Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Jurnal Forensik

Încărcat de

Nadia OktarinaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Jurnal Forensik

Încărcat de

Nadia OktarinaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Articles

Oxford, Oxford, UK

(S Mallet DPhil); Leeds General

Infi rmary, Leeds, UK

(T Patankar FRCR); Department of Radiology, Southampton

General Hospital,

Southampton, UK

(C Peebles FRCR); and Peninsula Medical School, University of

Plymouth, Plymouth, UK

(Prof C Roobottom FRCR)

Lancet 2012; 379: Correspondence to:

13642 Prof Ian S D Roberts, Department of Cellular Pathology, John

Published Online Radcliff e Hospital, Headington,

November 22, 2011 Oxford OX3 9DU, UK ian.roberts@ouh.nhs.uk

Post-mortem imaging as an alternative to

DOI:10.1016/S0140-

6736(11)61483-9

See Comment page

Department of

100

autopsy in the diagnosis of adult deaths: a

Cellular

Pathology, John

Radcliff e

validation study

Hospital, Oxford, UK

(Prof I S D Roberts

Ian S D Roberts, Rachel E Benamore, Emyr W Benbow, Stephen H Lee, Jonathan N Harris, Alan Jackson, Susan Mallett,

FRCPath); Tufail Patankar, Charles Peebles, Carl Roobottom, Zoe C Traill

Department of

Radiology,

Summary

Churchill Hospital, Background Public objection to autopsy has led to a search for minimally invasive alternatives. Imaging has

Oxford, UK

potential, but its accuracy is unknown. We aimed to identify the accuracy of post-mortem CT and MRI compared

(R E Benamore FRCR,

Z C Traill FRCR);

with full autopsy in a large series of adult deaths.

Department of

Histopathology Methods This study was undertaken at two UK centres in Manchester and Oxford between April, 2006, and

(E W Benbow FRCPath) November, 2008. We used whole-body CT and MRI followed by full autopsy to investigate a series of adult deaths

and

that were reported to the coroner. CT and MRI scans were reported independently, each by two radiologists who

Department of

were masked to the autopsy fi ndings. All four radiologists then produced a consensus report based on both

Radiology techniques, recorded their confi dence in cause of death, and identifi ed whether autopsy was needed.

(S H Lee FRCR), Findings We assessed 182 unselected cases. The major discrepancy rate between cause of death identifi ed by

Manchester Royal

Infi rmary, radiology and autopsy was 32% (95% CI 2640) for CT, 43% (3650) for MRI, and 30% (2437) for the consensus

Manchester, radiology report; 10% (317) lower for CT than for MRI. Radiologists indicated that autopsy was not needed in 62

(34%; 95% CI 2841) of 182 cases for CT reports, 76 (42%; 3549) of 182 cases for MRI reports, and 88 (48%;

UK; Department of

Radiology,

4156) of 182 cases for consensus reports. Of these cases, the major discrepancy rate compared with autopsy was

Hope Hospital, 16% (95% CI 927), 21% (1332), and 16% (1025), respectively, which is signifi cantly lower (p<00001) than for

Salford, UK cases with no defi nite cause of death. The most common imaging errors in identifi cation of cause of death were

(J N Harris FRCR); ischaemic heart disease ( n=27), pulmonary embolism (11), pneumonia (13), and intra-abdominal lesions (16).

Department of

Neuroradiology, The

University of Interpretation We found that, compared with traditional autopsy, CT was a more accurate imaging technique

Manchester, than MRI for providing a cause of death. The error rate when radiologists provided a confi dent cause of death

Manchester, UK

was similar to that for clinical death certifi cates, and could therefore be acceptable for medicolegal purposes.

(Prof A Jackson FRCR);

Department of However, common causes of sudden death are frequently missed on CT and MRI, and, unless these weaknesses are

Primary Care addressed, systematic errors in mortality statistics would result if imaging were to replace conventional autopsy.

Health Science,

University of

Funding Policy Research Programme, Department of Health, UK.

www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012 1

Articles

Introduction A post-mortem MRI service for selected non-suspicious

Traditional autopsy has changed little in the past century, deaths was introduced in Manchester, UK, in the 1990s, in

response to demand from the Jewish community and,

consisting of external examination and evisceration,

subsequently, by the much larger Muslim community in the

dissection of the major organs with identifi cation of

northwest of England. Radiologists provide a cause of

macroscopic pathologies and injuries, and histopathology if death that is accepted by the Coroner with no autopsy in

needed. In the UK, concerns exist about the large number 90% of cases.6 Despite this application of post-mortem

of autopsies done (22% of deaths), and their adequacy. The MRI, few studies have investigated the accuracy of imaging

reductions in consent for hospital autops ies, which might in the diagnosis of the cause of adult deaths. Findings from

partly indicate clinical disinterest, 1 have not been a small study7 of ten cases, in which postmortem MRI was

followed by full autopsy, showed important weaknesses of

accompanied by a fall in the number of medicolegal

imagingnotably, an inability to detect arterial occlusions

autopsies. A review of coroners services2 questioned the and to diff erentiate between pulmonary oedema and

justifi cation of such high numbers of autopsies, and a pneumonia. Weustink and colleagues8 reported similar fi

national audit criticised the number of poor and inadequate ndings in a sample of 30 adult deaths. In 2006, the

autopsy reports.3 Longstanding public objection to Department of Health commissioned two post-mortem

dissection of cadavers re-emerged in the UK as a major imaging studies, one in adults and one in neonates and

issue after organ retention scandals in the late 1990s. Some children. We report the fi ndings of the adult study.

groups notably Jewish and Muslim communitieshave We aimed to assess: the accuracy of post-mortem imaging

religious objections to autopsy,4 and demand for a in diagnosis of cause of death in adults; whether

minimally-invasive alternative has increased. This demand radiologists can accurately identify which cases might be

has been acknowledged in the Coroners and Justice Act

2009.5

2 www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012

Articles

diagnosed with post-mortem imaging and therefore would case alternately (including images of the rest of the body), See Online for

webvideo

not need full autopsy; the relative accuracy of CT and MRI and then produced a consensus report, including cause of

in detecting post-mortem pathologies and cause of death; death, based on both techniques. This process resulted in 11

inter observer variation in radiological cause of death; and reports for each case: four independent general radiologist

whether accuracy is improved by use of specialist cardiac reports (two CT and two MRI), consensus MRI and CT

and neuroradiologists. reports, a consensus general radiologist report (MRI and

CT), three specialist cardiac reports (CT, MRI, and

Methods consensus), and one neuroradiology report. Once all reports

Study design were complete, we reviewed each case at meetings of the

All deaths were reported to the Oxford or Manchester study team, and compared the imaging with pathologists

Coroners between April 4, 2006, and November 26, 2008. autopsy fi ndings, which we used as the reference standard.

We selected for inclusion the fi rst case referred each study We repeated this process 13 times in batches of ten to 20

day, to ensure no selection bias; timing of case referral to cases. Meetings were held between January, 2007, and

the coroners offi ce is random. We predetermined study November, 2010.

days according to availability of radiology and pathology Bodies were imaged in sealed body bags in the supine

staff . Exclusion criteria were failure to obtain consent for position, with arms adjacent to the body. CT images were

imaging and severe obesity (patients weighing more than acquired on an eight-slice multidetector scanner in Oxford,

100 kg). Cases were otherwise unselected, which ensured a

and on a 16-slice multidetector scanner in Manchester. At

representative coronial casemix. The study received ethics

both centres, contiguous 375 mm axial images were

approval (Central Offi ce for Research Ethics Committee

reference 04/Q1604/56). obtained through the brain at 120 kV and variable mAs,

with a window level of 40 Hounsfi eld units (HU) and a

Procedures width of 80 HU. Volumetric scans were obtained from the

Radiologists did post-mortem MRI and CT out-of-hours vertex to the symphysis pubis at 120 kV with variable mAs,

(before 0700 h or after 1800 h) in the departments of a pitch of 1675:1, and 0625 mm collimation. Images were

radiology at the Churchill Hospital, Oxford, UK, and at reconstructed with a soft tissue algorithm to provide 5 mm

Manchester Royal Infi rmary. Pathologists did full autopsy and 125 mm slices, and viewed on standard window

after imaging. The workload and casemix at both centres is settings for soft tissue, lung, and bone. See webvideo for an

typical of large city mortuaries in the UK. For cases used example of a post-mortem CT scan. MRI sequences were

for analysis we provided two experienced general cross- sagittal T1-weighted, coronal dual echo and axial fast short

sectional radiologists with either CT or MRI scans for each tau inversion recovery (STIR) images of the brain, and

case alternately, together with the clinical history and axial T1-weighted and T2 fast spin echo and coronal T1

circumstances of death from the coroners offi ce. The and STIR images of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

radiologists, as part of their daily workload, routinely report After we reviewed the fi rst 30 patients, we replaced the

both body and neuro-

www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012 3

208 cases enrolled

Protocol for radiology reporting

Articles

cardiac radiologists; first 100

) cases Specialist cardiac radiology report

(2

(2 ) cases

casesused

excluded

for training

16

neuroradiologists; all 182 cases 10

Specialist neuroradiology report

radiological CT and MRI. The two Manchester-based radiologists had substantial experience of reporting postmortem MRI, but no experience of

post-mortem CT. The two Oxford-based radiologists had no previous experience of post-mortem scanning, which would be typical of a general

radiologist at this time. Each radiologist independently completed a reporting proforma. The two radiologists receiving scans from the same

imaging modality then produced a consensus report, resulting in independent consensus CT and MRI reports for each case. All four radiologists

then reviewed both modalities and reached a consensus about the diagnoses. This report included a formulation of cause of death, an indication of

radiological confi dence (defi nite, probable, possible, or unascertained), and whether, in a routine service, autopsy would be needed.

Independent of the general radiology reports, brain imaging was reported by two specialist neuroradiologists who described the pathologies, but

did not review the remainder of the imaging to formulate a cause of death. For the fi rst 100 cases, two specialist cardiac radiologists

independently reviewed the CT or MRI images for each

Figure 1:

general radiologists, consensus MRI report independe

general ra

(4

MRI+CT) (2

Consensus radiology report 1

1

consensus

4 www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012

Articles

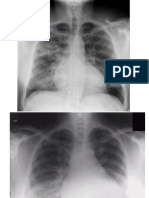

(A) Axial CT image through the upper abdomen showing extensive intravascular gas proportions with the Wilson method. 13 We used Stata

(arrowhead), in keeping with decomposition. Free intraperitoneal gas (arrow) is due to (version 11.0) for other statistical methods. We used

decomposition in this patient, but creates diffi culty for exclusion of a perforated

intra-abdominal viscus. (B) Axial CT image through the brain showing extensive

McNemars test to calculate p values for paired

intracranial gas due to decomposition. Diff erentiation between grey and white matter proportions, and tests for p values of unpaired

is poor. (C) Axial CT image showing rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm proportions. Because no fi xed categories are available for

(arrowhead) with extensive retroperitoneal haemorrhage on the left (arrow). (D) reasons of death, calculation of values was not

Oblique axial (short-axis view) T2-weighted MRI image showing a haemopericardium ( appropriate for analysis of interobserver variation between

arrowhead) due to rupture of a myocardial infarct (arrow ).

independent radiology reports.

Circumstances of death and indications for coronial referral 182 (1%

) 2 (1%

)

Role of the funding source

Total Suspected drug-related death Suspected industrial disease

Table 1: The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data

collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of

the report.

Results

Figure 1 shows the protocol for radiology reporting. We

enrolled 208 cases, of which we excluded 15 because of an

incomplete imaging procedure (breakdown of MRI or CT

scanners, incomplete dataset, or disk failure), and one

because the body had been embalmed before examination.

We used the fi rst ten cases for training purposes, to

familiarise the radiologists with post-mortem changes ( fi

gure 2), leaving 182 cases for analysis.

fl uid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence,

The most common indication for coronial referral is

and obtained a T2-weighted short-axis oblique axial

sudden death of unknown cause (table 1); as such, the most

sequence through the heart. Full autopsies were done

common cause of death was cardiovascular disease (table

within 12 h of imaging by six senior consultant

2). The major discrepancy rate compared with autopsy was

pathologists. Specimens were obtained for histology and

signifi cantly higher (p=00046) for MRI than for CT and

toxicology assessments as needed.

consensus reports (table 3). We noted 10% (95% CI 317)

We present analysis of cause of death data only; the more major discrepancies for MRI than for CT, and 13%

detection of incidental lesions not contributing to death is (619) more for MRI than for consensus reports (table 3).

beyond the functions of the coroners autopsy. Radiologists Similarly, in cases with a defi nite radiological cause of

and pathologists formulated cause of death according to death, the major discrepancy rate compared with autopsy

Offi ce for National Statistics guidance. 9 We subclassifi ed was higher for MRI than for CT and consensus reports

radiology and autopsy causes of death according to type of (table 3); however, because of the small number of cases,

pathology and organ involved. We classifi ed discrepancies this diff erence was not signifi cant (MRI vs CT p=0542;

between radiology and autopsy cause of death as none, MRI vs consensus reports p=0481). Analysis of

minor, or major, with major indicating involvement of diff interobserver variation showed that, with exclusion of cases

erent pathologies or organs. Minor discrepancies were in which one or both radiologist gave the cause of death as

variations within a pathology or organ system that would unascertained, there was a major discrepancy between the

be of little relevance for the coroners investigation or for radiologists cause of death by CT and MRI in about a

national mortality statistics (eg, ischaemic heart disease vs quarter of cases (table 4).

acute myocardial infarction). Major discrepancies (eg,

Levels of confi dence for the consensus radiology

pulmonary embolism vs myocardial infarction) would aff

reports were defi nite for 88 (48%) of 182 cases,

ect national mortality statistics, but would not necessarily

probable for 52 (29%) cases, possible for 29 (16%)

result in a diff erent verdict by the coroner. We used this

cases, and unascertained for 13 (7%) cases. The

defi nition of major discrepancy rather than one that would

proportion of cases in which a defi nite cause of death

change the coroners verdict because no legal defi nition

was provided was 14% (95% CI 621) higher for

exists of natural and unnatural cause of death. The verdict

consensus reports than for CT reports (p=00005), and

for a specifi c cause of death is open to interpretation, and

6% (0513) higher for consensus reports than for MRI

there is much variation between diff erent coroners. 10

reports (p=005; table 3). The proportion of defi nite

causes of death did not diff er signifi cantly between CT

Statistical analysis and MRI reports (8% diff erence, 95 % CI 116,

We used CIA software (Trevor Bryant version 2.1.2) 11 to calculate 95% CIs for p=0124; table 3).

paired and unpaired proportions with the Newcombe method, 12 and for single

www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012 5

Articles

Post-mortem changes and pathologies DA B

Major discrepancies between radiological and autopsy cause of death were death for the fi rst six batches

reduced when radiologists indicated that autopsy was not necessary (table 3). Major formulation errors are

either unsupported modes of

When radiologists confi dence was defi nite, the proportion of cases with a major death or sequence errors for

discrepancy compared with autopsy was 25% less than the non-defi nite cases for which no logical causal relation

CT (95% CI 1137; p=00006), 37% less for MRI (2349; p<00001), and 28% exists between parts Ia, b, and c

less for consensus reports (1544; p<00001; table 3). The major discrepancy rate of the medical certifi cate of

between consensus radiological and autopsy causes of death did not improve with cause of death.

C

increased experience of comparison between radiology and autopsy (data not

shown). All radiologists showed improvement in their formulation of cause of

Missed Ove

death, although the frequency of major formulation errors, such as sequence on ed o

errors and unsupported modes of death (fi gure 3), and rate of improvement (data imaging imag

not shown) diff ered between radiologists. Coronary heart 12/86 (14%) 15 /9

General radiologists requested a neuroradiology report in six of 182 cases. In disease

Pulmonary embolism 10/10 (100%) 1 /1

four of these cases, a CNS disorder was included in the autopsy cause of death.

Bronchopneumonia 9/28 (32%) 4 /2

Only one case had a major discrepancy between autopsy and general radiology

Intestinal infarction 4/6 (67%) 1 /3

cause of death; a case of bacterial meningitis missed on imaging in which the

neuroradiologists also reported the brain as normal. In a further 15 cases, CNS Data are n/N (%). Denominators for the left-hand

are total diagnoses of these disorders in the autop

disorders were included in the cause of death; the most common pathologies were

of death. Denominators in the right-hand column

cerebral

Figure 2: infarction (four cases), total diagnoses of these disorders in the consensu

head injury with intracranial CT MRI Consensus radiology causes of death.

haemorrhage (three), and CT and MRITable 5: Most common sources of major dis

subarachnoid haemorrhage Major discrepancy rate with 32% (2640) 43% (3650) 30 % (24between autopsy and consensus radiolog

of death

(three). In none would the autopsy cause of death, all 37)

to

neuroradiologists report have cases (%)

Proportion of cases with defi 34% (2841) 42% (3549) 48 % (41

altered the general radiologists nite radiological cause of 56)

cause of death. death, no autopsy needed

We recorded a major (%)

discrepancy between consensus Major discrepancy rate with 16% (927) 21% (1332) 16 % (10

cardiac radiology and autopsy autopsy when radiologist confi 25)

dence is defi nite (%)

causes of death in 30 (31%, 95% Major discrepancy rate with autopsy when 41% (3350) 59%

CI 2341) of 97 cases, compared (4967) 44 % (3454)

with 31 (32%, 2442) cases for the radiologist confi dence is not defi nite (%)

general radiologists. Cardiac

Data are % (95% CI) or number (%, 95% CI). Percentages are rounded to nearest whole

radiologists provided a defi nite number.

cause of death in 36 (38%, 3049) Table 3: Major discrepancy rate between autopsy and radiology cause of Autopsy causes of death by type of pat

medical

femur, one

certifi

multiple

cate ofinjuries.

cause of death. *Three hea

of 97 cases and, in this group, fi ve death Table

Totals 2:

exceed 182 because several pathologies w

Tot

(14%, 629) of 36 showed a major discrepancy with autopsy cause of death. malignancy (three bronchial

Imaging was sensitive in the detection of internal haemorrhage, with the consensus carcinomas, two pancreatic

radiology reports correctly identifying all ten cases of haemopericardium (six carcinomas, two colonic

ruptured myocardial infarct, four ruptured aortic aneurysm and dissection), six carcinoma, one mesothelioma,

ruptured aortic aneurysms, and four intracranial haemorrhage (fi gure 2). In two one carcinoma of gall bladder, one

cases of haemopericardium, the radiologists incorrectly attributed haemorrhage to a pharyngeal carcinoma). The

ruptured aortic aneurysm or dissection rather than myocardial infarct, and two of colonic carcinomas were not

three cases of subarachnoid haemorrhage were identifi ed on CT but not MRI. In ten identifi ed on imaging. Carcinoma

cases, autopsy attributed death of gall bladder was misidentifi ed

as duodenal carcinoma; the

pancreatic tumours were also

misidentifi ed, one with

pulmonary metastases diagnosed

as pulmonary malignancy, the

other with hepatic metastases as

hepatic abscesses. The other

malignancies were correctly

diagnosed on consensus imaging,

6 www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012

Articles

although one bronchial carcinoma was correctly reported cranial cavity, this scenario is not the case in routine

with MRI but not with CT. coronial practice. The standard of autopsies is highly

The most common major discrepancies were in the diagnosis of pulmonary variable. In a UK-wide audit, one in four autopsy reports

embolism, coronary heart disease, pneumonia, and intestinal infarction (table 5). Of were regarded as poor or inadequate. 2 The post-mortem

97 cases reported by the cardiac radiologists, death was attributed to pulmonary report can be audited, but the adequacy of the procedure

embolism at autopsy in seven. None was diagnosed by the general radiologists, but cannot. Tissue is retained for histology in only a few

three autopsies, and in even fewer is there a photographic

(43%) were correctly identifi ed by the cardiac radiologists. However, death was record of the macroscopic pathologies; in most cases, no

misattributed to pulmonary embolism by the cardiac radiologists in fi ve cases and method is available to review fi ndings. However, a

by the general radiologists in one case. Radiologists frequently interpreted permanent record is available for imaging; therefore, this

pneumonic consolidation as pulmonary oedema secondary to cardiac failure (table technique could be a way to audit autopsy practice. The

5). Other diagnoses missed on imaging were cases of pancreatitis, perforated major discrepancy rate in cause of death provided by

duodenal ulcer, acute asthma, and overwhelming sepsis with adult respiratory radiologists reporting the same technique was 2226%.

distress syndrome (data not shown). One case of cerebellar infarction reported with The destructive nature of traditional autopsy means that

imaging was not detected at autopsy. Autopsy attributed death to ileal infarction due reproducibility

Frequ Frequency

4 offormulation

of diagnosiserrors

of pathological changes causes

in the general radiologist is of

ency

to emboli from the heart because of cardiac amyloidosis. Neither disorder was diffi cult(%to

) assess. However, autopsy cannot be assumed

diagnosed with imaging. to be better than imaging; the conclusions of a

pathologist doing a second autopsy frequently diff er to

Discussion those of the fi rst.

Our results show that, in a series of unselected deaths referred to the coroner, a Which imaging technique should be used? Forensic

major discrepancy exists between autopsy and imaging causes of death in 30% of practices use CT because it provides 3 better spatial

cases. Overall, CT was more accurate than MRI in identifi cation of cause of death; resolution than MRI and40 is eff ective for showing

the major discrepancy rate compared with autopsy was signifi cantly higher for MRI fractures and haemorrhages. Radiologist

Non-forensic and paediatric

than for CT and consensus reports. practices have used MRI30because it provides greater

Published work7,8,1416 comparing autopsy and imaging comprise mostly anecdotal detail of soft tissues than does CT. Our fi ndings show

reports or small case series, and the accuracy of imaging in detection of the wide that both techniques have strengths and

Reporting weaknesses

batch 4 50

range of pathological changes seen in coronial practice has not been examined eg, CT provides visualisation of coronary artery calcifi

Figure 3:

systematically. The most common reason for coronial referral is sudden death of cation that is not apparent with MRI, whereas acute

unknown cause. In this respect, our casemix is typical, with coronary heart disease myocardial infarcts might be seen with MRI but not with

being the most common autopsy diagnosis. In living patients, detection of vascular CT. Use of both techniques as a routine 2would have

events by cross-sectional imaging necessitates use of intravenous contrast resource implications and evidence

20 to support this use is

administration and, therefore, that the most frequent major errors were failure to scarce. We noted only two cases in this study in which a

detect arterial occlusion and infarcts is not surprising. Post-mortem angiographic major discrepancy existed with autopsy cause of death

techniques are being developed and validated 1719 to overcome this weakness. Other for both CT and MRI reports, but not for the consensus

defi c iencies of conventional cross-sectional imaging shown in this study could be radiology report.

overcome by combination of imaging modalities with minimally-invasive CT has important practical advantages, being more

techniques, such as needle biopsy.7,20,21 In a report22 of 20 non-traumatic deaths, widely available, less expensive, and quicker to do than

investigators recorded a good correl ation between CT combined with angiography MRI. CT could also be combined with angiography,

and needle biopsy and subsequent full autopsy; however, most causes of death increasing the accuracy of detection of vascular

provided in that study were modes of death that would not be accepted in the UK Panel: Research in context

legal system.

Post-mortem changes cause specifi c diffi culties for imaging diagnosis. Systematic review

Distinction of intra-abdominal gas due to putrefaction from antemortem perforation We searched Medline from Jan 1, 1980, to Aug 1,

of the stomach or bowel can be diffi cult, which resulted in a missed perforated 2011, for reviews and primary studies of post-

duodenal ulcer in our study. Similarly, the distinction of post-mortem clot from mortem imaging. We excluded studies of fetal

antemortem thrombus has not proved possible with cross-sectional imaging; a and paediatric autopsies and imaging of

missed diagnosis of pulmonary embolism was one of the most common errors in our removed organs. Our search terms virtopsy,

study. After use of the fi rst ten cases for training, comparison of the batches in virtual autopsy, minimally invasive autopsy,

which imaging was reported and reviewed showed an improvement in cause of post mortem angiography, post mortem

death formulation with increasing radiologist experience, but no reduction in the with imaging or CT or MRI, identifi ed 60

major discrepancy rate between radiology and autopsy cause of death. citations, which were mostly forensic case

We used full autopsy as the gold standard for diagnosis, but this assumption reports. Five small series7,8,1416 of non-violent adult

might not be valid. Imaging could be better than autopsy in detection of some deaths compared the diagnostic accuracy of

fractures, intracranial pathologies, and pneumothorax. We recorded one case in post-mortem imaging to traditional autopsy.

which a cerebellar infarct evident with imaging was missed at autopsy. Only one of these fi ve studies8the largest one

Furthermore, although all autopsies were complete, including exami nation of the with 30 patientscompared CT with MRI, but

www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012 7

Articles

full autopsy was done after imaging in only four cases. No study services for living patients are not

compared accuracy of CT cause of death with that based on MRI. disrupted. Service providers will

need training and assessment in

Interpretation the interpretation of post-mortem

Our fi ndings show that compared with autopsy, CT is more accurate imaging. Cost implications are

than MRI in determination of cause of death in adults, and that a also a concern; MRI in particular

major discrepancy exists in the cause of death provided by two is more expensive than is

radiologists reporting independently in a quarter of cases. When traditional autopsy. Further

radiologists are confi dent that the cause of death on imaging is defi development of postmortem

nite, the discrepancy rate between the radiological and autopsy imaging is needed and this

diagnoses is lower and might be acceptable from a medicolegal point development must be based on

of view. The radiologists ability to accurately identify cases for which careful consideration of

their diagnosis is correct is essential for the safe introduction of a comparisons between radiology

minimally invasive autopsy service. and autopsy.

Contributors

ISDR designed the study, assisted in data

collection and analysis, and drafted and

pathologies. If imaging were to be used as a pre-autopsy edited the manuscript. REB, EWB, SHL,

screening technique, the overall diagnostic accuracy is less JNH, AJ, TP, CP, CR, and ZCT assisted in

important than radiologists being able to identify those cases data collection and edited the manuscript.

SM assisted in data analysis and edited the

in which imaging can correctly diagnose the cause of death. In manuscript.

this study, radiologists indicated that autopsy was unnecessary

Confl icts of interest

to confi rm the cause of death in almost half of cases. The We declare that we have no confl icts of

major discrepancy rate between consensus imaging and interest.

autopsy in the group for whom autopsy was not necessary to Acknowledgements

confi rm cause of death could be acceptable for medicolegal UK Department of Health funded this study.

purposes because it is similar to the error rate of clinical death We thank Raymond FT

certifi cates on which most registered causes of deaths are McMahon, Richard Fitzmaurice, Lorna J

McWilliam (Manchester Royal Infi rmary),

based.23 However, because some disorders, such as pulmonary and Sanjiv Manek (John Radcliff e

emboli, could not be diagnosed, replacement of autopsy with Hospital, Oxford) for their assistance

imaging would result in systematic errors in mortality undertaking autopsies.

statistics. If used as a pre-autopsy screen, imaging might avoid References

unnecessary autopsies (eg, for ruptured aortic aneurysm), 1Tsitsikas DA, Brothwell M, Aleong JC, Lister AT. The attitudes of relatives

identify lesions diffi cult to diagnose by dissection, and help to autopsy: a misconception. J Clin Pathol 2011; 64: 41214.

2Luce T, Hodder E, McAuley D, et al. Death certifi cation and investigation

to guide dissection by identifi cation of pathologies needing in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The report of a Fundamental

further investigation. Therefore, imaging could reduce the Review 2003. June, 2003. http://www.archive2. offi cial-

number of invasive autopsies at the same time as improving documents.co.uk/document/cm58/5831/5831.pdf (accessed July 1,

2003).

their quality.

3The Coroners autopsy: do we deserve better? A report of the

The main purpose of a coroners autopsy is to exclude an National Confidential Enquiry into

unnatural death, which could be achieved without diagnosis of Patient Outcome and Death, 2006.

an accurate natural cause. Imaging alone cannot diagnose http://www.ncepod.org.uk/2006Report/

Downloads/Coronial Autopsy Report

biochemical and toxicological causes, and is poor in the 2006.pdf.

identifi cation of asphyxial deaths. A minimally invasive 4Geller SA. Religious attitudes and the autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984;

autopsy service should include careful external examination of 108: 49496.

the body by a pathologist to identify superfi cial signs of 5Parliament of the UK. Coroners and Justice Act 2009. 2009. http://

www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/25/pdfs/ukpga_20090025_en. pdf

injury not detected on imaging. We advocate a fl exible (accessed March 26, 2010).

multidisciplinary service in which the coroner consults with 6Bisset RAL, Thomas NB, Turnbull IW, Lee S. Postmortem examinations

the pathologist and radiologist to select the most appropriate using magnetic resonance imaging: four year review of a working

service. BMJ 2002; 324: 142324.

techniques to investigate each death.

7Roberts ISD, Benbow EW, Bisset R, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance

Our fi ndings identify important shortcomings of imaging in determining cause of sudden death in adults: comparison

crosssectional imaging in the diagnosis of cause of death in with conventional autopsy. Histopathology 2003; 42: 42430.

adults and provide the evidence needed to refi ne imaging 8Weustink AC, Hunink MGM, van Dijke CF, Renken NS, Krestin GP,

Oosterhuis JW. Minimally invasive autopsy: an alternative to

techniques and enable them to be safely introduced into conventional autopsy? Radiology 2009; 50: 897904.

autopsy services. Practical and clinical governance 9Offi ce for National Statistics Death Certifi cation Advisory Group.

considerations remain. Where will imaging be done? If Guidance for doctors certifying cause of death. April, 2005. http://

www.nc-hi.com/pdf%20fi les/certifi ers_guidance_v2_tcm69-21289.

clinical facilities are used, providers should ensure that pdf (accessed Aug 1, 2005).

8 www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012

Articles

10 Roberts ISD, Gorodkin LM, Benbow EW. What is a natural cause of death? A survey of how Coroners 18 Roberts ISD, Benamore RE, Peebles C, Roobottom C, Traill ZC.

in England and Wales approach borderline cases. J Clin Pathol 2000; 53: 36773. Diagnosis of coronary artery disease using minimally invasive autopsy:

11 Newcombe RG. Improved confi dence intervals for the diff erence between binomial proportions based evaluation of a novel method of post-mortem coronary CT

on paired data. Stat Med 1998; 17: 263550. angiography. Clin Radiol 2011; 66: 64550.

12 Wilson EB. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am Stat Assoc 1927; 19 Saunders SL, Morgan B, Raj V, Robinson CE, Rutty GN. Targeted

22: 20912. post-mortem computed tomography cardiac angiography: proof of

13 Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ. Statistics with confi dence. 2nd edn. Bristol: BMJ concept. Int J Legal Med 2011; 125: 60916.

20 Huston BM, Malouf NN, Azar HA. Percutaneous needle autopsy

books, 2000. sampling. Mod Pathol 1996; 9: 110107.

14 Patriquin L, Kassarjian A, OBrien M, Andry C, Eustace S. Postmortem whole-body magnetic 21 Foroudi F, Cheung K, Dufl ou J. A comparison of the needle biopsy

resonance imaging as an adjunct to the autopsy: preliminary clinical experience. post mortem with the conventional autopsy. Pathology 1995; 27: 79

J Magn Reson Imaging 2001; 13: 27787. 82.

15 Ros PR, Li KC, Vo P, Baer H, Staab EV. Pre-autopsy magnetic resonance imaging: initial experience. 22 Bolliger SA, Filograna L, Spendlove D, Thali MJ, Dirnhofer S, Ross S.

Magn Reson Imaging 1990; 8: 30308. Postmortem imaging-guided biopsy as an adjuvant to minimally

16 Thali MJ, Yen K, Schweitzer W, et al. Virtopsy, a new imaging horizon in forensic pathology: virtual invasive autopsy with CT and postmortem angiography: a feasibility

autopsy by postmortem multislice computed tomography (MSCT) and magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Roentgenol 2010; 195: 105156.

(MRI)a feasibility study. J Forensic Sci 2003; 48: 386403. 23 Roulson R, Benbow EW, Hasleton PS. Discrepancies between clinical

17 Ross S, Spendlove D, Bolliger S, et al. Postmortem whole-body CT angiography: evaluation of two and autopsy diagnosis and the value of post mortem histology; a meta-

contrast media solutions. AJR 2008; 190: 138089. analysis and review. Histopathology 2005; 47: 55159.

www.thelancet.com Vol 379 January 14, 2012 9

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Post Mortem CT With Targeted Coronary Angiog - 2017 - TheDocument10 paginiDiagnostic Accuracy of Post Mortem CT With Targeted Coronary Angiog - 2017 - ThewendellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nuclear Medicine in Urology and NephrologyDe la EverandNuclear Medicine in Urology and NephrologyP. H. O'ReillyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estudio - Ecologico - Collin Et Al 2008-Prostate Ca Mortality in The USA and UKDocument8 paginiEstudio - Ecologico - Collin Et Al 2008-Prostate Ca Mortality in The USA and UKAlan Daniel TrujilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Multi-Parametric MRI and TRUSDocument8 paginiDiagnostic Accuracy of Multi-Parametric MRI and TRUSSiti AlfianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promis TrialDocument8 paginiPromis TrialRubí BustamanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forensic RadiologyDocument12 paginiForensic RadiologywendellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hallifax Radiological Investigation of Pleural DiseaseDocument38 paginiHallifax Radiological Investigation of Pleural Diseaselaila.forestaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review: Measuring Radiographic Bone Density and Irregularity in Normal HandsDocument1 paginăBook Review: Measuring Radiographic Bone Density and Irregularity in Normal HandsAnonymous V5l8nmcSxbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physics and Medicine Imaging TechniquesDocument9 paginiPhysics and Medicine Imaging TechniquesGabriela Silva MartinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Namin FinalDocument26 paginiCase Namin FinalAngel Borbon GabaldonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020 POUT Adj Pt+Gem in UrothelialDocument10 pagini2020 POUT Adj Pt+Gem in UrothelialFilip IonescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Prevalence and Characterization of Simple Hepatic Cysts by Ultrasound ExaminationDocument1 paginăThe Prevalence and Characterization of Simple Hepatic Cysts by Ultrasound Examinationcesar140891Încă nu există evaluări

- JR TiwiDocument13 paginiJR TiwiRahmatullahPertiwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baumann 2016 IJROBP Development Validation of Bladder Contouring AtlasDocument9 paginiBaumann 2016 IJROBP Development Validation of Bladder Contouring AtlaszanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polonium-210 Poisoning: A Fi Rst-Hand Account: ArticlesDocument6 paginiPolonium-210 Poisoning: A Fi Rst-Hand Account: ArticlesHerdani RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emailing Nuclear Medicine - The Requisites 3rd EditionDocument606 paginiEmailing Nuclear Medicine - The Requisites 3rd EditionIrinaMariaStrugariÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Arthurs2015Document10 pagini4 Arthurs2015Vivi DeviyanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magnetic Resonance Angiography: Principles and ApplicationsDe la EverandMagnetic Resonance Angiography: Principles and ApplicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consensus Guidelines For Delineation of Clinical Target Volume For Intensity-Modulated Pelvic Radiotherapy in Postoperative Treatment of Endometrial and Cervical CancerDocument17 paginiConsensus Guidelines For Delineation of Clinical Target Volume For Intensity-Modulated Pelvic Radiotherapy in Postoperative Treatment of Endometrial and Cervical CancerJaime H. Soto LugoÎncă nu există evaluări

- EANM Bone Scintigraphy GL 2016Document16 paginiEANM Bone Scintigraphy GL 2016Rażyrard ReżererskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-s2.0-S0301562997002640-mainDocument8 pagini1-s2.0-S0301562997002640-mainjiangchen0111Încă nu există evaluări

- 247 2014 Article 3164Document7 pagini247 2014 Article 3164Fahmil AgungÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data 2018 TesslerDocument9 paginiACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data 2018 TesslerdianaveebaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- NRG Oncology Updated International ConsensusDocument12 paginiNRG Oncology Updated International Consensusyingming zhuÎncă nu există evaluări

- LancetradiacionDocument7 paginiLancetradiacionIbai ArregiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 5089595073927053379Document253 pagini1 5089595073927053379Ukik SaliroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnalul Clinic deDocument4 paginiJurnalul Clinic deIonescu RaduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nejmoa2304968 1Document12 paginiNejmoa2304968 1Piyush malikÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria On Metastatic Bone Disease: Key WordsDocument10 paginiACR Appropriateness Criteria On Metastatic Bone Disease: Key WordsFaisal Darmawan BrawidyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shi 2017Document8 paginiShi 2017Claudia Ivette Villarreal OvalleÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1201971216312206 MainDocument11 pagini1 s2.0 S1201971216312206 MainKumara DantaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sipola. Detection and Quantification of Rotator Cuff Tears With Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging - A ProsDocument9 paginiSipola. Detection and Quantification of Rotator Cuff Tears With Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging - A Prossteven saputraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thoracic Anterior Spinal Cord Adhesion Syndrome Imaging FindingsDocument7 paginiThoracic Anterior Spinal Cord Adhesion Syndrome Imaging Findingspaulina_810100% (1)

- Addition of The Fleischner Society Guidelines To Chest CT ExaminationDocument9 paginiAddition of The Fleischner Society Guidelines To Chest CT Examinationvictor ibarra romeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument3 paginiNew England Journal Medicine: The ofFahmi Nur AL-HidayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Information Resources For Nuclear MedicineDocument7 paginiInformation Resources For Nuclear MedicineBora NrttrkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radioisotopes in MedicineDocument5 paginiRadioisotopes in MedicineEnya BautistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revesion QuideDocument250 paginiRevesion QuideSama Diares100% (1)

- Mitochondrial Disorders in Neurology: Butterworth-Heinemann International Medical ReviewsDe la EverandMitochondrial Disorders in Neurology: Butterworth-Heinemann International Medical ReviewsEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- Molecular Medicine: Genomics to Personalized HealthcareDe la EverandMolecular Medicine: Genomics to Personalized HealthcareEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Dysphagia-Optimised Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy Versus Standard Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy in Patients With Head and Neck CancerDocument13 paginiDysphagia-Optimised Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy Versus Standard Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy in Patients With Head and Neck CancerStavya DubeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Ebm 2Document15 paginiJurnal Ebm 2Shadrina SafiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forensic Science InternationalDocument164 paginiForensic Science Internationalpdf crossÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing Radiology Reports in ChiropracticDocument6 paginiWriting Radiology Reports in ChiropracticRohit SagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- KDocument34 paginiKIfeanyi UkachukwuÎncă nu există evaluări

- TIRADS2017Document9 paginiTIRADS2017Eliana RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging - 2023 - HirschlerDocument21 paginiMagnetic Resonance Imaging - 2023 - HirschlerAndres Cardenas OsorioÎncă nu există evaluări

- CT of The Heart: U. Joseph Schoepf EditorDocument903 paginiCT of The Heart: U. Joseph Schoepf Editorruth_labella3653Încă nu există evaluări

- Fractal Analysis Differentiation of Nuclear and Vascular Patterns in Hepatocellular Carcinomas and Hepatic MetastasisDocument10 paginiFractal Analysis Differentiation of Nuclear and Vascular Patterns in Hepatocellular Carcinomas and Hepatic MetastasisGabriel IonescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ESUR guidelines for MRI evaluation of pelvic endometriosisDocument11 paginiESUR guidelines for MRI evaluation of pelvic endometriosisDanaAmaranducaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRI of the Spine: A Guide for Orthopedic SurgeonsDe la EverandMRI of the Spine: A Guide for Orthopedic SurgeonsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumour in A Hong Kong Community: The Clinical and Radiological FeaturesDocument9 paginiKeratocystic Odontogenic Tumour in A Hong Kong Community: The Clinical and Radiological FeaturesYenita AdetamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radiation Dose and Cancer Risk in RetrospectivelyDocument8 paginiRadiation Dose and Cancer Risk in RetrospectivelyCristiam Guillermo UzuriagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Skin Manifestations of Cocaine Use - YmjdDocument2 paginiSkin Manifestations of Cocaine Use - YmjdApple StarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renal Colic Imaging Trends and ControversiesDocument8 paginiRenal Colic Imaging Trends and ControversiesJorge Perez LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pet MriDocument9 paginiPet MriSloMilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outcomes Following Surgery For Colorectal Live 2016 International Journal ofDocument1 paginăOutcomes Following Surgery For Colorectal Live 2016 International Journal ofoomculunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radiol 2020191735Document10 paginiRadiol 2020191735guhan taraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Otitis ExternaDocument6 paginiOtitis ExternaNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brain Abscess Diagnosis and Management GuideDocument7 paginiBrain Abscess Diagnosis and Management GuideNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RADIODocument16 paginiRADIONadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Long Acting Risperidon Adn Oral Antipsycotics in Unstable SchizophrenDocument10 paginiLong Acting Risperidon Adn Oral Antipsycotics in Unstable SchizophrenLunaFiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 151 FullDocument22 pagini151 FullNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Reading-Smoking and AsthmaDocument13 paginiJournal Reading-Smoking and AsthmaNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antidepressants, Depression, and Venous Thromboembolism Risk: Large Prospective Study of UK WomenDocument9 paginiAntidepressants, Depression, and Venous Thromboembolism Risk: Large Prospective Study of UK WomenNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Behavioral Weight-Loss Intervention in Persons With Serious Mental IllnessDocument9 paginiA Behavioral Weight-Loss Intervention in Persons With Serious Mental IllnessNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mp201672a MolekularDocument9 paginiMp201672a MolekularNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15.14 Panic Disorder Resource STEINDocument90 pagini15.14 Panic Disorder Resource STEINNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CoverDocument1 paginăCoverNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wound AssesmentDocument3 paginiWound AssesmentNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hiv SifilisDocument6 paginiHiv SifilisNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- VDRL SifilisDocument3 paginiVDRL SifilisNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Number of Interviews Needed To Yield New.1Document6 paginiThe Number of Interviews Needed To Yield New.1Nadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AnakDocument2 paginiAnakNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test Sifilis IndiaDocument5 paginiTest Sifilis IndiaNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hiv Sifilis PDFDocument6 paginiHiv Sifilis PDFNadia OktarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joosten 2010 Malnutrition in Pediatric Hospital Patients Current IssuesDocument5 paginiJoosten 2010 Malnutrition in Pediatric Hospital Patients Current IssuesPutri Wulan SukmawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- FilessDocument12 paginiFilessangrainimaulidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faktor-Faktor Risiko Penularan Hiv-Aids Pada Laki-LakiDocument11 paginiFaktor-Faktor Risiko Penularan Hiv-Aids Pada Laki-LakiSulhah YuliawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gina Country Focused Activities: GINA Global Strategy For Asthma Management and PreventionDocument31 paginiGina Country Focused Activities: GINA Global Strategy For Asthma Management and PreventionJo MahameruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chest Pain Notes USMLE Step 3Document3 paginiChest Pain Notes USMLE Step 3kisria100% (1)

- Seronegative Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Refining The Value of "Non-Criteria" Antibodies For Diagnosis and Clinical ManagementDocument11 paginiSeronegative Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Refining The Value of "Non-Criteria" Antibodies For Diagnosis and Clinical ManagementMike KrikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrition and Diet Therapy: Classification of Essential NutrientsDocument66 paginiNutrition and Diet Therapy: Classification of Essential NutrientsChristine Joy Molina100% (1)

- AMC MCQ Recalls November 2013Document11 paginiAMC MCQ Recalls November 2013drtehreem80% (5)

- 111 10 PBDocument3 pagini111 10 PBrabia ToorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bloodborne Pathogens: NWSSB, Det. Corona Annual Sustainment Training Instructor: Richard Owens October 3, 2008Document50 paginiBloodborne Pathogens: NWSSB, Det. Corona Annual Sustainment Training Instructor: Richard Owens October 3, 2008jayand_net100% (1)

- English Eating Disorder Research PaperDocument7 paginiEnglish Eating Disorder Research PaperBrooke Van VeenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Students in High-Achieving Neighborhoods Who Spend Too Much Time On Homework Have More Health Problems, Stress, and Alienation From SocietyDocument3 paginiStudents in High-Achieving Neighborhoods Who Spend Too Much Time On Homework Have More Health Problems, Stress, and Alienation From Societyryan eÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetic Foot SyndromDocument121 paginiDiabetic Foot Syndrommuh. jafrhan fattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAB HRPB Protocol - July2019Document1 paginăSAB HRPB Protocol - July2019ching leeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dissertation SalmonellaDocument7 paginiDissertation SalmonellaWriteMyPaperCoCanada100% (1)

- Maternal and Child Nursing - Antepartum PeriodDocument102 paginiMaternal and Child Nursing - Antepartum Periodchuppepay50% (2)

- Personal Trainers Guide Clients' Health ScreeningsDocument18 paginiPersonal Trainers Guide Clients' Health Screeningsgrande napaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peace Corps Report of Dental Examination - PC-OMS-1790 Dental 08/2009Document4 paginiPeace Corps Report of Dental Examination - PC-OMS-1790 Dental 08/2009Accessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colic in Horse: A Presentation OnDocument32 paginiColic in Horse: A Presentation OnMuhammad Saif KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHNN211 Week 2 Health Care Delivery SystemDocument7 paginiCHNN211 Week 2 Health Care Delivery SystemABEGAIL BALLORANÎncă nu există evaluări

- J.T. Kent's Aphorisms and Precepts on Homoeopathic PhilosophyDocument98 paginiJ.T. Kent's Aphorisms and Precepts on Homoeopathic PhilosophyYaniv AlgrablyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dietary Self-Assessment Assignment Revised Fall 2018 1Document17 paginiDietary Self-Assessment Assignment Revised Fall 2018 1api-457891306Încă nu există evaluări

- CA DIAGNOSTIC TEST Copy 1Document11 paginiCA DIAGNOSTIC TEST Copy 1Ermita AaronÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ac EPTDocument29 paginiAc EPTNisa Nisa100% (2)

- Abstracts of Literature: Some of The Papers On The Family Which Have Appeared Since 1960Document7 paginiAbstracts of Literature: Some of The Papers On The Family Which Have Appeared Since 1960Fausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRA1Document33 paginiMRA1mnaz786Încă nu există evaluări

- GROUP 5-Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument116 paginiGROUP 5-Alzheimer's Diseasehanna caballoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preparation of Simarouba DecoctionDocument2 paginiPreparation of Simarouba DecoctionAnonymous oLEQGVbMKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postoperative Assessment, Management and Complications GuideDocument57 paginiPostoperative Assessment, Management and Complications GuideThon JustineÎncă nu există evaluări

- HemerroidDocument24 paginiHemerroidVina WineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Green Coffee Bean Extract As A Weight Loss Supplement 2161 0509 1000180 PDFDocument3 paginiGreen Coffee Bean Extract As A Weight Loss Supplement 2161 0509 1000180 PDFdorathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Head Trauma: Dr. Andy Wijaya, SpemDocument20 paginiHead Trauma: Dr. Andy Wijaya, SpemThomas AlbertÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blood Chemistry Test Values and Clinical SignificanceDocument3 paginiBlood Chemistry Test Values and Clinical SignificanceHal Theodore Maranian BallotaÎncă nu există evaluări