Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

School Psychology International: Assessment of Coping Styles and Strategies With School-Related Stress

Încărcat de

You YouTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

School Psychology International: Assessment of Coping Styles and Strategies With School-Related Stress

Încărcat de

You YouDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

School Psychology International

http://spi.sagepub.com

Assessment of Coping Styles and Strategies with School-Related Stress

Kazimierz Wrzesniewski and Joanna Chylinska

School Psychology International 2007; 28; 179

DOI: 10.1177/0143034307078096

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://spi.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/28/2/179

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

International School Psychology Association

Additional services and information for School Psychology International can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://spi.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://spi.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations http://spi.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/28/2/179

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Assessment of Coping Styles and Strategies with

School-Related Stress

KAZIMIERZ WRZESNIEWSKI and JOANNA CHYLINSKA

Faculty of Psychology, Warsaw University, Poland

ABSTRACT A review of the relevant literature indicates a lack of

measurement techniques for coping styles and strategies with school-

related stress. This study presents the procedure of constructing The

Coping with School-related Stress Questionnaire (CSSQ), which makes

it possible to investigate dispositional as well as situational aspects of

coping. Theoretical assumptions are based on the interactive model of

coping with stress, which distinguishes styles and strategies of coping

with school-related stress. CSSQ consists of 2 forms: Form A is

designed to examine coping styles; Form B is designed to examine

strategies of coping with school-related stress. On the basis of several

factorial analyses three scales of the CSSQ have been distinguished:

task, emotion and avoidance coping. The score is assessed for each

scale separately. The psychometric coefficients of CSSQ are satisfac-

tory. CSSQ is designed for adolescents, aged 1516. Further research

concerning its diagnostic qualities among different age groups needs to

be conducted.

KEY WORDS: assessment of coping; coping strategies; coping styles;

interactive model of coping; school-related stress

Introduction

The interactive paradigm, encompassing both situational and disposi-

tional factors has become increasingly popular and has proved to be

useful in research (see Carver et al., 1989; Endler and Parker, 1999;

Wrzesniewski, 1996; Wrzesniewski and W!odarczyk, 2001; Zeidner,

1995). This approach, however, encounters difficulties when empirical

verification of both groups of variables is required. One of the questions

to answer is the selection of appropriate measurement techniques.

Please address correspondence to: Dr Kazimierz Wrzesniewski, Warsaw

University, Faculty of Psychology, 00183 Warsaw, ul. Stawki 517, Poland.

Email: jchylinska@engram.psych.uw.edu.pl

School Psychology International Copyright 2007 SAGE Publications (Los

Angeles, London, New Delhi and Singapore), Vol. 28(2): 179194.

DOI: 10.1177/0143034307078096

179

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

Usually, authors use separate assessment devices for measuring differ-

ent categories of coping with stress. Subsequently, the interpretation of

the results becomes rather difficult. The case is especially complex

when we want to conduct research on coping with stress among chil-

dren and adolescents as measures need to take account of the age of the

participants.

It has been shown that the number of strategies applied in a stress-

ful situation increases with age or with experience in that kind of

situation (Blount et al., 1991). Moreover, the type of chosen response

also changes, as is demonstrated in a number of studies documenting

differences in the use of certain coping strategies depending on the age

of participants. Ryan (1989) found that the strategy used most often by

8-year-olds was social support, but by 9-year-olds, verbal aggression

and avoidance. Eleven-year-olds displayed most physical activity and

12-year-olds preferred relaxation and cognitive activities. Differences

were also reported among adolescents aged 1318 (Groer et al., 1992).

Moreover, there is some evidence that, when coping with uncontrol-

lable events, youngsters tend to use emotion-focused coping, while

problem-oriented responses targeting modification of the situation

are less in evidence. Age differences in applied coping strategies are

apparent regardless of the type of assessment measure used (see also

Frynberg and Lewis, 1991; Ryan, 1989; Seiffke-Krenke, 1990; 1993).

Some coping strategies are employed in relation to environmental

and personal factors. Age of investigated children and adolescents may

play a crucial role in distinguishing the importance of these factors.

The results show that 1519 year-old adolescents use consistent

patterns of coping strategies, but this consistency remains only within

a certain domain. In other words, young people react differently when

their problems pertain to school and when the stressor is connected

with parents (Seiffke-Krenke, 1990, 1993). The study of Boekaerts

(1996) showed that one type of strategy dominates when school

stressors are considered and another when we take into account inter-

personal stressors. Additionally, the type of events that trigger

stress, changes with age. Amongst children and adolescents up to

the age of 14, the most salient role play stressors concern the family

environment, while older groups name school problems and peer

stressors as the most relevant (Compas et al., 1989).

The importance of school-related stress is difficult to overestimate.

Lohman and Jarvis (2000) reported that the most prevalent cause

of stress named by adolescents was problems related to school, as

reported by 100 percent of girls and 96 percent of boys. Also, some

researchers have hypothesized that difficulties in coping with school-

related stress may be a first step toward development of chronic fatigue

syndrome (Kulik and Szewczyk, 2003). A growing body of studies

180

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Wrzesniewski and Chylinska: Coping Styles and Strategies

concerning examination stress, which might be also considered as

school-related stress, adds to the importance of this subject (Schwarzer

and Buchwald, 2003). For these reasons it was considered worthwile to

prepare a measuring technique designed specifically for this distinctly

important area of adolescent life.

Existing questionnaires that measure coping with stress in children

and adolescents do not take account of all the conditions mentioned

above. Authors of stress assessment devices often do not specify what

kind of coping they intend to measure: a stable disposition in the

form of coping with stress or responses of a person in a certain type of

stressful encounter (Boekaerts, 1996). Another quite common short-

coming, of questionnaires for adults as well, is that the instruments are

not derived from a theoretical framework (Schwarzer and Schwarzer,

1996; Zeidner, 1995).

There are quite a few measures which assess coping strategies

among adolescents, however, it is difficult to identify even one which is

designed to assess coping with school-related stress directly. Usually,

scales tend to contain items regarding school problems, but the score is

considered to indicate strategies of coping with stress in general.

A variety of available techniques is presented in Boekaerts (1996)

work. She discusses three groups of techniques: (1) questionnaires list-

ing stressful events or daily hassles; (2) observation and case studies

and (3) coping strategies inventories. It seems, that the second group

could be extended also by interviews.

Since there is an available literature discussing the subject, we limit

the presentation of various techniques to single examples from each

group, with particular attention given to the problem of including the

school-related stress and coping aspects.

(1) The first group of instruments mentioned above does not actually

pertain to coping, but deals with an amount of stress experienced by

adolescents. As has been mentioned, there is no scale which considers

school-related stress only. Authors wishing to conduct research usually

have to rely on single items derived from more general lists. An exam-

ple of this approach is the study of Torsheim et al. (2003) who used two

subscales in their research (one derived from Health Behaviour in

School-aged Children, consisting of three items and a two-item High

Academic Expectations scale (Samdal et al., 1998).

(2) In the study of Seiffge-Krenke et al. (2001) The Coping Process

Interview (Seiffge-Krenke, 1993) was used to evaluate coping with

school-related stress, understood in terms of getting a bad grade. The

interview consists of seven open questions pertaining to information in

the following domains: (i) the definition of the situation a description

of the stressful event in detail; (ii) the context in which the event

occurred; (iii) the subjective interpretation of the causes; (iv) the

181

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

appraisal of the event as threatening, challenging or loss; (v) the

coping process including thoughts, feelings, and actions to deal with

the stressor; (vi) the evaluation of intended and achieved effects and

(vii) the reappraisal. The interview covers a wide variety of issues,

moreover, it makes it possible to investigate school-related stress.

However, it should be conducted individually and is therefore rather

time consuming.

(3) The method elaborated by Dise-Lewis (1988) Life Events and

Coping Inventory (LECI) is a combination of a checklist of 125 poten-

tially stressful life events and 49 coping strategies. On the base of a

factor analysis five empirical scales have been formed: Aggression,

Stress recognition, Distraction, Self-destruction and Endurance. The

questionnaire is appropriate for 1114 years old. Participants are

asked to select events that they have experienced within the recent

year, rate their stressfulness and identify appropriate coping strate-

gies. However, the questionnaire does not rely on a theory as the

process of construction was empirical. Furthermore, it does not address

the problems of school-related coping directly.

The facts reported above were the inspiration for the construction of

a questionnaire for adolescents, which would be free of the identified

weaknesses. Preceeding work on the stress assessment tool, the follow-

ing rules were established. First of all, the questionnaire should be

well settled in a specific psychological theory. Secondly, it had to cover

both facets of coping and, as a result, assessment of both dispositional

and situational factors should be possible. Thirdly, it was required to

clearly state the category of stressful situations and age of people it

was designed for. Fourthly, it should be characterized by satisfactory

reliability and validity coefficients.

Theoretical assumptions of the Coping with School-Related Stress

Questionnaire (CSSQ) are discussed below. Further we briefly outline

the procedure of preparing the questionnaire, studies aimed at identi-

fying diagnostic items, as well as reliability and validity research.

Finally, we present the questionnaires psychometric properties and

possible ways of application.

Theoretical bases of the Coping with School-related Stress

Questionnaire (CSSQ)

In the well known theory of Lazarus and Folkman, coping with stress is

understood in terms of a transactional process (Folkman et al., 1986;

Lazarus, 1980, 1993; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984, 1987). That implies

that there is not only an interaction between a person and an environ-

ment, but there are also simultaneous changes within the person and

the environment over time. This approach triggers several theoretical

182

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Wrzesniewski and Chylinska: Coping Styles and Strategies

and, in particular, methodological difficulties (Wrzesniewski, 1996;

Wrzesniewski and W!odarczyk, 2001). The most important one regards

empirical verification of such a complex and dynamic process. Measur-

ing the phenomenon, when all the variables change as well as

interactions between them, is very difficult. Troubles start from the

very beginning when a decision about the aspect of coping which is

going to be assessed is required, then, difficulties with identification of

appropriate indicators emerge and finally, acquired results might be

difficult to interpret. For this reason an interactional model rather

than the transactional approach is proposed. In this model coping

styles, strategies and coping processes are distinguished (Wrzesniews-

ki, 1996; 2001; Wrzesniewski and Wlodarczyk, 2001). Coping style is

defined as a stable personality disposition to cope with different stress-

ful situations in a given way. This disposition does not depend on any

kind of a stressful encounter, as it is an attribute of the person. Never-

theless, that does not mean that it influences coping with all stressful

situations in the same way, as coping with a particular situation

depends on several other factors. Coping strategies are cognitive

and behavioural efforts people make to manage a specific stressful

situation. Truancy during a test or instrumental aggression after a

quarrel with a colleague are examples of a coping strategies in school

environment The coping process is a sequence of altering strategies

accompanying changes within the situation (Wrzesniewski, 1996;

Wrzesniewski and W!odarczyk, 2001).

In their conception, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) ascribe a funda-

mental part in coping with stress to stress appraisal. A similar

assumption is made in the interactional model. In the proposed inter-

actional model two kind of stress appraisal were distinguished:

dispositional and situational. Dispositional stress appraisal is a stable,

personality based tendency to appraise different stressful situations in

a similar way. This disposition determines individual differences in

perceiving and interpreting occurring events. This variable allows us to

explain why different people perceive the same situation differently

and why the same person perceives different situations in similar

categories (Wlodarczyk, 1999; Wrzesniewski and Wlodarczyk, 2001).

The distinction between dispositional and situational stress

appraisal is coherent with the previously given distinction between

coping styles and coping strategies. It corresponds very well with the

commonly known conception of trait-state anxiety by Spielberger

(Spielberger et al., 1970).

Strategies of coping with school-related stress depend directly and

indirectly on several factors. As well as the coping style and situational

appraisal mentioned earlier, an equally important part is played by

current psycho-physical conditions of a person and their family

183

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

School-related Gender,

Present life

stressful personality and

situation

situation other stable

individual traits

Current Situational Dispositional

Psycho-physical stress stress

state appraisal appraisal

COPING COPING

STRATEGY STYLE

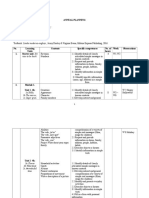

Figure 1 Interactive model of coping with school-related stress

situation (especially noteworthy is the nature of their relationship with

their parents, relationship between parents and economic status of the

family). An applied strategy is also influenced by gender, personality

(e.g. self-efficacy, level of need of achievement, level of optimism) and

other stable characteristics of an individual, such as temperament. The

directions of the relationships between components of the model as

illustrated in Figure 1 are hypothetical and require further empirical

verification. The theoretical assumptions, briefly discussed here,

compose a framework for the Coping with School-related Stress

Questionnaire.

Preliminary version of the Coping with School-related Stress

Questionnaire (CSSQ)

When preparing to construct the questionnaire, a rational-empirical

approach was chosen. Based on the specific theoretical framework,

the preliminary version of the questionnaire was prepared and then

administered to a group of participants. Factor analysis was performed;

empirically derived factors were then compared with theoretical scales.

Referring to the work of Endler and Parker (1994, 1999), three types

of coping with stress were defined: task-oriented, emotion-oriented and

avoidance-oriented.

In the first type of coping an individual engages in activities or

184

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Wrzesniewski and Chylinska: Coping Styles and Strategies

behavioural reconstruction of the situation. In the second type of

coping an individual focuses on the self and his/her own emotional

experiences and at the same time acts so as to reduce the emotional

tension related to the stressful situation. The third type of coping

demonstrates the tendency to avoid thinking, feeling and experiencing

the stressful situation by engaging in substitute activities.

For each of three categories 30 items were prepared and rated by an

independent, competent judge. The task of a judge was to give each

item a rating, ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 meaning that the item did not

reflect the category at all; 2 that the item was poorly reflected; 3 that

the item was rather reflected; 4 that the item was well reflected and 5

that the item very well reflected the category. Seventy-six items match-

ing the category well or very well were included in the preliminary

version. In this set, there were 21 items dealing with task-oriented

coping, 37 dealing with emotion-oriented coping and 18 dealing with

avoidance-oriented coping.

This preliminary questionnaire was administered to 293 high-school

students, 114 boys and 179 girls, aged 1516. The task of each partici-

pant was to recall a stressful situation that had happened recently at

school and then, to mark on a four-point Liekert scale whether a par-

ticular response occurred due to the recalled situation. A statement

was included into a factor when a factor loading was 0.35 or more

and had simultaneous negative or low loadings of the remaining two

factors. Obtained empirical scales were compared with rational scales.

Only the items consistent on both the theoretical and empirical level

were included in the final questionnaire. On the basis of this selection

42 items were acquired, among which 15 were task-oriented, 13

emotion-oriented and 14 avoidance-oriented (Zalewska, 1994).1

Since a few empirical items were inconsistent with theoretical

scales, and also since 34 items were nondiagnostic, work on the final

version of the CSSQ was continued. Another argument in favour of

further elaboration of the CSSQ was the wish to construct an instru-

ment which could be used to diagnose both styles and strategies of

coping with school-related stress.

Coping style and coping strategies questionnaire

By this means, two versions of the questionnaire, A and B, were pre-

pared. The major difference between the two is in the instruction. Form

A is designed to assess coping styles. Pupils are asked to respond by

indicating how they usually behave in different school-related stressful

situations. Form B is concerned with coping strategies. Participants

are asked to mark answers with reference to a specific stressful

encounter related to school. The items in the two questionnaires

185

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

Table 1 Factorial analysis of the CSSQ, Form A and Form B for

girls, n = 393

Form A Form B

Item Factor I Loadings Item Factor I Loadings

Factor 1 17 0.708 17 0.695

28 0.674 3 0.683

3 0.666 28 0.670

2 0.624 37 0.653

22 0.619 12 0.634

25 0.619 31 0.628

31 0.618 2 0.612

37 0.573 25 0.610

12 0.573 22 0.582

6 0.506 34 0.545

34 0.506 6 0.524

32 n.s.

Eigenvalue 4.557 4.785

% of Explained Variance 13.8 14.5

Form A Form B

Item Factor II Loadings Item Factor II Loadings

Factor II 33 0.662 10 0.657

14 0.603 29 0.648

16 0.581 20 0.589

1 0.559 39 n.s.

42 0.552 13 0.527

24 0.541 35 0.476

36 0.536 38 0.465

11 0.392 7 0.439

27 0.366 23 0.432

5 n.s. 4 0.424

Eigenvalue 3.434 3.361

% of Explained Variance 10.4 10.2

Form A Form B

Item Factor III Loadings Item Factor III Loadings

Factor III 10 0.654 33 0.712

29 0.640 14 0.588

13 0.561 36 0.586

35 0.524 24 0.546

20 0.511 1 0.502

23 0.479 21 0.474

7 0.471 16 0.469

39 n.s. 27 0.460

32 0.388 42 0.429

38 n.s. 11 0.353

4 n.s. 5 n.s.

21 n.s.

Eigenvalue 2.561 2.958

% of Explained Variance 7.8 9.0

186

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Wrzesniewski and Chylinska: Coping Styles and Strategies

also differ with respect to grammatical form. Both forms of the CSSQ

consist of 42 items. New items were substituted for the ones which did

not conform with the theoretical scales. The questionnaires, thus

prepared, were administered to 696 1st-grade high-school pupils (393

girls and 303 boys), aged 1516 from five secondary schools in Warsaw.

In between the completion of the first and the second questionnaire

pupils were given the Marlow-Crown Social Desirability Scale and the

BWZ Questionnaire measuring Type A behaviour pattern (these data

were analysed elsewhere). Half of the participants filled in Form A of

the CSSQ first and Form B second, the other half filled in the question-

naires in the opposite order.

The responses were factor-analysed (Varimax rotation), with a limi-

tation to three factors (three types of coping), separately for boys and

girls. As in the previous studies, the criteria of inclusion in a factor

were a factor loading of 0.35 or more and negative or low loadings on

the remaining factors.

Table 1 provides a comparison of positive loadings for girls on Forms

A and B on each of the three factors. It can be seen that a considerable

degree of concordance occurs with the exception of items 4, 5, 11, 21, 35.

A similar comparison for boys of factor loadings on Forms A and B is

shown in Table 2. Here a slightly different strength of effect is shown

on factors two and three. The slightly weaker loadings here are seen on

items 5, 11, 21, 32. Table 3 provides the factor loadings for the whole

group taken together on Forms A and B.

The next step was to compare empirically derived scales with theo-

retical ones. We acquired full concordance between empirical Factor

one and a scale theoretically defined as Task-oriented coping. Nine out

of ten items on Factor two were consistent with the theoretical scale

defined as emotion-orieted coping.

The final three scales of the CSSQ are presented in Appendix 1. Each

scale is scored separately by summing up the reponse weights accord-

ing to the scoring key.

Conducted correlation analysis confirm also considerable independ-

ence of the scales.

Correlation between scales coefficients obtained separately for girls

and boys, in Form A and Form B are low and range from 0.017 to

0.286.

Correlational analyses were also conducted for the purpose of the

assessment of the possible social desirability bias. The obtained coeffi-

cients between three scales of the CSSQ and the Marlow-Crown Social

Desirability Scale range from 0.06 to 0.20. These findings confirm

that the responses in both forms of the CSSQ are not biased by social

desirability.

187

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

Table 2 Factorial analysis of the CSSQ, Form A and Form B for

boys, n = 303

Form A Form B

Item Factor I Loadings Item Factor I Loadings

Factor 1 28 0.762 31 0.742

6 0.748 2 0.705

2 0.745 28 0.695

17 0.741 12 0.693

12 0.719 25 0.688

25 0.692 22 0.662

22 0.679 17 0.653

31 0.630 37 0.651

37 0.628 6 0.606

34 0.597 34 0.503

3 0.566 3 0.364

Eigenvalue 5.975 5.461

% of Explained Variance 18.1 16.5

Form A Form B

Item Factor II Loadings Item Factor II Loadings

Factor II 14 0.704 33 0.628

33 0.637 36 0.615

36 0.615 5 0.583

24 0.609 14 0.582

16 0.581 16 0.530

42 0.579 24 0.529

5 0.543 27 0.525

27 0.506 1 0.474

1 0.449 42 0.463

21 0.375 11 n.s.

11 n.s. 21 n.s.

Eigenvalue 3.887 3.477

% of Explained Variance 11.8 10.5

Form A Form B

Item Factor III Loadings Item Factor III Loadings

Factor III 39 0.694 29 0.653

29 0.669 39 0.634

23 0.646 10 0.567

4 0.604 7 0.552

10 0.591 20 0.518

20 0.500 4 0.511

13 0.444 13 0.497

38 0.383 35 0.456

7 n.s. 38 0.406

32 n.s. 23 0.397

35 n.s. 32 n.s.

Eigenvalue 2.788 2.747

% of Explained Variance 8.4 8.3

188

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Wrzesniewski and Chylinska: Coping Styles and Strategies

Table 3 Factorial analysis of the CSSQ, Form A and Form B, for the

entire group, n = 696

Form A Form B

Item Factor I Loadings Item Factor I Loadings

Factor 1 17 0.720 28 0.684

28 0.703 17 0.681

2 0.676 31 0.678

25 0.649 12 0.660

22 0.636 2 0.655

12 0.632 37 0.650

3 0.628 25 0.644

31 0.621 22 0.611

6 0.614 3 0.566

37 0.594 6 0.558

34 0.545 34 0.522

32 n.s.

Eigenvalue 5.110 5.066

% of Explained Variance 15.5 15.4

Form A Form B

Item Factor II Loadings Item Factor II Loadings

Factor II 29 0.732 29 0.725

39 0.642 39 0.680

23 0.633 10 0.621

10 0.613 20 0.558

20 0.550 23 0.539

4 0.525 38 0.504

13 0.488 13 0.486

35 0.453 35 0.476

38 0.417 4 0.470

7 0.372 7 0.447

32 n.s.

Eigenvalue 3.589 3.332

% of Explained Variance 10.9 10.1

Form A Form B

Item Factor III Loadings Item Factor III Loadings

Factor III 14 0.659 33 0.658

33 0.622 14 0.597

24 0.590 36 0.565

16 0.577 24 0.544

42 0.555 27 0.504

36 0.530 16 0.494

1 0.509 1 0.486

27 0.452 5 0.445

5 0.413 42 0.440

11 0.345 21 0.399

21 n.s. 11 0.365

Eigenvalue 2.683 2.983

% of Explained Variance 8.1 8.9

189

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

Table 4

Gender CSSQ. Form A CSSQ. Form B

Task Emotion Avoidance Task Emotion Avoidance

Girls (N=393) 0.856 0.790 0.742 0.843 0.775 0.725

Boys (N=303) 0.863 0.783 0.737 0.840 0.757 0.704

Reliability and validity

The reliability of CSSQ was calculated by the internal consistency co-

efficient. Values of the Cronbach alpha for CSSQ Forms A and B are

presented in Table 4.

The theoretical validity of the CSSQ was assessed by comparing the

items which made up the empirical scales (following factor analyses)

with the theoretical scale items. As already mentioned, each of the

items producing the respective empirical scales was also included in

the theoretical scales. The procedure used in the study corresponds

with the method of distinguishing coping styles by Endler and Parker.

Present findings show that percent of explained variance changes

depending on the aspect of coping as well as on the examined sub-

sample. Three factors of Form A in girls account for 32 percent of

explained variance, for 38.30 percent in boys and for 34.50 percent in

the entire group. Analogical results for Form B are 33.70 percent for

girls, 35.30 percent for boys and 34.40 percent for the entire group.

Data presented in Tables 1 to 6 are very consistent, as the same factor

structure was revealed in all the analyses. Additionally, independence

of the three scales of the CSSQ was confirmed in the study, which is in

full concordance with theoretical assumptions.

Discussion and conclusions

The elaborated Coping with School-related Stress Questionnaire is

based on the interactive paradigm of coping with stress and is designed

for adolescents, aged 1516. One of the unquestionable strengths of the

present instrument is its settlement in the psychological theory. The

construction of many coping inventories targeting children and youth

was mainly empirical, and not well balanced with rational procedures,

while in case of the CSSQ the scales emerged as a result of both types of

steps. What is noteworthy is, unlike other coping inventories, the

CSSQ addresses school-stress directly and is designed for a specific age

group.

The presented model encompasses situational and dispositional

factors. Subsequently, the CSSQ consists of two forms: A and B. Form

190

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Wrzesniewski and Chylinska: Coping Styles and Strategies

A is for coping styles and Form B is used to assess strategies employed

Therefore, it meets the standards of covering both facets of coping.

Both forms consist of the same 42 items, the difference is in the instruc-

tion given to participants. In Form A, a person is asked to respond by

indicating how he or she usually behaves in various stressful situations

at school. In Form B answers pertain to a specific stressful encounter

given in the instruction. A subject responds to each item on the

four-pont Liekert scale. Thirty out of 42 items are diagnostic: 11 for

task-oriented coping, nine for emotion-oriented coping and ten for

avoidance-oriented coping. The remaining 12 items are buffers. The

score is assessed for each scale separately, in Form A as well as in

Form B.

As a result of several factorial analyses, three scales of the CSSQ

were distinguished: task, emotion and avoidance coping. Therefore, the

technique is compatible with the leading coping instruments. Although

a stable factor structure was obtained in the study, only moderate per-

cents of explained variance were acquired. These findings give support

for the interactional model of coping, where specific aspects of coping

are strongly related to various factors named in the model, however,

further research on validity of the measure is necessary.

Another limitation of the study pertains to the sample of partici-

pants, who came from Warsaw secondary schools. In order to generalize

conclusions it would be necessary to perform wider randomized trials.

In general, it has to be concluded that the presented instrument may

be successfully applied in the school context for measuring coping

among adolescents. It is designed specifically for this age group and

relates to school stress understood in a broad sense. These qualities

make the CSSQ a valuable measurement technique. Further research

concerning its diagnostic qualities among different age groups should

be conducted, which is an especially vital issue for practicing school

psychologists, who wish to use this method for diagnostic purposes.

Until the normative data are gathered, the CSSQ should be applied as

a research technique only.

Notes

Support for this work was partly provided by the Department of Psychology,

Warsaw University, grant number 1695/15.

1. The data were partly collected within the Master thesis of H. Zalewska.

191

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

References

Boekaerts, M. (1996) Coping with Stress in Childhood and Adolescence, in M.

Zeidner and N. S. Endler (eds) Handbook of Coping, pp.45284. New York:

John Wiley and Sons.

Blount, R. L., Landolf-Fritsche, B., Powers, S.W. and Sturges, J.W. (1991)

Differences Between High and Low Coping Children and Between Parent

and Staff Behaviours During Painful Medical Procedures, Journal of

Pediatric Psychology 16: 795809.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. and Weintraub, J. K. (1989) Assessing Coping

Strategies: A Theoretically Based Approach, Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology 56: 267283.

Compas, B. E., Phares, V. and Ledoux, N. (1989) Stress and Coping Preventive

Interventions for Children and Young Adolescents, in L. A. Bond and B. E.

Compas (eds) Primary Preventions and Promotion in the Schools, pp. 319

41. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Endler, N. S. and Parker, J. D. A. (1994) Assessment of Multidimensional

Coping: Task, Emotion and Avoidance Strategies, Psychological Assessment

6: 50-60.

Endler, N. S. and Parker, J. D. A. (1999) Coping Inventory for Stressful Situa-

tions (CISS): Manual (Revised Edition). Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R., Dunkel-Schetter, C., De Longis, A. and Gruben, R. J.

(1986) Dynamics of Stressful Encounters: Cognitive Appraisal, Coping and

Encounter Outcomes, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50:

9921003.

Frydenberg, E. and Lewis, R. (1991) Adolescent Coping: The Different Ways in

Which Boys and Girls Cope, Journal of Adolescence 14: 11933.

Gror, M. W., Thomas, S. P. and Shoffner, D. (1992) Adolescent Stress and

Coping: A Longitudinal Study, Research in Nursing and Health 15: 20917.

Lohman, B. J. and Jarvis, P. A. (2000) Adolescents Stressors, Coping Strate-

gies, and Psychological Health Studied in The Family Context, Journal of

Youth and Adolescents 29: 1543.

Kulik, A. and Szewczyk, L. (2003) Radzenie sobie ze stresem u nastolatkw z

.

rznym poziomem zmeczenia [Coping Among Adolescents with Different

Levels of Fatigue], in Z. Juczynski and N. Oginska-Bulik (eds) Zasoby

osobiste i spo eczne sprzyjaja ce zdrowiu jednostki, pp. 17695. "dz,:

Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu "dzkiego.

Lazarus, R. S. (1980) The Stress and Coping Paradigm, in L. A. Bond and J. C.

Rosen (eds) Competence and Coping During Adulthood, pp. 2874. Hanover:

University Press of New England.

Lazarus, R. S. (1993) Coping Theory and Research: Past, Present and Future,

Psychosomatic Medicine 55: 23447.

Lazarus, R. S. and Folkman, S. (1984) Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York:

Springer.

Lazarus, R. S. and Folkman, S. (1987) Transactional Theory and Research on

Emotions and Coping, European Journal of Personality 1: 14169.

Ryan, N. M. (1989) Stress-Coping Strategies Identified From School Age Chil-

drens Perspective, Research in Nursing and Health 12: 11122.

Samdal, O., Nutbeam, D. Wold, B. and Lkannas L. (1998) Achieving Health

192

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Wrzesniewski and Chylinska: Coping Styles and Strategies

and Educational Goals Through Schools A Study of the Importance of

the School Climate and the Students Satisfaction with School, Health

Education Research 13(3): 38397.

Schwarzer, C. and Buchwald, P. (2003) Introduction. Examination Stress:

Measurement and Coping, Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 16(3): 24749.

Schwarzer, R. and Schwarzer, C. (1996) A Critical Survey of Coping Instru-

ments, in M. Zeidner and N. S. Endler (eds) Handbook of Coping, pp. 107

32. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Seiffke-Krenke, I.(1990) Developmental Processes in Self-Concept and Coping

Behaviour, in H. Bosma and S. Jackson (eds) Coping and Self-Concept in

Adolescence, pp. 5168. Berlin: Springer.

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (1993) Coping Behavior in Normal and Clinical Samples.

More Similarities Than Differences?, Journal of Adolescence 16: 285303.

Seiffge-Krenke, I.,Weidemann, S., Fentner, S., Aegenheister, N. and Poeblau,

M. (2001) Coping with School-Related Stress and Family Stress in Healthy

and Clinically Referred Adolescents, European Psychologist 6(2): 12332.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorush, R. L. and Lushene, R. E. (1970) Manual for the

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists

Press.

Torsheim, T., Aaroe, L. and Wold, B. (2003) School-Related Stress, Social

Support, and Distress: Prospective Analysis of Reciprocal and Multilevel

Relationships, Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 44(2): 15360.

Wlodarczyk D. (1999) Rola i miejsce oceny poznawczej w radzeniu sobie ze

stresem [The Role of Cognitive Appraisal in Coping With Stress], Nowiny

Psychologiczne 4: 5773.

Wrzesniewski, K. (1996) Style a strategie radzenia sobie ze stresem. Problemy

pomiaru [Coping Styles and Strategies. Measurement Issues], in I. Heszen-

Niejodek and Z. Ratajczak (eds) Cz owiek w sytuacji stresu. Problemy

teoretyczne i metodologiczne, pp. 4464. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwer-

sytetu Sla skiego.

Wrzesniewski, K. and W!odarczyk, D. (2001) The Role of Cognitive Appraisal

in Coping With Stress After Myocardial Infraction: Selected Theoretical and

Methodological Issues, Polish Psychological Bulletin 32: 10914.

Zalewska, H. (1994) Strategie radzenia sobie ze stresem szkolnym stosowane

przez uczniw pierwszych klas licew panstwowych i spo!ecznych [Coping

Strategies With School-Related Stress Among First Year High-School

Pupils Attending Public and Private Schools], unpublished masters thesis.

Psychology Department, Warsaw University, Poland.

Zeidner, M. (1995) Adaptive Coping With Test Situations: A Review of the

Literature, Educational Psychologist 30(3): 12333.

193

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

School Psychology International (2007), Vol. 28(2)

Appendix 1

Item

number Task-oriented coping

2 I try to anticipate and prevent possible further troubles

3 I attempt various forms of action to solve the problem

6 I seek information which could help me to solve my problem

12 I try to analyse my position and find the cause of my problem

17 I try to get rid of my problems systematically and gradually

22 I concentrate completely on solving the problem

25 Before taking any steps I consider what choice to make

28 I try to act methodically and rationally

31 I organize my life and what I am to do

34 I try to develop my skills and potentials

37 I change these elements in my behaviour which may have con-

tributed to the problem

Emotion-oriented coping

4 I complain to someone in the family

7 I think of times when I felt better

10 I feel sorry for myself

13 I imagine how different things could be

20 I ask various people to give me their opinion about what has

happened to me

23 I relieve myself by crying

29 I complain to friends

32 I accuse myself of procrastinating

35 I am mad and yell at people

38 I ask a classmate for help

39 I talk with friends about what I experience

Avoidance-oriented coping

1 I listen to music

5 I watch TV

11 I sleep more

14 I go to the cinema

16 I go shopping, buy myself something I like

21 I miss classes

24 I watch films on the video

27 I drink beer, wine or liquor

33 I socialize

36 I spend time with my sweetheart

42 I joke and retain my sense of humor

194

Downloaded from http://spi.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Summary - Granovetter (1985) Economic Action and Social StructureDocument2 paginiSummary - Granovetter (1985) Economic Action and Social StructureSimon Fiala100% (11)

- Cel 2103 - SCL Worksheet Week 8Document5 paginiCel 2103 - SCL Worksheet Week 8ms zaza100% (1)

- Review of Related Literatures and Studies LLLLDocument17 paginiReview of Related Literatures and Studies LLLLreynald salva95% (19)

- Academic Stress and Coping StrategiesDocument11 paginiAcademic Stress and Coping StrategiesParty PeopleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature Rx: Improving College-Student Mental HealthDe la EverandNature Rx: Improving College-Student Mental HealthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drama Therapy Exercises PDFDocument27 paginiDrama Therapy Exercises PDFrosenroseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stress Research PaperDocument8 paginiStress Research Papergz45tyye100% (1)

- Document 10Document7 paginiDocument 10hailleybrookeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Causes of Academic Stress On Students by HassanDocument16 paginiCauses of Academic Stress On Students by HassanM Hassan Tunio100% (1)

- Article1379492114 - Kumar and Bhukar PDFDocument7 paginiArticle1379492114 - Kumar and Bhukar PDFtathokozasalimuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Does Stress Affect Academic Performance?Document7 paginiDoes Stress Affect Academic Performance?Jao Austin BondocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stress, Sex Differences, and Coping Strategies Among College StudentsDocument13 paginiStress, Sex Differences, and Coping Strategies Among College StudentsSamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5stress Can Be Characterized As ''A Condition of Mental or Enthusiastic Strain orDocument5 pagini5stress Can Be Characterized As ''A Condition of Mental or Enthusiastic Strain orAravindhan AnbalaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Long Proposal Template For The 2009 NCFR Annual Conference: ProcedureDocument6 paginiLong Proposal Template For The 2009 NCFR Annual Conference: ProcedureHaiping WangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stressors Among Grade 12 HUMSS Students On Pandemic LearningDocument21 paginiStressors Among Grade 12 HUMSS Students On Pandemic LearningEllaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Content ServerDocument17 paginiContent ServerDorin TriffÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dealing With StressDocument19 paginiDealing With StressFatimah AlzayerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research and Development: Stress: Causes and EffectDocument9 paginiResearch and Development: Stress: Causes and EffectKuan LingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 5 RESEARCH HUMSS 11 2PDocument36 paginiGroup 5 RESEARCH HUMSS 11 2PMich Elbir100% (1)

- Social Anxiety and The School Environment of AdolescentsDocument31 paginiSocial Anxiety and The School Environment of Adolescentskahfi HizbullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Role For Social Psychology Instruction in Reducing Bias and ConflictDocument11 paginiA Role For Social Psychology Instruction in Reducing Bias and ConflictsashasalinyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Academic Stress in The Final Years of School: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument30 paginiAcademic Stress in The Final Years of School: A Systematic Literature ReviewandromedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of AnxietyDocument4 paginiEffects of AnxietyEdelrose LapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Negative Impact of Stress in Academic Performance To StudentsDocument9 paginiThe Negative Impact of Stress in Academic Performance To StudentsPaolo MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- ResearchDocument13 paginiResearchMarion Joy GanayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated Bibliography - ApaDocument4 paginiAnnotated Bibliography - Apaapi-390515319Încă nu există evaluări

- c029 PDFDocument13 paginic029 PDFTherijoy DadanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coping Mechanism To Stress As A Working StudentDocument10 paginiCoping Mechanism To Stress As A Working StudentRhea PantorillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Mindful Meditation On Adjustment Problem Faced by First Year BDocument5 pagini1 - A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Mindful Meditation On Adjustment Problem Faced by First Year BJohn Ace Revelo-JubayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Running Head: Stress Management Techniques in Graduate Students 1Document10 paginiRunning Head: Stress Management Techniques in Graduate Students 1api-282753416Încă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSIDocument5 paginiInternational Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSIinventionjournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Predictors of Stress in College Students: Dalia Saleh, Nathalie Camart and Lucia RomoDocument8 paginiPredictors of Stress in College Students: Dalia Saleh, Nathalie Camart and Lucia RomoBagus P. SantosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coping Strategies and Psychological Well-Being Among Teacher Education StudentsDocument14 paginiCoping Strategies and Psychological Well-Being Among Teacher Education StudentsVaness143Încă nu există evaluări

- The Study of Stress Management On Academic Success ofDocument11 paginiThe Study of Stress Management On Academic Success ofErwin llabonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review On Stress Among College StudentsDocument5 paginiLiterature Review On Stress Among College StudentsaflssjrdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stress Coping Style 2Document20 paginiStress Coping Style 2Stephanie Bragat0% (1)

- Acadamic StressDocument23 paginiAcadamic StressaleneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practitioner Review: Twenty Years of Research With Adverse Childhood Experience Scores - Advantages, Disadvantages and Applications To PracticeDocument15 paginiPractitioner Review: Twenty Years of Research With Adverse Childhood Experience Scores - Advantages, Disadvantages and Applications To PracticeMarlon Daniel Torres PadillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Academic Stress of College StudentsDocument11 paginiAcademic Stress of College StudentsYatheendra KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Papanastasiou AnxietyDocument15 paginiPapanastasiou AnxietyOsamaMazhariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Stress On Academic Performance of Senior High School Students in Marcia B. Villanueva National High SchoolDocument4 paginiThe Impact of Stress On Academic Performance of Senior High School Students in Marcia B. Villanueva National High SchoolAldrin Ejurango100% (1)

- Examination Stress and Test AnxietyDocument7 paginiExamination Stress and Test AnxietyUjjwal K HalderÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Profile of The Test-Anxious Student - Depreeuw1984Document12 paginiA Profile of The Test-Anxious Student - Depreeuw1984WinnieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stressors of Third Year CollegeDocument24 paginiStressors of Third Year CollegeMiko Salvacion BrazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- E04513236 PDFDocument5 paginiE04513236 PDFJohnjohn MateoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On College StressDocument7 paginiResearch Paper On College Stressgvznen5k100% (1)

- Psychometric Properties of The Inventory of College Students' Recent Life Experiences (Icsrle) : LithuanianDocument20 paginiPsychometric Properties of The Inventory of College Students' Recent Life Experiences (Icsrle) : Lithuanianأحمد خيرالدين عليÎncă nu există evaluări

- 963 FullDocument20 pagini963 FullfirmezaivanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stress in College Students Research PaperDocument6 paginiStress in College Students Research Paperttdqgsbnd100% (1)

- AD Reseach Final ProjectDocument14 paginiAD Reseach Final ProjectSundar WajidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Chapter 2 FinalDocument18 paginiResearch Chapter 2 FinalMa Eulydan Bayuga50% (2)

- Research 12Document13 paginiResearch 12Krianne KilvaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Self-Concept in The Challenges and Coping Mechanisms of Nursing StudentsDocument20 paginiThe Role of Self-Concept in The Challenges and Coping Mechanisms of Nursing StudentsNamoAmitofouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Academic Stress, Anxiety and Depression Among College StudentsDocument9 paginiAcademic Stress, Anxiety and Depression Among College StudentsSamar HamadyÎncă nu există evaluări

- RefDocument5 paginiRefAlliah grace BulanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MehtabDocument3 paginiMehtabZahra AfrozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oral ScriptDocument7 paginiOral ScriptArdent BautistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DepressionDocument10 paginiDepressionKate Lucernas MayugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coping With Stress in AdolescentsDocument9 paginiCoping With Stress in AdolescentsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student EducationDocument14 paginiStudent EducationKathrina Bianca DumriqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regie - Main Pages THESISDocument43 paginiRegie - Main Pages THESISRedgie G. GabaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transforming Truancy: Exploring Factors and Strategies That Impact Truancy Among YouthDe la EverandTransforming Truancy: Exploring Factors and Strategies That Impact Truancy Among YouthÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Agony of Teacher's STRESS: A Comparative AnalysisDe la EverandThe Agony of Teacher's STRESS: A Comparative AnalysisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five Paragraph EssayDocument7 paginiFive Paragraph EssayYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Destination UK - England Lesson PlanDocument4 paginiDestination UK - England Lesson PlanYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teste de MorfologieDocument6 paginiTeste de MorfologieYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planif IV SC 21 FairylandDocument9 paginiPlanif IV SC 21 FairylandYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planificare 8Document3 paginiPlanificare 8You YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planif Unit 4Document16 paginiPlanif Unit 4You YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of English PrepDocument8 paginiAnalysis of English PrepYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romeo Si Julieta-ChestionarDocument1 paginăRomeo Si Julieta-ChestionarYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planificarea Unitatilor de Invatare: Unit 1: Nice To Meet You All - 2 HDocument15 paginiPlanificarea Unitatilor de Invatare: Unit 1: Nice To Meet You All - 2 HYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavioral Sciences Hispanic Journal Of: Coping With Discrimination Among Mexican Descent AdolescentsDocument17 paginiBehavioral Sciences Hispanic Journal Of: Coping With Discrimination Among Mexican Descent AdolescentsYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- And Social Support Bullying and Stress in Early Adolescence: The Role of CopingDocument25 paginiAnd Social Support Bullying and Stress in Early Adolescence: The Role of CopingYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test VIDocument1 paginăTest VIYou YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dw-Booklet-Of-9-Mark-Essays-P1 2Document13 paginiDw-Booklet-Of-9-Mark-Essays-P1 2candyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test - Northstar 4 - Chapter 4 - Animal Intelligence - QuizletDocument2 paginiTest - Northstar 4 - Chapter 4 - Animal Intelligence - QuizlethaletuncerÎncă nu există evaluări

- TAGOLOAN Community College: Course Code: Path-Fit 1 Movement Competency TrainingDocument7 paginiTAGOLOAN Community College: Course Code: Path-Fit 1 Movement Competency TrainingIrene PielagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chris Argyris Double Loop Learning in Organisations PDFDocument11 paginiChris Argyris Double Loop Learning in Organisations PDFChibulcutean CristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Participative or Democratic Leadership 17Document2 paginiParticipative or Democratic Leadership 17p.sankaranarayananÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3-Step Guide To Calming Your Pet's AnxietyDocument5 pagini3-Step Guide To Calming Your Pet's AnxietyMarthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- William G. Braud - Human Interconnectedness: Research IndicationsDocument22 paginiWilliam G. Braud - Human Interconnectedness: Research IndicationsFlikk34100% (1)

- Heal Thyself Serbian Web EdDocument3 paginiHeal Thyself Serbian Web EdAzra Plese Dzakulic100% (1)

- School Motivation Learning Strategies Inventory SmalsiDocument35 paginiSchool Motivation Learning Strategies Inventory SmalsiTudor Corina Alexandra100% (1)

- Review of Best Practices For SupervisionDocument46 paginiReview of Best Practices For SupervisionCorey Shegda100% (1)

- The Systematic Process of Motivational Design: by John M. KellerDocument12 paginiThe Systematic Process of Motivational Design: by John M. KellerSeungRina PandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advantage of Ecological System TheoryDocument2 paginiAdvantage of Ecological System TheoryRonnie Serrano Pueda100% (2)

- Framing Childhood Resilience Through Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory: A Discussion PaperDocument14 paginiFraming Childhood Resilience Through Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory: A Discussion PaperShanina RosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study On Emotional and Social Transition in Early AdulthoodDocument2 paginiA Study On Emotional and Social Transition in Early AdulthoodIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 Thinking About AssessmentDocument43 pagini02 Thinking About AssessmentHilene PachecoÎncă nu există evaluări

- GDS 4 & GDS 15 EnglishDocument4 paginiGDS 4 & GDS 15 EnglishyenaxoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Miciah Lee LawsuitDocument34 paginiMiciah Lee LawsuitNews 4Încă nu există evaluări

- Family Health Assessment Part I PDFDocument10 paginiFamily Health Assessment Part I PDFsszabolcsiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decision Making and Conflict ManagementDocument28 paginiDecision Making and Conflict ManagementedmundÎncă nu există evaluări

- When Prey Turns Predatory Workplace Bullying As A Predictor of Counteraggression Bullying Coping and Well BeingDocument27 paginiWhen Prey Turns Predatory Workplace Bullying As A Predictor of Counteraggression Bullying Coping and Well Beingteslims100% (1)

- For 10 Points Each, Answer The FollowingDocument5 paginiFor 10 Points Each, Answer The FollowingJohn Phil PecadizoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ResilienceDocument19 paginiResilienceSanya KakkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Observation SkillsDocument22 paginiObservation Skillsteohboontat100% (1)

- Attachement 261Document22 paginiAttachement 261Sheron LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit III Module in EthicsDocument22 paginiUnit III Module in EthicsTelly PojolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anh 11 Global UNIT 8. Becoming Independent - TEST 1Document4 paginiAnh 11 Global UNIT 8. Becoming Independent - TEST 1hoainhon2411Încă nu există evaluări

- Practice Paper 1 - Guided Textual AnalysisDocument4 paginiPractice Paper 1 - Guided Textual AnalysisabidmothishamÎncă nu există evaluări