Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Sede Prime N Menos

Încărcat de

karabanmanTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Sede Prime N Menos

Încărcat de

karabanmanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Physical Activity, Sedentary

Behavior, and Symptoms of Major

Depression in Middle Childhood

Tonje Zahl, MSC,a,b Silje Steinsbekk, PhD,b Lars Wichstrm, PhDa,b

OBJECTIVE: The prospective relation between physical activity and Diagnostic and Statistical abstract

Manual of Mental Disorders-defined major depression in middle childhood is unknown,

as is the stability of depression. We therefore aimed to (1) determine whether there are

reciprocal relations between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary

behavior, on one hand, and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth

Edition defined symptoms of major depressive disorder, on the other and (2) assess the

extent of stability in depressive symptoms from age 6 to 10 years.

METHODS: A community sample of children living in Trondheim, Norway, comprising a total

of 795 6-year-old children was followed up at 8 (n = 699) and 10 (n = 702) years of age.

Physical activity was recorded by accelerometry and symptoms of major depression were

measured through semistructured clinical interviews of parents and children. Bidirectional

relationships between MVPA, sedentary activity, and symptoms of depression were

analyzed through autoregressive cross-lagged models, and adjusted for symptoms of

comorbid psychiatric disorders and BMI.

RESULTS: At both age 6 and 8 years, higher MVPA predicted fewer symptoms of major

depressive disorders 2 years later. Sedentary behavior did not predict depression, and

depression predicted neither MVPA nor sedentary activity. The number of symptoms of

major depression declined from ages 6 to 8 years and evidenced modest continuity.

CONCLUSIONS: MVPA predicts fewer symptoms of major depression in middle childhood, and

increasing MVPA may serve as a complementary method to prevent and treat childhood

depression.

aNTNU Social Reseach, Trondheim, Norway; and bDepartment of Psychology, Norwegian University of Science WHATS KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Moderate-

and Technology, Trondheim, Norway to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) reduces the

likelihood of depression in adolescents and adults,

Ms Zahl carried out initial analyses and drafted initial manuscript; Dr Steinsbekk conceptualized,

designed, and supervised the study; Dr Wichstrm obtained funding and conceptualized, and is cross-sectionally associated with depression

designed, and supervised the study; and all authors approved the nal manuscript as submitted. in children. However, the prospective relation

between MVPA, sedentary time, and depression in

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-1711

childhood is unknown.

Accepted for publication Nov 8, 2016

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: Objectively measured

Address correspondence to Tonje Zahl, MSC, NTNU Social Research, Dragvoll All 38B, 7048

MVPA at ages 6 and 8 predict fewer symptoms

Trondheim, Norway. E-mail: tonje.zahl@samfunn.ntnu.no

of depression in children 2 years later, whereas

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). sedentary activity is prospectively unrelated to

Copyright 2017 by the American Academy of Pediatrics depression. Depression does not forecast reduced

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no nancial relationships relevant physical activity in children.

to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This research was supported by grants 228685 and 213793 from the Research Council To cite: Zahl T, Steinsbekk S, Wichstrm L. Physical Activity,

of Norway and grant FO5148 from the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation. Sedentary Behavior, and Symptoms of Major Depression in

Middle Childhood. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161711

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 139, number 2, February 2017:e20161711 ARTICLE

Both observational and treatment studies have nearly exclusively interviews) and accelerometry-

studies13 indicate that physical measured depression by means recorded MVPA and sedentary

activity (PA)and moderate-to- of rating scales; however, the activity in a large community sample

vigorous PA (MVPA), in particular correspondence between rating of Norwegian children monitored

may reduce the likelihood of major scale scores and the results from biannually from the ages of 6 to 10

depressive disorder (MDD) and/or clinical diagnostic interviews are years controlling for BMI and other

reduce the symptoms of MDD only moderate.17 Second, studies psychiatric symptoms.

in adolescents4 and adults.57 It of the PA-depression relationship

has recently become increasingly in children and adolescents have

clear that depression can also mainly used indirect methods to METHODS

be present in young children.8,9 measure childrens PA (ie, parent

Participants, Recruitment, and

Preventive10 and treatment efforts11 report or self-report, which are

Procedure

for childhood depression are only only moderately associated with

modestly effective, which suggests objectively measured PA); in The Trondheim Early Secure

that alternative or complementary fact, PA in community children Study consists of children from

interventions must be sought. may be overestimated by using the 2003 and 2004 birth cohorts

MVPA might possibly serve as a indirect methods.18 Hence, to avoid in Trondheim, Norway (n = 3456)

strategy for preventing or reducing confounding due to reporting bias, that were recruited by invitation

childhood depression. Indeed, a the PAdepression relationship letter, together with the Strengths

meta-analysis of randomized and should be investigated by using and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

quasiexperimental studies12 among objective measures of PA. Third, 416 version.26 Written consent

children in late childhood and early sedentary activity and MVPA are to participate was obtained when

adolescence suggested a small short- negatively, but far from perfectly, attending ordinary community health

term effect of PA interventions. correlated.19 In other words, some checkups for their 4-year-olds and

Given the waxing and waning of children may be periodically highly the completed SDQ was delivered. As

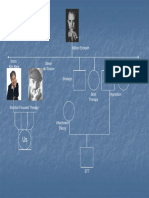

depression,13 it is important also to active but may nonetheless spend can be seen in Fig 1, the vast majority

discern whether long-term effects are much time engaged in sedentary (n = 3358, 97.2%) of children who

present. Toward this end, prospective behavior. A substantial amount of were invited to participate appeared

community studies might prove research has focused on MVPA; at the citys well-child clinics. The

valuable. Importantly, psychomotor however, several studies have SDQ total problem scores (20 items)

retardation is 1 symptom of MDD,14 revealed that sedentary behavior, were divided into 4 strata (cutoffs:

and depressed children show not necessarily MVPA, might predict 0 to 4, 5 to 8, 9 to 11, and 12 to

higher levels of motor inactivity depression.20,21 Thus, we will 40), where drawing probabilities

than controls,6,15 which might investigate the extent to which time increased with increasing SDQ

explain the association reported. spent in sedentary activities predicts scores (0.37, 0.48, 0.70, and 0.89

Longitudinal studies are therefore symptoms of MDD over and above in the 4 strata) to increase sample

needed to reveal whether depression the effects of MVPA. Fourth, there is variability. The PA measurements

predicts reduced PA and whether considerable comorbidity between were included beginning with the

reduced PA increases the risk for depression and other psychiatric second wave of the data collection

depression in children, as has been disorders in children,22,23 and (6 years) and onward; therefore, the

shown in adolescents and adults.5,6,16 these disorders might be related to data used in the present inquiry were

Moreover, to our knowledge, no PA, confounding the relationship taken from 6-year (2009 to 2011,

longitudinal study has examined between depression and PA as a n = 795), 8-year (2011 to 2013, n =

the relationship between PA and result. Fifth, although the evidence is 699), and 10-year (2013 to 2015,

depression in middle childhood by mixed,24 a bidirectional relationship n = 702) assessments. In all, 799

using a community based sample. between childhood depression children had usable data from at least

and BMI is indicated,25 and BMI 1 measurement, and thus constitute

To identify the potentially beneficial should therefore be controlled for. the analytical sample. Attrition was

effects of PA on depression (and vice To overcome these obstacles, we not selective according to the study

versa) in nonreferred children, we investigate the prospective reciprocal variables, except that more hours

examine the bidirectional relation relations between Diagnostic and in MVPA at age 8 predicted attrition

between MVPA and symptoms Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, at age 10 (odds ratio = 2.38; 95%

of depression, while addressing Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) defined confidence interval [CI]: 1.22 to 4.83,

several important methodological symptoms of major depression P = .01); a bias that was adjusted

issues. First, previous observational (obtained by using diagnostic for in the analyses (see Statistical

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

2 ZAHL et al

processed by using accelerometer

analysis software (ActiGraph LLC,

Pensacola, FL).

Symptoms of MDD

The Preschool Age Psychiatric

Assessment (PAPA),31 a psychiatric

interview completed by parents using

a structured protocol, with both

mandatory and optional follow-up

questions, was used to assess MDD

symptoms at 6 years. A sum score

of DSM-IV defined MDD symptoms

constituted the outcome. At 8 and 10

years of age, the Child and Adolescent

Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA)32

was used. Both parents and children

were interviewed and a symptom

was considered to be present if it was

reported by either child or parent.

The PAPA and CAPA interviewers

(n = 9) had at least a Bachelors

degree in a relevant field and were

instructed by the developers of the

PAPA and CAPA. For the PAPA, 9%

of the interview audio recordings

were recoded by blinded raters, as

were 15% of the CAPA interviews.

The interrater reliability between

multiple pairs of raters was 0.90 for

symptoms of MDD in the PAPA and

0.83 in the CAPA.

FIGURE 1

Sample recruitment and follow-up.

Symptoms of Other Psychiatric

Disorders

Analysis). The study was approved minutes of activity per day were

Symptoms of anxiety (consisting

by the Regional Committee of included. Detailed information on

of number of symptoms of social

Medical and Health Research Ethics, accelerometer compliance is shown

phobia, separation anxiety,

Mid-Norway. in Supplemental Table 3. Because

generalized anxiety, and specific

young childrens activity is often

Measurements phobias), attention-deficit/

intermittent with short bursts, we hyperactivity (ADHD), oppositional

Physical Activity employed the commonly used 10 defiant (ODD), and conduct disorders

The children were instructed to wear seconds epoch length.27 We applied (CDs) were assessed following the

an ActiGraph GT3X accelerometer the Evenson et al29 cutoff point of same procedures as for symptoms

(Manufacturing Technology, Inc, 2296 cpm for MVPA because it of MDD. Only the parents were

Fort Walton Beach, FL) around their has shown superior classification interviewed by using the CAPA with

waist for 7 consecutive days, 24 ability in children across the ages respect to ADHD. The interrater

hours a day, and only remove it relevant to the current study.30 reliabilities for PAPA/CAPA ranged

when bathing or showering. Only Minutes per day with 100 cpm from 0.85 to 0.97.

daytime activity (06:0023:59) was was considered sedentary activity,

included. Sequences of consecutive a cutoff that is widely used and has Body Mass Index

zero counts lasting 20 minutes excellent classification accuracy.30 In The childrens weight was measured

were interpreted as nonwear time.27,28 the analyses, MVPA and sedentary by using a digital scale (Tanita

Only those participants with 3 activity were represented in BC20MA), and the height was

days of recordings and 480 hours per day intervals. Data were assessed by using the Heightronic

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 139, number 2, February 2017 3

Digital Stadiometer (QuickMedical

Model 235A). Correction for indoor

clothing (0.5 kg) was applied. BMI

was calculated as kg/m2.

Statistical Analysis

Reciprocal relations between PA

and the symptoms of MDD were

examined in Mplus 7.31,33 using FIGURE 2

Autoregressive cross-lagged relations between MVPA, sedentary behavior, and major depressive

autoregressive cross-lagged analysis symptoms. MVPA and sedentary activity were represented in hours per day intervals. Correlations

within a structural equation among the variables within each time point and the nonsignicant paths are not shown to simplify

framework. The symptoms of MDD, the model illustration, as are the autoregressive paths from 6 to 10 years.

MVPA, and sedentary activity at age

10 were regressed on measures TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics

of these variables and covariates Descriptives of Study Variables (Possible Range) N M SD

at age 8, whereas age 8 measures

1. Number of MDD symptoms 6 y (0 to 9) 793 0.52 0.73

were regressed on measures at age 2. Number of MDD symptoms 8 y (0 to 9) 697 0.46 0.79

6, as shown in Fig 2. To allow for 3. Number of MDD symptoms 10 y (0 to 9) 629 0.52 0.90

sleeper effects (ie, the effects from 4. MVPA 6 y (hours per day) 697 1.19 0.40

age 6 to age 10 measures bypassing 5. MVPA 8 y (hours per day) 607 1.18 0.43

6. MVPA 10 y (hours per day) 684 1.09 0.40

measures at age 8), autocorrelated

7. Sedentary 6 y (hours per day) 689 8.58 0.84

paths were allowed from ages 6 to 8. Sedentary 8 y (hours per day) 607 9.22 1.06

10. Measures obtained at the same 9. Sedentary 10 y (hours per day) 634 9.94 1.07

time point in time (ie, at ages 6, 8, 10. Anxiety 6 y (0 to 21) 793 0.87 1.52

and 10, respectively) were allowed 11. Anxiety 8 y (0 to 21) 697 0.89 1.25

12. ADHD 6 y (0 to 18) 793 1.30 2.24

to correlate. To examine overall

13. ADHD 8 y (0 to 18) 688 1.20 2.40

changes in level of MDD, sedentary 14. CD 6 y (0 to 9)a 793 0.22 0.50

activity and MVPA latent growth 15. CD 8 y (0 to 15) 697 0.30 0.60

curve analyses were conducted. 16. ODD 6 y (0 to 8) 793 0.96 0,47

Because the attrition analyses 17. ODD 8 y (0 to 8) 697 1.08 1.39

18. BMI 6 y 658 15.60 1.51

indicated that the data were missing

19. BMI 8 y 675 16.62 1.97

not at random (MNAR), missing a Six items in the CD scale were removed at age 6 because they were not considered age appropriate.

data were handled according

to a full information maximum

likelihood procedure. Because RESULTS years (Mgrowth= 0.32 [95% CI, 0.27

counts of depressive symptoms are The descriptive statistics are shown to 0.37]) and increased further from

right skewed,34 a robust maximum in Table 1. The rate of DSM-IV defined ages 8 to 10 years (Mgrowth= 0.36

likelihood estimator was used, which MDD diagnosis, ranged from 0.3% [95% CI, 0.30 to 0.42]). Regarding

is robust to moderate deviations (age 6) to 0.4% (age 8), underscoring rank order stability, Table 2 shows

from normality. As oversampling was the need, at this age, to analyze MDD that the symptoms for MDD and

applied on the basis of mental health continuously as symptom counts. sedentary activity were modestly

problems, the data were weighted Supplementary piecewise growth stable, whereas we found higher

back with a factor determined curve analyses revealed that MDD stability for MVPA.

as the number of children in the decreased from ages 6 to 8 years

population in each stratum divided (Mgrowth= 0.13 [95% CI, 0.17 to Cross-Sectional Findings

by the number of participants in 0.10]) but increased from ages 8 The symptoms of MDD were

each stratum to arrive at correct to 10 years (Mgrowth= 0.03 [95% CI, negatively correlated with MVPA at

population estimates. To examine 0.00 to 0.06]). Minutes of MVPA per ages 8 and 10, but were unrelated

gender differences in the estimates, a day did not change from ages 6 to 8 to sedentary activity (Table 2). As

Wald test was employed to compare years (Mgrowth= 0.17 [95% CI, 1.35 expected, the symptoms of MDD

the fit of 2 models, one in which the to 1.01]) but decreased from ages 8 covaried with the symptoms of other

path at hand was fixed as identical for to 10 years (Mgrowth= 2.62 [95% CI, disorders at all time points. The

the 2 genders and the other in which 3.75 to 1.49]). Finally, sedentary symptoms of these other disorders

the path was freely estimated.26 activity increased from ages 6 to 8 were generally unrelated to MVPA

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

4 ZAHL et al

0.17***

0.10*

and sedentary activity, although we

0.84***

0.08

0.03

0.02

0.03

0.01

0.04

0.05

0.05

0.03

0.04

0.26

0.07

0.02

0.06

0.01

1

found higher MVPA among 6-year-old

children who had more symptoms of

0.13**

0.09*

0.06

0.01

0.03

0.04

0.01

anxiety disorders and less sedentary

0.06

0.03

0.05

0.00

0.05

0.01

0.06

0.03

0.04

0.00

1

activity among those 6-year-old

children who had elevated symptoms

0.21***

0.27***

0.17***

0.35***

0.30***

0.35***

0.16***

0.33***

0.35***

0.05

0.04

0.16*

0.10*

of ADHD.

0.07

0.04

0.04

1

19

Prospective Associations

0.11**

0.44***

0.21***

0.19***

0.36***

0.27***

0.38***

0.30***

0.34***

0.23***

0.02

0.05

0.09*

0.04

0.06

1

The main results from the

autoregressive cross-lagged

0.19***

0.22***

0.27***

0.29***

0.18***

0.01

0.04

0.06

0.12**

0.14*

0.08*

0.08*

model examining the bidirectional

0.06

0.06

1

relationships between MVPA,

sedentary activity, and major

0.17***

0.18***

0.04

0.12**

0.10*

0.09*

0.09*

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.04

0.03

0.01

depression are shown in Fig 2.

1

For complete model results, see

18

Supplemental Table 4.

0.09*

0.25***

0.29***

0.19***

0.28***

0.47***

0.58***

0.01

0.06

0.09

0.07

0.06

1

17

The model did fit the data well (2 =

21.76, df = 24, P = .59, comparative

0.10**

0.35***

0.20***

0.14***

0.33***

0.35***

0.04

0.07

0.07

0.10**

16

0.08

fit index = 1.00, Tucker-Lewis index =

1

1.007, root mean square error of

15

approximation = 0.000). At both 6

0.23***

0.47***

0.21***

0.32***

0.01

0.01

0.06

0.07

0.07

0.01

and 8 years, higher levels of MVPA

14

predicted fewer symptoms of MDD 2

years later. The reduction was 0.20

0.48***

0.19***

0.06

0.03

0.07

0.06

0.00

0.12*

0.01

1

13

symptoms of depression per daily

hour spent in MVPA. The effect of

0.17***

0.47***

0.16**

0.22**

12

0.28***

0.00

MVPA on depression from age 8 to

0.06

0.06

10 was seemingly stronger than the

11

effect from age 6 to 8. Standardized

0.42***

0.15***

0.10*

0.30***

0.03

coefficients revealed effect sizes of

0.00

0.03

0.08 (at age 6 to 8) and 0.11 at

10

age 8 to 10), respectively. However,

0.40***

0.18***

0.12**

0.04

0.02

0.03

when comparing a model in which

1

9

these 2 path coefficients were fixed

as equal with a model in which they

0.17***

0.37***

0.47***

0.06

0.03

8

were freely estimated, no significant

difference was found (Wald = 0.41,

7

0.16**

df = 1, P = .41). A similar procedure

0.40***

-0.10**

TABLE 2 Bivariate Correlations Between Study Variables

0.02

was used to test for the gender-

6

specific effects of MVPA on later

0.08**

0.01

0.07

symptoms of MDD, and no such

1

5

differences were found (6 to 8 years:

Wald = 0.47, df = 1, P = .49; 8 to 10

0.19***

0.25***

4

years: Wald = 0.34, df = 1, P = .56).

Because MDD symptoms are heavily

3

right-skewed with many children

0.27***

evincing no symptoms and just a

2

few evincing many symptoms, there

is a possibility that the obtained

1

1

, not applicable.

effect of MVPA on MDD was due to

7. Sedentary

8. Sedentary

9. Sedentary

6. MVPA 10 y

12. ADHD 6 y

13. ADHD 8 y

3. MDD 10 y

4. MVPA 6 y

5. MVPA 8 y

16. ODD 6 y

17. ODD 8 y

18. BMI 6 y

19. BMI 8 y

10. Anxiety

11. Anxiety

1. MDD 6 y

2. MDD 8 y

skewness and count nature of MDD

*** P < .001.

14. CD 6 y

15. CD 8 y

** P < .01.

* P < .05.

10 y

symptoms. We therefore run the path

6y

8y

6y

8y

analysis treating MDD symptoms as

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 139, number 2, February 2017 5

having a negative binominal (count) symptoms of MDD, 2 potential adolescents and adults has suggested

distribution. MVPA still predicted mechanisms related to PAs 2 not that sedentary behavior may increase

reduced numbers of MDD symptoms mutually exclusive components depression.20 It is thus likely that the

from age 6 to 8 (B = 0.58 [95% (the activity and the physical effect of sedentariness on depression

CI: 0.95 to 0.21], P = .001) and components), can be hypothesized. is age-dependent. However, because

from age 8 to 10 (B = 0.58 [95% CI: Treatment studies applying activity psychomotor retardation and loss

1.03 to 0.13], P = .002). Moreover, scheduling have indicated that of energy are among the symptoms

depression did not predict later increasing activity, not necessarily of MDD, it is essential to adjust for

MVPA, and no effects of sedentary just PA, may reduce depression.38 previous MDD when examining

activity on depression, or vice versa, Several explanations for this MDD- sedentary activitys contribution to

were detected. reducing effect have been proposed: MDD, which has been investigated

(1) Engaging in activities may distract only to a limited extent.21,49 Further,

DISCUSSION from ruminating over negative in many of these prospective

events, and ruminations may worsen studies, self-reports of inactivity

To aid the preventive and treatment or prolong depression.39,40 (2) A and depression have been applied

efforts of depression among children, substantial part of MVPA in children that may inflate their relationship

we examined the bidirectional consists of play or sports activities,41 on a prospective basis, due to the

relations between MVPA, sedentary and playing or engaging in sports common methods that are employed.

activity, and MDD symptoms over may bolster self-efficacy and self- Moreover, it is essential to adjust

3 waves of data collection in a large esteem in children, which has been for lack of MVPA when estimating

community sample of children. suggested to prevent depression.42,43 the effects of sedentariness because

Higher levels of MVPA at 6 and 8, (3) Finally, when children are MVPA and sedentary activity are

respectively, predicted fewer MDD physically active, they tend to be negatively correlated. In sum, the lack

symptoms 2 years later. No effects of with other children.41 Although peer- of comparable studies underscores

sedentary activity were found for MDD rejections and bullying also occur in the need to replicate our findings.

symptoms, and MDD symptoms did sports,44 physically active children

not predict later PA (or lack thereof). may be more socially integrated in Levels of PA and Symptoms of MDD

peer groups than less active children. During Middle Childhood

MVPA Predicts Fewer Depressive

Symptoms Such peer acceptance, which is The level of symptoms of MDD

likely to result in social support, is a was stable from 6 to 10 years.

The identified effects of PA on

potential buffer against depression.45 MDD symptoms evidenced some

depression extend findings from homotypical continuity, which

observational studies of adolescents Regarding the physical component extends the findings from short-term

and adults35 by documenting that of PA, several physiologic and longitudinal studies on MDD in young

this relationship is also present in biochemical mechanisms have been children.9,50 The observed reduction

middle childhood. We further add proposed, such as the demonstration in MVPA and increase in sedentary

to existing knowledge by showing of PA leading to higher availability of behavior are consistent with findings

that predictive effects are present neurotransmitters, which is assumed from previous research.19

when we examine interview-based to have antidepressant effects.46,47 In

DSM-defined symptoms of MDD addition, regular PA has a favorable Limitations

rather than questionnaires, and impact on neuronal functions and Although individuals fulfilling the DSM

when applying objectively measured structure along with increased cutoff of 5 or more MDD symptoms

PA, and account for the potential cognitive functions.48 do not seem qualitatively different

effects of other psychiatric disorders

from those with just under cutoffs,51

and BMI. Although the effects of No Prospective Relation Between and even though the correlates and

MVPA were small, they are similar Sedentary Activity and Symptoms of predictors of subclinical depression

to those obtained by psychosocial MDD

are similar to those of the disorder,52

intervention programs in children36

Our study is the first to objectively our findings do not necessarily

and adolescents.37 Along with the

examine sedentary activity and generalize to the disorder itself. Thus,

fact that nearly all children can be

later depression in early and research with substantially larger

targeted in efforts to increase MVPA,

middle childhood, and we find samples is required to determine

the gains at the population level

no prospective relation between whether objectively measured MVPA

might be substantial.

sedentary behavior and symptoms would decrease the risk of MDD in

Although the current study did not of MDD. Although there are some community children. Nonetheless,

address why PA may reduce future important exceptions,49 research on because previous research has

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

6 ZAHL et al

shown that there is a continuity in enhancement58 or increased social

interactions59 may explain at least

ABBREVIATIONS

depressive symptoms from childhood

to adolescence and later adulthood,53 some of the results. The prevalence of ADHD:attention-deficit/

that an elevated level of MDD psychiatric disorders is generally low hyperactivity disorder

symptoms increases the risk of in Norway,60 but whether the impact CAPA:Child and Adolescent

later MDD,54,55 and that subclinical of MVPA on depressive symptoms also Psychiatric Assessment

depression may entail substantial differ between countries should be CD:conduct disorder

impairment (also in the long run),56 examined in future studies. CI:confidence interval

our findings suggest that increasing DSM-IV:Diagnostic and

MVPA at the population level may lead Statistical Manual of

to reduced symptoms of depression CONCLUSIONS Mental Disorders, Fourth

and the impairment that accompanies Edition

MVPA predicts fewer future MDD

these symptoms in some children. MDD:major depressive

symptoms in middle childhood,

Second, data were MNAR, which may disorder

and such symptoms are moderately

MNAR:missing not at random

have led to biased results. However, stable from the ages of 6 to 10 years.

MVPA:moderate-to-vigorous

the selectivity of this attrition was Sedentary activity in children does

physical activity

modest and we used all available not alter the risk of future symptoms

PA:physical activity

data in a full information maximum of depression, and depression does

PAPA:Preschool Age Psychiatric

likelihood procedure, which leads to not influence the likelihood of MVPA

Assessment

less biased results than complete case or inactivity. Although the effect

ODD:oppositional defiant

analysis when the data are MNAR.57 was small, our results indicate that

disorder

Nonetheless, we cannot exclude that increasing MVPA in children at

SDQ:Strengths and Difficulties

such bias along with unmeasured the population level may prevent

Questionnaire

confounders such as self-image depression, at least at subclinical levels.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Silveira H, Moraes H, Oliveira N, 5. Pereira SMP, Geoffroy MC, Power from preschool to rst grade.

Coutinho ESF, Laks J, Deslandes C. Investigation of bidirectional Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28(4 pt

A. Physical exercise and clinically associations between depressive 2):15171530

depressed patients: a systematic symptoms and physical activity from 10. Beardslee WR, Gladstone TRG.

review and meta-analysis. age 11 to 50 years in the 1958 British Prevention of childhood depression:

Neuropsychobiology. 2013;67(2): Birth Cohort. Lancet. 2013;382:80 recent ndings and future prospects.

6168 Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):11011110

6. Azevedo Da Silva M, Singh-Manoux

2. Wegner M, Helmich I, Machado S, Nardi A, Brunner E, et al. Bidirectional 11. Michael KD, Crowley SL. How

AE, Arias-Carrion O, Budde H. Effects association between physical effective are treatments for child

of exercise on anxiety and depression activity and symptoms of anxiety and and adolescent depression? A meta-

disorders: review of meta-analyses depression: the Whitehall II study. Eur J analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev.

and neurobiological mechanisms. Epidemiol. 2012;27(7):537546 2002;22(2):247269

CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 7. Pinto Pereira SM, Geoffroy MC, 12. Brown HE, Pearson N, Braithwaite RE,

2014;13(6):10021014 Power C. Depressive symptoms and Brown WJ, Biddle SJ. Physical activity

3. Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Archer T. physical activity during 3 decades in interventions and depression in

Physical exercise intervention in adult life: bidirectional associations children and adolescents: a systematic

depressive disorders: meta-analysis in a prospective cohort study. JAMA review and meta-analysis. Sports Med.

and systematic review. Scand J Med Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):13731380 2013;43(3):195206

Sci Sports. 2014;24(2):259272 8. Luby JL, Heffelnger AK, Mrakotsky C, 13. Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson

et al. The clinical picture of depression DE, et al. Childhood and adolescent

4. Jerstad SJ, Boutelle KN, Ness KK,

in preschool children. J Am Acad Child depression: a review of the past 10

Stice E. Prospective reciprocal

Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):340348 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

relations between physical

activity and depression in female 9. Reinfjell T, Krstad SB, Berg-Nielsen Psychiatry. 1996;35(11):14271439

adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. TS, Luby JL, Wichstrm L. Predictors 14. Birmaher B, Brent D. Practice

2010;78(2):268272 of change in depressive symptoms parameter for the assessment and

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 139, number 2, February 2017 7

treatment of children and adolescents 24. Muhlig Y, Antel J, Focker M, 35. Teychenne M, Ball K, Salmon J. Physical

with depressive disorders. J Am Hebebrand J. Are bidirectional activity and likelihood of depression

Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. associations of obesity and depression in adults: a review. Prev Med.

2007;46(11):15031526 already apparent in childhood and 2008;46(5):397411

adolescence as based on high-quality 36. Horowitz JL, Garber J. The prevention

15. Aronen ET, Simola P, Soininen M. Motor

studies? A systematic review. Obesity of depressive symptoms in children

activity in depressed children. J Affect

Rev . 2016;17(3):235249 and adolescents: A meta-analytic

Disorder. 2011;133(12):188196

25. Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. review. J Consult Clin Psychol.

16. Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Coleman KJ,

Overweight, obesity, and depression: a 2006;74(3):401415

Vito D, Anderson K. Determinants of

systematic review and meta-analysis 37. Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN,

physical activity in obese children

of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of

assessed by accelerometer and

Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220229 depression prevention programs for

self-report. Med Sci Sport Excer.

1996;28(9):11571164 26. Goodman R. The strengths and children and adolescents: factors that

difculties questionnaire: a research predict magnitude of intervention

17. Sveen TH, Berg-Nielsen TS, Lydersen

note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. effects. J Consult Clin Psychol.

S, Wichstrm L. Detecting psychiatric

1997;38(5):581586 2009;77(3):486503

disorders in preschoolers: screening

with the strengths and difculties 27. Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Van Dyck 38. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam

questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc D, Calhoon L. Using accelerometers L. Behavioral activation treatments

Psychiatry. 2013;52(7):728736 in youth physical activity studies: a of depression: a meta-analysis. Clin

review of methods. J Phys Act Health. Psychol Rev. 2007;27(3):318326

18. Adamo KB, Prince SA, Tricco AC,

2013;10(3):437450 39. Rood L, Roelofs J, Bgels SM, Nolen-

Connor-Gorber S, Tremblay M. A

comparison of indirect versus direct 28. Ward DS, Evenson KR, Vaughn A, Hoeksema S, Schouten E. The inuence

measures for assessing physical Rodgers AB, Troiano RP. Accelerometer of emotion-focused rumination and

activity in the pediatric population: a use in physical activity: best practices distraction on depressive symptoms

systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes. and research recommendations. in non-clinical youth: a meta-

2009;4(1):227 Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(suppl analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev.

11):S582S588 2009;29(7):607616

19. Bastereld L, Adamson AJ, Frary JK,

et al. Longitudinal study of physical 29. Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak 40. Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to

activity and sedentary behavior in KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of depression and their effects on the

children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1). two objective measures of physical duration of depressive episodes. J

Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/ activity for children. J Sports Sci. Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):569582

content/full/127/1/e24 2008;26(14):15571565 41. Macdonald-Wallis K, Jago R, Sterne

20. Page AS, Cooper AR, Griew P, Jago R. 30. Trost SG, Loprinzi PD, Moore R, Pfeiffer JAC. Social network analysis of

Childrens screen viewing is related to KA. Comparison of accelerometer cut childhood and youth physical activity:

psychological difculties irrespective points for predicting activity intensity a systematic review. Am J Prev Med.

of physical activity. Pediatrics. in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;43(6):636642

2010;126(5). Available at: www. 2011;43(7):13601368 42. Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low

pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/126/5/ 31. Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts self-esteem predict depression

e1011 E, Walter BK, Angold A. Test-Retest and anxiety? A meta-analysis of

21. Sund AM, Larsson B, Wichstrm L. Role Reliability of the Preschool Age longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull.

of physical and sedentary activities Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). J 2013;139(1):213240

in the development of depressive Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 43. Ekeland E, Heian F, Hagen Kre B,

symptoms in early adolescence. 2006;45(5):538549 Abbott Jo M, Nordheim L. Exercise to

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 32. Angold A, Costello EJ. The Child and improve self-esteem in children and

2011;46(5):431441 Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment young people. Cochrane Database Sys

22. Keiley M, Bates J, Dodge K, Pettit G. (CAPA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Rev. 2004(1):CD003683

A cross-domain growth analysis: Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):3948 44. Stirling AE, Bridges EJ, Cruz EL,

externalizing and internalizing 33. Muthn LK, Muthn BO. Mplus Users Mountjoy ML; Canadian Academy of

behaviors during 8 years of Guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthn Sport and Exercise Medicine. Canadian

childhood. J Abnormal Child Psychol. & Muthn; 19982015 Academy of Sport and Exercise

2000;28(2):161179 Medicine position paper: abuse,

34. Benson J, Fleishman J. The

23. Lilienfeld S. Comorbidity between and robustness of maximum likelihood harassment, and bullying in sport. Clin

within childhood externalizing and and distribution-free estimators J Sport Med. 2011;21(5):385391

internalizing disorders: reections and to non-normality in conrmatory 45. Epkins C, Heckler D. Integrating

directions. J Abnormal Child Psychol. factor analysis. Qual Quant. etiological models of social anxiety

2003;31(3):285291 1994;28(2):117136 and depression in youth: evidence

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

8 ZAHL et al

for a cumulative interpersonal risk meta-analytic review. Acta Psychiatr 56. Cuijpers P, Smit F. Subthreshold

model. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. Scand. 2007;115(6):434441 depression as a risk indicator

2011;14(4):329376 52. Shankman SA, Lewinsohn PM, Klein for major depressive disorder: a

DN, Small JW, Seeley JR, Altman SE. systematic review of prospective

46. Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular

Subthreshold conditions as precursors studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand.

neurobiology of depression. Nature.

for full syndrome disorders: a 2004;109(5):325331

2008;455(7215):894902

15-year longitudinal study of multiple 57. Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data:

47. Craft LL, Perna FM. The benets of

diagnostic classes. J Child Psychol our view of the state of the art. Psychol

exercise for the clinically depressed.

Psychiatry. 2009;50(12):14851494 Methods. 2002;7(2):147177

Primary Care Companion J Clin

Psychiatry. 2004;6(3):104111 53. Dekker MC, Ferdinand RF, van Lang ND, 58. Kirkcaldy BD, Shephard RJ, Siefen RG.

Bongers IL, van der Ende J, Verhulst The relationship between physical

48. Chaddock-Heyman L, Erickson KI,

FC. Developmental trajectories of activity and self-image and problem

Holtrop JL, et al Aerobic tness is

depressive symptoms from early behaviour among adolescents. Soc

associated with greater white matter

childhood to late adolescence: Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.

integrity in children. Frontiers Human

gender differences and adult 2002;37(11):544550

Neurosci. 2014;8:584

outcome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 59. Monshouwer K, Ten Have M, van

49. Zhai L, Zhang Y, Zhang D. Sedentary 2007;48(7):657666 Poppel M, Kemper H, Vollebergh W.

behaviour and the risk of depression:

54. Luby JL, Gaffrey MS, Tillman R, April LM, Possible mechanisms explaining the

a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med.

Belden AC. Trajectories of preschool association between physical activity

2015;49(11):705709

disorders to full DSM depression at and mental health: ndings from the

50. Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson school age and early adolescence: 2001 Dutch Health Behaviour in School-

GA, Rose S, Klein DN. Psychiatric continuity of preschool depression. Am Aged Children Survey. Clin Psychol Sci.

disorders in preschoolers: continuity J Psychiatry. 2014;171(7):768776 2013;1(1):6774

from ages 3 to 6. Am J Psychiatry. 55. Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook J. 60. Wichstrm L, Berg-Nielsen TS, Angold

2012;169(11):11571164 Adolescent depressive symptoms A, Egger HL, Solheim E, Sveen TH.

51. Cuijpers P, Smit F, van Straten as predictors of adult depression: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders

A. Psychological treatments moodiness or mood disorder? Am J in preschoolers. J Child Psychol

of subthreshold depression: a Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):133135 Psychiatry. 2012;53(6):695705

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 139, number 2, February 2017 9

Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Symptoms of Major Depression in

Middle Childhood

Tonje Zahl, Silje Steinsbekk and Lars Wichstrm

Pediatrics 2017;139;; originally published online January 9, 2017;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-1711

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services /content/139/2/e20161711.full.html

Supplementary Material Supplementary material can be found at:

/content/suppl/2017/01/05/peds.2016-1711.DCSupplemental.

html

References This article cites 57 articles, 2 of which can be accessed free

at:

/content/139/2/e20161711.full.html#ref-list-1

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Psychiatry/Psychology

/cgi/collection/psychiatry_psychology_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2017 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Symptoms of Major Depression in

Middle Childhood

Tonje Zahl, Silje Steinsbekk and Lars Wichstrm

Pediatrics 2017;139;; originally published online January 9, 2017;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-1711

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

/content/139/2/e20161711.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2017 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on June 24, 2017

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Adenoids and Diseased Tonsils: Their Effect on General IntelligenceDe la EverandAdenoids and Diseased Tonsils: Their Effect on General IntelligenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adult ADHD: Diagnostic Assessment and TreatmentDe la EverandAdult ADHD: Diagnostic Assessment and TreatmentEvaluare: 1 din 5 stele1/5 (1)

- Depression Prevalence and Correlates in Young Swiss MenDocument8 paginiDepression Prevalence and Correlates in Young Swiss MenLucille JeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Focused On Repetitive Negative Thinking For Child Depression - A Randomized Multiple-Baseline EvaluationDocument18 paginiAcceptance and Commitment Therapy Focused On Repetitive Negative Thinking For Child Depression - A Randomized Multiple-Baseline EvaluationVíctor CaparrósÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reward Related Attentional Bias at Age 16 P - 2019 - Journal of The American AcaDocument10 paginiReward Related Attentional Bias at Age 16 P - 2019 - Journal of The American AcaSebastián OspinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Longitudinal Follow-Up Study Examining AdolescentDocument9 paginiA Longitudinal Follow-Up Study Examining AdolescentPAULAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prediction of Posttraumatic Stress in Fathers of Children With Chronic DiseasesDocument10 paginiPrediction of Posttraumatic Stress in Fathers of Children With Chronic Diseasesna5649Încă nu există evaluări

- Paternal Postpartum DepressionDocument12 paginiPaternal Postpartum DepressionAlly NaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rao Chen 2009. DialoguesClinNeurosci-11-45Document18 paginiRao Chen 2009. DialoguesClinNeurosci-11-45Javiera Luna Marcel Zapata-SalazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness of Attachment-Based Family Therapy Compared To Treatment As Usual For Depressed Adolescents in Community Mental Health ClinicsDocument22 paginiEffectiveness of Attachment-Based Family Therapy Compared To Treatment As Usual For Depressed Adolescents in Community Mental Health Clinicsellya nur safitriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental HealthDocument7 paginiMental Healthcooperpaige34Încă nu există evaluări

- Diagnosis of Personality Disorder in AdolescentsDocument4 paginiDiagnosis of Personality Disorder in AdolescentsFlo RenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Factors For Comorbid Psychopathology in Youth With Psychogenic Nonepileptic SeizuresDocument6 paginiRisk Factors For Comorbid Psychopathology in Youth With Psychogenic Nonepileptic SeizuresCecilia FRÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2022 (A) - The Effect of Change in PA Behaviour On DS Among European Older Adults (Human Movement) PDFDocument7 pagini2022 (A) - The Effect of Change in PA Behaviour On DS Among European Older Adults (Human Movement) PDFPriscila PintoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neurobiologia SMDDocument2 paginiNeurobiologia SMDLuciana CampagnoloÎncă nu există evaluări

- David - REThink (Mechanisms)Document12 paginiDavid - REThink (Mechanisms)matalacurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prevalence of Adult ADHD in HungaryDocument10 paginiPrevalence of Adult ADHD in Hungaryammarashor78Încă nu există evaluări

- Act - Depresión InfantilDocument14 paginiAct - Depresión InfantilNelly Adriana Cantero AcuñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Author's Accepted Manuscript: Psychiatry Research: NeuroimagingDocument31 paginiAuthor's Accepted Manuscript: Psychiatry Research: NeuroimagingErick PaembonanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Anhedonia: A Qualitative Study Exploring Loss of Interest and Pleasure in Adolescent DepressionDocument11 paginiUnderstanding Anhedonia: A Qualitative Study Exploring Loss of Interest and Pleasure in Adolescent Depressionjavid aminiÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology: Original ArticleDocument8 paginiInternational Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology: Original Articlealejandra sarmientoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depresion JurnalDocument10 paginiDepresion JurnalPaskalia ChristinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Miklowitz, 2019, Early Intervention For Youth at High Risk For Bipolar Disorder - A Multisite Randomized Trial of Family-Focused TreatmentDocument18 paginiMiklowitz, 2019, Early Intervention For Youth at High Risk For Bipolar Disorder - A Multisite Randomized Trial of Family-Focused TreatmentcristianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Childhood Trauma in Adults With ADHD Is Associated With Comorbid Anxiety Disorders and Functional Impairment - VeDocument9 paginiChildhood Trauma in Adults With ADHD Is Associated With Comorbid Anxiety Disorders and Functional Impairment - VeZoe PeregrinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Madjar2019 Article ChildhoodMethylphenidateAdhere PDFDocument9 paginiMadjar2019 Article ChildhoodMethylphenidateAdhere PDFKobi TechiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Psychology Psychiatry - 2012 - Simonoff - Severe mood problems in adolescents with autism spectrum disorderDocument10 paginiChild Psychology Psychiatry - 2012 - Simonoff - Severe mood problems in adolescents with autism spectrum disorderlidiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trauma and IQ (WAIS)Document8 paginiTrauma and IQ (WAIS)TEOFILO PALSIMON JR.Încă nu există evaluări

- Perceived Family Functioning Adolescent Psychopathology and Quality of Life in General Population A 6 Month Follow Up StudyDocument9 paginiPerceived Family Functioning Adolescent Psychopathology and Quality of Life in General Population A 6 Month Follow Up StudyMarisolÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S0165032723003993 MainDocument9 pagini1 s2.0 S0165032723003993 MainDavid Coello-MontecelÎncă nu există evaluări

- © The Author (2016) - Published by Oxford University Press. For Permissions, Please EmailDocument32 pagini© The Author (2016) - Published by Oxford University Press. For Permissions, Please EmailJoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- En InglesDocument13 paginiEn InglesMariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tourette Syndrome in The General Child Population: Cognitive Functioning and Self-PerceptionDocument9 paginiTourette Syndrome in The General Child Population: Cognitive Functioning and Self-PerceptionIdoia PñFlrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lakdawalla CogtheoriesofdepressioninchildrenDocument24 paginiLakdawalla CogtheoriesofdepressioninchildrenRene GallardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise and Adolescent Mental Health: New Evidence From Longitudinal DataDocument13 paginiExercise and Adolescent Mental Health: New Evidence From Longitudinal DataJuan MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 Marlow - Preterm Birth and Childhood Psychiatric DisordersDocument8 pagini2013 Marlow - Preterm Birth and Childhood Psychiatric DisordersdeborahpreitiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dannlowski Et Al - 2012 - Limbic ScarsDocument8 paginiDannlowski Et Al - 2012 - Limbic ScarsKaitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child and Adolescent Mental DisordersDocument8 paginiChild and Adolescent Mental DisordersIsabel AntunesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychodynamic Therapy for Adolescent DepressionDocument16 paginiPsychodynamic Therapy for Adolescent DepressionAzisahhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leyla - Suleymanli - Depression Among TeenagersDocument8 paginiLeyla - Suleymanli - Depression Among TeenagersLeyla SuleymanliÎncă nu există evaluări

- DUP and Negative Symptoms Meta-AnalysisDocument22 paginiDUP and Negative Symptoms Meta-AnalysiselvinegunawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of A Ffective Disorders: Research PaperDocument7 paginiJournal of A Ffective Disorders: Research PaperangelavillateavilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mutismo 2Document10 paginiMutismo 2Camila SiebzehnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Somatic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Anxiety DisordersDocument9 paginiSomatic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Anxiety DisordersDũng HồÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Depression in Adolescents NeuropsikologiDocument9 paginiThe Cognitive Neuropsychology of Depression in Adolescents NeuropsikologiDewi NofiantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unpacking Associations Between Mood Symptoms and Screen Time in Preadolescents-A Network AnalysisDocument39 paginiUnpacking Associations Between Mood Symptoms and Screen Time in Preadolescents-A Network AnalysisOscar Alejandro CordobaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Therapy For Social Anxiety Disorder in Adolescents A Development Case SeriesDocument17 paginiCognitive Therapy For Social Anxiety Disorder in Adolescents A Development Case Serieskahfi HizbullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trajectory MarvDocument9 paginiTrajectory MarvChristman SihiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vangeelen2015 PDFDocument8 paginiVangeelen2015 PDFHafizah Khairi DafnazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Young People's Mental Health Is Finally Getting The Attention It NeedsDocument6 paginiYoung People's Mental Health Is Finally Getting The Attention It NeedsS.CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ni Hms 857824Document18 paginiNi Hms 857824SelyfebÎncă nu există evaluări

- ESTEDocument10 paginiESTELemu456Încă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of The Effects of A Childhood Depression Prevention ProgramDocument15 paginiEvaluation of The Effects of A Childhood Depression Prevention ProgramNatalia VielmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barth Vedoy Norweign AdolescentsDocument12 paginiBarth Vedoy Norweign Adolescentsgameingguy35Încă nu există evaluări

- CCPT as an intervention to reassess ADHD and trauma diagnosesDocument38 paginiCCPT as an intervention to reassess ADHD and trauma diagnosesHira KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Psychiatry - Introduction PDFDocument7 paginiChild Psychiatry - Introduction PDFRafli Nur FebriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experiential Avoidance Mediates The Association Between Paranoid IdeationDocument5 paginiExperiential Avoidance Mediates The Association Between Paranoid IdeationifclarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Association of Depressive Symptoms With Decline of Cognitive Function - Rugao Longevity and Ageing StudyDocument7 paginiAssociation of Depressive Symptoms With Decline of Cognitive Function - Rugao Longevity and Ageing StudyRodrigo Aguirre BáezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depresión Perinatal en PadresDocument18 paginiDepresión Perinatal en PadresClaudio Esteban PicónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Dimensions in Relation To Executive Functioning in Adolescents With ADHDDocument11 paginiAttention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Dimensions in Relation To Executive Functioning in Adolescents With ADHDRaúl VerdugoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Postpartum Depression and Risk of PsychopathologyDocument12 paginiMaternal Postpartum Depression and Risk of PsychopathologyJulián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CONCLUSIONDocument2 paginiCONCLUSIONIgnetheas ApoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health and Mental Illness: Elsevier Items and Derived Items © 2010, 2006 by Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier IncDocument13 paginiMental Health and Mental Illness: Elsevier Items and Derived Items © 2010, 2006 by Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier IncEbsnJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychiatric 12Document33 paginiPsychiatric 12Res TyÎncă nu există evaluări

- PGDip FlyerDocument2 paginiPGDip FlyerClara Del Castillo ParísÎncă nu există evaluări

- How ERP Treatment for OCD Can Incorporate ACT ProcessesDocument5 paginiHow ERP Treatment for OCD Can Incorporate ACT ProcessesnokaionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Questionnaire #1 (ALCOHOLISM)Document4 paginiQuestionnaire #1 (ALCOHOLISM)Gaurav KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- FUNDAMENTALS OF NURSING - Health & Illness - WattpadDocument4 paginiFUNDAMENTALS OF NURSING - Health & Illness - WattpadFrances Joryne DaquepÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Research Theme 2 (Child Protection) Oral - Colon NHS 2022Document10 paginiAction Research Theme 2 (Child Protection) Oral - Colon NHS 2022Mariel VillanuevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Milton Erickson's Influence on Solution Focused TherapyDocument22 paginiMilton Erickson's Influence on Solution Focused TherapyMauro LimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 paginiDaftar PustakaS R PanggabeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study of Insomnia Among Psychiatric Out Patients in Lagos Nigeria 2167 0277.1000104Document5 paginiA Study of Insomnia Among Psychiatric Out Patients in Lagos Nigeria 2167 0277.1000104Ilma Kurnia SariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Help! My Entire Class Has ADHD! HandoutDocument56 paginiHelp! My Entire Class Has ADHD! HandoutCherylDickÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIMH - Reliving Trauma - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)Document3 paginiNIMH - Reliving Trauma - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)George PruteanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADHS Statement of Deficiencies at Sierra TucsonDocument16 paginiADHS Statement of Deficiencies at Sierra TucsonTucsonSentinelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Context of Mental Health Risk in Tsunami-Exposed AdolescentsDocument11 paginiFamily Context of Mental Health Risk in Tsunami-Exposed AdolescentsVirgílio BaltasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cuestionario CEAL - TDAH PDFDocument6 paginiCuestionario CEAL - TDAH PDFOlga Reyna Gonzalez100% (1)

- Literature ReviewDocument11 paginiLiterature Reviewapi-437205356Încă nu există evaluări

- Horticultural Therapy Services: Chicago Botanic GardenDocument9 paginiHorticultural Therapy Services: Chicago Botanic GardenNeroulidi854100% (1)

- UNIKOM - Seftiyandi Kurniawan - AbstrakDocument2 paginiUNIKOM - Seftiyandi Kurniawan - AbstrakSeftiyandi KurniawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning and Design of Psychiatric FacilitiesDocument57 paginiPlanning and Design of Psychiatric FacilitiesLyra EspirituÎncă nu există evaluări

- Executive Functioning PresentationDocument55 paginiExecutive Functioning Presentationnplattos100% (3)

- Child Hood SchizophreniaDocument10 paginiChild Hood SchizophreniarajirajeshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Briesh (2018) Analysis of State Level Guidance Regarding School Based Universal Screening For Social Emotional and Behavioral RiskDocument16 paginiBriesh (2018) Analysis of State Level Guidance Regarding School Based Universal Screening For Social Emotional and Behavioral RiskAna FerreiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abnormal Psychology: Statistical ApproachDocument9 paginiAbnormal Psychology: Statistical ApproachNurul AiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2021 State of Mental Health in America - 0Document54 pagini2021 State of Mental Health in America - 0mybestloveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bipolar DisorderDocument44 paginiBipolar DisorderAinun MaylanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Martens AntisocialandPsychopathicPD ReviewDocument27 paginiMartens AntisocialandPsychopathicPD ReviewPinj BlueÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Stop RuminatingDocument5 paginiHow To Stop RuminatingJunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regional Peacekeepers Collective StrategyDocument17 paginiRegional Peacekeepers Collective StrategyJeremy HarrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postpartum Psychosis Parenting SupportDocument3 paginiPostpartum Psychosis Parenting SupportLyca Mae AurelioÎncă nu există evaluări