Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Acondroplasia

Încărcat de

Marcela AndradeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Acondroplasia

Încărcat de

Marcela AndradeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Health Supervision for Children With Achondroplasia

Committee on Genetics

This set of guidelines is designed to assist the nent forehead, a flattened midface, and an average-

pediatrician in caring for children with achondro- sized trunk. The head usually appears relatively

plasia confirmed by radiographs and physical fea- large compared with the body. The most common

tures. Although pediatricians usually first see complication, occurring in adulthood, is related to

children with achondroplasia during infancy, oc- lumbosacral spinal stenosis with compression of the

casionally they are called on to advise the pregnant spinal cord or nerve roots.5,6 This complication is

woman who has been informed of the prenatal usually treatable by surgical decompression, if diag-

diagnosis of achondroplasia or asked to examine nosed at an early stage.

the newborn to help establish the diagnosis. There- Children affected with achondroplasia fre-

fore, these guidelines offer advice for these situa- quently have delayed motor milestones, otitis me-

tions as well. dia, and bowing of the knees (Fig 7).7 Occasionally

Achondroplasia is the most common form of dis- in infancy or early childhood there is symptomatic

proportionate short stature. The diagnosis is based airway obstruction, development of thoracolum-

on very specific features on the radiographs, which bar kyphosis, symptomatic hydrocephalus, or

include a contracted base of the skull, a square shape symptomatic upper cord compression. Most indi-

to the pelvis with a small sacrosciatic notch, short viduals with achondroplasia are of normal intelli-

pedicles of the vertebrae, rhizomelic (proximal) gence and are able to lead independent and pro-

shortening of the long bones, trident hands, a normal ductive lives.6 Because of their disproportionate

length trunk, proximal femoral radiolucency, and, by short stature, however, a number of psychosocial

mid-childhood, a characteristic chevron shape of the problems can arise. Families can benefit from an-

distal femoral epiphysis. Hypochondroplasia and

ticipatory guidance and the opportunity to learn

thanatophoric dysplasia are part of the differential

from other families with children of disproportion-

diagnosis, but achondroplasia can be distinguished

ate short stature.

from these because the changes in hypochondropla-

The following guidelines are designed to help the

sia are miider and the changes in thanatophoric dys-

pediatrician care for children with achondroplasia

plasia are much more severe and invariably lethal.

and their families. Issues that need to be addressed at

Achondroplasia is an autosomal dominant disorder,

various age groups are discussed (Table). These

but approximately 75% of cases represent new dom-

guidelines are not appropriate for other chondrodys-

inant mutations. The gene for achondroplasia has

plasias, because each type has its own natural his-

recently been found. Achondroplasia is due to a

tory, complications, and specific guidelines. It is im-

change in the genetic information for fibroblast

portant that parents also consult a physician with

growth factor receptor 3. 2,3 Almost all of the muta-

experience and expertise concerning achondroplasia

tions have been found to occur in exactly the same

early in their childs development, because these

spot. Now that the gene has been found and the

guidelines are intended for the general pediatrician

mutation known, potential therapies and diagnostic

without such experience.

methodologies are likely to be developed. A great

deal is known about the natural history of the disor-

der that can be shared with the family. The average THE PRENATAL VISIT

adult height in achondroplasia is about 4 ft for both Pediatricians may be called upon to counsel a fam-

men and women (Figs 1 through 6).4 Other features ily in which a fetus has achondroplasia or is sus-

include disproportionate short stature, with shorten- pected to have achondroplasia. In some settings, the

ing of the proximal segment of the limbs, a promi- pediatrician will be the primary resource for coun-

seling a family. At other times, counseling may al-

The recommendations in this policy statement do not indicate an exclusive ready have been provided to the family by a clinical

course of treatment for children with genetic disorders, but are meant to geneticist and/or the obstetrician. Because of a pre-

supplement anticipatory guidelines available for treating the normal child vious relationship with the family, however, the pe-

Provided in the AAP publication, Guidelines for Health Supervision. They

are intended to assist the pediatrician in helping children with genetic diatrician may be called on to review this informa-

conditions to participate folly in life. Diagnosis and treatment of genetic tion and to assist the family in the decision-making

disorders are changing rapidly. Therefore, pediatricians are encouraged process.

to view these guidelines in light of evolving scientific information. The diagnosis of achondroplasia in the fetus is

Clinical geneticists may be a valuable resource for the pediatrician

seeking additional information or consultation. most often only made with certainty when one or

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright 0 1995 by the American Acad- both parents have this condition. In this circum-

emy of Pediatrics. stance the parents are usually knowledgeable about

PEDIATRICS Vol. 95 No. 3 March 1995 443

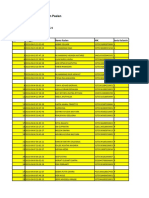

TABLE. Achondroplasia Guidelines for Health Supervision*

Infancy, 1 mo-1 y Early Childhood, 1-5 y Late Childhood Adolescence

Age (5-13 y), W-21 y),

Prenatal Neonatal 2 4 6 9 12 15 18 24 3y 4y Annual Annual

mo mo mo mo mo mo mo mo

Diagnosis

X-ray film Whenever the diagnosis is suspected.

Review phenotype Whenever the diagnosis is suspected.

Review proportions Whenever the diagnosis is suspected.

Genetic Counseling

Early intervention

Recurrence risks

Reproductive

options

Family support

Support groups

Long-term

planning

Medical Evaluation

Growth/weight/ 0

OFC

Orthopedic-if

complication

Neurologic-if

complication

Hearing OR OR OR OR

Social readiness S S S S

Orthodontics R R

Medical Evaluation

X-ray films-only

to make

diagnosis or if

complication

Ultrasound-of 0

brain ventricle

size

Social Adjustment

Psychosocial S S S S S

Behavior and s/o s/o s/o s/o s/o s/o s/o s/o s/o s/o

development

School 0 0 0

Sexualitv 0

* Assure compliance with the American Academy of Pediatrics Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care.

0 = to be performed; S = subjective, by history; 0 = objective, by a standard testing method; and R = discuss referral to a specialist.

the disorder, the inheritance, and the prognosis for 1. Review, confirm, and demonstrate laboratory or

the offspring. imaging studies leading to the diagnosis.

In most situations in which the parents have nor- 2. Explain the mechanisms for occurrence or recur-

mal stature, the diagnosis may only be suspected rence of achondroplasia in the fetus and the re-

based on the observation of disproportionately short currence risk for the family.

limbs in the fetus by ultrasound. With the frequent 3. At least 75% of cases of achondroplasia occur in

use of ultrasound, approximately one third of cases families in which both parents have average stat-

of fetal achondroplasia are suspected prenatally. ure and achondroplasia in the offspring occurs

However, disproportionately short limbs are ob- due to sporadic mutation in the gene.

served in a heterogeneous group of conditions. In the 4. Review the natural history and manifestations of

majority of these cases, the specific diagnosis cannot achondroplasia, including variability.

be made with certainty except by radiography late in 5. Discuss further studies that should be done,

pregnancy or more usually after birth. In these cases, particularly those to confirm the diagnosis in

caution should be exercised when counseling the the newborn period. If miscarriage, stillbirth, or

family. In those infrequent cases in which the diag- termination occurs, confirmation of diagnosis is

nosis is unequivocally established either because of important for counseling family members about

the familial nature of the disorder or by prenatal recurrence.

radiography, the pediatrician may discuss the 6. Review the currently available treatments and

following issues as appropriate. interventions. This discussion needs to include the

444 HEALTH SUPERVISION FOR CHILDREN WITH ACHONDROPLASIA

AGE - Years

40 _,,a _._ --- 1.

I I I I I I I I

B I 2 3 4 !I 6 7 8 9 IO II I2 I3 I4 l5 I6 I7 I6

AGE -Yews

Fig 1. Height for females with achondroplasia (mean f SD) com-

pared to normal standard curves. Graph is derived from 214

females. (From Horton et a1.4)

I 60-- ACHONDROPLASIA -

HEIGHT 1 1

MO,. H.189

/

160s / / / / / / ./ 1 A/ JI

I 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 9 IO II I2 I3 4 6 I6

AGE - Years

Fig 3. Mean growth velocities (solid line) for males (top) and

females (bottom) with achondroplasia compared to normal

growth velocity curves (dashed lines, 3rd percentile, mean, 97th

percentile). Data are derived from 26 males and 35 females. (From

Horton et a1.4)

small pelvis.Q This surgical procedure usually in-

60 volves general anesthesia because of the mothers

spinal stenosis and the consequent risk associated

i i lb 1!l ,h ,!3 ,b lb 16 ,7 Ii with conduction (spinal/epidural) anesthesia. A

AGE -Years mother affected with achondroplasia may de-

Fig 2. Height for males with achondroplasia (mean + 2SD) com- velop respiratory compromise in the third trimes-

pared to normal standard curves. Graph is derived from 189 ter of pregnancy, so baseline pulmonary function

males. (From Horton et aL4) studies should be done. A pregnancy at risk for

homozygosity should be followed with ultra-

sound measurements at 14, 16, 18, 22, and 32

efficacy, complications, side effects, costs, and weeks of gestation in order to distinguish ho-

other burdens of these treatments. Discuss possi- mozygosity or heterozygosity from normal

ble future treatments and interventions. growth patterns in the the fetus. New DNA diag-

7. Explore the options available to the family for the nostic studies are likely to become available.

management and rearing of the child using a non-

directive approach. In cases of early prenatal di- HEALTH SUPERVISION

agnosis, these may include discussion of preg- FROM BIRTH TO 1 MONTH-NEWBORNS

nancy termination, as well as continuation of Examination

pregnancy and rearing of the affected child at 1. Confirm the diagnosis by radiographic studies

home, foster care, or adoption. When both parents (the diagnosis of approximately 20% of patients

are of disproportionate short stature, the possibil- with achondroplasia has been missed in the past,

ity of double heterozygosity or homozygosity for because it was not suspected on physical exami-

achondroplasia must be assessed. Infants with ho- nation in the newborn period and consequently

mozygous achondroplasia usually are either still- no radiographs were obtained).

born or die shortly after birth. Homozygous 2. Document measurements, including arm span, oc-

achondroplasia can usually be diagnosed prena- cipital frontal circumference (OFC), body length,

tally. and upper to lower body segment ratio; note these

8. If the mother is affected with achondroplasia, a measurements on the achondroplasia special

cesarean section must be performed because of a growth charts at the end of this document. Review

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS 445

ACHONDROPLASlA

HEAD CIRCUMFERENCE

Fmd. N .I45

NONTHS YEARS

AGE

Fig 5. Head circumference for females with achondroplasia com-

pared to normal curves (dashed lines). Data are derived from 145

females. (From Horton et a1.4)

AGE -Years

ACHONDROPLASIA

HEAD CIRCUMFERENCE

60

YEARS- .-

AGE

Fig 6. Head circumference for males with achondroplasia com-

pared to normal curves (dashed lines). Data are derived from 114

females. (From Horton et aL4)

AGE -Years

Fig 4. Upper and lower segment lengths for males (top) and l Growth hormone and other drug therapies are

(bottom) with achondroplasia (mean 0 SD). Data are derived from not effective in increasing stature. Experimental

75 males and 95 females. (From Horton et al?)

work is being done on leg-lengthening proce-

dures at an older age.OJ1

the phenotype with the parents and discuss the l Special achondroplasia growth curves and in-

specific findings with both parents whenever pos- fant development charts have been developed,

sible. and the final expected adult height for persons

3. The OFC should be measured monthly during the with achondroplasia is in the range of about 4

first year. Ultrasound studies of the brain to de- ft.4

termine ventricular size should be considered if 2. Discuss the following possible severe medical

the fontanelle size is unusually large, OFC in- complications:

creases disproportionately, or symptoms of hy- l Unexpected infant death in less than 3% of

drocephalus develop. those affected, usually only in the most severe

cases.12Severe upper airway obstruction in less

Anticipatory Guidance than 5% of those affected, but consider sleep

1. Discuss the specific findings of achondroplasia studies if there appears to be a problem with

with the parents, including: breathing at rest or during sleep, especially if

l Autosomal dominant inheritance. About 75% of developmental landmarks lag.13

cases are new mutations. Germline mosaicism l Restrictive pulmonary disease with or without

(in which some germ cells are derived from a reactive airway disease occurs in less than 5%

normal cell line and some are from a cell line of children with achondroplasia who are

with a mutation) has been reported, but clearly younger than 3 years13;consider pulse oximetry

the risk of recurrence in sporadic cases is far or evaluation for car pulmonale if there are

below 1%. signs of breathing problems.

l Most individuals with achondroplasia have l Development of thoracolumbar kyphosis is as-

normal intelligence and normal life expectancy. sociated with unsupported sitting before there

446 HEALTH SUPERVISION FOR CHILDREN WITH ACHONDROPLASIA

DEVELOPMENTA1 SCREENINGTESTS IN AcHONDROPlASlA

n T

Smile ill

Head Control 113

Pdl cwr ll6

Sat wtth pwpping IY

. 8 ;;;y

hll tq to a stand

z

117

I I I I- I

Standwith support ion

!I

Stand alax l26

Wk with supprt 1~2 ,Y

,.,,

I I I I I I I 1 * E... II

Wk alone 134

w Wingscurds 95

sadMannla/oadda l66

Said 2 WOKI phrase 83

II III I III I- ?,.,t..,^^

s3ii short sentence 80 I ,I 1

I I I I I 1

3 4 5 6 7 3 9lO11l213WPl22022243333 t

%X ci children passing J Fercent d

DENVER dew!qmenta X achondro@stic chddren

screening rests passing the Item

Fig 7. Develoumental screening tests in achondroulasia.

I The 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th centiles are determined by linear interpolation.

(FFom Todoro; et al.?.

is adequate trunk muscle strength.14 6. Discuss the realistic functional problems for af-

l All infants with achondroplasia have a rela- fected individuals.

tively small foramen magnum, but few become 7. Discuss individual resources for support, such as

symptomatic from cord compression at the cer- family, clergy, social workers, and friends.

vicomedullary junction.15 This complication 8. Review the prenatal diagnosis and recurrence

may be manifested by signs and symptoms of a risks for subsequent pregnancies.

high cervical myelopathy, central apnea, or

bothal Rarely, foramen magnum decompres-

sion may be recommended. HEALTH SUPERVISION

l Hydrocephalus may develop during the first 2 FROM 1 MONTH TO 1 YEAR-INFANCY

years, i7 so OFC size should be monitored care-

Examination

fully during this time. If a problem is suspected,

refer the infant to a pediatric neurologist or 1. Assess growth and development in comparison

pediatric neurosurgeon. only to children with achondroplasia.

l The common complication of spinal stenosis 2. Perform physical examination and appropriate

rarely occurs in childhood but manifests in laboratory studies.

older individuals with numbness, weakness, 3. Review head growth.

and altered deep tendon reflexes.18 Children 4. Consider performing a central nervous system

with severe thoracolumbar kyphosis are at ultrasound at 2, 4, or 6 months if the infants

greater risk for this problem. It is for this reason head size increases rapidly in order to evaluate

that unsupported sitting before there is ade- ventricular size. If the size of the OFC or

quate trunk muscle strength is discouraged. ventricles is increasing rapidly, refer the in-

3. Discuss the psychosocial issues related to dispro- fant to a pediatric neurologist or pediatric neu-

portionate short stature. Refer the affected indi- rosurgeon. At 6 to 12 months, consider perform-

vidual, or the parent of an affected individual, to ing additional neuroimaging studies, if appropri-

a support group such as Little People of America ate.

or Human Growth Foundation (see Resources 5. Check motor development and discuss develop-

for New Parents). If parents do not wish to join a ment; note on the milestone charts for achondro-

group, they may want to meet with or talk to plasia. Expect motor delay but not social or cog-

other affected individuals or parents. Remind par- nitive delay.

ents that most individuals with achondroplasia 6. Watch for low thoracic or high lumbar gibbus

lead productive, independent lives. (posterior angulation or kyphosis) associated

4. Discuss with the parents how to tell their family with truncal weakness. It is recommended that

and friends about their childs growth problem. parents avoid carrying a child with achondropla-

5. Supply the parents with educational books and sia in curled-up positions. Certain types of child

pamphlets (see Resources for New Parents). carriers, swingomatics, jolly jumpers, and um-

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS 447

brella strollers tend to increase risk for gibbus. begins, the external rotation of the hips should

Unsupported sitting should be avoided.r2 Par- self-correct to a normal orientation within 6

ents should be instructed to provide back sup- months.

port during the first year of life. 4. Anticipate some bowing of the legs because of

7. External rotation of the hips is frequently present fibular overgrowth at the knees and ankles. If

and usually spontaneously disappears when the bowing leads to an inability to walk, consult a

child begins to bear weight. This finding does not pediatric orthopedist.

require bracing.19 5. Check the childs hips for hip flexion contractures.

8. Check for serous otitis media. Review risk at 6 to Prescribe exercises that may decrease lumbar lor-

12 months. dosis and hip flexion contractures.*9 Check the

9. Arrange sleep studies if any sign of respiratory hips for external rotation. Refer the child to a

compromise or delay in developmental mile- pediatric orthopedist, if necessary.

stones is present. 6. Speech evaluation should be done no later than 2

10. Refer the infant to a pediatric neurologist or pe- years of age. If speech is abnormally delayed con-

diatric neurosurgeon for reflex asymmetry, ex- ductive hearing loss due to chronic serous otitis

treme hypotonia, early hand preference, or ex- media should be excluded.

cessive head growth.5J7 7. Watch for obstructive sleep apnea. Children with

11. Consider magnetic resonance imaging or com- achondroplasia often sweat and snore in association

puted tomography of the foramen magnum re- with sleep. If upper airway obstruction is suspected

gion for a severely hypotonic infant or one who (increased retraction, choking, intermittent breathing,

has signs of cord compression. Magnetic reso- apnea, deep compensatory sighs), further pulmonary

nance imaging should include the base of the evaluation and neurologic examination including so

skull as well as the ventricles and spinal cord matic sensory-evoked responses, sleep studies, and

(Fig S).*O,*l magnetic resonance imaging are needed.

12. Discuss filing for Supplemental Security Income

benefits as appropriate.

Anticipatory Guidance

Anticipatory Guidance 1. Consider adapting the home so the child can

become independent (lower the light switches,

Review the personal support available to the faucets, and supply step stools).

family. 2. Occupational therapy consultation may be

Review contact with support groups. needed.

Observe the emotional status of parents and in- 3. Discuss adapting age-appropriate clothing with

trafamily relationships. snapless, easy-opening fasteners and tuckable

Discuss early intervention services and the impor- loops.

tance of normal socializing experiences with other 4. Discuss adaptation of toys, especially tricycles, to

children. accommodate short limbs.

5. Ask the parents if they have educated their family 5. Discuss adaptation of toilets to allow comfort-

members about achondroplasia; discuss sibling able independent use, with an extended wand

adjustment. for wiping.

6. Review the increased risk of serous otitis media 6. Discuss the use of a stool during sitting so that

because of short eustachian tubes. Indicate that an the childs feet are not hanging. Feet need sup-

ear examination is needed with any upper respi- port while the child is sitting at a desk or in a

ratory tract infection. chair. A cushion behind the childs back may be

7. Avoid infant carriers that curl up the infant. This required for good posture.

does not apply to car safety seats, which should 7. Review weight control and eating habits to avoid

always be used during automobile travel. obesity, which becomes a common problem in

mid to late childhood.22

8. Discuss orthodontic bracing in the future and the

HEALTH SUPERVISION possible need for braces after 5 years of age.

FROM 1 TO 5 YEARS-EARLY CHILDHOOD

9. Encourage the family to develop activities in

Examination which the affected child can take part; avoid

1. Assess the childs growth and development as gymnastics, high diving, acrobatics, and collision

charted on the achondroplasia growth charts. Ob- sports.

tain lower segment measurements once weight 30. Discuss how to talk with the child and other

bearing is established. friends or family members about short stature.

2. Continue to follow head growth. 11. Encourage preschool attendance so that the child

3. Continue to watch for thoracolumbar gibbus and can learn to socialize in an age-appropriate way,

development of lumbar lordosis. Discuss avoiding and work with parents to prepare the teacher

the use of walkers, jumpers, or backpack carriers. and the other children so the child is not given

Any kyphosis present should disappear as the unnecessary special privileges.

child begins to bear weight. Weight-bearing and 12. Discuss toileting at school and special prepara-

walking may occur late; however, they are ex- tions needed by the school because of the childs

pected by 2 years of age. When weight-bearing short stature.

448 HEALTH SUPERVISION FOR CHILDREN WITH ACHONDROPLASIA

, 3 5 7 g 1, 13 15

9.4 5.9 7-9 9.1011.,213-1415*-Normal

Months Years

.A B SAQIlTAL

4.3

4.1

3.9

3.7

3.5

3.3

i

.._

I.1

.o

.7 1

0, 5 5 7 9 11 1s 10 17 19 n

h#onlho Yeuo

Fig 8. CT measurements of the foramen magnum. A, transverse; B, sagittal. Normals are plotted as mean ? ED. Achondroplasia as

individual measurements: the solid circles represent patients with and the open circles patients without evidence of neurologic function,

13. Discourage the child from jumping to decrease Anticipatory Guidance

unnecessary stress on joints, particularly the

joints of the spine.

1. Determine school readiness.

2. Discuss preparation of the school and teacher for

HEALTH SUPERVISION

FROM 5 TO 13 YEARS-LATE CHILDHOOD a child with short stature.

3. Prepare the child for psychosocial situations and

Examination discussing issues. Be sure the child can explain

Assess and review the childs growth and devel- why he or she is short and can ask for help in an

opment and social adaptation. appropriate way. Children with achondroplasia

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS 449

usually are included in the regular education 9. Continue to encourage participation in social ac-

program. tivities and support groups. It is particularly use-

4. Suggest adaptive aids for the school to cope with ful during this age period.

heavy doors, high doorknobs, reaching for the 10. Assist in transition to adult care, with emphasis

blackboard, foot support, and a regular-sized on continued monitoring of the spine.

desk. Also be sure that the child can use the

COMMITTEE ON GENETICS, 1994 TO 1995

restroom independently. Margretta R. Seashore, MD, Chairperson

5. Test hearing regularly each year, checking for Sechin Cho, MD

possible recurrent serous otitis media. Franklin Desposito, MD

6. Check deep tendon reflexes yearly for asymme- Jack Sherman, MD

try or increased reflexes suggesting spinal steno- Rebecca S. Wappner, MD

sis. Miriam G. Wilson, MD

7. Continue to assess history for possible obstruc- LIAISON REPRESENTATIVES

tive sleep apnea. Felix de la Cruz, MD,

8. Review socialization and foster independence. National Institutes of Health

9. Review weight control. The child may need to James W. Hanson, MD,

restrict food intake and eat as little as half as American College of Medical Genetics

Jane Lin-Fu, MD, Health Resources

much as an average-sized child eats. and Services Administration, DHHS

10. Discuss contact with support groups. It is espe- Paul McDonough, MD, American College of

cially valuable at this age. Obstetricians & Gynecologists

11. Obtain an orthopedic evaluation when the child Godfrey Oakley, MD, Centers for

is approximately 5 years of age in order to make Disease Control & Prevention

appropriate treatment plans, if necessary. AAP SECTION LIAISON

12. Emphasize correct posture and encourage the Beth A. Pletcher, MD,

child to consciously decrease lumbar lordosis by Section on Genetics & Birth Defects

tucking the buttocks under. CONSULTANT

13. Develop an activity program with acceptable ac- Judith G. Hall, MD

tivities such as swimming and biking. The child

should avoid gymnastics and contact sports be- RESOURCES FOR NEW PARENTS

cause of the potential for neck or back damage

Human Growth Foundation

due to existing spinal stenosis. 7777 Leesburg Pike

14. Review orthodontic and speech status. Falls Church, VA 22043

703/883-1773 or 800/451-6434

HEALTH SUPERVISION Little People of America

FROM 13 TO 21 YEARS OR OLDER- PO Box 9897

ADOLESCENCE TO EARLY ADULTHOOD Washington, DC 20016

Examination 214/388-9576 or 800/24-DWARF

1. Continue to record parameters. REFERENCES

2. Discuss any signs or symptoms of nerve com-

pression and check deep tendon reflexes, tone, 1. luman achondroplasia. A multidisciplinary approach. Proceedings of

he first international symposium. November 19-21, 1986, Rome, Italy.

and sensory findings, if indicated. hsic Life Sci. 1988;48:1-491

3. Review weight and diet. 2. <ousseau F, Bonaventure J, Legeai-Mallet L, et al. Mutations in the gene

mcoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature.

.994;371:252-254

Anticipatory Guidance 3. jhiang R, Thompson LM, Zhu YZ, et al. Mutations in the transmem-

1. Check on social adaptation. xane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarf-

sm, achondroplasia. Cell. 1994;78:335-342

2. Discuss the diagnosis with the adolescent to be 4. lorton WA, Rotter JI, Rimoin DL, Scott CI, Hall JG. Standard growth

sure that the adolescent has the vocabulary and :urves for achondroplasia. J Pediadiatr.1978;93:435-438

the understanding of the genetic nature of achon- 5. lecht JT, Butler IJ. Neurologic morbidity associated with achondropla-

droplasia. ;ia. J Child Neuuol. 1990;5:84-97

3. Discuss sexuality and reproduction, as well as 6. yeritz RE, Sack GH, Udvarhelyi GB. Thoracolumbosacral laminectomy

n achondroplasia: long-term results in 22 patients. Am J Med Genet.

the necessity for a cesarean section in women for 1987;28:433-444

childbirth.7 7. rodorov AB, Scott CI, Warren AE, Leeper JD. Developmental screening

4. Continue orthodontic evaluation. ,ests in achondroplastic children. Am J Med Genet.

5. Continue weight counseling.22 1981;9:19-23

8. Rogers JG, Perry MA, Rosenberg LA. IQ measurement in children with

6. Encourage the family and affected person to set skeletal dysplasia. Pediatrics. 1979;63:894-897

career and life goals high and appropriate, as for 9. 411anson JE, Hall JG. Obstetrics and gynecologic problems in women

other members of the family. Assist in adapting Nith chondrodystrophies. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:74-78

to an independent life and in obtaining a drivers 10. aley D. Current techniques of limb lengthening. I Pediatr Orthop.

1988;8:73-92

license. (Vocational rehabilitation may pay.) 11. 7imoin DL. Limb lengthening: past, present, and future. Growth Genet

7. Discuss college, vocational planning and train- rnd Hormones. 1991;7:4-6

ing, and other plans following high school. 12. auli RM, Scott CI, Wassman ER, et al. Apnea and sudden unexpected

8. Foster independence. ieath in infants with achondroplasia. J Pediatr. 1984;104:342-348

450 HEALTH SUPERVISION FOR CHILDREN WITH ACHONDROPLASIA

13. Stokes DC, Phillips JA, Leonard CO, et al. Respiratory complications of 18. Hecht JT, Butler IJ, Scott CI. Long-term neurological sequelae in achon-

achondroplasia. [ Pediutr. 1983;102:534-541 droplasia. Eur J Pediatr. 1984;143:58-60

14. Hall JG. Kyphosis in achondroplasia: probably preventable. J Pediatr. 19. Siebens AA, Hungerford DS, Kirby NA. Achondroplasia: effectiveness

1988;112:166-167 of an orthosis in reducing deformity of the spine. Arch Phys Med Rehnbil.

15. Reid CS, Pyeritz RE, Kopits SE, et al. Cervicomedullary compression in 1987;68:384-388

young patients with achondroplasia: value of comprehensive neuro- 20. Hecht JT, Nelson FW, Butler IJ, et al. Computerized tomography of the

logic and respiratory evaluation. J Pediatr. 1987;110:522-530 foramen magnum: achondroplastic values compared to normal stan-

16. Nelson FW, Goldie WD, Hecht JT, Butler IJ, Scott CI. Short-latency dards. Am ] Mcd Gent?. 1985;20:355-360

somatosensory evoked potentials in the management of patients with 21. Hecht JT, Horton WA, Reid CS, Pyeritz RE, Chakraborty R. Growth of

achondroplasia. Neurology. 1984;34:1053-1058 the foramen magnum in achondroplasia. Am ] Med Genet. 1989;32:

17. Steinbok P, Hall JG, Flodmark 0. Hydrocephalus in achondroplasia: the 528-535

possible role of intracranial venous hypertension. 7 Neurosurg. 1989;71: 22. Hecht JT, Hood OJ, Schwartz RJ, et al. Obesity in achondroplasia. Am

42-48 J Med Genet. 1988;31:597-602

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS 451

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Laporan Harian Pasien Puskesmas JatinegaraDocument8 paginiLaporan Harian Pasien Puskesmas JatinegaraanggaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test Bank For Egans Fundamentals of Respiratory Care 9th Edition Robert L WilkinsDocument9 paginiTest Bank For Egans Fundamentals of Respiratory Care 9th Edition Robert L WilkinsPeggy Gebhart100% (28)

- What's in A Name? - The Kew AsylumDocument9 paginiWhat's in A Name? - The Kew AsylumIsabelle FarlieÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Springfields (India) Distilleries" (The Applicant) Is A Registered Partnership FirmDocument8 pagini"Springfields (India) Distilleries" (The Applicant) Is A Registered Partnership FirmACCTLVO 35Încă nu există evaluări

- CV Stratford Sydney IptecDocument7 paginiCV Stratford Sydney Iptecapi-611918048Încă nu există evaluări

- PreliminaryDocument6 paginiPreliminaryPoin Blank123Încă nu există evaluări

- Evidence 1.15.9-Change Log To Demonstrate The Differences Between 2017 and 2021 Edition PDFDocument13 paginiEvidence 1.15.9-Change Log To Demonstrate The Differences Between 2017 and 2021 Edition PDFKhalid ElwakilÎncă nu există evaluări

- EEReview PDFDocument7 paginiEEReview PDFragavendharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Administration of Medication in SchoolsDocument8 paginiAdministration of Medication in SchoolsDavid KefferÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical EpidemiologyDocument38 paginiClinical EpidemiologyLilis Tuslinah100% (1)

- 10 1002@aorn 12696Document7 pagini10 1002@aorn 12696Salim RumraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medication Scanning NRPDocument12 paginiMedication Scanning NRPapi-444018836Încă nu există evaluări

- NOSODESDocument5 paginiNOSODESnamkay_tenzynÎncă nu există evaluări

- NURS FPX 6016 Assessment 2 Quality Improvement Initiative EvaluationDocument5 paginiNURS FPX 6016 Assessment 2 Quality Improvement Initiative EvaluationCarolyn HarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perf. PeritonitisDocument5 paginiPerf. PeritonitisChiriţoiu AnamariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Update On Prenatal Diagnosis and Fetal Surgery ForDocument15 paginiUpdate On Prenatal Diagnosis and Fetal Surgery ForJULIETH ANDREA RUIZ PRIETOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neurophysiological Recordings Improve The Accuracy of 2022 European JournalDocument6 paginiNeurophysiological Recordings Improve The Accuracy of 2022 European Journalcsepulveda10Încă nu există evaluări

- Name: - Score: - Teacher: - DateDocument2 paginiName: - Score: - Teacher: - DatePauline Erika CagampangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eat Healthy for a Healthy MindDocument2 paginiEat Healthy for a Healthy MindEREN CAN BAYRAKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dry Eye Syndrome Keratoconjunctivitis SiccaDocument4 paginiDry Eye Syndrome Keratoconjunctivitis Siccaklinik mandiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Rare Is Heterochromia Iridis?Document19 paginiHow Rare Is Heterochromia Iridis?Bentoys Street100% (1)

- Rundown 2nd Annual Plastic Surgery in Daily PracticeDocument2 paginiRundown 2nd Annual Plastic Surgery in Daily PracticeIzar AzwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Responsibility, Authority and Accountability of EHS/ERT TeamDocument1 paginăResponsibility, Authority and Accountability of EHS/ERT Teamsuraj rawatÎncă nu există evaluări

- OSCE GuideDocument184 paginiOSCE GuideKesavaa VasuthavenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review On Smart Sanitizing Robot With Medicine Transport System For Covid-19Document6 paginiReview On Smart Sanitizing Robot With Medicine Transport System For Covid-19IJRASETPublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tenth Edition: Legally Required BenefitsDocument49 paginiTenth Edition: Legally Required BenefitsJanice YeohÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHE Complete Immunisation Schedule Jan2020 PDFDocument2 paginiPHE Complete Immunisation Schedule Jan2020 PDFJyotirmaya RajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- S. No. City Name Full Address With Contact No.: List of Our ProductsDocument3 paginiS. No. City Name Full Address With Contact No.: List of Our Productsprakashrat1962Încă nu există evaluări

- NABH 5 STD April 2020Document120 paginiNABH 5 STD April 2020kapil100% (7)

- Effectiveness of Communication Board On Level of Satisfaction Over Communication Among Mechanically Venitlated PatientsDocument6 paginiEffectiveness of Communication Board On Level of Satisfaction Over Communication Among Mechanically Venitlated PatientsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări