Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Theory & Psychology: Developmental Continuum Vygotsky Through Wittgenstein: A New Perspective On Vygotsky's

Încărcat de

Maribel CalderonTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Theory & Psychology: Developmental Continuum Vygotsky Through Wittgenstein: A New Perspective On Vygotsky's

Încărcat de

Maribel CalderonDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Theory & Psychology

http://tap.sagepub.com/

Vygotsky through Wittgenstein : A New Perspective on Vygotsky's

Developmental Continuum

Domenic F. Berducci

Theory Psychology 2004 14: 329

DOI: 10.1177/0959354304043639

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://tap.sagepub.com/content/14/3/329

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Theory & Psychology can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://tap.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://tap.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://tap.sagepub.com/content/14/3/329.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Jun 1, 2004

What is This?

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

Vygotsky Through Wittgenstein

A New Perspective on Vygotskys Developmental

Continuum

Domenic F. Berducci

Toyama Prefectural University

Abstract. In this paper, I focus on aspects of Vygotsky and Wittgenstein

that relate to training and learning. Following the order of Vygotskys

developmental continuum, I demonstrate that the ideas of the two thinkers

virtually agree when their work deals with early forms of training that

precede operating on that continuum. However, when that initial training

develops into mature social interaction, the rules pertaining to Vygotskys

developmental continuum apply to the interaction at hand. I argue and

demonstrate that from that time on Vygotskys views and Wittgensteins

views become irreconcilable.

Key Words: conceptual confusions, developmental continuum, learning,

training, Vygotsky, Wittgenstein

I divide this paper into five sections (excluding the Discussion). In the first,

Background section, to orient the reader, I delineate relevant background

information about both Vygotsky and Wittgenstein. Next, in the Philoso-

phy section, I demonstrate how Vygotskys theory is modeled after portions

of Spinozas philosophy, and then relate that discussion to Wittgenstein.

Following, in the Earliest Training section, I outline Vygotskys and

Wittgensteins ideas on the earliest form of training, and show that they

strongly agree in that both declare this type of training to be necessarily

behavioristic. In the next section, Rules, I introduce Wittgensteins concept

of rules and relate it to its relationship with Vygotskian thought. In the

Conversing section, I demonstrate that Vygotskian and Wittgensteinian

ways of thinking diverge. Here, Vygotskian theory appears to constitute a

slight improvement over Cartesianism. However, I conclude that Wittgen-

steinian thought proves both Descartes and Vygotsky to be conceptually

confused.

To accomplish my goal of reexamining Vygotskys ideas concerning

training and his developmental continuum via Wittgenstein, I decided to

adhere, as much as possible, to original sources, especially Vygotsky (1987).

Theory & Psychology Copyright 2004 Sage Publications. Vol. 14(3): 329353

DOI: 10.1177/0959354304043639 www.sagepublications.com

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

330 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

In particular, I focused on his explication and use of the developmental

continuum, and any work of Wittgensteins, or comments on Wittgenstein

and Vygotsky, that are directly related to my goal. Thus, my current

undertaking constrained me to infrequently, if at all, refer to some seminal

and seemingly related works (e.g. Lawrence & Valsiner, 2003; Van der Veer

& Valsiner, 1991, 1994).

Background

Vygotsky

During Vygotskys time, two schools of psychology dominated

mechanistic and idealist psychologiesand, according to him, the method-

ology of each contained fundamental errors. Vygotsky applied a corrective,

not by combining these two schools, but rather by neutralizing them via

creating a Marxist-compatible psychology under the direct influence of

Marxist writings, Spinozan philosophy and various literary figures.

More specifically, late 19th-century Russian academics divided the study

of humankind into two sections following traditional Cartesian divisions:

one side was devoted to the natural scientific study of the body, the other to

the philosophical/psychological study of the mind/soul (Cole & Maltzman,

1969, p. 4).

Contemporaneously, the works of three scholars, Darwin, Fechner, and

Sechenev, influenced the reconciliation of the above split. Though not

psychologists, their findings hinted at a Spinozan (monistic) outlook and

thus provided a model for Russian and, later, Soviet psychology by uniting

two heretofore separate worlds in each of their respective fields. Darwins

evolutionary theory demonstrated a plausible continuity between humans

and animals; Fechners study discovered a relationship between physical

events and psychic responses; and Sechenevs psychophysiological work

linked the natural scientific study of humans with the philosophical study of

animals (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 2).

In the early 1920s, after the Revolution, Soviets, though influenced by the

work of those scholars mentioned above, continued to be torn between

existent ideological traditions in psychology; between that ideology which

totally ignored consciousness (mechanistic psychology), and that which

totally ignored behavior (idealist psychology) (Vygotsky, 1978, pp. 45).

This indecision was marked by the larger debate between the mechanists

and the idealist dialecticians; the latter dominated Soviet philosophy for

several years in the form of Deborins school of Hegelian Marxism (Daniels,

1996, p. 205). The Soviets leaned toward the mechanists, yet continued to

debate what conception of materialism would be best suited for Marxism.

Those advocating the mechanistic ideology did not want to completely deny

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 331

idealist Hegelian dialectics; they did not do so, but required any academic

study to constrain itself to what was observable by the methods of natural

science. They needed somehow to include thought and consciousness in the

observable. Spinoza appeared to be the answer.

In relation to Spinozan thought, both the mechanists and Hegelian

dialecticians held different opinions. The former dismissed Spinoza as a

metaphysician, while the dialecticians held him to be both a materialist and

a dialectician. They settled the dispute politically. At a meeting of the

Second All-Union Conference of Marxist-Leninist Scientific Institutions,

attendees condemned mechanistic ideas as undermining dialectical materi-

alism (Proyect, 2002). This victory for the dialecticians was short-lived,

however, and again a political solution was needed and found in Stalin. He

concluded that dialecticians advanced the idealism of Hegel too far. The

newly ordained view constituted a compromise between the mechanists and

the dialecticians, and was ultimately decided by Stalins codifying dialec-

tical materialism.

Vygotsky, active at this time, was able to take advantage of this

uncertainty by aiming to synthesize contending views of psychology. He

achieved this through applying the unifying force of Spinozas monistic

philosophy. Vygotsky ultimately created a comprehensive approach that

both describes and explains the relation of thought to action, and the

development of higher psychological functions from lower. Following the

tenets of Spinozan materialist philosophy, his psychology stressed the social

origins of thinking.

Vygotskys psychology emerged as scientific, in line with Soviet im-

peratives, that is, it was objective, yet included the study of consciousness.

Spinozas attempt centuries earlier to bring human beings within the

framework of the natural sciences (Spinoza, 1677/2000, p. 50) was coming

to be realized via Vygotskys work. Spinozan monism, in tandem with the

official Soviet policy of dialectical materialism, allowed Vygotsky to study

all, physical as well as mental, phenomena as processes in change and

motion, processes on which his work is predicated (Valsiner, 1988,

p. 328).

Spinoza was a materialist; his ideas agreed with materialism and ulti-

mately assisted it to evolve into its highest form (Saifulin & Dixon, 1984).

For the Soviets, the objective, scientific study of thought was possible

because of Spinozan ideas. He posited thought to be an attribute of, not

separate from, nature. Spinoza argued that thought was a product of matter

rather than vice versa. This idea placed him above any representation of

mechanistic materialism for Engels (1968), who applied this Spinozan

argument in his Dialectics of Nature. There, Engels argued that it is in the

nature of matter (lower) to evolve into thinking (higher) beings. Addition-

ally, it is this relation of thought to matter that distinguishes dialectical

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

332 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

materialism from crude mechanical materialism. Marxs teleological view

evidences that he also understood Spinoza in this way.

A profoundly scientific outlook constitutes the base of dialectical materi-

alism. Hegels idealist influence was of course basic, but, according to the

Soviets, without a materialist approach to society, it would have been

impossible to explain the laws of human cognition (Saifulin & Dixon,

1984).

For the Soviets, dialectical materialism comprised a philosophical synthe-

sis of the phenomena of human society, cognition, nature and the revolu-

tionary transformation of the world.

The core concept of Vygotskys work is transformation. Transformation

may be pictured as a continuous revolutionary and evolutionary line of

human development stretching to infinity. Vygotskys complete devel-

opmental continuum comprises four stages: phylogenetic (transformation

from ape to human), sociohistorical (primitive to modern), ontogenetic

(child to adult) and microgenetic (less to more capable individual). Between

each pair of stages, a qualitative jump is evident. I must note here that in the

following analysis of development and transformation, I will concentrate on

the final stage, microgenetic, though the analysis applies to the entire

continuum.

Vygotskys microgenetic continuum is comprised of six components:

Written Speech (WS), External Speech (ES), Private Speech (PS), Inner

Speech (IS), Thought (Th.), and Motivation (Mo.).

Since most readers are somewhat familiar with these components, I will

here only explicate their basic meanings as revealed in the latest translation

of Vygotskys original work Thought and Word (1987). Written Speech

consists of virtually any form of written communication: essays, letters,

dissertations, and so on. This form of speech (though written, Vygotsky

considers it speech) is monologic and constitutes the most mature and least

abbreviated and predicated component of Vygotskys developmental con-

tinuum. Through Written Speech, writers must make meaning explicit,

since, when writing, no interlocutors are co-present to negotiate, confirm or

clarify meaning. Next in line follows External Speech, the form Vygotsky

dubs as the source of all of the continuums components. ES consists of all

forms of social interaction: lectures, conversations, arguments, and so on. It

constitutes a more abbreviated and predicated speech form than WS since in

the former an interlocutor is necessarily co-present to negotiate, and so on.

The form subsequent to ES on the continuum, Private Speech, renamed from

Egocentric Speech to prevent confusion with Piagets concept, holds many

meanings (Diaz & Berk, 1992), but for our purposes it is speech to self, used

to control the self, while attempting to perform a task alone. PS originates in

ES as the voice of a teacher, caretaker, parent, and so on, during some type

of training. This speech form is more abbreviated than either WS or ES; a

speaker using PS usually drops the subject of an utterance, since, according

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 333

to Vygotsky, a speaker knows it is the self who is speaking. In place of

uttering to self, for instance, I should turn right while making a decision,

the abbreviated turn right would suffice. Though the form of these two

utterances differs, meaning remains equivalent. PS comprises both an

internal and external form. Inner Speech follows. It is comprised of spoken

thought and is more abbreviated and predicated than any of the preceding

forms. Abbreviation and predication both increase as we move down the

continuum towards the final components, Thought and Motivation. Thought

is said to be more abbreviated than IS, while to Motivation, the final

component, Vygotsky assigns the most abbreviated of all the speech forms

on the continuum.

In addition to conceiving the developmental continuum as being com-

posed of six components as listed here, we may also view it as being divided

into two larger groups of forms, inner and outer components. The outer

components consist of the Written and External Speech forms, and the

audible portions of Private Speech, while the remaining components form

the inner: Inner Speech, Thought and Motivation.

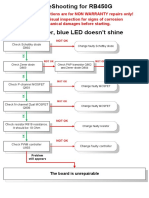

Figure 1 depicts a complete version of the microgenetic developmental

continuum, with components listed in proper relation. It is essential to keep

in mind while reading the subsequent discussion that meaning is conserved

along this continuum, while its vehicle, speech, appearing in any of the

forms of the continuum, is transformed.

Wittgenstein

Wittgenstein has been classified an anti-philosopher since he was, at

minimum, opposed to theory building (Grayling, 1988/1996; Hacker,

1993/1998), the defining activity of most philosophers. He opposes univer-

salistic philosophical and psychological explanations and concepts on logi-

cal, not empirical, grounds. It is in this sense that we would find his

wide-ranging opposition to the impetus behind large portions of Vygotskian

theory.

Wittgenstein was not a psychologist, and neither would, nor could,

contribute directly to Vygotskian psychology by either empirically support-

ing or disputing Vygotskys claims. Wittgenstein performed no empirical

research to test or refute his own or others claims; rather, simply stated, his

later work consisted of a logical or grammatical method used to examine

language use to reveal conceptual errors. Though Wittgensteins method

does not and cannot offer empirical solutions to any particular field, it

dissolves conceptual confusions; it can therefore offer clarity to any field.

WS ES PS IS Th. Mo.

Figure 1. Developmental continuum

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

334 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

As a final point in this very brief exposition of Wittgensteins relevant

background, I would like to offer the following quote to readers. I find it to

be one of the most powerful and comprehensive explications of Wittgen-

steins later work; it fends off superficial criticism, and offers a compre-

hensive feel and justification for his method:

[Wittgensteins grammatical/conceptual method] seems to trivialize our

inquiry; we want to investigate the essence of thinking and Wittgenstein

tells us to examine the use of words. Surely words are arbitrary; and that

this word is used thus, that one thus is arbitrary too. Yet the nature of

thinking is anything but arbitrary! The [above] objection rests on in-

comprehension. It is grammar that determines the essence of something (cf.

Exg. para. 371f.). The rules for the use of the word think constitute what

is to be called thinking, and that is the essence or nature of thinking. Of

course, words are arbitrary; what is called thinking could have been

called something else. The use of the sign thinking could have been

different; but if it had been different, it would not have the meaning it has,

and so it would not have signified thinking. Investigating the grammar of

the word thinking and seeking to lay bare the essential nature of thought

are one and the same endeavor (cf. PI para 370). (Hacker, 1993/1998,

p. 147)

Philosophy

In this next section, I would like to expose Vygotskys philosophical

orientation, creating a foundation from which to appreciate the remaining

sections of this paper. Being aware of Vygotskys philosophical background

aids in understanding his notions of inner and outer. In addition, this

awareness helps one realize that portions of both his psychology and

Wittgensteins work are opposed in a way that is different, subtler than, and

yet related to, the way that Wittgensteins work opposes Cartesian thought.

At the outset, it is necessary to point out that Vygotsky was a monist,

which means that we must exercise special caution when discussing his

particular version of inner and outer. Because of his adherence to monist

tenets, these notions do not form two distinct entities, as in the received

wisdom of Descartes. Therefore, Wittgensteinian critiques of Cartesian-

psychologistic studies, though readily available, cannot directly apply.

In the following section I will detail portions of Spinozan philosophy

directly relevant to Vygotskian theory. Through that detailing, I will reveal

how Vygotsky used Spinozan monism to advance a distinctive picture of his

psychology.

Through Spinoza, Vygotsky sought an alternative to Cartesian dualism,

which . . . established for centuries to come the conflict between materialistic

scientific psychology and idealistic, philosophical psychology (Kozulin,

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 335

1986, p. xiv). From this impetus, Vygotsky originated his desire to dissolve

both behavioristic and idealistic psychologies.

Three fundamental concepts support Spinozas philosophy: Substance,

Attributes and Modes.

Scholars classify Spinoza as a substantial monist, meaning that every

existent thing forms part of one indivisible Substance, and that Substance is

God. Ironically, Spinoza originated this definition of Substance via Descartes

definition as that which requires nothing but itself in order to exist (Kenny,

1998, p. 221). Descartes not only counted God, but, as is familiar to most of

us, also mind and matter as distinct substances.1 This distinction creates

well-known, seemingly intractable questions, such as How can mind and

matter interact?, How does the mind cause the body to act?, and so on.

These questions, rather than difficult, are conceptually confused, according

to Wittgenstein.

Spinoza applied portions of the ontological argument to argue the proof of

existence of his one Substance. At the outset, he claims that it is necessary

for the one Substance to bring itself into existence because if any other entity

were necessary, then that one Substance could not fit the definition of

substance (Kenny, 1998, p. 221). Spinozan Substance equals a unified whole

containing within itself an explanation of itself. Though unified, Substance

consists of an infinite number of Attributes, though we can only comprehend

two of them, thought and extension. Thought constitutes the inner or mental

Substance, ideas and such, while extension constitutes the outer or material

Substance, objects, and so on.2

The next concept in Spinozas triumvirate is Attributes. Spinoza

(1677/2000) defined an Attribute as that which intellect perceives of

Substance, as constituting its essence (p. 17). By this definition, he means

that the relation between Substance and Attributes does not equal the

relation between separate entities. This is true first because Substance and

Attributes belong to logically different categories, and next because Attrib-

utes certainly do not equal entities. Simply stated, Spinoza means that the

one Substance can only be understood through its Attributes (p. 18).

Spinoza claimed that the two Attributes, mind and body, are inseparable

because, according to him, all ideas of a body and other extended things

constitute a mind, and, complementarily, a mind exists only insofar as a

body exists (Kenny, 1998). Mind and body in Spinozas system thus

mutually constitute each other.

The final concept in Spinozas tripartite system, Modes, exists as different

types of things within the one Substance. Spinoza (1677/2000) defines a

Mode as that which is in something else, through which it is conceived (p.

19). Each and every existent thing constitutes a Mode of the one Substance:

paintbrushes, bicycles, soymilk, and so on. Further, the variety and number

of these Modes extend to infinity.

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

336 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

Additionally, in Spinozas monism, the tenet that mind is produced by the

development and subsequent transformation of matter is, as we will see,

consistent with the putative operation of Vygotskys developmental con-

tinuum. Further, directly related to an essential influence of Vygotskian

psychology, monism is viewed as being typical of dialectical materialism

(Saifulin & Dixon, 1984). In relation to this claim I must reiterate that

Spinoza and, of course, Marx were materialists. Therefore we may conclude

that the thinking of Marx, Spinoza and their student Vygotsky forms a

consistent and comprehensive theoretical package.

A demonstration follows that reveals an analogical relation that obtains

between Spinozas three concepts, Substance, Attributes and Modes, and

Vygotskys: developmental continuum, inner and outer distinctions, and the

components of his developmental continuum, respectively.

First, as stated, Vygotskys developmental continuum is analogous to

Spinozas Substance in that his continuum, as Spinozas Substance, is an all-

inclusive entity. The developmental continuum explains the origin of itself

through transformation of each one of its components into an adjacent

component, for example ES transforms into PS, and so on. This conception

can be expressed differently. Every component of Vygotskys developmen-

tal continuum generates, and is generated from, another component in that

same continuum. Just as Spinozas one Substance can transform itself into

existence, so does Vygotskys developmental continuum. Each component

of Vygotskys continuum originates in External Speech, and each of the

subsequently created components feeds back onto, transforms from and

develops into the remaining components.

Next, Spinozan Attributes, thought and extension, are directly analogous

to Vygotskys inner and outer. The conceptions inner and outer equal the

ways we conceive Vygotskys Substance, the developmental continuum, just

as thought and extension are ways we perceive Spinozas Substance.

Vygotskys Attributes, inner and outer, do just that, attribute meaning to the

developmental continuum, and aid in uniting that same continuum.

That Vygotskys continuum can be considered equivalent to Spinozas

Substance can also be inferred from terminology used in the application of

Vygotskian theory. Please examine, for example, the oft-used expressions

intermental and intramental. The grammar of these expressions indicates that

only mental components comprise the continuum. However, though true,

this indication does not follow for all of Vygotskys ideas concerning the

developmental continuum all of the time. Please recall that both inner and

outer attributes constitute the continuum in the following sense: Every

component exists as inner in that an individuals actions originate in, and are

transformed from, the inner. For example, social actions are transformed

from Motivation, Thoughts, Inner Speech, and so on. On the other hand,

every component simultaneously exists as outer, in that those Motivations,

Thoughts, and so on, were originally transformed from outer experience, that

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 337

is, transformed from ES. In the Vygotskian system, outer was previously

inner, and vice versa. Technically, in either Vygotskys or Spinozas system,

if everything is claimed to be mental, or if everything is claimed to be

material, both are true because these claims function merely as intellectual

designations, that is, as Attributes. Vygotsky and Spinoza do not claim to

posit an essential distinction between inner and outer, as does Descartes.

Rather, thought and extension, inner and outer, and similar expressions,

form a continuum and constitute transformations of one and the same

substance. These Attributes, inner and outer, simply comprise a heuristic

whereby humans can perceive Vygotskys Substance, the developmental

continuum.

Thus because in Spinoza and Vygotskys systems inner and outer are not

discrete entities, they are not as obvious targets as the Cartesian system for

Wittgensteins method, but they constitute targets nonetheless.

Finally, the arrival at the Vygotskian analogue for Spinozas modes is at

hand. Until this point I have continually used the phrase components of

Vygotskys developmental continuum. Each of these componentsWS,

ES, PS, IS, Th. and Mo.comprises an analogy to a Spinozan mode. To

help us understand this analogy, let us refer back to Spinozas obtuse

definition of Modes, that which is in something else, through which it is

conceived (Spinoza, 1677/2000, p. 19). The Vygotskian Modes exist within

the developmental continuum, and it is through these Modes that the

developmental continuum is constituted and conceived.

Now armed with Vygotskys philosophical orientation and its relation to

Wittgenstein, we can make sense of the next three sections: Earliest

Training, Rules and Conversing.

Earliest Training

In this section I will examine both Vygotsky and Wittgensteins thoughts on

the initial stages of any type of training. We will see, regarding these earliest

training forms involving either an infant or an absolute novice, that their

ideas strongly concur.

Vygotsky

For Vygotsky, a caretaker and an infant involved in the earliest training are

not yet working on his developmental continuum, but work together

inadvertently, via this training, in an attempt to move onto that continuum.

To accomplish this type of training, and to subsequently move onto the

Vygotskian continuum, Vygotsky notes that human infants possess a priori

biological abilities allowing them to at least physically discriminate among

objects in their environment, and to respond to a caretakers signals. These

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

338 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

native abilities comprise the minimum necessary to initiate early training,

and, as we will see, this training is necessarily behavioral because of those

infants complete lack of linguistic and social skills. For an infant to know

that a caretaker is naming an object, for example, that infant would need to

possess an a priori ability to command some part of the caretakers language

(Grayling, 1988/1996, p. 73). Because this type of infant ability is logically,

as well as empirically, impossible, the pair must begin with behavioristic

training. Therefore behavioristic training, training that can proceed success-

fully without the necessity of an infant possessing the caretakers language

of instruction, solves the putative bootstrapping problem.

Further, in this earliest training, Vygtosky claims that human infants are

analogous to non-human animals, specifically apes, in that both infants and

apes can understand only context-specific stimuli. In this earliest training, a

caretakers words and gestures are context-specific and context-bound, and

serve merely to indicate. The indicative function of a caretakers actions

equals a purely referential signal, and is thus devoid of mature meaning

(Goudge, 1965, p. 65). A caretakers use of referential signals denotes a

stimulusresponse type of interaction. For this type of training to ensue,

nothing more than signals is either necessary or possible.

As training ensues, participants through social interaction come to under-

stand meaning in the training, and, if successful, initiate intersubjectivity,

resulting in an infant coming to understand, rather than react to, a care-

takers words and gestures. The infants understanding demonstrates that the

caretaker/infant pair has now moved out of the earliest stages of training and

onto Vygotskys developmental continuum, and thus can be said to be

participating in External Speech. Wertschs (1985) truck-puzzle experiments

constitute a lucid example of participants movement to External Speech. In

those experiments mothers were told to instruct their children to refer to a

completed truck-puzzle, to guide their completing a disassembled version of

1

that same puzzle. One mother and her 2 2-year-old child initially were not

able to communicate because this mother began by using a non-signal type

word, wheel, to refer to the wheel, while the child continued to perceive

those wheels as crackers. The childs perception indicated that he was

working in his intrasubjective world: a world preceding understanding, a

world preceding entry onto Vygotskys developmental continuum. Finally,

after several attempts at communication, the mother resorted to using a

signal-like form, a deictic, for example this, allowing the mother and child to

continue the training, and thus to continue moving towards working on the

developmental continuum.

According to Vygotsky, if any training continues successfully, with a

normal child, the participants necessarily would advance along the devel-

opmental continuum to a point where the child can ultimately operate

autonomously. If this truck-puzzle interaction had continued until its suc-

cessful conclusion, the child would have internalized the mothers inter-

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 339

action through transforming her External Speech, first into interaction with

self, Private Speech, and on to further components of the continuum.

Vygotskys theory explains learning just this way, by the transformation of

interaction into succeeding internal planes.

Wittgenstein

Wittgensteins conception of the earliest stages of training is strongly

consistent with, and yields further insight into, Vygotskys ideas on infant

training. In relation to his type of training, Wittgensteins comments concern

not only infants, but also any absolute novice trained in any domain. Even

though this is the case, the relation between Vygotskys ideas on training

infants, or Wittgensteins ideas on training absolute novices, remains the

same.

Wittgenstein, as Vygotsky, believes that the generation of meaning

through social interaction must occur in the earliest stages of training. For

Wittgenstein, since an infant possesses no cognitive skills at this time, the

caretaker serves as a proxy for its cognition. Training a novice how-to-do in

this way comprises an act of understanding only on the part of the caretaker;

the novice will later display understanding, if that training succeeds.

For Wittgenstein, as we saw for Vygotskys training at this earliest stage,

a human infants abilities equate to a non-human animals. Wittgenstein

offers a bee rather than an ape as an example (Williams, 1999, p. 195). Also

for Wittgenstein, infants possess an innate biological (non-cognitive) ability

to discriminate among objects. Thus, an absolute novice needs merely to

possess abilities suggested by behaviorists. For this type of training to ensue,

it is unnecessary for this type of novice to obey social rules. Novices here

need no special a priori cognitive ability; neither need any be posited on

their behalf. A novices ability to discriminate facilitates what Wittgenstein

calls ostensive training, requiring only the use of signals for its accomplish-

ment, because ostensive training is anchored in stimulusresponse inter-

action. Ostensive training does not require an absolute novice to possess

cognitive, semantic or epistemic competency to explain its ability to

successfully participate. Wittgensteins alternative [to a priori cognitive

ability] is that the child is trainable in a socially structured environment in

which the ability or competence to be taught is already mastered by the

teacher (Williams, 1999, p. 196). For Wittgenstein, an absolute novice

requires fewer abilities than those to be acquired in training.

Wittgensteins argument concerning training an absolute novice is in a

sense analogous to Augustines claims concerning language learning.

Augustine describes the learning of human language as if the child came

into a strange country and did not understand the language of the country

(Wittgenstein, 1958, 32). For Wittgenstein an absolute novice needs

neither to have nor to understand a caretakers language. Rather it is through

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

340 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

the social interaction that constitutes training that a novice comes to think

and understand language. Vygotskian theory agrees.

In Wittgensteinian ostensive training, as in Vygotskys earliest training,

the wordobject relation is conditioned. Both of these types of training

constitute a causal process bringing about the association between an object

and a word, resulting in a novices ability to parrot, rather than to

understand. The parroting novice in a sense acts, but does so without

intention; he or she merely reacts, consistent with the fact that an absolute

novices abilities resemble a non-human animals. However, the ability to

parrot constitutes a necessary prerequisite to eventually advance to under-

standing, possibly later in the training.

Rules

At this point, advancing the discussion necessitates bringing in Wittgen-

steins complex thinking regarding rules. First we must be aware that

Wittgensteinian rules guide rather than coerce. Also, these rules do not

constitute a calculus that individuals must follow. Further, these rules do not

pre-exist a practice; they are what a practice makes of them, and are

expressed through that practice.

For Wittgenstein, rules form a significant and complex aspect of training.

For him, absolute novices first conform to a caretakers rules, and then

subsequently come to obey those same rules (Williams, 1999). Novices

involved in the earliest levels of training do not, because they cannot, obey

rules. These novices must first engage in ostensive/behavioristic training

where they mimic rule-obeying, and act, but without intention. The possibil-

ity of Action without intention exists (Rubinstein, 1981, p. 111), and it is

this type of acting that constitutes rule-conforming. It is training that

changes unintentional actions to intentional, and thus true rule-obeying,

actions. A novices acquiring an understanding of rules requires assimilation

into social practices through training (Williams, 1999, p. 203). As alluded to

above, a caretakers goal for the training, expressed through his or her

actions, serves as a novices vicarious intention, and re-creates rules for the

novice (Grayling, 1988/1996, pp. 8081).

As mentioned, an infant or an absolute novice, as a participant in

behavioristic interaction, merely conforms to rules; by the end of the training

an infant or novice obeys them. Conforming to rules in early training

seemingly concurs with Vygotskys ideas concerning earliest training.

However, for him, infants do not come to obey public rules, rather they (or

any learners) come to obey their own internal rules later in training; they

follow their own self-control through applying the internal modes of

Vygotskys continuum: PSISTh.Mo. In short, they obey the self-control

that originated with the caretakers public other-control. For Vygotsky, the

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 341

novice has internalized the interaction and obeys the caretaker through

obeying itself. Rules, if I can apply the concept in relation to Vygotskian

thought, become a component of the novices consciousness through train-

ing.

For Wittgenstein, obeying a rule is a public endeavor, and thus can be

seen directly. The relationship of Vygotsky and Wittgenstein in this arena

can easily be seen when we consider that for Wittgenstein (1958) following

a rule is analogous to obeying an order ( 206). For Vygotsky, following

orders is the essence of his training: one initially follows an order of an

other, and eventually an order of the self.

For both Vygotsky and Wittgenstein, the ability to obey rules increases as

novices come to act for themselves. As implied by the discussion until this

point, Vygotskys system explains ordering oneself, or coming-to-act-for-

oneself as a gradual transformation of and between the inner modes of his

continuum: PS, IS, Th. and Mo. On the other hand, a Wittgensteinian may

claim that the novice and caretaker, instead of transforming their interaction,

are moving from one language game to another; for example moving from

an earlier game, behavioristic training, to a later one, mature interaction.

However, Wittgenstein does not explain how movement from one language

game to another occurs. Because he is neither a developmental psychologist

nor involved in empirical analyses, he does not possess the means to

describe how this change can come about. However, for Wittgenstein, an

infant by the end of training embodies the rule of that training, and is thus

becoming a functioning and therefore understanding member of society.

This successful training results in a continuation of a system of belief, whose

certainty comes from the fact of belonging to a community.

Let us now analyze a single example of the initial stages of a training

session. In this instance we will see that training fosters Wittgensteinian

intention, or, in Vygotskian terms, volition. Specifically, we will see here a

caretaker inadvertently guiding an infant to becoming an agent. Obeying, as

opposed to conforming to, a rule may be viewed as agency, volition or

individualization. Please examine the following example adapted from

Vygotsky (Wertsch, 1985, p. 64):

infant: ((moves hand towards bottle, index finger extended))

caretaker: you want the bottle?

((picks up bottle and gives it to infant))

In the above example, for Vygotsky, the infants moving its hand with

extended index finger towards a baby bottle does not constitute pointing. It

must be emphasized that this is so, even though the infant displays the

correct form, that is, the extension of the index finger. Rather, the infants

hand movement constitutes a hunger reaction, a transformation of the

infants hunger into external behavior. Reacting, since it is not volitional,

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

342 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

thus does not constitute any way in which a mature norm-using member of

society points.

In Wittgensteinian terms, the infant reaching for the bottle is analogous to

someone accidentally making a correct move in chess. This type of move

cannot comprise a move unless someone who knows chess rules performs

that action. Thus, following the same logic, the infant above is not pointing

to the bottle. Additionally, that infant has no intention to point, simply

because it is not possible for it to have intention at this time in its

development. However, the infant ultimately becomes intentional, becomes

volitional by virtue of the caretakers perceiving the hand-movement as

pointing. The caretaker perceiving it so, structures the situation by imputing

meaning to the infants moving its hand toward the bottle, which can be

viewed as the caretaker extending a courtesy (Williams, 1999, p. 204) to

the infant, which is necessary for the infant to eventually become an

intentional, volitional agent (Edwards, 1997, p. 308). The caretakers pre-

supposing that the infant is performing a mature pointing action also

structures the training in which the novice comes to, in Wittgensteinian

terms, obey a rule. Through continually following that rule, in a particular

context, in that language game, the infant becomes a more mature member

of society, and also ultimately becomes another potential caretaker. This

outcome is similar for Vygotsky. In his system, however, the infant

internalizes the interaction, and in that way becomes a mature member.

In both Vygotsky and Wittgensteins systems, to become an agent one

must be treated as if one can do something of ones own volition, as in the

above infantbottle example. One must be treated as if one can decide.

Initially, the infant reaching towards the bottle constitutes a reaction, a

transformation of hunger for Vygotsky, or an expression of hunger for

Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein (1980) explains that the purpose of any training is to

straighten you up on the track if your coach is crooked on the rails. Driving

it afterwards is something we shall leave to you ( 39e).

Training creates agents and places them on rails. Rails or tracks comprise

a metaphor for a rule: a track that the caretaker has been following during

training, and a track that the novice will eventually follow autonomously.

Please note that the track metaphor represents the right way of doing things,

the way of the caretaker, the rule, the norm, the way to become a mature,

fully functioning member of society. It does not mean that a rule cannot be

broken or interpreted in any way by a listener. If a rule is broken or

misinterpreted in training, the action will be corrected, and it is this being-

corrected and subsequently acting-correctly that is analogous to interacting

on rails.

However, two discrete possibilities exist: one either interacts on the track

or off. No explanation from the Wittgensteinian literature exists as to how

one is initially put onto this developmental track. That is, no explanation

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 343

exists of how one moves to the next training interaction in the devel-

opmental line. One just finds oneself in that next training, in the next

language game. Vygotskys work with the developmental continuum, on the

other hand, demonstrates how interaction with more capable others trans-

forms infants into beings interacting on rails, following rules: that is,

Vygotskys work demonstrates how infants move onto his developmental

continuum.

Thus, interacting either on or off Wittgensteins track may each be viewed

as a discrete language game, consistent with his ahistorical, synchronic

method. Vygotskys method in this aspect is diametrically opposed. It is

historical and diachronic, and can and does demonstrate how development

ensues. Vygotskian theory allows for an historical link to bridge language

games. This opposition will be discussed below.

Table 1 summarizes the synoptic view of Vygotskian and Wittgensteinian

features of early training as presented in this section.

Conversing

It has been argued that substantial agreement obtains between Vygotskian

and Wittgensteinian ways of thinking concerning one type of language

game, initial training. In this section I will analyze interaction between more

mature members of society operating both on a Wittgensteinian track and on

the Vygotskian developmental continuum. In analyzing this type of inter-

action, insoluble differences between Vygotsky and Wittgenstein begin to

emerge.

Please recall that according to Wittgenstein, mature members of society

understand, intend and obey rules. Former novices, now mature, have

completed different types of training in the rules of language and society,

and are thus able to converse autonomously.

TABLE 1. Summary of Vygotskys and Wittgensteins ideas on

early training

Beginning of training Ending of training

Non-human human Mature member of society

Parroting Understanding

Rule-conforming Rule-obeying

Non-intentional Intentional

Non-volitional Volitional

Signal-using Symbol-using

Dependent Autonomous

Off track On track

Off developmental continuum On developmental continuum

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

344 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

According to Vygotsky, on the other hand, mature members of society

autonomously operate on his developmental continuum, because their pre-

vious training has been transformed into internal structures: Inner Speech,

Thought, and so on. At the appropriate time, for example while conversing,

these putative internal structures re-transform into external structures, in a

word, conversation.

In light of the previous agreements of Vygotsky and Wittgenstein in

relation to the earliest type of training, let us now examine a fragment from

Vygotskys original work, where interactants have completed training, and

converse as mature members of society.

In the following analysis, Vygotskys literary influences can be easily

seen (adapted from Vygotsky, 1987, p. 282).

Conversation Hidden Motivations

Sophia: Oh Chatskii, ((wants to hide her confusion))

I am glad to see you.

Chatskii: Youre glad, thats good. ((wants to appeal to her conscience

Though, can one who becomes through mockery))

glad in this way be sincere? ((wants to elicit openness))

For Vygotsky, mental forces always lie transformed, hidden, behind dis-

course. This conception follows Dostoevsky, Stanislavsky and other literary

figures who teach that behind each of a characters lines there stands a

desire that is directed toward the realization of a definite volitional task

(Vygotsky, 1987, p. 282).

The above conversation fragment, including Vygotskys analysis of

participants motivations, demonstrates two modes from his developmental

continuum: External Speech, as the conversation between Sophia and

Chatskii; and their Hidden Motivations, as Vygotskys analysis of that same

conversation.

According to Vygotskian theory, Sophia and Chatskiis motivations

constitute the ultimate transformation, the final internal plane of the devel-

opmental continuum. Succumbing to the logic of Vygotskys theory, Sophia

and Chatskiis internal motivations precede, and subsequently transform into

(note, do not cause), their utterances. That is, the interlocutors motivations

are ultimately transformed into Thought, then into Inner Speech, culminat-

ing in Sophia and Chatskiis actual utterances, External Speech. It is

important to note that the meaning of these utterances resides ultimately in

that final plane, Motivation, rather than residing in the actual utterances.

The first question one may ask about Vygotskys ascription of motivations

in the above fragment is How does he or anyone arrive at those motiva-

tions? According to Vygotsky, he does not infer them from the interlocu-

tors actions, as would a Cartesian. Rather, he claims that he can observe

Sophia and Chatskiis motivations directly. His claim is consistent with his

theory, because, for example, Private Speech forms a process internal in

nature but external in manifestationis accessible to direct observation and

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 345

experimentation (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 258). Thus, because internal processes

transform into external processes, his claim is therefore warranted that

interlocutors can have direct access to their partners internal processes.

The meaning of direct here carries special import in this discussion, thus

it is necessary to spend some time divesting its meaning in both Vygotskys

and Wittgensteins works. I will argue that Vygotskys and Wittgensteins

definitions of direct differ.

According to Vygotsky, when anyone hears anyone else speaking, they

hear a transformation of that speakers motivations; they hear a transformed

version of what was once located within that speakers mind. What they hear

comprises part of one and the same Substance, only transformed into a

different vehicle. Though access is through transformed material, Vygotsky

maintains that access to the inner is direct. If the argument of his transforma-

tional system is logically extended, then he must also mean that one can

directly observe an ape by observing a human, directly observe a primitive

by observing a modern, directly observe a child by observing an adult, and

so on. This way of construing the meaning of direct is confused.

Vygotskys concept of directness, though confused, may be viewed as

more direct than a Cartesians, in that in Vygotskys system, inference is

unnecessary to access anothers inner world; rather, a transformed version

avails itself. However, the act of inferring implies a gap, implies a Cartesian

absolute distinction between inner and outer, between thought and speech,

and so on, requiring two discrete entities, making direct access, in any sense

of the term, logically impossible.

A Cartesian analyzing the interaction between Sophia and Chatskii would

need to infer or guess the participants motivations or meanings. Cartesian

analysis necessitates inference because of the absolute distinction between

action (body) and private motivations (mind) that lies at the base of the

Cartesian system, logically excluding any type of direct access to a listener.

Therefore, according to Descartes, it is impossible to perceive an others

mind or experience directly. We can, however, experience others bodies or

their behavior directly. Ones own mind can be directly perceived or directly

experienced only by the self. In relation to the above example, Sophias own

motivations, according to Cartesians, would be directly accessible only to

her. Further, for Descartes, motivations or any mental process would need to

be the cause of Sophia and Chatskiis actions, as software controls hardware.

This confused argument also applies to those more materialistic Cartesians

who substitute brain for mind. Thus, I could argue in this sense that

Vygotskys access to the inner is more direct than a Cartesians.

Continuing, lets now examine an important quote concerning Wittgen-

steinian thinking that will help clarify this hidden and direct discussion:

structuring [training] is never fully eliminated though it is rightfully

obscured from view in the behavior and judgments of those who have

mastered a practice (Williams, 1999, p. 213). The phrase obscured from

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

346 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

view comprises the Wittgensteinian alternative to Vygotskys concepts:

hidden, internalization and transformation. Structuring in the above quote

equals training or Vygotskys External Speech. For Vygotsky, that structur-

ing is transformed into the behavior and judgments of less experienced

members of society. It is transformed into the inner, yet a putatively directly

accessible inner. For Wittgenstein, on the other hand, training discloses itself

directly in action, for example in a gesture, a gaze and a tone of voice. In

addition, for Wittgenstein, training reveals itself in our judgments, not

personal opinions, of an action; we judge a gesture to be aggressive, we

judge a gaze to be flirtatious, a tone of voice to be impudent, and so on.

Thus, for Wittgenstein, the contact between Sophia or Chatskiis minds,

or their understanding of each other, is direct and immediate in a sense

different than Vygotskys. Interlocutors such as Sophia and Chatskii cer-

tainly go beyond what people do and say, but not through inferring objects

or processes in the others mind, nor by observing a transformation of the

others mind. Rather, they, and we, can go beyond because we see

motivations on others faces, we hear motivations in the tone of others

voices, and so on.

The interlocutors motivations are, for Wittgenstein, what we, as mature

members of a particular society, know with certainty (Wittgenstein, 1969).

Some people are transparent to us; we can easily read them. We operate in

interaction based on that certainty. In the SophiaChatskii case we know

why they are doing what they are doing. This argument is analogous to

Wittgensteins well-known and oft-analyzed comments on pain (Grayling,

1988/1996; Hacker, 1993/1998; Wittgenstein, 1958). A natural expression of

the inner, for example pain or motivation, is revealed in outward criteria. In

the case of pain, an outward criterion may be the verbal expression ouch, or

a scream or some such. In the case of motivation, the outward expression

would be less obvious, but would show itself nonetheless in the behavior

. . . of those who have mastered a practice.

A complete analysis of Sophia and Chatskiis conversation is of course

not available in Vygotskys original work. However, we can be certain that

a certain look from Sophia, a particular movement of Chatskiis eye, a

special tone of Sophias voice, and so on, all of the micro-actions we were

trained to recognize as expressions of particular motivations, would reveal

themselves in that conversation. We were trained in recognizing and judging

these micro-actions relating to motivation just as we were trained to

recognize expressions of pain. Otherwise how would Vygotsky or anyone be

able to perceive the above motivations to the interlocutors behavior? The

answer from Wittgenstein is simple and direct. Sophia and Chatskii per-

ceived the motivations in each others actions. Now one may ask, What

about pretence? or What about the possibility of controlling ones pain, or

concealing ones motivations? Certainly pretence on the part of an actor is

possible, for example feigning or concealing a particular motivation or a

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 347

pain. But the ability to pretend or conceal does not disprove the fact that we

see motivations directly. The possibility of pretence or concealment only

demonstrates that the criteria for motivations, or other putatively inner

processes, are defeasible, and this defeasibility depends on the circum-

stances. That is, pretence may be functional in a different language game. In

this context we could ask Would there be a reason why someone would try

to pretend he or she was motivated in a certain way? An answer might be

for instance that a person may want to express to an employer his or her

desire to complete a certain job in order to get promoted, and so on. Or

another relevant question may be Why would someone try to control his or

her pain? A possible answer to this question may be that in a different

language game, one may want to control ones pain to prevent drawing

attention to oneself, for example during an important meeting. Because these

concepts controlling motivation or controlling pain exist, these language

games exist, are known directly without inference, and thus can be recog-

nized and utilized by mature members of society.

Inference as posited by a Cartesian as a procedure to contingently know

an others motivation is just nonsense, because inferring is logically un-

necessary to know that motivation; transformation of inner to outer as a

pathway to knowledge of other minds, as posited by Vygotsky is also

logically unnecessary. Vygotsky inherited the pictures of transformation,

and inner and outer, from Spinoza, and applied those pictures to create his

psychology. He did so rather than follow Wittgensteins dictum dont think,

but look! (Wittgenstein, 1958, 66). Vygotsky thought, applied the

received wisdom, and created unnecessary confusion. In Wittgensteinian

terms, Vygotsky, and Descartes as well, would be said to be conceptually

confused. Both Descartes and Vygotskys ways of conceptualizing inner

and outer are the result of their respective versions of conceptual confu-

sion.

Sophia and Chatskiis motivations, instead of being hidden in either

Cartesian or Vygotskian terms, are, as I have argued, for Wittgenstein,

explicitly open. Those motivations Vygotsky assigned to Sophia and Chat-

skii simply answer the question What are they doing? The answer

constitutes members knowledge of their language game. Therefore in

Sophia and Chatskiis conversation, we, as members of that community, and

because we have become members of that community, understand what

they are doing in that game because our understanding is based on social

competence (Ryle, 1949). Through that conversation Sophia directly demon-

strates her desire to hide her confusion, Chatskii directly demonstrates his

appeal to Sophias conscience, and so on.

Vygotskys suggested motivations from the above conversation can be

reformed into Wittgensteinian doings via Table 2. Through reformulating

these motivations, that is, reformulating Vygotskys wants to, into hiding,

appealing and eliciting, in short by reformulating Vygotskys wants to into

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

348 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

TABLE 2. Vygotskian motivations and Wittgensteinian doings

Vygotskian Motivations Wittgensteinian Doings

Wants to hide her confusion Hiding her confusion

Wants to appeal to her conscience Appealing to Sophias conscience

through mockery through mockery

Wants to elicit openness Eliciting openness

actions visible to an other, Vygotskys most secret internal plane of verbal

thinking [motivation] (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 283) is thus directly exposed and

demystified. Logically extending this argument, the entire developmental

continuum can be demystified.

The last section regarding initial training ended with a statement that

Wittgensteins method is ahistorical and synchronic, while Vygotskys is

historical and diachronic. In the vernacular, the components of Vygotskys

developmental continuum can be described thus: Written Speech is writing,

External Speech is speaking, Private Speech is talking aloud to oneself,

Inner Speech is talking silently to oneself, and so on. For Wittgenstein, each

of these Vygotskian modes can comprise a discrete language game, but their

descriptions cannot be decontextualized as I have presented here. For

example, External Speech must be about something, must be part of a

language game. A possible game is speaking angrily at a professor, or

speaking intently to an eager student; Private Speech can be trying to

decide something for oneself as one speaks aloud to oneself; Inner Speech

functions the same as Private Speech yet silent. Gestures and facial

expressions may accompany any of Vygotskys components. The relation to

Vygotskys concepts of Thought and Motivation is similar. One can act

thoughtfully or act with Motivation, with or without speech. None of these

modes comprising Vygotskys developmental continuum need to be viewed

as transformed entities, but they may be seen as public actions.

Discussion

In this analysis, I have shown that political and intellectual influences

created a welcoming atmosphere and thus aided Vygotsky in his attempt to

neutralize two existent schools of psychology, the internal idealist school

and the external mechanistic school. These forces were instrumental in

creating/forming Vygotskian theory and thus in initiating his overall goal of

creating a new psychological theory that satisfied both him and the Soviets.

Further, I have also shown that Vygotsky applied various and different pre-

existing pictures from monism and literature. He attempted to accomplish

this neutralizing through creating the developmental continuum, essentially

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 349

an extension of monistic thinking, which allowed inner and outer to be

united in one Substance, and formed a consistent and logically integrated

picture of these constructs as being transformations of each other. In

Vygotskian theory, the developmental continuum operated as a tool for

transforming his different modes, External Speech, and so on, while main-

taining one Substance, the developmental continuum itself, and thus avoid-

ing the confusion of Cartesian dualism. However, though successful in his

avoiding confusion, largely through applying Spinozan concepts to create

his theory, he failed to solve it, thus creating other confusions.

Vygotskys developmental continuum certainly is elegant, logically con-

sistent, avoids dualism, satisfies our lust for generality, and so on; however,

as we have begun to see, this construct is not, and cannot serve as, an

adequate or exact theory with which to analyze learning-interaction, because

it is based on various confusions.

As mentioned, the raison detre of Wittgensteins later work functioned to

neutralize or dissolve philosophical problems. Wittgensteins neutralization

of philosophical problems was more successful than Vygotsky s neutral-

ization of psychological problems in the sense that the result of Wittgen-

steins dissolution was absolute, largely because he based his type of

dissolution on conceptual rather than empirical analyses. Wittgensteins

philosophy served as a palliative, dissolving errors in thinking, but did not

fabricate an additional explanatory system, as did Vygotskys psychology.

Vygotskys use of monism and Marxism, instead of neutralizing mechanistic

and idealistic psychologies, created a parallel psychology. In other words, he

created a new, additional type of psychology, while Wittgenstein obliterated

traditional philosophical thinking.

I stated that Cartesian thought constituted a relatively easy target for

Wittgensteinian philosophy, largely because in Cartesian thought two dis-

crete and incommensurable entities exist, inner and outer. Though relatively

unproblematic to attack philosophically, Cartesianism lies insidiously em-

bedded in our everyday way of thought. The Wittgensteinian problem then

became one of making us aware of the confusions inherent in our everyday

and analytical thought processes, rather than fabricating a new philosophical

system to replace Cartesianism.

As opposed to Cartesianism, in Vygotskys monistic psychology, inner

and outer do not and cannot constitute discrete entities, since they form a

continuum. A borderline between Vygotskys inner and outer Attributes

does not exist. In addition, monistic thought is not as deeply embedded in

our practices as is Cartesian dualism. Thus, a lighter Wittgensteinian attack

should be able to remove any existent confusions in this area.

I find it difficult yet essential to remember that Vygotsky and Wittgenstein

differ fundamentally in their methodologies: Wittgensteins method is con-

ceptual, while Vygotskys is empirical. As we have seen, for Wittgenstein,

grammar determines the essence of anything. To paraphrase Hacker, our use

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

350 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

or concept of the word think in its different forms and multifarious contexts

determines what is thinking. For Vygotsky, on the other hand, thinking is an

empirical object, a singular unified socio-psychological process. For him,

thinking in the following utterances shares the same essence: I was thinking

about going to a movie and I was thinking intently to solve that math

problem. Following Spinozas thought, thinking in any context for Vy-

gotsky constitutes a transformation of an empirical object, that is, thinking

constitutes a transformation of External Speech. Monistic and Marxist

thinking influenced Vygotsky to discover this transformation; then he

justified his discovery, via experimentation, inference and possibly an

analogy from his own case.

For Wittgenstein, however, the word thinking can differ for each language

game it serves; and, further, for him, speaking and thinking can form two

distinct language games. For example, one can now either speak or think, or

one can speak thoughtfully, and so on. For Vygotsky, however, speaking in

any context necessitates thinking, since they comprise transformations of

each other.

As I also have established, Vygotsky and Wittgenstein do not always

disagree. In terms of the initial stages of any type of training, we did see a

strong concurrence between Vygotskian and Wittgensteinian thought. Both

agreed that initial training with an infant requires behavioristic or ostensive

training. Here both can agree, at least when discussing initial training,

because this level of training takes place before Vygotsky needs to invoke

his theoretical construct, the developmental continuum. One possible addi-

tional reason for their agreement here is that Vygotsky based his analysis of

the initial stages of training on observation. Following the Wittgensteinian

dictum dont think, but look!, he based this part of his analysis on looking

rather than thinking.

In the initial stages of training, for both Vygotsky and Wittgenstein,

infants possess the ability to respond to signals as non-human animals. Only

later in their development, in mature forms of interaction, do infants become

human and thus act autonomously, act as agents and as individuals, act with

intention and with volition. To sum up, in mature forms of interaction,

infants come to act, rather than react, as they do in initial stages of

training.

It is when analyzing mature interaction and applying Vygotskys devel-

opmental continuum and transformation (more thinking than looking) that

Vygotsky and Wittgenstein begin to differ. We saw this with their differing

meanings of the term direct. For Vygotsky, direct means that interlocutors

need not infer what is occurring inside of their partners heads. Rather, he

did this inferring for them. He originally inferred the existence of the inner

modes, Private Speech, Inner Speech, Thought and Motivation, in at least

two ways. First, he noticed that when children spoke to themselves while

completing a task, this Private Speech became abbreviated and predicated

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 351

relative to the External Speech that took place earlier with a caretaker. Next,

he observed that the amount of Private Speech decreased as these children

matured (Vygotsky, 1987, pp. 255262). From Private Speech, Vygotsky

then inferred its connection with Inner Speech. More specifically, he inferred

that since speech developing from ES to PS is abbreviated, the further we

move along the developmental continuum, the more abbreviated and predi-

cated speech must become. Thus, Inner Speech must be more abbreviated

than Private Speech; Thought must be more abbreviated than Inner Speech;

and, finally, Motivation must be more abbreviated than Thought. This

inferred, and thus putative, internalization for Vygotsky indicates trans-

formation.

My analysis has shown that using Wittgenstein, Vygotskian transforma-

tion need not be posited. As evidence of this non-need, as I presented earlier,

we can see our interlocutors motivations directly in action; one acts with

motivation; ones actions express ones motivation, and are a part of it. One

can observe a conversation partners actions and be certain of what is

happening in that interaction. It is this certainty that forms the ultimate basis

for knowing what is happening within an other. In sum, this certainty forms

the ultimate basis for meaning (Wittgenstein, 1969).

Following the implications of my initial analysis, I conclude that it is

incumbent upon present-day researchers to demonstrate how, without a need

to adhere to a theory and without applying psychologistic meta-concepts

such as transformation, developmental continuum, and so on, individuals in

interaction move from one language game to another. In short, I conclude

that it is possible, and less confusing, to demonstrate learning without

resorting to any type of traditional learning theory.

Finally, this paper has seemingly constituted an initial excursion into the

relationship of Vygotskian and Wittgensteinian ways of thought. However,

it is in a sense late in coming. Toulmin (1969) hinted at the relationship of

Vygotsky and Wittgenstein 35 years ago. In a note in his paper he wrote:

Vygotskys discussion of the relation between thought and inner speech

finds a close parallel in Wittgensteins remarks on the same topic in Zettel,

paras. 100ff. Some of Vygotskys aphorisms also have a strongly Wittgen-

steinian tone: e.g., A word is a microcosm of human consciousness, and

A thought may be compared to a cloud shedding a shower of words.

(p. 70)

Today we are armed with better translations, commentaries and applications

of Vygotskys work, as well as having available more complete translations

of Wittgensteins Nachlass. Lets get on with the task at hand!

Notes

1. For a fascinating (and brief) discussion of the contrast between Descartes and

Spinoza, please see Bennet (1965).

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

352 THEORY & PSYCHOLOGY 14(3)

2. I would like to diverge here slightly to present a quote from Wittgenstein

demonstrating his grammatical critique of monism:

353. But may it not be said: If there were only one substance, there

would be no use for the word substance? That however presumably

means: The concept substance presupposes the concept difference of

substance. (As that of the king in chess presupposes that of a move in

chess, or that of colour that of colours.) (Wittgenstein, 1967/1998,

p. 64)

Wittgensteins critique dissolves monism since there is no logical possibility to

discuss substance.

References

Bennet, J. (1965). A note on Descartes and Spinoza. Philosophical Review, 74(3),

379380.

Cole, M., & Maltzman, I. (Eds.). (1969). A handbook of contemporary Soviet

psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Daniels, H. (1996). An introduction to Vygotsky. London: Routledge.

Diaz, R.M., & Berk, L.E. (1992). Private speech: From social interaction to self-

regulation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Edwards, D. (1997). Discourse and cognition. London: Sage.

Engels, F. (1968). Dialectics of nature. In K. Marx, & F. Engels, Collected works

(pp. 338353). London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Goudge, T.A. (1965). Peirces index. Transactions of the C.S. Peirce Society 2

(Fall).

Grayling, A.C. (1996). Wittgenstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Original

work published 1988.)

Hacker, P.M.S. (1998). Wittgenstein: Meaning and mind: Vol. 3 of an analytical

commentary on the Philosophical investigations, Part I: Essays. Oxford: Black-

well. (Original work published 1993.)

Kenny, A. (1998). A brief history of western philosophy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kozulin, A. (1986). Vygotsky in context. In L.S. Vygotsky, Thought and language

(A. Kozulin, Ed.; pp. xilvi). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lawrence, J.A., & Valsiner, J. (2003). Making personal sense: An account of basic

internalization and externalization processes. Theory & Psychology, 13,

723752.

Proyect, L. (2002). Marxism mailing list archive. Monday, September 23, 2002,

8:38AM. Retrieved February 24, 2003. http://www.marxmail.org/.

Rubinstein, D. (1981). Marx and Wittgenstein: Social praxis and social explanation.

London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Saifulin, M., & Dixon, R.R. (Eds.). (1984). Dictionary of philosophy. New York:

International Publishers.

Spinoza, B. (2000). The ethics (G.H.R. Parkinson, Ed. and Trans.). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Toulmin, S. (1969). Ludwig Wittgenstein. Encounter, 32, 5871.

Valsiner, J. (1988). Developmental psychology in the Soviet Union. Brighton:

Harvester.

Downloaded from tap.sagepub.com at PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA on June 19, 2012

BERDUCCI: VYGOTSKY THROUGH WITTGENSTEIN 353

Van der Veer, R., & Valsiner, J. (1991). Understanding Vygotsky. Oxford: Black-

well.

Van der Veer, R., & Valsiner, J. (Eds.). (1994). The Vygotsky reader. Oxford:

Blackwell.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological

processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.).

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1987). Thought and word. In R.W. Riebe, &, A.S. Carton (Eds.),

The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky, Vol. 1: Problems of general psychology (pp.

243288). New York: Plenum.

Wertsch, J.V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Williams, M. (1999). Wittgenstein, mind and meaning: Toward a social conception

of mind. London: Routledge.

Wittgenstein, L. (1958). Philosophical investigations (G.E.M. Anscombe, Trans.).

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Wittgenstein, L. (1969). On certainty (G.E.M. Anscombe & G.H. von Wright,