Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Pleural Infection - Past, Present, and Future Directions

Încărcat de

Camilo VidalTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Pleural Infection - Past, Present, and Future Directions

Încărcat de

Camilo VidalDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Series

Pleural disease 1

Pleural infection: past, present, and future directions

John P Corcoran, John M Wrightson, Elizabeth Belcher, Malcolm M DeCamp, David Feller-Kopman, Najib M Rahman

Pleural space infections are increasing in incidence and continue to have high associated morbidity, mortality, and need Lancet Respir Med 2015;

for invasive treatments such as thoracic surgery. The mechanisms of progression from a non-infected, pneumonia- 3: 56377

related eusion to a conrmed pleural infection have been well described in the scientic literature, but the route by This is the rst in a Series of

two papers about pleural disease

which pathogenic organisms access the pleural space is poorly understood. Data suggests that not all pleural infections

can be related to lung parenchymal infection. Studies examining the microbiological prole of pleural infection inform See Editorial page 497

antibiotic choice and can help to delineate the source and pathogenesis of infection. The development of radiological See Comment page 505

methods and use of clinical indices to predict which patients with pleural infection will have a poor outcome, as well as See Online for a discussion with

Nick Maskell and Najib Rahman

inform patient selection for more invasive treatments, is particularly important. Randomised clinical trial and case

Oxford Centre for Respiratory

series data have shown that the combination of an intrapleural tissue plasminogen activator and deoxyribonuclease

Medicine (J P Corcoran MRCP,

therapy can potentially improve outcomes, but the use of this treatment as compared with surgical options has not been J M Wrightson DPhil,

precisely dened, particularly in terms of when and in which patients it should be used. N M Rahman DPhil) and

Department of Cardiothoracic

Surgery (E Belcher PhD), Oxford

Introduction clinical and laboratory research, and future areas of

University Hospitals NHS Trust,

Despite advances in medical diagnostic and therapeutic investigation for management of this disorder. Oxford, UK; University of

strategies, pleural infection (empyema or complex Oxford Respiratory Trials Unit,

parapneumonic eusion) is an important problem Pathophysiology Churchill Hospital, Oxford, UK

(J P Corcoran, J M Wrightson,

worldwide that continues to be associated with substantial Parapneumonic eusions occur in up to half of all

N M Rahman); NIHR Oxford

morbidity and mortality. This disorder was reliably cases of community-acquired pneumonia, with about Biomedical Research Centre,

described by Hippocrates more than two millennia ago 10% of these eusions becoming complex due to University of Oxford, Oxford,

and has claimed many lives since that time, including co-infection of the pleural space.19,20 The initial UK (J M Wrightson,

N M Rahman); Division of

those of medical luminaries such as Guillaume formation of a parapneumonic eusion is thought to be Thoracic Surgery,

Dupuytren (17771835) and William Osler (18491919). caused by increased permeability of the visceral pleural Northwestern Memorial

The basic principles of treating pleural infection, which membranes and leakage of interstitial uid in response Hospital, Northwestern

include adequate drainage of the infected uid collection, to inammation of the underlying lung parenchyma. University Feinberg School of

Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA

nutritional support, and an appropriate antibiotic therapy, The promotion of neutrophil migration together with (Prof M M DeCamp MD); and

have remained constant since the mid 20th century. the release of pro-inammatory cytokines, including Division of Pulmonary and

The incidence of pleural infection in both adult and interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumour necrosis Critical Care Medicine, Johns

paediatric populations continues to rise inexorably.15

Postulated reasons for this rise include an improvement

in clinical awareness and diagnostics, a replacement Key messages

phenomenon associated with widening use of The incidence of pleural infection continues to rise and this disease remains

multivalent pneumococcal vaccines,3,6,7 and a vulnerable associated with a poor clinical outcome, with up to 20% of patients requiring surgery

ageing population living with chronic disease. One in or dying

ve patients will need surgical intervention to adequately The process by which bacteria translocate the infected lung and multiply in the pleural

treat their pleural infection,8,9 whereas the 1-year mortality space is incompletely understood, but there is an increasing understanding of the

from the disorder has remained steady at about 20% for inammatory pathways associated with progression from simple to complex,

more than two decades.5,810 Of particular concern is that brinous infected eusion

the greatest increase in caseload is in patients aged older A score to predict clinical outcome at baseline in pleural infection has been derived and

than 65 years1 and immunocompromised patients, might be helpful in the future to plan treatment escalation and invasive interventions

whose mortality from pleural infection is above 30%,1,8,9,11 The microbiological prole of pleural infection suggests a dierent set of organisms to

related to frail health and comorbidity. There are any those seen in pneumonia, with oropharyngeal and microaspiration potential sources

number of potential reasons for the failure of treatments Conventional microbiological analysis is only slightly sensitive for the identication of

to have a substantial and lasting eect on key clinical causative organism, and this can be improved by the inoculation of pleural uid into

outcomes. These reasons might include variability in culture media bottles, and potentially in the future by the use of molecular

clinical practice and disagreement about how these microbiological techniques

patients are best managed,1217 despite the availability of Intrapleural tPA and DNase has been shown to signicantly improve drainage and can

consensus guidelines.5,18 have important eects on reducing surgical requirement and hospital stay

This Series paper addresses our understanding of Surgery remains a key treatment modality in selected cases, but the precise surgical

pleural infection, specically its pathophysiology, diag- method of choice, patient selection, and timing are not well dened

nosis, and treatment, together with developments in

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015 563

Series

Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore,

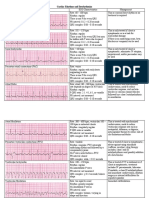

Proposed mechanism of pleural infection development in association with pneumonia

MD, USA (D Feller-Kopman MD)

Potential routes of bacterial Pneumonia-associated

Correspondence to:

entry into the pleural space inammation

Dr Najib M Rahman,

Release of pleural proinammatory cytokines

Oxford Centre for Respiratory

(eg, IL-6, IL-8, MCP, TNF, VEGF) within pleural space

Medicine, Churchill Hospital,

Oxford OX3 7LE, UK Development of sterile simple

najib.rahman@ndm.ox.ac.uk parapneumonic eusion

Inux of neutrophils and

monocytes into pleural space Increased pleural permeability

Pleural uid accumulation

1 Transpleural from adjacent consolidated lung

Pronounced role of oral anaerobes Bacterial translocation Characteristic

into pleural space Bacterial replication biochemistry

and neutrophil phagocytosis of pleural infection

2 Visceral pleural defects or stulae (low pH, low glucose,

Lung cancer, post radiotherapy, postoperative high LDH)

Fibrin deposition

(eg, broncial stump dehiscence) Suppression of septations, pleural thickening

Necrotising pneumonia, tuberculosis, fungal brinolysis (raised PAI)

Development of TGF, PDGF

pleural infection

Fibrous inelastic pleural peel

3 Haematogenous spread (bacteraemia)

5 Spread from mediastinum Uncertain whether more probable in presence of

Oesophageal rupture or other pre-existing uid (eg, hepatic hydrothorax)

4 Penetrating injury across parietal visceral pleura

Trauma

Iatrogenic (eg, post chest tube insertion)

6 Transdiaphragmatic spread

Intra-abdominal infections

Transcolonic followed by transdiaphragmatic

bacterial translocation (eg, alcoholic cirrhosis)

Figure 1: Development of pleural infectionpossible routes and mechanisms

IL-6=interleukin-6. IL-8=interleukin-8. MCP=monocyte chemoattractant protein. TNF=tumour necrosis factor-. VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor.

TGF=tumour growth factor-. PDGF=platelet-derived growth factor. LDG=lactate dehydrogenase. PAI=plasminogen activator inhibitor.

factor- (TNF), result in the development of capable of translocating through visceral mesothelial

intercellular gaps between pleural mesothelial cells21,22 cells from the parenchyma to pleural space, thereby

that facilitate the accumulation of excess pleural uid. instigating the inammatory cell and cytokine responses

During this early exudative stage, the uid is associated with pleural infection.

uncomplicated and shows no microbiological or As bacteria multiply, various changes occur within the

biochemical features of pleural infection. In most pleural space (gure 1), resulting in the characteristic

cases, the parapneumonic eusion will simply resolve clinical and biochemical features associated with a

with appropriate antibiotic therapy for the underlying complicated parapneumonic eusion, so-called because

pneumonia. of the adverse clinical outcomes seen unless the

The reasons why and means by which secondary collection is drained. Bacterial metabolism and

bacterial invasion of the pleural space occurs are neutrophil phagocytic activity result in the production

incompletely understood, a knowledge gap that is likely of lactic acid and carbon dioxide production, causing in

to be one of the barriers to therapeutic progress. turn a decrease in pleural uid pH and glucose

Although studies in animals frequently rely on articial concentration,28,29 both of which are clinically used as

infection of the pleural space via a percutaneous route laboratory markers of pleural infection.5,30 The continued

(rather than due to co-infected lung parenchyma), release of inammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6,

practical and ethical limitations exist in clinical research, interleukin-8, TNF, vascular endothelial growth factor

notably the need for repeated invasive sampling to study (VEGF), and monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP),

the evolution of pleural infection.23 An additional which are all linked to ongoing excess uid production,

complication is that pleural infection can arise occurs together with rising levels of brinolysis

spontaneously without underlying lung consolidation,2426 inhibitors such as tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor

implying contamination of the pleural space by another (PAI).31 This depression of brinolytic activity is unique

route (eg, haematogenous seeding of bacteria). to infected eusions,31 resulting in brin deposition that

Nonetheless, a study using a murine in-vivo model both coats the visceral and parietal pleural surfaces and

together with in-vitro cell line studies27 has shown that divides the space into separate pockets. Finally, purulent

Streptococcus pneumonia (S pneumonia), a common uid (empyema) develops in the context of bacterial and

cause of pleural infection in both adults and children, is leucocytic cell death and lysis.

564 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015

Series

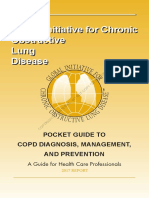

Clinical presentation consistent with pleural infection Risk stratication using baseline

(eg, fever, pleurisy, malaise, dyspnoea) physiological and biochemical parameters

Diagnostic imaging studies

Thoracic ultrasound Computed tomography

Risk stratication using thoracic Risk stratication using CT

ultrasoundeg, septations, eg, loculation, pleural

pleural thickening thickening/enhancement

Diagnostic thoracentesis with guidance

of thoracic ultrasound

Conrmed pleural infectioneg, pleural uid pH <72 or glucose <3 mmol/L;

Nucleic acid amplication frankly purulent Intermittent therapeutic

techniques for rapid thoracentesis

bacterial identication

Pleural uid for diagnostic Drainage of infected pleural

microbiology (plain and collection Thoracoscopic (surgical/

blood culture bottle culture) medical) drainage in selected

Biopsies of parietal pleura

(eg, stratied as high risk)

to increase diagnostic yield

cases

Modify antibiotics on the basis

of positive culture results and

Risk stratication on clinical response

Early combination intrapleural

basis of bacteriology Chest tube insertion with therapy in selected cases

Broad spectrum antibiotics based guidance of thoracic

on local practice and microbiology ultrasound

Intrapleural antibiotics High volume pleural irrigation

Monitor response to initial treatment during 4872 h

Treatment success: ie, clinical, radiographic Treatment failure: eg, signicant

and biochemical recovery residual collection, ongoing sepsis

Medical thoracoscopy Escalation of antibiotic therapy Referral for surgical intervention

as rescue therapy

Combination intrapleural therapy

(tPA + DNase) if surgery either

inappropriate or delayed

Choice of surgical intervention Surgical drainage and obliteration

(eg, local vs general anaesthetic; of infected pleural space

partial debridement vs full (video-assisted thoracoscopic

decortication) surgery or thoracotomy)

Figure 2: Diagnostic and therapeutic pathway for the patient with pleural infection

Black boxes, text & arrows represent established treatment pathway; red boxes, text & arrows represent potential future directions for clinical care and research.

tPA=tissue plasminogen activator.

As the infection progresses from an acute to a varies greatly between individuals, with data from

chronic state, broblast proliferation occurs along the rabbit and mouse models of pleural infection or

established brin matrix. This proliferation creates brosis suggesting a role for signalling proteins such

dense inelastic septations and collagenous thickening as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and

within and around the pleural cavity, walling o transforming growth factor- (TGF),32 which oers

residual infection but also restricting lung expansion the prospect of a novel therapeutic target for future

and compliance. The rate at which this change occurs investigation.33 Although surgical intervention is

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015 565

Series

almost certainly needed by this point to ensure Once the diagnosis of pleural infection has been

adequate clearance of infected material from the conrmed, standard treatment consists of drainage of the

pleural space, clinical outcomes are unpredictable, infected collection, usually via a percutaneous chest drain,

with some patients having no long-term sequelae and and broad-spectrum antibiotics.5 A small but substantial

others showing permanent impairment of lung proportion of patients will either not improve with this

function. conservative approach and need surgical intervention, or

will die within a year of their initial diagnosis.8,9 The

Diagnosis and outcome prediction identication of individuals who are at increased risk of

The diagnosis and treatment of pleural infection morbidity and mortality early in their treatment is of

depends on the awareness of the clinician assessing the crucial importance so that appropriate resources can be

patient (gure 2). An absence of improvement despite used to improve clinical outcome. However, clinicians

adequate antibiotic therapy for apparently uncomplicated have no reliable means by which to risk stratify patients

(assumed by the clinician) pneumonia or presentation with pleural infection. Studies on this topic have

with a pleural eusion alongside symptoms that vary implicated features including uid purulence, loculation

from those specic for infection (fever, rigours) to those of or septations within a collection, low pleural uid white

non-specic for infection (malaise, anorexia) should all cell count, pathogenic organism, and delayed presentation

prompt suspicion for a potential diagnosis of pleural and drainage, as all having a potential eect on

infection. This situation is especially true in elderly and outcome.12,37,3941 However, none of the studies were pros-

nursing-home patients who often present with an pectively validated or provided an easily accessible,

indolent course characterised by a so-called failure specic, and systematic approach to patient assessment.

to thrive, anaemia, and weight loss.34 The delayed In view of the increasingly widespread use of bedside

recognition and subsequent treatment of pleural thoracic ultrasound by respiratory clinicians, particular

infection inevitably negatively aects morbidity and interest in sonographic surrogates of poor response to

mortality,10,12 inspiring the often repeated maxim that the medical therapy in pleural infection exists.42,43 Two

sun should never set on a parapneumonic eusion. studies40,41 have directly addressed such surrogates and

In the absence of any reliable alternative means to have suggested that the presence of septations is

determine which parapneumonic eusions are either predictive of poor outcome in pleural infection. This

already infected or will probably become infected, probably supports the suggestion that the septations in

pleural uid sampling is always indicated. Current pro-brotic infected pleural collections lead to diculty

guidelines5 strongly recommend the use of thoracic in percutaneous tube drainage, and therefore ineective-

ultrasound to guide any intervention for pleural uid ness of medical therapy. However, results from these

(gure 2). With evidence showing how thoracic two studies are weak due to their unblinded design.

ultrasound reduces the risk of iatrogenic complications,35,36 Consequently, more prospective studies are needed to

blind thoracentesis in this clinical scenario is almost elucidate the clinical meaning and relevance of

impossible to justify. Ultrasound guidance is additionally septations within the infected pleural space as identied

useful in the context of suspected infection when by thoracic ultrasound. Furthermore, ultrasound is

collections might be septated, in small volume, or operator-dependent, and the expertise of the individual

multi-loculated. clinician at the bedside is probably an additional con-

The diagnosis of pleural infection can be conrmed if founding factor when applying this technique on a wide

appropriate laboratory investigations are requested and basis to guide clinical care.

correctly interpreted. If pus or microbiologically positive A prediction model,44 reported in 2014, derived from

uid (by Gram staining or culture) is clearly noted, two large prospective randomised trials8,9 of patients with

diagnosis conrmation is straightforward. However, pleural infection, oers promise in potentially allowing

almost half of infected pleural eusions turn out to the risk stratication of patients with pleural infection,

be microbiologically negative.37 The potential delay in and is being studied by a large multicentre observational

waiting for a positive culture result when infection is study (ISRCTN 50236700) to ascertain its validity. Whether

already suspected is clinically unacceptable. Therefore, this or another outcome prediction model will have any

in most cases, clinicians use pleural uid pH and inuence on either morbidity or mortality from pleural

glucose concentration as biochemical surrogates of infection is unclear. However, the availability of a validated

bacterial infection to make a diagnosis.5,30 Pleural uid risk stratication score will certainly have an eect on the

pH is most sensitive in isolation, but is also prone to way patients with a pleural infection are managed as has

instability and contamination depending on how and been the case in other respiratory diseases.

when it is analysed;38 if concerns regarding the accuracy

of a pH result exist, then pleural uid glucose can be Microbiological overview

used as a more stable and reliable measure. Ultimately, Development of pleural infection

any test should be interpreted by taking into account the The means by which bacteria enter the pleural space is

clinical presentation. being investigated.27 In view of the association between

566 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015

Series

pleural infection and pneumonia, bacterial spread across Transient bacteraemia, together with the impaired

the visceral pleura from consolidated lung probably has reticuloendothelial phagocytic activity associated with

a substantial role in pleural infection. Such a concept, cirrhosis, are proposed to cause bacterial seeding of the

however, might be a considerable oversimplication hepatic hydrothorax.Transcolonic translocation followed

since the two diseases have substantially dierent by transdiaphragmatic translocation of bacteria to the

bacteriological patterns. pleural space is another possible mechanism for pleural

Animal models of pleural infection provide useful space entry.

insight into the development of infection. Experimental More studies are needed to clarify the ability of dierent

inoculation of bacteria directly into the pleural space of bacteria to enter and cause disease within the pleural

rabbits creates biochemically and histocytologically space, particularly in view of the dierent bacteriological

similar patterns of pleural infection to human disease, features of pleural infection and pneumonia. Whereas

although substantial challenges remain in closely S pneumoniae and atypical organisms (ie, Mycoplasma

modelling human pleural infection. One challenge is that and Legionella spp) account for most community-

bacterial inoculation alone often results in either bacterial acquired pneumonia, the Streptococcus milleri (S milleri)

clearance or animal death from sepsis unless additional group, Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus), and aerobic

experimental steps are taken to allow a localised empyema Gram-negative organisms have a much larger role in

to develop. For example, nutrient broth has been injected patients with pleural infection, especially in pleural

together with the bacterial inoculant (to encourage infection acquired in hospital (see section on overall

bacterial replication within the pleural space), parenteral bacteriology). Vaccine studies in humans suggest that

antibiotics have been given (to prevent animal death from pneumococcal serotypes vary in their propensity to cause

sepsis),45 and other techniques have been used to cause pleural infection.47 Additionally, experimental evidence

pleural inammation (thereby creating an initial exudative suggests that host responses (including cytokine release

pleural eusion, proposed to sustain initial bacterial prole and mesothelial cell death) vary depending on

replication).29,46 The second challenge is that these models bacterial species, after these have gained access to the

of disease failed to reproduce the initial pneumonia often pleural space.48,49

associated with pleural infection. However, one mouse

model of pleural infection has successfully used intranasal Overall bacteriology

inoculation with S pneumoniae to cause consolidation and Large multicentre studies have characterised the

pleural infection, with a pattern similar to human bacteriological features of pleural infection and show key

disease.27 Early brinous adhesions were noted, as were dierences between community-acquired and hospital-

characteristic visceral pleural mesothelial cell changes acquired infections. Bacterial isolate data from the MIST1

(and eventual cell necrosis) and bacteria in close proximity study,8,37 the largest multicentre randomised trial of pleural

to the submesothelial cell layer. Importantly, in-vitro infection in adults with 454 participants, showed that

studies using mesothelial cells and confocal microscopy community-acquired infection in adults is most commonly

suggested that S pneumoniae crosses the mesothelial cell streptococcal (52%), with 24% from the S milleri group

layer using an intracellular route, rather than a paracellular (Streptococcus anginosus-constellatus-intermedius) and 21%

route. These ndings, taken together, are highly suggestive from S pneumonia, 20% from anaerobic microbes, 10%

of a transpleural spread of infection, at least for from S aureus, and 8% from Enterobacteriaceae (including

S pneumoniae in this mouse model of disease. Escherichia coli and Proteus spp). Hospital-acquired

With increasing use of cross-sectional imaging, pleural infection in adults is most commonly caused by S aureus

infection without adjacent consolidation has become a (35%), particularly methicillin-resistant S aureus, 18%

recognised event, although it only occurs in a few cases from Enterobacteriaceae, 18% from Streptococcus spp

(about 30% in an unreported analysis of the MIST2 (7% from the S milleri group, 5% from S pneumoniae), 12%

cohort9). This pattern of disease suggests that other from Enterococcus spp, and 8% from anaerobes. Similar

mechanisms are also responsible for bacterial entry into patterns have been observed in other studies9,50 and

the pleural space, including haematogeneous spread, highlight the importance of including methicillin-resistant

transdiaphragmatic spread, or spread from oesophageal S aureus and resistant Gram-negative coverage in empirical

or mediastinal disease (gure 1). antibiotic choice for hospital-acquired infection. Pleural

Animal models of pleural infection show that tuberculosis causes a type 4 hypersensitivity reaction

sustained pleural space bacterial replication is more within the pleural space, and is a common cause of pleural

likely in the presence of uid. Patients with pre-existing eusion in high-prevalence settings, but is beyond the

pleural eusions might therefore be at higher risk of scope of this Series paper.

pleural infection than those patients without pre- Age-dependent variation in the type of bacterial

existing pleural eusions. Indeed, spontaneous bacterial infection has also been shown, with a strikingly higher

empyema is increasingly recognised as a complication rate of S pneumoniae (up to 85%) and Streptococcus

of hepatic hydrothorax in patients with cirrhosis, pyogenes in children.51,52 Although patterns of pleural

analogous to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.24,26 infection in adults are similar in the UK,9,37 Scandinavia,53

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015 567

Series

Brims et al Meyer et al Meyer et al Lin et al Maskell et al Rahman et al Marks et al

(2014)50 (2011)53 (2011)53 (2010)55 (2006)37 (2011)9 (2012)12

Country Australia Denmark Taiwan Taiwan UK UK UK

Total number of patients or isolates 713 patients 291 isolates 139 isolates 169 isolates 396 isolates 97 isolates 406 patients

Staphylococcus aureus 12 18 6 14 16 16

Viridans streptococci 9 25 27 18

Streptococcus milleri group 7 19 21 21 4

Streptococcus pneumoniae 7 4 19 25 10

Anaerobes 17 27 18 7 6

Haemophilus inuenzae 1 4

Enterobacteriaceae 12 34 9 9 6

Klebsiella pneumoniae 3 24 24

Enterococcus spp 4 1 3 3

Pseudomonas spp 5 2 2 4

Yeasts 2 2

Mycobacterium spp 1 3 9

Values shown are expressed as % of isolates (or patients). =not reported.

Table: Representative bacteriological analysis from large international studies of pleural infection

and Australia,50 substantial geographical variation occurs vaccine) has added six further serotypes (1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F,

in Asia, where Klebsiella pneumoniae is often the most and 19A), and the consequent eects on pleural infection

common pathogen, causing up to 25% of cases (table).54,55 will be of interest for the health-care community,

Patient risk stratication might be achieved by although preliminary data have not shown an eect on

knowledge of bacterial causes, since specic mortality rates of pleural infection.62

proles are associated with each bacterial pattern. One

study showed that one-year mortality values varied Oropharyngeal commensals

depending on bacterial subtype: 17% with Streptococcal The role of oropharyngeal bacteria in pleural infection

spp, 20% with anaerobes, 45% with Gram-negative has long been recognised, particularly those bacteria

bacteria, 44% with S aureus, and 46% with mixed aerobic reported in the gingival crevices. Studies from the

bacteria.37 These ndings appear to hold true beyond the 1920s investigated the polymicrobial anaerobic and

confounding eects of whether infection was community facultatively anaerobic bacteria seen in lung abscesses

or hospital acquired; however, they do not provide and empyema. Noting these bacteria to be very similar

denitive evidence that the organisms are the cause of to gingival crevice bacteria, Smith63 inoculated the

the variation in mortality. trachea of animals with human periodontal material,

successfully causing lung abscess and empyema. This

Pneumococcal disease suggested that aspiration of these bacteria probably has

Most studies suggest that the incidence of pneumococcal a role in disease development.

infections have increased in the past 1015 years.56,57 An The S milleri group of bacteria are the most frequent

emergence of virulent serotypes, including serotypes 1, cause of community-acquired pleural infection and are

7F, and 19A, associated with pleural infection has also facultatively anaerobic commensals of the oropharynx.

taken place.58,59 One study suggested a four-fold increase They are infrequent causes of pneumonia and their

in serotype 19A,59 which is particularly associated with overrepresentation in pleural infection is therefore of

prolonged duration of fever, need for intensive care interest. Nucleic acid amplication techniques (NAAT)

admission, and surgical treatment for pleural infection.60 have reported co-localisation of S milleri and anaerobes

The original seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate in pleural infection,64 and experimental evidence

vaccine introduced in the USA in 2000 covered suggests that they are synergistic.65 Routine laboratory

serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F. Studies culturing of pleural uid samples probably under-

have suggested that widespread vaccination programmes estimates anaerobes, given their fastidious nature and

might have caused a replacement phenomenon with possible prior antibiotic use in the patient. In NAAT and

non-vaccine serotypes becoming increasingly responsible enhanced culture studies, anaerobes were noted in

for diseasein Utah, non-vaccine serotypes accounted 3374% of cases.64,66 NAAT studies have also identied

for 62% of cases of paediatric pneumococcal empyema substantial polymicrobiality associated with anaerobic

before introduction of the seven-valent pneumococcal infection, identifying many species previously not

conjugate vaccine, rising to 98% in 2007.61 The updated reported in the pleural space but almost all recognised

conjugate vaccine (13-valent pneumococcal conjugate as oropharyngeal commensals.64 Other oropharyngeal

568 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015

Series

bacteria previously isolated include Eikenella corrodens common respiratory viruses in community-acquired

(a facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative bacillus), pleural infection. One study75 used NAAT to search for

Gemella morbillorum (a microaerophilic Gram-positive nine groups of viruses in forty-eight pleural uid samples

coccus), Capnocytophaga spp (a carbon dioxide-dependent (only twelve of which were parapneumonic), but showed

Gram-negative bacillus), and Mycoplasma salivarium.64,6770 no evidence of viral infection. Another study76 reported

The frequent role and polymicrobiality of oropharyngeal evidence of a novel torque teno mini virus in pleural

bacteria in pleural infection adds to the evidence that infection, the relevance of which is unclear given the

aspiration plays a key part in the development of pleural ubiquity of such viruses in human beings and the

infection. The defective mucociliary clearance and low absence of a clear association with disease. Pleural

oxygen tension associated with an atelectatic or eusions are associated with adenovirus, hantavirus,

consolidated lung could create the ideal conditions to cytomegalovirus, and herpes viruses.

allow oropharyngeal anaerobes to ourish in the lung Although outside the scope of this Series paper, many

and potentially spread into the pleural space. protozoa can cause pleural infection including

Entamoeba histolytica, Toxoplasma gondii (particularly

Atypical pneumonia pathogens and other unusual in immunosuppressed individuals), and Trichomonas

pleural space pathogens spp. Trichomonas tenax is of particular interest, being

Despite the high frequency with which atypical organisms an oropharyngeal commensal; it is unlikely to be seen

cause pneumonia, these organisms are rarely identied as a lone pathogen since its reproduction is reliant

in pleural infection, suggesting an absence of tropism for on bacteria to provide nutrients.77 Other parasites,

the pleural space and also that routine atypical antibiotic including hydatid disease (Echinococcus spp), lariasis

coverage is not necessary for pleural infection.5,37,53 Other (Wuchereria bancrofti), Paragonimus westermani, and

bacteria reported to rarely cause pleural infection (usually Strongyloides stercoralis, have also been reported to

in immunosuppressed patients), include Pasteurella cause pleural disease.

multocida (usually associated with animal bites or

scratches), non-typhoidal salmonella, Nocardia spp, and Microbiological diagnostic yield in pleural infection

non-tuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium In view of positive culture tests in only 3040% of cases of

abscessus, chelonae, and kansasii. pleural infection,9,37 studies have addressed methods to

improve bacterial aetiological diagnosis. One study

Cirrhosis-associated spontaneous bacterial empyema showed that bedside inoculation of pleural uid into blood

Data for pathogens noted with cirrhosis-associated culture bottles (besides conventional aerobic and

spontaneous bacterial empyema are restricted to case anaerobic culture) might increase sensitivity by about

series. However, the patterns of infection are clearly not 20%.78 Diagnosis of pneumococcal disease can be

typical of either community-acquired or hospital-acquired improved by testing pleural uid using commercially-

pleural infection. Bacteria reported in these cases are available immunochromatographic pneumococcal anti-

mostly associated with the gastrointestinal tract, including gen tests. Studies have shown these tests to have sensitivity

Enterococcus spp, Salmonella enteritidis, Clostridium greater than 84% and specicity greater than 94%.79,80

perfringens, Pasteurella multocida, and Aeromonas spp.24,26 NAAT, which can amplify and detect DNA (or RNA)

present in clinical samples, has been studied in

Non-bacterial causes aetiological diagnosis. NAAT has signicant theoretical

Fungal pleural infection is associated with substantial advantages. Unlike culture tests, organism detection is

mortality and is usually iatrogenic or associated with less susceptible to prior antibiotic use. Furthermore,

comorbidities or immunosuppression.71 Candidal pleural these techniques will not suer from the methodological

infection is particularly suggestive of oesophageal diculties associated with culture of fastidious

rupture (either spontaneous or malignant) with Candida organisms. Particular success has been achieved using

albicans seen most frequently and with Candida glabrata NAAT in paediatric pleural infection to amplify

or Candida tropicalis seen less frequently. Other fungi, pneumococcal gene targets, such as the autolysin and

mostly Aspergillus spp, are also occasionally isolated pneumolysin genes.51,81,82 Besides techniques targeting

particularly in patients who have received lung single pathogens, multiplex polymerase chain reaction

transplants.71,72 Despite the ubiquity of Pneumocystis assays can test for many pathogens in a single NAAT

jirovecii in the upper and lower respiratory tract, one experiment.83 Quantication of bacterial load can likewise

study73 reported no evidence of this fungus in pleural be achieved with quantitative NAAT assays. Polymerase

infection using highly sensitive quantitative NAAT. chain reaction-based estimates of bacterial load are

Although bacterial pleural infection is associated with associated with conventional pleural uid parameters

epidemics of inuenza (eg, the 2009 H1N1 inuenza A such as pH, glucose, lactate dehydrogenase, purulence,

epidemic was associated with increased rates of and culture status. Such estimates might be associated

pneumococcal and S pyogenes pleural infection),74 only a with key clinical outcomes such as length of hospital stay

few small studies have addressed the direct role of or duration of pleural drainage.84

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015 569

Series

Technological advances and decreasing costs of nucleic might be of relevance; this mediator not only directly

acid sequencing have led to interest in the role of inhibits streptokinase but has also been shown in an

sequencing-based strategies for the diagnosis of animal model of pleural injury to contribute to the

infection. Nucleic acid sequencing, unlike other NAAT, severity of loculation and poor outcomes with intrapleural

provides a relatively assumption-free strategy for the brinolytic therapy.89,90 This principle is rearmed in a

identication of pathogens, including the recognition follow-up study by the same group in rabbits, which has

of unknown or unsuspected pathogens. A common shown that direct inhibition of PAI-1 signicantly

sequencing target used for bacterial identication is the increases the duration and ecacy (as measured by

16S ribosomal RNA gene, present in all bacteria. In the breakdown of intrapleural septations) of streptokinase.91

past, capillary-based sequencing of the 16S ribosomal Although this pathway merits further investigation as a

RNA gene was methodologically restricted in being able potential future therapeutic target, this investigation is

to identify only one pathogen per clinical sample unless presently hindered by the absence of any widely available

expensive cloning techniques were used.37,85 These means of monitoring or understanding the baseline

limitations have been overcome with next-generation PAI-1 activity in human participants with pleural

sequencing capable of identifying thousands of species infection. Since streptokinase is dependent on the

in one sample.64 physiological availability of plasminogen to form its active

complex, clinicians should consider whether it might be

Intrapleural therapies the wrong choice of brinolytic agent when used in

Besides appropriate antibiotic coverage based on local isolation. Additionally, because streptokinase has no

microbiological prevalence and resistance patterns, the eect on uid viscosity, this disadvantage together with

treatment of pleural infection necessitates adequate the development of intrapleural septations represents

drainage of the infected collection. Since most patients another barrier to successful drainage.

are initially managed with a percutaneous chest tube, To achieve successful drainage, in-vitro studies

great importance is placed on maximising the success eectively show the need to not only break down the

of this approach and limiting treatment failure. physical barrier created by brinous septations, but also

Clinicians have been interested in the potential value of to modify the viscosity of pleural uid, which is frequently

intrapleural brinolytic drugs for over half a century increased in infection as a consequence of cell

and how these drugs might prevent the progression of degradation products. Results from a study of human-

pleural infection to its more chronic brotic state.86 This derived samples of purulent uid incubated with

interest has focused on the physiological changes streptokinase, urokinase, combination streptokinase and

that occur in the infected pleural space, notably strepdornase (streptococcal deoxyribonuclease, DNase),

the depression of intrinsic brinolytic activity and or saline showed that only the uid incubated with the

consequent increase in brin load.31 Reversal of this combination streptokinase and strepdornase achieved

process has been assumed to facilitate both drainage of liquefaction.92 Similar results were seen in a larger study93

the collection by disrupting septations (further assumed of purulent pleural uid derived from an experimental

to correlate with relevant clinical outcomes) and reduce rabbit model of empyema proving the importance of

the burden of brous thickening that might otherwise DNase specically in reducing uid viscosity. The

restrict the underlying lung. combination of intrapleural direct tissue plasminogen

Streptokinase and urokinase were the rst brinolytic activator (tPA)a brinolytic agent that avoids the

drugs to be widely available and used in both adult and plasminogen complex step needed by streptokinase

paediatric pleural infection, with several case series and and DNase in another study23 that used the same animal

trials showing promise but without being able to provide model suggests additional promise in reducing the

denitive proof of eect on patient morbidity or anatomical sequelae of pleural infection.

mortality.87 An exception to this was a single, small, but For the translation of in-vitro results to a human adult

well-designed trial demonstrating reduced need for population, the MIST2 study9 was designed as a double-

surgery and reduced mortality with intrapleural strepto- placebo randomised controlled trial in pleural infection,

kinase.88 However, subsequent reporting of a large using tPA as a directly-acting brinolytic drug to disrupt

multi-centre randomised controlled trial8 of intrapleural septations and DNase with the aim of reducing uid

streptokinase versus placebo (MIST1) with 454 participants viscosity within the pleural space and enhancing drainage.

showed no evidence of a signicant improvement in key This four group study with 210 participants showed that

outcomes including death, rate of surgical referral, length combination tPA and DNase intrapleural therapy

of hospital stay, or lung function. Postulated reasons for signicantly reduced chest radiographic opacication

this include recruitment of patients who have already (the primary outcome), whereas tPA or DNase alone had

progressed to the late stages of their infection, and failure no eect compared with placebo. In the combination

to stratify for the presence or absence of septations on therapy group, secondary outcome measures including

ultrasound. Heterogeneity within the study population surgical referral rate and length of hospital stay showed

regarding the intrapleural activity of endogenous PAI-1 trends for a reduction but these were not statistically

570 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015

Series

signicant.9 Intrapleural drugs given alone showed no therapeutic lavage of the pleural space and aiding the

benet and DNase alone was actually associated with an clearance of infected materialthis would be consistent

increased surgical referral rate. No signicant increases with a pilot study that has shown a potential benet from

in mortality or adverse event rate in any experimental saline irrigation via the intercostal chest drains of people

study group were shown when compared with placebo,9 with pleural infection.96 MCP-1 is already known to have

implying a good safety prole for the combination a potential role in mechanisms of repair following

intrapleural treatment. This nding was further re- pleural injury, as well as inducing endothelial perm-

armed in a later retrospective case series.94 eability and the co-activation of other inammatory

The results of the MIST2 study9 were consistent with pathways.22,97 Scientic research is needed to better dene

those of MIST18 in ruling out a role for single agent the mechanisms of this pathway and identify potential

brinolytics in pleural infection. Therefore, the com- translational uses for clinical benet.

bination of DNase to reduce uid viscosity together with

a brinolytic such as tPA to lyse septations is probably Surgical management

most ecacious at maximising drainage. Randomisation Current guidelines5,18 advocate the use of surgery as a

of participants in the MIST2 study9 was minimised (to rescue therapy in cases of pleural infection that have

prevent imbalances between the treatments received by either failed to respond to standard medical treatment (ie,

patients in specied sub-groups) by purulence of pleural percutaneous drainage and antibiotics) or if progression

uid in view of a previous study that suggested that this to an advanced brotic state is suspected with extensive

characteristic might be associated with variation in key pleural thickening requiring decortication. The timing of

clinical outcomes from pleural infection.39 However, the surgical intervention to ensure adequate clearance of

presence of purulence was not reported to be directly infected material from the pleural space is crucial and has

associated with the ecacy of combination intrapleural been shown to be potentially life-saving in this selected

therapy in the MIST2 study. This nding implies that the population of patients. Although randomised trial data8,9

mechanism of action of DNase is not associated with a have shown that most patients (around 80%) can be

crude macroscopic measure of the likely DNA load successfully managed medically, surgery is a rst-line

within the pleural space, assuming that purulent uid treatment for pleural infection and empyema, particularly

will contain more DNA than non-purulent uid. in the USA. This approach of early surgical intervention

Therefore, small amounts of DNA within infected pleural has been justied on the basis of improved clinical

uid are possibly of some clinical relevance, either by outcome and shorter hospital stays for patients managed

causing a degree of increased uid viscosity, or perhaps in this way.12,15,98100

supporting the yet unproven hypothesis that biolm Although surgical treatment for pleural infection used

formation by bacteria within the pleural space aects to necessitate open thoracotomy, most cases are now

outcome. This theory might also explain the increased managed using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

surgical referral rate seen in those study participants who (VATS). This less invasive approach potentially widens

were randomised to intrapleural DNase alone. DNase the population who might be suitable for surgical

might have lysed biolms and released bacteria that therapy,100 although large case series2,12 from both the

could not be drained in the absence of tPA, increasing USA and UK show a continued preference to operate on

local and systemic inammation and thereby prompting younger and less comorbid individuals than seen in an

surgical referral. unselected population of patients with pleural infection.8,9

Nonetheless, the means by which brinolytics improve Nonetheless, a meta-analysis101 has suggested that VATS

clearance of infected material from the pleural space is is superior to thoracotomy with respect to length of

almost certainly more complex than mere mechanical hospital stay, postoperative morbidity and complication

disruption. Data from animal23 and human94 studies rate, and similar from the perspective of disease

show that the administration of intrapleural tPA is resolution. Surgical clearance of potentially infected

associated with up to a ten-fold increase in pleural uid material from the pleural space need not be perfect, but

output. A study using an in-vivo mouse model of pleural rather sucient to allow the patient to recover. A more

infection95 has shown this to be a class eect with conservative debridement without full decortication

streptokinase, urokinase, and tPA all stimulating excess might be adequate in selected cases to avoid

pleural uid formation. Contemporaneous studies by the compromising key long-term outcomes.102 For patients

same group using cell lines in vitro and the same murine who are not t for general anaesthesia, thoracoscopic

model suggest that this is mediated via MCP-1 expression drainage can still be used with sedation and local

and protein release by mesothelial cells, with pleural anaesthesia. This approach has been applied successfully

uid levels of this cytokine directly correlating with by thoracic surgeons103 and also physicians with expertise

volume of uid produced. Furthermore, blockade of in medical thoracoscopy but only in small studies.104,105

MCP-1 activity results in loss of the uid stimulating Compared with larger studies that have assessed the

eect of tPA in mice.95 This potent stimulation of uid ecacy of intrapleural brinolytics with or without

production might have additional benets by causing a DNase, few data are available on the use of surgery and

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015 571

Series

specically VATS as a rst-line intervention. In a small need for radical chest wall mobilisation and mutilation.116

randomised trial106 of 20 participants, which compared Open window thoracotomy remains a potentially

VATS with intercostal drainage plus intrapleural life-saving option for patients with persistent pleural space

streptokinase, VATS was successful as a rst-line therapy infection after thoracic surgical proceduresfor example,

in 91% of participants as compared with 44% in the pneumonectomy or lobectomy. Techniques centre on

streptokinase group, with patients not needing any resection of two or more ribs with marsupialisation to

additional invasive therapeutic intervention. VATS was facilitate open drainage and are associated with acceptable

also associated with a signicant reduction in the long-term outcomes in high-risk population.117 The use of

duration that a chest tube remained in situ, decreased vacuum-associated closure devices might enhance the

lengths of intensive care unit and hospital stays, and a care of these patients by accelerating recovery118 and this

reduction in overall costs.106 Other small studies107,108 of approach merits further assessment. The chronically

early surgery (ie, on or very soon after admission to infected pleural space unsuitable for additional surgical

hospital) in adults with pleural infection have also interventionfor example, in the setting of severe

suggested that this is associated with reduced hospital comorbidity or poor performance statuscan also be

lengths of stay and cost. However, these studies and managed using long-term thoracostomy. This can take the

other reported studies relating to this approach recruited form of a wide-bore drain with one-way (Heimlich) valve

small participant numbers and were underpowered as a or tunnelled catheter.119,120 In all these circumstances,

result. Nevertheless, delayed referral for surgical long-term antibiotic suppression therapy is probably

treatment does clearly result in more dicult procedures needed as an adjunct to achieve adequate sepsis control.

including a higher rate of conversion of VATS to From a practical perspective, clinicians should consider

thoracotomy.109 both the available data as well as local resources (ie, the

The surgical data in adults seem to contradict data presence of a thoracic surgeon skilled in minimally

from children with pleural infection, for whom a series invasive surgery) when devising a cogent treatment plan

of larger randomised studies110112 have shown no clinical for patients with pleural infection. A short illness of less

benet and increased cost of VATS compared with chest than 10 days without gross purulence together with the

tube drainage in brinolytic therapy. A smaller study113 absence of septations on ultrasound examination or many

that randomised 18 paediatric patients to VATS or tube locules detected by CT favours a conservative approach

thoracostomy (with or without brinolytics as indicated) using chest tube drainage with or without intra-

did nd that surgery was associated with a shorter pleural brinolytics. However, a combination of features

hospital admission. This dierence might be the result including symptom duration of more than 2 weeks, gross

of diering microbiological organisms,109 with most purulence on thoracentesis, pleural loculation, or a sign of

paediatric pleural infection being caused by S pneumoniae split pleura with pleural enhancement on CT examination

as opposed to the many dierent organisms seen in adult might suggest the presence of a visceral cortex and the

pleural infection. This dierence raises the question of need for surgical debridement to re-expand the aected

whether microbiological analysis might be one means by lung and obliterate the infected pleural space. Regardless

which patients could be stratied as low risk or high of this, although surgery remains a key intervention in

risk for morbidity or mortality. The high-risk group, the management of pleural infection, more large-scale

which potentially includes patients with Gram-negative randomised trials are needed to dene when and how it

organisms or hospital-acquired infections, is suitable for should be used in this population.

early aggressive therapy including surgery with the aim

of improving relevant clinical outcomes. However, this Future directions

paradigm of using less invasive treatment options for Although avoidance of thoracotomy is clearly a desired

patients deemed to be of low risk according to their outcome, avoidance of surgery might not be the outcome

microbiological prole might be changing with the measure that should be examined in future studies of

increasing prevalence of empyema complicating treatment in pleural infection. If VATS can be the denitive

pneumococcal pneumonia in both children and therapeutic procedure for empyema and permit discharge

adults.114,115 This alarming trend has been seen despite an from hospital in less than a week (whereas the average

increasing uptake of the multivalent pneumococcal hospital length of stay for patients receiving combination

conjugate vaccine,3,57 with the rate of pneumococcal tPA and DNase in the MIST2 trial was 12 days),9 VATS

pneumonia admissions falling at the same time as might become the procedure of choice as a rst-line

empyema increases, potentially as a result of selection of treatment advised immediately on admission to hospital.

more invasive serotypes. Additionally, since the drug cost alone of tPA and DNase

For patients in whom decortication fails, empyema intrapleural therapy is roughly 1000, early VATS might

recurs, or who have a bronchopleural stula, thoracoplasty achieve substantial cost savings in the UK and also other

might be a good surgical option in a highly selected group countries where VAT is easily available. A cost analysis of

of patients. Modern techniques using muscle aps to the MIST2 trial is underway, although a multicentre trial

eliminate residual pleural space issues have reduced the comparing early VATS with combination tPA and DNase

572 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015

Series

intrapleural therapy assessing key clinical outcomes in

pleural infection is needed, and being planned by the Search strategy and selection criteria

authors to answer these questions. We searched Embase and Medline for peer-reviewed articles

In view of the therapeutic primacy of achieving published in English from Jan 1, 2000 to Dec 31, 2014, using

successful drainage of infected material from the pleural the search terms pleural empyema, pleural eusion,

space, most studies have focused on how this might be empyema, parapneumonic eusion, pleural infection,

best achieved, for example, through chest tube drainage pleural collection, and parapneumonic infection.

(with or without intrapleural brinolytics) or by surgical Reference lists of identied articles deemed to be of relevance

intervention. A subset of patients might exist, however, were searched. Other studies including conference abstracts

in whom outpatient management using therapeutic that were known to the authors to be relevant but not

thoracentesis only whenever needed or for whom identied by this search strategy were also screened.

drainage is not even necessary, is an acceptable strategy.121

The development of a method for the identication of

these patients using a combination of clinical, radiological, Another aspect of the MIST2 protocol that is under

biochemical, and microbiological data might help reduce investigation is the dosing regimen. In the MIST2 study,9

treatment costs through avoidance of hospital admission. tPA was given and the chest drain clamped for one hour,

However, this will only be possible once our understanding followed by administration of DNase and further

of the pathogenesis and progression of pleural infection clamping of the chest drain for another hour, with this

is improved. pattern being repeated twice daily for three days. This

The primary outcome in the MIST2 study9 was labour-intensive practice has led some treatment centres

improvement in the chest radiograph (a surrogate marker to combine the drugs as part of an abridged administration

for successful clearance of the infected collection) and the protocol;94 however, we do not recommend this approach

study was underpowered to assess for signicant improve- on the basis of evidence available. More studies are

ments in mortality and morbidity from pleural infection. needed to ascertain the optimum doses of tPA and

Future large multicentre trials should address this key DNase. If a lower dosing regimen than that used in the

question and other patient-centred endpoints. Since about MIST2 study can be shown to be equally ecacious, the

70% of patients can avoid surgery, future trials should try cost-benet analysis would substantially change and

to identify patients in whom medical therapy is likely to might make combination intrapleural therapy a more

fail to enable them to be sent for surgery early during their attractive and widely available option.

admission. Likewise, the identication of patients who As with tuberculous eusions, the pleural uid might

might do well with medical therapy would be useful so not be the best type of sample to undertake culture tests.

that surgery can be avoided in these individuals (regardless Parietal pleural biopsies used in culture tests might

of the outcome of any cost-benet analysis comparing substantially increase the diagnostic microbiological yield

medical and surgical treatment pathways). in pleural infection (thereby reducing the number of

The development and validation of a risk stratication culture negative cases that have to be treated with

model for patients with pleural infection based on empirical or blind use of antibiotics), and a specic study

biochemical and physiological parameters at initial to assess this possibility is planned. Dierent antibiotics

presentation to hospital is already in progress.44 However, have the ability to penetrate the pleural space at widely

other easily accessible biomarkers could provide dierent rates, with some of them not achieving

additional prognostic information. These biomarkers therapeutic levels as shown in rabbits,123125 particularly for

might include radiological features such as septation spaces that are multiloculated with pus and brin.

density on ultrasound, pleural thickening or loculation on Continued investigation in both the laboratory setting

CT, or microbiological cause. These biomarkers have all and with human participants addressing the precise

been shown to have potential value in retrospective pharmacokinetics of intravenous antibiotics and how this

studies10,37,122 and merit prospective assessment on a wider translates across to the infected pleural space is necessary

scale. Newer biomarkers including MCP-195 and PAI-191 to inform clinicians. These data might aect antibiotic

are still being investigated in the laboratory setting and choice, dosing regimens, and duration of therapy. Data

are unlikely to reach the bedside for several years are also scarce regarding the intra-pleural administration

however, they oer promise as both therapeutic targets of antibiotics and whether this direct approach (as

and a means of monitoring response to treatment. Future opposed to waiting for antibiotics administered intra-

laboratory studies involving these and other biomarkers venously to gradually diuse into the pleural space) might

should also investigate the precise mechanisms by which accelerate sterilisation of the pleural space; further

intrapleural brinolytics act. An increased understanding investigation is necessary focusing on experimental

of these pathways might help us stratify patients into models together with translational studies at the bedside.

those who are likely to respond to intrapleural brinolytics Another potential therapeutic adjunct that has been

and those who might be better served by surgery in the reported and needs additional study is the use of pleural

event that initial medical treatment fails. irrigation, either with saline96 or povidone-iodine.126

www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015 573

Series

Fundamental for the improvement of management of Contributors

patients with pleural infection is an understanding of JPC and NMR conceived and designed the Series paper. JPC and JMW

did the scientic literature search and contributed equally to the

the progression from pneumonia to an infected pleural collection and analysis of the results. JPC wrote the sections on

space, where parenchymal infection is present. Little introduction, pathophysiology, diagnosis and outcome prediction, and

robust data exists describing how this process might intrapleural therapies. JMW wrote the section on microbiology. EB and

occur. We propose that the factors associated with the MMDC wrote the section on surgical management. DF-K and NMR

wrote the sections on future directions, conclusion, and revised the

development of pleural infection are probably related to article. All authors approved the nal version of the article.

host inammatory and immune status or variation, and

Declaration of interests

bacterial characteristics. Translational studies addressing JPC is study coordinator for PILOT (ISRCTN 50236700), an observational

bacterial translocation, uid formation, and the est- study of pleural infection funded by the Medical Research Council, UK.

ablishment of infectious niches within the pleural space DF-K has provided consultancy services to Spiration, Inc. NMR has

in parallel to host assessments are necessary. The provided consultancy services for Rocket Medical UK and was

corresponding author for the MIST2 study, which was supported by an

changing aspects of pneumococcal infection,3,6,7,57,115 as a unrestricted educational grant from Roche UK to the University of Oxford.

result of serotype selection after the introduction of NMR is also chief investigator for the PILOT study and is director of the

multivalent vaccines, might be one way to increase our University of Oxford Respiratory Trials Unit that published the MIST1 and

MIST2 studies. JMW, EB, and MMDC declare no competing interests.

understanding of how and why pleural infection

develops in dierent settings. Acknowledgments

No external funding was sought or needed for the production of this

The prevalence of pleural infection continues to

article. JMW and NMR are funded by the National Institute of Health

increase with substantial long-term mortality, rising as Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

high as 30% in the most elderly patients with pronounced

References

frailty or comorbidity. This high mortality is probably due 1 Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Nuorti JP, Grin MR. Emergence of

not only to the eect of medical comorbidity but also to a parapneumonic empyema in the USA. Thorax 2011; 66: 66368.

chronic inammatory eect and alteration in immune 2 Farjah F, Symons RG, Krishnadasan B, Wood DE, Flum DR.

Management of pleural space infections: a population-based

response similar to that seen in other respiratory analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007; 133: 34651.

infections, which include exacerbations of chronic 3 Li ST, Tancredi DJ. Empyema hospitalizations increased in US

obstructive pulmonary disease and community-acquired children despite pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics 2010;

125: 2633.

pneumonia.127131 The identication of strategies by which 4 Roxburgh CS, Youngson GG, Townend JA, Turner SW. Trends in

this legacy eect can be modied, for example, by pneumonia and empyema in Scottish children in the past 25 years.

optimising the management of comorbidities such as Arch Dis Child 2008; 93: 31618.

5 Davies HE, Davies RJ, Davies CW, and the BTS Pleural Disease

diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, and airways disease, is Guideline Group. Management of pleural infection in adults:

probably crucial in altering the long-term outlook after British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010.

pleural infection. Thorax 2010; 65 (suppl 2): ii4153.

6 Muoz-Almagro C, Jordan I, Gene A, Latorre C, Garcia-Garcia JJ,

Pallares R. Emergence of invasive pneumococcal disease caused by

Conclusion nonvaccine serotypes in the era of 7-valent conjugate vaccine.

Despite pronounced advances in medical and surgical Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46: 17482.

treatment, pleural infection remains an important and 7 Koshy E, Murray J, Bottle A, Sharland M, Saxena S. Impact of the

seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination (PCV7)

morbid clinical challenge. Our understanding of the programme on childhood hospital admissions for bacterial

pathophysiological process whereby organisms gain pneumonia and empyema in England: national time-trends study,

19972008. Thorax 2010; 65: 77074.

access to the pleural space and establish infection is

8 Maskell NA, Davies CW, Nunn AJ, et al, and the First Multicenter

incomplete. Future studies that address the progression Intrapleural Sepsis Trial (MIST1) Group. U.K. Controlled trial of

of pleural infection might shed light on how intrapleural streptokinase for pleural infection. N Engl J Med 2005;

interventions can reduce the substantial morbidity and 352: 86574.

9 Rahman NM, Maskell NA, West A, et al. Intrapleural use of tissue

mortality associated with this disease. Study on the plasminogen activator and DNase in pleural infection.

microbiological prole of pleural infection suggests a N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 51826.

broad range of causative organisms that are distinct 10 Nielsen J, Meyer CN, Rosenlund S. Outcome and clinical

characteristics in pleural empyema: a retrospective study.

from the causes of lung parenchymal infection. Clinical Scand J Infect Dis 2011; 43: 43035.

scoring systems to predict poor outcome in patients 11 Desai G, Amadi W. Three years experience of empyema thoracis in

with pleural infection are being assessed and might association with HIV infection. Trop Doct 2001; 31: 10607.

provide not only a method of risk stratication at 12 Marks DJ, Fisk MD, Koo CY, et al. Thoracic empyema: a 12-year

study from a UK tertiary cardiothoracic referral centre.

baseline, but also the potential to select patients early PLoS One 2012; 7: e30074.

that need more invasive and expensive treatments. 13 Davies HE, Rosenstengel A, Lee YC. The diminishing role of

Although promising data exist regarding the use of surgery in pleural disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2011; 17: 24754.

14 Corcoran JP, Rahman NM. Point: should brinolytics be routinely

intrapleural tPA and DNase treatment for pleural administered intrapleurally for management of a complicated

infection, the exact role of these treatments is uncertain, parapneumonic eusion? Yes. Chest 2014; 145: 1417.

especially compared with early VATS. More studies 15 Suchar AM, Zureikat AH, Glynn L, Statter MB, Lee J, Liu DC.

are necessary to dene the role of these treatments Ready for the frontline: is early thoracoscopic decortication the new

standard of care for advanced pneumonia with empyema?

more clearly. Am Surg 2006; 72: 68892.

574 www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 3 July 2015

Series

16 Scarci M, Zahid I, Bill A, Routledge T. Is video-assisted 40 Huang HC, Chang HY, Chen CW, Lee CH, Hsiue TR. Predicting

thoracoscopic surgery the best treatment for paediatric pleural factors for outcome of tube thoracostomy in complicated

empyema? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 13: 7076. parapneumonic eusion for empyema. Chest 1999; 115: 75156.

17 Lee SF, Lawrence D, Booth H, Morris-Jones S, Macrae B, Zumla A. 41 Chen CH, Chen W, Chen HJ, et al. Transthoracic ultrasonography

Thoracic empyema: current opinions in medical and surgical in predicting the outcome of small-bore catheter drainage in

management. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2010; 16: 194200. empyemas or complicated parapneumonic eusions.

18 Colice GL, Curtis A, Deslauriers J, et al. Medical and surgical Ultrasound Med Biol 2009; 35: 146874.

treatment of parapneumonic eusions : an evidence-based 42 Havelock T, Teoh R, Laws D, Gleeson F, and the BTS Pleural

guideline. Chest 2000; 118: 115871. Disease Guideline Group. Pleural procedures and thoracic

19 Strange C, Sahn SA. The denitions and epidemiology of pleural ultrasound: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline

space infection. Semin Respir Infect 1999; 14: 38. 2010. Thorax 2010; 65 (suppl 2): ii6176.

20 Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Murray MP, Scally C, Fawzi A, 43 Rahman NM, Singanayagam A, Davies HE, et al. Diagnostic

Hill AT. Risk factors for complicated parapneumonic eusion and accuracy, safety and utilisation of respiratory physician-delivered

empyema on presentation to hospital with community-acquired thoracic ultrasound. Thorax 2010; 65: 44953.

pneumonia. Thorax 2009; 64: 59297. 44 Rahman NM, Kahan BC, Miller RF, Gleeson FV, Nunn AJ,

21 Nasreen N, Mohammed KA, Hardwick J, et al. Polar production of Maskell NA. A clinical score (RAPID) to identify those at risk for

interleukin-8 by mesothelial cells promotes the transmesothelial poor outcome at presentation in patients with pleural infection.

migration of neutrophils: role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Chest 2014; 145: 84855.

J Infect Dis 2001; 183: 163845. 45 Sasse SA, Causing LA, Mulligan ME, Light RW. Serial pleural uid

22 Kroegel C, Antony VB. Immunobiology of pleural inammation: analysis in a new experimental model of empyema. Chest 1996;

potential implications for pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. 109: 104348.

Eur Respir J 1997; 10: 241118. 46 Strange C, Allen ML, Harley R, Lazarchick J, Sahn SA. Intrapleural

23 Zhu Z, Hawthorne ML, Guo Y, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator streptokinase in experimental empyema. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;

combined with human recombinant deoxyribonuclease is eective 147: 96266.

therapy for empyema in a rabbit model. Chest 2006; 129: 157783. 47 Fletcher MA, Schmitt HJ, Syrochkina M, Sylvester G.

24 Xiol X, Castellv JM, Guardiola J, et al. Spontaneous bacterial Pneumococcal empyema and complicated pneumonias: global

empyema in cirrhotic patients: a prospective study. Hepatology 1996; trends in incidence, prevalence, and serotype epidemiology.

23: 71923. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 33: 879910.

25 Jae A, Calder AD, Owens CM, Stanojevic S, Sonnappa S. Role of 48 Varano Della Vergiliana JF, Lansley SM, Porcel JM, et al.

routine computed tomography in paediatric pleural empyema. Bacterial infection elicits heat shock protein 72 release from

Thorax 2008; 63: 897902. pleural mesothelial cells. PLoS One 2013; 8: e63873.

26 Tu CY, Chen CH. Spontaneous bacterial empyema. 49 Lee Y, Varnao J, Rashwan R, Waterer G, Townsend T, Kay I.

Curr Opin Pulm Med 2012; 18: 35558. Staphylococcus aureus, but not other bacterial empyema

27 Wilkosz S, Edwards LA, Bielsa S, et al. Characterization of a new pathogens, induce the release of selected cytokines from

mouse model of empyema and the mechanisms of pleural invasion mesothelial cells. Respirology 2014; 19 (suppl 2): 128.

by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2012; 50 Brims F, Rosenstengal A, Yogendran, et al. The bacteriology of

46: 18087. pleural infection in Western Australia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

28 Light RW, MacGregor MI, Ball WC Jr, Luchsinger PC. Diagnostic 2014; 189: A5472.

signicance of pleural uid pH and PCO2. Chest 1973; 64: 59196. 51 Blaschke AJ, Heyrend C, Byington CL, et al. Molecular analysis

29 Sahn SA, Reller LB, Taryle DA, Antony VB, Good JT Jr. The improves pathogen identication and epidemiologic study of pediatric

contribution of leukocytes and bacteria to the low pH of empyema parapneumonic empyema. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30: 28994.

uid. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983; 128: 81115. 52 Eastham KM, Freeman R, Kearns AM, et al. Clinical features,

30 Hener JE, Brown LK, Barbieri C, DeLeo JM. Pleural uid chemical aetiology and outcome of empyema in children in the north east of

analysis in parapneumonic eusions. A meta-analysis. England. Thorax 2004; 59: 52225.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 151: 170008. 53 Meyer CN, Rosenlund S, Nielsen J, Friis-Mller A. Bacteriological

31 Idell S, Girard W, Koenig KB, McLarty J, Fair DS. Abnormalities of aetiology and antimicrobial treatment of pleural empyema.

pathways of brin turnover in the human pleural space. Scand J Infect Dis 2011; 43: 16569.

Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 144: 18794. 54 Chen KY, Hsueh PR, Liaw YS, Yang PC, Luh KT. A 10-year

32 Mutsaers SE, Kalomenidis I, Wilson NA, Lee YC. Growth factors in experience with bacteriology of acute thoracic empyema: emphasis

pleural brosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2006; 12: 25158. on Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Chest 2000; 117: 168589.

33 Kunz CR, Jadus MR, Kukes GD, Kramer F, Nguyen VN,

Sasse SA. Intrapleural injection of transforming growth 55 Lin YT, Chen TL, Siu LK, Hsu SF, Fung CP. Clinical and

factor-beta antibody inhibits pleural brosis in empyema. microbiological characteristics of community-acquired thoracic

Chest 2004; 126: 163644. empyema or complicated parapneumonic eusion caused by

34 El Solh AA, Alhajjhasan A, Ramadan FH, Pineda LA. A comparative Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan.Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;

study of community- and nursing home-acquired empyema 29: 100310.

thoracis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 184752. 56 Hendrickson DJ, Blumberg DA, Joad JP, Jhawar S, McDonald RJ.

35 Diacon AH, Brutsche MH, Solr M. Accuracy of pleural puncture Five-fold increase in pediatric parapneumonic empyema since

sites: a prospective comparison of clinical examination with introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

ultrasound. Chest 2003; 123: 43641. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008; 27: 103032.

36 Mercaldi CJ, Lanes SF. Ultrasound guidance decreases complications 57 Burgos J, Lujan M, Falc V, et al. The spectrum of pneumococcal

and improves the cost of care among patients undergoing empyema in adults in the early 21st century. Clin Infect Dis 2011;