Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

People v. Opida

Încărcat de

Charmila SiplonTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

People v. Opida

Încărcat de

Charmila SiplonDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

19. People v.

Opida

Re: Right to Impartial Judge

Facts:

On July 31, 1976, in QC, several persons ganged up on Galvan, stoned and hit him with beer bottles until

finally one of them stabbed him to death. The actual knife-wielder was identified as Mario del Mundo.

Nonetheless, Alberto Opida and Virgilio Marcelo were charged with murder as conspirators and, after

trial, sentenced to death.

The basis of their conviction by the trial court was the testimony of two prosecution witnesses, neither of

whom positively said that the accused were at the scene of the crime, their extrajudicial confessions,

which were secured without the assistance of counsel, and corroboration of the alleged conspiracy under

the theory of interlocking confession.

What is striking about this case is the way the trial judge conducted his interrogation of the two accused

and their lone witness, Lilian Layug.

Issue: Is the judge being impartial?

Ruling:

Yes.

Given the obvious hostility of the judge toward the defense, it was inevitable that all the protestations of

the accused in this respect would be, as they in fact were, dismissed. And once the confessions were

admitted, it was easy enough to employ them as corroborating evidence of the claimed conspiracy among

the accused.

The accused are admittedly notorious criminals who were probably even proud of their membership in the

Commando gang even as they flaunted their tattoos as a badge of notoriety. Nevertheless, they were

entitled to be presumed innocent until the contrary was proved and had a right not to be held to answer

for a criminal offense without due process of law.

The judge disregarded these guarantees and was in fact all too eager to convict the accused, who had

manifestly earned his enmity. When he said at the conclusion of the trial, "You want me to dictate the

decision now?", he was betraying a pre-judgment long before made and obviously waiting only to be

formalized.

The scales of justice must hang equal and, in fact, should even be tipped in favor of the accused because

of the constitutional presumption of innocence. Needless to stress, this right is available to every

accused, whatever his present circumstance and no matter how dark and repellent his past. Despite their

sinister connotations in our society, tattoos are at best dubious adornments only and surely not under our

laws indicia of criminality. Of bad taste perhaps, but not of crime.

In any event, convictions are based not on the mere appearance of the accused but on his actual

commission of crime, to be ascertained with the pure objectivity of the true judge who must uphold the

law for all without favor or malice and always with justice.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- United States v. Felipe Bustos Et AlDocument3 paginiUnited States v. Felipe Bustos Et AlSamuel John CahimatÎncă nu există evaluări

- People VS QuitlongDocument1 paginăPeople VS QuitlongJenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dumlao VS ComelecDocument4 paginiDumlao VS ComelecMaica MahusayÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. BugtongDocument3 paginiPeople vs. BugtongJane Yonzon-Repol0% (1)

- Iglesia Ni Cristo vs. Court of Appeals Case DigestDocument5 paginiIglesia Ni Cristo vs. Court of Appeals Case DigestBam Bathan86% (7)

- Estipona v. LobrigoDocument13 paginiEstipona v. LobrigoCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- GT-N7100-Full Schematic PDFDocument67 paginiGT-N7100-Full Schematic PDFprncha86% (7)

- Due Process DigestsDocument7 paginiDue Process DigestsNeil Owen DeonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs CayatDocument2 paginiPeople Vs CayatC Maria LuceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re Query of Mr. Roger C. PrioreschiDocument2 paginiRe Query of Mr. Roger C. PrioreschiLolit CarlosÎncă nu există evaluări

- CD - Aguirre v. Aguirre, 58 SCRA 461 (1974)Document2 paginiCD - Aguirre v. Aguirre, 58 SCRA 461 (1974)Nico NicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEOPLE VS TAMPAL CDDocument2 paginiPEOPLE VS TAMPAL CDmark paul cortejosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Padua Vs Ericta Sec 16Document2 paginiPadua Vs Ericta Sec 16JohnEval Meregildo100% (1)

- Taruc Vs Dela Cruz & Islamic Vs Exec SecDocument3 paginiTaruc Vs Dela Cruz & Islamic Vs Exec SecjelyneptÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs LumagueDocument1 paginăPeople Vs LumagueJelyn Delos Reyes TagleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baldoza Vs DimaanoDocument2 paginiBaldoza Vs DimaanoEller-JedManalacMendoza0% (1)

- 7 Casanova Vs Hors DigestDocument1 pagină7 Casanova Vs Hors DigestAljay LabugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. L-56450Document3 paginiG.R. No. L-56450Josie Jones BercesÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs MingoaDocument1 paginăPeople Vs MingoaJelyn Delos Reyes TagleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feeder International Line LTD v. CADocument2 paginiFeeder International Line LTD v. CABryan Jay NuiqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poli Case Digest (Privacy of Communications and Correspondence)Document4 paginiPoli Case Digest (Privacy of Communications and Correspondence)Chi OdanraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Right of Suspects 19-20Document3 paginiRight of Suspects 19-20Jimcris Posadas Hermosado100% (1)

- Evidence DigestDocument3 paginiEvidence DigestseventhwitchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Padua vs. ErictaDocument2 paginiPadua vs. ErictaAnna Liza FanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- US v. Ang Tang Ho 43 Phil 1Document1 paginăUS v. Ang Tang Ho 43 Phil 1Ja RuÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V Alicando GR No. 117487 (December 2, 1995)Document1 paginăPeople V Alicando GR No. 117487 (December 2, 1995)Joseph MacalintalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Echegaray V PeopleDocument3 paginiEchegaray V PeopleRaisa Hojas FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flores vs. People (G.R. No. L-25769, December 10, 1974) FERNANDO, J.: FactsDocument20 paginiFlores vs. People (G.R. No. L-25769, December 10, 1974) FERNANDO, J.: FactsRegine LangrioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandoval V Hret DigestDocument2 paginiSandoval V Hret DigestJermone Muarip100% (3)

- People of The Philippines vs. Alfredo Pascual y Ildefonso G. R. No. 172326 January 19, 2009 FactsDocument3 paginiPeople of The Philippines vs. Alfredo Pascual y Ildefonso G. R. No. 172326 January 19, 2009 FactsHemsley Battikin Gup-ayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re Cases Submitted For Decision Before Judge Damaso A. Herrera M-ViiiDocument2 paginiRe Cases Submitted For Decision Before Judge Damaso A. Herrera M-ViiiJeanella Pimentel CarasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 49 People vs. Godines 196 SCRA 765Document1 pagină49 People vs. Godines 196 SCRA 765G-one PaisonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robertson Vs BaldwinDocument5 paginiRobertson Vs BaldwinJomar TenezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Borja V Mendoza DigestDocument1 paginăBorja V Mendoza DigestJay SosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tecson VS FaustoDocument2 paginiTecson VS FaustoVal SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roan v. GonzalesDocument2 paginiRoan v. GonzalesPaolo Bañadera100% (2)

- People V Berdaje DigestDocument1 paginăPeople V Berdaje DigestJay SosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eminent Domain R V - T Issue:: Epublic S AgleDocument9 paginiEminent Domain R V - T Issue:: Epublic S AgleLorelei B RecuencoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alonte Vs SavellanoDocument2 paginiAlonte Vs SavellanoRosemary RedÎncă nu există evaluări

- CASE REPORTING Estate of Salud Jimenez V PEZADocument12 paginiCASE REPORTING Estate of Salud Jimenez V PEZAPhil Alkofero Lim Abrogar0% (1)

- Digest Magdalo-vs.-COMELEC-6-19-12Document2 paginiDigest Magdalo-vs.-COMELEC-6-19-12Rochelle GablinesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angara VS Electoral Commission DigestDocument2 paginiAngara VS Electoral Commission DigestTAU MU OFFICIALÎncă nu există evaluări

- De La Camara Vs EnageDocument1 paginăDe La Camara Vs EnageBoyet CariagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEOPLE VS TEE (Rights of The Accused)Document3 paginiPEOPLE VS TEE (Rights of The Accused)Jeanella Pimentel CarasÎncă nu există evaluări

- ETHICS Canon 3-4 DigestsDocument10 paginiETHICS Canon 3-4 DigestsDonna Mendoza100% (1)

- People vs. RamosDocument6 paginiPeople vs. RamosAndrew Lastrollo100% (1)

- Serafin Vs LindayagDocument1 paginăSerafin Vs LindayaggerlynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest - Cabatingan Vs ArcuenoDocument1 paginăCase Digest - Cabatingan Vs ArcuenoValencia and Valencia OfficeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baguio Midland CourierDocument2 paginiBaguio Midland Courieranalyn100% (1)

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondent Menandro Quiogue Jose Ma. Recto Paterno R. CanlasDocument5 paginiPetitioners vs. vs. Respondent Menandro Quiogue Jose Ma. Recto Paterno R. CanlasClintÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18.people V MalnganDocument47 pagini18.people V Malnganjuan aldabaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pretty v. UKDocument6 paginiPretty v. UKclaire beltranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Namil v. ComelecDocument2 paginiNamil v. ComelecJohn TurnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Us V Tan TengDocument6 paginiUs V Tan TengMabelAbadillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enrile v. Salazar, 186 SCRA 217Document6 paginiEnrile v. Salazar, 186 SCRA 217PRINCESS MAGPATOCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Due Process Case DigestDocument7 paginiDue Process Case DigestiheartyoulianneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Us V JavierDocument7 paginiUs V JavierOwie JoeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mercado Vs Court of First InstanceDocument2 paginiMercado Vs Court of First InstanceBananaÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs SayabocDocument2 paginiPeople Vs SayabocfriendlyneighborÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mari V CaDocument1 paginăMari V Caana ortizÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. OpidaDocument1 paginăPeople v. OpidaCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- PP Versus OpidaDocument3 paginiPP Versus OpidaJanet Tal-udanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gary Fastastico and Rolando Villanueva vs. Elpidio Malicse, Sr. and People (G.R. No. 190912, January 12, 2015)Document9 paginiGary Fastastico and Rolando Villanueva vs. Elpidio Malicse, Sr. and People (G.R. No. 190912, January 12, 2015)Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frenzel v. Catito, G.R. No. 143958, July 11, 2003Document8 paginiFrenzel v. Catito, G.R. No. 143958, July 11, 2003Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rules of Court Civil Procedure NotesDocument2 paginiRules of Court Civil Procedure NotesCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pp. v. Bulalayao, GR No. 103497, Feb. 23, 1994Document6 paginiPp. v. Bulalayao, GR No. 103497, Feb. 23, 1994Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tax Review CMTA Case Digests CompiledDocument157 paginiTax Review CMTA Case Digests CompiledCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gullas V Philippine National BankDocument3 paginiGullas V Philippine National BankCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civ Rev Digest Spouses Macasaet v. MacasaetDocument3 paginiCiv Rev Digest Spouses Macasaet v. MacasaetCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cruz V Chua, G.R. No. L - 31018, November 6, 1929Document5 paginiCruz V Chua, G.R. No. L - 31018, November 6, 1929Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rockland Construction v. Mid-Pasig Land, G.R. No. 164587, February 4, 2008Document4 paginiRockland Construction v. Mid-Pasig Land, G.R. No. 164587, February 4, 2008Charmila Siplon100% (1)

- Civ Rev Digest Republic v. SantosDocument2 paginiCiv Rev Digest Republic v. SantosCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DKC Holdings V Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 118248, April 5, 2000Document6 paginiDKC Holdings V Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 118248, April 5, 2000Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tax Bar Q Compilation UST 2009-2017Document159 paginiTax Bar Q Compilation UST 2009-2017Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soledad v. Heirs of Juan LunaDocument8 paginiSoledad v. Heirs of Juan LunaCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kalaw v. RelovaDocument2 paginiKalaw v. RelovaCharmila Siplon100% (1)

- Consti Rev Digest Saguisag vs. OchoaDocument1 paginăConsti Rev Digest Saguisag vs. OchoaCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Associated Insurance v. IyaDocument2 paginiAssociated Insurance v. IyaCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civ Rev Digest Parilla v. PilarDocument2 paginiCiv Rev Digest Parilla v. PilarCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Real Property Covering Seven Parcels of Land in Favor of Her Niece Ursulina Ganuelas (Ursulina)Document4 paginiReal Property Covering Seven Parcels of Land in Favor of Her Niece Ursulina Ganuelas (Ursulina)Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V Bayabos DigestDocument1 paginăPeople V Bayabos DigestCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic vs. Cantor, G.R. No.184621, December10, 2013: FactsDocument3 paginiRepublic vs. Cantor, G.R. No.184621, December10, 2013: FactsCharmila Siplon100% (1)

- Civ Rev Digest Fullido v. GrilliDocument4 paginiCiv Rev Digest Fullido v. GrilliCharmila Siplon100% (1)

- People vs. Sergio, G.R. No. 240053, October 9, 2019 DigestDocument1 paginăPeople vs. Sergio, G.R. No. 240053, October 9, 2019 DigestCharmila Siplon100% (2)

- Arroyo Vs CA DigestDocument2 paginiArroyo Vs CA DigestCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Almerol Vs RTC DigestDocument3 paginiAlmerol Vs RTC DigestCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Usares vs. People, G.R. No. 209047, January 07, 2019 DigestDocument1 paginăUsares vs. People, G.R. No. 209047, January 07, 2019 DigestCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic v. Toledano, G.R.no.94147, June 8, 1994Document2 paginiRepublic v. Toledano, G.R.no.94147, June 8, 1994Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ilusurio Vs BildnerDocument2 paginiIlusurio Vs BildnerCharmila Siplon100% (1)

- Chi Ming Tsoi vs. Court of AppealsDocument3 paginiChi Ming Tsoi vs. Court of AppealsCharmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lagman vs. Medialdea, G.R. No. 243522, February 19, 2019 DigestDocument1 paginăLagman vs. Medialdea, G.R. No. 243522, February 19, 2019 DigestCharmila Siplon100% (2)

- Nama: Yossi Tiara Pratiwi Kelas: X Mis 1 Mata Pelajaran: Bahasa InggrisDocument2 paginiNama: Yossi Tiara Pratiwi Kelas: X Mis 1 Mata Pelajaran: Bahasa InggrisOrionj jrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pavement Design1Document57 paginiPavement Design1Mobin AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

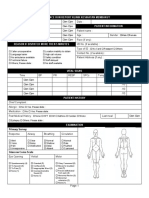

- Borang Ambulans CallDocument2 paginiBorang Ambulans Callleo89azman100% (1)

- Chapter 2 ProblemsDocument6 paginiChapter 2 ProblemsYour MaterialsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Log Building News - Issue No. 76Document32 paginiLog Building News - Issue No. 76ursindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Document6 paginiVendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Chelsea EsparagozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 5 Designing and Developing Social AdvocacyDocument27 paginiLesson 5 Designing and Developing Social Advocacydaniel loberizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mastertop 1230 Plus PDFDocument3 paginiMastertop 1230 Plus PDFFrancois-Încă nu există evaluări

- (123doc) - Toefl-Reading-Comprehension-Test-41Document8 pagini(123doc) - Toefl-Reading-Comprehension-Test-41Steve XÎncă nu există evaluări

- Waterstop TechnologyDocument69 paginiWaterstop TechnologygertjaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Person Environment Occupation (PEO) Model of Occupational TherapyDocument15 paginiThe Person Environment Occupation (PEO) Model of Occupational TherapyAlice GiffordÎncă nu există evaluări

- Richardson Heidegger PDFDocument18 paginiRichardson Heidegger PDFweltfremdheitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obesity - The Health Time Bomb: ©LTPHN 2008Document36 paginiObesity - The Health Time Bomb: ©LTPHN 2008EVA PUTRANTO100% (2)

- Technical Bulletin LXL: No. Subject Release DateDocument8 paginiTechnical Bulletin LXL: No. Subject Release DateTrunggana AbdulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mixed Up MonstersDocument33 paginiMixed Up MonstersjaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mantel Colonized Nation Somalia 10 PDFDocument5 paginiThe Mantel Colonized Nation Somalia 10 PDFAhmad AbrahamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tplink Eap110 Qig EngDocument20 paginiTplink Eap110 Qig EngMaciejÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benevisión N15 Mindray Service ManualDocument123 paginiBenevisión N15 Mindray Service ManualSulay Avila LlanosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article An Incident and Injury Free Culture Changing The Face of Project Operations Terra117 2Document6 paginiArticle An Incident and Injury Free Culture Changing The Face of Project Operations Terra117 2nguyenthanhtuan_ecoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Azimuth Steueung - EngDocument13 paginiAzimuth Steueung - EnglacothÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roleplayer: The Accused Enchanted ItemsDocument68 paginiRoleplayer: The Accused Enchanted ItemsBarbie Turic100% (1)

- Hdfs Default XML ParametersDocument14 paginiHdfs Default XML ParametersVinod BihalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Construction of Optimal Portfolio Using Sharpe's Single Index Model - An Empirical Study On Nifty Metal IndexDocument9 paginiThe Construction of Optimal Portfolio Using Sharpe's Single Index Model - An Empirical Study On Nifty Metal IndexRevanKumarBattuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter3 Elasticity and ForecastingDocument25 paginiChapter3 Elasticity and ForecastingGee JoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 13 Exercises With AnswerDocument5 paginiChapter 13 Exercises With AnswerTabitha HowardÎncă nu există evaluări

- LetrasDocument9 paginiLetrasMaricielo Angeline Vilca QuispeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proceeding of Rasce 2015Document245 paginiProceeding of Rasce 2015Alex ChristopherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Rank TestDocument3 paginiWilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Rank TestDawn Ilish Nicole DiezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stearns 87700 Series Parts ListDocument4 paginiStearns 87700 Series Parts ListYorkistÎncă nu există evaluări