Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Investigating Deaf Students' Use of Multimedia in Reading

Încărcat de

nbookman1990Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Investigating Deaf Students' Use of Multimedia in Reading

Încărcat de

nbookman1990Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Nikolaraizi, M., Vekiri, I., & Easterbrooks, S. (2013).

Investigating deaf students' use of visual multimedia resources

in reading comprehension. American Annals ofthe Deaf, 157 {5), 458-473.

INVESTIGATING DEAF STUDENTS' USE OF

VISUAL MULTIMEDIA RESOURCES IN READING

COMPREHENSION

MIXED RESEARCH D E SIG N was used to examine how deaf Students used

the visual resources of a multimedia software package that was designed

to support reading comprehension. The viewing behavior of 8 deaf stu-

dents, ages 8-12 years, was recorded during their interaction with mul-

timedia software that included narrative texts enriched with Greek Sign

Language videos, pictures, and concept maps. Also, students' reading

comprehension was assessed through reading comprehension ques-

tions and retelling. Analysis ofthe students' viewing behavior data, their

answers to reading comprehension questions, their "think alouds," and

their story retells indicated that they used visual resources, but they did

not exploit them in a strategic manner to aid their reading comprehen-

sion. The study underscores the important role of mediated instruction

in "visual literacy" skills that enable students to learn how to process

visual aids in a way that supports their reading comprehension.

MAGDA NIKOLARAIZI,

IoANNA VEKIRI, AND Keywords: deaf, reading, multimedia, tion, instructional, and experiential fac-

SUSAN R . EASTERBROOKS visual resources, pictures, concept tors (Wilson & Hyde, 1997), and relate

maps to cognitive processing, language com-

prehension, and learning (Marschark

NIKOLARAIZI IS AN ASSISTANT PROFESSOR.

One of tbe major concerns and chal- et al., 2009). Furthermore, these chal-

DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL EDUCATION,

lenging tasks of educators of deaf and lenges are associated with many vari-

UNIVERSITY OFTHESSALY, VOLOS, GREECE.

hard of hearing students is to enhance ables, namely the text (e.g., word

AT THE TIME OF THE PRESENT STUDY, VEKIRI

the reading comprehension perform- identification, syntax), the reader (e.g.,

WAS AN ADJUNCT LECTURER, DEPARTMENT OF

ance of their students, which, despite prior knowledge, metacognition), and

ELEMENTARY EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF

the application of years' worth of re- the context (e.g., the purpose of read-

THESSALY SHE IS NOW AN INDEPENDENT

search, appears to remain very poor ing; Paul, 1998; Wang & Paul, 2011),

RESEARCHER SPECIALIZING IN EDUCATIONAL

(Marschark et al., 2009; Paul, 1998; and concern difficulties with lower- and

TECHNOLOGY EASTERBROOKS IS A PROFESSOR,

Schirmer, 2000; Traxler, 2000). Good higher-level reading skills, such as poor

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

reading comprehension is a key to later vocabulary understanding, problems

AND SPECIAL EDUCATION, GEORGIA STATE

ability to access academic information with syntax processing (Kelly, 2007;

UNIVERSITY, ATLANTA.

through print. The challenges facing Paul, 1998), and low-quality or inappro-

deaf and hard of hearing students are priate use of metacognitive reading

attributed to linguistic, communica- strategies (Andrews & Mason, 1991;

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

Kelly, Albertini, & Shannon, 2001; Carter, 2001; Marschark, 2005; Paul, The participants performed better

Schirmer, 2003; Strassman, 1997). 1998; Schirmer, 2000). with texts with Signed English pictures,

In order to respond to the reading Research on the role of visual re- and the poor readers derived greater

comprehension needs of deaf and hard sources in the reading comprehension benefits compared with good readers.

of hearing students, enhance their of deaf and hard of hearing students Walker, Munro, and Richards (1998)

access to the curriculum, and maxi- has pointed out these resources' ben- conducted an intervention study dur-

mize their learning capacity, teachers efits. Reynolds and Rosen (1973) com- ing which they taught inferential read-

need to design and differentiate pared the roles of three instructional ing to 30 underachieving prelingually

instruction according to these stu- formats on 146 college students' text deaf readers (ages 9-18 years) through

dents' needs. Differentiated instruc- comprehension and information re- the use of pictorial material and printed

tion requires teachers to be flexible in tention. The three formats were (a) a text. The intervention was effective in

planning, decision making, and cur- narrative textbook style that included improving students' ability to make

riculum selection while considering text with vocabulary and syntax struc- inferences and their overall reading

the diverse needs of students in a class- ture that were somewhat less complex comprehension.

room (Tobin, 2008; Tomlinson, 1999; than that in a text for college-level stu- Apart from research investigating

Van Garderen & Whittaker, 2006). Also, dents, as well as eight line drawings; the effects of static visual aids on read-

based on the principles of universal (b) individualized instruction that ing comprehension, a number of

design for learning, the diverse needs included learning objectives, text infor- studies have examined the role of edu-

of learners need to be considered at mation with sentence structure slightly cational multimedia applications,

the veiy beginning stages of planning less difficult than that used in the first which have the potential to create a

and organizing for instruction, so that instructional condition, and nine line rich and interactive visual learning

as many students as possible benefit drawings, prior to which specific in- environment. Texts can be displayed

from the learning environment with- structions and self-test questions were in various forms and enriched with

out any further modifications beyond also added; and (c) a picture format, many resources, including graphics,

those incorporated into the original which entailed less and simpler text pictures, movies, animation, and sign

design (Tobin, 2008). Differentiated information comparing with the two language videos, creating a fiexible

instruction and universal design for first instructional conditions and 26 learning environment that can offer

learning are challenging approaches, picture displays, each accompanied by students the opportunity to explore

given that deaf and hard of hearing stu- labels and a brief descriptive sentence. information at their own pace and

dents constitute a heterogeneous The researchers found that the picto- engage with learning materials in a way

school population with diverse lan- rial instructional format was the most that suits their needs. Therefore, mul-

guage needs (Easterbrooks & Baker, effective for facilitating students' com- timedia can be a valuable tool in the

2002). One of the key elements of dif- prehension and information retention. implementation of differentiated in-

ferentiated instruction and universal Robbins (1983) investigated the read- struction or universal design for learn-

design for learning with regard to deaf ing comprehension performance of 49 ing (Boone & Higgins, 2007; Hitchcock,

and hard of hearing students is the cre- elementary and 32 secondary students Meyer, Rose, & Jackson, 2002; Rose,

ation of a visual learning environment. using texts with and without accompa- Hasselbring, Stahl, & Zabala, 2005).

The significance of this element relates nying sign language pictures placed Eurthermore, those multimedia tools

to the fact that all deaf and hard of above English words. Results indicated that move children through a program

hearing students, including ones with that students' reading comprehension on the basis of each individual child's

hearing aids or cochlear implants, who performance was better with the signed performance can scaffold students'

may communicate in sign or in a spo- versions of the texts. The role of Signed learning, since these tools allow stu-

ken language, have full access to English pictures in reading comprehen- dents to make progress depending

visual information and therefore can sion was also examined by Wson and on their mastery level (Cannon et al.,

benefit from the use of visual tech- Hyde (1997), in a study with 16 stu- 2011). This finding is in line with

niques, visual strategies, and visual dents 8-13 years old, who were divided Vygotsky's theory (1978, 1962/1986)

educational materials (Cannon, East- into two reading proficiency groups, that learning occurs within one's zone

erbrooks, Gagn, & Beal-Alvarez, 2001; read a signed and a nonsigned English of proximal development; therefore,

Dowaliby & Lang, 1999; Easterbrooks text, then answered reading compre- the level of difficulty of a learning task

& Baker, 2002; Luckner, Bowen, & hension questions and retold the story. should be within one's mastery level.

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNAI.S OF THE DEAF

USE OF VISUAL MULTIMEDIA IN READING COMPREHENSION

not below or above tbat level (Byrnes, student took advantage ofthe available language, and print plus pictures plus

1996; Tomlinson et al, 2003). resources, mostly the pictures or ani- sign. Reading comprehension of the

Research on multimedia technol- mations. However, he did not use ASL students was better when the stories

ogy and reading comprehension of translations or self-monitoring ques- were presented in the print-with-pic-

deaf and hard of hearing students has tions because he did not know ASL or tures format, while the worst perform-

included applications with a variety how to benefit from the questions. ance was observed when the stories

of accompanying visual resources and Within the Cornerstones approach, were presented in a print-only format.

adjunct instructional aids. More ana- Loeterman, Paul, and Donahue (2002) Wang and Paul (2011) compared

lytically Dowaliby and Lang (1999) developed multimedia educational the effectiveness of the Cornerstones

investigated tbe effecdveness of five software to enhance students' word approach, a literature-based, technol-

instructional conditions in facilitating identification, knowledge acquisition, ogy-infused literacy project, with a

comprehension of a science text by and story comprehension. Sample "Typical" instructional approach. Five

144 students enrolled in the National units included captioning, hypertext teachers with 22 students 7-11 years

Institute for the Deaf in Rochester, NY stories in which children could click old participated in the study; that is,

Thefiveconditions were (a) text only, on words for further information, and each teacher conducted both Corner-

(b) text and content movies, (c) text videotaped stories in ASL or Sign Sup- stones and Typical lessons and each

and sign movies, (d) text and adjunct ported English. Additional materials student participated in both lessons.

questions, and (e) all of these together. were used to make lesson content There were three Typical and three

The researchers found that students visual and engage children in an active Cornerstones lessons, the order of

performed better in conditions that interaction with the story. The evalua- which was alternated over three exper-

involved the adjunct questions or all tion of the program included eight iments and counterbalanced with a 1-

the supports. Kelly (1998) explored teachers who participated in a 2-week week break between the two lessons

whether silent modon pictures facili- field test with 32 deaf and hard of hear- in each experiment. In Experiment 1,

tated reading comprehension of rela- ing children 6-12 years old. Results the Typical lesson came first, then the

tive clause and passive voice printed indicated that when teachers used Cornerstones lesson. In Experiment 2,

sentences. The meaning ofthe stories technology supports along with in- the Cornerstones lesson came first,

was conveyed almost exclusively structional techniques based on the then the Typical lesson. In Experiment

through the acdons ofthe characters. knowledge model of vocabulary devel- 3, the Typical lesson came first, then

Eleven deaf adults watched short seg- opment, students' in-depth knowl- the Cornerstones lesson. There were

ments of video action and then chose edge of words increased. significant differences in outcomes

between two sentences that best Lang and Steely (2003) summarized between the Typical and Cornerstones

described the videos' action segments. three empirical research studies show- approaches in word identification and

The results indicated that the videos' ing that multimedia science lessons story comprehension in two out ofthe

context facilitated comprehension in can enhance the learning of students three experiments, though none in

proficient readers, while less able read- attending middle and high schools. word knowledge or story comprehen-

ers were not likely to benefit. Horney The researchers presented lessons sion in the third experiment. The teach-

and Anderson-Inman (1999) examined through a series of "triads," each con- ers enjoyed the technology aspects of

tbe interactions of a 12-year-old stu- taining a short text screen, an anima- the project, and the usefulness of the

dent within an electronic reading envi- tion corresponding to the text content, instructional strategies and activities in

ronment that had been designed as and an ASL version of that text. Lang the accompanying materials.

part of the Literacy-Hi project to fa- and Steely found that the students who Yoong and Kim (2011) examined

cilitate the reading comprehension used these multimedia materials gained the effects of captions on 66 adult stu-

of deaf readers. Several supportive significantly greater knowledge com- dents' content comprehension, cogni-

resources were included in this envi- pared with students who experienced tive load, and motivation in online

ronment, such as translational (e.g., standard teacher-led instruction. learning, when captions were used in

American Sign Language), illustrative In a study by Gentry, Chinn, and conjunction with sign language. Partic-

(e.g., word illustrations), summarizing Moulton (2004/2005), 28 students 9-18 ipants were randomly assigned to

(e.g., outlines) and evaluative resources years old were presented with digital either the control group or the ex-

(e.g., comprehension questions). The texts in four different formats: print perimental group. The results of the

results of the study indicated that the only, print plus pictures, print plus sign experiment indicated a significant dif-

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

ference in content comprehension their learning needs, choose the order attend to, and that they made fewer

between the two groups, but no statis- in which they are going to study them attempts to integrate text and picture

tically significant difference in cogni- relative to the text, and use cognitive information.

tive load and motivation. strategies that are appropriate for pro- Currently, there is little research

Findings from all the studies dis- cessing each resource. Students are examining how young deaf and hard of

cussed above converge in the conclu- not likely to allocate their attention to hearing readers use visual resources

sion that visual aids and multimedia particular visual resources if they are when they have access to multimodal

materials that include visual resources not aware of these resources' value texts. Such investigations can help

can support the reading compre- (Peeck, 1993). In addition, encoding researchers and educators understand

hension of deaf and hard of hearing and integrating information from the what type of instruction and assistance

students. However, this conclusion text and visual aids is a complex task, deaf readers need in order to use mul-

should be interpreted with some cau- particularly for young and less skilled timedia reading resources effectively

tion because relevant studies varied in readers who may not know appropri- Also, relevant research can guide the

terms of the instructional conditions ate cognitive strategies (Filippatou & design of appropriate software scaf-

in which visual resources were used, Pumfrey, 1996; McTigue, 2009). folds as well as teachers' efforts to help

the range and type of the resources Research with hearing readers shows students develop skills for using visual

included in the materials, and the age that even when they decide to use resources in reading comprehension.

groups of the participants. In some adjunct resources, poor readers do not In the present article, we present

studies (Dowaliby & Lang, 1999; Kelly, use them in a manner that can help findings from a study in which we

1998; Reynolds & Rosen, 1973; Yoong them better understand what they examined young severely to pro-

& Kim 2011), visual materials were read in the text (Hannus & Hyn, foundly deaf students' use of visual

used by adults. In studies involving 1999; McTigue, 2009). Specifically, stud- resources during independent reading

school-age students, visual resources ies in which eye fixation data were col- of narrative texts provided within a

were used either in the context of lected in an investigation of the role of specific package of multimedia soft-

teacher-led instruction, where stu- adjunct visual displays in expository ware. The software. See and See, was

dents' learning with the resources was text comprehension of both adult read- developed to meet deaf students'

guided (Lang & Steely, 2003; Loeter- ers (Hegarty & Just, 1989; Schnotz, needs, as part of a project focusing on

man et al., 2002; Walker et al., 1998; Picard, & Hron, 1993) and young hear- the role of multimedia visual resources

Wang & Paul, 2011), or in the context ing readers (Hannus & Hyn, 1999) in deaf children's reading comprehen-

of an experiment in which presenta- showed that although both low- and sion. It included electronic texts en-

tion of the materials was controlled by high-ability readers spent time observ- riched with Greek Sign Language

the experimenter (Lang & Steely, 2003) ing the displays, it was the high-ability (GSL) videos, pictures, and multiple-

and/or students had access to a lim- readers who could process them effec- choice comprehension questions, as

ited number of resources at a time tively and benefited most from their well as concept maps, whose role in

(Gentry et al., 2004/2005; Robbins, use. High-ability readers used better deaf students' reading comprehension

1983; Wilson & Hyde, 1997). Little is processing strategies, such as focusing had not been addressed in previous

known about how young deaf and on pertinent picture and text informa- multimedia research (Nikolaraizi &

hard of hearing readers use visual aids tion and looking back and forth many Vekiri, 2012). (The project was imple-

in the context of independent study times between the text and the illustra- mented by the University of Thessaly

when they are not guided by a more tions. The use of such strategies indi- and cofinanced by the European Social

experienced peer or adult, particularly cated that good readers tended to Fund and the Greek Ministry of Na-

when these visual resources are pro- focus their attention on main text ideas tional Education and Religious Affairs-

vided in an interactive multimedia and picture elements and tried to inte- Operational Program for Education and

reading environment (e.g., Horney & grate picture and text information. The Initial Vocational Training.)

Anderson-Inman, 1999). viewing behavior of poor readers, who Specifically, we addressed three re-

Using multimedia reading software paid attention to both important and search questions: ' :

may be challenging for young deaf and less important illustration segments

hard of hearing readers because they and did less back-and-forth looking, 1. Did students utilize the visual

must independently select from a vari- indicated that they did not know what resources of the See and See

ety of resources the ones that address picture information they needed to software (i.e., GSL, pictures, and

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

USE OF VISUAL MULTI2VIEDL;\ IN READING COMPREHENSION

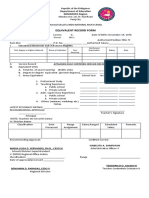

the concept map) during inde- Table 1

pendent reading and with mini- Characteristics of Study Participants (N= 8)

mal prior instruction? Which

resources of the software did

they tend to use?

2. What information did the stu-

dents extract from the visual

resources of See and See during

reading? Did they integrate the

information from these resources

during reading?

3. Did use of the visual resources

participants had severe to profound hearing loss, and had hearing parents.

of See and See aid reading com-

prehension?

Methodology used in selecting study participants, among pieces of information (Carney

Participants was estimated on the basis of perform- & Levin, 2002; Levin, Anglin, & Carney,

Eight deaf students enrolled in two pri- ance on a Greek standardized reading 1987). The concept maps illustrate the

mary special schools for the deaf par- test and teachers' reports (see Table 1). main elements of the narrative text,

ticipated in the present study Five that is, the characters, the setting, the

students were male and three were Materials: The See and See problem or the plot of the story, and

female. Their ages ranged from 7 to 12 Multimedia Softw^are the solution, which are presented

years. We selected these eight prelin- The educational software See and See according to the story's structure. In

gually deaf students on the basis of six was based on an interdisciplinary the- this way, a concept map can help learn-

criteria: oretical framework, which incorpo- ers identify the main elements of a

rated research on deaf students' story and can aid story summarizing or

1. They had severe to profound reading comprehension, the role of recalling (Castillo, Mosquera, & Pala-

hearing losses. visual resources in text comprehen- cios, 2008; Chang, Sung, & Chen, 2001;

2. They had no additional disabil- sion, and multimedia learning princi- Chmielewski & Dansereau, 1998).

ities. ples (Nikolaraizi & Vekiri, 2012). After students read the text, they

3. They could communicate in See and See includes two user inter- are forwarded to another screen to

either Greek or GSL. face components, one for students and reply to five multiple-choice reading

4. Their reading level allowed them one for teachers. The student interface comprehension questions, which en-

to participate in the test. component includes narrative texts, gage them in cognitive processing

5. They attended primary schools visual resources, and reading compre- (Andre, 1979; Dowaliby, 1992; Dowal-

for deaf students. hension questions. All reading texts iby & Lang, 1999), and therefore can

6. They were allowed to participate are from the state textbooks used in foster mathemagenic behaviors, that is

in the study. Greek primary schools, and each text "behaviors that give birth to learning"

corresponds to a specific grade and and help students achieve instruc-

Greece, a small country of about 11 reading level. Specifically, students tional goals (Rothkopf, 1970, p. 325).

million people, collects no official data have access to (a) GSL videos, both for Four text-explicit questions and one

on the exact number of deaf and hard each sentence and for the entire text; text-implicit question are included that

of hearing students attending regular (b) pictures for certain sentences or concern the most important elements

schools and schools for the deaf, as paragraphs; and (c) one concept map, in the story. All these elements, and

well as students' characteristics (e.g., which provides a visual representation therefore the answers to the ques-

home language, other disabilities, of the story structure of the narrative tions, can be identified within the con-

reading ability level). So we had to rely text. The pictures have representation cept map and the pictures that have

on a convenience sample of eight chil- and organization functions, which representation and organization func-

dren who met all of the study criteria. means that they closely correspond tions. Each reading comprehension

Reading ability level, one of the criteria to text content and present relations question and its available answers are

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

accompanied by GSL videos. When of the software by viewing reports in the concept map to the text's con-

users give an answer, they get a feed- regarding each student's interaction tent. After reading part ofthe text, the

back message about wbether their with the texts and with the software's researcher encouraged the student to

answer is right or wrong; if their resources (e.g., whether and wben read the following part and use the

answer is wrong, the message encour- they used each visual aid, whether they visual resources. He guided and

ages them to return to the text and answered a question correctly). These replied to each student's questions.

search for the right answer. options serve the aims of differend- At the end of the text, the researcher

The presentation of all visual ated instruction, because tbey allow viewed the concept map and described

resources in See and See follows mul- teachers to design activities and to scaf- or expressed his thoughts regarding it

timedia design principles. In order to fold learning according to students' in GSL.

avoid misdirecting students' atten- mastery level and diverse needs (East- After the researcher and the stu-

tion and overloading their working erbrooks & Baker, 2002; Van Garderen dent read the text, they answered the

memory with redundant information & Whittaker, 2001), and to make peri- reading comprehension questions.

(Sweller, 2005), the software does not odic assessments of students' progress The researcher read tbefirsttwo ques-

permit students to access more than (Marschark et al., 2002; Stewart & tions and all the available answers. On

one visual aid simultaneously in addi- Kluwin, 2001). the first question, he intentionally

tion to the text. To facilitate integra- selected a wrong answer. An automatic

tion of information between text and Instructional Conditions message appeared informing him that

visual aids, the spatial and the tempo- and Procedure his answer was wrong and encourag-

ral contiguity principles are applied A researcher fluent in GSL met each of ing him to go back and search for the

(Mayer, 2005b). Specifically, the visual the eight students two times. The two right answer. The researcher followed

aid window is placed right above the meetings took place over 4 days, and this instruction, re-read certain parts

text, and each visual aid is presented each lasted approximately 1 hour. In of the text, used the available visual

concurrently with the text. Also, the the first meeting, the researcher resources, and then selected the right

students can enlarge each visual aid, demonstrated tbe software and ex- answer. On the second question, the

but if they do so, they do not have plained what the student could expect, researcher pretended tbat he did not

access to the text. Further, the text sen- and in the second meeting the testing understand the question or a certain

tence or paragraph corresponding to took place. Specifically, in the first answer, and he chose to view the

each GSL video or picture, respec- meeting the researcher selected a text related GSL video. Then, the student

tively, is highlighted to signal its rela- that corresponded to the student's was asked to reply to the questions

tionship with the video or the picture reading comprehension level, which that followed. If the student could not

(Mayer, 2005b). The design ofthe pic- was assessed before the researcher understand a question, tbe researcher

tures is based on tbe coherence prin- demonstrated the software. This eval- encouraged viewing of the GSL video.

ciple (Mayer, Bove, Bryman, Mars, & uation was based on a Greek reading Also, if the student selected a wrong

Tapangco, 1996): Each picture is espe- test that was administered to each stu- answer, the automatic instruction

cially created to depict text informa- dent individually and on teachers' message appeared saying that the stu-

tion that is essential for understanding judgments. During the demonstration dent could go back to the text and

tbe main ideas of each paragraph or ofthe software, the researcher started read part of it or view the visual

section. Finally, the software follows reading a section of the text and used resources again. After answers had

the segmenting principle (Mayer, the visual resources (GSL videos and been given to all the questions, the

2005a) because it enables students to pictures) within the section. While researcher shut down the computer

control the pace of their reading and viewing the GSL videos and the pic- and asked the student to recall in GSL

choose when and how many times tures, the researcher explained that or in Greek everything he or she

tbey want to view each of the visual these corresponded to the highlighted remembered regarding the text. The

aids. sentences within the text. Also, the researcher gave the following prompts

The second user interface compo- researcher modeled "think-aloud" to the students, only when the stu-

nent concerns teachers, and enables behavior by describing in GSL what dents did not tell or sign anything:

them (a) to modify the existing read- he saw in the pictures and the con- "What happened at the beginning?"

ing texts and resources or create new cept map, and related the information "What happened then?" and "What

ones, and (b) to monitor students' use that was illustrated in the pictures and happened at the end?"

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

USE OF VISUAL MULTIMEDIA IN READING COVIPREHENSION

when the demonstration was over, picture "think-aloud" protocols, and translations of each text sentence; the

the researcher met each student once text recalls. text GSL video, which provided a trans-

more for the testing to take place. It is lation of the entire text; and the ques-

important to note that there was no Software Reports tion GSL videos, which provided

systematic instruction on use of the Software reports provided data regard- translations of each of the multiple-

software, as the aim of the present ing each student's viewing behavior, choice questions; and the concept

study was to record students' behavior that is, which resources, how many map) as well as when and how each

with minimal prior instruction. In the times, and when the student chose to student responded to the multiple-

second meeting, the researcher se- view them. Also, we checked students' choice questions. For example. Figure 1

lected a text on the basis of the stu- reading comprehension scores, that is, shows that Student A, who spent

dent's reading level and asked the how many questions they answered approximately 800 seconds with the

student to read the text, reply to five correctly in their first and subsequent software, chose to view a picture at the

multiple-choice reading comprehen- trials. Then we created a graph for 75th second during reading, then con-

sion questions, and recall the story. each student (see Figures 1-8) show- tinued reading without using any other

Before reading the text, the researcher ing when, during the reading, he or resource until about the 430th second,

reminded the student that he or she she selected each of the visual when the student chose to view the

could use all the visual resourcesthat resources, (i.e., the pictures; the sen- concept map. A few seconds later. Stu-

is, pictures, sentence GSL videos, tence GSL videos, which provided dent A selected the text GSL video and

whole GSL videos, the concept map,

and the question GSL videos. Also, the Figure 1

researcher encouraged the student to Viewing Behavior of Student A

"think aloud" his or her thoughts and Wrong Answer

descriptions when viewing the pic-

Right Answer

tures and the concept map. The sec-

ond meeting, including the student's Question GSL Video

interaction with the software, the Concept Map

"think aloud" during viewing of the

Text GSL Video

pictures, and the recalls after he or

she read the texts, was videotaped. Sentence GSL Video

Picture

Data Analysis

All videotapes were transcribed by 200 400 600 800

two researchers fluent in GSL. Tran-

Time in seconds

scripts contained student "think

alouds" and text recalls in GSL as well

as researchers' notes on students' Figure 2

other actions while they used the soft- Viewing Behavior of Student B

ware (i.e., their reading of the text VWong Answer

and answering of the questions, their

Right Answer

selection of software resources, and

any other comments they made while Question GSL Video

interacting with the software). A

Concept Map

mixed research design was imple-

mented in the present study includ- Text GSL Video

ing qualitative and quantitative data, Sentence GSL Video

that is, descriptive statistics, mostly

Picture

used to support the presentation and

understanding of the qualitative data.

Eollowing is an analytical description 200 400 600 800

of data analysis of software reports. Time in seconds

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNAI.S OF THE DEAF

Figure 3 then viewed another picture. Student

Viewing Behavior of Student C

A provided three right answers in a

Wrong Answer row, then a wrong answer, then two

Right Answer

right answers. Information obtained

from the software reports was cross-

Question GSL Video checked and interpreted with the use

Concept Map of video data that contained the stu-

dents' "think alouds" and their actions

Text GSL Video -- -

when they used the software.

Sentenoe GSL Video

Picture rv Picture "Think-Aloud" Protocols

In picture "think-aloud" protocols, we

200 400

looked for evidence regarding stu-

X) 800

dents' use of picture information. In

Time in seconds

particular, we examined whether stu-

dents focused on text-relevant picture

information and whether they inte-

Figure 4 grated picture and text information.

Viewing Behavior of Student D For each student's picture "think

Wrong Answer aloud," we recorded the number of

idea units (Mayer, 1985) that were (a)

R^ht Answer included in the text and the picture

Question GSL Video and (b) included only in the picture.

"An idea unit expresses one action or

Concept Map _

event or state, and usually corresponds

Text GSL Video to a single verb clause. Thus, each idea

Sentence GSL Video unit consists of a predicateeither a

verb or a location or a time marker

Picture

and one or more arguments" (Mayer,

1985, p-71). For example, in the sen-

200 400 600 800 tence 'All students went to the moun-

Time in seconds tain and played," there are two idea

units within the sentence, because of

the two main verbs went and played.

Examples of idea units in student pic-

Figure 5 ture "think alouds" are provided in

Viewing Behavior of Student E Table 2.

Wrong Answer

Text Recalls

Right Answer

The students' GSL recalls were scored

Question GSL Video for (a) the number of text idea units

Concept Map

that corresponded to text idea units

from the original text (Mayer, 1985)

Text GSL Video

and (b) for recall accuracy (Andrews,

Sentence GSL Video Winograd, & DeVille, 1994). We first

developed one list containing all the

Picture

idea units that were included in the

two original narrative texts (Text A and

250 soo 750 1000 Text B), as well as a second list with

Time in seconds the idea units that represented the

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

USE OF VISUAL MULTIMEDIA IN READING COZVIPREHENSION

Figure 6 main story elements (information on

Viewing Behavior of Student F the characters, the setting, main events

Wrong Answer or actions, and story ending). Text A (a

grade-level 2 passage) contained 15

Right Answer

idea units (5 of which were main story

Question GSL Video elements) and Text B (a grade-level 4

passage) contained 31 idea units (of

Ctoncept Map-

which 10 were main story elements).

Text GSL Video- Then, each student's recall protocol

was divided into idea units that were

Sentence GSL Video -

compared to the idea units from the

Roture original text. When an idea unit in the

recall protocol was similar to the idea

300 600 900 1200 1500 unit from the original text, that idea

unit was scored as "present." The recall

Time in seconds

accuracy of each idea unit was scored

as follows:

Figure 7

Viewing Behavior of Student G 1. An idea unit in the recall proto-

col received 3 points if it was a

close paraphrase of the original

idea unit and included both the

main point and the details of the

original idea unit.

2. An idea unit in the recall proto-

col received 2 points if it fell

between a close and a far para-

phrase and included only the

main point and few or no details

of the original idea unit.

400 800 1200 1600 2000 3. An idea unit in the recall proto-

Time in seconds col was given 1 point if it was a

far paraphrase, partly correct, or

incomplete.

Figure 8

Viewing Behavior of Student H

Table 3 presents the scoring system

for the analysis of student recalls. For

each student we calculated the per-

centage of recalled text idea units, the

percentage of recall accuracy, and the

percentage of main text idea units

recalled, that is, the idea units that

included main story elements. Also,

we classified the idea units in each stu-

dent's recall protocol, based on

whether the units were (a) directly

drawn from the text, (b) drawn from

300 600 900 1200 1500 the pictures but not included in the

Time in seconds text, or (c) not included in the text or

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNAI^ OE THE DEAF

Table 2 that all students used the visual re-

Examples of Idea Units in Student Picture "Think Alouds" sources that were provided in the soft-

Idea units in student picture "thini< aiouds" ware during both text reading and

Text idea units included in the text Included only in the picture question answering, and they did so in

Red poppies, yellow and white There are yellow a similar manner. Figures 1-8 present

daisies have sprouted everywhere. flowers everywhere. information on each student's viewing

All trees are in full leaf. The tree branches are behavior. As the figures show, students

in fuli leaf. tended to follow the same viewing pat-

I can see a bird's nest. tern, which was partly demonstrated

The kids are biking happily. by the researcher during the demon-

stration of the software and implicitly

prompted by the software: Students

the pictures but inferred by the stu- Results read one section of the text at a time,

dent. Next, we calculated the percent- Did students use the visual resources and when they encountered a picture

age of idea units that were identified in of the See and See software during button, they stopped reading to view

each student's recall based on the lat- reading with minimal prior instruc- the corresponding picture. When stu-

ter classification. tion? Which resources of the software dents zoomed into a picture, they had

Scoring of all "think alouds" and did they tend to use? Students did use access only to the picture and not to

recalls was done independently by the the visual resources during reading the text, because the picture window

first two authors. Interrater reliability with minimal instruction, and they was enlarged, covering the whole com-

ranged from .87 to .93, and conflicting tended to use similar resources. Our puter screen. After zooming out of the

judgments were resolved through analysis of students' viewing behavior picture, students continued reading the

discussion. based on the software reports shows next text segment. Only three instances

Table 3

Coding System for Analyzing Student Recalls: Examples of Idea Units in the Text and in Student Recalis

Examples of idea units in student recalis

Drawn from Inferred by

Drawn from the text the pictures the students

Close paraphrase Near paraphrase Far paraphrase

Text idea units (3 points) (2 points) (1 point)

J1WE.

All the kids went to The kids are at the Some kids go to the

the nearest mountain. mountain, nearby. slope of the mountain.

All trees are in full leaf. In the meadow there are There are trees.

trees with thick leaves.

Red poppies, yellow There are many flowers Some yellow flowers They looked at the

and white daisies have

sprouted everywhere.

and they are yellow and

white, there are so many!

have sprouted, so nice! various flowers.

W

The kids are

biking.

The swallow

picked up a

worm with

I I1 its beak.

Their fathers

agreed to let .

I1, them play

whatever they

1 wanted.

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNAI^ OF THE DEAF

USE OF VISUAL MULTIMEDL^ IN READING COMPREHENSION

of the use of the sentence GSL videos See and See during reading? Did they was also idendfied while students were

during reading were identified: Stu- integrate the information from these viewing the concept map, which they

dents B, C, and F each chose to view resources during reading? While view- read after reading the entire text. They

the sentence GSL videos when tbey ing the pictures, six students "thought read the concept map, but they never

encountered unknown words or aloud"; that is, they described or went back and forth between the text

phrases. The rest ofthe students, who expressed their thoughts regarding and the concept map to integrate the

also could not identify the meaning of the pictures in GSL. Two students information from the two sources.

some words or phrases, did not chose viewed the pictures but did not "think They just read the concept map and

to watch the sentence GSL videos. aloud." Table 4 shows the total number then proceeded to the reading com-

However, after reading the entire text, of idea units produced by each stu- prehension questions.

all students viewed the GSL video for dent, as well as the percentages of text- Taken together, tbesefindingsindi-

the whole text and the concept map. related and picture-related idea units. cate that students did attend to the pic-

Following text reading, students Our analysis of students' picture "think- tures. Also, students' inspections did not

moved on to the multiple-choice com- aloud" protocols shows that the pro- appear to be guided only by text ideas.

prehension quesdons. While attempt- portion of idea units that were related Rather, their attention was also dis-

ing to understand the meaning of the to the text ranged from 39.5% to tracted by picture elements irrelevant to

questions and their available answers, 80.0%, which indicates that when stu- the text's content. Finally, students did

five students (A, B, C, E, and G) chose dents inspected the pictures they did not try to coordinate information from

to view at least one of the GSL videos locate text-relevant information. How- the text and the pictures.

that corresponded to the question and ever, students also attended to infor- Did the use ofthe visual resources

its answers. Also, Student C returned mation within the pictures that was of See and See aid reading compre-

to the text and reviewed a sentence not related to the text. The proportion hension? We gathered information

GSL video. In their second attempt of idea units that corresponded to the about children's reading comprehen-

and after giving a wrong answer, all stu- pictures' content but were not related sion performance after one training

dents except Student D, who replied to the text ranged from 20.0% to session to see if the use of visual

correctly in the first attempt, re-read 60.5%. Our data on students' viewing resources aided reading comprehen-

the text and reviewed the visual behavior, based on the software re- sion. Text comprehension evaluation

resources. Specifically, two students ports and the videotape transcripts, was based on students' text recalls and

(A and B) re-read part ofthe texts, one indicate that, regardless of whether their performance on the reading

student (C) reviewed a short sentence their descriptions were text related or comprehension questions (see Table

GSL video, three students (E, F, and picture related, students did not try to 5). We found that students replied cor-

H) reviewed the concept map, and compare picture and text information rectly to three (60%) or four (80%) out

one student (G) reviewed the pictures by going back to read the correspon- of the five reading comprehension

and the concept map. Students F, G, ding part of the text and then back questions in their first attempts. Our

and H, wbo read tbe longer passage, again to the pictures to review them in analysis of students' text recall proto-

revisited the concept map several relation to the text. A similar pattern cols shows that, overall, students were

times in their second attempts to

answer questions (see Figures 6-8).

Tabie 4

In summary, during reading, the stu- Picture Think-Aloud Protocol Data, by Student

dents viewed most visual resources one

Student Idea units (N) Text-related idea units (%) Picture-related idea units (%)

after another, in a sequence tbat was

Text A

implicitly prompted by the software. In

their attempts to reply to the reading

comprehension questions, they rarely

re-read text sections or reviewed the

visual resources, but they made more

selections of specific resources when

their trials were unsuccessful.

H 66.6 33.4

Wbat information did the students

Note. Students F and G did not think aloud.

extract from the visual resources of

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANN.M.S OF THE DEAF

quite successful at comprehending the Table 5

main ideas of the text they had read, as Individual Students'Text Comprehension Soores

seven of them recalled 8096-100% of Correct Comprehension Comprehension

main story elements (see Table 5). In responses to of fuil-story of main-idea Recaii accuracy

addition, students recalled 53.3%-82.4% Student questions (%) idea units (%) units (%)

of the total amount of text idea units, Text A

and had a recall accuracy ranging from

50.0% to 83.3%. Our analysis showed

that students recalled not only text-

related information but also informa-

tion that was drawn exclusively from

the pictures or inferred by the stu-

dents themselves. The percentage of

picture-drawn idea units ranged from

5.5% to 27.3%, and the inferences con-

stituted 8.3% to 40.0% of the total

amount of idea units in students'

recalls (see Table 6). Table 6

Students demonstrated similar Student Text Recali Data

viewing behaviors and comparable Text-based Picture-based Inferred-idea

reading comprehension performance Student idea units (%) idea units (%) units (%)

in terms of the number of main-idea Text A

and full-story idea units they produced

in their GSL recalls, as well as the num-

ber of correctly answered questions.

Given the small number of study par-

ticipants and the lack of a comparison

group, it is hard to detect a striking

pattern indicating a relationship be-

tween students' use of the visual

resources and their text comprehen-

sion. However, a closer examination of

each individual student's viewing

behavior and reading performance systematic instruction took place, and, whether the selection of the resources

indicates that in some instances stu- as we discuss below, it is most likely was motivated by a general curiosity to

dents benefited from the use of the that the students would have bene- find out "what was there" or the stu-

resources. In particular, five students fited from multiple sessions of instruc- dents' need to monitor and augment

(C, E, F, G, and H) who gave wrong tion on the software to learn how to their text understanding. The beneficial

responses to some of the comprehen- use the feedback build into it to their role of the visual resources was more

sion questions appeared to benefit best advantage. evident when students replied to the

from their subsequent return to the reading comprehension questions. It is

text and the use of the visual re- Discussion possible that the limited instruction

sources, given that they were success- Regarding the two first research ques- regarding the software did not enable

ful in their following attempts. On the tions in the present study, our data indi- students to understand how to use the

other hand, in certain cases the inap- cated that students enjoyed and used visual resources strategically so that

propriate use of the resources, and most of the visual resources in the they could more effectively increase

specifically the emphasis on picture software, with which they interacted their reading comprehension.

elements that were not relevant to the independently without following spe- Specifically, during reading, stu-

text's content, affected their text recall- cific teacher guidelines. Regarding the dents chose to see the pictures, but

ing. It is worth noting, though, that no third question, it was not always clear when they inspected them, they did

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

USE OF VISUAL MULTITVEDIA IN READING COMPREHENSION

not look only for specific text informa- students viewed the concept map. used the visual resources, mostly the

tion; rather, they tended to pay atten- Although all students viewed and read concept map. This behavior maybe an

tion to everything that appeared the information within the concept indicator of the low levels of metacog-

interesting to them, even if it was not map, they never attempted to relate nitive skills that deaf students often

necessarily relevant to the text. These the concept map to the text by going appear to have (Strassman, 1997).

particular pictures were designed so back to the text, searching for and Although their preference to review

as to correspond closely to text con- identifying the information in the con- the concept map possibly indicates

tent, but they also included a few cept map within the text, and then that the students were aware that the

"background" elements (e.g., sun and returning to the concept map. map included all the required informa-

clouds in the sky) that were not part of Among all the visual resources, the tion to reply to the questions, they

the narrative text and not important GSL sentence videos were rarely used. decided to review the concept map

for understanding its meaning. Stu- The students preferred to watch the and re-read some sections in the text

dents identified information that could whole GSL video after reading the in their second attempt to reply to the

be identified within the text but also entire text instead of using the sen- questions. Wood Griffiths, and Webster

paid attention to picture elements that tence GSL videos during reading to (1981) found that deaf children did not

were irrelevant to the text. The per- repair possible misunderstandings of use a feeling-of-knowing judgment

centages of text-unrelated idea units text meaning. Their viewing behavior before answering. In a study by Davey

in the protocols of Students C and E might indicate that the students did (1987), deaf students seemed unaware

were as high as 60.5 and 52.4, respec- not monitor their reading comprehen- of the role of the look-back strategy,

tively showing that these students dis- sion and possibly were not aware of although they replied correctly to

tributed their attention nearly equally their reading comprehension difficul- more questions when they looked

among relevant and irrelevant picture ties. Another interpretation could be back to the text. Also, in the same

elements. Furthermore, students' be- that they found the whole GSL video study they used the look-back strategy

havior while viewing the visual re- more helpful. Instead of interrupting mostly to complete a task, while, in a

sources indicated that they did not their reading, they preferred to read study by LaSasso (1986, 1987), deaf

attempt to relate the information from the entire text and then watch the students used the look-back strategy

the visual resources to the text. Specifi- whole GSL video tofillin possible gaps as a visual matching technique, and

cally, while viewing the pictures, stu- in their understanding. While the not as a metacognitive strategy. The

dents did not go back to the text to whole GSL video was in operation, the participants in our study probably

read the highlighted part correspon- corresponding part of the text was became aware of their comprehension

ding to the picture, and did not review highlighted on the basis ofthe tempo- gaps after giving the wrong answer, or

the picture again in order to compare ral contiguity principle (Mayer, 2005b); became aware of the beneficial role of

it to the information in the text. It is this helped them understand which the concept map when they were

possible that students remembered part of the text related to the video. prompted by the software to go back

text information and therefore could Students' behavior was somewhat to the text and search for the right

relate picture to text information with- different when they replied to the answer. The prompts provided by the

out returning and re-reading the rele- reading comprehension questions. In software encouraging students to go

vant part of the text. Nevertheless, theirfirstattempt to reply students did back to the text and search for the

their attention to elements both rele- not return to the text and its accompa- right answer might have encouraged

vant and irrelevant to the text picture nying visual resources to search for them to use the concept map and

indicates that they treated pictures as information that could help them an- helped them to realize that its role was

extensions of the story they read and swer the questions. Students used the not to supplement or decorate the text

not as alternative representations of GSL question videos corresponding to but to help them comprehend the

the same text content. Furthermore, each question and its answers, which text.

their viewing behavior with pictures helped them understand the meaning We take this combined information

affected their text recalls, which were ofthe questions and the answers, and to mean that in addition to learning

based on the text but also partly on then replied immediately In their sec- how each of the resources in See and

content drawn exclusively from the ond trial, though, after replying incor- See functions, children need to ana-

pictures. A similar nonstrategic view- rectly, they returned to the text to lyze the new information they have

ing behavior was also identified when inspect several text sections and also gleaned with reference to their current

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

decisions about an answer, and either studies could examine the role of the As we have already mentioned,

to keep the answer they have or mod- concept map in the comprehension of such instruction did not take place in

ify it on the basis of the new informa- a text by deaf and hard of hearing stu- the present study, and the students

tion. Therefore, multiple instructional dents, either as an advance organizer probably had not acquired any related

sessions with scaffolded instruction before the text is read, as a means of experience from their teachers. There-

should be given before students are forming hypotheses about text con- fore, future intervention studies need

asked to strategically implement and tent, or, after the text is read, as a to examine whether systematic in-

exploit this software independently. In means for students to evaluate their struction in visual literacy skills and

the present study, such instructional comprehension. strategies, some of them analytically

sessions did not take place, which was GSL strategies might help deaf and presented above, can help deaf stu-

a limitation. The information gleaned hard of hearing students who know dents learn to use visual resources

in our study suggests that students GSL to use GSL videos effectively GSL effectively to enhance their text com-

should receive multiple sessions of sentence videos may help students who prehension. Also, additional research

instruction so that they may know GSL to understand unknown is needed to investigate whether one

words or difficult sentences, or to eval- of the resources of the See and See

1. determine whether visual infor- uate their hypothesis about the mean- software is more effective than another,

mation is pertinent or extrane- ing of particular words or sentences, or whether a single instruction package

ous to the print information while whole-text GSL videos might help consisting of all the components is

2. carefully implement the use of students comprehend the content of most effective. Research is also required

each visual resource (i.e., GSL, the whole text. However, it is important to determine how much instruction is

pictures, concept maps) that students be taught GSL-specific necessary for students to become effec-

3. compare and contrast informa- strategies so that they might use the tive and efficient users of the software.

tion between visual resources and GSL videos effectively. For example, Finally, research with a larger pool of

information in the text to accept strategies might involve forming hy- participants should be implemented

or reject their decisions about potheses about unknown words or the using pre- and post-study assessments

information they have gleaned meaning of text parts and then evaluat- of intervention and control groups.

ing these hypotheses using the GSL

Furthermore, sessions of instruction videos. Note

need to focus on teaching visual strate- According to Filippatou and Pum- Correspondence concerning the pres-

gies regarding each visual aid so that frey (1996), limited or inappropriate ent article should be addressed to

students become aware of the role of use of visual resources is attributable Magda Nikolaraizi, Assistant Professor

visual resources and develop specific to low levels of student awareness of in Special Education-Education of the

strategies for using them to monitor the role of visual resources and their Deaf, Department of Special Educa-

their text comprehension and repair use in reading comprehension. Visual tion, University ofThessaly, Argonafton

their misunderstandings. Future stud- resources and adjunct instructional & Philellinon, 38221, Volos, Greece.

ies could explore the effectiveness of aids may play a dynamic role in learning E-mail: mnikolar@uth.gr

teaching visual strategies, some of for deaf students (Dowaliby & Lang,

which are presented below. 1999; Lang & Steely, 2003); however,

Regarding the use of pictures, strate- all students need to know how to use References

Andre, T. (1979). Does answering higher-level

gies might involve searching for text- visual resources appropriately (Carney questions while reading facilitate productive

relevant information in the pictures, & Levin, 2002), regardless of whether learning? Review of Educational Research,

examining whether information per- they are deaf or hearing. Therefore, 49, 280-319.

Andrews, J., & Mason, J. (1991). Strategy usage

ceived in the pictures is consistent with there is a need for systematic instruc- among deaf and hearing readers. Excep-

what one has comprehended when tion in "visual literacy" skills so that stu- tional Children, 57, 536-545.

reading the text, forming hypotheses dents can learn how to process visual Andrews, J., Winograd, E, & DeVille, G. (1994).

Deaf children reading fables: Using ASL sum-

about unknown vocabulary or expres- aids and extract more and better infor- maries to improve reading comprehension.

sions based on picture content, and, mation from them, so as to increase American Annals of the Deaf, 139,378-386.

when pictures are viewed before print their reading comprehension (Hannus Boone, R., & Higgins, K. (2007). The role of

instructional design in assistive technology

information is read, making hypothe- & Hyn, 1999; Nikolaraizi & Vekiri,

research and development. Reading Research

ses about text content. Similarly, future 2012; Peeck, 1993). Quarterly,42,135-140. doi:10.1598/RRQ.42.1

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

USE OF VISUAL MULTIMEDIA IN READING COMPREHENSION

Byi'nes, J. (1996). Cognitive development and Supported text in electronic reading envi- explanatory text (pp. 65-87). Hillsdale, NJ:

/earning in instructional contexts. Need- ronments. Reading and Writing Quarterly, Erlbaum.

ham Heights, MA; Allyn & Bacon. 15, 127-168. Mayer, R. E. (2005a). Principles for managing

Cannon, J., Easterbrooks, S., Gagn, K, & Beal- Kelly L. (1998). Using silent motion pictures to essential processing in multimedia learning:

AlvarezJ. (2011). Improving DHH students' teach complex syntax to adult deaf learners. Segmenting, pretraining, and modality prin-

grammar through an individualized software Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Educa- ciples. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge

program. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf tion, 3, 217-230. handbook of multimedia learning (pp.

Education, 16, Ail-A5~l Kelly, L. (2007). The comprehension of skilled 169-182). New York, NY Cambridge Univer-

Carney, R. N., & Levin, J. R. (2002). Pictorial illus- deaf readers: The roles of word recognition sity Press.

trations still improve students' learning from and other potentially critical aspects of com- Mayer, R. E. (2005b). Principles for reducing

text. Educational Psychology Review, 14, petence. In K. Cain &J. Oakhill (Eds.), Chil- extraneous processing in multimedia learn-

5-26. dren 's comprehension problems in oral and ing: Coherence, signaling, redundancy spa-

Castillo, E., Mosquera, D., & Palacios, D. (2008). written language: A cognitive perspective tial contiguity, and temporal contiguity

Concept maps: A tool to enhance reading (pp. 244-280). New York, NY: Guilford Press. principles. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cam-

comprehension skills of children with hear- Kelly R., Albertini,J., & Shannon, N. (2001). Deaf bridge handbook of multimedia learning

ing impairments. Retrieved from http://cmc college students' comprehension and strat- (pp. 183-200). New York, NY: Cambridge

.ihmc.us/cmc2008papers/cmc2008-p247.pdf egy use. American Annals of the Deaf, 146, University Press.

Chang, K-E, Sung, Y-T, & Chen, I-D. (2002). The 385-399. Mayer, R. E., Bove, 'W, Bryman, A., Mars, R., &

effect of concept mapping to enhance text Lang, H., & Steely D. (2003). 'Web-based science Tapangco, L. (1996). 'When less is more:

comprehension and summarization./owrw/ instruction for deaf students: 'What research Meaningful learning from visual and verbal

of Experimental Education, 71, 5-23. says to the teacher Instructional Science, summaries of science textbook lessons.

Chmielewski, T. C, & Dansereau, D. F. (1998). 31, 277-298. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88,

Enhancing the recall of text: Knowledge map- LaSasso, C. (1986). A comparison of visual 64-73.

ping training promotes implicit transfer./owr- matching test-taking strategies of compara- McTigue, E. M. (2009). Does multimedia learn-

nal of Educational Psychology, 90, 407-413. bly aged normal-hearing and hearing- ing theory extend to middle-school students?

Davey, B. (1987). Postpassage questions: Task impaired subjects with comparable reading Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34,

and reader effects on comprehension and levels. Volta Review, 88, 231-241. 143-153.

metacomprehension processes. Journal of LaSasso, C. (1987). Survey of reading instruction Nikolaraizi, M., & Vekiri, I. (2012). The design of

Reading Behavior, 19, 261-283. for hearing-impaired students in the United a software to enhance the reading compre-

Dowaliby, E (1992). The effects of adjunct ques- States. Volta Review, 89, 85-98. hension of deaf children: An integration of

tions in prose for deaf and hearing students Levin, J. R., Anglln, G. J., & Carney, R. N. (1987). multiple theoretical perspectives. Educa-

at different reading levels. American Annals On empirically validating functions of pic- tion and Information Technologies, 17,

of the Deaf 137, 338-344. tures in prose. In D. M. Willows cist H. A. 167-185.

Dowaliby, E, & Lang, H. (1999). Adjunct aids in Houghton (FAs.), The psychology of illustra- Paul, P (199S). Literacy and deafness: Thedevel-

instructional prose: A multimedia study with tion: Volume 1. Basic research (pp. 51-85). opment of reading, writing, and literate

deaf college students. Journal of Deaf Stud- New York, NY: Springer thought. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn &

ies and Deaf Education, 4, 270-282. Loeterman, M., Paul, P, & Donahue, S. (2002). Bacon.

Easterbrooks, S., & Baker, S. (2002). Language Reading and deaf children. Reading Online, Peeck, J. (1993). Increasing picture effects in

learning in children who are deaf and hard 5. Retrieved from http://www.readingonline learning from illustrated text. Learning and

of hearing. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & .org/articles/loeterman/index.html Instruction, 3, 227-238.

Bacon Luckner, J., Bowen, S., & Carter, K. (2001). Visual Reynolds, H., & Rosen, R. (1973, February/

Filippatou, D., & Pumfrey, P D. (1996). Pictures, teaching strategies for students who are deaf March). The effectiveness of textbook, indi-

titles, reading accuracy, and reading compre- or hard of hearing. Teaching Exceptional vidualized, and pictorial formats for hear-

hension. Educational Research, 38,259-291. Children, 33, 38-44. ing impaired students. Paper presented at

Gentry, M., Chinn, K, & Moulton, R. (2004/ Marschark, M. (2005). Classroom interpreting the meeting of the American Educational

2005). Effectiveness of multimedia reading and visual information processing in main- Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

materials when used with children who are stream education for deaf students: Live or (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.

deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, 149, Memorex? American Educational Research ED 075 968)

394-403. Journal, 42, 727-776. Robbins, N. (1983). The effects of signed text on

Hannus, M., & Hyn, J. (1999). Utilization of Manschark, M., Lang, H., & Albertini, J. (2002). the reading comprehension of hearing

illustrations during learning of science text- Educating deaf students: Erom research to impaired children. American Annals of the

book passages among low- and high-ability practice. New York, NY Oxford University Deaf 128, 40-44.

children. Contemporary Educational Psy- Press. Rose, D., Hasselbring, T. S., Stahl, S., & Zabala,

chology, 24, 95-123. Marschark, M., Sapere, R, Convertino, C, Mayer, J. (2005). Assistive technology and universal

Hegarty M., &Just, M. A. (1993). Constructing C, 'Wauters, L., & Sarchet, T. (2009). Are deaf design for learning: Two sides of the same

mental models of machines from text and students' reading challenges really about coin. In D. Edyburn, K. Higgins, & R. Boone

digrms. Journal ofMemory and Language, reading? ^mencfl Annals of the Deaf 154, (Eds.), Handbook of special education

32, 717-742. 357-370. doi:10.1353/aad.0.0111 technology research and practice (pp.

Hitchcock, C, Meyer, A., Rose, D., & Jackson, R. Mayer, R. E. (1985). Structural analysis of science 507-518). 'Whitefish Bay, WI: Knowledge by

(2002). Providing new access to the general prose: Can we increase problem-solving per- Design.

curriculum: Universal design for learning. formance? In B. K. Britton &J. B. Black (Eds.), Rothkopf, E. Z. (1970). The concept of math-

Teaching Exceptional Children, 35, 8-17. Understanding expository text: A theoretical emagenic activities. Review of Educational

Horney, M. A., & Anderson-Inman, L. (1999). and practical handbook for analyzing Research, 40, 325-336.

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF

Schirmer, B. (2000). Language and literacy Tomlinson, C. (1999). The differentiated class- Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language.

development in children who are deaf. Need- room: Responding to the needs of alt Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Original work

ham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for published 1962)

Schirmer, B. (2003). Using verbal protocols to Supervision and Curriculum Development. Walker, L., Munro, J., & Richards, E (1998). Teach-

identify reading strategies of students who Tomlinson, C, Brighton, C, Hertberg, H., Calla- ing inferential reading strategies through pic-

are ds^t Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf han, C, Moon, T, Brimijoin, K., et al. (2003). tures. Volta Review, 100, 105-120.

Education, 8, 157-170. Differentiating instruction in response to stu- Wang, Y, & Paul, E (2011). Integrating technol-

Schnotz, W, Picard, E., & Hron, A. (1993). How dent readiness, interest, and learning profile ogy and reading instruction with children

do successful and unsuccessful learners use in academically diverse classrooms: A review who are deaf or hard of hearing: The effec-

texts and graphics? Learning and Instruc- of literature. 7oMma//or the Education of tiveness ofthe Cornerstones Project. Amer-

tion, 3, 181-199. the Gifted, 27, 119-145. ican Annals ofthe Deaf 156, 56-68.

Stewart, D., & Kluwin, T. (2001). Teaching deaf Traxler, C. (2000). The Stanford Achievement Wilson, T, & Hyde, M. (1997). The use of Signed

and hard of hearing students. Needham Test, ninth edition: National norming and English pictures to facilitate reading compre-

Heights, MA: A)lyn ec Bacon. performance standards for deaf and hard of hension by deaf students. American Annals

Strassman, B. (1997). Metacognition and reading hearing students./oMrwa/ of Deaf Studies of the Deaf 142, 333-341.

in children who are deaf: A review of the and Deaf Education, 5,337-348. doi: 10.1093/ Wood, D. J., Griffiths, A. J., & Webster, A.

reseas-ch. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf deafed/5.4.337 (1981). Reading retardation or linguistic

Education, 2,140-141. Van Garderen, D., & Whittaker, C. (2001). Plan- deficit? II: Test-answering strategies in

Sweller, J. (2005). The redundancy principle in ning differentiated, multicultural instruction hearing and hearing impaired schoolchild-

multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), for secondary inclusive classrooms. Teach- ren./Orna/ of Research in Reading, 4,

Tbe Cambridge handbooiz of multimedia ing Exceptional Children, 38,12-20. 148-156.

learning (pp. 159-166). New York, NY: Cam- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The devel- Yoong,J-O, & Kim, M. (2011). The effects of cap-

bridge University Press. opment of higher psychological processes tions on deaf students' content comprehen-

Tobin, R. (2008). Conundrums in the differenti- (M. Cole, Y John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. sion, cognitive load, and motivation in online

ated literacy classroom. Reading Improve- Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard learning. American Annals ofthe Deaf 156,

ment,45, 159-169. University Press. 283-289.

VOLUME 157, No. 5, 2013 AMERICAN ANNALS OE THE DEAF

Copyright of American Annals of the Deaf is the property of American Annals of the Deaf and its content may

not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Literacy Development in Deaf StudentsDocument12 paginiLiteracy Development in Deaf Studentsnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Issues in Second Language Literacy Education With Learners Who Are DeafDocument11 paginiIssues in Second Language Literacy Education With Learners Who Are Deafnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- I Have Ears But I Do Not HearDocument17 paginiI Have Ears But I Do Not Hearnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Is Reading Different For Deaf IndividualsDocument14 paginiIs Reading Different For Deaf Individualsnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Literacy and Linguistic Development in Bilingual Deaf ChildrenDocument14 paginiLiteracy and Linguistic Development in Bilingual Deaf Childrennbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Literacy in The Homes of Deaf ChildrenDocument26 paginiLiteracy in The Homes of Deaf Childrennbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- I Was Born Full DeafDocument21 paginiI Was Born Full Deafnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- How Deaf Bilingual Children Become Proficient ReadersDocument15 paginiHow Deaf Bilingual Children Become Proficient Readersnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- ESL Through PrintDocument14 paginiESL Through Printnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Early Visual Language Exposure and Emergent LiteracyDocument14 paginiEarly Visual Language Exposure and Emergent Literacynbookman1990100% (1)

- Examination of Evidence-Based Literacy Strategies PDFDocument15 paginiExamination of Evidence-Based Literacy Strategies PDFnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Effects of SES On Literacy Development of Deaf SignersDocument15 paginiEffects of SES On Literacy Development of Deaf Signersnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Examination of 20 Practices For DHH LearnersDocument14 paginiExamination of 20 Practices For DHH Learnersnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Developing Language and Writing Skills of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students A Simultaneous ApproachDocument25 paginiDeveloping Language and Writing Skills of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students A Simultaneous Approachnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Assessing Fitness To Stand Trial of Deaf IndividualsDocument13 paginiAssessing Fitness To Stand Trial of Deaf Individualsnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Developing Preschool Deaf Children's Language - From Educational Media SeriesDocument16 paginiDeveloping Preschool Deaf Children's Language - From Educational Media Seriesnbookman19900% (1)

- Deaf and HOH Students' Through-The-Air English SkillsDocument17 paginiDeaf and HOH Students' Through-The-Air English Skillsnbookman1990Încă nu există evaluări

- Vocab Use by Low Moderate and High Asl-Proficient Writers Compared To Hearing Esl and Monolingual SpeakersDocument18 paginiVocab Use by Low Moderate and High Asl-Proficient Writers Compared To Hearing Esl and Monolingual Speakersapi-361724066Încă nu există evaluări