Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Influence of Mechanical Bowel Preparation

Încărcat de

Faisol KabirDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Influence of Mechanical Bowel Preparation

Încărcat de

Faisol KabirDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The American Journal of Surgery (2015) 210, 106-110

Clinical Science

The influence of mechanical bowel preparation

on long-term survival in patients surgically

treated for colorectal cancer

Hans Pieter vant Sant, M.D.a,*, Arnoud Kamman, M.D.a,

Wim C. J. Hop, Ph.D.b, Martijn van der Heijden, M.D.a,

Johan F. Lange, M.D., Ph.D.c, Caroline M. E. Contant, M.D., Ph.D.d

a

Department of Surgery, Ikazia Hospital, Montessoriweg 1, 3083 AN Rotterdam, The Netherlands;

Department of Biostatistics, cDepartment of Surgery, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam,

The Netherlands; dDepartment of Surgery, Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

KEYWORDS:

Survival;

Colorectal cancer;

Surgery

Abstract

BACKGROUND: In this study, we evaluated long-term survival in patients treated with and without

mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) before colorectal surgery for cancer.

METHODS: Long-term outcome of patients of 2 main participating hospitals in a prior multicenter

randomized trial comparing clinical outcome of MBP versus no MBP was reviewed. Primary endpoint

was cancer-related mortality and secondary endpoint was all-cause mortality.

RESULTS: A total of 382 patients underwent potentially curative surgery for colorectal cancer. One

hundred seventy-seven (46%) patients were treated with MBP and 205 (54%) were not before surgery.

Median follow-up was 7.6 years (mean 6.6, range .01 to 12.73). There was no significant difference in

both cancer-related mortality and all-cause mortality in patients treated with MBP and without MBP (P

5 .76 and P 5 .36, respectively). Multivariate analysis, taking account of age, sex, AJCC cancer stage,

and ASA classification, also showed no survival difference.

CONCLUSIONS: Our results indicate that MBP does not seem to influence long-term survival in patients surgically treated for colorectal cancer.

2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

There were no relevant financial relationships or any sources of support

in the form of grants, equipment, or drugs.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Trial registration number for the randomized clinical trial this article

derived from was NCT00288496.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 131-633332710; fax: 131-102975130.

E-mail address: hpieter44@hotmail.com

Manuscript received January 29, 2014; revised manuscript October 4,

2014

0002-9610/$ - see front matter 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.10.022

Traditionally, mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) was

believed to clean the colon and rectum from residual fecal

contents and lower the bacterial load to prevent anastomotic failure and reduce postoperative infectious complications.1 To date, however, there is significant evidence that

questions the beneficial effects of MBP. Recent systematic

reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials

have shown no evidence that MBP is associated with

reduced rates of anastomotic leakage or septic complications after elective colorectal surgery.24 Most studies

H.P. vant Sant et al.

MBP and survival for colorectal cancer

only evaluated the effects of MBP on short-term outcomes

and studies on the effects of long-term outcomes are scarce,

especially cancer related. At present, there is strong

evidence that postoperative complications influence the

long-term outcome and survival in patients with colorectal

cancer. Patients confronted with anastomotic leakage have

poorer long-term cancer-specific survival rates.57 In this

study, we tested the hypothesis that MBP has no positive influence on cancer-specific long-term survival (.6 years) after colorectal cancer surgery as MBP is not associated with

reduced anastomotic leakage rates in literature.

Methods

This study is a subgroup analysis of a prior large

multicenter randomized clinical trial published by Contant

et al.8 They enrolled 1,354 patients from 1998 to 2004 and

randomized between MBP and no MBP before elective

colorectal surgery and compared the incidence of anastomotic leakage and septic complications. Patients randomized for MBP received 2 to 4 l of polyethylene glycol

bowel lavage solution (***Klean Prep) in combination

with ***bisacodyl (11 hospitals) or sodium phosphate solution (2 hospitals). Exclusion criteria were an acute laparotomy, laparoscopic colorectal surgery, contraindications for

the use of MBP, an a priori diverting ileostomy, and age

less than 18 years old.

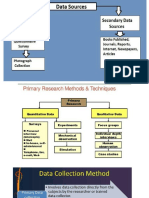

In the present subgroup analysis, 382 patients of 2 main

participating hospitals in the previously mentioned randomized trial were selected by the criteria of having

undergone potentially curative elective colorectal surgery

for cancer (Fig. 1). Clinical data were obtained through the

previous study by Contant et al8 with permission and linked

to death records to create a novel dataset. Death records up

to December 31, 2010 were obtained. The diagnosis of

colorectal cancer was confirmed by pathology reports. Cancer stage was determined through pathology reports, radiology reports, and clinical audit records. Our primary

Figure 1

107

endpoint was cancer-related mortality and secondary

endpoint was all-cause mortality.

Statistical analysis

KaplanMeier curves for overall and colon cancerspecific survival and log-rank tests were used to compare

the MBP arms. In the calculation of cancer-specific

survival, the survivals*** of patients who had died because

of other causes were considered censored*** survival

times. As the large majority of deaths were because of

cancer and there were only a few patients who had died

from an unknown cause, the latter patients were considered

to have died from cancer. Cox-regression analysis was used

to assess the independent effect of various putative

prognostic factors (age, sex, cancer stage, and ASA

classification) besides MBP. Analysis was by intention-totreat. Two-sided P value of less than .05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

Data were collected from 382 patients retrospectively.

Patient selection is shown in Fig. 1. One hundred seventyseven (46%) patients were treated with MBP before surgery

and 205 (54%) were not. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1 and were well balanced between

treatment groups. Overall median follow-up was 7.6 (mean

6.6, range .01 to 12.73) years. Median follow-up for MBP1

was 7.8 (mean 6.8, range .01 to 12.6) and for MBP2 was

7.4 (mean 6.4, range .01 to 12.7). One hundred ninetythree patients deceased during follow-up. Cancer-related

deaths occurred in 128 patients. Noncancer-related deaths

occurred in 48 patients. In 17 patients, the cause of death

could not be discovered. There was no significant difference in both overall mortality and cancer-related mortality

in patients treated with MBP and without MBP before elective colorectal surgery for cancer (log-rank test, P 5 .36

Organization chart for patient selection.9

108

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 210, No 1, July 2015

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of 382 patients undergoing

elective surgical treatment for colorectal cancer

Sex

Male

Female

Age (years)

%60

6170

.70

Cancer stage*

I

II

III

IV

ASA classification

I

II

III/IV

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Radiation therapy

MBP2

(n 5 205)

MBP1

(n 5 177)

98 (48%)

107 (52%)

91 (51%)

86 (49%)

50 (24%)

70 (34%)

85 (42%)

42 (24%)

56 (32%)

79 (44%)

34

98

55

18

(16%)

(48%)

(27%)

(9%)

35

77

51

14

(20%)

(43%)

(29%)

(8%)

57

113

35

47

12

(28%)

(55%)

(17%)

(23%)

(6%)

39

116

22

32

18

(22%)

(66%)

(12%)

(18%)

(10%)

ASA 5 American Society of Anesthesiologists; MBP 5 mechanical

bowel preparation.

*Colon and rectum cancer stage according to the American Joint

Committee on Cancer.

and P 5 .76, respectively; Fig. 2). Thirty-day mortality for

the groups with and without MBP was 4.0% (7/177) and

2.4% (5/205), respectively (P 5 .58).

Cancer-specific survival at 5- and 10 years in the MBP1

arm was 67% (64% standard error) and 59% (64%),

respectively. In the MBP2 arm, these figures were 68%

(63%) and 60% (64%), respectively (Fig. 2).

Overall survival at 5- and 10 years in the MBP1 arm

was 64% (64%) and 54% (64%), respectively. In the

MBP2 arm, these figures were 62% (63%) and 47%

(64%), respectively (Fig. 2).

Also within the separate cancer stages, there were no

significant differences in overall and cancer-specific survival between the MBP arms (all P . .31). Cox-regression

analysis, allowing for age, sex, cancer stage, and ASA classification, also showed no significant differences between

the 2 MBP arms (Table 2). Further extension of the Cox

models with interaction terms to investigate whether the

baseline characteristics influenced the difference between

the 2 MBP arms showed no significant effect of any of

the characteristics. Also, the treatment center did not affect

the survival outcomes.

Postoperative complication rates between patients

treated with and without MBP are shown in Table 3.

Comments

Sufficient evidence has shown that anastomotic leakage

is associated with a higher prevalence of local recurrence

and diminished long-term survival after elective colorectal

cancer surgery.57 Recent meta-analysis and systematic reviews show no difference in anastomotic leakage rates

comparing MBP versus no MBP. Only Slim et al9 published

a meta-analysis in 2004 and found significantly more anastomotic leakage after MBP (5.6% vs 3.2%, P 5 .032).

However, a more recent meta-analysis also by Slim et al

invalidate this outcome having added 2 large randomized

Figure 2 KaplanMeier survival curves for OS and CaS for patients treated with and without MBP before elective colorectal surgery for

cancer. CaS 5 cancer-specific survival; OS 5 overall survival.

H.P. vant Sant et al.

MBP and survival for colorectal cancer

109

Table 2 Multivariate analyses of various factors in relation to cancer-related and all-cause mortality after elective colorectal resection

for cancer

Cancer-related mortality

MBP

No

Yes

Sex

Female

Male

Age

%60

6170

.70

Cancer stage

I

II

III

IV

ASA classification

I

II

III/IV

All-cause mortality

Hazard ratio

95% CI

P value

Hazard ratio

95% CI

P value

1.00

.94

.671.32

.73

1.00

.81

.611.09

.16

1.00

1.14

.811.61

.46

1.00

1.23

.911.65

.17

1.00

1.10

2.77

.641.91

1.594.84

.73

,.001

1.00

1.28

2.56

.802.05

1.604.11

.30

,.001

1.00

2.67

6.91

41.01

1.205.91

3.1215.28

17.6095.58

.02

,.001

,.001

1.00

1.57

2.97

17.86

.952.61

1.765.00

9.7732.66

.08

,.001

,.001

1.00

1.11

2.36

.671.85

1.284.35

.68

.006

1.00

1.38

3.05

.892.14

1.815.13

.15

,.001

ASA 5 American Society of Anesthesiologists; CI 5 confidence interval; MBP 5 mechanical bowel preparation.

Contant et al8 showed that MBP was associated with fewer

intra-abdominal abscesses after anastomotic leakage

compared with no MBP in elective colorectal surgery.

However, both studies show no difference in anastomotic

leakage rates. In summary, this leaves us with controversial

effects of MBP on anastomotic leakage and postoperative

infection rates. As a result the influence of applying or

withholding MBP on survival in patients surgically treated

for colorectal cancer remains unpredictable and unclear.

When looking at literature regarding MBP and longterm survival, Nicholson et al retrospectively collected data

of 1,730 patients who underwent potentially curative

colorectal cancer surgery.15 One thousand four hundred

sixty patients were treated with MBP and 270 patients

were not. Median follow-up was 3.5 (range .1 to 6.7) years.

They found a 28% survival benefit in favor of patients

treated with MBP (HR*** .72, .57 to .91) (P 5 .005).

controlled trials to their data and find no difference in anastomotic leakage rate between MBP and no MBP.2,8,10 Other

effects of MBP on postoperative complications have been

thoroughly investigated presenting controversial results.

Bucher et al11,12 suggest that MBP is associated with structural alteration and inflammatory changes in the large

bowel wall and that MBP is associated with higher postoperative morbidity rates in elective left-sided colorectal surgery. This is supported by Bretagnol et al, who noted that

MBP was associated with a significantly higher rate of infectious extra-abdominal complications.7 Mean hospital

stay was significantly longer for patients treated with

MBP in both studies.11,13 In contrast, authors of the French

Greccar III trial demonstrated that rectal cancer surgery

without MBP was associated with higher risk of overall

and infectious morbidity rates and suggest continuing to

perform MBP before elective rectal resection for cancer.14

Table 3

Complication rate after elective surgery for patients with colorectal cancer with and without preoperative MBP

Complication

MBP1 (n 5 177)

MBP2 (n 5 205)

No. of patients with complications*

Anastomotic leakage

Wound infection

Urinary tract infection

Pneumonia

Intra-abdominal abscess

Fascia dehiscence

59

7

18

12

14

6

2

82

8

25

18

16

9

6

MBP 5 mechanical bowel preparation.

*Patients can have more than one complication at a time.

(33%)

(4%)

(10%)

(7%)

(8%)

(3%)

(1%)

(40%)

(4%)

(12%)

(3%)

(8%)

(4%)

(3%)

110

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 210, No 1, July 2015

However, this survival advantage was no longer significant

after adjustment for presentation for surgery (HR .85, .67 to

1.10) (P 5 .220). This can be clearly explained because of

the fact that patients undergoing emergency surgery are

usually not treated with MBP and that the emergency

setting is associated with poorer outcome.16,17 The authors

of this study conclude that neither postoperative complications nor long-term survival are improved by MBP in regards to colonic cancer. However, this retrospective

cohort study has several limitations. Their main conclusion

was based on all-cause mortality and not on cancer-related

mortality. In addition, patients were not randomized between MBP and no MBP and the decision for applying

MBP was solely made ad hoc by the medical staff before

surgery, creating a potential source of bias.

The results of the underlying study show that MBP has

no influence on all-cause and cancer-related long-term

survival in patients surgically treated for colorectal cancer

with a median follow-up of 6.7 years. Adverse events

relating to colorectal cancer survival would be expected

within this time frame. These findings were expected as we

found no difference in anastomotic leakage and other

postoperative morbidity rates between the MBP1 and

MBP2 groups in this study. One of the limitations of this

study is the selection procedure. We selected patients from

only 2 of the 13 hospitals who participated in a previous

randomized trial comparing the anastomotic leakage rate in

patients treated with and without MBP.8 By selecting patients only surgically treated for cancer, we created an

imbalance between MBP1 and MBP2 (177 vs 205,

respectively) and a possible selection bias cannot be

excluded. An additional limitation is that in 17 patients

the cause of death could not be recollected. For these 17 patients, cancer-related mortality was both calculated when

deaths were presumed cancer related and when left out.

There were no differences between both calculations.

Data are only shown when deaths were presumed cancer

related as this is most probable. As survival depends on

many factors, our study is underpowered. A large randomized trial would be preferable with long-term survival as

primary endpoint in a cancer-related patient group.

In conclusion, our results from a subgroup of a randomized trial suggest confirmation of our hypothesis that MBP

has no influence on long-term survival in patients surgically

treated for colorectal cancer. However, more research is

required to draw firm conclusions.

References

1. Fa-Si-Oen PR, Verwaest C, Buitenweg J, et al. Effect of mechanical

bowel preparation with polyethyleneglycol on bacterial contamination

and wound infection in patients undergoing elective open colon surgery. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005;11:15860.

2. Slim K, Vicaut E, Launay-Savary MV, et al. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on the role of mechanical bowel preparation before colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2009;

249:2039.

3. Guenaga KK, Matos D, Wille-Jrgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;

21:CD001544.

4. Pineda CE, Shelton AA, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. Mechanical

bowel preparation in intestinal surgery: a meta-analysis and review

of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:203744.

5. Walker KG, Bell SW, Rickard MJ, et al. Anastomotic leakage is predictive of diminished survival after potentially curative resection for

colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 2004;240:2559.

6. McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage

on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for

colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2005;92:11504.

7. Kube R, Mroczkowski P, Granowski D, et al. Anastomotic leakage after colon cancer surgery: a predictor of significant morbidity and hospital mortality, and diminished tumour-free survival. Eur J Surg Oncol

2010;36:1204.

8. Contant CM, Hop WC, vant Sant HP, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial.

Lancet 2007;370:21127.

9. Slim K, Vicaut E, Panis Y, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical

trials of colorectal surgery with or without mechanical bowel preparation. Br J Surg 2004;91:112530.

10. Jung B, Pahlman L, Nystrom PO, et al. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colonic resection.

Br J Surg 2007;94:68995.

11. Bucher P, Gervaz P, Soravia C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation before elective leftsided colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2005;92:40914.

12. Bucher P, Gervaz P, Egger JF, et al. Morphologic alterations associated

with mechanical bowel preparation before elective colorectal surgery:

a randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;49:10912.

13. Bretagnol F, Alves A, Ricci A, et al. Rectal cancer surgery without mechanical bowel preparation. Br J Surg 2007;94:126671.

14. Bretagnol F, Panis Y, Rullier E, et al. Rectal cancer surgery

with or without bowel preparation. The French Greccar III

multicenter single-blinded randomized trial. Ann Surg 2010;

252:8638.

15. Nicholson GA, Finlay IG, Diament RH, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation does not influence outcomes following colonic cancer resection. Br J Surg 2011;98:86671.

16. Cuffy M, Abir F, Audisio RA, et al. Colorectal cancer presenting as

surgical emergencies. Surg Oncol 2004;13:14957.

17. Porta M, Fernandez E, Belloc J, et al. Emergency admission for cancer: a matter of survival? Br J Cancer 1998;77:47784.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Rabies: Elimination of in BangladeshDocument41 paginiRabies: Elimination of in BangladeshFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Overview of New Death Certificate PDFDocument59 paginiOverview of New Death Certificate PDFFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Department SOP V4.1Document17 paginiEmergency Department SOP V4.1Faisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Emergency Department SOP V4.1Document17 paginiEmergency Department SOP V4.1Faisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- All About Rabies!: Level 3Document27 paginiAll About Rabies!: Level 3Faisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Patient's Follow Up Profile SU1Document2 paginiPatient's Follow Up Profile SU1Faisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Charter of Duties of Upazila Parishad Officers PDFDocument28 paginiCharter of Duties of Upazila Parishad Officers PDFFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Epidemic Situation of Tuberculosis in Bangladesh PDFDocument2 paginiEpidemic Situation of Tuberculosis in Bangladesh PDFFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Landscape Photography With Your Smartphone: PhotzyDocument30 paginiLandscape Photography With Your Smartphone: PhotzyFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Prescribed Leave Rules, 1959 (Bangla)Document3 paginiThe Prescribed Leave Rules, 1959 (Bangla)Faisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Epidemic Situation of Tuberculosis in Bangladesh PDFDocument2 paginiEpidemic Situation of Tuberculosis in Bangladesh PDFFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Malaria Treatment Guidelines-2 ND Edition 2011Document210 paginiMalaria Treatment Guidelines-2 ND Edition 2011Kevins KhaembaÎncă nu există evaluări

- WHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Document160 paginiWHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Jason MirasolÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- BSMMU MS UROLOGY CurriculumDocument16 paginiBSMMU MS UROLOGY CurriculumFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Kdigo-Gn-Guideline GN PDFDocument143 paginiKdigo-Gn-Guideline GN PDFFerry JuniansyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Snake Bite As A Public Health Problem Bangladesh PDocument7 paginiSnake Bite As A Public Health Problem Bangladesh PFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- CXR Reading in TB Suspects - JATADocument32 paginiCXR Reading in TB Suspects - JATAFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment GuidelinesDocument223 paginiTreatment Guidelines14568586794683% (6)

- National Guidelines and Operational Manual For Tuberculosis Control PDFDocument90 paginiNational Guidelines and Operational Manual For Tuberculosis Control PDFFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment of Liver AbscessDocument1 paginăTreatment of Liver AbscessFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- KDIGO AKI Guideline DownloadDocument141 paginiKDIGO AKI Guideline DownloadSandi AuliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- SAM Guideline PDFDocument95 paginiSAM Guideline PDFFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Asthma - Bronchiolitis - COPD GuidelinesDocument84 paginiNational Asthma - Bronchiolitis - COPD GuidelinesFaisol Kabir86% (7)

- Data CollctionDocument3 paginiData CollctionFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- National Nipah Virus Guideline BangladeshDocument77 paginiNational Nipah Virus Guideline BangladeshFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathology BinderDocument406 paginiPathology BinderFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatomy BinderDocument816 paginiAnatomy BinderFaisol Kabir100% (1)

- Networking - How To Transfer Files Between Ubuntu and Windows - Ask UbuntuDocument3 paginiNetworking - How To Transfer Files Between Ubuntu and Windows - Ask UbuntuFaisol KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Surgical Nursing Brunner 2016Document74 paginiSurgical Nursing Brunner 2016Faisol Kabir100% (1)

- Komposisi z350Document9 paginiKomposisi z350muchlis fauziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inhibidores de La ECADocument16 paginiInhibidores de La ECAFarmaFMÎncă nu există evaluări

- BibliopocDocument4 paginiBibliopocKarlo ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18Th June 2019 Plab 1 Mock Test Plab ResourcesDocument30 pagini18Th June 2019 Plab 1 Mock Test Plab Resourceskhashayar HajjafariÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCP Ineffective Airway Clearance Related To Lung Impairment PNEUMOTHORAXDocument5 paginiNCP Ineffective Airway Clearance Related To Lung Impairment PNEUMOTHORAXMa. Elaine Carla Tating0% (2)

- Training Workshop On Attitudinal ChangeDocument5 paginiTraining Workshop On Attitudinal ChangeSam ONiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homeopathy and PaediatricsDocument15 paginiHomeopathy and PaediatricsCristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FurosemideDocument5 paginiFurosemideRaja Mashood ElahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Msds Nano PolishDocument5 paginiMsds Nano PolishGan LordÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 11 Occlusal Adjustment PDFDocument8 paginiChapter 11 Occlusal Adjustment PDFDavid ColonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- List Alat OK Mayor Dan Minor 30 07 2022 20.12Document72 paginiList Alat OK Mayor Dan Minor 30 07 2022 20.12dehaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test 6 Question BankDocument43 paginiTest 6 Question Bankcannon butlerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Masseter HypertrophyDocument6 paginiMasseter Hypertrophysanchaita kohliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of 226Document35 paginiAssessment of 226ajay dalaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Template HalodocDocument104 paginiTemplate HalodocSonia WulandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Congenital HypothyroidismDocument36 paginiCongenital HypothyroidismRandi DwiyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cervical Cancer - PreventionDocument10 paginiCervical Cancer - PreventionRae Monteroso LabradorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neuromuscular Blocking DrugsDocument3 paginiNeuromuscular Blocking DrugsYogi drÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peran Perawat Dalam Penanggulangan Bencana: Vol 6, No 1 Mei, Pp. 63-70 P-ISSN 2549-4880, E-ISSN 2614-1310 WebsiteDocument8 paginiPeran Perawat Dalam Penanggulangan Bencana: Vol 6, No 1 Mei, Pp. 63-70 P-ISSN 2549-4880, E-ISSN 2614-1310 WebsiteEbato SanaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 70000769rev.2ecube7 EngDocument599 pagini70000769rev.2ecube7 Engrizkiatul brawijayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tracheostomy CareDocument7 paginiTracheostomy CareJoanna MayÎncă nu există evaluări

- QUESTIONNAIREDocument3 paginiQUESTIONNAIREKatherine Aplacador100% (4)

- Prenatal RhogamDocument3 paginiPrenatal Rhogamgshastri7Încă nu există evaluări

- Case Report Acute Otitis MediaDocument28 paginiCase Report Acute Otitis Mediamayo djitro100% (2)

- + +Sandra+Carter +TMJ+No+More+PDF+ (Ebook) PDFDocument49 pagini+ +Sandra+Carter +TMJ+No+More+PDF+ (Ebook) PDFMassimiliano Marchionne0% (1)

- Charkoli ProjectDocument2 paginiCharkoli ProjectckbbbsrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 3 Cot Filipino Pandiwa q4Document9 paginiGrade 3 Cot Filipino Pandiwa q4Maricar FaralaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Therapy For Autism Spectrum Disorders (Cto)Document21 paginiFamily Therapy For Autism Spectrum Disorders (Cto)Julie Rose AlboresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and Related PathologyDocument2 paginiAtlas of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and Related PathologyMaria PatituÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wellness Check PrintableDocument2 paginiWellness Check PrintablethubtendrolmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDe la EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDe la EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDe la EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe la EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (24)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDe la EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (42)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe la EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (80)