Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

CINALLI, GIUGNI (2013), New Challenges For The Welfare State. The Emergence of Youth Unemployment Regimes in Europe

Încărcat de

Eleonora Steva VaianaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

CINALLI, GIUGNI (2013), New Challenges For The Welfare State. The Emergence of Youth Unemployment Regimes in Europe

Încărcat de

Eleonora Steva VaianaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

DOI: 10.1111/ijsw.

12016

I N T E R NAT I O NA L

J O U R NA L O F

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299 SOCIAL WELFARE

ISSN 1369-6866

New challenges for the welfare state:

The emergence of youth

unemployment regimes in Europe?

Cinalli M, Giugni M. New challenges for the welfare state: the Manlio Cinalli1, Marco Giugni2

emergence of youth unemployment regimes in Europe? 1

Sciences Po Paris, CEVIPOF, Paris, France

2

University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

In this article we discuss the emergence of youth unemploy-

ment regimes in Europe, that is, a set of coherent measures

and policies aimed at providing state responses to the problem

of unemployment and, more specifically, youth unemploy-

ment. We classify these measures and policies along two main

dimensions: unemployment regulations and labour market

regulations. Using original data, we show how seven Euro-

pean countries locate on these two dimensions as well as

within the conceptual space resulting from the combination of

the two dimensions. Our findings show cross-national varia-

tions that do not fit the traditional typologies of comparative Key words: unemployment, welfare regimes, political

welfare studies. At the same time, however, the findings allow opportunity structures, labour market, youth

for reflecting upon possible patterns of convergence across Marco Giugni, Department of Political Science and

European countries. In particular, we show some important International Relations, University of Geneva, Uni-Mail, 1211

similarities in terms of flexible labour market regulations. In Geneva 4, Switzerland

this regard, the recent years have witnessed a trend towards a E-mail: marco.giugni@unige.ch

flexibilisation of the labour market, regardless of the prevail-

ing welfare regime. Accepted for publication 4 July 2012

the characteristics of the labour market which can

Introduction

play a major role in determining the opportunities

The main argument of this article is that the politics of and constraints offered to those who are excluded

unemployment, as it has been developing in recent (fully or partly, temporarily or permanently) from the

years, has given shape to deep national differences in labour market.

Europe which fit only partially the main teaching and By focusing on two dimensions of main institutional

the consolidated models of the welfare state that are intervention and policy-making in the field of unem-

discussed in the scholarly literature. Existing charac- ployment, here we discuss the shape of what we call

terisations of the welfare state (e.g., Bonoli & Palier, youth unemployment regimes in Europe. By that we

2001; Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1993) follow a mean a set of coherent measures and policies aimed at

broad and comprehensive approach, including various providing state responses to the problem of unemploy-

aspects of welfare (health, unemployment, social aid, ment and, more specifically, youth unemployment. The

pensions, invalidity, maternity etc.). Other scholars two dimensions along which these state responses

have provided more specific typologies that are focused can be classified relate to the role of unemployment

on state intervention in the field of unemployment (e.g., regulations and labour market regulations. The first

Bambra & Eikemo, 2009; Gallie & Paugam, 2000). dimension refers to specific conditions of access to

These latter works, however, still relied on the assump- rights for the unemployed as well as to the obligations

tion that policies and measures to fight unemployment attached to full enjoyment of these rights, which may be

follow the prevailing institutional approaches to either inclusive or exclusive. The second dimension

welfare in general. Furthermore, they focused on unem- refers to state intervention in the labour market which,

ployment benefits, neglecting other aspects such as as a result, may be characterised as either flexible or

rigid. In line with the theoretical framework that the

authors of this article have developed in previous work

Results presented in this article were obtained from the project (Cinalli & Giugni, 2010; Giugni, Berclaz, & Fglister,

Youth, Unemployment, and Exclusion in Europe: A Multi-

dimensional Approach to Understanding the Conditions and

2009), the combination of these two dimensions yields

Prospects for Social and Political Integration of Young a conceptual space with four main ideal-typical

Unemployed (YOUNEX). configurations of youth unemployment regimes. By

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

290 2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare

New challenges for the welfare state

allocating seven European countries (France, Germany, 1993; Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1993; Gallie &

Italy, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland) across Paugam, 2000; Merrien, 1996; Taylor-Gooby, 1991).

this conceptual space, we test its heuristic potential. Much of this literature has been concerned with the

In particular, we place our findings in the context of classification of welfare states and the identifica-

existing typologies of the welfare state, emphasising tion of ideal-types of welfare provisions (Bonoli,

most counter-intuitive aspects. For example, we will 1997, p. 351). Perhaps the most prominent one is

see that policies and institutional provisions in the Esping-Andersens (1990) well-known distinction of

unemployment field in Switzerland fit only partially three worlds of welfare capitalism. Aiming at

the traditional characterisation of social security in broadening the perspective with regard to traditional

this country, given their strong flexicurity orientation. classifications based only on the level of expenditure

Similarly, we argue that precariousness may well be (Cutright, 1965; Wilensky, 1975), this author focused

the distinct element of policies directed specifically at on the level of decommodification as a basis for

the unemployed youth in Germany, fitting only partially classifying the welfare state according not only to the

with the idea of an inclusive welfare state. Ultimately, amount of social provisions, but also to the ways in

we show that the way in which unemployment is insti- which they are delivered. Based on that, he distin-

tutionally thought and regulated deserves the highest guished between three types: the liberal or residual

attention, as it might be at the core of broader dynamics regime typical of the Anglo-Saxon countries, the

that question the nature of the welfare state as we think Bismarckian or insurance-based regime typical of

of it today. the continental European countries, and the univer-

The next section provides a discussion of the com- salist or social-democratic regime typical of the

parative literature on the welfare state as well as more Nordic countries.

specific studies focusing on unemployment. This dis- Similar typologies have been proposed by other

cussion will serve as a basis for presenting our typol- authors as well. All of them, in the end, rely on the

ogy of youth unemployment regimes. Then we show basic distinction between the Bismarckian and the

the methodological approach that we have followed so Beveridgean models of social policy (Castel, 1995;

as to retrieve systematic information on the two dimen- Rosanvallon, 1995); then they add further distinctions

sions of our framework. Lastly, we show how the seven to provide a more accurate picture. For example,

countries of our study locate on each of the two dimen- Ferrera (1993) distinguished between occupational

sions of youth unemployment regimes as well as and universalist welfare states based on the criterion

within the space resulting from the combination of the of coverage of social protection schemes.1 Similarly,

two dimensions. Bonoli (1997) distinguished between four ideal-typical

welfare states based on the quantity of welfare they

provide and where they stand on the Beveridgean/

Welfare state and unemployment regimes

Bismarckian dimension: Beveridgean/high-spending

Our approach of youth unemployment regimes in welfare states, Beveridgean/low-spending welfare

Europe is directly inspired from the comparative states, Bismarckian/high-spending welfare states and

literature on the welfare state (for reviews, see Arts & Bismarckian/low-spending welfare states. More

Gelissen, 2002; Green-Pedersen & Haverland, 2002; recently, scholars have discussed the transformation of

Pierson, 2000). A great deal of this literature has fol- welfare states with reference to globalisation and its

lowed two main lines of inquiry. A first line of inquiry consequences, in particular concerning trends towards

has looked at the development of the welfare state. In liberalisation (Ellison, 2006) and the new risks relating

this perspective, scholars have focused on the expan- to post-industrial society (Bonoli, 2007; Clasen &

sion of the welfare state, most notably by looking at the Clegg, 2011; Taylor-Gooby, 2004). While these new

broader societal forces and processes leading to such an risks are associated with many components of public

expansion, in particular in the post-war period (van welfare (health, pension systems, unemployment etc.),

Kersbergen, 2002). Starting from the 1990s, however, today they are especially the object of debates concern-

the focus has shifted from welfare state expansion ing the labour market and employment policies.

to its retrenchment. Scholars have therefore started Most, if not all, of the works reviewed above deal

to examine the political and institutional factors with the welfare state or social policy. As a result, they

explaining the welfare states retrenchment from a are only of limited help for studying cross-national

neo-institutionalist perspective (Pierson, 1994, 1996; differences in state intervention and policy-making

Skocpol, 1992). relating especially to unemployment. A more specific

The second, more often explored, line of inquiry is focus is thus required. This is, for example, what

more relevant for our present purpose. Here, scholars of

social policy and the welfare state have focused on 1

Ferrera (1996), among others, also stressed the existence and

cross-national variations (e.g. Bonoli, 1997; Cochrane, peculiarities of the southern model of welfare.

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare 291

Cinalli & Giugni

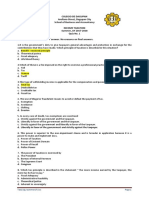

Gallie and Paugam (2000) did in their study of Unemployment regulations

unemployment-providence regimes and their impact on Exclusive Inclusive

the experience of unemployment. According to them,

Flexible

the latter may be influenced by the degree of coverage,

the level of financial compensation and the importance Precariousness Social

of active measures for employment. Based on these protection

factors, they define four such regimes: the sub- or flexsecurity

protecting regime, providing the unemployed with a

Labour market regulations

protection below the subsistence level; the liberal/

minimal regime, offering a higher level of protection,

but not covering all the unemployed and in which the

level of compensation is weak; the employment-centred

regime, offering a much higher level of protection, but

in which the coverage remains incomplete because of

the eligibility principles for compensation; and the uni-

versalist regime, characterised by the breadth of the Economic Full protection

coverage, a much higher compensation level and more protection

developed active measures. or corporatist

Rigid

Despite this and similar efforts, however, most often

than not comparative analyses of state responses to

unemployment still refer to welfare provisions in

Figure 1. Unemployment regulations versus labour market

general. Even when dealing directly with indicators of regulations.

unemployment regulations (Bambra & Eikemo, 2009),

comparative research may overlook findings that do not

fit the teaching of traditional welfare state scholarship.

As a consequence, more systematic research is needed Most crucially, unemployment regulations and

to consider specific measures aimed at creating a safety labour market regulations can be combined so as to

net for those who are or become excluded from the construct a bi-dimensional space within which each

labour market (the so-called passive measures) and at country has a specific position. Conceptually, this space

giving them more chances to become employable was initially meant to work as a typology that is useful

(the so-called active measures). As Clasen and Clegg to identify specific opportunities for collective action in

(2011, p. 1) stress: the field of unemployment politics relating to welfare

state regimes (Cinalli & Giugni, 2010; Giugni et al.,

[i]n the large comparative literature on welfare state

2009). Yet, we can also use it to highlight cross-national

development in recent decades, there are few com-

variations in the institutional approaches to unemploy-

prehensive studies of unemployment protection

ment or different unemployment regimes.

systems as a whole, and fewer still that focus explic-

Figure 1 shows the potential organisation of this

itly on the relationship between the regulation of the

space into four main ideal-types. The first type couples

risk of unemployment and labour market change.

inclusion of the unemployed with flexibility of the

Therefore, although they certainly are highly corre- labour market, representing the so-called flexicurity or

lated to the general features of the welfare state, we social protection model. The second, opposite type, the

need to take into account more specific approaches traditional corporatist or economic protection model,

to unemployment. Yet, unemployment regulations are couples exclusion of the unemployed with high protec-

only one side of the coin. The other side is formed by tion of insiders. Third, the combination of rigidity on

state intervention on the labour market, that is, labour the labour market dimension and inclusion on the

market regulations. As Esping-Andersen (1990, 1999) unemployment regulations dimensions represents the

pointed out, labour market regulations are central to an full protection model where inclusion of the outsiders is

understanding of the modern welfare state. Similarly, not negotiated against the loss of rights for protected

Sapir (2005) maintained that different types of welfare insiders. Lastly, the precariousness model couples a

state tend to have a different labour market organisa- low level of rights for traditional workers together with

tion. Thus, in order to get a more comprehensive picture the exclusion of the unemployed.

of how the state intervenes with respect to unemploy- This conceptual space is also useful to go beyond

ment, one needs to take into account not only how the the rigid kind of typologies that one usually finds in

state responds to the challenge of unemployment (both the literature, and that tend to assign countries to fixed

through passive and active measures), but also how it models. In other words, countries do not necessarily fit

regulates the labour market. rigidly a given type, but they may be placed in different

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

292 2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare

New challenges for the welfare state

positions within a same type and may travel across otherwise shaped according to a more comprehensive

space if the analysis were conducted diachronically. understanding of unemployed youth.

In the remainder of this article, however, we use Indicators were appraised following a simplified

this conceptual space to show the synchronic cross- scoring procedure allowing for cross-national compara-

national variation of youth unemployment regimes tive analyses. More specifically, for each indicator we

in Europe and, more specifically, how institutional attributed a score of +1, 0 or -1: +1 indicates a strong

approaches to unemployment vary across countries degree of inclusiveness of unemployment regulations

along our two dimensions. Before doing so, we need along the first dimension or otherwise a strong degree

to say more about the empirical basis of our study and of flexibility of labour market regulations along the

the specific way in which we have operationalised the second dimension; minus 1 indicates a low degree of

two dimensions. inclusiveness of unemployment regulations or other-

wise a low degree of flexibility of labour market regu-

lations; and 0 indicates an intermediate situation. The

Data retrieval

average scores on the whole set of indicators for each

Our mapping of youth unemployment regimes in dimension then give us the position of countries with

Europe is based on systematic information on existing respect to the two dimensions of the typology. Overall,

policies and measures in the field of unemployment 16 indicators were used to grasp the two dimensions of

politics retrieved as part of the EU-funded project youth unemployment regimes. The dimension of unem-

Youth, Unemployment, and Exclusion in Europe: A ployment regulations refers to the conditions of access

Multidimensional Approach to Understanding the to rights and welfare provisions for the unemployed, but

Conditions and Prospects for Social and Political also to the obligations attached to full enjoyment of

Integration of Young Unemployed (YOUNEX). The rights and provisions. In particular, the average score

two dimensions that form our definition of youth unem- for this first dimension is based on eight indicators: the

ployment regimes have been operationalised by means formal prerequisites for obtaining social provision, the

of a set of indicators of policies and measures concern- level of coverage, the extension of coverage, the shift-

ing unemployment regulations and labour market regu- ing to social aid, the role played by private and public

lations that target the unemployed youth, including employment agencies, the sanctions for abusing the

individuals aged 1834. We are aware that official sta- unemployment system, and (as output indicators) the

tistics on youth unemployment for example those that number of people receiving unemployment benefits,

are produced by the central governments of our coun- and lastly, the number of people receiving sanctions for

tries, as well as Eurostat, the International Labour abusing the benefit system. The dimension of labour

Organisation and so forth refer specifically to the market regulations acknowledges that rights and obli-

cohort of young people aged less than 25. However, we gations deriving from unemployment legislation and,

have decided to be more inclusive in terms of age more generally, from state welfare, can go hand in hand

(1834) so as to take into account ongoing social pro- with labour market arrangements, as the example of

cesses that have substantially augmented the time span active measures shows. It is also important to assess the

that individuals have to wait for before entering a full existence of a clear distinction between protected

adult life (Billari, 2004). This decision also follows workers and unemployed, or otherwise the insiders and

from the fact that our study includes countries where the outsiders, as a consequence of the types of labour

this lengthening of youth is remarkable owing to market regulations (Berger & Piore, 1980; Lindbeck &

changes in terms of family situation, living conditions, Snower, 1988; Rueda, 2005). The average score for this

health and education (Eurostat, 2009). second dimension is also based on eight indicators:

We have thus formulated our lists of indicators so as protection of the insiders against dismissals, regulation

to include relevant information for unemployed young of temporary forms of work, requirements for collec-

people who are aged 1834. Yet, for the same indica- tive dismissals, role of unions in the benefits system,

tors, we have also distinguished information referring role of unions for protection of workers, and (as output

specifically to the cohort of younger unemployed indicators) the number of temporary workers, number

people who are under 25. This information is not of flexible workers, and lastly, number of participants in

always relevant as often there is hardly any difference activation measures.

between regulations targeting the very young unem- In particular, the two main steps of our research have

ployed and those targeting our broader population of consisted in the collection of information so as to

unemployed youth aged 1834. Nevertheless, we describe each case across the selected indicators and in

thought that it was crucial to assess more systematically the standardisation of information along the continuum

the extent to which unemployment regulations and -1 to +1 for comparative purposes. The first qualitative

labour market regulations take into account the specific step has thus provided the basis on which the second

needs and situation of the younger group, or are quantitative step has been accomplished, allowing for

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare 293

Cinalli & Giugni

Exclusive Inclusive

Flexible

Labour market regulations

Rigid

Unemployment regulations

Figure 2. Location of countries within the conceptual space of unemployment regimes.

translation of each indicator into an interval measure with crucial policies to loosen up the labour market

along the 3-point scale. We have already indicated that while fostering the rights and interests of the unem-

our information refers to legislation and policy-making, ployed such as the Hartz reform (e.g., Fleckenstein,

but also includes output indicators so as to understand 2008). Most recently, in the aftermath of the economic

softer informal aspects for each dimension. In so doing, recession of the late 2000s, the political future of a large

we aim to find out the effect of constraints that may be number of national governments has been linked to

operating behind formal regulations. For example, we their interventions in the unemployment field. Beyond

consider the number of people who are engaged in the trajectories of specific national executives, the

flexible forms of contracts to be very useful to indicate European Union adopted the European Youth Pact in

the true flexibilisation of access to the labour market for 2005 and put the Employment Guidelines at the centre

the unemployed youth. All scores refer to the 2008 of its European Employment Strategy. Both the Com-

2010 period. The scoring rules for each indicator are mission and the Council have felt the need to intensify

shown in the Appendix.2 their strategy for fostering inclusion of the unemployed

and, more broadly, of young disadvantaged people.

Interventions such as the EU Strategy for Youth,

Youth unemployment regimes in Europe: the Council Resolution on a renewed framework for

an empirical assessment European cooperation in the youth field (20102018)

The 2000s have been characterised by the implementa- and the Agenda 2020 provide substantial evidence of a

tion of an increasing number of policies tackling unem- comprehensive policy effort that is cross-sectoral and

ployment, and young unemployment in particular. Even highly articulated.

the most progressive forms of leftist liberalism, such as This mixture of common efforts at the European

the RedGreen coalition in Germany, have engaged level and specific national interventions in terms of

labour market and unemployment regulations targeting

2

the unemployed youth can be appreciated through the

The specific sources used for retrieving the information are analysis of our findings in Figure 2. Each of the seven

indicated in the integrated report on the part of the research

dealing with the institutional indicators (YOUNEX, 2008). countries is given an average score for unemployment

However, it should be noted that, after the report was written regulations and labour market regulations across the

and delivered, we updated and slightly modified some of the indicators that have been mentioned earlier. Consider-

indicators, so that our findings do not fully reflect the content ing each dimension separately, the data show that

of that report. Additional information was provided by the

members of the YOUNEX research team, which we warmly cross-national variations are especially wide-ranging in

thank. terms of unemployment regulations. Some countries

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

294 2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare

New challenges for the welfare state

implement highly inclusive policies vis--vis the young Italy and Portugal are the two cases that come closest

unemployed, while others stand out for their much more to the economic protection model. Finally, the position

exclusive stance. The difference is particularly large, of Germany is somewhat surprising given the same

for example, when one compares France with Poland. embodiment of the country with the Bismarckian

More generally, one can argue that countries tend to model. Our findings show that Germany has policies

choose clearly between a more inclusive and a less that are in line with flexibility in the labour market, but

inclusive approach. By contrast, cross-national varia- it has poor unemployment regulations for the inclusion

tions are not that strong when focusing on the dimen- of the unemployed youth. Germany thus fits with the

sion of labour market regulations. In this case, the range precariousness model, which does little for the insiders

between the most flexible approach of Sweden and the while giving little to the outsiders.

most rigid cases of Italy and Portugal is overall con- Having focused on distinct approaches targeting

tained. More generally, one can argue that between the unemployed youth across Europe, it is important to

two poles of rigidity and flexibility, this latter is the come back to our distinction between young and

most likely option across the European countries. younger unemployed people so as to assess the extent to

Overall, then, the analysis of unemployment regula- which policies and institutional provisions target spe-

tions shows that a large gulf exists between countries cifically the youngest cohort.4 Our findings are quite

that exclude the unemployed youth, on the one hand, conclusive, owing to the overall lack of specific policies

and countries that are highly inclusive, on the other. for the younger across our countries. It should be said,

Variations along the second dimension of labour market however, that most flexible labour market regulations

regulations are relevant, but much smaller. Italy and are sometimes especially relevant for the younger even

Portugal stand out as the only cases that have not made in the absence of de jure distinctions. Thus, Sweden and

a clear break into flexibility.3 Switzerland, that is, the most flexible countries in our

Our findings also suggest that flexibility in the study, stand out as the places where people aged 1824

labour market does not necessarily involve more inclu- are especially present in fixed and part-time forms

sion of the unemployed youth on the dimension of of working conditions. In Sweden, 47 per cent of

unemployment regulations, as the cases in Poland and employed young people under 25 were recruited in

Germany. In other words, the position of a country can part-time contracts in 2010, while at the same time

be very similar but also very dissimilar across the two there were just over 26 per cent of people working part

dimensions of unemployment and labour market regu- time out of the total national workforce (Labour Force

lations. This means that no relevant correlation exists Survey, 2010). In Switzerland, 27 per cent of the active

between the policy choices that countries implement population under 25 were employed in 2008 under

along the two dimensions. various forms of fixed-term contracts, 41 per cent of

Looking now at the place of our seven countries which consisted of precarious youth on-call work

within the conceptual space discussed earlier, it is first (ESPA, 2008). One should also notice that the further

noticeable that no case fits with the full protection de facto flexibilisation of young people aged 1824 in

model. France stands out as the national case that is Sweden and Switzerland does not imply further de jure

somewhat closer to this ideal-type as it has focused its inclusiveness alongside the dimension of unemploy-

own policies relatively more on the inclusion of the ment regulations. Thus, the younger face overall the

unemployed youth than on the flexibilisation of the same provisions existing for the older unemployed. In

labour market. Sweden and Switzerland show their fact, minor differences exist so as to restrict, rather than

flexibility in terms of the labour market while at the foster, the inclusion of young unemployed people under

same time targeting the unemployed youth with inclu- 25. In Sweden, the younger lose the right to unemploy-

sive measures, hence standing out as the best cases ment benefits as soon as refusing an offer of activation

fitting the social protection model. By contrast, institu- measure (the same refusal is sanctioned only with a

tional provisions and policies in Italy and Portugal do reduction of benefits in the case of young unemployed

not fit the flexicurity model. Traditional corporatist aged 2534), whereas in Switzerland students and

arrangements (that grant extensive rights to the insiders apprentices, as well as young people under 25 who have

of the labour market) are still at work in Italy and no training (completed or underway), cannot receive

Portugal, while at the same time both countries have regular benefits. Overall, then, Sweden and Switzerland

few inclusive policies vis--vis the outsiders (and the confirm their flexicurity approach to youth unemploy-

mid-siders; see Jessoula et al., 2010). Overall, then, ment across the 1834 range, though with an extra bite

3

In addition, and beyond the synchronic dimension of our

4

research, one may consider relevant diachronic movements of Much of the information we use for this assessment of recent

Italy and Portugal towards flexibility (Jessoula, Graziano, & political reforms was provided by members of the YOUNEX

Madama, 2010; see also Baglioni in this issue). consortium. We thank them for their help.

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare 295

Cinalli & Giugni

of flexibility for the younger, owing to the demographic

Conclusion

characteristics in the labour market.

France also confirms its position within the flexicu- This article has inquired into a number of indicators

rity camp when focusing on policies targeting specifi- along the two dimensions of unemployment regulations

cally the younger unemployed. An extra bite of de and labour market regulations so as to discuss variable

facto inclusiveness, however, can be observed. Thus, configurations of youth unemployment regimes. We

44 per cent of unemployed people under 25 receive have considered not only formal laws and policy-

benefits from the unemployment insurance, which is a making, but also output indicators so as to identify

large percentage when one compares them with the constraints and facilitation that might be hiding behind

55 per cent of unemployed people who obtain benefits formal regulations. Our main thrust was the construc-

from all age categories (Ple Emploi, 2011). One could tion of a conceptual space allowing for identifying

also mention that, since 2010, the shift from unemploy- cross-national variations in Europe and the empirical

ment to social aid has become more inclusive also for assessment of the position of seven European countries

the younger through the extension of the Revenu de within this space. Our findings enable us to enter the

Solidarit Active for the unemployed youth aged 25 or scholarly discussion of results from other typologies in

less. That is, findings for the youngest cohort of the the comparative literature on the welfare state (e.g.,

unemployed open up space for further research on Bonoli, 1997; Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1993;

the potential distinction within the flexicurity camp Gallie & Paugam, 2000). In this regard, we have

between countries that might put extra efforts on observed consistencies as well as unexpected findings.

flexibility (such as Sweden and Switzerland) on the one The two southern European countries as well as Poland

hand, and countries that focus on further inclusion reflect the characterisation of their unemployment

(such as France) on the other hand. regimes as being sub-protective (Gallie & Paugam,

Germany and Poland confirm their position within 2000). France and Sweden stand out as being very

the precariousness camp when focusing on policies generous in terms of unemployment regulations, but

for the young unemployed under 25. In fact, findings they have quite flexible labour market regulations

for the Polish case show that no relevant distinction is pushing them towards the flexicurity model. As regards

made, at least along the two dimensions of unemploy- Switzerland, it does not fit the liberal/minimal regime

ment regulations and labour market regulations, in (Bertozzi, Bonoli, & Gay-des-Combes, 2005). Its high

terms of specific provisions for the younger vis--vis flexibility in terms of the labour market is not coupled

the older unemployed. As regards Germany, its poli- with restrictive conditions for the unemployed, but

cies of exclusion in terms of unemployment regula- rather with high unemployment compensations

tions are also common for the younger. The latter, and relatively favourable conditions for the low-skill

when not eligible for insurance-based benefits and precarious group (Bonoli & Mach, 2001).

not married, are supposed to live with their parents. Most crucially, our conceptualisation is also valu-

Benefits can thus be granted only if family support is able to identify variations that are hardly discussed in

not possible (while the option to live alone is possible the extant literature, discussing cross-national differ-

only if the labour agency agrees that there are good ences that do not fully fit the traditional teaching of

reasons to move out). At the same time, restrictive comparative welfare studies. The case of Germany,

policies are confirmed in terms of labour market regu- in particular, has been singled out. Our findings go

lations, owing to the high percentage of flexible against the idea of a Bismarckian state par excellence

employees among the younger as well as the high as Germany is characterised by high flexibility in

number of young people under 25 in active labour terms of labour market regulations. Indeed, there have

market policies. been considerable changes going on in Germany

Lastly, we have found that policies for the younger fit owing to the Hartz Reform, which was passed as a

broader patterns of youth unemployment regimes also series of laws between 2003 and 2005 (Kemmerling &

in Italy and Portugal. The Italian fit is remarkable, Bruttel, 2006). While there is much dispute about

owing to the very restrictive approach of Italy in terms whether this is a break with the past or rather a gradual

of unemployment benefits (regardless of different age and incremental change of policy orientations follow-

categories) and to the fact that flexibilisation of the ing development of government policies since the

labour market is particularly intense with regard to the early 1980s, the main point of our findings is that the

project-related fixed-term contract in the 2534 cohort. Bismarckian model is hardly a model for the descend-

As regards Portugal, one finds that the young unem- ants of Bismarck themselves. In fact, precariousness is

ployed under 25 are not more likely to benefit from the the distinct element of Germany in its approach to the

unemployment insurance, with flexible forms of work unemployed youth. At the same time, the Bismarckian

such as part timing being quite balanced across model is not working for other European countries.

different age cohorts of workers. Our findings show that France that is, the best buddy

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

296 2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare

New challenges for the welfare state

of Germany in traditional accounts of comparative impacted upon specific provisions dealing with unem-

welfare studies is actually far from Germany in our ployment. Accordingly, we have analysed systemati-

bi-dimensional space, as well as from the ideal-type of cally not only information referring to our broad

the corporatist model. definition of unemployed youth (1834), but also infor-

In addition, our findings allow for reflecting upon mation specifically relevant for the cohort of younger

similar patterns across European countries, at least the unemployed under 25. In so doing, we wanted to evalu-

ones considered here. We have shown some important ate whether our youth unemployment regimes work

similarities in terms of flexible labour market regula- across the age cleavage that is often suggested by

tions. In particular, our data show that a common pref- official statistics. The answer has been overall positive.

erence for flexibilisation of the labour market exists Young people over 25 are the target of crucial provi-

regardless of cross-national distinctions. Thus, flexibil- sions at least as much as the unemployed youth aged

ity has been placed high on the political agenda in under 25. Even when the latter are taken at the core of

traditionally insurance-based welfare regimes such as the analysis of unemployment and labour market regu-

France and Germany, as well as in traditionally uni- lations, one finds that institutional arrangements and

versalist or social democratic regimes such as Sweden. policy-making have not a distinct shape according to

More generally, we have observed a sort of alignment the specific situation of the youngest cohort, but usually

of all the countries in our study along the dimension of reinforce youth unemployment regimes. Yet, we have

labour market regulations (towards a relatively high found that the distinction between young and younger

level of flexibility). At least in the view of a certain is still useful to open space for further research

political part, the counterpart of this strong flexibili- into differences within a same corner of our bi-

sation of the labour market is an increased precarious- dimensional space. In particular, we have shown that

ness of workers and in some case what some have the flexicurity type can put more emphasis on the

called flex-insecurity (Berton, Richiardi, & Sacchi, flexible side of labour market regulations (e.g., in

2009). Yet, we have also emphasised that cross- Sweden and even more so in Switzerland) or alter-

national variations are still most likely in terms of natively on the inclusive side of unemployment

unemployment regulations. regulations (e.g. in France).

Lastly, we have shown the need to extend the age

borders of too strict a definition of youth unemploy-

Acknowledgement

ment so as to include young unemployed people up

to their early 30s. Not only have social processes This project was funded by the European Commission

increased the time span that individuals have to wait under the 7th Framework Programme (Grant Agree-

before entering a full adult life, but they have also ment no. 216122).

Appendix

Unemployment Regulations

Indicator Information to be found Final Data

1 Formal pre-requisites for obtaining social Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

provisions (-1 = FT workers only with long periods of contributions;

(conditions to obtain insurance compensations) 0 = inclusive with benefits linked to contributions but open to mothers, students etc.;

+1 = universal with no requirements)

2 Level of coverage Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(amount compared with the minimum/average (-1 = little amount and short duration; 0 = little amount combined with long duration

salary + duration) or vice versa; +1 = substantial amount for a long duration)

3 Extension of coverage Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(who is insured or compensated) (-1 = insider workers in a male breadwinner fashion; 0 = open to outsiders but with

restrictions; +1 = completely open to non-standardised workers, youth and women

returning to the labour market)

4 Shifting to social aid Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(means-testing and amount) (-1 = uneasy shift, means-tested and poor benefits;

0 = combinations means tested/rich amount or universal/poor amount;+1 = easy

shifting with rich amounts)

5 Role played by private and public employment Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

agencies (number/duration/collaboration; attempt to combine the three elements: -1 = 0 =

(combinations of number of people using these +1=)

services and duration of their unemployment)

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare 297

Cinalli & Giugni

Indicator Information to be found Final Data

6 Counter-provisions and sanctions Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(length, intensity) (-1 = strong and long sanctions; 0 = combination of strength without length and vice

versa; +1 = short and light sanctions)

7 People receiving unemployment benefits Absolute figure + Percentage on the total number of registered unemployed

(-1 = less than . . . ; 0 = between . . . ; +1 = more than . . .)

8 People receiving sanctions for abusing the Absolute figure + Percentage on the total number of abusing cases

benefits system (-1 = less than . . . ; 0 = between . . . ; +1 = more than . . .)

Labour Market Regulations

Indicator Information to be found Final data

9 Protection of permanent workers against Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

dismissals (focusing on easy/difficult conditions and high/low compensations relative to salary;

3-point scale built upon OECD data)

10 Regulation on temporary forms of employment Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(-1 = highly regulated; 0 = some regulation; +1 = scarcely regulated; 3-points scale

built upon OECD data)

11 Specific requirements for collective dismissal Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale(-1 = many requirements;

0 = some role; +1 = few requirements; 3-points scale built upon OECD data)

12 Temporary work Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(-1 = very limited; 0 = some role; +1 = well developed)

13 Role of unions in the benefit system Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(-1 = no role; 0 = some co-sharing responsibilities with other actors; +1 = extensive

responsibilities)

14 Unions protection of workers Max. 1-page report + comparative 3-point scale

(-1 = scarce protection for full-time workers; 0 = extensive protection of full-time

workers; +1 = protection all workers, both insiders and outsiders)

15 Flexible workers Absolute figure + Percentage of fixed term contracts on total contracts and by age

(-1 = less than . . . ; 0 = between . . . ; +1 = more than . . .)

16 Participants in activation measures Looking at figures such as percentages of participants compared with the labour force

and all of the unemployed (caution: participants in activation measures are not

considered unemployed in some countries; if so, add the number of participants to

the number of unemployed to get the reference category)

(-1 = less than . . . ; 0 = between . . . ; +1 = more than . . . ; 3-point scale compiled

upon OECD data combining public expenditure and participant stocks-training, job

rotation and job sharing, employment incentives, supported employment and

rehabilitation, direct job creation, start-up incentives)

References Bonoli, G. (1997). Classifying welfare states: A two-dimension

approach. Journal of Social Policy, 26, 351372.

Arts, W. & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three worlds of welfare capital- Bonoli, G. (2007). Time matters: Postindustrialisation, new social

ism or more? A state-of-the-art report. Journal of European risks and welfare state adaptation in advanced industrial

Social Policy, 12, 137158. democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 40, 495520.

Bambra, C. & Eikemo, T. A. (2009). Welfare state regimes, Bonoli, G. & Mach, A. (2001). The new Swiss employment

unemployment and health: A comparative study of the rela- puzzle. Swiss Political Science Review, 7, 8194.

tionship between unemployment and self-reported health in Bonoli, G. & Palier, B. (2001). How do welfare state change?

23 European countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Com- Institutions and their impact on the politics of welfare state

munity Health, 63, 9298. reform in Western Europe. In: S. Leibfrield (Ed.), Welfare

Berger, S. & Piore, M. (1980). Dualism and discontinuity in state futures (pp. 5776). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

industrial societies. New York: Cambridge University Press. versity Press.

Berton, F., Richiardi, M., & Sacchi, S. (2009). Flex-insecurity: Castel, R. (1995). Les mtamorphoses de la question sociale.

Perch in Italia la flessibilit diventa precariet [Flex- Paris, France: Fayard.

insecurity: Why in Italy flexibility becomes precariousness]. Cinalli, M. & Giugni, M. (2010). Welfare states, political oppor-

Bologna, Italy: Il Mulino. tunities, and the claim-making in the field of unemployment

Bertozzi, F., Bonoli, G., & Gay-des-Combes, B. (2005). La politics. In: M. Giugni (Ed.), The contentious politics of

rforme de ltat social en Suisse: Vieillissement, emploi, unemployment in Europe: Welfare states and political oppor-

conflit travail-famille [The reform of welfare state in tunities (pp. 1942). Houdmills, UK: Palgrave.

Switzerland: Ageing, employment, conflict workfamily]. Clasen, J. & Clegg, D. (2011). Unemployment protection and

Lausanne, Switzerland: Presses polytechniques et universi- labour market change in Europe: Towards triple integration.

taires romandes. In: J. Clasen & D. Clegg (Eds.), Regulating the risk of unem-

Billari, F. (2004). Becoming an adult in Europe: A macro(/ ployment: National adaptations to post-industrial labour

micro)-demographic perspective. Demographic Research, 3, markets in Europe (pp. 112). Oxford, UK: Oxford Univer-

1544. sity Press.

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

298 2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare

New challenges for the welfare state

Cochrane, A. (1993). Comparative approaches and social policy. van Kersbergen, K. (2002). Comparative politics and the welfare

In: A. Cochrane & J. Clarke (Eds.), Comparing welfare state. In: H. Keman (Ed.), Comparative democratic politics

states: Britain in international context (pp. 118). London: (pp. 185212). London, UK: Sage.

Milton Keynes, Sage/Open University. Labour Force Survey. (2010). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved from

Cutright, P. (1965). Political structure, economic development, http://www.ssd.scb.se/databaser/makro/MainTable.asp?yp=

and national social security programs. American Journal of tansss&xu=C9233001&omradekod=AM&omradetext=

Sociology, 70, 537550. Labour+market&lang=2&langdb=2 [last accessed 4 July

Ellison, N. (2006). The transformation of welfare states? 2012].

London: Routledge. Lindbeck, A. & Snower, D. (1988). The insider-outsider theory

ESPA. (2008). Enqute sur la population active 2008 Suisse of employment and unemployment. Cambridge, MA: MIT

(Survey on Active Population 2008 Switzerland). Press.

Retrieved from http://www.ge.ch/statistique/domaines/03/ Merrien, F.-X. (1996). tatprovidence et lutte contre

03_03/tableaux.asp#2 [last accessed 4 July 2012]. lexclusion [Welfare state and fight against exclusion]. In: S.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capi- Paugam (Ed.), LExclusion, ltat des savoirs [Welfare state

talism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. and fight against exclusion] (pp. 417427). Paris, France: La

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindus- Dcouverte.

trial economies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Pierson, P. (1994). Dismantling the welfare state? Reagan,

Eurostat. (2009). Youth in Europe: A statistical portrait. Luxem- Thatcher and the politics of retrenchment. Cambridge, UK:

bourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Cambridge University Press.

Ferrera, M. (1993). Modelli di solidariet [Models of solidarity]. Pierson, P. (1996). The new politics of the welfare state. World

Bologna, Italy: Il Mulino. Politics, 49, 143179.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The southern model of welfare in social Pierson, P. (2000). Three worlds of welfare research. Compara-

Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6, 1737. tive Political Studies, 33, 791821.

Fleckenstein, T. (2008). Restructuring welfare for the unem- Ple Emploi. (2011). Dares, Statistiques du march du travail

ployed: The Hartz legislation in Germany. Journal of Euro- [Dares, statistics of the labour market]. Retrieved from

pean Social Policy, 18(2), 177188. http://www.travail-emploi-sante.gouv.fr/etudes-recherche-

Gallie, D. & Paugam, S. (Eds.) (2000). Welfare regimes and the statistiques-de,76/statistiques,78/chomage,79

experience of unemployment in Europe. Oxford, UK: Oxford Rosanvallon, P. (1995). La nouvelle question sociale [The new

University Press. social question]. Paris, France: Seuil.

Giugni, M., Berclaz, M., & Fglister, K. (2009). Welfare states, Rueda, D. (2005). Insideroutsider politics in industrialized

labour markets, and the political opportunities for collective democracies: The challenge to social democratic parties.

action in the field of unemployment: A theoretical frame- American Political Science Review, 99, 6174.

work. In: M. Giugni (Ed.), The politics of unemployment in Sapir, A. (2005). Globalisation and the Reform of European

Europe: State and civil society responses (pp. 133149). Social Models. Brussels, Bruegel. Retrieved from http://

Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. www.bruegel.org

Green-Pedersen, C. & Haverland, M. (2002). The new politics Skocpol, T. (1992). Protecting soldiers and mothers. Cambridge,

and scholarship of the welfare state. Journal of European MA: Harvard University Press.

Social Policy, 12, 4351. Taylor-Gooby, P. (1991). Welfare state regimes and citizenship.

Jessoula, M., Graziano, P., & Madama, I. (2010). Selective flexi- European Journal of Social Policy, 1, 93105.

curity in segmented labour markets: The case of Italian mid- Taylor-Gooby, P. (Ed.) (2004). New risks, new welfare? Oxford,

siders. Journal of Social Policy, 39(4), 561583. UK: Oxford University Press.

Kemmerling, A. & Bruttel, O. (2006). New politics in German Wilensky, H. (1975). The welfare state and equality. Berkeley,

labour market policy? The implications of the recent Hartz CA: University of California Press.

reforms for the German welfare state. West European Poli- YOUNEX. (2008). Integrated Report on Institutional Analysis.

tics, 29, 90112. Retrieved from http://www.younex.unige.ch

Int J Soc Welfare 2013: 22: 290299

2013 The Author(s). International Journal of Social Welfare 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare 299

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Location AssessmentDocument8 paginiLocation Assessmentmarnil alfornonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who Are The BritishDocument2 paginiWho Are The BritishEveNedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consortium Helps Sector Face Challenging TimesDocument4 paginiConsortium Helps Sector Face Challenging TimesImprovingSupportÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRM2020-346 Decision and DocumentsDocument71 paginiCRM2020-346 Decision and DocumentspaulfarrellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physiotherapy Home Visit Service in MumbaiDocument3 paginiPhysiotherapy Home Visit Service in MumbaiDr. Krishna N. SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FAA Form 8500-7 Exp 10.31.24Document4 paginiFAA Form 8500-7 Exp 10.31.24Michael coffeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modul Kelas X Kd. 3.6-4.6Document8 paginiModul Kelas X Kd. 3.6-4.6hellennoviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sse 114Document13 paginiSse 114Jude Vincent MacalosÎncă nu există evaluări

- HahaDocument2 paginiHahaMiguel Magnö ɪɪ100% (2)

- Arnault vs. Balagtas DigestDocument3 paginiArnault vs. Balagtas DigestRany Santos100% (1)

- Cop City Signature RulingDocument32 paginiCop City Signature RulingJonathan RaymondÎncă nu există evaluări

- AP Module 2021Document79 paginiAP Module 2021Cherry Lynn NorcioÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Francisco Delos Santos 87 Phil 721Document2 paginiPeople Vs Francisco Delos Santos 87 Phil 721Mae BrionesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stages of Public PolicyDocument1 paginăStages of Public PolicySuniel ChhetriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revenue Recovery Act, 1890Document6 paginiRevenue Recovery Act, 1890Haseeb HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Responsive Documents: CREW: DOJ: Regarding Criminal Investigation of John Ensign - 8/4/2014 (Groups 13-18)Document265 paginiResponsive Documents: CREW: DOJ: Regarding Criminal Investigation of John Ensign - 8/4/2014 (Groups 13-18)CREWÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petition: in The Matter of The Guardianship of The Minors XXX PetitionDocument4 paginiPetition: in The Matter of The Guardianship of The Minors XXX PetitionNelle Bulos-VenusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lowe v. Tramont Corporation Et Al - Document No. 3Document3 paginiLowe v. Tramont Corporation Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Pages From British Socialist Fiction, 1884-1914Document14 paginiSample Pages From British Socialist Fiction, 1884-1914Pickering and ChattoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Province of Zamboanga Del Norte v. City of Zamboanga SNMCDocument3 paginiProvince of Zamboanga Del Norte v. City of Zamboanga SNMCCamille CalvoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 5: Being Part of Asean - Practice Test 1Document4 paginiUnit 5: Being Part of Asean - Practice Test 1Nam0% (1)

- SFFA v. Harvard Government Cert Stage BriefDocument27 paginiSFFA v. Harvard Government Cert Stage BriefWashington Free BeaconÎncă nu există evaluări

- Government of Goa Directorate of Official Language Panaji - GoaDocument56 paginiGovernment of Goa Directorate of Official Language Panaji - GoaEdwin D'SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Davis v. Kirkpatrick & Lockhart L.L.P. - Document No. 11Document12 paginiDavis v. Kirkpatrick & Lockhart L.L.P. - Document No. 11Justia.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improving The Efficiency of The Public SectorDocument22 paginiImproving The Efficiency of The Public SectorHamdy AbdullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sambajon Vs Suing A.C. No. 7062Document2 paginiSambajon Vs Suing A.C. No. 7062CeresjudicataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tax1 Q1 Summer 17Document3 paginiTax1 Q1 Summer 17Sheena CalderonÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPC Notes.Document43 paginiCPC Notes.Goutam ChakrabortyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agreement On Custody and SupportDocument4 paginiAgreement On Custody and SupportPrime Antonio Ramos100% (4)

- A Most Audacious Young ManDocument42 paginiA Most Audacious Young ManShisei-Do Publictions100% (4)