Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Gullen Barre

Încărcat de

Jose LuisDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Gullen Barre

Încărcat de

Jose LuisDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Guillain-Barr Syndrome

Beth A. Rosen

Pediatrics in Review 2012;33;164

DOI: 10.1542/pir.33-4-164

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/33/4/164

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2012 by the American Academy of

Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0191-9601.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

Article neurologic disorders

Guillain-Barre Syndrome

Beth A. Rosen, MD*

Educational Gap

The American Academy of Neurology published a practice parameter in 2003 outlining

Author Disclosure treatment recommendations for Guillain-Barre syndrome. The recommendations were

Dr Rosen has disclosed based on strong data in adults and were extrapolated to children because no well-designed

no financial randomized studies have been done in children.

relationships relevant

to this article. This

Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to:

commentary does not

contain a discussion of 1. Understand the common causes of acute weakness and paralysis in children.

an unapproved/ 2. Understand the presenting features of Guillain-Barre syndrome in children.

investigative use of 3. Understand how to rule out other potentially dangerous and treatable causes of

a commercial product/ weakness and paralysis in children.

device. 4. Understand the management of the child with Guillain-Barre syndrome.

Definition

Guillain-Barr syndrome (GBS) is an acquired disorder of the peripheral nerves, described

best as a polyradiculoneuropathy. With the widespread eradication of poliomyelitis, GBS is

the most common cause of acute and subacute accid paralysis in infants and children. The

disorder is characterized by progressive, symmetrical, usually ascending weakness, and di-

minished or absent reexes. Diffuse pain also is a common presenting feature in many chil-

dren with GBS, at times delaying accurate diagnosis. GBS was thought previously to be an

inammatory disorder that affected only the myelin sheath, resulting in diffuse demyelin-

ation. However, it is now recognized that the process can also attack the axon, leading to

degeneration of the nerve itself.

Epidemiology

GBS occurs year round and in all age groups. Adults are affected more commonly than

children. Some studies suggest that males are more likely to be affected than females.

The overall incidence has been estimated to range from 0.4 to 2.4 cases per 100,000

per year, with 3,500 new cases per year occurring in the United States. The incidence

in children is lower, with estimates between 0.4 and 1.3 cases per 100,000 per year.

GBS can occur at any age but is rare in children under

the age of 2 years.

Abbreviations Pathogenesis

AIDP: acute inammatory demyelinating GBS was long considered a single disorder, acute inamma-

polyneuropathy tory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP), in

AMAN: acute motor axonal neuropathy which the target is the myelin sheath. This variant of GBS

AMSAN: acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy remains the most common form seen in the United States

CSF: cerebrospinal uid and Europe. However, it has become clear that there are

GBS: Guillain-Barr syndrome phenotypically similar disorders, acute motor axonal neurop-

IgG: immunoglobulin G athy (AMAN) and acute motor and sensory axonal neurop-

IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin athy (AMSAN), in which the target is the axon itself, rather

MFS: Miller-Fisher syndrome than the myelin sheath. AMAN is the predominant form

seen in children in China and South America. In addition

*Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA; Pediatric Neurologist, Baystate Childrens

Hospital, Springfield, MA.

164 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

neurologic disorders guillain-barre syndrome

there are other variants considered to fall under the cat- innervate the extraocular muscles are enriched with

egory of GBS, the most common of which is the Miller- G1QB ganglioside, which explains why ophthalmoplegia

Fisher syndrome (MFS), a disorder characterized by is the hallmark of this disorder.

ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areexia, usually with little

to no weakness. Clinical Aspects

The pathogenesis of GBS is believed to be an abnor- GBS is a triphasic illness characterized by an acute phase,

mal immune response to an antecedent event, most com- a plateau phase of variable length, and a recovery phase

monly an infection. Approximately two-thirds of patients that can take weeks to months. Initial symptoms usually

report a respiratory or gastrointestinal illness in the weeks present between 1 and 4 weeks after a respiratory or di-

preceding onset of symptoms. Many viruses and bacteria arrheal illness.

have been implicated, including cytomegalovirus, Epstein- The rst phase is characterized by the onset and pro-

Barr virus, Haemophilus inuenzae, herpes simplex virus, gression of symptoms. This phase can last from hours to

and Mycoplasma. The strongest association is with the weeks. The usual presenting concern is weakness that

bacterium Campylobacter jejuni, which is believed to may manifest as a disturbance of gait such as refusal to

be the cause of 20% to 30% of GBS in the United States walk, walking on a wide base, or difculty with running

and Europe and a higher percentage of the AMAN cases or climbing stairs. The gait disturbance, although usually

seen in China and South America. interpreted initially to be ataxia and therefore thought to

Vaccines also have been implicated as a triggering fac- represent central nervous system disease, usually is caused

tor. Some evidence suggests that the swine u vaccine by weakness rather than cerebellar dysfunction. Vague

used in the 1976 inuenza season led to an increased in- paresthesias often are described. Signicant, poorly local-

cidence of GBS. There are no data linking other vaccines, ized pain is common, which can cause delay in diagnosis,

including diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis and because the child may be difcult to examine; early nd-

measles-mumps-rubella, to GBS. In 2005, the Food ings may be subtle, and pain is not commonly known to

and Drug Administration issued an advisory about the be associated with GBS.

possible association between the MCV4 meningococcal As is typical in a peripheral neuropathy, weakness usu-

vaccine and GBS and recommended that the vaccine ally begins distally in the legs and ascends, at times rapidly,

not be given to adolescents or adults with a history of to involve the arms, face, and muscles of respiration. The

GBS. However, the 2009 Red Book published by the weakness usually is accompanied by diminished or absent

American Academy of Pediatrics says the available data reexes early in the course. Less commonly, weakness be-

cannot determine with certainty whether MCV4 in- gins in the proximal muscles, a pattern that can lead to an

creases the risk for GBS and do not affect immunization incorrect diagnosis of myositis. Cranial nerve abnormalities

recommendations. (1) are frequent, occurring in up to 50% of patients in some

Rarely, GBS can be the presenting manifestation of case studies. The facial nerve is the most commonly af-

lymphoma or systemic lupus erythematosus or can deve- fected cranial nerve, and the weakness often is bilateral.

lop during the course of lymphoma or systemic lupus. Papilledema is a rarely reported nding in GBS and repre-

sents increased intracranial pressure of unclear etiology.

Pathophysiology Pupillary abnormalities are rare and should lead to consid-

The pathophysiology of GBS is not completely under- eration of another diagnosis, such as botulism.

stood. Both cellular and immune functions are involved. Autonomic instability, including cardiac dysrhythmias,

It is believed that, in a type of molecular mimicry, anti- orthostatic hypotension, hypertension, paralytic ileus, and

bodies that form in response to antigens on the causative transient bladder dysfunction, is common and can occur

agent, usually a bacterium or virus, cross-react with gan- anytime during the illness. Patients must be monitored

gliosides on the surface of the peripheral nerve. Antiganglio- closely for autonomic instability because it can be life

side antibodies, most commonly GM1, occur frequently in threatening.

GBS. Some appear to target the myelin sheath, others, The acute illness usually peaks in severity 2 weeks after

the nodes of Ranvier and the axon. The presence of anti- onset.

bodies to GM1 ganglioside is particularly common when One recent study highlighted the course of 95 chil-

GBS follows infection by C jejuni. The strongest connec- dren with GBS in a prospective study. (2) Most study par-

tion with antiganglioside antibodies is found in the MFS, ticipants had AIDP, the demyelinating form of GBS. The

in which antibodies to G1QB ganglioside are found in disease progressed to a peak in a median of 7 days. At the

>90% of patients who have this disorder. The nerves that peak, 40% were still able to ambulate, one-half of them

Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012 165

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

neurologic disorders guillain-barre syndrome

without assistance and one-half with assistance. Upper Tick paralysis is an acute peripheral neuropathy caused

extremity function was abnormal in 76%, and 9% had by a species of the Dermacentor tick in the United States

no movement at all. Forty-three percent had cranial nerve and the tick Ixodes holocyclus in Australia. Patients can

weakness, and 13% required mechanical ventilation. An present with acute ataxia or ascending paralysis or both.

additional 18% were considered to have respiratory com- Onset is usually more rapid than seen with GBS. Treat-

promise. Fifty-one percent had a least one type of auto- ment involves removal of the offending tick, and recovery

nomic dysfunction, and 79% reported pain (Table 1). is usually complete. A careful examination is important,

Patients who had AMAN and AMSAN usually present especially in children with long or thick hair, in whom

in a similar fashion to the more common AIDP, with the nding a tick can be challenging.

addition of sensory symptoms in AMSAN. MFS presents Infant botulism is a disorder of neuromuscular trans-

with external ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areexia with- mission caused by colonization of the bowel by botuli-

out signicant weakness. The rst symptom in this disor- num spores found in food or soil. It is predominately a

der usually is diplopia, which progresses to clear paralysis disorder of infants <1 year of age, an age group in which

of extraocular movements. The ataxia in MFS is not a pure GBS is rare. Much less frequently, botulism can be caused

cerebellar ataxia, although cerebellar circuits are almost by botulinum toxin in food or wounds, usually in older

certainly involved. Peripheral sensory nerves rather than individuals. Mild cases also have been seen in children re-

motor nerves are affected predominately in this syn- ceiving botulinum toxin for spasticity. Botulism differs

drome, leading to a sensory ataxia. In this case, it is from GBS in that it is usually a descending rather than

the loss of proprioception that leads to a widely based, ascending paralysis, beginning with the cranial nerves.

unsteady gait. Pupillary abnormalities and bulbar symptoms, such as

chewing and swallowing difculties, are common. If this

disorder is suspected, treatment is available in the form of

Differential Diagnosis botulism immune globulin. Untreated patients can deve-

The differential diagnosis of GBS is extensive (Table 2). lop severe respiratory compromise; so treatment must be

The most important disorders to exclude are tick paraly- started before laboratory conrmation.

sis, botulism, transverse myelitis, and a compressive spinal An acute disorder of the spinal cord can be confused

cord lesion, because these treatable diseases have presen- with GBS, especially because reexes may be absent in an

tations that mimic GBS. acute spinal cord lesion. Transverse myelitis, secondary to

Signs and Symptoms of Guillain-Barre Syndrome in a Prospective

Table 1.

Study of 95 Patients

At Presentation At Diagnosis At Peak of Illness

Symmetrical weakness 100%

Hyporeflexia or absent reflexes 100%

Gait abnormality Unsteadiness of Inability to walk Inability to walk

gait: 45% unaided: 60% unaided: 80%

Inability to walk

unaided: 24%

Pain 34% >30% 79%

Dysesthesias 4%

Cranial nerve dysfunction Diplopia: 3% 27% 46%

Facial weakness: 2%

Autonomic nervous system 33% 51%

dysfunction

Upper extremity weakness 74%

Respiratory compromise 20% 13% intubated D

18% other respiratory

compromise

Table constructed with data from: Korinthinberg R, Schessl J, Kirschner J. Clinical presentation and course of childhood Guillain-Barr syndrome:

a prospective multicentre study. Neuropediatrics. 2007;38:1017. Published with permission from Georg Thieme Verlag KG.

166 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

neurologic disorders guillain-barre syndrome

Differential Diagnosis of

Table 2. Factors That Cast Doubt

Table 3.

Guillain-Barre Syndrome on Diagnosis of Guillain-Barre

Central nervous system Syndrome

Hysterical paralysis

Marked persistent asymmetry of motor function

Cerebellum Persistent bowel or bladder dysfunction

Acute cerebellar ataxia Discrete sensory level

Spinal cord Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis > 50 cells/mm3

Transverse myelitis Ptosis

Spinal cord compression Pupillary abnormalities

Prominent bulbar signs

Anterior horn cell Descending weakness

Poliomyelitis

Reprinted with permission from Asbury AK, Cornblath DR.

Peripheral nerves Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain-Barr syndrome.

Tick paralysis (United States) Ann Neurol. 1990; 27(suppl):S22.

Toxic neuropathy

Diphtheria

Porphyria

unusual ndings in GBS. Lyme polyradiculitis can also

Neuromuscular junction

Botulism be confused with GBS, but is rarely seen as a feature of

Myasthenia gravis Lyme disease in the United States. Diphtheria and other

Tick paralysis (Australia) toxic, infectious, and metabolic neuropathies are in the

Neuromuscular blocking agents differential diagnosis, but are much less common.

Muscle

Viral myositis

Inflammatory myopathies Laboratory Tests

Metabolic myopathies The diagnosis of GBS is made on clinical grounds. Lab-

oratory tests can be conrmatory early in the course, but

treatment never should be delayed awaiting results, espe-

an infectious or autoimmune disorder, and spinal cord cially because early in the course test results may be

compression are the most common causes of acute spinal normal.

cord dysfunction. It is very important to distinguish these Cerebrospinal uid (CSF) evaluation and electromy-

disorders from GBS because early corticosteroid treat- ography are the two laboratory tests most useful in con-

ment may improve outcome in transverse myelitis, and rming the diagnosis of GBS. MRI of the spine with

a compressive myelopathy often is a surgical emergency. gadolinium can be useful as an adjunctive test if the

Several features distinguish a spinal cord lesion from diagnosis is in question or if electromyography is not

GBS, although these characteristics may be difcult to ap- available.

preciate in a young child. These ndings include persistent The typical CSF nding in GBS is elevated protein

localized back pain, asymmetric weakness, a discrete sen- level without an elevated cell count (albuminocytologic

sory level, and bladder dysfunction. Any suspicion of a spi- dissociation). Protein concentration usually is normal in

nal cord disorder should lead to emergency imaging of the the rst few days of the illness and begins to rise by

spine (Table 3). the end of the rst week, peaking in 4 to 6 weeks. In most

A central nervous system disorder such as acute cere- cases, the CSF has <10 cells per mm3, all lymphocytes.

bellar ataxia caused by cerebellitis is in the differential di- Greater than 50 leukocytes per mm3 in the CSF should

agnosis, but strength and reexes often are preserved. lead to consideration of other diagnoses, although this

Myasthenia gravis, a disorder of neuromuscular transmis- nding does not absolutely rule out GBS.

sion, is another cause of acute weakness, but the ndings Early in the course of the disease, electromyography

of ptosis and uctuating weakness distinguish this disease ndings may be normal or minimal, such as absent F re-

from GBS. sponses. Later in the course of AIDP, there are ndings

Poliomyelitis, an infectious disorder of the anterior of prolonged distal latencies, conduction velocity slow-

horn cell, can mimic GBS. However poliomyelitis is usu- ing, and evidence of conduction block, which are all signs

ally accompanied by fever and meningismus, which are of demyelination. In the axonal forms (AMAN, AMSAN,

Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012 167

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

neurologic disorders guillain-barre syndrome

and MFS), there is reduced amplitude of compound action

potentials without conduction slowing or prolongation of Indications for ICU

Table 5.

distal latencies, which is the characteristic nding in axo-

nal injury. Monitoring

The typical MRI nding in GBS is gadolinium en- Flaccid quadriparesis

hancement of the spinal nerve roots. Rapidly progressing weakness

Asbury originally wrote a summary of criteria for GBS Vital capacity < or [ 20 mL/kg

in 1978, which was modied by Asbury and Cornblath in Bulbar palsy

1990 (Table 4). (3) Autonomic cardiovascular dysfunction

Reproduced from Agrawal S, Peake D, Whitehouse WP. Management

of children with Guillain-Barr syndrome. Arch Dis Child Pract Ed.

Management 2007;92:164 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Treatment of GBS, including the use of intravenous im-

munoglobulin (IVIG) as described below, should begin

as soon as the diagnosis is determined clinically.

The most important aspect of treatment in the child The American Academy of Neurology published a prac-

with GBS is supportive care. All children with GBS re- tice parameter in 2003 outlining treatment recommendations

quire hospital admission until their course has stabilized. for GBS. (4) The recommendations were based on strong

Those who have accid quadriparesis, a rapidly progressive data in adults and were extrapolated to children because

course, vital capacity at or below 50% of expected (<20 no well-designed randomized studies have been done in

mL/kg), bulbar palsy, or autonomic instability should children.

be monitored in an intensive care unit setting (Table 5). The practice parameter stated that there was good ev-

Close attention must be paid to pain management, idence in adults that both plasma exchange, started within

nutrition, and psychosocial needs. Rehabilitation should 4 weeks of symptoms, and IVIG started within 2 weeks of

begin as soon as diagnosis is made to prevent contractures symptoms hastened recovery in patients who were unable

and skin breakdown and to restore function. to walk independently. There was no additional benet

from the use of plasma exchange and IVIG together.

Because of the technical difculty of the use of plasma

exchange in children, IVIG has become the treatment of

Diagnostic Features of

Table 4.

choice. The recommendation has been to treat those chil-

Guillain-Barre Syndrome dren who are nonambulatory with 2 g/kg total of IVIG

in equally divided daily doses over 2 to 5 days. Common

Features required for diagnosis adverse effects of IVIG include fever, myalgia, headache,

Progressive motor weakness of more than one limb

Areflexia or marked hyporeflexia chills, nausea, and vomiting. Hypersensitivity and ana-

phylactoid reactions can occur. A full list of adverse effects

Features strongly supportive of the diagnosis

is included in the 2009 Red Book. (5)

Progression over days to < 4 weeks

Relative symmetry For children who remain ambulatory or for those chil-

Pain, often significant, at onset dren whose course has stabilized, only supportive treat-

Mild sensory symptoms or signs ment is recommended. Of course, every case must be

Cranial nerve involvement considered individually, and many child neurologists

Autonomic dysfunction

would recommend treatment in any patient who has

Absence of fever at onset of symptoms

Onset of recovery 24 weeks after onset of plateau been diagnosed as having GBS, especially if there is bul-

phase bar weakness or respiratory compromise, even in the

Laboratory features plateau phase.

Elevated cerebrospinal fluid protein level after one Korinthenberg et al, in 2005, by using some of the pa-

week of symptoms tients included in the previously mentioned study, at-

<10 leukocytes in cerebrospinal fluid tempted to answer two questions about the benets of

Slowed conduction or conduction block on IVIG use in children: (1) Can early treatment with IVIG

electromyography

before the loss of unaided walking reduce the subsequent

Modied with permission from Asbury, AK, Cornblath, DR. severity of the disease? (2) After the loss of unaided

Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain-Barr syndrome.

Ann Neurol. 1990;7(suppl 1):S22. walking, does treatment with 1 g/kg per day body

weight IVIG over 2 days result in faster recovery of

168 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

neurologic disorders guillain-barre syndrome

unaided walking than treatment with 0.4 mg/kg per day other studies of childhood GBS. Most importantly, how-

body weight over 5 days? (6) ever, no child tested had any functional disability.

The authors could not answer the rst question be-

cause the early treatment group consisted of only 21 chil-

dren, 14 of whom were randomized to the treatment

group. Of the seven in the non-treatment group, 4 be- Summary

came unable to walk and were randomized into the late

Based on strong research evidence, in countries where

treatment group, leaving only 3 children untreated.

poliomyelitis has been eliminated, GBS is the most

In the late treatment group, the time to regain inde- common cause of acquired paralysis in children. (9)

pendent walking did not differ between the 2-day and 5- Based on strong research evidence, GBS describes

day regimens. However, patients in the 2-day regimen a spectrum of disorders caused by an autoimmune

had a higher rate of early transient relapses that was sta- reaction against peripheral nerve components,

including the myelin sheath and the axon. (10)(11)

tistically signicant (P .049); but the extent of the de-

Based on strong research evidence, GBS usually is

terioration and the time to recovery were not described. preceded by a bacterial or viral infection, less likely by

Both regimens continue to be used. vaccination in the 1 to 4 weeks before onset. The

A recent retrospective study looked at immunoglobu- strongest relationship is with infection by C jejuni.

lin G (IgG) levels in adults with GBS after treatment with (12)(13)

Based on strong research evidence, GBS in children

IVIG and found a correlation with IgG levels and recov-

most often presents with symmetrical ascending

ery time, suggesting that some patients may need higher paralysis, diminished or absent reflexes, and often

or additional doses. (7) Although this nding needs to be severe pain. Pain may lead to a delay in diagnosis. (2)

replicated in a prospective study, the implications should (3)(9)(14)

be kept in mind if treating a patient who does not seem to Based on strong research evidence, the progressive

phase peaks in 7 to 14 days and can lead to various

be responding to treatment.

levels of weakness, from abnormal gait to total

Corticosteroids have been tested extensively in adult paralysis, cranial nerve weakness, pain, respiratory

GBS and are not indicated. compromise, and autonomic instability. (2)

Based on some research evidence and consensus,

children require hospitalization and often intensive

care until their condition stabilizes because of

Course and Prognosis significant risk of respiratory compromise and

The prognosis for childhood GBS generally is excellent. autonomic instability. (15)

This outcome is quite different from adults, in whom Based on strong research evidence in adults and some

morbidity and mortality are considerably higher, and se- research evidence in children, IVIG and plasma

verity of disease is correlated with outcome. exchange hasten recovery from GBS in patients with

impaired ability to ambulate. (4)(6)

Although treatment with IVIG is believed to hasten

Based primarily on consensus, IVIG is the treatment of

recovery, and thus reduce complications associated with choice in children with GBS. (6)(9)(15)

prolonged disability, IVIG therapy is not felt to inuence Based on strong research evidence, the prognosis for

ultimate outcome. Older studies in children report full re- full functional recovery in childhood GBS is excellent.

covery within 6 to 12 months, with the majority of those (2)(8)(9)

who do not recover fully having only mild disabilities.

In the study cited above, improvement was noted rst at

a median of 11 days, ability to walk unaided returned in a References

median of 43 days, and 75% became symptom free in a me- 1. American Academy of Pediatrics. Meningococcal infections. In:

dian of 106 days. (2) Sensory disturbances, early fatigability, Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book:

and dyscoordination remained a problem for some. 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk

Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:463

Another study looked at 47 children 2 years after re- 2. Korinthenberg R, Schessl J, Kirschner J. Clinical presentation

covery from GBS. (8) On detailed examination, 46% had and course of childhood Guillain-Barr syndrome: a prospective

some residual neurologic ndings, including 27% with multicentre study. Neuropediatrics. 2007;38(1):1017

decreased or absent deep tendon reexes and 15% with 3. Asbury AK, Cornblath DR. Assessment of current diagnostic

sensory disturbances. Twenty-three percent had mild criteria for Guillain-Barr syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(suppl):

S21S24

weakness in at least one muscle group. In this study, youn- 4. Hughes RAV, Wijdicks EFM, Barohn R, et al; Quality Standards

ger age and rapid progression correlated with long-term Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice

weakness, but this has not been a consistent nding in parameter: immunotherapy for Guillain-Barr syndrome: report of

Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012 169

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

neurologic disorders guillain-barre syndrome

the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of infections, immune factors, and outcome in Guillain-Barr syn-

Neurology. Neurology. 2003;61(6):736740 drome. Neurology. 2001;56(6):758765

5. American Academy of Pediatrics. Passive immunization. In: 13. Rees JH, Soudain SE, Gregson NA, Hughes RA. Campylo-

Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: bacter jejuni infection and Guillain-Barr syndrome. N Engl J Med.

2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk 1995;333(21):13741379

Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:5861 14. Nguyen DK, Agenarioti-Blanger S, Vanasse M. Pain and the

6. Korinthenberg R, Schessl J, Kirschner J, Mnting JS. Intravenously Guillain-Barr syndrome in children under 6 years old. J Pediatr.

administered immunoglobulin in the treatment of childhood Guillain- 1999;134(6):773776

Barr syndrome: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):814 15. Agrawal S, Peake D, Whitehouse WP. Management of children

7. Kuitwaard K, de Gelder J, Tio-Gillen AP, et al. Pharmacokinetics with Guillain-Barr syndrome. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed.

of intravenous immunoglobulin and outcome in Guillain-Barr 2007;92(6):161168

syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(5):597603

8. Vajsar J, Fehlings D, Stephens D. Long-term outcome in children

with Guillain-Barr syndrome. J Pediatr. 2003;142(3):305309 Suggested Reading

9. Jones HR Jr. Guillain-Barr syndrome: perspectives with infants Li Z, Turner RP. Pediatric tick paralysis: discussion of two cases and

and children. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2000;7(2):91102 literature review. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31(4):304307

10. Sladky JT. Guillain-Barr syndrome: blind men describe an Legido A, Tenembaum SN, Kastsetos CD, Menkes JH. Guillain-

elephant? Neurology. 2007;69(17):16471649 Barr syndrome. In: Menkes JH, Sarnat HB, Maria BL, eds.

11. Schessl J, Koga M, Funakoshi K, et al. Prospective study on Child Neurology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams

anti-ganglioside antibodies in childhood Guillain-Barr syndrome. and Wilkins; 2006

Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(1):4852 Roodbol J, de Wit MCY, Walgaard C, de Hoog M, Catsman-

12. Hadden RD, Karch H, Hartung HP, et al; Plasma Exchange/ Berrevoets CE, Jacobs BC. Recognizing Guillain-Barr syn-

Sandoglobulin Guillain-Barr Syndrome Trial Group. Preceding drome in preschool children. Neurology. 2011;76(9):807810

PIR Quiz

This quiz is available online at http://www.pedsinreview.aappublications.org. NOTE: Since January, learners can take

Pediatrics in Review quizzes and claim credit online only. No paper answer form will be printed in the journal.

New Minimum Performance Level Requirements

Per the 2010 revision of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physicians Recognition Award (PRA) and credit system,

a minimum performance level must be established on enduring material and journal-based CME activities that are certified for AMA

PRA Category 1 CreditTM. In order to successfully complete 2012 Pediatrics in Review articles for AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM,

learners must demonstrate a minimum performance level of 60% or higher on this assessment, which measures achievement of the

educational purpose and/or objectives of this activity.

Starting with 2012 Pediatrics in Review, AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM be claimed only if 60% or more of the questions are

answered correctly. If you score less than 60% on the assessment, you will be given additional opportunities to answer questions

until an overall 60% or greater score is achieved.

1. A 7-year-old presents to your clinic after three days of worsening, unsteady gait. Among the following, the

finding most typical of Guillain-Barre syndrome is:

A. Absent deep tendon reflexes.

B. Papilledema.

C. Proximal weakness.

D. Ptosis.

E. Sluggish pupils.

2. You are rounding on your 12-year-old patient, hospitalized in the ICU for Guillain-Barre syndrome. Among the

following, the complication MOST likely to result from her Guillain-Barre syndrome is:

A. Autonomic instability.

B. Deep venous thrombosis.

C. Diarrhea.

D. Nephrolithiasis.

E. Sepsis.

170 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

neurologic disorders guillain-barre syndrome

3. Which of the following characterizes infant botulism rather than Guillain-Barre syndrome?

A. Age >1 year.

B. Areflexia.

C. Ascending paralysis.

D. Pupillary abnormalities.

E. Respiratory failure.

4. A 10-year-old boy is diagnosed as having Guillain-Barre syndrome after a week of wobbly gait that has now

plateaued. He has remained ambulatory throughout his illness, with minimal if any assistance required. At no

point has there been any evidence of bulbar weakness or respiratory compromise. Of the following therapies, an

appropriate treatment having the lowest potential for adverse effects would be:

A. Ceftriaxone.

B. Intravenous immunoglobulin.

C. Mechanical ventilation.

D. Plasma exchange.

E. Supportive care.

5. An 8-year-old girl presents to the emergency department for a history of falling and progressive gait ataxia for

at least a week. Among the following, the finding most specific in the cerebrospinal fluid for a diagnosis of

Guillain-Barre syndrome is:

A. Glucose 15 mg/dL.

B. Protein 72 mg/dL.

C. 5 red blood cells/mL.

D. 53 leukocytes/mL.

E. 62 lymphocytes/mL.

Condolences

The staff of Pediatrics in Review would like to express our sorrow at the February 17, 2012,

death of Dr. Donald Lewis, a highly respected colleague and valuable member of this editorial

board. An article co-authored by Dr. Lewis will appear in the May issue.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.4 April 2012 171

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

Guillain-Barr Syndrome

Beth A. Rosen

Pediatrics in Review 2012;33;164

DOI: 10.1542/pir.33-4-164

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/33/4/164

References This article cites 15 articles, 7 of which you can access for free at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/33/4/164#BIBL

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Neurology

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/neurology_sub

Neurologic Disorders

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/neurologic_dis

orders_sub

Allergy/Immunology

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/allergy:immun

ology_sub

Immunologic Disorders

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/immunologic_

disorders_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Instituto Nacional de Pediatria on October 9, 2014

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Osteosarcoma TreatmentDocument10 paginiOsteosarcoma TreatmentJose LuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- C4K 0133 0MC Diag EvaluationDocument9 paginiC4K 0133 0MC Diag EvaluationJose LuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- C4K 0133 0MC Diag EvaluationDocument9 paginiC4K 0133 0MC Diag EvaluationJose LuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- LemvatanibDocument10 paginiLemvatanibJose LuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Comparative Study Between Limb-Salvage and Amputation For TX Osteosarcm 2016Document7 paginiA Comparative Study Between Limb-Salvage and Amputation For TX Osteosarcm 2016Jose LuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Environmental Design BasisDocument31 paginiEnvironmental Design BasisNBTC Tubes & PipesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2008 Company Performance 2008 Company Performance & 2009 Business Outlook & 2009 Business OutlookDocument30 pagini2008 Company Performance 2008 Company Performance & 2009 Business Outlook & 2009 Business OutlookKakasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barrett Firearms - REC10 - Operators Manual 8.5x5.5 ALL REVB 17278Document22 paginiBarrett Firearms - REC10 - Operators Manual 8.5x5.5 ALL REVB 17278Ricardo C TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- CP I-O Modules PDFDocument91 paginiCP I-O Modules PDFVlad ChioreanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Answer Example Source Questio N Type Topic: Glish/Doanddoeshasandhave/Bjgd /post - HTMDocument92 paginiAnswer Example Source Questio N Type Topic: Glish/Doanddoeshasandhave/Bjgd /post - HTMFarhan HakimiÎncă nu există evaluări

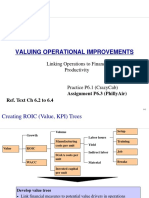

- 2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityDocument14 pagini2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityAidan HonnoldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Network 18Document44 paginiNetwork 18Ashok ThakurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction: Use Chapter 2 Section 2 in Your Flexbook To Define The FollowingDocument5 paginiIntroduction: Use Chapter 2 Section 2 in Your Flexbook To Define The FollowingNathalieÎncă nu există evaluări

- The War Archives - Machinery of Conflict. British Military Trucks of WWIIDocument84 paginiThe War Archives - Machinery of Conflict. British Military Trucks of WWIISebastijan Kerše100% (10)

- Week 2 - Risk AssessmentDocument35 paginiWeek 2 - Risk AssessmentTahir BashirÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIA Design Development Deliverable ListDocument8 paginiAIA Design Development Deliverable Listpeterhwilliams100% (1)

- CrankDocument9 paginiCrankKresna BayuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wattgate 381 Audio Grade Duplex Socket - y CableDocument20 paginiWattgate 381 Audio Grade Duplex Socket - y Cableapi-11530725100% (1)

- Galaxy NanoporeDocument11 paginiGalaxy NanoporeDeborah ShirleenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interaction of Radiation With Matter: Dhruba GuptaDocument36 paginiInteraction of Radiation With Matter: Dhruba GuptaHala SweetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enzymatic Browning and Its Prevention-American Chemical Society (1995)Document340 paginiEnzymatic Browning and Its Prevention-American Chemical Society (1995)danielguerinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Khalid DL 01 ProfileDocument2 paginiKhalid DL 01 ProfileRipunjay MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- D5293Document8 paginiD5293Carlos Olivares ZegarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application of Operations Research in Banking FinanceDocument13 paginiApplication of Operations Research in Banking FinanceInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- r48 2000e3 Rectifier User ManualDocument26 paginir48 2000e3 Rectifier User Manualjose luis rivera sotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tivax STB-T12 Owners ManualDocument32 paginiTivax STB-T12 Owners ManualJesseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To The Philosophy of Science First PartDocument138 paginiIntroduction To The Philosophy of Science First PartChandra Sekhar Sahu100% (1)

- Water Demand Fire Flow Calculation Hydraulic ModelingDocument110 paginiWater Demand Fire Flow Calculation Hydraulic ModelingArthur DeiparineÎncă nu există evaluări

- College of Nursing: Assignment ON Nursing ClinicDocument5 paginiCollege of Nursing: Assignment ON Nursing ClinicPriyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan 2aDocument5 paginiLesson Plan 2aapi-332424736Încă nu există evaluări

- 7 Must Have Equipment Items For Your Church Safety TeamDocument7 pagini7 Must Have Equipment Items For Your Church Safety TeamhmareidÎncă nu există evaluări

- RenderingDocument6 paginiRenderingJuno PajelÎncă nu există evaluări

- RDT Steering System Pressure ChartDocument118 paginiRDT Steering System Pressure ChartAnonymous 340A7vnwV1100% (2)

- Planning Installation and Configuration Guide For Windows PDFDocument228 paginiPlanning Installation and Configuration Guide For Windows PDFmmilovanmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lynn Waterhouse - Critique On Multiple IntelligenceDocument20 paginiLynn Waterhouse - Critique On Multiple IntelligencenkrontirÎncă nu există evaluări