Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ibuprofen Caffeine Disadvantages

Încărcat de

divyenshah3Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ibuprofen Caffeine Disadvantages

Încărcat de

divyenshah3Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

5.

2 Combinations with Caffeine

79

the possibility of modifying or optimising pain control using dexibuprofen for

different acute and chronic painful states. The extended-release and microencapsulation systems may be useful for long-term therapy of rheumatic conditions, with

the benet of once or twice daily therapy coincident with less uctuation in

peaktrough plasma concentrations, and, therefore, less variation in pain responses.

An L-arginine complex with dexibuprofen has been found to be absorbed at a faster

rate than the acid alone (Fornasini et al. 1997) and so may have utility as a rapidly

acting analgesic for short-term use. The L-arginine may also have other actions

relating to its stimulation of nitric oxide production.

5.2

Combinations with Caffeine

The rationale for addition of caffeine to ibuprofen and other analgesics has been

based on the premise of raising the analgesic ceiling of the analgesic. The

addition of caffeine to NSAIDs and paracetamol has been investigated for over

three decades as an adjuvant to enhance pain relief (Aronoff and Evans 1982;

Sunshine and Olson 1989; Zhang 2011). Combinations of caffeine and sodium

salicylate and aspirin have been available in the UK since 1949, and have been

mentioned in several pharmacopoeias (Martindale The Extra Pharmacopoeia 1958;

Reynolds 1993). Caffeine is mentioned in the British National Formulary (2009) as

a weak stimulant to enhance analgesia, but the alerting effect, mild habit-forming

properties, and possible provocation of headache may not always be desirable.

Earlier studies of the efcacy due to the addition of caffeine were largely negative,

except the combination with paracetamol (Laska et al. 1983, 1984).

Ibuprofencaffeine combinations have been investigated by several workers for

efcacy compared with that of ibuprofen (Stewart and Lipton 1989; Dionne and

Cooper 1999). Combinations of ibuprofen with caffeine have been shown to be

more effective than ibuprofen alone in the dental pain model (Forbes et al. 1990,

1991; McQuay et al. 1996). In particular, enhanced pain relief has been observed

with doses of 100 mg caffeine and 200400 mg ibuprofen (Forbes et al. 1990, 1991;

McQuay et al. 1996; Dionne and Cooper 1999). Ibuprofen 400 mg with caffeine

200 mg has been found to give greater pain relief in the treatment of migraine than

ibuprofen 400 mg alone (Stewart and Lipton 1989). Caffeine has also been found to

enhance the pain relief with ibuprofen in tension headache (Diamond et al. 2000;

Sparano 2001) and in childrens headache (Dooley et al. 2007).

There are, however, several issues that are raised about the use of combinations

of caffeine with ibuprofen, as well as with other non-narcotic analgesics/nonsteroidal anti-inammatory drugs (NSAIDs) which include:

(a) The pharmacological rationale for including caffeine; what is the pharmacological basis or mechanism for the enhanced analgesic activity?

(b) The confounding effects from the intake of caffeine-containing beverages,

estimated to be of the order of 100400 mg daily (Rall 1990; Reynolds,

Martindale, The Extra Pharmacopoeia; Nawrot et al. 2003; Rainsford 2004a).

80

5 Drug Derivatives and Formulations

(c) The possibility of increased incidence of gastric adverse effects, especially in

the stomach from stimulation of gastric acid secretion leading to gastric distress

(Rainsford 2004a) or CNS toxicity (Thayer and Palm 1975; Christian and Brent

2001; Nawrot et al. 2003).

As a nervous system stimulant, caffeine acts by inhibiting phosphodiesterase,

a well-known property which leads to an increase in the second messenger

cyclic-30 ,50 -adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), as well as acting as an antagonist

of central adenosine receptors. Studies in laboratory animal models of analgesia

show that caffeine, like that of some selective adenosine antagonists produces

analgesic effects principally via central adenosine A1 receptors (Ahlijanian and

Takemori 1985; Poon and Sawynok 1998), and this is the generally accepted mode

of clinical analgesia (Dunwiddie and Masino 2001). Thus, from the viewpoint of

contribution to the action of caffeine in the combination with ibuprofen, the focus

would seem to be on the central actions as an A1 receptor agonist.

Cronstein and co-workers (1999) provided evidence from studies in mice, in

which the genes for inammatory cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) or transcription

factor, nuclear kappa B (NFB) proteins were selectively knocked out, that the

mode of acute anti-inammatory actions of aspirin or salicylic acid was due to the

anti-inammatory effects of adenosine acting on the NFB signal transduction

pathway. Using mice lacking the gene for the adenosine A2A-receptor, Cadieux

et al. (2005) have shown that their polymorphonuclear neutrophil leucocytes

(PMNs) have diminished capacity to induce expression of COX-2, but not that

in monocytes. This would suggest that adenosine receptor activation leads to

increased COX-2-derived prostaglandins (PGs) from PMNs, so producing an

increase in acute inammatory reactions. A2A-receptor agonists reduce expression

of adhesion molecules and a range of pro-inammatory mediators [e.g., reactive

oxygen species, tumour necrosis factor-a (TNFa)] (Sullivan 2003). It is also known

that adenosine A1-receptors mediate plasma exudation in a non-prostaglandin,

non-nitric oxide mediated fashion (Rubenstein et al. 2001). These effects are

different from the effects of caffeine mediating analgesia in the central nervous

system. However, as peripheral anti-inammatory effects of NSAIDs are central to

their analgesic actions (Rainsford 1999b, 2004c), it is possible that caffeine

contributes to analgesic effects of NSAIDs or paracetamol indirectly via activation

of adenosine A2 receptors in both the peripheral and central nervous systems.

As far as adverse reactions are concerned, it appears that in the randomised

controlled trials in acute pain models there are no appreciable adverse reactions

from the ibuprofencaffeine combination compared with that of ibuprofen alone

(McQuay et al. 1996). Some mild CNS effects have been reported, ranging from

excitatory reactions and irritability; this may be especially evident in individuals

who are genetically predisposed to these reactions (Ellinwood and Lee 1996).

A condition known as caffeinism, which is a acute and chronic effect from

intake of 500600 mg caffeine per day (equal to approximately 79 cups of tea or

47 cups of coffee), is probably a health risk (Ellinwood and Lee 1996). Caffeine

preparations in analgesics have 5065 mg caffeine (Zhang 2001). At these doses

5.3 IbuprofenCodeine Combinations

81

taken 46 times daily, the amount of caffeine taken would be within the intake of

caffeine-containing beverages.

The common adverse events attributed to caffeine are: (1) associations with

increased myocardial infarction, tachycardia, and increased blood pressure, (2)

insomnia, anxiety, tremor, tenseness, and irritability, (3) increased free fatty acids

and hyperglycaemia, (4) nausea, vomiting, and stimulation of gastric acid secretion,

(5) increased diuresis, and (6) urticaria (Ellinwood and Lee 1996), gastrooesophagal reux, symptoms of anxiety and tachycardia in infants and children

(Ellinwood and Lee 1996). With long-term intake of caffeine-containing

analgesics, addiction may develop coincident with the analgesic abuse syndrome

(Ellinwood and Lee 1996; Rainsford 2004c). There has been concern that drinking

>78 cups of coffee per day may be associated with an increased incidence of

stillbirths, pre-term deliveries, low birth weights of infants and spontaneous

abortions, but other factors including intake of analgesics per se may contribute

to these states (Beers and Berkow 1999). Concerns about the possibility of the risks

of mutagenicity, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity led to an assessment of these

risks by the US Food and Drug Administration and several reviews (Thayer

and Palm 1975). A variety of in-vitro and in-vivo experiments and studies had

been reported since 1948 from which both positive and negative observations

were recorded (Thayer and Palm 1975). A considerable number of animal studies

of genetic changes, enhancement of dominant lethal changes, and teratogenic

potential in rodents as well as in-vitro studies in cell lines, in relation to the

pharmacokinetics and tissue/organ distribution of caffeine, were analysed and

assessed by Thayer and Palm (1975) in their comprehensive review.

In conclusion, it appears that caffeine may have some moderate potentiating

effects on analgesia from NSAIDs or paracetamol, but where these combinations

are taken in large quantities for long periods of time there are risks of CNS adverse

reactions, and at extremes analgesic abuse syndrome. Considering the availability

of other combinations with ibuprofen (e.g., paracetamol, codeine) which are

probably more effective than the ibuprofencaffeine combination, it would not

seem of appreciable therapeutic benet to use ibuprofencaffeine mixtures. It

would appear just as simple and more pleasurable to take ibuprofen alone with

coffee, tea or other caffeine-containing beverages.

5.3

IbuprofenCodeine Combinations

The combination of codeine with aspirin or paracetamol has been a popular and

effective analgesic in moderate to severe pain for over 3040 years (Reynolds 1993;

Martindale; Cooper 1984). Combination of ibuprofen with codeine has been found

to be more efcacious than either the drug alone, placebo or other NSAIDs in pain

following episiotomy or gynaecological surgery (Norman et al. 1985; Cater et al.

1985; Sunshine et al. 1987), tonsillectomy (Pickering et al. 2002), post-operative

dental pain (Mitchell et al. 1985; Giles et al. 1986; McQuay et al. 1989, 1992,

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Pka, Log P, Log D and AbsorptionDocument31 paginiPka, Log P, Log D and Absorptiondivyenshah3Încă nu există evaluări

- Postanesthetic Aldrete Recovery Score: Original Criteria Modified Criteria Point ValueDocument3 paginiPostanesthetic Aldrete Recovery Score: Original Criteria Modified Criteria Point ValueBonny ChristianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ludwig's AnginaDocument22 paginiLudwig's AnginaDevavrat SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan On Pituitary Gland (Endocrine SystemDocument37 paginiLesson Plan On Pituitary Gland (Endocrine SystemRosalyn Angcay Quintinita100% (1)

- PURPLE ROUTE Normal TimetableDocument3 paginiPURPLE ROUTE Normal Timetabledivyenshah3Încă nu există evaluări

- Open Systems Pharmacology SuiteDocument597 paginiOpen Systems Pharmacology Suitedivyenshah3Încă nu există evaluări

- Nitrofurantoin 50 and 100 MF UKPARDocument30 paginiNitrofurantoin 50 and 100 MF UKPARdivyenshah3Încă nu există evaluări

- Dose Linearity and Dose ProportionalityDocument39 paginiDose Linearity and Dose Proportionalitydivyenshah3100% (3)

- IV Profile TheoriticalDocument10 paginiIV Profile Theoriticaldivyenshah3Încă nu există evaluări

- In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation: Importance of Dissolution in IVIVCDocument5 paginiIn Vitro-In Vivo Correlation: Importance of Dissolution in IVIVCdivyenshah3Încă nu există evaluări

- B Lood: Bleeding and Thrombosis in The Myeloproliferative DisordersDocument13 paginiB Lood: Bleeding and Thrombosis in The Myeloproliferative DisordersJicko Street HooligansÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Council of Indian Medicine New Delhi: Syllabus of Ayurvedacharya (Bams) CourseDocument22 paginiCentral Council of Indian Medicine New Delhi: Syllabus of Ayurvedacharya (Bams) CourseAnanya MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal MigrainDocument6 paginiJurnal MigrainReksyÎncă nu există evaluări

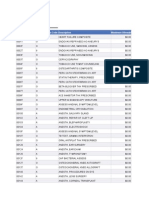

- 2009 Fee ScheduleDocument1.123 pagini2009 Fee ScheduleNicole HillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction of CKDDocument7 paginiIntroduction of CKDAndrelyn Balangui LumingisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scheduling: IndiaDocument5 paginiScheduling: IndiaCristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collagen FoodsDocument11 paginiCollagen FoodsPaul SavvyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Article Yoda THD DM (Manuskrip)Document4 paginiReview Article Yoda THD DM (Manuskrip)shafiyyah putri maulanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Information MSQ KROK 2 Medicine 2007 2021 PEDIATRICSDocument112 paginiInformation MSQ KROK 2 Medicine 2007 2021 PEDIATRICSReshma Shaji PnsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ob WARDDocument7 paginiOb WARDNursingNooBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science 8 Quarter 4 Shortened Module 2 CELL DIVISION Week 2Document6 paginiScience 8 Quarter 4 Shortened Module 2 CELL DIVISION Week 2Alvin OliverosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Center in Gastroenterology and HepatologyDocument12 paginiResearch Center in Gastroenterology and Hepatologynihilx27374Încă nu există evaluări

- The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India: Part - Ii (Formulations) Volume - I First Edition Monographs Ebook V.1.0Document187 paginiThe Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India: Part - Ii (Formulations) Volume - I First Edition Monographs Ebook V.1.0VinitSharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dalay Panishment of FormalinDocument4 paginiDalay Panishment of Formalinmutiara defiskaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classification of Drugs Are: Hepatoprotective Drugs E.g.: Silymarin Antibiotics E.G.Document2 paginiClassification of Drugs Are: Hepatoprotective Drugs E.g.: Silymarin Antibiotics E.G.Navya Sara SanthoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Committee Opinion: Preparing For Clinical Emergencies in Obstetrics and GynecologyDocument3 paginiCommittee Opinion: Preparing For Clinical Emergencies in Obstetrics and GynecologyMochammad Rizal AttamimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Package Insert - 048437-01 - en - 422243Document22 paginiPackage Insert - 048437-01 - en - 422243HadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of MenengitesDocument8 paginiManagement of Menengiteskhaled alsulaimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Does The Behaviour of Using Electronic Cigarette Correlates With Respiratory Disease Symptoms?Document6 paginiDoes The Behaviour of Using Electronic Cigarette Correlates With Respiratory Disease Symptoms?Ninuk KurniawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monobind Assay Technical GuideDocument16 paginiMonobind Assay Technical GuideDaNny XaVierÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3rd Ccpbiosimconference Abstract BookletDocument82 pagini3rd Ccpbiosimconference Abstract BookletRajeev Ranjan RoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eastfeeding StuartMacadamDocument80 paginiEastfeeding StuartMacadamDiana Fernanda Espinosa SerranoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBC Reviewer Anaphy LabDocument9 paginiCBC Reviewer Anaphy LabARVINE JUSTINE CORPUZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surgical Drains and TubesDocument3 paginiSurgical Drains and TubesYusra ShaukatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Graves DiseaseDocument13 paginiGraves DiseaseGerald John PazÎncă nu există evaluări

- CASE STUDY PPT Group1 - Revised WithoutvideoDocument34 paginiCASE STUDY PPT Group1 - Revised WithoutvideoSamantha BolanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apothio Hemp LawsuitDocument58 paginiApothio Hemp LawsuitLaw&CrimeÎncă nu există evaluări