Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Towards A Semantics of X-Bar Theory: Jerry T. Ball

Încărcat de

Vernandes DegrityDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Towards A Semantics of X-Bar Theory: Jerry T. Ball

Încărcat de

Vernandes DegrityDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Towards a Semantics of X-Bar Theory

Jerry T. Ball

www.DoubleRTheory.com

Jerry@DoubleRTheory.com

Abstract

Grammar encodes meaning. X-Bar Theory captures an

important grammatical generalization. What is missing is a

semantics of X-Bar Theory. This paper is a step towards

providing such a semantics. In the process of providing a

semantics for X-Bar Theory, certain modifications to X-Bar

Theory are proposed to bring it into closer alignment with that

semantics. Referential and relational meaning are two key

dimensions of meaning that get grammatically encoded. It is

argued here that the relationship between a specifier and a

head is essentially referential in naturewith the specifier

determining the referential status of the overall expression. It

is likewise argued that the relationship between a head and its

complement(s) is essentially relational, and that only

relational heads (e.g. verbs, prepositions, adjectives, but not

nouns) take complements.

Grammar Encodes Meaning

I take it as axiomatic that grammar encodes meaning. This

position is consistent with Langackers claim (1987, p. 12)

that Grammar is simply the structuring and symbolization

of semantic content. I also take seriously Jackendoffs

Grammatical Constraint (1983, pp. 13-14) one should

prefer a semantic theory that explains otherwise arbitrary

generalizations about the syntax and the lexicona theorys

deviations from efficient encoding must be vigorously

justified, for what appears to be an irregular relationship

between syntax and semantics may turn out merely to be a

bad theory of one or the other.

X-Bar Theory is an important element of a larger theory

of Universal Grammar. The basic claim is that humans are

born with linguistic knowledge like that captured in X-Bar

Theory. Heretofore, X-Bar Theory has been investigated in

largely structural terms with little consideration of its

underlying semantic basis. This paper is an attempt to

provide a semantic basis for X-Bar Theory and to bring

syntactic theory into closer alignment with semantic theory.

Two key dimensions of meaning that get grammatically

encoded are referential meaning and relational meaning.

As will be shown, X-Bar Theory, with some modification,

can be explicated in terms of the encoding of these two

dimensions of meaning. In particular, it is argued here that

the relationship between a specifier and a head is essentially

referential in naturewith the specifier determining the

referential status of the overall expression. It is likewise

argued that the relationship between a head and its

complement(s) is essentially relational, and that only

relational heads (e.g. verbs, prepositions, adjectives, but not

nouns) take complements.

Referential Meaning

Within X-Bar Theory, specifiers are often defined

configurationally with a description like daughter of the

maximal projection (XP) which is sister to a non-minimal

head (X'

). The configurational definition of specifiers is

widely accepted and specifiers are typically considered to be

purely syntactic, making little or no contribution to

meaning. I have even heard a transformational grammarian

argue that the purely syntactic nature of specifiers provides

evidence for the independent reality of syntax.

On the other hand, there is some recognition of the

referential function of specifiers. For example, Speas (1990,

p. 37) notes that in one use the term specifier refers to

closed-class elements such as degree words and

determiners, which in some intuitive sense specify the

reference of the phrase but goes on to say that this

semantic sense of the term specifier is irrelevant. (Note

that degree words are treated here as modifiers, not

specifiers.) Stowell (1989) suggests that the special relation

between D [determiner] and N [noun] might be a function of

the status of CNPs [Common Noun Phrase] as referential

expressions. Chomsky (1995, p. 240) suggests that D may

be the locus of what is loosely called referentiality. On

the other hand, Stowell and Chomsky now treat D as the

head of DP and not a specifier, following the Functional

Head Hypothesis. However, others (e.g. Ernst, 1991;

Jackendoff, 2002) continue to argue for the treatment of D

as a specifier. Earlier, Chomsky (1970, p. 210) suggested

the treatment of determiners and auxiliary verbs as

specifiers, a position consistent with this paper. Di Sciullo

& Williams (1987, p. 50) suggest that perhaps in general

reference is associated only with maximal projections: NPs

refer to objects, Infl'refers to time, Comp'refers to truth

values. This is essentially the position adopted here except

that Infl0 (a specifier) supports reference to situations (not

time) and Comp0 (a specifier) supports reference to

objectified situations (not truth values). That is, reference is

associated with maximal projections, and specifiers

combine with heads to form maximal projections. The fact

that specifiers combine with heads to form maximal

projections is a reflection of their referential function

The two basic types of referring expressions are object

referring expressions which are grammatically encoded as

definite and indefinite noun phrases and situation referring

expressions which are grammatically encoded as finite and

non-finite clauses. As evidence that it is the specifier that

determines the grammatical (and referential type) of an

expression consider

The dance; to dance

The drink; to drink

The kill; to kill

The splash; to splash

The farm; to farm

The cat; to cat (about)

The dog; to dog (someone)

The father; to father

Since the head has the same word form (e.g. dance,

drink) in each contrasting expression, there is no basis for

the head determining the grammatical type of the

expression. Rather, it is the specifiereither the determiner

the or the infinitive marker tothat determines the

grammatical type of the expression. Thus, the specifier

the picks out an objective (or noun) sense of dance and

drink in forming a noun phrase, whereas the specifier to

picks out an action (or verb) sense of these words in

forming an infinitive phrase (or clause). Further, even in the

case of words which have a strong action preference, the

specifier the forces an object (or noun) reading as in the

case of the kill or the splash. That is, the has the

effect of objectifying the following head, often forcing

action words to be interpreted as one of the typical

participants in the action, rather than the action itself.

Likewise to has the effect of relationalizing the following

head. Thus, the words cat and dogwords which are

almost always used in expressions that refer to particular

kinds of objectsare relationalized by to and the base

meanings of cat and dog as categories of objects are

extended to support reference to relational attributes of

those objects and not the objects themselves.

The ability of a word which is typically used as a verb to

occur after a determiner, and a word which is typically used

as a noun to occur after the infinitive marker to is highly,

if not fully, productive. In both cases, the specifier

determines the grammatical type of the expression. Where a

contrasting noun or verb form exists, it is less acceptable as

in

The argument; *to argument

*The argue; to argue

The contrasting form blocks the productive use of the noun

as a verb or the verb as a noun. One can, of course,

construct examples that seem to be acceptable, if odd, as in

I dont like to argument with you. It is part of the creative

use of language to use words outside their typical

grammatical context. Clarks (1983) nonce expression he

porched the newspaper which I take to mean he threw the

newspaper on the porch is a classic example. Or the

language learner may lack the appropriate verb form and

resort to the verbal use of a noun form as in the to

argument example above. It also appears to be the case

that verbs expressing an instantaneous action are more

easily objectified and used after a determiner (e.g. the

kick, the hit, the bite) than other verbs. Verbs like

argue which do not express instantaneous actions are less

acceptable following a determiner.

The suggestion that the head determines the grammatical

type of an expression can only be maintained through a

circular argument that the head is necessarily of the same

type as the embedding expression whenever a difference in

type is apparent. Consider

The running of the bulls

The injured were taken to hospital

The sad are in need of cheering up

The cheering up of the sad

The buy out of the corporation

The porching of the newspaper

The status of the head as the determinant of a noun phrase

can only be maintained if we insist that the heads in these

examples are nouns. That is, since we know that these

expressions are noun phrases (because of the determiner),

their heads are necessarily nouns and these nouns determine

the type of the expressions. This circular argument has the

unfortunate side effect of allowing most any word or

expression to be a noun and clouds consideration of the

important notion part of speech.

If specifiers and not heads determine grammatical type,

then how can they be optional in many expressions? Some

words are inherently specified and function to combine the

head and specifier rolesobviating the need for a separate

specifier. This is true of pronouns, proper nouns, and

deictic words. Note that these words are inherently

referential and it is this fact that makes the need for a

separate specifier unnecessary. Also, the larger context may

redundantly encode the referential type of an expression

making the need for a specifier optional.

Thus, the

complementizer that (a specifier) in I believe (that) he

likes you is optional since the verb believe

subcategorizes for a clausal complement. The relative

pronoun (another specifier) is also optional in some forms

of relative clause. For example, the relative pronoun

which in the book (which) I gave you is optional. In

this case, the occurrence of the clause I gave you

following the subject the book establishes the clause as a

relative clause and allows the specifier to be optional.

On the other hand, the optionality of specifiers is much

less rampant than is assumed under some analyses. In

particular, the suggestion that all non-head sisters must be

maximal projections (with optional specifiers) is incoherent

from a referential perspective. For example, under this

assumption, red in the red book, is assumed to have the

status of an AP (adjective phrase) with the optional specifier

not appearing since it is a non-head sister of the head

book. But if red is not the maximal projection of an

AP, being instead just a modifier of the head book, then

there is no optional specifier. In fact, it is not clear what the

optional specifier could be in this example. Sadler &

Arnold (1994) argue that prenominal adjectives and adverbs

that modify them (e.g. very in the very red book) are

both bar zero. On their analysis, since they are not maximal

projections, there is no missing specifier. In general, the

assumption that all non-head sisters are maximal projections

combined with the binary branching hypothesis results in a

proliferation of phrase types where the specifier is at best

optional, if even possible. In this regard, the suggestion that

degree adverbs are specifiers in APs within NPs can be seen

as an attempt to find something that can be an optional

specifier where no specifier is possible (or needed).

If heads do not determine phrase or clause type, what do

they do? They determine the semantic category of object or

situation to which the phrase or clause may be used to refer.

For example, in the murder, murder determines the

semantic category that the murder may be used to refer to,

whereas, the determines the phrase to be a definite object

referring expressiondespite the fact that murder is an

action category. Likewise in he is sad, sad determines

the semantic type of situation that the expression may refer

to, whereas is determines the expression to be a finite

situation referring expression.

Thus, the specifier

determines the referential type of an expression, whereas,

the head determines the semantic type to which the

expression may be used to refer. It is referential type (e.g.

definite object referring expression or finite situation

referring expression) which corresponds most closely to the

grammatical notion of phrase and clause. That is, it is the

specifier and not the head which projects the grammatical

type of the expression.

Recognizing the important role of specifiers leads

immediately to a revision of X-Bar Theory that resolves

some important issues. The confusion over whether Tense

or V is the head of a TP (i.e. tensed phrase) results from the

assumption that the head projects the category of TP. But if

this is true, then Tense must be the head of TP as is assumed

by Chomsky (1995). On the other hand, V is the central

semantic category determining element of TP, with Tense

filling a more peripheral semantic role. That is, V has a

semantic prominence that does not hold for Tense. This

leads Jackendoff (1977, 2002) to assume that V (projected

thru VP) is the head of TP and not Tense. Recognizing that

the role of a specifier and the role of a head are distinct, it is

easy to see that Tense projects the type of TP, although V is

the central semantic element. Similarly, for COMP. If

COMP projects the type of CP, then COMP must be the

head according to Chomsky (1995). But COMP is clearly a

peripheral (and optional) element of CP with V (projected

thru TP) being the central element. This conflict is resolved

by making COMP the specifier which fulfills a peripheral,

but type determining role, while making V (projected thru

TP) the head or central semantic element of CP.

Cann (1999) comes close to the position put forward in

this paper in arguing that specifiers are secondary heads

whose features combine with the features of the head in the

formation of a maximal projection. Cann argues against

Chomskys (1995, p. 244) claim that only the features of the

head project. There is clearly something unsatisfying in

Chomskys (ibid. p. 246) claim that the word the in the

expression the book is the head whose syntactic features

projectespecially in a bare representation where the

categories NP and DP have been dispensed with. Yet,

Chomsky recognizes that the determiner the projects the

grammatical type of the overall expression and in an X-Bar

Theory where the head necessarily projects the grammatical

type, the determiner must be the head. Allowing both the

specifier and the head to project features avoids this

awkward position. Whether or not the specifier should be

considered a secondary head hinges on the issue of what

exactly the category of the parent is. I have argued above

that the specifier is the determinant of the grammatical type

of an expression and the head is the determinant of the

semantic type of that expression. From a grammatical

perspective, the specifier is the determining element and not

the head. That is, the grammatical influence of the specifier

overrides the semantic type of the head in determining the

grammatical function of the overall expression.

Relational Meaning

I argued above that the relationship between a specifier and

its head is essentially referential in nature. In this section, I

contend that the relationship between a head and its

complements is essentially relational in nature.

That the clause has a basic relational structure (on some

level) is widely accepted. However, syntactically, relational

structure is often subordinated to other considerations.

Thus, structurally we have VPs and PPs which are

relationally incomplete with the subject argument (in the

case of a VP) and the modified argument (in the case of a

PP) being treated as external to the construction. The

overall effect is the appearance that syntactic form and

relational form are distinct levels of representation.

In the case of PPs which typically function as modifiers

of Ns, NPs and clauses, relational structure is subordinated

to referential structure. For example, in the expression

The book on the table

the fact that the preposition on is a relation that takes two

arguments the book and the table is subordinated to the

referentially modifying relationship that exists between on

the table and the book. That is, the expression as a

whole is used to refer to a book which is on a table.

Nonetheless, if we view on the table as a relational

modifier (rather than a complement) of the book, then the

relational structure is still there, albeit subordinated. The

traditional syntactic treatment of expressions like

The book is on the table

is to make is the head with on the table functioning as a

complement, subordinating the relational meaning of on.

An alternative treats on as a relational head taking the

complements the book and the table with is providing

the specification needed to establish situational reference.

This alternative captures the idea that the expression is

about being on and not just being. The traditional

treatment is suggested by correspondence with Where is

the book? where the reference of on the table to a

location is emphasized. The alternative treatment is

suggested by correspondence with What is the book on?

where the relational content of is on is emphasized.

In the case of VPs, the situation is more complex. The

treatment of the subject as external to VP may have more to

do with trade-offs in the encoding of pragmatic meaning

than referential meaning. Thus, it is generally recognized

that the subject is an argument of the head of the VP on

some level, even if that relational reality is subordinated to

other concerns. In a grammatical theory limited to a single

level of representation like that being put forward here and

in Chomskys minimalist program, some mechanism for

simultaneously representing all dimensions of meaning is

needed. Trade-offs in the encoding of multiple dimensions

of meaning in a single linear dimension result in the

diversity of grammatical forms that is evident in language.

There may be expressions where relational meaning is

fully subordinated as in

where the relationship between the book and on the

table is fully subordinated to the requirement for the

complement on the table of put to be a referring

expression. In this case, the relational meaning of on is

only reconstructed via inference from the actual input.

In X-Bar Theory, the basic parts of speech are often

defined in terms of the features [N] and [V] as follows:

[+N] [- V]

[+N] [+V]

[- N] [+V]

[- N] [- V]

[???] [???]

The book of love

The preposition is ignored despite the fact that the

expression is ungrammatical without it:

*The book love

On the other hand, it is generally recognized that noun

complements are almost always optional. This is true

even in the case of deverbal nouns where the complements

of the deverbal noun occur in prepositional phrases and not

bare noun phrases as in the verbal use

The kick of the football by the kicker

He put the book on the table

Noun

Adjective

Verb

Preposition

Adverb

categorization based on the sem feature for the primary (i.e.

non-functional) parts of speech is provided above.

Note that nouns are [sem,obj] (object), whereas, all the

other primary parts of speech are [sem,rel] (relation). That

is, only nouns are non-relational. If nouns are nonrelational, then there is no semantic basis for suggesting that

they take complements, although most, if not all, X-Bar

Theory based approaches take it for granted that nouns do

take complements. From a relational perspective, X-Bar

Theory is seen as an overgenereralization in that is allows

all types of heads, including non-relational nouns, to take

complements. In treatments of noun complementation, the

preposition that almost always occurs as part of the

complement is typically ignored since it is often just a

semantically washed out preposition (e.g. of, at) as in

[sem,obj]

[sem,rel]

[sem,rel]

[sem,rel]

[sem,rel]

Given just two features, only four distinct, non-functional

parts of speech are identifiable. This is a clear limitation of

this element of X-Bar Theory since it provides no basis for

defining adverbs which by most accounts are a separate

non-functional part of speech. Further, while these features

are clearly motivated for the noun and verb categories, there

is less motivation for defining the adjective category as

[+N][+V], and hardly any motivation for defining the

preposition category as [-N][-V].

From a relational perspective, the key feature of each part

of speech is its relational status and the semantic featurevalue pair [sem,value] is suggested to represent this. A

Despite this grammatical evidence, prepositional phrases

following nouns are frequently treated as complements.

The alternative is to treat them as modifiers, not

complements. This is the position adopted here. From a

relational perspective, modifiers are non-head, relational

expressions. Thus, the prepositional phrases of the

football and by the kicker are relational expressions that

modify rather than complement the head.

Relational heads require specification to establish their

referential status. For verbs, the specifying function may be

marked by the tense on the verb as in

He kicked the ball.

For verb participles, adjectives and prepositions a separate

specifier is required as in

The man is running

The man is sad

The book is on the table

Relations used as modifiers do not require separate

specification since they are part of a referring expression

which has its own specification

The running man

The sad man

The book on the table

Adverbs are relations that modify relations and do not

typically function as heads and do not need specification:

The very sad man

He ran quickly

Degree adverbs are modifiers, not specifiers.

X-Bar Theory (Revisited)

Based on the semantic analysis presented in this paper a

revised version of X-Bar Theory is presented. Note that

although the default order of constituents for English is

reflected in these rules, the linear precedence is abstracted

out as in GPSG (Gazdar et al. 1985) and other orders are

possible. Also, like GPSG, features sets (other than [N]

and [V]) are introduced and individual features need not

take on binary values. Further, given that referential

meaning as reflected in the specifier/head relationship and

relational meaning as reflected in the head/complement

relationship are largely orthogonal, only two levels are

posited instead of the more common three levels. Further,

there is no assumption that the combining of a head with its

complements is internal to the combining of a specifier with

its head. Actually, the converse is claimed in the appendix.

Specifier/Head Rules

1. H1[ref,R][sem,S] => Spec[ref,R], Hn[sem,S]

2. H1[ref,R][sem,S] => H0[sem,S], Af[ref,R]

3. H1[ref,R][sem,S] => H0[ref,R][sem,S]

Head/Complement Rule

4. Hn[sem,sit] =>

Comp1[comp,subj], Hn[sem,rel], Comp2,3,4[comp,C]

Head/Modifier Rule

5. Hn => Mod, Hn

Terminology

[ref,R] = referential feature

R = {def,indef,fin,inf}

def = definite

indef = indefinite

fin = finite

inf = infinite

[sem,S] = semantic category feature

S = {obj,rel,sit}

obj = object

rel = relation

sit = situation

[comp,C] = complement feature

C = {subj,do,io,comp}

subj = subject

do = direct object

io = indirect object

comp = complement

Hn = H0 or H1 (H = head)

H1 implies [ref,R][sem,S]

H0 implies [sem,S]

Spec implies [ref,R] (Spec = specifier)

Mod implies [sem,rel] (Mod = modifier)

Comp implies [ref,R][sem,S]

Af = affix

The first three rules represent the specifier/head

relationship. Rule 1 is the case of an explicit specifier. Rule

2 handles affixes that provide specification (e.g. plural

marker on noun, tense marker on verb). Rule 3 handles

inherently specified lexical items (e.g. pronoun, proper

noun). In all three rules, the key to a maximal projection

(H1) is availability of the [ref,R] feature on one of the

constituents that forms the maximal projection. Without this

feature there is no maximal projection. Also note that the

head on the right hand side of the rule 1 is Hn to allow for

multiple specification as in all the men, the books,

has kicked.

Rule 4 represents the head/complement relationship. 0, 1

or 2 complements (Comp2,3,4[comp,C]) are allowed in

addition to the subject complement (Comp1[comp,subj]).

Note that the complements are maximal projections capable

of referring. Only relational heads (i.e. [sem,rel]) may take

complements. The relational head may be either H0 or H1.

Note that the head on the left hand side of the rule is

[sem,sit]. The combination of a relational head with its

complements results in a situation. The head/complement

rule allows for multiple complements and does not comply

with the binary branching hypothesis. It treats the subject as

a complement unlike most versions of X-Bar Theory that

assume subjects are specifiers, but closer to versions that

treat the subject as base generated internal to VP and raised

to TP specifier. Since the subject says nothing about the

referential status of the clause in which it occurs, it is a poor

candidate for being a specifier. On the other hand, since the

subject is an argument of the relational head of a clause it is

a good candidate for being a complement.

Rule 5 represents the head/modifier relationship.

Modifiers may combine with either H0 or H1 level

constituents with the resulting constituent having the same

bar level. The semantic features that a modifier contributes

to the head are not explored in this paper.

Summary

Providing a semantic basis for X-Bar Theory is a highly

laudable objective. If follows naturally from acceptance of

Jackendoffs Grammatical Constraint. This paper is a step

in that direction. Much detailed analysis is needed to flesh

out the consequences of providing a semantic basis for XBar Theory. See the appendix for some initial suggestions.

No doubt additional modifications will be needed. This

paper provides an outline of what such a semantics is likely

to look like.

Chomsky (1995, p. 246) eschews his own X-Bar Theory

in the minimalist program where he states that standard Xbar theory is thus largely eliminated in favor of bare

essentials. However, if X-Bar Theory can be given a

coherent semantic basis, then it may well turn out to be the

basis of LF (logical form), the single level of syntactic

representation that remains in the minimalist program.

Appendix

The rules above are very general and only weakly

constrained. Additional featural constraints can be posited

in more specialized variants of these rules.

1a. H1[ref,Ra][sem,obj] => Spec[ref,Ra], Hn[sem,obj]

where Ra = {def,indef}

1b. H1[ref,Rb][sem,rel] => Spec[ref,Rb], Hn[sem,rel]

where Rb = {fin,inf}

1c. H1[ref,Ra][sem,obj][sem,rel] =>

Spec[ref,Ra][sem,obj],H0[sem,rel]

1

1d. H [ref,Ra][sem,rel][sem,obj] =>

Spec[ref,Rb][sem,rel],H0[sem,obj]

1

1e. H [ref,def][sem,obj][sem,sit] =>

Spec[sub,comp][ref,def][sem,obj],H1[ref,fin][sem,sit]

where [sub,comp] is a complementizer subtype feature

Rules 1a and 1b are specialized specifier/head rules that are

constrained for referential and semantic type such that

def/indef reference type and obj semantic type co-occur and

fin/inf reference type and rel semantic type co-occur. Rule

1c specifically licenses deverbal nouns and rule 1d

specifically licenses the relational use of nouns. Note that

multiple semantic features are allowed on the head and are

not mutually exclusive. Spec[ref,Ra][sem,obj] is an object

specifier and Spec[ref,Rb][sem,rel] is a relation specifier.

H1[ref,Ra][sem,obj] corresponds to NP (i.e. object referring

expression) and H1[ref,Rb][sem,rel] corresponds to VG

(verb group) (i.e. relation referring expression). Rule 1e

specializes the

function

of a complementizer.

H1[ref,def][sem,obj][sem,sit] corresponds to an objectified

situation referring expression. Note the [ref,def] feature on

the specifier and the [ref,fin] feature on the relational head.

4a. H1[ref,fin][sem,sit] = finite clause =>

Comp1[comp,subj],H1[ref,fin][sem,rel],

4b. H1[ref,inf][sem,sit] = non-finite clause =>

ti[comp,subj],H1[ref,inf][sem,rel],

where ti[comp,subj] = subject trace

Rules 4a and 4b are specializations of the head/complement

rule. The fact that a finite clause [ref,fin] requires a subject

whereas a non-finite clause [ref,inf] does not shows that the

specifier/head rules and the head/complement rule are not

entirely orthogonal. However, it is the presence of the

[ref,inf] feature which licenses the subject trace and this

suggests that the relationship between a specifier and head

is internal to the relationship between a head and its

complements and not the other way around.

5a. Hn[sem,obj] => Mod[- adv], Hn[sem,obj]

5b. Hn[sem,rel] => Mod[+adv], Hn[sem,rel]

5c. Hn[sem,sit] => Mod[+adv], Hn[sem,sit]

5d. H1[ref,Ra][sem,obj] => H1[ref,Ra][sem,obj],

Mod[sub,wh-rel][ref,Ra],H1[ref,Rb][sem,sit]

Rules 5a, b, c and d are specializations of the head/modifier

rule. The head/modifier relationship can be specialized by

the addition of an adverb feature ([adv]) to capture the

distinction between modification of relations and situations

(i.e. by adverbs) and modification of objects (i.e. by other

modifiers).

Additional featural constraints can be introduced to reflect

the difference between pre- and post-modification. The

head/complement rule could be expanded to reflect the basic

clause types put forward in Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech &

Svartvik (1972) (SVC, SVA, SV, SVO, SVOC, SVOA,

SVOO), although the expanded head/complement rules may

handle adverbials (A) and complements (C) somewhat

differently. Assuming the existence of rules at differing

levels of specialization, the most specialized rule that

matches the linguistic expression will have precedence over

more general rules.

References

Cann, R. (1999). Specifiers as Secondary Heads. In

Specifiers, Minimalist Approaches, edited by Adger, D.

Pintzuk, S, Plunkett, B & Tsoulas, G. Oxford University

Press, Oxford, UK.

Chomsky, N. (1970). Remarks on Nominalization. In R.

Jacobs & P. Rosembaum, eds., Readings in English

Transformational Grammar. Ginn, Waltham, MA.

Chomsky, N. (1995). The Minimalist Program. Ellis

Horwood, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Clark, H. (1983). Making sense of nonce sense. In The

Process of Language Understanding. Edited by G. Flores

dArcais & R. Jarvella. John Wiley, New York, NY.

Di Sciullo, A. & Williams, E. (1987). On the Definition of

Word. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Ernst, T. (1991). A Phrase Structure Theory of Tertiaries.

In Syntax and Semantics 25, ed. By S. Rothstein.

Academic Press, New York, NY.

Gazdar, G., Klein, E, Pullum, G. and Sag, I. (1985).

Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar.

Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Jackendoff, R. (2002) Foundations of Language. Oxford

University Press, New York, NY.

Jackendoff, R. (1983). Semantics and Cognition. The MIT

Press, Cambridge, MA.

Jackendoff, R. (1977). X-Bar Syntax. The MIT Press,

Cambridge, MA.

Langacker, R. (1987). Foundations of Cognitive Grammar,

Volume 1. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, & J. Svartvik (1972). A

Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman

Sadler, L. & Arnold, D. (1994). Prenominal adjectives and

the phrasal/lexical distinction. Journal of Linguistics, 30,

pp. 187-226.

Speas, M. (1990). Phrase Structure in Natural Language.

Kluwer, London, UK.

Stowell, T. (1989). Subjects, Specifiers, and X-Bar

Theory. In Alternative Conceptions of Phrase Structure,

ed. By M. Baltin & A. Kroch, The University of Chicago

Press, Chicago, IL.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms: American English Idiomatic Expressions & PhrasesDe la EverandThe American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms: American English Idiomatic Expressions & PhrasesEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Level H Answers - Vocabulary WorkshopDocument27 paginiLevel H Answers - Vocabulary Workshopandrewwroble18% (11)

- Cohesion in Discourse Analysis 1Document43 paginiCohesion in Discourse Analysis 1Irish BiatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noun PhraseDocument20 paginiNoun PhraseIuliana BiţicăÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diachronic SyntaxDocument523 paginiDiachronic SyntaxMeliana Mustofa100% (3)

- Coherence AND CohesionDocument49 paginiCoherence AND CohesionChloePauÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Year 7 SchemeDocument8 paginiEnglish Year 7 SchemeMaoga2013Încă nu există evaluări

- Cohesion and CoherenceDocument46 paginiCohesion and CoherenceDaphne PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cohesion and Coherence 1224552963587167 8Document77 paginiCohesion and Coherence 1224552963587167 8Najah Sofea100% (1)

- Extension, Intension, Character, and Beyond by D. Braun (2012)Document18 paginiExtension, Intension, Character, and Beyond by D. Braun (2012)Tony MugoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hockey 46546546Document6 paginiHockey 46546546pardeepbthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noun PhraseDocument20 paginiNoun PhraseUnalyn UngriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noun Phrase (I)Document7 paginiNoun Phrase (I)Alina RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clause Structure, Complements, and Adjuncts: February 2020Document29 paginiClause Structure, Complements, and Adjuncts: February 2020Ali Muhammad YousifÎncă nu există evaluări

- LEC - Noun Phrase, An I, Sem. 1 IDDocument40 paginiLEC - Noun Phrase, An I, Sem. 1 IDlucy_ana1308Încă nu există evaluări

- Coherence: A Very General Principle ofDocument75 paginiCoherence: A Very General Principle ofPrince Monest JoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grammatical Cohesion and TextualityDocument5 paginiGrammatical Cohesion and TextualityMaya MuthalibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparing Generative and Interpretive SemanticsDocument5 paginiComparing Generative and Interpretive SemanticsPutriRahimaSariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syntax: Language and StructureDocument5 paginiSyntax: Language and StructureSITI SALWANI BINTI SAAD MoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of The Right Hand Head Rule inDocument4 paginiThe Role of The Right Hand Head Rule inOkunola Demilade SamuelÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Sentence-MeaningDocument11 pagini4 Sentence-MeaningCamiRusuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Humanities Ed3 5Document18 paginiHumanities Ed3 5abdulhadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Language DeterminativeDocument3 paginiEnglish Language DeterminativeJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Words David KaplanDocument27 paginiWords David KaplanUmut ErdoganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 2-1966 On So-Called PronounsDocument14 paginiWeek 2-1966 On So-Called PronounspizzacutfiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thuren 06 The Syntax of SDocument25 paginiThuren 06 The Syntax of STheodora Cristina CanciuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Event Argument and The Semantics of Verbs. Chapter 1Document20 paginiThe Event Argument and The Semantics of Verbs. Chapter 1Wânia MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Textual CohesionDocument5 paginiTextual CohesionVilma AlegreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lexical Phonology & MorphologyDocument3 paginiLexical Phonology & MorphologyMaruf Alam MunnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- G & S - Term Paper - MA 3rdDocument10 paginiG & S - Term Paper - MA 3rdKamran MuzaffarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-Lesson 1 Syntax 2021Document5 pagini1-Lesson 1 Syntax 2021AYOUB ESSALHIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignmnent 2Document7 paginiAssignmnent 2Thirumurthi SubramaniamÎncă nu există evaluări

- NP From The NetDocument9 paginiNP From The NetAleksandra Sasha JovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noun of Address: Nouns (Or Non-Count Nouns), Which Name Something That Can't Be Counted (Water, AirDocument16 paginiNoun of Address: Nouns (Or Non-Count Nouns), Which Name Something That Can't Be Counted (Water, Airmsaadshuib757390Încă nu există evaluări

- English Determining FactorDocument3 paginiEnglish Determining FactorJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coursework LADocument10 paginiCoursework LANguyễn TrangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Living (Happily) With Contradiction: WorkingDocument8 paginiLiving (Happily) With Contradiction: WorkingmilkoviciusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Are That'-Clauses Singular Terms? 1Document21 paginiAre That'-Clauses Singular Terms? 1gensai kÎncă nu există evaluări

- English People CausalDocument3 paginiEnglish People CausalJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cataphoric ReferenceDocument3 paginiCataphoric ReferenceRany GarcíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Nearly SlipDocument3 paginiIn Nearly SlipJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Nearly ShowcaseDocument3 paginiIn Nearly ShowcaseJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Document6 pagini2mumin jamalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lý Thuyết ReferenceDocument31 paginiLý Thuyết Reference02 Nguyễn Ngọc Trâm AnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 5 - TBI 3 - Discourse GrammarDocument9 paginiGroup 5 - TBI 3 - Discourse GrammarSiti MutiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lexical Relations: Entailment Paraphrase ContradictionDocument8 paginiLexical Relations: Entailment Paraphrase ContradictionKhalid Minhas100% (1)

- English People DeterminantDocument3 paginiEnglish People DeterminantJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Paradox of Identity Easier To Read TDocument22 paginiThe Paradox of Identity Easier To Read TLucas VolletÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parts of SpeechDocument19 paginiParts of Speechzafar iqbalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phân Tích Diễn NgônDocument12 paginiPhân Tích Diễn Ngônphuogbe099Încă nu există evaluări

- The Structure of NPDocument20 paginiThe Structure of NPPhạm Quang ThiênÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gramatical Cohension and TextualityDocument6 paginiGramatical Cohension and TextualitywaodeazzahraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Side Determinative (Document3 paginiSide Determinative (Jax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cohesion and CoherenceDocument4 paginiCohesion and CoherenceMaryRuby BisnarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parts of SpeechDocument1 paginăParts of SpeechEljohn Charl CaraanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discourse StudyDocument44 paginiDiscourse StudylidianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Virtually CompositorDocument3 paginiIn Virtually CompositorJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clincher Appear inDocument3 paginiClincher Appear inJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Are Basic English Grammar RulesDocument2 paginiWhat Are Basic English Grammar Rulesalexandra jacob100% (1)

- In About FaceDocument3 paginiIn About FaceJax SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Referencial Semantics and The Meaning of Natural Kind Terms: Ralph Henk VaagsDocument35 paginiReferencial Semantics and The Meaning of Natural Kind Terms: Ralph Henk VaagsThiago DiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sugar, Though They Possess Different Grammatical Meanings of NumberDocument3 paginiSugar, Though They Possess Different Grammatical Meanings of NumberЄлизавета Євгеніївна КічігінаÎncă nu există evaluări

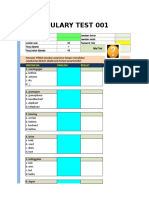

- Test Vocabulary 2000 Words, Part OneDocument190 paginiTest Vocabulary 2000 Words, Part OneVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bahasa Inggris Kelas VIIaDocument20 paginiBahasa Inggris Kelas VIIaVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statement of Originality: I Certify This Paper Which Is Submitted As An Assignment of English For YoungDocument1 paginăStatement of Originality: I Certify This Paper Which Is Submitted As An Assignment of English For YoungVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language and SexDocument15 paginiLanguage and SexVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper Translation FixDocument13 paginiPaper Translation FixVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- AFFECTIVE DOMAIN of SECOND LANGUAGE1Document14 paginiAFFECTIVE DOMAIN of SECOND LANGUAGE1Vernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Test For Second Grade of MTs. Smster 1 1617Document4 paginiEnglish Test For Second Grade of MTs. Smster 1 1617Vernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is A LexiconDocument1 paginăWhat Is A LexiconVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPU: Central Processing Unit VGA: Video Graphic Adapter LAN: Local Area Network WAN: Wide Area Network LCD: LikuidDocument1 paginăCPU: Central Processing Unit VGA: Video Graphic Adapter LAN: Local Area Network WAN: Wide Area Network LCD: LikuidVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affective Domain of Second Language1Document14 paginiAffective Domain of Second Language1Vernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asesmen PAI Di PT UmumDocument28 paginiAsesmen PAI Di PT UmumVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jerry Jinks©1997 Illinois State University 1997Document8 paginiJerry Jinks©1997 Illinois State University 1997Vernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lexicon: Citation NeededDocument6 paginiLexicon: Citation NeededVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper Communicative Language Teaching 2Document5 paginiPaper Communicative Language Teaching 2Vernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common DataDocument10 paginiCommon DataVernandes DegrityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amelia Jackson Eed 354 RubricDocument9 paginiAmelia Jackson Eed 354 Rubricapi-288535461Încă nu există evaluări

- Noun Clause: M.Khresna Dirgantara A1B019034 4BDocument11 paginiNoun Clause: M.Khresna Dirgantara A1B019034 4BTatsuya RinÎncă nu există evaluări

- L3 PropositionalEquivalencesDocument30 paginiL3 PropositionalEquivalencesAbhishek KasiarÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENG G10 Q4 Prepositions of Time and Place WK13 24march2020Document18 paginiENG G10 Q4 Prepositions of Time and Place WK13 24march2020Chelsea Leigh L. Tianio100% (1)

- Bowker Translation MemoriesDocument8 paginiBowker Translation MemoriesGabriela Valles MonroyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bvoc Maths: LogicDocument24 paginiBvoc Maths: LogicArt PlatformÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 11 - 13 - BRM - Kel - 3 (Update)Document88 paginiChapter 11 - 13 - BRM - Kel - 3 (Update)Grace Jane SinagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historical RealiasDocument7 paginiHistorical RealiasNadia PavlyukÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alice in Wonderland PDFDocument15 paginiAlice in Wonderland PDFVatsalya GoparajuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task Type and Linguistic Performance in School-Based Assessment SituationDocument10 paginiTask Type and Linguistic Performance in School-Based Assessment SituationAhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADJECTIVES-WPS OfficeDocument5 paginiADJECTIVES-WPS OfficeRizki 1708Încă nu există evaluări

- PROPOSAL FebyDocument26 paginiPROPOSAL Febyrahmathia tiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cómo Te LlamasDocument34 paginiCómo Te LlamasKatherine ChristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anthropological Approaches To The Philosophy of TranslationDocument320 paginiAnthropological Approaches To The Philosophy of TranslationRob Thuhu100% (1)

- Summary Morphology Chapter 4Document10 paginiSummary Morphology Chapter 4Maydinda Ayu PuspitasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Verb Patterns: Week 6 by Miss ImaDocument13 paginiVerb Patterns: Week 6 by Miss ImaIma FirdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Plan in Mapeh 8Document7 paginiLearning Plan in Mapeh 8Dion100% (1)

- 5.1 Logic and ProofsDocument21 pagini5.1 Logic and ProofsNecole Ira BautistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- WORD FORMATION in EbglishDocument9 paginiWORD FORMATION in EbglishMary Grace SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elt 208Document5 paginiElt 208Elle BeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjectives Tell What Kind Worksheet PDFDocument2 paginiAdjectives Tell What Kind Worksheet PDFRondelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pronoun: Aira Dita Ricki Prisma P Rindu Nurani Vasya Olivia Ezra FebrianDocument14 paginiPronoun: Aira Dita Ricki Prisma P Rindu Nurani Vasya Olivia Ezra FebrianVasya OliviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Code SwitchingDocument10 paginiCode SwitchingBagas TiranggaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2010 English Standards of Learning Grammar Skills Progression by GradeDocument1 pagină2010 English Standards of Learning Grammar Skills Progression by GradeDuyen NgocÎncă nu există evaluări

- AFC1-Functional English QuestionbankDocument158 paginiAFC1-Functional English QuestionbankAhsan Tirmizi100% (1)

- Subject Verb Agreement ModuleDocument8 paginiSubject Verb Agreement ModuleJUNAID MASCARAÎncă nu există evaluări