Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Limenaria, A Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos - Stratis Papadopoulos, Dimitra Malamidou

Încărcat de

Sonjce MarcevaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Limenaria, A Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos - Stratis Papadopoulos, Dimitra Malamidou

Încărcat de

Sonjce MarcevaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

ANKARA UNIVERSITY

RESEARCH CENTER FOR MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGY (ANKSAM)

Publication No: 1

Proceedings of the International Symposium

The Aegean in the Neolithic,

Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age

October 13th 19th 1997, Urla - zmir (Turkey)

Edited by

Hayat Erkanal, Harald Hauptmann,

Vasf aholu, Rza Tuncel

Ankara 2008

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at

Thasos

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

Recent archaeological research at Thasos

has been rapidly supplementing our knowledge

on the prehistory of the island (Fig. 1). During

the Late Palaeolithic period, when Thasos was

maybe still part of the continent 1 , we have the

first ascertained human activity at Tzines,

where an important ochre mine has been

excavated 2 . Before the excavation at Limenaria,

Kastri 3 was the only settlement that has offered

secure evidence for Neolithic occupation, while

dim indications came from two other sites: the

acropolis at Limenas 4 and a cave at Skala

Maries 5 . The Early Bronze Age came to light in

small scale trial digs at coastal sites, which

seem to be the principal poles of attraction for

the population in the 3rd mill. The available

evidence comes from the cave of Drakotrypa 6

near Panagia and the promontory of Agios

Antonios 7 . Until recently, the only prehistoric

settlement that has been to some extent

excavated was Skala Sotiros, where impressive

architectural remains of the Early Bronze Age

came to light inducing a great deal of

discussion 8 .

The prehistoric site of Limenaria is

located in Southwest Thasos, under the modern

village, on the east bank of a torrent.

Unfortunately, the largest part of the prehistoric

settlement is today covered by the houses and

the streets of the village (Fig. 2). The 18th

Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical

Antiquities of Kavala has been digging the site

1

2

4

5

6

7

8

Perissoratis et al. 1987, 209; &

1987, . 13; Kraft et al. 1982, 11.

Koukouli-Chrysanthaki et al. 1988, 241-244;

- & Weisgerber 1996, 82-89;

Koukouli-Chrysanthaki & Weisgerber (in press).

-

1992;

(1970) 1971, 16-22; Delt 27-25 (19721980).

BCH 26, 1922, 533.

- 1970, 215-222.

Delt 28, 1973, 447-450.

Delt 26, 1971, 416.

- 1987-1990;

1997.

since 1993. During the years 1993, 1994, 1997,

excavation at the west part of the settlement has

detected deposits dated to the end of the Middle

Neolithic period 9 , while during 1995, 1996

research at the hilltop brought to light

architectural remains of the Early Bronze

Age 10 .

The settlement was founded on a low

rocky hill at the feet of the mountains of

Southwest Thasos. It seems that it was located

ca. 150 m away from the past coastline 11 ,

considering the fact that sea-level in the area

has risen 3 to 4 m since prehistoric times. A

series of sample collecting drills to check

stratigraphy and the origin of raw materials

used in house construction, stone tools

manufacture and pottery, undertook in

collaboration

with

the

Ephorate

of

Palaeoanthropology and Spelaeology at Athens,

has been almost completed.

On the base of the evidence so far

collected, it becomes obvious that we have not

a tell but a settlement horizontally developing

on the hill. Neolithic layers appear on the

hillsides while the Early Bronze Age ones cover

the hilltop where no prior habitation has

existed.

Neolithic Period

On the west slope, excavation developed

horizontally, and an area of ca. 200 m was dug

down to the natural soil. The archaeological

deposit of the Neolithic period is deeper (2,30

m) on the north part of the excavated area,

significantly diminishing (1-1,20 m) to the

south.

Stratigraphy does not offer any indication

on significant changes or hiatus in the

9

10

11

& 1993,

Malamidou 1996.

& 1997.

Kraft et al. 1982.

559-572;

428

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

development of the Neolithic settlement, at

least in the part excavated. Despite the fact that

the natural soil slopes from east to west, the

archaeological layers develop horizontally. Five

stratigraphic compounds, representing several

habitation phases of the end of the Middle

Neolithic can be discerned. Construction

features such as floors, pits and stone benches

are associated with layers I and II. Layer IIa,

25-35 cm thick, is a terrace of reddish argile

upon which these architectural elements were

constructed. Layers III and IV contain clear

traces of constructions and floors of beaten

earth, small pebble and argile, while layer V is

essentially part of the natural soil with few

traces of human activity 12 .

cylindrical with varying diameters and flat

bottoms. Their walls and bottoms are covered

with insulating coating consisting of argiles,

deposits of which have been located near the

settlement. Often the same pits are reused after

being furnished with a new coating. When put

out of use, they are filled with food garbage and

various debris 14 (Photo. 2). In the outer limit of

the inhabited area a series of garbage pits were

located, which simple holes were dug into the

natural soil with no particular shape and no

coating. They contained food remains, mostly

shells, and ash. The fact that such pits are

located exclusively out of the buildings

provides an indication for intentional garbage

disposal outside the settlement limits.

The main building material for the

Neolithic is clay and wood. The houses are

post-framed, but traces of mud brick buildings

are not altogether absent. A series of postholes

in semicircular arrangement were detected in

trench C, possibly the apsidal end of a rather

long house (Fig. 3, left). It is 3 m. wide, but it is

not preserved to its entire length. The house

floors are generally made of reddish or

yellowish clay with small size pebbles, having

been repaired several times.

It is worth mentioning that during the

Middle Neolithic large scale levelling works

took place. For this purpose, terraces made of

solid red soil were created. A first terrace was

constructed immediately on top of the natural

soil, supported to the west by a stone wall

(layer V on the stratigraphy) (Photo. 3). It

aimed at creating a levelled space for the first

installation, thus solving the problem of the

sloping to the west. A second terrace was

uncovered in the upper layers (layer IIa), also

furnished with a supporting wall, built of large

slabs. Such constructions were no doubt result

of team work, which required the collaboration

of a large part of the community 15 .

The floors of hearths and ovens are more

or less well-preserved (Figs. 3: f/E-G & 4:

f1/B). They have a substructure of clay and

pebble-sometimes sherds as well- and an upper

surface of pure clay hardened by fire 13 .

Assemblages of slabstones encased in earth

bearing traces of burning, must be interpreted as

a type of hearth (Fig. 4: f2/B). In one case,

many fish bones were found on top and around

the stones; it may be therefore possible that

roasting on heated stones was applied. Several

sizeable stone assemblages which most of the

times are located near storage pits or hearths

may be interpreted as benches serving food

preparation or household craft activities (Photo.

1).

Storage pits, carefully made, were found

in impressive numbers in the interior of houses

(Fig. 4: s4/D, s4/E-G). They are mostly

The small finds from the Neolithic

deposits of Limenaria offer valuable

information concerning the economy and

ideology of the population. The number of

mortars and grinders is impressive, indicating

that farming held a dominant position.

Archaeobotanical examination has so far

detected the presence of barley, eincorn wheat,

lentil, fig and wild pistache. Though farming

must have been the basic economic strategy, it

seems that the inhabitants complemented their

nutrition with wild fruits. Seashells and fish

14

15

12

13

For the Neolithic Stratigraphy, see: Malamidou 1996,

58.

For relevant examples in Eastern Macedonia, see:

Treuil 1992, 45.

For relevant examples in Eastern Macedonia and

Thrace, see: Treuil 1992, 41; Efstratiou 1993, 36-38

(Proskynites, Makri).

For relevant examples in Northern Greece, see: BCH

116, 1992, 715 (Dikili Tash); & - (1987) 1988, 176

(Mandalo); & 1994, 23

().

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

bones detected in large quantities testify the

close relation of the settlement to the sea, while

the quantities of animal bones, mostly goat, are

also significant.

Polished stone tools are hammers and

axes of various sizes. Chipped tools (Photo. 4)

are represented by small blades and plenty of

flakes and cores. This fact together with the

conservation of remains of exterior surface

(cortex) indicate that some tools were

manufactured inside or near the settlement. As

to the raw material used, the honey-coloured

flint which is very diffused in Thasos 16 , is

dominant, while quarz is also represented in

impressive quantities.

Bone tools -awls, spatulae and needlesare well preserved (Photo. 5). They are

manufactured almost exclusively from the long

bones of small animals, the basic form of the

tool being determined during segmentation.

Secondary work concerns the whole tool and is

particularly careful 17 .

The occupation of the inhabitants with

weaving is established through the discovery of

a small number of biconical spindle whorls,

pierced rounded sherds and loom weights made

of unfired clay. The existence of basketry can

be attested by the imprints of mat on vessel

bottoms. Jewellery are in most cases pierced

shells and Spondylus bracelets. Stone beads and

pendants are scarcer. A pendant has the form of

an animal head with long muzzle and poppedout eyes (Photo. 6). The marble vessels in

shapes imitating clay (a bowl and a

hemispherical tripoid vessel) can be considered

as objects of special social significance, since

they cannot be possessed by everyone.

The scarcity of figurines in the Neolithic

layers of the settlement is a paradox if

compared to the large numbers found in most

sites of Macedonia and Thrace 18 . The upper

part of a female figurine with marked breasts

and navel was found (Fig. 5). It probably

belongs to a type widely diffused in Western

Thrace and Bulgaria towards the end of the

Middle Neolithic 19 . Its main characteristics are

the long neck, cylindrical body, and the swollen

lower body. The total number of figurine

fragments found at Limenaria, both human- and

animal-shaped, is no more than five. Figurines

are altogether absent from the layers of the 3rd

mill., but this is common in the settlements of

East Macedonian and of Northeast Europe in

general 20 .

A series of stone eight-shaped objects

made of marble or gneusian stones (Photo. 7),

known from other Aegean sites such as

Saliagos, are generally interpreted as waistedweights or schematic figurines 21 . Most of them

are of small size, but there are also larger, ca.

0,30 m. in height. An ovoid object with

carefully rounded edges was also found. Any

final conclusion as to the symbolic/ideological

identity of these objects is maybe premature,

but we cannot overlook the fact that there exists

in Thasos a megalithic tradition expressed in

the human-shaped stelae from Skala Sotiros and

Potos.

The burial of a child 3 to 5 years old was

found in a storage pit belonging to the lower

building phases of the Neolithic 22 (Fig. 4: sl/B,

Photo. 8). The skeleton was found lying on his

back with plenty of slabs placed on top and

around it. One of them was placed intentionally

on the chest. The burial had no grave goods.

The skeleton is well preserved and macroscopic

examination revealed the presence of small

holes in both eyeholes suggesting some sort of

bone dissolution process possibly due to

anaemia, the pathology of which cannot be

accurately determined. Also, the deformation of

the teeth enamel may be related to some sort of

malnutrition, something frequently found in

prehistoric populations.

The pottery of the Neolithic layers (Figs.

6 & 7) 23 is examined as a homogenous whole,

19

20

21

22

16

17

18

Peristeri 1989

Christidou 1997, 154.

Marangou 1992, 12; Marangou 1997, 243; Efstratiou

1993, 39.

429

23

& 1994, 44; Todorova &

Vasjov 1993, 198.

Treuil 1983, 248, 410; Marangou 1992, 337-338.

Barber 1991, 98; Evans & Renfrew 1968, 71; Heurtley

1939, 139, 200.

For Neolithic burials in Thrace, see: Agelarakis &

Efstratiou 1996, 11-21.

Pictured Neolithic pottery see in: &

1993, 559-572; BCH 120,3 (1995),

1996, 1282.

430

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

since no important cultural differentiation is

observed in the different habitation phases.

bowls with solid or hollow foot and small

handless cups.

Two types of vessels served the storage

of solid goods:

Incised tripods are found in relative large

numbers (Photo. 11). The decorative motifs on

one of them have been considered to offer proof

of existing relations between the Balkans and

Anatolia during the Early Neolithic 24 .

Nevertheless, there are no other indications for

the existence of that period at Thasos.

a. Pithoi of medium size, no more than

70 cm in height with two vertical handles on the

belly, low neck and wide rim.

b. Handless biconical vessels with

mastoid lugs sprouting at the point of

carination, decorated in the black-topped

technique. They are wide mouthed, have tall

neck and ring shaped base. Traces of burned

organic matter were located in their interior,

resulting from carbonised seeds.

The need of transporting goods was

covered by closed shapes with biconical or

rounded profile, two pairs of facing handles on

one side and a vertical one on the other side, on

top of the shoulder (Photo. 9). The narrow neck,

the position of the handles and the fact that

some of them had no secure base testify to the

fact that they were transport vessels tied on

animals. It should not be however excluded that

they served storage occasionally.

The commonest type of closed vessel among the medium sized vases- is the carinated

jug with wide mouth and the emphasis placed

on the upper part. There is a type with flat ring

base and a tripod one. The vertical handle with

knob or horn lug and rarely an animal or bird

like finial is common to both types. In many

examples, the clay is very thin without

inclusions and forms very thin walls. They bear

rippled or white paint decoration. There exist

also larger jugs with rounded body and distinct

neck decorated with horizontal grooves.

Open deep vessels are mostly represented

by various types of bowls, biconical, with

convex or protruding walls, without handles or

one-handled; also by hemispherical vessels with

one or two handles, with flat base or short legs.

The four-legged bowls (Photo. 10), mostly

large in size, are found in impressive quantities.

Two types can be discerned: without walls with

protruding decorated rim, and two-handled with

vertical walls. There are also small kantharoid

vases usually equipped with one handle

reaching beyond the height of the rim, fruit

Incisions filled with white paste,

impression, finger- or nail-imprints, deep or

shallow grooving, relief decoration and random

incision are preferred for the lesser quality

vases. Rippled decoration is applied on better

quality vessels, fine or medium. The blacktopped technique is common on a large

percentage of medium and fine vessels; it is

often combined with some other type of

decoration. There are only a few examples of

red-topped and grey-topped vessels. The

presence of black-topped ware in the earliest

layers at Limenaria offers supportive argument

for the early appearance of this decorative

technique in Eastern Macedonia, since it is

considered as characteristic of the beginning of

the Late Neolithic 25 .

The only painted ware that can be

securely attributed to this period is the whitish

on black, coming mostly from the upper layers.

It is used, almost exclusively, on the upper part

of the black topped jugs and its repertory

includes spirals, parallel lines and zig-zag. This

pottery ware is known in Central Macedonia

since the early phases of Late Neolithic

(Vasilika II and III) 26 , in the Larisa culture at

Thessaly 27 , and in Aegean sites such as

Saliagos 28 , the Lower Cave at Agios Galas,

Emporio (phases IX-VIII) 29 and Tigani 30 . It is

also found in Chalcolithic sites of Anatolia 31

such as Aphrodisias, Beycesultan, Kusura, Can

Hasan and Mersin. In fact, it is the first time

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

Nikolov 1989, 193.

1992, 102, 197.

1991, 63.

Demoule et al. 1988, 35; Schneider et al. 1991, 29.

Evans & Renfrew 1968, 40.

Hood 1981, 225.

Tlle-Kastenbein 1974, 130, 133.

For detailed discussion, see: Hood 1981, 225-226.

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

that it is found in a certain context in Eastern

Macedonia 32 .

As to the absolute dating of the Neolithic

layers five samples of carbonised material were

examined with the C14 method in

Democritos 33 (Fig. 8). Four of them gave

calibrated values ranging from 5569 to 5255 (in

years BP 6553 64 to 6459 63), that is an

average value a little after the middle of the 6th

mill. (5521-5385, in years BP 6536 41). One

of the samples gave values reaching the

beginning of the 6th mill. (calibrated 5981 to

5678) which are considered too high. The

samples come from the same trench (A),

represent a deposit 70 cm thick (1,65-2,36) and

are compatible with the radiocarbon dates that

we have from the Southeast Balkans.

Only to point out some of the examples

that are close to the settlement at Limenaria, the

beginning of Karanovo III is placed by absolute

values to the middle of the 6th mill. (5450). The

great thickness of the deposits of this phase at

Ezero (2,50 m), alludes that it must certainly

last for about 300-350 years, ending around

5150 to 5100. These dates coincide with the

radiocarbon dates of Vinca A and of Eastern

Macedonian sites. Sitagroi -phase I is dated

between 5500 and 5200, Dikili Tash also offers

calibrated values after the middle of the 6th mill.

(5450-5350, 6800-6700 BP) for the middle

phases of the period, but these should be taken

to be rather high 34 .

The shapes, the decorative practices and

mostly the absolute dating prove that the

settlement at Limenaria was founded towards

the end of the Middle Neolithic period 35 .

Almost all the layers excavated at the

west part of the settlement can be attributed to

32

33

34

35

White-on-dark ware, mentioned as black-topped

variety in Sitagroi and Dikili Tash, has no reference to

that of MN Limenaria.

N.C.S.R. Demokritos, Laboratory of Archaeometry (Y.

Maniatis, G. Fakorellis), Datasets (and intervals),

according to: Stuiver & Pearson 1993, 1-23.

Calibration, according to the Radiocarbon Calibration

Program Rev. 3.0.3c of Quarternary Isotope

Laboratory of Washington University: Stuiver &

Reimer 1993, 215-230.

Boyadziev 1995, 165; Renfrew et al. 1986, 173; Treuil

1992, 34; 1997, 266.

1992, 107.

431

this period which is represented in the wider

area of the Southeast Balkans by Sitagroi I-II,

Dimitra I II, Paradimi I-III, Makri I-II, Dikili

Tash I and Karanovo III 36 . Though cultural

affinities with Thessaly and the Aegean are not

altogether absent, the dominant characteristics

of the settlement connect it closely with the area

of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace.

The presence of later phases of the

Neolithic must be considered certain at

Limenaria. Among the surface finds, sherds of

the Late Neolithic I painted wares,

Akropotamos style for example, which were

widely diffused in Eastern Macedonia, are

indeed found. The same is true for the Late

Neolithic II wares, such as the graphite-painted

and the black on red 37 . However, the presence

of these ceramic traditions is not attested in the

layers excavated.

Early Bronze Age

The Early Bronze Age is represented at

Limenaria by an excavated area of only 70

square meters. At least three building phases of

the period were located on the hilltop. The first

habitation layer (Fig. 9) consists of a floor made

of pebble, sherds and solid soil, maybe part of a

road or a yard, associated with an hearth and a

large garbage pit (Photo. 12), all being limited

by a wall to the north. This phase is founded on

the natural ground in the south part of the

excavated area, and on a fill of loose soil,

stones and abundant Neolithic pottery in the

north part. It seems, therefore, that it was

necessary to arrange the natural ground by

creating artificial fills and by levelling in order

to prepare a solid base for construction. For this

purpose, soil was transferred from areas of the

settlement with Neolithic deposits.

A layer, 0,30 to 0,50 m thick, consisting

of brown argile with pebbles, covers this phase

as well. This lead us to believe that filling and

levelling in order to re-use the same area took

place after the destruction of the first habitation

phase. Pottery characteristic of the EB II period

in Eastern Macedonia (Photo. 13), with incised

and impressed decoration with white infill, was

36

37

Keighley 1986, 363.

1992, 189.

432

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

traced in the fill 38 . It is interesting to note that

the Neolithic ceramic material of this layer must

belong to the latest phases of the Late Neolithic.

It is characterised by the limited use of graphite,

in rectilinear patterns only, by the pink or

whitish paint on dark ground in motifs imitating

those of the graphite, and by the addition of

crusted paints, purple and pink (Photo. 14). The

dating of these wares to the first half of the 4th

mill. in Thasos 39 , is under discussion and we

cite it here reluctantly.

The later habitation phase (Fig. l0) which

lies above the second fill has features which are

difficult to interpret and find no parallels in the

Aegean world and the Balkans. To this phase

belongs a wide slightly curving wall, built with

large pebbles, uncovered in 5 m length. A

group of oblong stones, fixed vertically in rows,

on a pebble floor was discovered to the area

east of the wall (Photo. 15). Fifteen stones of

this type were found in situ while 3 or 4 were

moved due to the extended disturbance. They

protrude 0,30 to 0,40 m from the pebble floor

level (Photo. 16).

The larger stones reach 0,70 m in height,

0,35 m in width, and are 0,20 m thick. Traces of

a rough workmanship of the surface can be

observed on some of them. A row of flag stones

to the north of the excavated area probably

belongs to a later arrangement of the area. An

egg-shaped flat stone, measuring 0,50 to 0,63 m

and 0,16 m width, bearing 30 small cavities

along its perimeter around a central one on the

top surface (Photo. 17), was discovered to the

west side of this pebble floor close to the wall.

Its shape recalls the so-called offering tables

well-known in the Southern Aegean.

The understanding of this later habitation

phase at Limenaria is difficult mainly for two

reasons: The first one is the absence of

sufficient stratigraphic context which is due to

the fact that this phase lies immediately under

the surface layer which was very disturbed. The

second reason, mentioned above, is the form of

the structures which have no parallels in the

surrounding area. It seems that what we have is

an open-air area -hypothesis strengthened by

the lack of finds- the identity of which,

utilitarian or symbolic, can not be, for the time

being, ascertained.

One can insists on the ideological /

symbolic character of the find, offering the

megalithic monuments of the Western

Mediterranean as the closest parallel. There,

stones, the so-called menhir, vertically fixed on

the ground in rows, circles or other formations

are usually associated with funerary or cult

structures. Rows of vertical stones, often

incorporating large numbers of menhirs, usually

of large dimensions, in some cases however

smaller than 0,50 m. are found in Corse 40 ,

where Mediterranean megalithic tradition is

the rule. Such structures are usually located

close to passages, springs or serve as boundary

marks of agricultural, husbandry-oriented, or

even ceremonial grounds. In Sardinia 41 ,

towards the end of the Chalcolithic period,

shortly before the middle of the 3rd mill., slab

covered areas surrounded with menhirs, built on

top of terraces, can be found near the external

limits of settlements or, in rare cases, among the

houses of an inhabited area. Those structures

are usually connected with ceremonial

activities, as well.

Also, we cannot overlook the megalithic

tradition of Thasos itself, as this is expressed in

the human-shaped stelae from Skala Sotiros and

Potos 42 . These were not found in their original

position; the ones at Skala Sotiros were built in

the settlement wall, a use that certainly annulled

their initial purpose, while the stele from Potos

is a chance find. As related artefacts from the

wider Aegean area we may cite the stelae of

Troy I 43 and Argissa 44 . The baitylos in the area

513 of Poliochni Red 45 has been considered a

ceremonial object.

On the other hand, we may not exclude

the possibility that the find may have had a

utilitarian purpose that may coexist with the

40

41

42

43

38

39

1997, 199.

Demoule 1993, 383.

44

45

Camps 1994, 68.

Webster 1999, 53.

- (1987) 1988, 396; (1989) 1992, 512.

Korfmann & Mannsperger 1997, 53.

Biesantz 1959, Fig. 1-2.

Poliochni 1997, 105.

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

symbolic one. To this corroborate the following

observations:

a. The vertical stones of Limenaria bear

no trace of special treatment on their surfaces.

Therefore, they do not belong to the type of the

anthropomorphic stelae.

b. The stones that were preserved intact

are of the same height. Even if this indicate an

intentional levelling, it remains difficult to

accept that it supported some sort of

construction, because of the pointed tops of the

stones.

It is worth discussing the presence of the

offering table, an object the function of which

in the area of the wider Aegean is also under

discussion. It would be preferable to term such

objects stones with cavities (pierre

cupules) rather than offering tables or

kernoi, a terminology which was established

in analogy to the Eleusinian kernoi of the

historical periods during the early discussions

on the subject 46 . These objects are usually made

of limestone and bear a large number, 30 to 40

of cavities. Despite the fact that each one of the

known examples has its own morphological

features, it seems that all follow a common

prototype, maybe connected with a Middle

Neolithic seal type of Thessaly 47 .

They have been interpreted as ceremonial

objects, serving the acts of offering and

libation, and they have been connected with the

female deity of the Minoan religion or the

Rhea-Kybele 48 . It has been however proposed

by some, like Evans and Effenterre 49 , that they

were simple games. Most examples come from

the palace at Malia 50 . They were discovered not

only in the central court and the west wing of

the palace, but also in the Chryssolakkos

cemetery. They are very rare in North Aegean:

a large flagstone with cavities in assymetrical

arrangement was used in one of the bastions of

gate B at Skala Sotiros 51 . A related find,

interpreted as a game-table, was found in the

paved street 12l during the old excavations at

Poliochni 52 . Objects of such type seem to

continue to be used in the area of the North

Aegean during the historical period 53 .

During the EB II period, the settlement at

Skala Sotiros 54 , gives the impression of a small

fortified settlement, not larger than 1,500 m,

enclosed in a wall built by flagstones, among

which were embedded human-shaped stelae.

Here, the presence of semicircular bastions and

antae, which reinforce the wall from the inside,

as well as the fishbone wall construction permit

comparisons with Aegean settlements such as

Kastri in Syros, Panormos, Kynthos, Aegina,

Lerna, Liman Tepe and Troy 55 , even with

West-Mediterrannean sites at Spain, Sicily and

Corse 56 . The use of large flagstones as

orthostates mostly in the area of the gates is

also reminiscent of Troy.

If we add to this, the picture emerging

from Limenaria, no matter how fragmentary,

we reach the conclusion that during this period

Thasos is closer to the Aegean architectural

tradition than to that of Macedonia and Thrace,

where Neolithic architectural practices continue

to be in use, with clay and wood as dominant

building material 57 . This idea is congruent with

the renewed interest to settle coastal sites

located mostly to the south part of the island.

The finds from the excavated area of the

Bronze Age settlement are limited, and their

date under discussion due to the extended fills

mentioned above. But, we can briefly point

that:

The technology of chipped tools offers

indications of a decline in the layers of the 3rd

mill. a fact observed in other contemporary

North Greek sites 58 . Advance in hunting

technology is marked by the adoption of arrowheads, a widely diffused innovation during the

3rd mill. 59 . Obsidian in small quantities reaches

52

53

46

47

48

49

50

51

Chapouthier 1928, 309.

Papathanassopoulos 1996, 333, 334; 1992, 85.

Pelon 1988, 31.

Evans 1930, 390-395; Van Effenterre 1955, 541-548.

Pelon 1992, 62.

-, 1988, 402, Fig. 7.

433

54

55

56

57

58

59

Poliochni 1997, 94, Fig. 1.

(1989) 1992, 220.

- 1987-1990.

Barber 1987, 53; 1984, 77, 85; Erkanal 1997;

Korfmann & Mannsperger 1997.

Chapman 1990, 78; Malone et al. 1994, 173.

Malamidou 1997, 332.

Treuil 1992, n. 33, 81, 96; Fotiadis 1985, 87.

Treuil 1992, n. 20, 148.

434

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

the settlement during its whole life-span. The

study of samples from Limenaria and Skala

Sotiros under the microscope, as part of the

Democritus Obsidian Analysis Program 60

proved that these tools came from Melos and,

more precisely, the vast majority came from

Adamas.

The large number of spindle whorls in

the Bronze Age layers indicates that weaving

must have been an activity that has taken off

during this period. That intensification,

however, may have already manifested in the

4th mill., if we take a number of these spindle

whorls to belong to the earlier material of the

intentional fill.

A large number of crude iron lumps was

found in the excavated area. Such material is

abundant in the area around the settlement and

appears in the same abundant quantities in

layers of the Middle Neolithic. Traces of a

metallurgical activity, copper slags and lumps,

were also discovered but we consider their

discussion here premature 61 .

We do not have any radiocarbon dates

yet from deposits of the Bronze Age, and the

relevant ceramic material is limited. Incised,

relief and impressed decoration, including stab

and drag, usually with added white paste in the

grooves, which is widespread in Eastern

Macedonia 62 , has been located in surface and

excavation contexts at Limenaria, but it is not

clear if it was included in the habitation layers

excavated. The presence of dark pottery

represented by bowls and open vessels with

convex walls (Photo. 18), handless or onehandled, can be safely attributed to these

building phases. These phases must be

contemporary to the earliest phase at Skala

Sotiros, Sitagroi Va, Dikili Tash IIIB,

Pentapolis II and Troy I and are dated to the

first half of the 3rd mill., according to the

radiocarbon dates known so far from Eastern

Macedonia 63 .

60

61

62

63

N.C.S.R. Demokritos, Laboratory of Archaeometry (V.

Kilikoglou, A. Moundrea-Agrafioti, A. Kyritsi).

N.C.S.R. Demokritos, Laboratory of Archaeometry (I.

Bassiakos).

1997, 199.

- (1990) 1993, 535.

Calibrated dates between 3100 and 2700

are considered valid for Sitargoi Va, between

2700 and 2200 for Sitagroi Vb, between 2550

and 2350 for Pentapolis II, and between 2590

and 1750 for Skala Sotiros. The date of the

second phase of the Bronze Age sector -that is

the stone-paved area wit menhirs- can be even

later, if we consider as a certain chronological

kriterion the presence of typical EB II pottery in

the levelling fill just under the terrace. Also, if

the presence of the stone of cavities is taken

as a testimony of cultural relations connecting

Limenaria with the South Aegean, then a date

after the beginning of the 2nd mill. must not be

out of the question. This idea is dictated by the

lowest of the calibrated dates of Sitagroi and

Skala Sotiros.

STRATIS PAPADOPOULOS &

DIMITRA MALAMIDOU

18th Ephorate of Prehistoric and

Classical Antiquities,

Kavala, GREECE

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

435

Bibliography:

Agelarakis, A. & N. Efstratiou 1996, Skeletal Remains from the Neolithic Site of Nea Makri-Thrace. A Preliminary

Report, in: Archaeometrical and Archaeological Research in Macedonia and Thrace. Thessaloniki, 11-21.

, I. 1992, : . .

Barber, E.J.W. 1991, Prehistoric Textiles. A Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Princeton.

Barber, R.L.N. 1987, The Cyclades in the Bronze Age. London.

Biesantz, H. 1959, Die Ausgrabung bei der Soufli-Magula, AA 74, 1959, 56-74.

Boyadziev, Y.D. 1995, Chronology of Prehistoric Cultures in Bulgaria, in: Bailey, D.W. & I. Panayotov (eds.) 1995,

Prehistoric Bulgaria, Monographs in World Archaeology n. 22, 149-191.

Camps, G. 1994, Prhistoire d'une le. Les origines de la Corse. Paris.

Cesari, J. 1994, Corse des origines, Guides Archologiques de la France. Paris.

Chapman, R. 1990, Emerging Complexity. The Later Prehistory of South-East Spain, Iberia and the West Mediterranean,

New Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge.

Chapouthier, F. 1928, Une table offrandes au palais de Malia, BCH 52, 309 ff.

Christidou, R. 1997, Dimitra, Bone-working, in: , .. 1997, , -.

. 56, .

Demoule, J.-P. 1993, Nolithique et Chalcolithique de Macdoine: Un etat des questions, V.1, 240,

383 ff.

Demoule, J.-P., K. Gallis & L. Manolakakis 1988, Transition entre les cultures neolithiques de Sesklo et de Dimini: Les

categories ceramiques, BCH 112, 1-58.

Efstratiou, N. 1993, New Prehistoric Finds from Western Thrace, Greece, Anatolica 19, 33-46.

, N. & . 1994, . 1988-1993. .

Erkanal, H. 1997, Archaeological Researches at Liman Tepe. Municipality of Urla.

Evans, A.J. 1930, The Palace of Minos at Knossos, III. London.

Evans, J. D. & C. Renfrew 1968, Excavations at Saliagos near Antiparos. London.

Fotiadis, M. 1985, Economy, Ecology and Settlement among Sub-sistence Farmers in the Serres Basin, Northeastern

Greece: 5000-1000 B.C., Ph.D. University of California, Ann Arbor. Michigan.

, .. 1991, , , . 117,

.

, .. 1997, , . . 56, .

Heurtley, W.A. 1939, Prehistoric Macedonia. An Archaeological Reconnaissance of Greek Macedonia (West of the Struma)

in the Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages. Cambridge.

Hood, S. 1981, Excavations in Chios 1938-1955. Prehistoric Emporio and Ayio Gala, vol. I, B.S.A. Suppl. Vol. N. 15.

London.

Keighley, J.M. 1986, The Pottery of Phases I and II, in: Renfrew, C. et al. (eds.) 1986, Excavations at Sitagroi. A

Prehistoric Village in Northeastern Greece, vol. 1, Monumenta Archaeologica 13. Los Angeles.

, N. 1984, .

. .

Korfmann, M. & D. Mannsperger 1997, A Guide to Troia. Istanbul.

-, . 1970, , AA , 215-222.

-, . 1971, , phem (1970), 16-22.

-, . 1987-1990, AErgoMak 1-4.

-, . 1988, , AErgoMak 1

(1987), 389-406.

-, . 1992, , AErgoMak 3

(1989), 507-520.

-, . 1993, 1990, AErgoMak 4 (1990), 531-545.

-, . 1992, . ,

, . 45, .

436

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

Koukouli-Chrysanthaki, Ch., G. Weisgerber, G. Gialoglou & M. Vavelidis 1988, Prhistorischer und junger Bergbau

auf Eisenpigmente auf Thasos, in: Wagner, G.A & G. Weisgerber (eds.) 1988, Antike Edel- und

Buntmetallgewinnung auf Thasos, Der Anschnitt 6, 241-244.

-, . & G. Weisgerber 1996, , 60, 82-89.

Koukouli-Chrysanthaki, Ch., G. Weisgerber (in press), Ochre Mines on Thasos, in: Koukouli-Chrysanthaki, Ch., A.

Mller & S. Papadopoulos (eds.), Thasos: Matires Premires et Technologie de la Prhistoire nos jours, .F.A.

Kraft, J.C., I. Kayan & O. Erol 1982, Geology and Palaeogeographic Reconstructions of the Vicinity of Troy, in: Rapp,

G. & J.A. Gifford (eds.) 1982, Troy. The Archaeological Geology, Suppl. Monograph 4. Cincinnati.

Malamidou, D. 1996, L habitat et l architecture du Neolithique Moyen en Macedoine Orientale. Les cas de Limenaria

(Thasos), Memoire de DEA-Universit de Paris I. Paris.

Malamidou, D. 1997, Eastern Macedonia During the Early Bronze Age, in: Doumas, Ch. & V. La Rosa (eds.) 1997,

. , 329-343.

, . & . 1993, , AErgoMak 7,

559-572.

, . & . 1997, : , AErgoMak

11, 585-596.

Malone, C., S. Stoddart & R. Whitehouse 1994, The Bronze Age of Southern Italy, Sicily and Malta c. 2000-800 B.C.,

in: Mathers, C. & S. Stoddart (eds.) 1994, Development and Decline in the Mediterranean Bronze Age. Sheffield,

167-194.

Marangou, C. 1992, : Figurines et miniatures du Neolithique Recent et du Bronze Ancien en Grce, BAR

International Series 576. Oxford.

Marangou, C. 1997, Neolithic Micrography: Miniature Modelling at Dimitra, in: , .. 1997, 227-266.

Nikolov, V. 1989, Das Flutal der Struma als Teil der Strae von Anatolien nach Mitteleuropa, in: Neolithic of

Southeastern Europe and its Near Eastern Connections 1989, Varia Arch. Hungarica II. Budapest, 191-200.

, . 1997, N .

, Ph. D. University of Thessaloniki. Thessaloniki.

-, . & . - 1988, , AErgoMak 1, (1987),

173-177.

Papathanassopoulos, G.A. (ed.) 1996, Neolithic Culture in Greece, N.P.Goulandris Foundation- Museum of Cycladic Art.

Athens.

Pelon, O. 1988, L'autel minoen sur le site de Malia, egaeum 2, 31-46.

Pelon, O. 1992, Quide de Malia: Le palais et la ncropole de Chryssolakkos, E.F.A. Athens.

Perissoratis, C., S.A. Moorby, C. Papavasiliou, D.S. Cronan, F. Angelopoulos, F. Sakellariadou & D. Mitropoulos

1987, The Geology and Geochemistry of the Surficial Sediments of Thraki, Northern Greece, Marine Geology 74,

209-224.

, . & . 1987, .

Peristeri, K. 1989, Thasos prhistorique partir de lindustrie lithique taill de Skala Sotiros, Memoire de DEA Paris I,

Paris.

-, A. 1992, , in:

. .. , , . 48,

, 83-90.

Poliochni, On smoke-shroud Lemnos. An Early Bronze Age Centre in the North Aegean 1997, Ministry of Aegean-20th

EPKA-S.A.I.A. Athens.

Renfrew, C., M. Gimbutas & E.S. Elster (eds.) 1986, Excavations at Sitagroi. A Prehistoric Village in Northeastern

Greece, vol. 1, Monumenta Archaeologica 13. Los Angeles.

Schneider, G., H. Knoll, K. Gallis & J.-P. Demoule 1991, Transition entre les cultures neolithiques de Sesklo et de

Dimini: Recherches mineralogiques, chimiques et technologiques sur les ceramiques et les argiles, BCH 115, 1-64.

, . 1992, . , AErgoMak 3 (1989), 215-225.

Stuiver, M. & G.W. Pearson 1993, High-precision Bidecadal Calibration of the Radiocarbon Time Scale, AD 1950-500

BC and 2500-6000 BC, Radiocarbon 35.1, 1-23.

Stuiver, M. & P.J. Reimer 1993, Extended

Radiocarbon, 35.1, 215-230.

14

C Data Base and Revised Calib 3.0

14

C Age Calibration Program,

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

437

Todorova, H. & I. Vasjov 1993, The Neolithic in Bulgaria (in Bulgarian). Sofia.

Tlle-Kastenbein, R. 1974, Samos XIV: Das Kastro Tigani. Bonn.

Treuil, R. 1983, Le Nolithique et le Bronze Ancient Egens. Les problmes stratigraphiques et chronologiques, les

techniques, les hommes, Paris.

Treuil, R. (ed.) 1992, Dikili Tash. Village prhistorique de Macdoine Orientale: Fouilles de J. Deshayes (1961-1975),

BCH Suppleent 24.

Van Effenterre, H. 1955, Cupules et naumachie, BCH 79, 541-548.

Webster, G.S. 1999, A Prehistory of Sardinia 2300-500 BC, Monographs in Mediterranean Archaeology, n. 5. Sheffield.

List of Illustrations:

Figures:

Fig. 1: Thasos: The prehistoric sites

Fig. 2: Limenaria: The Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Sectors.

Fig. 3: NL Sector: Habitation layer of 1,35-1,45 m.

Fig. 4: NL Sector: Habitation layer of 2,05 m.

Fig. 5: Middle Neolithic figurine

Fig. 6: Middle Neolithic pottery

Fig. 7: Middle Neolithic bowls

Fig. 8: Calibrated Radiocarbon Dates of Middle Neolithic layers

Fig. 9: EB Sector:1st haditation layer

Fig. 10: EB Sector: 2nd habitation layer

Photos:

Photo. 1: NL Sector: Storage pit and stone assemblage

Photo. 2: NL Sector: Storage pit filled with shattered vases

Photo. 3: NL Sector: Stone wall supporting a terrace

Photo. 4: Chipped tools

Photo. 5: Bone tools

Photo. 6: Stone pendant

Photo. 7: Stone eight-shaped artifacts

Photo. 8: NL sector: The burial of a child

Photo. 9: Transport vase

Photo. 10: Four-legged bowl

Photo. 11: Incised Tripods

Photo. 12: EB Sector,1st habitation layer: hearth and garbage pit

Photo. 13: EB pottery

Photo. 14: LN pottery

Photo. I5: EB Sector, 2nd habitation layer: The pebble floor

Photo. 16: EB Sector, 2nd habitation layer: The menhirs

Photo. 17: Stone with cavities

Photo. 18: Vessel belonging to the 1st habitation layer of EB

438

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

439

440

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

441

442

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

443

444

Stratis PAPADOPOULOS & Dimitra MALAMIDOU

Limenaria, a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos

445

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Antikythera Shipwreck ReconsideredDocument47 paginiThe Antikythera Shipwreck ReconsideredJoanna DrugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Walking Guide To 42 Greek IslandsDocument297 paginiWalking Guide To 42 Greek Islandsorg25grÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient Macedonia IVDocument680 paginiAncient Macedonia IVViktor LazarevskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- On The Names of Thracia and Eastern Macedonia - Nade ProevaDocument9 paginiOn The Names of Thracia and Eastern Macedonia - Nade ProevaSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- The Macedonians According To Ancient Greek Sources - Dimitri MichalopoulosDocument6 paginiThe Macedonians According To Ancient Greek Sources - Dimitri MichalopoulosSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- Aegean Archaeology GreeceDocument370 paginiAegean Archaeology GreeceHarizica100% (1)

- The Monastery of Treskavec - Aleksandar VasilevskiDocument35 paginiThe Monastery of Treskavec - Aleksandar VasilevskiSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Aging Report ViennaDocument107 paginiAging Report ViennaEdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALEKSHIN, V. 1983 - Burial Customs As An Archaeological SourceDocument14 paginiALEKSHIN, V. 1983 - Burial Customs As An Archaeological SourceJesus Pie100% (1)

- Funerary Practices in The Early Iron Age in Macedonia - Aleksandra Papazovska SanevDocument14 paginiFunerary Practices in The Early Iron Age in Macedonia - Aleksandra Papazovska SanevSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Ancient Genomic Time Transect From The Central Asian Steppe Unravels The History of The ScythiansDocument15 paginiAncient Genomic Time Transect From The Central Asian Steppe Unravels The History of The ScythiansErwin SchrödringerÎncă nu există evaluări

- A032a02 PDFDocument256 paginiA032a02 PDFGrendel MictlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Church of Saint George at Kurbinovo - Elizabeta DimitrovaDocument32 paginiThe Church of Saint George at Kurbinovo - Elizabeta DimitrovaSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- The Church of The Holy Mother of God at The Village of Matejche - Elizabeta DimitrovaDocument32 paginiThe Church of The Holy Mother of God at The Village of Matejche - Elizabeta DimitrovaSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- Places in Between: The Archaeology of Social, Cultural and Geographical Borders and BorderlandsDe la EverandPlaces in Between: The Archaeology of Social, Cultural and Geographical Borders and BorderlandsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bronze Age Tumuli and Grave Circles in GREEKDocument10 paginiBronze Age Tumuli and Grave Circles in GREEKUmut DoğanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chronology of Linear B DocumentsDocument12 paginiChronology of Linear B Documentsraissadt8490Încă nu există evaluări

- Experimentation and Interpretation: the Use of Experimental Archaeology in the Study of the PastDe la EverandExperimentation and Interpretation: the Use of Experimental Archaeology in the Study of the PastÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alberti 2009 Archaeologies of CultDocument31 paginiAlberti 2009 Archaeologies of CultGeorgiosXasiotisÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASCSA - Amphoras and The Ancient Wine Trade, AgoraDocument35 paginiASCSA - Amphoras and The Ancient Wine Trade, Agoraolgaelp100% (1)

- Domestication and Early History of The Horse: Marsha A. LevineDocument18 paginiDomestication and Early History of The Horse: Marsha A. LevineStoie GabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geoarchaeological Studies in The Sboryanovo National Reserve (North-East Bulgaria)Document7 paginiGeoarchaeological Studies in The Sboryanovo National Reserve (North-East Bulgaria)Anamaria Ștefania BalașÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sara A. Immerwahr - The Neolithic and Bronze Ages Athenian AgoraDocument396 paginiSara A. Immerwahr - The Neolithic and Bronze Ages Athenian AgoradavayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enclosing The Past - Zbornik PDFDocument176 paginiEnclosing The Past - Zbornik PDFTino TomasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Battle of Chaeronea: The Culmination of Philip II of Macedon's Grand Strategy - Kathleen GulerDocument11 paginiThe Battle of Chaeronea: The Culmination of Philip II of Macedon's Grand Strategy - Kathleen GulerSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- Eaaw1391 FullDocument9 paginiEaaw1391 Fulldavid99887Încă nu există evaluări

- The Royal Court in Ancient Macedonia: The Evidence For Royal Tombs - Olga PalagiaDocument23 paginiThe Royal Court in Ancient Macedonia: The Evidence For Royal Tombs - Olga PalagiaSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Early Christian Wall Paintings from the Episcopal Basilica in Stobi: Exhibition catalogue - Elizabeta Dimitrova, Silvana Blaževska, Miško ТutkovskiDocument48 paginiEarly Christian Wall Paintings from the Episcopal Basilica in Stobi: Exhibition catalogue - Elizabeta Dimitrova, Silvana Blaževska, Miško ТutkovskiSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- Eternity PDFDocument29 paginiEternity PDFΑγορίτσα Τσέλιγκα ΑντουράκηÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient DNA, Strontium IsotopesDocument6 paginiAncient DNA, Strontium IsotopesPetar B. BogunovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chrysoula Saatsoglou-Paliadeli - Queenly - Appearances - at - Vergina-Aegae PDFDocument18 paginiChrysoula Saatsoglou-Paliadeli - Queenly - Appearances - at - Vergina-Aegae PDFhioniamÎncă nu există evaluări

- BINFORD - Mobility, Housing, and Environment, A Comparative StudyDocument35 paginiBINFORD - Mobility, Housing, and Environment, A Comparative StudyExakt NeutralÎncă nu există evaluări

- Choyke, Schibler - Prehistoric Bone Tools and The Archaeozoological PerspectiveDocument15 paginiChoyke, Schibler - Prehistoric Bone Tools and The Archaeozoological PerspectiveRanko ManojlovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Excavation of An Early Bronze Age Cemetery at Barns Farm, Dalgety, Fife. Proc Soc Antiqs Scot 112 (1982) : 48-141.Document103 paginiThe Excavation of An Early Bronze Age Cemetery at Barns Farm, Dalgety, Fife. Proc Soc Antiqs Scot 112 (1982) : 48-141.Trevor Watkins100% (1)

- Tell Communities and Wetlands in Neolithic Pelagonia, Republic of Macedonia - Goce NaumovDocument16 paginiTell Communities and Wetlands in Neolithic Pelagonia, Republic of Macedonia - Goce NaumovSonjce Marceva100% (3)

- Tell Communities and Wetlands in Neolithic Pelagonia, Republic of Macedonia - Goce NaumovDocument16 paginiTell Communities and Wetlands in Neolithic Pelagonia, Republic of Macedonia - Goce NaumovSonjce Marceva100% (3)

- Early Bronze Age Metallurgy in The North-East Aegean: January 2003Document31 paginiEarly Bronze Age Metallurgy in The North-East Aegean: January 2003Lara GadžunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Haggis Lakkos 2012Document44 paginiHaggis Lakkos 2012Alexandros KastanakisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Butrint 6: Excavations on the Vrina Plain: Volume 3 - The Roman and late Antique pottery from the Vrina Plain excavationsDe la EverandButrint 6: Excavations on the Vrina Plain: Volume 3 - The Roman and late Antique pottery from the Vrina Plain excavationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- JWP - 1989 - 3!2!199-233 Intentional Human Burial M-Paleolithic Beginnings SmirnovDocument35 paginiJWP - 1989 - 3!2!199-233 Intentional Human Burial M-Paleolithic Beginnings SmirnovRenzo Lui Urbisagastegui ApazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burials Upper Mantaro Norconck & OwenDocument37 paginiBurials Upper Mantaro Norconck & OwenManuel Fernando Perales MunguíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drama of Death in A Minoan Temple. National Geographic, February 1981Document5 paginiDrama of Death in A Minoan Temple. National Geographic, February 1981Angeles García EsparcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kogalniceanu - Human RemainsDocument46 paginiKogalniceanu - Human RemainsRaluca KogalniceanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 118041-CT-RHA TANCA DEWANA-JURNAL-compressed PDFDocument10 pagini118041-CT-RHA TANCA DEWANA-JURNAL-compressed PDFtancaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community With The Ancestors. Ceremonies and Social Memory in The Middle Formative at Chiripa, BoliviaDocument28 paginiCommunity With The Ancestors. Ceremonies and Social Memory in The Middle Formative at Chiripa, BoliviaSetsuna NicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dusan Boric, First Households in European PrehistoryDocument34 paginiDusan Boric, First Households in European PrehistoryMilena VasiljevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- For The Temples For The Burial Chambers.Document46 paginiFor The Temples For The Burial Chambers.Antonio J. MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acta 5Document221 paginiActa 5Bugy BuggyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cameron, A. - The Exposure of Children and Greek Ethics - CR, 46, 3 - 1932 - 105-114Document11 paginiCameron, A. - The Exposure of Children and Greek Ethics - CR, 46, 3 - 1932 - 105-114the gatheringÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jan Turek Ed. Abstracts 19th Annual Meet PDFDocument468 paginiJan Turek Ed. Abstracts 19th Annual Meet PDFИванова Светлана100% (2)

- 2008 Meso-Europe Bonsall PDFDocument122 pagini2008 Meso-Europe Bonsall PDFNoti Gautier100% (1)

- Çadır Höyük - Ancient ZippalandaDocument97 paginiÇadır Höyük - Ancient ZippalandaRon GornyÎncă nu există evaluări

- SpierCole EgyptClassicalWorldDocument187 paginiSpierCole EgyptClassicalWorldGeorgiana GÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palaima, Thomas G. Sacrificial Feasting in The Linear B Documents.Document31 paginiPalaima, Thomas G. Sacrificial Feasting in The Linear B Documents.Yuki Amaterasu100% (1)

- Archaeological Field DrawingDocument5 paginiArchaeological Field DrawingangelhydÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbookofasiami 01 GreauoftDocument376 paginiHandbookofasiami 01 GreauoftCathy SweetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cave Paintings Are A Type ofDocument4 paginiCave Paintings Are A Type ofJordan MosesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valeria Fol - Rock-Cut MonumentsDocument10 paginiValeria Fol - Rock-Cut MonumentsAdriano PiantellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BPS 8 Шмит моно PDFDocument357 paginiBPS 8 Шмит моно PDFИванова СветланаÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perles 2004 - The Early Neolithic in GreeceDocument2 paginiPerles 2004 - The Early Neolithic in GreeceCiprian CretuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mycenaean Burial CustomsDocument8 paginiMycenaean Burial CustomsVivienne Gae CallenderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dietrich PDFDocument18 paginiDietrich PDFc_samuel_johnstonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Rebecca Saunders, Dr. Rebecca Saunders, Christopher T. Hays, Christopher T. Hays, Richard A. Weinstein, Anthony L. Ortmann, Kenneth E. Sassaman, James B. Stoltman, Tristram R. Kidder, Jon L. Gibson, Prentice Thom.pdfDocument294 paginiDr. Rebecca Saunders, Dr. Rebecca Saunders, Christopher T. Hays, Christopher T. Hays, Richard A. Weinstein, Anthony L. Ortmann, Kenneth E. Sassaman, James B. Stoltman, Tristram R. Kidder, Jon L. Gibson, Prentice Thom.pdfhotdog10100% (1)

- Sir Arthur EvansDocument2 paginiSir Arthur EvansDanielsBarclay100% (1)

- Lumsden - Narrative Art and Empire - The Throneroom of Assurnasirpal IIDocument28 paginiLumsden - Narrative Art and Empire - The Throneroom of Assurnasirpal IIAnthony SooHooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gimbutas Battle Axe or Cult AxeDocument5 paginiGimbutas Battle Axe or Cult AxeMilijan Čombe BrankovićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chalcatzingo Monument 34Document9 paginiChalcatzingo Monument 34thule89Încă nu există evaluări

- Corinth Vol 01 NR 4 1954 The South StoaDocument287 paginiCorinth Vol 01 NR 4 1954 The South StoaOzan GümeliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Armenian JughaDocument98 paginiArmenian JughaAdi_am100% (4)

- Carved Stone BallsDocument6 paginiCarved Stone Ballsandrea54Încă nu există evaluări

- The Greek Age of BronzeDocument23 paginiThe Greek Age of BronzeZorana DimkovićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neolithic Wetland and Lakeside Settlemen PDFDocument25 paginiNeolithic Wetland and Lakeside Settlemen PDFMartin Rizov100% (1)

- Bacchylides, Ed. KENYON 1897Document312 paginiBacchylides, Ed. KENYON 1897Caos22100% (1)

- Accusative and Dative Clitics in Southern Macedonian and Northern Greek Dialects - Eleni BužarovskaDocument17 paginiAccusative and Dative Clitics in Southern Macedonian and Northern Greek Dialects - Eleni BužarovskaSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- A Royal Macedonian Portrait Head From The Sea Off Kalymnos - Olga PalagiaDocument6 paginiA Royal Macedonian Portrait Head From The Sea Off Kalymnos - Olga PalagiaSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Македонските културни дејци: протонационални појави во XIX век - Александар СаздовскиDocument15 paginiМакедонските културни дејци: протонационални појави во XIX век - Александар СаздовскиSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- The Sindos Priestess - Despoina IgnatiadouDocument25 paginiThe Sindos Priestess - Despoina IgnatiadouSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- The Visual Communication System of The Early Byzantine Castles Along The Via Axia in The Republic of Macedonia in 6th Century AD - Viktor Lilchikj AdamsDocument29 paginiThe Visual Communication System of The Early Byzantine Castles Along The Via Axia in The Republic of Macedonia in 6th Century AD - Viktor Lilchikj AdamsSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Македонија во делата на арапските и персиските географи од средовековниот период - Зеќир РамчиловиќDocument17 paginiМакедонија во делата на арапските и персиските географи од средовековниот период - Зеќир РамчиловиќSonjce MarcevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Among Wetlands and Lakes: The Network of Neolithic Communities in Pelagonia and Lake Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia - Goce NaumovDocument14 paginiAmong Wetlands and Lakes: The Network of Neolithic Communities in Pelagonia and Lake Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia - Goce NaumovSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- A Lead Sling Bullet of The Macedonian King Philip V (221 - 179 BC) - Metodi ManovDocument11 paginiA Lead Sling Bullet of The Macedonian King Philip V (221 - 179 BC) - Metodi ManovSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Comfortably Sunk: Philip, The Battle of Chios and The List of Losses in Polybius - Stefan Panovski, Vojislav SarakinskiDocument11 paginiComfortably Sunk: Philip, The Battle of Chios and The List of Losses in Polybius - Stefan Panovski, Vojislav SarakinskiSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- Alexander's Cavalry Charge at Chaeronea, 338 BCE - Matthew A. Sears, Carolyn WillekesDocument19 paginiAlexander's Cavalry Charge at Chaeronea, 338 BCE - Matthew A. Sears, Carolyn WillekesSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- Inter-Regional Contacts During The First Millenium B.C. in EuropeDocument17 paginiInter-Regional Contacts During The First Millenium B.C. in EuropeSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Early Christian Reliquaries in The Republic of Macedonia - Snežana FilipovaDocument15 paginiEarly Christian Reliquaries in The Republic of Macedonia - Snežana FilipovaSonjce Marceva50% (2)

- Europe's Most Beautiful Coins From Antiquity To The Renaissance - Jürg ConzettDocument22 paginiEurope's Most Beautiful Coins From Antiquity To The Renaissance - Jürg ConzettSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Macedonian PeriodDocument1 paginăMacedonian PeriodSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Historical Change and Ceramic Tradition: The Case of Macedonia - Zoi KotitsaDocument15 paginiHistorical Change and Ceramic Tradition: The Case of Macedonia - Zoi KotitsaSonjce Marceva100% (2)

- Macedonia: Its Glorious Military History (1903)Document4 paginiMacedonia: Its Glorious Military History (1903)Sonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Gold Staters Coin Hoard From Skopje Region - Eftimija PavlovskaDocument9 paginiGold Staters Coin Hoard From Skopje Region - Eftimija PavlovskaSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- The Statue of Venus Pudica From Scupi - Marina Ončevska TodorovskaDocument12 paginiThe Statue of Venus Pudica From Scupi - Marina Ončevska TodorovskaSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- The Ancient Kingdom of Macedonia and The Republic of Macedonia - Viktor Lilchikj Adams, Igor Shirtovski, Vladimir Atanasov, Viktor Simonovski, Filip AdzievskiDocument84 paginiThe Ancient Kingdom of Macedonia and The Republic of Macedonia - Viktor Lilchikj Adams, Igor Shirtovski, Vladimir Atanasov, Viktor Simonovski, Filip AdzievskiSonjce Marceva100% (3)

- Pydna, 168 BC: The Final Battle of The Third Macedonian War - Paul LeachDocument8 paginiPydna, 168 BC: The Final Battle of The Third Macedonian War - Paul LeachSonjce Marceva100% (4)

- Greece 8 Northeastern Aegean Islands v1 m56577569830517605Document30 paginiGreece 8 Northeastern Aegean Islands v1 m56577569830517605Camila GregoskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asistenta Sociala 2nd SEMESTER SEMINAR 3, INTERMEDIATE LEVELDocument10 paginiAsistenta Sociala 2nd SEMESTER SEMINAR 3, INTERMEDIATE LEVELSimona NichiforÎncă nu există evaluări

- 04 Thasos English SDocument18 pagini04 Thasos English SPetar SkrobonjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Herrmann Thasian Statuettes Asmosia X PDFDocument8 paginiHerrmann Thasian Statuettes Asmosia X PDFJohn HerrmannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coin Collections and Coin Hoards From BuDocument104 paginiCoin Collections and Coin Hoards From BuSteven FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- THASOSDocument10 paginiTHASOSbilahod113Încă nu există evaluări

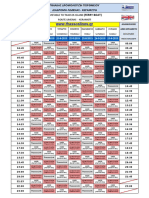

- Route Limenas - Keramoti Timetable To Thassos IslandDocument3 paginiRoute Limenas - Keramoti Timetable To Thassos IslandConstantin-Sebastian DămianÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18b - TO ΜΥΣΤΙΚΟ ΤΟΥ ΠΑΡΤΗΕΝΟΝΑ - EGDocument165 pagini18b - TO ΜΥΣΤΙΚΟ ΤΟΥ ΠΑΡΤΗΕΝΟΝΑ - EGO TΣΑΡΟΣ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΤΙΒΑΡΥΤΗΤΑΣ ΛΙΑΠΗΣ ΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣÎncă nu există evaluări

- Limenaria, A Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos - Stratis Papadopoulos, Dimitra MalamidouDocument20 paginiLimenaria, A Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlement at Thasos - Stratis Papadopoulos, Dimitra MalamidouSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- 7 Things To Do in KavalaDocument5 pagini7 Things To Do in Kavalaangeliki1992Încă nu există evaluări

- DOXIADIS - Sobre Els Assentaments de L'antiga Grècia (Selecció)Document42 paginiDOXIADIS - Sobre Els Assentaments de L'antiga Grècia (Selecció)Joaquim Oliveras MolasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hood - Minoan Long-Distance PDFDocument18 paginiHood - Minoan Long-Distance PDFEnzo PitonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thassos Marble DescriptionDocument31 paginiThassos Marble DescriptionerretemrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greece 8 Northeastern Aegean Islands - v1 - m56577569830517605 PDFDocument30 paginiGreece 8 Northeastern Aegean Islands - v1 - m56577569830517605 PDFOfelia RissoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12B - Greece The Most Rich Country, and Why - EgDocument21 pagini12B - Greece The Most Rich Country, and Why - EgO TΣΑΡΟΣ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΤΙΒΑΡΥΤΗΤΑΣ ΛΙΑΠΗΣ ΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greece-Thassos: Ioulia MousteiDocument4 paginiGreece-Thassos: Ioulia MousteisljindzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ThasosDocument12 paginiThasoskakashi 2501Încă nu există evaluări

- Campingreece enDocument88 paginiCampingreece enannaÎncă nu există evaluări