Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

BP 22 - Notice of Dishonor

Încărcat de

Bam SantosDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

BP 22 - Notice of Dishonor

Încărcat de

Bam SantosDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

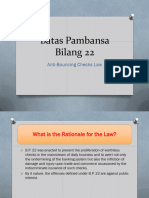

Batas Pambansa Blg.

22

Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 punishes any person who makes or

draws and issues any check to apply on account or for value, knowing

at the time of issue that he does not have sufficient funds in or credit

with the drawee bank for the payment of such check in full upon its

presentment, which check is subsequently dishonored by the drawee

bank for insufficiency of funds or credit or would have been dishonored

for the same reason had not the drawer, without any valid reason,

ordered the bank to stop payment. 1

The law as well provides the same penalty to upon any person

who, having sufficient funds in or credit with the drawee bank when he

makes or draws and issues a check, shall fail to keep sufficient funds or

to maintain a credit to cover the full amount of the check if presented

within a period of ninety (90) days from the date appearing thereon,

for which reason it is dishonored by the drawee bank.2

Elements of the offense

To be liable for violation of B.P. 22, the following essential

elements must be present:

(1) the making, drawing, and issuance of any check to apply for

account or for value;

(2) the knowledge of the maker, drawer, or issuer that at the

time of issue he does not have sufficient funds in or credit with

the drawee bank for the payment of the check in full upon its

presentment; and

(3) the subsequent dishonor of the check by the drawee bank for

insufficiency of funds or creditor dishonor for the same reason

had not the drawer, without any valid cause, ordered the bank to

stop payment.

Proving the knowledge of the maker

To hold a person liable under B.P. Blg. 22, the prosecution must

not only establish that a check was issued and that the same was

subsequently dishonored, it must further be shown that accused knew

1 Batas Pambansa Blg. 22, Section 1, Par. 1

2 Batas Pambansa Blg. 22, Section 1, Par. 2

at the time of the issuance of the check that he did not have sufficient

funds or credit with the drawee bank for the payment of such check in

full upon its presentment. This knowledge of insufficiency of funds or

credit at the time of the issuance of the check is the second element of

the offense.

Section 2 of B.P. Blg. 22 creates a prima facie presumption of

such knowledge. Said section reads:

SEC. 2. Evidence of knowledge of insufficient funds. The

making, drawing and issuance of a check payment of which is

refused by the drawee because of insufficient funds in or credit

with such bank, when presented within ninety (90) days from the

date of the check, shall be prima facie evidence of knowledge of

such insufficiency of funds or credit unless such maker or drawer

pays the holder thereof the amount due thereon, or makes

arrangements for payment in full by the drawee of such check

within five (5) banking days after receiving notice that such

check has not been paid by the drawee.

For this presumption to arise, the prosecution must prove the following:

(a) the check is presented within ninety (90) days from the date

of the check;

(b) the drawer or maker of the check receives notice that such

check has not been paid by the drawee; and

(c) the drawer or maker of the check fails to pay the holder of the

check the amount due thereon, or make arrangements for

payment in full within five (5) banking days after receiving notice

that such check has not been paid by the drawee.

In other words, the presumption is brought into existence only

after it is proved that the issuer had received a notice of dishonor and

that within five days from receipt thereof, he failed to pay the amount

of the check or to make arrangements for its payment. The

presumption or prima facie evidence as provided in this section cannot

arise, if such notice of nonpayment by the drawee bank is not sent to

the maker or drawer, or if there is no proof as to when such notice was

received by the drawer, since there would simply be no way of

reckoning the crucial 5-day period. A notice of dishonor received by the

maker or drawer of the check is thus indispensable before a conviction

can ensue. 3

3 Dico v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 141669, February 28, 2005.

Procedure in sending a notice of dishonor

In sending the notice of dishonor to the drawer, the rules on

service under the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure provide the modes of

service. Section 5, Rule 13, of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedures

states:

Sec. 5 Modes of service Service of pleadings, motions, notices,

orders, judgments and other papers shall be made either

personally or by mail.

In order to prove service of the notice, Section 13, of the same

rule provides the following requirements:

Section 13. Proof of Service. Proof of personal service shall

consist of a written admission of the party served, or the official

return of the server, or the affidavit of the party serving,

containing a full statement of the date, place and manner of

service. If the service is by ordinary mail, proof thereof shall

consist of an affidavit of the person mailing of facts showing

compliance with section 7 of this Rule. If service is made by

registered mail, proof shall be made by such affidavit and the

registry receipt issued by the mailing office. The registry return

card shall be filed immediately upon its receipt by the sender, or

in lieu thereof the unclaimed letter together with the certified or

sworn copy of the notice given by the postmaster to the

addressee.

Despite the criminal nature of B.P. Blg. 22 cases, jurisprudence

has previously affirmed these requirements to establish the fact of

service of the required Notice of Dishonor.

In King v. People4, the complainant sent the accused a demand

letter via registered mail. But the records showed that the accused did

not receive it. The postmaster likewise certified that the letter was

returned to sender. Yet despite the clear import of the postmasters

certification, the prosecution did not adduce proof that the accused

received the post office notice but unjustifiably refused to claim the

registered mail. The Court held that it was possible that the drawee

bank sent the accused a notice of dishonor, but the prosecution did

not present evidence that the bank did send it, or that the

accused actually received it. It was also possible that the

accused was trying to flee from the complainant by staying in

4 King v. People, 377 Phil. 692 (1999).

different addresses. But speculations and possibilities cannot take

the place of proof. The conviction must rest on proof beyond

reasonable doubt. (Emphasis and underline supplied.)

In Resterio v. People5. The court ruled that the mere

presentment of the two registry return receipts was not sufficient to

establish the fact that written notices of dishonor had been sent to or

served on the petitioner as the issuer of the check. Considering that

the sending of the written notices of dishonor had been done

by registered mail, the registry return receipts by themselves

were not proof of the service on the petitioner without being

accompanied by the authenticating affidavit of the person or

persons who had actually mailed the written notices of

dishonor, or without the testimony in court of the mailer or

mailers on the fact of mailing. The authentication by affidavit of the

mailer or mailers was necessary in order for the giving of the notices of

dishonor by registered mail to be regarded as clear proof of the giving

of the notices of dishonor to predicate the existence of the second

element of the offense. (Emphasis and underline supplied.)

In Ting v. CA6, it merely presented the demand letter and registry

return receipt as if mere presentation of the same was equivalent to

proof that some sort of mail matter was received by petitioners.

Receipts for registered letters and return receipts do not prove

themselves; they must be properly authenticated in order to serve as

proof of receipt of the letters. Likewise, for notice by mail, it must

appear that the same was served on the addressee or a duly

authorized agent of the addressee. In fact, the registry return receipt

itself provides that [a] registered article must not be delivered to

anyone but the addressee, or upon the addressees written order, in

which case the authorized agent must write the addressees name on

the proper space and then affix legibly his own signature below it. In

the case at bar, no effort was made to show that the demand letter

was received by petitioners or their agent. All that we have on record is

an illegible signature on the registry receipt as evidence that someone

received the letter. As to whether this signature is that of one of the

petitioners or of their authorized agent remains a mystery. From the

registry receipt alone, it is possible that petitioners or their authorized

agent did receive the demand letter.

5 G.R. No. 177438, September 24, 2012.

6 Ting v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 140665, November 13, 2000.

From these cases, the Supreme Court has ruled that in order to

prove the fact of sending a notice of dishonor, the prosecution must

not only present the actual notice of dishonor along with the registry

return, but must also provide as evidence the affidavit of the sender as

well as that of the person who actually mailed the letter. In addition, if

it has evidence of the fact that the drawer has consciously been

avoiding the receipt of the notice of dishonor, the prosecution must

present clear proof of such an act by the drawer.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Sample Engagement AgreementDocument3 paginiSample Engagement AgreementAugustine RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complaint-Affidavit - BP22Document4 paginiComplaint-Affidavit - BP22Eloisa SalitreroÎncă nu există evaluări

- INVESTIGATION DATA FORM - DOJ Revision 1Document1 paginăINVESTIGATION DATA FORM - DOJ Revision 1Jazz TraceyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appellees Memorandum Group 2Document9 paginiAppellees Memorandum Group 2Rudy G. Alvarez Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of KnowledfeDocument1 paginăAffidavit of Knowledfebhem silverioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comment To Motion PP Vs AjocDocument3 paginiComment To Motion PP Vs AjocDence Cris RondonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demand Letter Trust Receipt LawDocument1 paginăDemand Letter Trust Receipt LawERWINLAV2000Încă nu există evaluări

- Motion For ReinvestigationDocument3 paginiMotion For ReinvestigationVe NiceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notice of Change of Address - PP Vs Hao (Atty - Ching)Document2 paginiNotice of Change of Address - PP Vs Hao (Atty - Ching)Khorin FarneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crim. Case No. - : Normer Riden Bauden RingorDocument1 paginăCrim. Case No. - : Normer Riden Bauden Ringorblack stalkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of Service 2Document1 paginăAffidavit of Service 2Mark Rainer Yongis LozaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accion PublicianaDocument4 paginiAccion Publicianajodelle11Încă nu există evaluări

- 08 - Combined Verification, Certification Against Forum Shopping and Statement of Material DatesDocument2 pagini08 - Combined Verification, Certification Against Forum Shopping and Statement of Material Datesroy rebosuraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion For Satisfaction of JudgementDocument2 paginiMotion For Satisfaction of JudgementDennis0% (1)

- JA Collection of Sum of MoneyDocument5 paginiJA Collection of Sum of MoneyeileenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion For Special RaffleDocument4 paginiMotion For Special RafflepopstagemarketingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Partial Motion For ReconsiderationDocument3 paginiPartial Motion For ReconsiderationNinJj MacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notice of ClaimDocument4 paginiNotice of ClaimLou AragaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of Electronic FilingDocument1 paginăAffidavit of Electronic FilingMonica Gerero - BarquillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joint Affidavit of Desistance: Republic of The Philippines) Province of Nueva Vizcaya) S.S. Municipality of Bambang )Document2 paginiJoint Affidavit of Desistance: Republic of The Philippines) Province of Nueva Vizcaya) S.S. Municipality of Bambang )carlito alvarezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic of The Philippines Manila: Supreme CourtDocument8 paginiRepublic of The Philippines Manila: Supreme CourtPatrick Romano100% (1)

- (Complaint Affidavit For Filing of BP 22 Case) Complaint-AffidavitDocument2 pagini(Complaint Affidavit For Filing of BP 22 Case) Complaint-AffidavitRonnie JimenezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manifestation - Editha Santos (OTHER FORMS OF SWINDLING)Document2 paginiManifestation - Editha Santos (OTHER FORMS OF SWINDLING)Richard Conrad Foronda SalangoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ReplevinDocument4 paginiReplevinNicole SantoallaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reckless ImprudenceDocument5 paginiReckless ImprudencejeszamaeferrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Verification and Certification of Non-Forum ShoppingDocument1 paginăVerification and Certification of Non-Forum ShoppingjakeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hon. Marco Anacleto P. Buena: Preliminary Investigation, Administrative Adjudication, and Prosecution Bureau-BDocument2 paginiHon. Marco Anacleto P. Buena: Preliminary Investigation, Administrative Adjudication, and Prosecution Bureau-BGeramer Vere DuratoÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 226590, April 23, 2018 Shirley T. Lim, Mary T. Limleon and Jimmy T. Lim, Petitioners, V. People of THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent. DecisionDocument4 paginiG.R. No. 226590, April 23, 2018 Shirley T. Lim, Mary T. Limleon and Jimmy T. Lim, Petitioners, V. People of THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent. DecisionVanessa MallariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Verification Certification of Non-ForumshoppingDocument2 paginiVerification Certification of Non-ForumshoppingRaymarc Elizer AsuncionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application Form For Registration of Job ContractingDocument1 paginăApplication Form For Registration of Job ContractingKris Borlongan100% (1)

- Waiver Release and QuitclaimDocument2 paginiWaiver Release and QuitclaimAnonymous KZEIDzYrOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petition For A Notarial CommissionDocument5 paginiPetition For A Notarial CommissionMarion JossetteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updating The Account During The Grace Period and Before Actual Cancellation ofDocument4 paginiUpdating The Account During The Grace Period and Before Actual Cancellation ofGlenn Rey D. AninoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notice of Dishonor MOLINADocument1 paginăNotice of Dishonor MOLINAFLORENCIO jr LiongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spa - CaDocument2 paginiSpa - CaMJ CarreonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit Complaint-April Joy QuillaDocument9 paginiAffidavit Complaint-April Joy QuillaBai Alefha Hannah Musa-AbubacarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cash Bond FormDocument9 paginiCash Bond FormArgel Joseph Cosme100% (1)

- Articles of PartnershipDocument3 paginiArticles of PartnershipJem PagantianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judicial Affidavit TemplateDocument9 paginiJudicial Affidavit TemplateLizzette Dela PenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Verification NLRCDocument2 paginiVerification NLRCAndre CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Position Paper Draft SampleDocument10 paginiPosition Paper Draft SampleImman DCPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reconsitution of TitleDocument4 paginiReconsitution of Titlemkab100% (1)

- LETTER of COMPLAINT To Air Force Provost MarshallDocument4 paginiLETTER of COMPLAINT To Air Force Provost MarshallMuhammad Abundi Malik100% (1)

- Position Paper (Daniel Vitero Cederia) v2Document6 paginiPosition Paper (Daniel Vitero Cederia) v2jsmaguddatuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formal-Offer-of-Evidence Respondent Declaration of Nullity of MarriageDocument2 paginiFormal-Offer-of-Evidence Respondent Declaration of Nullity of MarriageMan HernandoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notice of Death ScribdDocument1 paginăNotice of Death ScribdDkboi GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Verification and Certification On Non-Forum ShoppingDocument1 paginăSample Verification and Certification On Non-Forum ShoppingRomualdo BarlosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Deed of Absolute Sale of SharesDocument3 paginiSample Deed of Absolute Sale of SharesGela Bea BarriosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retainer Agreement: Know All Men by These PresentsDocument2 paginiRetainer Agreement: Know All Men by These Presentsdouglas100% (1)

- Affidavit Adverse ClaimDocument2 paginiAffidavit Adverse ClaimDoan BalboaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rules On Venue of Filing Labor Cases: Complainant /petitionerDocument1 paginăRules On Venue of Filing Labor Cases: Complainant /petitionerLTB mtlawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secretary's CertificateDocument2 paginiSecretary's CertificateRhyz Taruc-ConsorteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Legal Consequences of Retrenchment and Legal Termination of EmploymentDocument6 paginiThe Legal Consequences of Retrenchment and Legal Termination of EmploymentHector Jamandre DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estafu Thru Falsification of Commercial DocumentDocument2 paginiEstafu Thru Falsification of Commercial DocumentnamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secretary's Certificate (To File Foreclosure)Document1 paginăSecretary's Certificate (To File Foreclosure)Joann LedesmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Board Resolution - Meyers (NLRC Orbiter Case)Document2 paginiBoard Resolution - Meyers (NLRC Orbiter Case)Gigi De LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- BP 22 - Notice of DishonorDocument5 paginiBP 22 - Notice of DishonorBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amada Resterio Vs People of The PhilippinesDocument2 paginiAmada Resterio Vs People of The PhilippinesArthur Archie TiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06 - Batas Pambansa Bilang 22Document20 pagini06 - Batas Pambansa Bilang 22Aaron MañacapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurisprudence - Notice of DishoorDocument4 paginiJurisprudence - Notice of DishoorMarky CieloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of UndertakingDocument1 paginăAffidavit of UndertakingBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Bar of The PhilippinesDocument3 paginiIntegrated Bar of The PhilippinesBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample NDADocument3 paginiSample NDABam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Bar of The PhilippinesDocument3 paginiIntegrated Bar of The PhilippinesBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion To Release VehicleDocument2 paginiMotion To Release VehicleBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Bar of The PhilippinesDocument3 paginiIntegrated Bar of The PhilippinesBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRIMPRO - 110 Complaint or InformationDocument12 paginiCRIMPRO - 110 Complaint or InformationBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- COMM NotesDocument22 paginiCOMM NotesBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Release, Waiver, Quitclaim Agreement: - (PHP - ) Which Is in Full and FinalDocument2 paginiRelease, Waiver, Quitclaim Agreement: - (PHP - ) Which Is in Full and FinalBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crimpro DigestsDocument19 paginiCrimpro DigestsBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition, Distinction and Classification: The Law On Public OfficersDocument34 paginiDefinition, Distinction and Classification: The Law On Public OfficersBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acknowledgement ReceiptDocument1 paginăAcknowledgement ReceiptBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Sports in ThailandDocument2 paginiHistory of Sports in ThailandBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRIMPRO 113 ArrestDocument9 paginiCRIMPRO 113 ArrestBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- COMM NotesDocument22 paginiCOMM NotesBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Remedial Law Review SyllabusDocument11 paginiRemedial Law Review SyllabusBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal Procedure Syllabus University of The Philippines Prof. Tranquil S. Salvador IIIDocument3 paginiCriminal Procedure Syllabus University of The Philippines Prof. Tranquil S. Salvador IIIEins BalagtasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capa V. Court of Appeals FactsDocument34 paginiCapa V. Court of Appeals FactsBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule 1-10Document86 paginiRule 1-10Bam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule 15-21Document29 paginiRule 15-21Bam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition, Distinction and Classification: The Law On Public OfficersDocument34 paginiDefinition, Distinction and Classification: The Law On Public OfficersBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- USI - Certification On Litigation, Proceeding and Litigation (FINAL)Document3 paginiUSI - Certification On Litigation, Proceeding and Litigation (FINAL)Celestino LawÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - Specimen Signature Template PDFDocument1 pagină1 - Specimen Signature Template PDFBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition, Distinction and Classification: The Law On Public OfficersDocument34 paginiDefinition, Distinction and Classification: The Law On Public OfficersBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal Procedure Syllabus University of The Philippines Prof. Tranquil S. Salvador IIIDocument3 paginiCriminal Procedure Syllabus University of The Philippines Prof. Tranquil S. Salvador IIIEins BalagtasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acknowledgement ReceiptDocument1 paginăAcknowledgement ReceiptBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acknowledgement ReceiptDocument1 paginăAcknowledgement ReceiptBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- AglipayDocument2 paginiAglipayBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Requirements For Transfer of TitleDocument1 paginăRequirements For Transfer of TitleBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Requirements For Transfer of TitleDocument1 paginăRequirements For Transfer of TitleBam SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comment: (To The Entry of Appearance With Manifestation and Motion)Document3 paginiComment: (To The Entry of Appearance With Manifestation and Motion)RTC Br. 110 Tarlac CityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maderada Vs MediodeaDocument7 paginiMaderada Vs MediodeaheyoooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dreamwork Construction Inc. V Janiola G.R. No. 184861 30 June 2009 FactsDocument2 paginiDreamwork Construction Inc. V Janiola G.R. No. 184861 30 June 2009 FactsJeoffry Daniello FalinchaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 CIR V JavierDocument11 pagini11 CIR V JavierNeil BorjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grego V COMELEC DigestDocument2 paginiGrego V COMELEC DigestKaren HaleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Torres V JavierDocument7 paginiTorres V JavierJethro KoonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jesus M. Aguas For Petitioner. The Solicitor General For RespondentsDocument57 paginiJesus M. Aguas For Petitioner. The Solicitor General For RespondentsRonalyn Bergado LucenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Times Leader 02-10-2012Document34 paginiTimes Leader 02-10-2012The Times LeaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application of Doctrine of Proportionality in Administrative LawDocument6 paginiApplication of Doctrine of Proportionality in Administrative LawAyush Kumar SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- DPC ProjectDocument17 paginiDPC ProjectLucky RajpurohitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moniz 08-0344Document5 paginiMoniz 08-0344kevinhfdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Naylor v. Daly Respondant's Brief On The Merits - 10172011Document115 paginiNaylor v. Daly Respondant's Brief On The Merits - 10172011Daniel WilliamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurisdiction in Enrica Lexi CaseDocument12 paginiJurisdiction in Enrica Lexi CaseAdhithyan S KÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2006 194A AN 13620 M - Section7Document299 pagini2006 194A AN 13620 M - Section7main_justiceÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 v13 PiDocument145 pagini2013 v13 PiJessica ArtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memorial For PetitionersDocument34 paginiMemorial For PetitionerskunalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dokis First Nation Draft Constitution July 12 2016Document12 paginiDokis First Nation Draft Constitution July 12 2016Sharon RestouleÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument22 paginiUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rodil Vs Benedicto Actual CaseDocument3 paginiRodil Vs Benedicto Actual Casemaanyag6685Încă nu există evaluări

- The Italian Transition After The Second PDFDocument31 paginiThe Italian Transition After The Second PDFFarid BenavidesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4th Exam Report - Cabales V CADocument4 pagini4th Exam Report - Cabales V CAGennard Michael Angelo AngelesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Section 138 of Ni ActDocument6 paginiSection 138 of Ni Actshailesh nehra100% (1)

- Complaint - Fairbanks v. Roller (1 June 2017) - RedactedDocument13 paginiComplaint - Fairbanks v. Roller (1 June 2017) - RedactedLaw&CrimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Williams V WilliamsDocument3 paginiWilliams V WilliamsAdom PolkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diaz v. RepublicDocument15 paginiDiaz v. Republiccarla_cariaga_2Încă nu există evaluări

- RP v. Sandiganbayan - CaseDocument25 paginiRP v. Sandiganbayan - CaseRobehgene Atud-JavinarÎncă nu există evaluări

- NJ Supreme Court: State v. Gary LunsfordDocument56 paginiNJ Supreme Court: State v. Gary LunsfordAsbury Park PressÎncă nu există evaluări

- Markeith Loyd Death Penalty Trial: Motion Compel Orlando Police Department Internal Affairs Material Re FDLEDocument31 paginiMarkeith Loyd Death Penalty Trial: Motion Compel Orlando Police Department Internal Affairs Material Re FDLEReba KennedyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Del Prado Vs Santos G.R. No. L-20946 Sept 23, 1966Document2 paginiDel Prado Vs Santos G.R. No. L-20946 Sept 23, 1966Victoria Quindara ParagguaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labor Law Arbitration 2016Document168 paginiLabor Law Arbitration 2016Libay Villamor IsmaelÎncă nu există evaluări