersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ooi 150050Document7 paginiOoi 150050MelaNia Elonk ZamroniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antidotes Mechanism of ActionDocument10 paginiAntidotes Mechanism of Actionﻧﻮﺭﻭﻝ ﻋﻠﻴﻨﺎ ﺣﺎﺝ يهيÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hot Pack & Cold PackDocument10 paginiHot Pack & Cold Packm-7946796Încă nu există evaluări

- Geriatopia: A Remediation ScapeDocument4 paginiGeriatopia: A Remediation ScapeJoch CelestialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bone Marrow Donation: How You Can Save a Life in Under an HourDocument4 paginiBone Marrow Donation: How You Can Save a Life in Under an HourazieheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Esophageal ReconstructionDocument98 paginiEsophageal ReconstructionIndera VyasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impulse Control Disorders NOS ExplainedDocument16 paginiImpulse Control Disorders NOS ExplainedimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anterior VitrectomyDocument6 paginiAnterior VitrectomyEdward Alexander Lindo RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Techniques of Feminist TherapyDocument5 paginiTechniques of Feminist TherapyAKANKSHA SUJIT CHANDODE PSYCHOLOGY-CLINICALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clavicle Fracture RehabDocument7 paginiClavicle Fracture Rehabnmmathew mathewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legg-Calve'-Perthes Disease He National Osteonecrosis FoundationDocument5 paginiLegg-Calve'-Perthes Disease He National Osteonecrosis FoundationDanica May Corpuz Comia-EnriquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathophysiology of Chronic Glomerulonephritis: LegendDocument1 paginăPathophysiology of Chronic Glomerulonephritis: LegendGeorich Narciso50% (4)

- 2013DRAFTMEMSProtocols062713 PDFDocument134 pagini2013DRAFTMEMSProtocols062713 PDFMarian Ioan-LucianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reasons For Testing: Air LungsDocument12 paginiReasons For Testing: Air LungsNathyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of Burns in Intensive and Acute CareDocument6 paginiManagement of Burns in Intensive and Acute CareMohd Yanuar SaifudinÎncă nu există evaluări

- TabletsDocument2 paginiTabletsHector De VeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Myocardial InfarctionDocument20 paginiAcute Myocardial InfarctionDavid Christian CalmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case+Study Diabetes PregnancyDocument3 paginiCase+Study Diabetes PregnancyDonna MillerÎncă nu există evaluări

- CCRH Research Strategic VisionDocument3 paginiCCRH Research Strategic VisionMeenu MinuÎncă nu există evaluări