Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cambridge Baseline Study 2013

Încărcat de

Buenaventura Casimiro MarshallDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cambridge Baseline Study 2013

Încărcat de

Buenaventura Casimiro MarshallDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Introduction

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION

Project background and aims

Cambridge English expertise

Conceptual framework

Key questions

Structure of the report

2. METHODOLOGY

Research design: Convergent parallel mixed-method design

Project sample

Data collection instruments

13

Data analysis

13

Project timeline

14

Limitations

14

3. STUDENT ENGLISH LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY

Overall national profile

17

Summary: National profile

36

National profile: Comparison with other countries

38

State profiles

40

Urban/rural/remote profiles

46

School type profiles

55

Gender profiles

62

Class specialisation profiles

68

High performing versus low performing learners

71

Summary

76

4. TEACHER ENGLISH LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY, TEACHING KNOWLEDGE AND TEACHING PRACTICE

Language proficiency: Teachers

79

Teaching Knowledge

88

Teaching practice

93

The role of assessment in learning and teaching

106

5. CURRICULA, LEARNING MATERIALS AND NATIONAL EXAMINATIONS

Curricula

111

Learning materials

115

National exams

118

6. RECOMMENDATIONS AND NEXT STEPS

120

REFERENCES

124

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Introduction

1.

Project background and aims

Malaysia has embarked upon a visionary English language education reform programme which will fundamentally

transform the existing system, providing the young people of Malaysia with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and

beliefs to enable them to become global citizens of the 21st century.

In October 2011, the Ministry of Education launched a review of the education system in order to develop a new

National Education Blueprint the Malaysia Education Blueprint 20132025 (referred to as the Education

Blueprint in the rest of this document). This document recognises the increasing importance of English as a global

language and the fact that the English proficiency of the population of a country is linked to its economic

development:

Education is a major contributor to the development of our social and economic capital Prime

Minister of Malaysia: DatoSri Mohd Najib bin Tun Haji Abdul Razak, Education Blueprint

Therefore, in 2013 the Ministry commissioned Cambridge English Language Assessment to undertake a

comprehensive evaluation of the learning, teaching and assessment of English language in Malaysian schools from

Pre-school to pre-university.

The resulting evidence-based 2013 baseline gives the Ministry a clear picture of how the Malaysian English

language education system is currently performing against internationally recognised standards. The findings and

recommendations will act as the basis for discussion with the Ministry so that together Cambridge English

Language Assessment and the Ministry can move to the next phase of collaboration.

Cambridge English expertise

Cambridge English is uniquely positioned to deliver these services to the Ministry of Education given our expertise

in educational reform, especially where English is concerned. We deliver over 4 million language assessments

every year and have worked with governments and organisations around the world on similar projects.

The effective and timely delivery of the baseline project involved a unique team of Cambridge English staff and

external consultants with extensive expertise and experience in the fields of English language assessment,

curricula development, teacher training and development, primary and secondary education, sampling, research

methodology, data analysis, operational delivery and processing, and educational reform.

Conceptual framework

Central to the design of this project was the construct of communicative language competence, which has become

widely accepted as the goal of language education and as central to good classroom practice (Canale and Swain

1980; Bachman and Palmer 1982). Communicative language competence comprises linguistic competence, as well

as the ability to functionally use that competence in language activities which involve oral and/or written

reception, production and interaction in different domains. An approach driven by a communicative view entailed

the inclusion of the four language skills of Reading, Listening, Writing and Speaking in the investigation of the

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Introduction

student and teacher English language baseline. Measuring just the receptive skills of Reading and Listening, albeit

the most straightforward from a test administration perspective, would have given only a partial picture of the

level of English proficiency of students and teachers. It was felt important, therefore, to include Speaking and

Writing in the project as well, in order to gain a more comprehensive and accurate view of the language

proficiency baseline.

A further conceptual premise underlying the project was the belief in the importance in triangulating the

investigation of English language proficiency with a complementary investigation of lesson observations and

teacher subject and pedagogic knowledge. Such an approach allowed us to develop a more in-depth view of

Malaysia English teachers profiles and their impact on student English language proficiency.

Teachers and students do not exist in a vacuum, but are part of an ecological system which also includes

documents such as curricula, textbooks and examinations, which often determine policy, classroom practices and

educational impact. As such, one strand of the project included a review of current primary and secondary school

curricula, national textbooks and examinations.

Taking into consideration the views of stakeholders is a further important conceptual premise which was

fundamental to the project. The context of and stakeholder attitudes to English language learning and teaching

can provide insight into factors that may be influencing learning outcomes. Therefore, background and attitudinal

questionnaires for teachers, students and Heads of Panel/Head Teachers, as well as interviews with teachers,

Heads of Panel/Head Teachers and policy planners from the Ministry of Education, comprised a further strand in

the project.

The Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR, Council of Europe 2001) provides a useful common basis

for the investigation of many of the questions of interest in the project, such as language proficiency, curricula,

examinations and textbooks. The CEFR:

describes in a comprehensive way what language learners have to learn to do in order to use

language for communication and what knowledge and skills they have to develop so as to be

able to act effectively. The Framework also defines levels of proficiency which allow

learners progress to be measured at each stage of learning and on a life-long basis (Council

of Europe 2001:1).

The CEFR, therefore, provided a useful tool for description and comparison, which also allowed the findings of the

project to be considered against a broader international context where the CEFR is used. The CEFR describes a set

of six broad common reference levels, which cover the language learning continuum from a basic Breakthrough

level to an advanced Mastery level. The CEFR is not Europe-specific and has also been used beyond Europe,

either in its original form or adapted to different contexts, e.g. the CEFR-J is an adaptation of the original CEFR to

language teaching, learning and assessment in Japanese contexts (Negishi, Takada and Tono 2013).

The CEFR common reference levels and the Can Do statements which characterise the levels can be seen in Table

1.1. The Can Do statements for each level will be useful reference points for readers of this report, since they

specify in broad terms what the baselines established for the different cohorts in the project actually mean.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Introduction

Table 1.1 CEFR Common reference levels: Global scale (Council of Europe 2001:33)

C2

C1

Proficient

User

B2

Independent

User

B1

A2

Basic User

A1

Can understand with ease virtually everything heard or read.

Can summarise information from different spoken and written sources,

reconstructing arguments and accounts in a coherent presentation.

Can express him/herself spontaneously, very fluently and precisely,

differentiating finer shades of meaning even in the most complex situations.

Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer texts, and recognise

implicit meaning.

Can express ideas fluently and spontaneously without much obvious

searching for expressions.

Can use language flexibly and effectively for social, academic and

professional purposes.

Can produce clear, well-structured, detailed text on complex subjects,

showing controlled use of organisational patterns, connectors and cohesive

devices.

Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both concrete and

abstract topics, including technical discussions in his/her field of

specialisation.

Can interact with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that makes regular

interaction with native speakers quite possible without strain for either

party.

Can produce clear, detailed text on a wide range of subjects and explain a

viewpoint on a topical issue giving the advantages and disadvantages of

various options.

Can understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters

regularly encountered in work, school, leisure, etc.

Can deal with most situations likely to arise while travelling in an area where

the language is spoken.

Can produce simple connected text on topics that are familiar or of personal

interest.

Can describe experiences and events, dreams, hopes and ambitions and

briefly give reasons and explanations for opinions and plans.

Can understand sentences and frequently used expressions related to areas

of most immediate relevance (e.g. very basic personal and family

information, shopping, local geography, employment).

Can communicate in simple and routine tasks requiring a simple and direct

exchange of information on familiar and routine matters.

Can describe in simple terms aspects of his/her background, immediate

environment and matters in areas of immediate need.

Can understand and use familiar everyday expressions and very basic

phrases aimed at the satisfaction of needs of a concrete type.

Can introduce him/herself and others and can ask and answer questions

about personal details such as where he/she lives, people he/she knows and

things he/she has.

Can interact in a simple way provided the other person talks slowly and

clearly and is prepared to help.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Introduction

Key questions

The project was guided by the following set of key questions:

Students: Language proficiency

1. How do students at different school stages in the Malaysian states/federal territories perform on a set of

Cambridge English language tests overall and by skill (Reading, Writing, Listening, Speaking) against the

CEFR?

2. How does overall and by skill student performance at different school stages compare according to:

a. state/federal territory (16 states/federal territories)

b. location (urban/rural/remote)

c. type of school (National, Chinese, Tamil at Primary; National and Religious at Secondary)

d. gender (male/female)

e. class specialisation at Form 5 and 6 (Arts, Science, Religious, Vocational/Technology)?

Teachers: Language proficiency, teaching knowledge and teaching practice

Language proficiency

3. How do teachers teaching at different school stages in Malaysian states/federal territories perform on a

set of Cambridge English language tests overall and by skill (Reading, Writing, Listening, Speaking) against

the CEFR?

4. How does overall and by skill teacher performance compare according to:

a. school stage (primary/secondary)

b. location (urban/rural/remote)?

Teaching knowledge

5. How do teachers teaching at different school stages in the Malaysian states/federal territories perform

overall on a test of teaching knowledge?

6. How does teaching knowledge compare according to:

a. school stage (primary/secondary)

b. location (urban/rural/remote)?

Teaching practice

7. How do teachers teaching at different school stages in the Malaysian states/federal territories perform

overall in terms of teaching practice based on classroom practice evaluations and observations and postobservation discussions?

8. How does teaching practice compare according to:

a. school stage (primary/secondary)

b. location (urban/rural/remote)?

Curricula, national textbooks and examinations

9. What are the features of currently used learning, teaching and assessment materials (e.g. curricula,

textbooks, national tests) according to international standards, e.g. the CEFR, and according to current

trends in teaching practice?

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Introduction

Recommendations

10. What recommendations can be made, based on the benchmarking of teachers/students and the

evaluation of teaching/assessment materials, to enable the achievement of the envisioned education

transformation by the Malaysia Ministry of Education?

Structure of the report

The report is structured following the key aims and questions which underlie it. After the introduction (Section 1),

an overview of the methodology will be given (Section 2), outlining how the project was carried out in terms of

research design, data collection, analysis and participants. The findings on student English language proficiency

then follow (Section 3), with a focus on the overall and by-skill performance of the five school grades of interest

and the attitudinal and background factors which play a role in English language achievement. The performance of

the cohorts overall is followed by an investigation of performance based on key variables and comparisons

between them, such as: states/federal territories; urban, rural and remote location; school types; gender; class

specialisation. The next section (Section 4) presents findings on teacher English language proficiency, teaching

knowledge and teaching practice. In each case, performance overall is given, followed by comparisons based on

key variables, such as urban, rural and remote location, and primary/secondary school. The test performance

findings are integrated with findings about attitudinal and background variables which play a role in teacher

attainment, open-ended comments from the teacher questionnaire, interviews with Heads of Panel/Head

Teachers and Ministry of Education officials, and extended feedback from the classroom observers. The review of

key policy-setting documents which shape the learning, teaching and assessment in classrooms follows (Section 5),

with a discussion of current curricula, learning materials and examinations. Finally, the report ends with a set of

recommendations which emerge as a result of the qualitative and quantitative findings, and suggestions for ways

forward (Section 6).

More detailed information on the project, including sampling, project participants, instrument development, data

analysis procedures and significance testing output can be found in the Cambridge Baseline 2013 Technical Report.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

2.

The large-scale scope of the project and its aim, i.e. to build up a comprehensive profile of English language

education in Malaysia in order to provide the Ministry of Education with data-driven recommendations for

improving English language standards in Malaysia, necessitated a research design which allowed the gathering of

different types of information through the use of a range of tools. A premise recognised in educational reform is

that a key characteristic of the educational process is that student learning is influenced by many small factors

rather than a few large ones (Chapman, Weidman, Cohen and Mercer 2005:526); therefore, any

recommendations made in this project need to be based on an in-depth understanding of all aspects of the

educational system in order to ensure they are achievable and reduce the chances of any negative unintended

consequences. As a result, the project focused not only on measuring English language levels of students and

teachers, but also on investigating the context of learning, the availability and quality of resources, and

stakeholder perceptions. A mixed-method approach formed the basis of the study and a convergent parallel

design (Creswell 2009) was chosen due to its value in collecting qualitative and quantitative data strands in a

parallel fashion and in relatively short timeframes.

Research design: Convergent parallel mixed-method design

A fundamental feature of the convergent parallel mixed-method design is that it consists of two data strands a

qualitative and a quantitative one. These occur independently and concurrently, are analysed separately and

findings are then converged and integrated to inform the final overall findings. The key assumption of this design

is that a complex project, such as for example a national survey, can best be understood by gathering and

investigating different types of information which provide insights into different aspects of the project. A typical

aim, therefore, is to use large-scale statistical quantitative findings and detailed qualitative insights to develop an

in-depth understanding of a situation or an event through integrating these two types of information.

The use of two data collection strands in the Cambridge Malaysia Baseline Project one quantitative and one

qualitative allowed the project to maximise the value of two different research methodologies which are

grounded in different theoretical paradigms and interpret data through different lenses. The quantitative

paradigm underlies research which is based on large data sets, representative samples and statistical methods. A

quantitative strand was, therefore, well suited to the investigation of student/teacher language ability, teacher

pedagogic knowledge and stakeholder views through a suite of tests and questionnaires. The qualitative paradigm

draws on discovery and description; it is inductive and uses small purposefully chosen samples. It was, as such,

well suited to observations of classroom practices, interviews with stakeholders, comments written in response to

open-ended questions by stakeholders, and curricula, textbooks and examination reviews. This approach allowed

the project to build a rich picture of the current situation with regards to learning, teaching and assessment in

Malaysia and enhance the validity of the findings. Figure 2.1 presents an overview of the data collection and data

analysis procedures which formed the backbone of the project.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

Figure 2.1 Research design

QUANTITATIVE DATA COLLECTION

Benchmarking tests for students

and teachers

Questionnaires for students,

teachers and education leaders

Classroom observations teaching

practice assessment

QUANTITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics of test scores

and questionnaire responses (mean

and standard deviation; frequency

%, mode)

Mapping onto CEFR levels (Rasch

analysis and ability estimates)

Linear and logistic regression

Multilevel modelling

INTEGRATION

AND

INTERPRETATION

QUALITATIVE DATA COLLECTION

Comments in questionnaires for

students, teachers and leaders

Semi-structured interviews with

policy planners

Classroom observations observer

comments and post-observation

discussions

Review of curricula, examinations,

learning materials

QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

Thematic analysis of questionnaire

comments, interviews, classroom

observations notes and document

review trends

Project sample

The participants included students at five different age ranges, teachers, Heads of Panel/Head Teachers and policy

planners. Specific information on their distribution within the sample can be seen in Table 2.1. The selected

schools were chosen as part of a two-part stratified sampling methodology (i.e. schools were selected first based

on a range of variables and then students were selected within each school). This methodology resulted in a

sample which was intended to be representative of the overall target population.

10

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

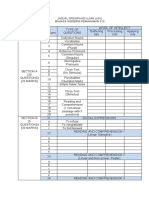

Table 2.1 Participants: by data collection instruments

Participants

Tests

Interviews

Qres

Reading/

Listening

Writing

Speaking

20402

9921

1372

Pre-school

3430

2127

187

12

Year 6

4795

1328

206

14

4956

Form 3

4858

2422

331

16

4740

Form 5

5458

2941

431

23

5495

Form 6

1861

1103

217

13

1913

424

266

42

600

78

1290

Primary

115

71

13

196

26

558

Secondary

287

188

29

352

52

732

Unknown

22

52

Students

Teachers

Teaching

knowledge

Classroom

observations

(Number of

classes)

17104

Heads of

Panel/Head

Teachers

41

31

Primary

14

Secondary

27

22

Ministry of

Education

Figure 2.2 shows the distribution of students by school grade. As can be seen, the sample covered all school

grades of interest, with Year 6, Forms 3 and 5 having a roughly similar proportion, and Form 6 having the smallest

proportion of students in the sample due to the smaller proportion of Form 6 in the target population.

Figure 2.2 Distribution of students by school grade (N=20,402)

Form 6

9%

Form 5

27%

Pre-school

17%

Year 6

23%

Form 3

24%

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

11

The distribution of teachers in the sample can be seen in Figure 2.3, which shows that approximately one quarter

of the teachers in the survey came from the primary school level, and approximately two thirds came from

secondary schools.

Figure 2.3 Distribution of teachers by primary/secondary school (N=424)

Unknown

5%

Primary

27%

Secondary

68%

In addition to the language tests for teachers and students, questionnaires for students, teachers and Head

Teachers/Heads of Panel were also distributed in order to allow the collection of attitudinal and background data.

The distribution of completed questionnaires across the different school grades is given in Figure 2.4. Pre-school

children were not included in the questionnaire data, due to concerns with the reliability and validity of

questionnaire data supplied by young children (Borgers, Leeuw and Hox 2000).

Figure 2.4 Distribution of student questionnaire responses by school grade (N=17,104)

Form 6

11%

Year 6

29%

Form 5

32%

Form 3

28%

12

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

The distribution of teacher questionnaire responses by primary/secondary school is shown in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 Distribution of teacher questionnaire responses by primary/secondary school (N=1,290)

Primary

43%

Secondary

57%

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

13

Data collection instruments

A range of instruments was used to allow the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data. They comprised:

Benchmarking English language tests for students and teachers: aimed at providing information on

language proficiency, in terms of Reading, Listening, Writing and Speaking as measured against the

CEFR

Benchmarking teaching knowledge test for teachers: intended to provide a measure of knowledge of

and familiarity with teaching knowledge concepts in an objectively-scored test

Student, teacher and Head of Panel/Head Teacher questionnaires: aimed to gather stakeholder

perceptions of and attitudes toward English language learning, teaching and assessment

Classroom observations and post-observation discussions: intended to gather in-depth information on

teaching competence and performance for a smaller sub-set of the selected sample

Semi-structured interviews with policy planners and senior school administrators: focused on

exploring perceptions of the review project and expected outcomes, as well as views on curriculum,

textbooks, examinations, teaching practice

Curricula, textbooks and examinations review: intended to investigate issues such as the relationship

between standards, curricula, textbooks and examinations and the CEFR; information on the extent to

which the different documents complement each other and reflect latest trends in learning, teaching

and assessment, e.g. student-centred learning and teaching, learning-oriented assessment,

communicative-ability assessment.

Data analysis

As noted above (Figure 2.1), the mixed-method research design underlying this project involved both qualitative

and quantitative analyses, which comprised:

CEFR level mapping: Rasch analysis and ability estimates

Descriptive statistics in the quantitative strand: aimed to provide an overall picture of CEFR language

level, teaching knowledge and stakeholder perceptions, as well as the amount of variability within each

group. The analysis focused on the cohort as a whole (e.g. all Form 5 students) and on specific variables

within the cohort (e.g. Form 5 boys and girls; Form 5 urban, rural and remote students)

Linear and logistic regression: aimed to investigate which background and attitudinal factors play a

role in high- and low-achievers

Multilevel modelling: aimed to explore and confirm whether any attitudinal and background variables

(e.g. student motivation, use of the internet, etc.) played a significant role in predicting the language

level of students

Chi-square test of independence: aimed to investigate whether the different variables of interest (e.g.

state, location, gender, etc.) were related to questionnaire responses. Standardised residuals were also

computed to identify which responses were contributing to the test of significance

ANOVA and t-tests: aimed to explore whether there was any variance in the teacher group means for

questionnaire composite measures. Questionnaire statements on similar topics (e.g. assessment

practices, use of English in the classroom, etc.) were grouped together to determine whether teacher

variables (i.e. experience, education, school type, etc.) influenced responses

Thematic analysis in the qualitative strand: focused on bringing the wealth of collected in-depth

observational, questionnaire, interview and descriptive data into general thematic categories which

indicated major issues brought up by the different stakeholders participating in the project.

14

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

The final analysis stage involved an integration of the quantitative and qualitative findings. This was essentially an

expert judgement approach which involved key members of the project team identifying relationships between

the different quantitative and qualitative findings and providing evidence for these relationships.

Ethical guidelines from the University of Cambridge, the British Association of Applied Linguistics and the British

Educational Research Association were followed during all data collection and data analysis phases of this project.

Project timeline

Activity

Date

Cambridge English proposal for the baseline project

submitted to the Ministry of Education

3 February 2013

Gathering of relevant data from the Ministry of

Education

February September 2013

Development of assessment and questionnaire

instruments

February April 2013

Review and analysis of curricula, teaching

documentation, examination data, etc.

February October 2013

Visits to schools for classroom/teacher observations,

Speaking tests, interviews with staff

18 October 1 November 2013

Administration of paper-based benchmarking tests

in schools

29 October 5 November 2013

Receipt and processing of results

November December 2013

Analysis of data and production of reports

January 2014 March 2014

Presentation of findings and recommendations

1 4 April 2014

Limitations

There were several issues that arose during the dispatch, administration and return of the exam materials which

resulted in fewer candidates taking the tests and completing questionnaires than expected or in some data being

removed from the analysis.

Exam/classroom observation administration:

The administration of the Cambridge English exams coincided with the end of term, which resulted in

fewer students in attendance than expected.

For the classes who had not yet taken their exams, the lessons observed tended to focus on exam

preparation, which may not have been indicative of a typical English lesson.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Methodology

15

Missing/incorrect ID data:

Pre-school learners comprise a smaller proportion in the sample than originally planned, due to the

high incidence of missing or incorrect student data in the data files. ID and name information for Preschool children was not provided. The data entered by the children and/or their teachers showed

frequent irregularities which led to some data being discarded.

The proportion of primary and secondary school teachers was more similar in the original sample (41%

primary school classes/teachers and 59% secondary school classes/teachers). However, due to large

numbers of incorrectly completed test sheets for teachers and the absence of such data from the

Ministry of Education for cross-referencing, it could not be determined which school stage some

teachers taught in and as such their data was excluded from the data set.

The number of teachers who completed the language tests (N=424) and teaching knowledge test

(N=600) was smaller than the number expected (N=934). This suggests that some teachers may have

opted out of taking the tests and that the teachers who did complete the tests may have been selfselected (See Section 4 for more information).

Exam malpractice:

During the marking of Writing scripts, examiners noticed many instances of malpractice in that either

pairs of students had the same/similar answer or in some cases the whole class had the same/similar

answer. This was particularly evident for Pre-school classes.

Questionnaires:

The learner questionnaire was intended to be administered to all secondary students and Year 6

students only; however, it was inadvertently included in the test materials sent to Pre-school classes.

Response data from Pre-school students was not included in the analysis because reliability and

accuracy could not be assured.

The proportion of questionnaires returned from each state was also unequal, with Selangor accounting

for 20% of all teacher questionnaires and all learner questionnaires returned. Perlis and WP Putrajaya

accounted for fewer than 1% of all teacher questionnaires returned. WP Labuan and WP Putrajaya

accounted for fewer than 1% of all learner questionnaires returned.

Examination review:

Cambridge English did not receive important statistical data about item and test performance for the

national exam sample question papers. This information would have allowed a far more in-depth

analysis to be carried out.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

16

3.

Key findings

The key findings provide a snapshot of the established learner proficiency baseline and also highlight the most salient

and meaningful differences in proficiency levels which emerged across certain variables as statistically significant, such

as location, gender and class specialisation. In addition, the key findings note the main attitudinal and background

factors which were found to be associated with high performing learners.

Pre-school

On average below CEFR level A1

78% below A1, 22% at A1/A2

Writing and Speaking emerge as weaker skills than Listening and Reading

Year 6

On average at CEFR level A1

32% below A1, 56% at A1/A2, 13% at B1/B2

Similar performance observed across Listening, Reading and Speaking; Writing emerges as the strongest skill

Students in remote and rural areas perform significantly worse than in urban areas

Form 3

On average at CEFR level A2

69% at A1/A2 and below; 30% at B1/B2; 1% at C1/C2

Speaking emerges as the weakest skill

Students in remote and rural areas perform significantly worse than in urban areas

Female students perform significantly better than male learners

Form 5

On average at CEFR level A2

55% at A1/A2 and below; 43% at B1/B2; 2% at C1/C2

Speaking emerges as the weakest skill

Students in remote and rural areas perform significantly worse than in urban areas

Male students perform significantly worse than female students

Students in Science classes perform significantly better than students in other specialisation classes

Form 6

On average at CEFR level A2/B1

41% at A1/A2 and below; 53% at B1/B2; 6% at C1/C2

Listening and Speaking emerge as the weakest skills

Students in remote and rural areas perform significantly worse than in urban areas

Students in Science classes perform significantly better than students in other specialisations

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

17

Role of attitudinal and background variables

Learners at all levels recognise the importance of learning English for improving their employment and

educational opportunities in the future

Learners have very little exposure to English or the opportunity to use English either within the learning

environment or outside it

Learners whose parents speak English are more likely to be performing better in school

Learners in rural and remote schools are less likely to be highly motivated or have parents who speak English

when compared to their urban counterparts

Note: Percentages may not always add up to 100% due to rounding.

As noted in the Methodology section in this report, the language tests used to benchmark the students (and

teachers) tapped into both receptive language skills Listening and Reading and productive skills Writing and

Speaking. The use of a suite of tests which are based on a communicative construct of language ability was an

important aim of the project, in order to allow a more comprehensive and valid profile of language proficiency to

be built. The need to gather a broad range of data about language proficiency, instead of just relying on easy-toadminister reading and listening tests, is also emphasised in the CfBT Education Trust Commentary on the

Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 (McAleavy, Hamilton and Latham no date:12).

We now move on to an overview of the national baseline at the school grades of interest and supplement the test

findings with the key insights obtained from the questionnaires, interviews and classroom observations.

Overall national profile

Question 1: How do students at different school stages in the Malaysian states/federal territories perform on a

set of Cambridge English language tests overall and by skill (Reading, Writing, Listening, Speaking) against the

CEFR?

Language proficiency: Primary school

Pre-school

Overall, Pre-school learners in Malaysia achieved a CEFR level below A1. In terms of the language skills of Reading,

Writing, Listening and Speaking, all four skills were found to be below CEFR level A1, as can be seen in Table 3.1.

The CEFR levels in the table are based on the mean scores of the Pre-school cohort, and for Listening and Reading,

the Pre-school children achieved a mean score just below the A1 level boundary, indicating that their productive

skills of Speaking and Writing in English lag behind their receptive Listening and Reading skills. This could partly be

a reflection of the slower development of literacy in young learners, who often lack the skills to handle the

cognitively complex processes of writing in both their first and additional languages (Bangert-Drowns, Hurley and

Wilkinson 2004). It is also in line with the trend found in many learners for receptive skills to be stronger than

productive ones.

Table 3.1 Average CEFR proficiency levels: Pre-school

Language skill

Listening

Reading

CEFR level

Below A1

Below A1

Writing

Speaking

Below A1

Below A1

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

18

The distribution of Pre-school learners across the different CEFR levels covered in their tests (Table 3.2 and Figure

3.1) ranged from A2 to below A1. In all four skills, the largest proportion of Pre-school children were below level

A1, but as noted above, Speaking and Writing appear to be weaker than Reading and Listening: in the case of

Listening and Reading, approximately a third to a half achieved either level A1 or A2 (32% for Listening and 44%

for Reading), in the case of Speaking and Writing that proportion was much smaller (12% for Writing and 3% for

Speaking).

Table 3.2 Distribution of CEFR levels: Pre-school

Language skill

Listening

Reading

A2

9%

11%

Writing

4%

Speaking

0%

Overall

6%

A1

23%

33%

8%

3%

16%

Below A1

68%

56%

89%

97%

78%

Note: Overall percentage is based on the equal distribution of all four skills. Percentages may not always add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 3.1 Distribution of overall CEFR levels: Pre-school

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Below A1

A1

A2

Year 6

Overall, Year 6 learners in Malaysia achieved a CEFR level A1. Listening, Reading and Speaking were observed to be

at A1, with Writing performance at level A2 (Table 3.3). However, the mean score which the CEFR Writing level is

based on corresponds to a low A2 level, making the four skills generally comparable in development.

Table 3.3 Average CEFR proficiency levels: Year 6

Language skill

Listening

Reading

CEFR level

A1

A1

Writing

Speaking

A2

A1

The range of CEFR levels across Year 6 can be seen in Table 3.4 and Figure 3.2, which indicate that the

performance of most Year 6 students spans CEFR levels B1 to below A1. Compared to Pre-school learners, Year 6

learners show a smaller proportion at level A1 and below (94% at Pre-school, 66% at Year 6), and a larger

proportion at the higher A2 level, with some achieving B1 as well. The gap between the high and low achievers in

Year 6 is worth noting, as it signals that a variation in learning gains is already present at the end of primary

school, and will increase further in Form 3 and Form 5, as will be seen later.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

Table 3.4 Distribution of CEFR levels: Year 6

CEFR level

Listening

Reading

Writing

Speaking

Overall

B2

0%

0%

2%

0%

1%

B1

10%

0%

31%

5%

12%

A2

20%

14%

33%

20%

22%

A1

28%

29%

19%

59%

34%

Below A1

42%

57%

14%

16%

32%

19

Note: Percentages may not always add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 3.2 Distribution of Overall CEFR levels: Year 6

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

Below A1

A1

A2

B1

B2

Attitudinal and background factors: Primary school

In order to better understand the context of learning and teaching in Malaysia, students were asked to complete a

questionnaire. The focus of the questionnaire was on learners attitudes toward learning and background factors

which may play a role in learner motivation, with the aim being to identify key factors which may be associated

with high achievement in English language learning. Due to the young age of the Pre-school learners, it was not

deemed appropriate to ask them to complete a questionnaire. There is widespread consensus that questionnaires

are not generally given to children under the age of 8 because they are still at an early stage of their linguistic and

cognitive development, which can make it difficult to ensure the validity and reliability of their responses (Borgers,

Leeuw and Hox 2000). As such, this section focuses on Year 6 only.

Questionnaires were completed by 4,956 Year 6 students (29% of the returned student questionnaires) and by

443 teachers who indicated that they have the most experience teaching Year 6 learners (35% of teacher

questionnaires). The key findings from the questionnaires which emerged as significant and meaningful are

summarised below. The data analysis procedures for the questionnaires can be found in the Cambridge Baseline

2013 Technical Report.

Attitudes towards learning English

The academic literature on second/foreign language acquisition has indicated that learners attitudes towards

learning a language and the extent to which they perceive the language to be useful can influence learner

behaviour, both in terms of the amount of effort exerted on language learning and the extent to which they

persist with learning it (Csizr and Drnyei 2005; Gardner 1985; Oxford and Ehrman 1993). This was, as such, an

important construct captured in parts of the questionnaire in this project.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

20

Fifty percent of Year 6 learners strongly agreed that learning English is important to them; however, this figure

was lower than all other grades (see Figure 3.3), possibly because unlike secondary school learners they have less

experience of the world and are further away from making choices about further study or work. Figure 3.3 also

shows that primary school students were more likely than secondary school students to strongly agree when

asked if they enjoy their English lessons at school. This may be linked to the level of difficulty of their lessons as

the lower level of proficiency of Year 6 students means that their lessons likely focus on simple grammatical

structures and vocabulary, whereas the older leaners are facing more cognitively demanding lessons as their

language ability increases. The secondary school students are also preparing for exams which have a more direct

impact on their future plans, perhaps influencing their level of enjoyment.

Figure 3.3 Importance and enjoyment of English by grade (percentage who strongly agree)

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Year 6

Form 3

Learning English is important

Form 5

Form 6

I enjoy English lessons

Several statements in the questionnaire were designed to shed further light on the motivational factors that may

be influencing learners language learning behaviour such as instrumentality or milieu (Gardner 1985).

Instrumental motivation refers to the utilitarian benefit or incentives associated with learning a language such as

getting a job, a place in university, travelling or using the internet, whereas the motivational dimension of milieu

refers to the influence of learners immediate social environment (i.e. parents, family and friends), excluding

teachers, in shaping their attitudes to learning. Learners who perceive family support for language learning are

more likely to persist with it and more willing to work harder at it (Colletta, Clment and Edwards 1983; Gardner

1985). Figure 3.4 shows that Year 6 learners did recognise the functional purpose of English, as 73% of these

learners reported that it is very important for them to learn English as it will help them get into a good university

and 69% reported that it is very important as it will help them get a good job. These learners were also more likely

than the students in all other grades to say that it is very important for them to learn English to please their

parents (53%) (Form 3: 36%; Form 5: 34%; Form 6: 22%).

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

21

Figure 3.4 Reasons for learning English: Year 6

How important are these reasons for you? Learning English will...

help me get into a good

university.

help me get a good job.

Very important

make it easier for me to travel

to other countries.

Important

Not very important

please my parents.

Not at all important

make it easier for me to talk

to other people.

.help me use the internet to

get information.

Not sure

0%

20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

These findings suggest that Year 6 learners are primarily motivated to learn English for instrumental reasons, and

to a lesser extent but likely a very important reason, to please their parents. Although neither motivational

dimension is causally linked to learner outcomes because other variables such as instructional quality, learning

opportunities and learner ability also play a crucial role, they do provide an indication of how much energy or

attention learners are willing to expend on learning. However, despite these indications that learners are

motivated to learn English, only 11% of teachers strongly agreed that they thought their Year 6 students enjoyed

their English lessons and several teachers commented in the open-response questions that they thought students

were unmotivated and lacked interest in learning English:

Students have no background in English and have no interest (Rural primary school teacher, Sarawak)

This point was also mentioned by Heads of Panel/Head Teachers:

The students are not interested in learning English (Urban primary school teacher, Melaka)

During post-observation interviews, some teachers felt that parents could do more to support and motivate their

children. Teachers were asked in the questionnaire whether their students parents participate actively in their

education and 45% of primary school teachers either disagreed or strongly disagreed with this question. Teachers

did recognise though that perhaps parents, particularly those in rural areas, may not have the skills or knowledge

to provide this support and that the Ministry may need to take on the responsibility of helping parents in this area:

Support and encouragement from parents can help. Education Ministry should have a series of

motivational courses for parents from rural areas to expose the importance of English to them (Rural

primary school teacher, Melaka)

Have seminars for parents to create awareness about the importance of mastering the language (Urban

primary school teacher, Sarawak)

22

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

Teachers see the value of involving parents in their childrens education; however, ensuring parents have the

information and skills to do this may be a necessary first step.

Exposure to English

It is a widely accepted premise both in the theoretical and practical language learning domains that exposure to a

foreign language within the learning environment and/or the home environment plays a positive role in learning.

The European Survey on Language Competences (ESLC) found that greater use of English, by both students and

teachers, in the classroom was positively related to language ability (Jones 2013). The ESLC also found that

parents knowledge of the foreign language being studied and leaners exposure to it in the home or community

was positively related to learner outcomes (Jones 2013). Therefore, in the questionnaire, we investigated the

extent to which leaners are exposed to English either in their home environment or at school.

Approximately 50% of Year 6 students reported that their parents speak English either very well or moderately

well and 38% take English lessons outside school, which is the highest percentage for all grades (Form 3: 26%;

Form 5: 21%; Form 6: 10%). However, despite this, a majority of these students said that they either never speak

English or do not speak English very often outside school, which includes with family or friends (56%) or in the

wider community (74%). Figure 3.5 shows the frequency of English language usage for different activities that

young people are likely to engage in.

Figure 3.5 Frequency of English language usage for different activities: Year 6

Outside of school

I use the internet in English including

playing games.

I watch TV of films in English.

Very often

Sometimes

I read books or comic books in English.

Not very often

I speak English with my family and/or

friends.

Never

Not sure

I speak English to people in my

village/town/city.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

As learners do not appear to be using English very often in their home environment, the use of English within the

learning environment becomes even more important to their language development. Only 55%, the lowest

percentage of all grades, said that their teacher speaks English very often during lessons (Form 3: 75%; Form 5:

79%; Form 6: 90%). Comments in the teacher questionnaire suggest that too much instruction may be taking place

in the learners first language:

The headmaster should ensure that teaching and learning English must be done in English. Sometimes

when people visit it's in English, otherwise they teach in their mother tongue There should be more focus

on using English during teaching and learning in class (Rural primary school teacher, Perak)

English teachers should speak English during lessons (Urban primary school teacher, Kedah)

This finding could relate to teacher language proficiency, as 13% of primary school teachers as compared to 4% of

secondary school teachers reported that they speak the local language a lot during lessons because they do not

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

23

feel confident teaching in English. The teacher test data, to be discussed in Section 4, will show that primary

teachers language ability is lower than that of secondary school teachers. However, the relatively low percentage

of English usage in the classroom could also be linked to teachers perceptions of their learners language ability.

Some teachers admit that they do not speak English during lessons because they do not believe learners are able

to cope with instruction which is completely in English:

Lessons cannot be fully conducted in English as students dont understand (Rural primary school

teacher, Perlis)

This finding is worrisome because it suggests that teachers may not be fully aware of how to grade their language

so that it is comprehensible for their learners. Observation findings indicate that this is an issue for some teachers

(see Section 4).

Turning to the learners use of English, they reported that they do not use English that often during English lessons

either, whether it is with their teacher or with their classmates (see Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6 Use of English in the classroom: Year 6

During English lessons...

my teacher speaks English.

Very often

Sometimes

I speak to the teacher in English.

Not very often

I speak to other students in

English.

Never

Not sure

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

The limited use of English in the classroom could be related to the type of learning activities chosen by teachers,

and mentioned by observers, such as drilling, reading aloud, etc., which do not give learners opportunities to use

English communicatively (see Section 4). The observers also noted a propensity for teacher-dominated lessons

which also tends to reduce the amount of English produced by learners.

Beyond the classroom, the school environment can also influence students motivation to learn English by

providing opportunities to practise English outside the classroom and by showing support for English learning.

Thirty-five percent of primary school teachers strongly agreed that their school has created an English

environment outside the English classroom, but they did comment that the school could do more:

Expose students to more English, e.g. through English charts and labels around the school compound

(Urban primary school teacher, Kelantan)

Despite the fact that Year 6 learners do not appear to have much exposure to English either within or outside the

classroom, 40% of them strongly agreed that they would like to learn other subjects in English, such as Maths or

Science. This point was also made by several teachers, in response to the open-ended questions; they feel that

learners would benefit from Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL):

Teaching and learning in English for subjects like Science and Mathematics can have a positive impact.

This can help the students improve their understanding of the English language (Urban primary school

teacher, Johor)

24

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

Other suggestions frequently made by teachers to improve English learning in their school related to reducing the

number of students in each class and increasing the number of contact hours in English:

Reduce the number of students in the classroom to about 20 or 25 (Urban primary school teacher,

Pahang)

The time allotted for English is insufficient (Urban primary school teacher, Melaka)

Research suggests that large class sizes can reduce the likelihood that teachers will actively encourage student

participation, because there is a tendency for them to be more concerned with controlling student behaviour

(Fuller and Kapakasa 1991). Therefore, to ensure that students are given opportunities to use English in the

classroom, it may be necessary to further investigate optimal class sizes.

The suggestion to increase the number of English contact hours could also be explored further. A review of the

Malaysian educational system by UNESCO found that the curriculum was overcrowded and that many student

competencies may not be fully developed as a result (2013:7). It may be worth considering whether it is feasible

for schools that are struggling to meet English language targets to reduce their curricular offerings in order to

increase lesson time for core subjects like English until they reach the expected learning outcomes. This would

require the national curriculum to be structured into a core component and an optional component in order to

allow schools some flexibility to focus attention on the needs of their students. This has been found to lead to

improvements in learning (Chapman et al 2005 and Wagner et al 2006). However, it is important to point out that

both of these suggestions will only lead to improved learner outcomes if other factors, such as school leadership,

instructional quality, the curriculum, etc. are improved at the same time.

Learner perceptions of their language ability

Learners beliefs about their own capacity to learn, often referred to as self-efficacy, have been found to be

positively associated with academic outcomes (Mills, Pajares and Herron 2006; Multon, Brown and Lent 1991).

Self-efficacy centres on the belief that one is capable of learning. In order to investigate this construct, learners

were asked about the perceived difficulty of their lessons and their strengths and weaknesses in English, as these

can both be an indication of linguistic self-confidence (Clment, Gardner and Smythe 1977; Wesely 2012).

Sixty-four percent of Year 6 students reported that their English lessons were at the right level of difficulty but

15% said they were too easy and 11% said they were too hard. This suggests that learners generally feel that they

are able to cope with their lessons and succeed at the tasks they are given. When asked about their strengths and

weaknesses in English, Year 6 students believed that Reading was their strongest skill followed by Listening,

whereas they indicated that Speaking was their weakest skill (see Table 3.5). When teachers were also asked

about their learners strengths and weaknesses they agreed with their students self-assessment (see Table 3.5).

However, the test data suggests that learners may be performing slightly better in Writing than they think

(performance in Writing was at level A2, with the other skills at A1). Year 6 students overwhelmingly want to

improve their Speaking skills (40%).

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

25

Table 3.5 Learners strengths and weaknesses in English: Learner and teacher perceptions

Weaknesses

Strengths

Skill/system

Learners: Year 6

Teachers: Year 6

Learners: Year 6

Teachers: Year 6

Listening

21%

26%

7%

5%

Reading

29%

54%

10%

2%

Writing

13%

10%

23%

33%

Speaking

7%

3%

27%

42%

Vocabulary

2%

4%

10%

10%

Grammar

Not sure

4%

3%

9%

8%

24%

0%

14%

0%

Note: Percentages may not always add up to 100% due to rounding.

An interesting finding related to learners perceptions of their strengths and weakness is the number who selected

Not sure when asked about their strength (24%). The frequent selection of Not sure could indicate an issue with

either their language learning awareness, their confidence as language learners or it could be linked to a sense of

modesty, related to cultural values associated with a collectivist society. A combination of these factors may be

the likeliest explanation because when students were asked about their worst skill in English, only 14% of them

selected Not sure which could indicate that they are more willing to state their weaknesses or are more focused

on them than their strengths. However, the percentage who did select Not sure for their weaknesses is still quite

high when compared to other questions. It may be that Year 6 learners lack some awareness of their English

language ability. This could be expected of primary school learners who may have limited knowledge about

language.

Discussion

English language education in primary school is critical not only because it is where learners are taught the basics

of English (i.e. grammar and vocabulary) but also because it is during this school stage that children are going to

decide whether they like English and are capable of learning it. If children have negative learning experiences, it

could impact their future learning. Many secondary school and Year 6 teachers complained in the questionnaires

that they felt students were not being adequately prepared in the lower grades, which they associated with the

number of non-optionist teachers in primary school. As two teachers put it:

Obtain an English optionist teacher to teach the Pre-school level to ensure theyre taught the basics

correctly (Urban primary school teacher, Perak)

Students should have a strong foundation in English in primary school before moving to secondary school

(Rural secondary school teacher, Sabah)

Questionnaire findings do also suggest that non-optionist teachers are less confident than optionist teachers in a

number of areas, such as planning English lessons, using English in the classroom and assessing their students, (see

Section 4 for more detail). However, teacher shortages may not make it feasible to hire only optionist teachers.

Therefore, upskilling of current teachers by providing specialist training becomes even more essential.

Ministry policy planners had expressed the hope that by the end of primary school, students would have achieved

level B1. Although 13% of Year 6 learners are at B1 or above, the majority of students are A1 and below. The

desire to achieve B1 by the end of primary is perhaps ambitious when one considers that many European

countries target either A1 or A2 as the expected minimum by the end of primary school (Eurydice 2012). The

conditions for learning English are somewhat more conducive in Europe because of the presence of the language

in many aspects of daily culture, yet the ESLC results show that only in Sweden, Malta and Belgium do at least 80%

of learners achieve B1 or above by the end of lower secondary (Jones 2013). It is clear from the questionnaire data

26

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

that Malaysian learners in primary school are facing challenges particularly related to their exposure to English,

both within the learning environment but also in the home environment which their European counterparts are

facing to a lesser extent. The variation in performance across Year 6 indicates that a phased approach may be

necessary to achieve higher levels of English language ability at the end of primary school, which takes into

consideration realistic targets achieved over several phases. More detailed recommendations will be discussed in

Section 6.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

27

Language proficiency: Secondary school

Form 3

Overall, Form 3 learners in Malaysia achieved a CEFR level A2, as seen in Table 3.6. As observed with Pre-school

and Year 6 learners, Speaking performance was weaker, at CEFR level A1.

Table 3.6 Average CEFR proficiency levels: Form 3

Language skill

Listening

Reading

CEFR level

A2

Writing

Speaking

A2

A1

A2

The range of CEFR levels achieved by the majority of Form 3 learners (Table 3.7 and Figure 3.7) spans CEFR levels

B2 to below A1. Speaking presents the weakest profile, with relatively more students at the lowest A1/A2 levels

and below than any of the other skills (84% at Speaking, 67% at Reading, 64% at Listening, 64% at Writing).

The range in CEFR levels observed at Form 3 is a striking finding, since this range in CEFR levels represents learners

who are very basic beginners to independent upper intermediate learners, and signals that the differentiation in

language proficiency, which started to become apparent at the end of primary school, where the span of levels for

Year 6 was B1 to below A1, has increased by one CEFR level to span levels B2 to below A1. The achievement gap is,

therefore, widening in secondary school. This may be because less equitable exposure to factors which contribute

to language learning (e.g. exposure to the language, the internet, books in English) is starting to make a stronger

impact among those secondary school learners who have access outside school to such an enabling environment

than among those learners who do not. The questionnaire data supports this supposition, and a full discussion of

the attitudinal and background variables for all secondary school students will be presented at the end of this

section.

Table 3.7 Distribution of CEFR levels: Form 3

Language skill

Listening

Reading

Writing

Speaking

Overall

C2

0%

0%

0%

1%

0%

C1

0%

0%

1%

1%

1%

B2

21%

13%

14%

4%

13%

B1

16%

20%

21%

11%

17%

A2

23%

45%

27%

21%

29%

A1

30%

16%

10%

56%

28%

Below A1

11%

6%

27%

7%

12%

Note: Percentages may not always add up to 100% due to rounding.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

28

Figure 3.7 Distribution of Overall CEFR levels: Form 3

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

Below A1

A1

A2

B1

B2

C1

C2

Form 5

On average, Form 5 learners in Malaysia achieved a CEFR level A2, as seen in Table 3.8. Despite achieving the same

CEFR level across all skills, the mean scores the CEFR levels are based on indicate that learners are stronger in

Listening and Reading compared to Writing and Speaking.

Table 3.8 Average CEFR proficiency levels: Form 5

Language skill

Listening

Reading

CEFR level

A2

A2

Writing

Speaking

A2

A2

Form 3 learners were also found to be on average at CEFR level A2 (Table 3.6); however, taking mean scores and

distribution of CEFR levels into account, Form 5 students displayed higher proficiency as a cohort compared to

their Form 3 counterparts and the learners at the lowest levels of language proficiency (A1 and below) are smaller

in proportion in Form 5.

The range of overall CEFR levels achieved by Form 5 students (Table 3.9 and Figure 3.8) spans below A1 to C1.

Similar to the performance of other school grades reported so far, speaking presents a slightly weaker profile, with

relatively more students at the lowest A1/A2 levels and below than any of the other skills (65% for Speaking, 57%

for Reading, 55% for Listening; 45% for Writing).

Table 3.9 Distribution of CEFR levels: Form 5

Language skill

Listening

Reading

Writing

Speaking

Overall

C2

0%

0%

0%

1%

0%

C1

0%

0%

2%

4%

2%

B2

26%

20%

9%

11%

17%

B1

18%

23%

45%

19%

26%

A2

24%

41%

27%

24%

29%

A1

25%

13%

Below A1

6%

3%

18%

31%

10%

27%

Note: The percentages observed for Writing are combined at levels A1 and below because the Writing test which was given to Form 5

cannot reliably distinguish between these two levels and they are, therefore, reported together. Percentages may not always add up to

100% due to rounding.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

29

Figure 3.8 Distribution of Overall CEFR levels: Form 5

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

A1 and

Below A1

A2

B1

B2

C1

C2

Form 6

On average the majority of Form 6 learners in Malaysia achieved a level spanning A2 and B1, as seen in Table 3.10.

Compared to Form 5, they performed similarly in Listening, and better in Reading, Writing and Speaking in terms

of average score.

Table 3.10 Average CEFR proficiency levels: Form 6

Language skill

Listening

Reading

CEFR level

A2

B1

Writing

Speaking

B1

A2

Table 3.11 and Figure 3.9 show that the range of CEFR levels achieved by the majority of Form 6 students (80%)

spans levels A2 and B2, with Speaking showing a weaker profile (31% were found to be at level A1 and below for

Speaking, compared to 17% for Listening, 5% for Writing and 2% for Reading), which is in line with findings for the

other school grades. It is worth noting that the variation in language proficiency found for Forms 3 and 5 is not as

pronounced at Form 6, possibly due to the fact that Form 6 students are self-selecting and more motivated to

succeed academically, including in English, and therefore present a more homogenous group. The smaller

differentiation in achievement could also be as a result of the previous national policy to teach Science and Maths

in English, which is no longer in effect, but is likely to have contributed to the language proficiency of Form 6

learners.

Table 3.11 Distribution of CEFR levels: Form 6

Language skill

Listening

Reading

Writing

Speaking

Overall

C2

4%

1%

2%

0%

2%

C1

6%

1%

5%

5%

4%

B2

13%

16%

43%

13%

21%

B1

18%

44%

39%

27%

32%

A2

43%

35%

8%

24%

27%

A1

13%

2%

Below A1

4%

0%

5%

15%

16%

14%

Note: The percentages observed for Writing are combined at levels A1 and below because the Writing test which was given to Form 6

cannot reliably distinguish between these two levels and they are, therefore, reported together. Percentages may not always add up to

100% due to rounding.

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

30

Figure 3.9 Distribution of Overall CEFR levels: Form 6

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

A1 and

Below A1

A2

B1

B2

C1

C2

Attitudinal and background factors: Secondary school

Questionnaires were completed by 4,740 Form 3 learners (28% of all student questionnaires), 5,495 Form 5

learners (32%), 1,913 Form 6 learners (11%) and by 738 secondary school teachers (57% of all teacher

questionnaires). The grades in which teachers indicated they have the most experience teaching are as follows:

Form 3 305, Form 5 330 and Form 6 87. The key findings which emerged as significant and meaningful are

summarised below for all secondary students.

Attitudes towards learning English

As discussed in the Year 6 section, learners attitudes towards learning a language and their reasons for learning it

can shed light on their motivation and ultimately provide insight into the level of effort they are willing to expend

on language learning (Csizr and Drnyei 2005; Gardner 1985; Oxford and Ehrman 1993). The secondary school

leaners recognise the importance of learning English and the majority of them strongly agreed with the statement

Learning English is important to me (Form 3: 54%; Form 5: 61%; Form 6: 64%). They also appear to be very aware

of the importance of English for employment, university entrance and travel (see Figure 3.10). The secondary

school learners were less likely than Year 6 students to report that it was very important for them to learn the

language to please their parents (Year 6: 53%, Form 3: 36%, Form 5: 34%, Form 6: 22%) suggesting that parental

pressure eases off as learners become older. However, teachers noted that parents can still play an important role

in their childrens education, but that they may need support in order to do this successfully:

Parents should be counselled and taught easy teaching techniques to help their children at home. Most

have no guidance at home and cannot focus in class (Urban secondary school teacher, Selangor)

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

31

Figure 3.10 Reasons for learning English: Secondary school students

How important is each of these reasons for you? Learning English will...

help me get into a good

university.

help me get a good job.

Very important

make it easier for me to travel.

Important

make it easier for me to talk to

other people.

Not very important

Not at all important

.help me use the internet to get

information.

Not sure

please my parents.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

The findings presented above suggest that secondary school learners are primarily motivated to learn English for

instrumental reasons such as getting a good job, a place in a good university or for travel. However, we also find

that secondary students are showing a slightly stronger tendency than primary school students to report that they

are interested in learning English out of cultural interest or interest in English media. Clment, Drnyei, Noels

(1994) and Csizr and Drnyei (2005) describe this dimension of motivation as relating to learners interest in the

cultural products or media associated with the second language. Secondary school learners are more likely than

primary school students to report that it is very important to learn English to use the internet (53%) and teachers

also reported that they are interested in English music and TV:

Students enjoy watching English movies and listening to English songs (Urban secondary school

teacher, Pahang)

Although these learners seem to be motivated to learn, they were less likely than Year 6 learners to strongly agree

that they enjoy their English lessons at school (Secondary: 31%, Year 6: 43%). This may be attributable to the

increasing difficulty of their lessons as they progress from one grade to the next and/or to a more prominent focus

on passing exams. Some teachers also raised a concern about the number of courses students are required to take

in secondary school:

Students are confused as there is too much content and too many subjects for them to learn. An

overambitious syllabus confuses students leading to a haywire situation (Urban secondary school

teacher, Terengganu)

When secondary school teachers were given the statement My learners like learning English, only 5% of them

strongly agreed while 29% either disagreed or strongly disagreed. Secondary school teachers, like their primary

counterparts, consistently commented in the questionnaire open fields and during post-observation interviews

that they thought learners were unmotivated and do not perceive English as important:

My students lack motivation because English is not a necessity in their lives (Rural secondary school

teacher, Perak)

Students are not interested in English because they havent realised its importance (Urban secondary

teacher, WP Kuala Lumpur)

32

Cambridge Baseline 2013

Student English language proficiency

There appears to be a disconnect between what learners are reporting and their teachers perceptions of their

motivation. One possible consequence of this is that teachers may not be taking advantage of what is actually

motivating their students when they plan their lessons. Learning how to take advantage of learner motivation may

be a useful feature in any future teacher upskilling programmes.

Exposure to English

Learners exposure to English in school and outside school plays an important role in learning. When teachers