Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

913 Full PDF

Încărcat de

Tiara Grhanesia DenashuryaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

913 Full PDF

Încărcat de

Tiara Grhanesia DenashuryaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

THE ANTERIOR CAPSULAR MECHANISM

IN RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER

Morphological and Clinical Studies with Special Reference to the

Glenoid Labrum and the Gleno-humeral Ligaments

H. F. MOSELEY, MONTREAL, CANADA

and

B. OVERGAARD*, KARLSTAD, SWEDEN

From the Accident Service, Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal

INTRODUCIION AND SURVEY OF THE LITERATURE

The concept of the capsular mechanism in the shoulder joint has been described by

Townley (1950) and Moseley (1959, 1961). Townley defined it as the function of the normal

capsule which allows this usually lax structure to become an effective barrier against anterior

projection of the humeral head in external rotation.

The anatomical structures which constitute these anterior and posterior capsular or

soft-tissue mechanisms respectively can be defined as follows (Fig. 1).

The anterior capsular mechanism comprises 1) the synovial membrane, capsule including the

gleno-humeral ligaments, glenoid labrum and scapular periosteum, and the related recesses

and subscapular bursa ; and 2) the subscapularis muscle and tendon with the connective

tissue arrangements to the structures listed above.

PO3TET

3u.pCcLsp1

tzZ-tl3 tt

.5-ubd-Q.1-tJ

ot:

FIG. 1

The anterior and posterior capsular mechanisms.

The posterior capsular mechanism consists of 1) the posterior capsule, synovial membrane,

labrum, periosteum, and recesses; and 2) the postero-superior cuff and the associated muscles,

which are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor.

The anterior and posterior capsular mechanisms are separated superiorly by the coraco-

humeral ligament and the long tendon of the biceps, and demarcated inferiorly by the long

tendon of the triceps.

McLaughlin and Cavallaro (1950) referred in their study of anterior dislocations of the

shoulder to the anterior and posterior pillars. Other authors have used the terms anterior

and posterior supports of the shoulder.

* Merck, Sharp and Dohme Research Fellow.

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962 913

914 H. F. MOSELEY AND B. OVERGAARD

The gleno-humeral ligaments-These three ligaments are merely slightly firmer portions of

the capsular ligaments (Codman 1934). We have found their first description in the writings

of Schlemm (1853).

The superior gleno-humeral ligament originates from the supraglenoid tubercle and the adjacent

labrum, in front of and together with the tendon of the long head of the biceps, which it

accompanies laterally to its insertion in the fovea capitis of the humerus near the tip of the

lesser tuberosity, together with a portion of the coraco-humeral ligament. As the superior

gleno-humeral ligament is accompanied by a small artery, Welcker (1876, 1877) considered it

to be a nutrition ligament of the humeral head and compared it with the round ligament

of the hip joint. Bland Sutton (1884) believed that the superior gleno-humeral ligament was

the divorced tendon ofthe subclavius, but this postulate has never been confirmed (Gardner

and Gray 1953). Delorme (1910) carried out careful anatomical dissections of these ligaments

and produced shoulder dislocations in cadavers in order to demonstrate the significance of

these check ligaments in relation to Kochers (1870) method ofreducing shoulder dislocations.

He did not attribute to the superior gleno-humeral ligament any capacity to prevent dislocation,

because this tiny ligament is, within the physiological range of movement at the gleno-humeral

joint, protected from excessive tension by the other ligaments. Furthermore, because of its

weakness, it would not be expected to be capable of checking a forcible abduction in the

gleno-humeral joint, but rather would tear immediately. DePalma, Callery and Bennett (1949)

and DePalma (1950), in their anatomical study of ninety-six shoulder specimens, found the

superior gleno-humeral ligament to be the most constant of the three ligaments.

The middle gleno-humeral ligament was described by Delorme as a very dense ligament, usually

one to two centimetres in width and up to four millimetres in thickness. DePalma et al. found

it to be a structure of considerable variability ; it was poorly defined or absent in nearly one-

third of their specimens. When the ligament is present it originates from the supraglenoid

tubercle, from the labrumjust below the superior gleno-humeral ligament, or from the scapular

neck. It extends laterally and distally towards its insertion on the lesser tuberosity, and it is

fused with the posterior aspect of the subscapularis tendon in its distal half.

The inferior gleno-humeral ligament reinforces the capsular area between the subscapularis and

the origin of the long head of the triceps. It is triangular in shape, arising from the antero-

inferior labrum and continuing distally to the surgical neck and to the medial border of the

lesser tuberosity of the humerus. Fick (1910) frequently found it to be merely a diffuse

thickening of the antero-inferior

part of the capsule. Delorme was of the opinion that this

ligament, though variable in thickness, was always well developed and up to four millimetres

thick. De Palma et a!., however, only found it to be a well defined ligament in a little

more than half of their series ; in the remaining specimens it was poorly defined or absent.

In addition to

above-mentioned the ligaments, Delorme described a system of fibres

passing between that part of the posterior surface of the subscapularis tendon which joins the

middle gleno-humeral ligament, and the origin of the long head of the triceps. Thus the fibres,

the fasciculus obliquus, pass downwards over the anterior aspect of the capsule. Strasser

(1917) called these fibres ascending fibres. Recently they have been recognised by Landsmeer

and Meyers (1959) who could trace this longitudinal-oblique system down to the glenoid

labrum and to the fascial envelope of the subscapularis tendon.

The function of the gleno-humeral ligaments is usually described as the limitation of

lateral rotation at the gleno-humeral joint ; and so they act as checkreins. From his experiments

on cadavers, however, Delorme made a closer analysis of the function of each individual

ligament. He found that the middle gleno-humeral ligament goes into action when the arm

is externally [laterally] rotated or dorsally flexed and is in a dependent or slightly abducted

position, as, for instance, when holding out the arm in order to execute a flinging movement.

If the abduction is increased coincidentally with external rotation the check of the inferior

gleno-humeral ligament will start, and thus its upper fibres will tighten more at slight abduction,

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER 915

while the check will be performed by the whole ligament in the mid-way position. When the

externally rotated arm is elevated in anterior flexion (ventropulsion), this movement will soon

be checked by the fasciculus obliquus.

The clinical importance of these ligaments has recently been stressed by McLaughlin

(1960), who wrote: The sole inelastic defence against forward displacement of the humerus

from the glenoid is the triangular sling formed by the gleno-humeral ligaments. He reported

three cases with unsuccessful Bankart-type repairs for damaged glenoid labra, where at the

time of re-operation these repairs were intact despite further dislocations. Careful inspection

of the anterior capsular mechanism, however, revealed in one case an avulsion of the gleno-

humeral ligaments from the humerus, and in the other two cases the middle gleno-humeral

ligament was disrupted. After repair of these lesions no further dislocations occurred.

The synovial recesses-Recesses or diverticula formed by the synovial membrane of the

anterior capsular mechanism, which are significant in the etiology of recurrent dislocation,

are the subscapularis bursa (superior subscapularis recess) and the inferior (subscapularis)

recess. These have been studied by, among others, DePalma et a!., Gardner and Gray, and

Olsson (1953). The subscapularis bursa is present in most cases (80 to 89 per cent); its

opening into the joint is usually situated between the superior and the middle gleno-humeral

ligaments. The bursa extends along the superior tendinous border of the subscapularis muscle

medially towards the inferior surface of the coracoid process. Its base is also attached to the

anterior surface of the subscapularis tendon for a variable extent, on the average four

centimetres by two centimetres in the young athlete operated upon for recurrent dislocation.

The bursa extends over a similar area between the capsule and the posterior surface of the

tendon. It is in this latter synovial space that the communication with the joint is found.

Thus the bursal arrangement acts as a gliding mechanism for the upper border of the

subscapularis and the coracoid process. In one of Olssons specimens the subscapularis

bursa extended as far as eight centimetres, the mean depth being approximately four

centimetres, measured along the upper margin of the tendon from the upper corner of the

lesser tuberosity.

The opening of the inferior recess is situated between the middle and the inferior gleno-

humeral ligaments. Occasionally, when the middle gleno-humeral ligament is absent, a large

synovial recess may be found above the inferior gleno-humeral ligament. In other cases there

is a complete absence of synovial recesses.

Thus it is evident that a considerable variation in the arrangement of the gleno-humeral

ligaments and the synovial recesses exists. In this connection it must be stressed that the

anterior part of the gleno-humeral fibrous joint capsule is not continuous with the glenoid

labrum in those cases where the above-mentioned synovial recesses are present. In the cases

with a large superior recess the capsule continues in the medial direction as far as the

subcoracoid region and is then reflected back on to the scapular neck and continues to the

glenoid rim. This was the arrangement in 8&6 per cent of the specimens studied by DePalma

et a!. ; in their remaining specimens the capsule was continuous with the labrum around the

entire circumference, and in those cases there were no subscapularis recesses.

The glenoid labrum*_In current text-books of anatomy this formation is invariably described

as a fibrocartilaginous structure (Gray 1958, Lanz and Wachsmuth 1959), and this definition

is also reflected in the surgical literature (Bost and Inman 1942). Its structure and function

have been compared with those of the semilunar cartilages in the knee joint, which are flexible

but constant in general form and which do not heal after tearing.

Bankart (1923, 1938) claimed that the detachment of the labrum was the essential lesion

underlying the recurrent state; this was also later accepted by Perkins (1953). Clinical

experience has shown, however, that the labrum is not invariably damaged in recurrent

Dr C. 0. Townley has been studying the histological structure of the glenoid labrum since 1950 and has found

it to consist of fibrous tissue. His unpublished information has been available to us by personal communication.

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962

916 H. F. MOSELEY AND B. OVERGAARD

dislocations, although it is in the majority of cases. Further, as shown by DePalma

et a!. (1949) and by Olsson (1953), in those decades of life in which labral detachments are

more common and severe, recurrent dislocations seldom occur. Townley (1950) removed the

anterior labrum in a dissected specimen by a posterior approach. He demonstrated that the

anterior capsular mechanism remained a functional unit and that no anterior dislocation could

be produced unless further damage was inflicted on the capsular mechanism.

Scougall (1957) showed that avulsion of the postero-inferior part of the glenoid labrum

produced experimentally in a monkey (Macaca mulatta) was capable of sound repair without

operation. Arthrography of the shoulders before the animal was killed at eight weeks showed

no leakage of the contrast medium beyond the joint confines. Histological examination of

the previously injured area showed perfect healing. He claimed that his findings should also

apply to humans.

In an attempt to elucidate some aspects of the anatomical basis for recurrent shoulder

dislocation we have carried out an anatomical, including an embryological, investigation of

the anterior capsular mechanism of the gleno-humeral joint and correlated the results with the

operative findings in a consecutive series of twenty-five cases of recurrent anterior dislocation

of the shoulder studied in detail with stereoscopic photography.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our embryological and foetal series

consists of shoulder joints from forty-

five human embryos and foetuses,

ranging in crown-rump (CR) length

from twenty-seven millimetres to term.

From the earliest embryos the upper

half of the trunk was removed in its

entirety; in the remaining foetuses the

shoulder girdles were removed and the

humeri were divided in their proximal

parts. After fixation in 10 per cent

formalin and decalcification in a mix-

ture of equal volumes of 45 per cent

formic acid and 68 per cent sodium

7

.,

formate or 50 per cent formic acid and

20 per cent sodium citrate respectively,

. FIG. 2 . the specimens were embedded in paraffin

Diagram to show levels of transverse (horizontal) sections .

through gleno-humeral joint (Figs. 3 to 6). and sectioned transversely (horizon-

tally). Sections were selected for micro-

scopical study according to Figure 2 (1, 11). Most ofthe sections were stained with haematoxylin

and eosin ; some were stained by a modified Massons method, and one by a modified

Papanicolaous stain.

In addition, seventy-five shoulder joints from cadavers were dissected in order to study

the arrangement of the gleno-humeral ligaments and the synovial recesses. Sixty-three of

these specimens came from anatomical cadavers ; the remaining twelve were fresh necropsy

specimens. Sixty-four cadavers were from subjects over fifty years of age ; the youngest was a

still-born infant, the oldest eighty-seven years. The dissections were carried out in the way

described by Schlemm (1853): the shoulder joint was opened from behind and the humeral

head resected. The anterior capsular mechanism was then studied in detail macroscopically.

In eight of the necropsy specimens the anterior glenoid labrum was removed, fixed, sectioned,

and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for microscopical study. Representative joints were

recorded in colour stereoscopic photography for repeated viewing.

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER 917

Our clinical series consists of twenty-five consecutive cases of recurrent anterior shoulder

dislocation operated upon by a modification of Bankarts procedure, including the application

of a Vitallium prosthesis on the anterior scapular neck, as described by Moseley (1947).

An anterior approach through the delto-pectoral interval is used, and the tip of the coracoid

with the coracobrachialis and the short head ofthe biceps attached to it is divided and reflected

downwards. After the abnormal laxity in the anterior capsular mechanism has been

demonstrated by forward and medial traction by a towel forceps in the tendinous tissue and

two guide sutures in the muscle belly of the subscapularis, arthrotomy is performed by dividing

the subscapularis together with the capsule at about the level of the musculo-tendinous

junction. The lesions ofthe anterior capsular mechanism which can be exposed by this approach

are then examined and recorded by colour stereoscopic photography. The postero-lateral

.-.. -. I - -

-#{149}#{149}- -

C-orc.co\.d---, -

FIG. 3

- -

---- ---1.* h.l.L:t\.

to8G The earliest specimen showing a well formed

(__.__p / }-.Q(..ci gleno-humeral joint. Embryo, 27 millimetres

3L.: 5cc..puA.ct 1.3

CR-length. Note the clearly defined anterior and

posterior labrum, giving a more fibrous im-

-- pression than does the hyaline cartilage. Note

b p trdor- I also the joint space, the biceps tendon in its

groove, thecoracoid and the subscapularis tendon.

Qko\-3 .2 Section I. (Modified Papanicolaous stain, - 28.)

notch of the humeral head, which was proved by Hermodsson (1934) to be a compression

fracture, is also examined by digital palpation and occasionally by stereoscopic photography.

The anterior glenoid labrum or its remains were excised at operation and sections were

prepared for microscopical studies in twenty-five cases, sixteen of which belonged to the present

clinical series.

Two cases of arthrodesis of the shoulder for traumatic paralysis of the brachial plexus

also provided material for this study. In one of these cases the entire glenoid labral ring was

removed and sectioned serially; in the other the anterior portion of the labrum was excised.

All the operation specimens were fixed in 10 per cent formalin, and stained in a variety of ways

with haematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome, phospho-tungstic-acid-haematoxylin, and

haematoxylin-phloxin-saffran.

RESULTS

THE GLENOID LABRUM

This structure was studied on the sections made from the embryological and foetal

material, from the necropsy material and from the specimens removed at operation. Attention

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962

918 H. F. MOSELEY AND B. OVERGAARD

was paid to the following characteristics : the appearance of the so-called labrum in different

states of rotation of the gleno-humeral joint ; its relationship to the osseous glenoid rim, to

the capsule and to the periosteum of the scapular neck, and to the hyaline cartilage of the

glenoid fossa. Further, the type of tissue constituting the labrum, the relative amount of

fibrocartilage present and its distribution, were noted.

The earliest specimen in the series that showed a clearly defined gleno-humeral joint with

a joint space was an embryo measuring twenty-seven millimetres in CR-length (Fig. 3). The

labrum seemed to be more fibrous than the hyaline cartilage, but no statement concerning the

presence of fibrocartilage could be made at this early stage. At thirty-nine millimetres

CR-length the labral tissue was still too immature to allow any definite statement of this kind,

but the histological picture resembled that of fibrous tissue with a small transition zone

: --

#{149} .

Jc)t

or*L

)

.-)pCic.c2 )

1

:

h-u.rt- -

.-

d

/.

.

%,_S_._. b.ecd

#{149}-M

Po3i: ,--,---. __i

I__i.br i:-. ,/

t(.bt t r-\ t2. .- I . AN .

Lr31LL( tv.

. Y.*)*\..* -

,p

tL3IJt\::

-. -

FIG. 4

Oblique section II of a shoulder joint

at 39 millimetres CR-length. The

posterior joint space shows well, and

the anterior joint space has just started

to develop. The labrum resembles

fibrous tissue with a small transition

zone, although the development of the

tissues has not yet reached the stage

where a definite statement could be

made. (Haematoxylin and eosin, - 30.)

towards the hyaline cartilage of the glenoid fossa. (See Figure 4, which shows a joint space

posteriorly; the anterior joint space has just started to develop.)

From our next specimen, with a CR-length of sixty-six millimetres, and on up to term,

the capsular mechanisms had a fairly consistent pattern; so one common description of the

different stages will be sufficient for our purpose.

The microscopical studies of the glenoid labrum

showed it to consist of dense fibrous

connective tissue. On the transverse sections it had

a wedge- or washer-like appearance, and

it was continuous with the capsular tissue on one side and with the periosteum ofthe scapular neck

on the other (Figs. 5 and 6). Fibrocartilage was found in all cases, but it was confined to only a

small and narrow transition zone, grading from the hyaline cartilage of the glenoid fossa into the

fibrous tissue of the capsule. The fibrocartilage was situated where the capsule, the periosteum

of the scapular neck, and the hyaline articular cartilage of the glenoid fossa meet (Fig. 6).

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER 919

Our studies also showed that the labrum was a structure which varied in its shape in

relation to the state of rotation of the humeral head. This is illustrated in Figures 5 and 6,

which show a transverse section through the anterior and the posterior capsular mechanisms

in a foetus at term, taken just below the coracoid process (Section II). The humeral head is in

medial rotation. The attachment of the capsule to the bony glenoid rim is made up of fibrous

connective tissue of the same kind as in the capsule itself, with a narrow transitional zone of

fibrocartilage at the point of the glenoid rim. Anteriorly (Fig. 5) this capsular tissue is seen

to fold up when the humeral head is in medial rotation, thus forming a washer-shaped,

functional labrum, which will straighten out and disappear if the head is rotated laterally.

- ro#{149}st)eutr\o{

-- - 5cc.pulcLr r*ciob

! --

p5l.:;:1(.. 01-1.5 )1-(

t53ti - t}Q #{149} --0d -

FIG. 5 ub5ccip / I 3

Section 11 of a gleno-humeral in a foetus joint

at term. The humeral is in medialhead

h

rotation. Shows well the typical functional

fibrous labrum, made up of folds of capsular ) I -

I

- .- *Ct*

Q-L

- . .

-

-

#{149}

- - .

- . - -

.

-

-

.

- -

-

tissue, which is heavier in this region of II , L

attachment. The labrum will straighten out

if the humeral head is laterally rotated. jout. i / -? (old5 oti ccpdc

(Modified Masson, - 15.)

5 c ti ue wEch. -w ill

- /5tL oL.* eL

Posteriorly (Fig. 6) no labrum could be seen when the posterior part of the capsule was

tight in medial rotation of the humeral head. We found the same arrangement in adult

shoulder joints.

Those labra which had been removed from necropsy specimens and those excised at

operation were also shown to consist of dense fibrous connective tissue, covered by synovial

membrane and continuous with the capsule. Fibrocartilage was also present here in the shape

of a small, narrow transition zone, as described before. In one case of arthrodesis of the

shoulder, however, the transition zone of fibrocartilage was larger, so that in some cross-

sections of the labrum up to approximately 50 per cent of the labral tissue consisted of

fibrocartilage; the rest was, as usual, made up of dense fibrous connective tissue.

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962

920 H. F. MOSELEY AND B. VERGAARD

THE GLENO-HUMERAL LIGAMENTS AND TIlE SYNOVIAL RECESSES

These were studied on the dissected anatomical and necropsy specimens.

The superior gleno-humeral ligament was found in all but two of the seventy-five specimens.

Its size was rather variable.

The middle gleno-humeral ligament was found to be a variable structure. It could be identified

in all specimens, but was poorly defined in four. It originated from the scapular neck and

?ro5 - -

t.O -owt-. - -

- -

- -- , -.

- 4

- C#{231}

FIG. 6

----

Same section

as Figure 5. It shows the 7 -

region theof posterior labrum. _*/_ crt-

Apparently there exists no labrum at all

when the posterior capsule is stretched

by the medially rotated humeral head. - {*

The fibrocartilaginous transition zone is

well shown. (Modified Masson, - 12.)

5.tOt\- zOt\cz

from the labrum, just below the origin of the superior gleno-humeral ligament. The origins

of the ligament showed all variations from being completely labral to partly labral and partly

arising from the scapular neck; and finally, arising only from the scapular neck with no

attachment to the labrum (Figs. 7 to 10). The ligament was inserted together with the

subscapularis tendon on the lesser tuberosity. The length, width and thickness of the ligament

all showed considerable variability. The ligament became tense when the arm of the cadaver

was rotated laterally and dorsally flexed when in a dependent or slightly abducted position.

This agrees with the observations of Delorme.

The inferior gleno-humeral ligatnent in our series could be identified in all cases : it was a well

formed distinct structure in sixty-nine joints; in six it was merely a diffuse thickening of the

capsule. In all cases it arose from the antero-inferior part of the labrum and blended

with the capsule between the subscapularis and the triceps. Figure 9 shows a well defined

inferior gleno-humeral ligament, a poorly defined middle gleno-humeral ligament and a large

subscapularis recess. The inferior gleno-humeral ligament was found to tighten with increasing

abduction and lateral rotation in the gleno-humeral joint; the upper fibres of the ligament

were more tense in slight abduction, the lower more tense in pronounced abduction, while

the entire ligament was active in the intermediate position.

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER 921

THE SYNOVIAL RECESSES

The size of the subscapularis bursa and the subscapularis recess showed great variability,

although the topographical arrangement of the recesses could be divided into four types (the

classification of DePalma ci a!. has been used): in Type I there is one synovial recess above

the middle gleno-humeral ligament; this was the case in five (67 per cent) of our specimens.

Type II is characterised by one synovial recess below the middle gleno-humeral ligament:

qLzt\o-hutt\.

Lq3: -

-. )

(5p FIG. 7

The anterior capsular

mechanism viewed from

within the shoulder joint

in a dissected specimen

from a woman aged eighty-

seven. The humeral head

has been removed. All

three gleno-humeral liga-

ments are well seen and

arise from the glenoid

labrum. (Type I, Fig. 10.)

-2

O3-3(L -

two (27 per cent) of our specimens were arranged in this way. In Type III there are two

synovial recesses, one above the middle gleno-humeral ligament and one below; this

arrangement was present in sixty-seven (893 per cent) of our specimens. Finally, Type IV is

characterised by one large synovial recess above the inferior gleno-humeral ligament and by

the absence of the middle gleno-humeral ligament. In one of our cases we found a large

recess of this type; the middle gleno-humeral ligament was present, however, but poorly

developed (Fig. 9).

THE CLINICAL SERIES

As previously mentioned, our clinical material consists of twenty-five consecutive cases

of recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder, repaired by a modification of Bankarts

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962

L

922 H. F. MOSELEY AND B. VERGAARD

procedure, using a Vitallium rim. The basic lesions in the anterior capsular mechanism,

which could be seen in our standard anterior approach to the shoulder, were recorded in

colour stereoscopic photography, which provided an excellent medium for further study of

these lesions. In addition, the laxity of the subscapularis muscle was demonstrated, and the

postero-lateral notch on the humeral head was palpated. The following points were noted.

.p_,.4_.. 11

- -

.-\

FIG. 8

Same view as in Figure 7. In this specimen

the middle gleno-humeral ligament is

attached partly to the labruin and partly to

the scapular neck (Type II, Fig. 10). Note

also the opening into the subscapularis bursa

and the inferior (subscapularis) recess. The

lower photograph is another view of same

specimen.

Laxity of the subscapularis muscle and tendon was demonstrable in all cases : in some

cases the tendon was also greatly attenuated and deficient inferiorly at its attachment to the

lesser tuberosity.

A postero-lateral notch of variable size in the humeral head was palpable in all cases;

it could also be demonstrated in all cases on pre-operative radiography in suitable projections.

The basic lesions of the anterior capsular mechanism, as observed after arthrotomy had

been performed, could be grouped into the following types.

The Bankart lesion-This type of lesion was present in twenty-one cases. The soft tissues-

that is, the labrum and capsule-were detached to a variable extent from the antero-inferior

bony glenoid rim. The extent of the detachment varied from one centimetre up to the entire

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER 923

anterior half of the soft-tissue attachment. The labrum was also split longitudinally in a few

cases. Fragmentation of the labrum was a common finding.

In

ten cases showing this type of lesion the periosteum of the scapular neck was also

raised as a sleeve, as described by Broca and Hartmann (1890), so that when the humeral

head dislocated into the subscapular space it pushed the capsular, labral and periosteal sleeve

tbaz 3t1Z-r-*d5 -uc3c1 c5t

Dt5QtO#{248} OG Pootli d\*cl.-

-,- -V

0a -aai

OP

3u:b3(;clp - - -

bt-t

FIG. 9

This specimen (same view as in the

previous two figures) shows a poorly

defined middle gleno-humeral ligament,

arising only from the scapular neck, thus

taking part in creating a large anterior

pouch (Type III, Fig. 10).

in front of it. It could also be demonstrated that the joint capsule and the periosteum of the

scapular neck were directly continuous with each other.

In four cases of long duration showing these lesions calcification had occurred, usually

localised at the periphery of the avulsed periosteum.

Anterior pouch with intact glenoid labrum-This arrangement was observed in four cases.

In these the soft-tissue attachment to the glenoid rim was found to be intact. There was a

large anterior pouch with synovial lining, extending up under the coracoid process. In three

of these cases the middle gleno-humeral ligament was identified, and it was found to be

attached far medially on the scapular neck, with no connection at all to the labrum; the

ligament itself including its scapular attachment also appeared intact. In this way the ligament

took part in creating the large anterior pouch which could readily accommodate the humeral

head. In the third case the middle gleno-humeral ligament was not discernible.

It should be stressed that in these four cases, as well as in all the other cases, there was

also demonstrated a postero-lateral notch in the humeral head.

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962

924 H. F. MOSELEY AND B. VERGAARD

r%.,t0ct

FIG. 10

The upper drawing shows the anterior pouch present in

Type Ill arrangement of the middle

gleno-humeral ligament. Types I, II and Ill below are diagrammatic cross-sections of the

middle gleno-humeral ligament as seen in specimens in Figures 7, 8 and 9.

DISCUSSION

Our examinations of embryological and foetal labra and of those obtained from necropsy

specimens and removed at operation revealed that the so-called labrum glenoidale was

practically devoid of fibrocartilage and was essentially made up of fibrous tissue. in only one

of eighty specimens examined was there a considerable proportion of fibrocartilage (up to

50 per cent). In all the other cases, including all the cases ofrecurrent dislocation, fibrocartilage,

as mentioned before, was confined to a small transition zone at the soft-tissue attachment on

the osseous glenoid rim : the rest of the labrum was made up of dense fibrous connective

tissue, the histological appearance of which resembled that of dense fibrous connective tissue

in general and did not resemble the appearance of the semilunar cartilage of the knee (McMillan

1961). In current text-books of histology (Greep 1954, Ham 1957, Bailey 1958, Finerty and

Cowdry 1960) fibrocartilage is defined as a combination of dense collagenous fibrous tissue

and cartilage cells, chondrocytes. The latter are enclosed in capsules and are often arranged

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER 925

in rows between which are dense bundles of collagenous fibres. This definition has been used

by us when distinguishing between hyaline cartilage, fibrocartilage and fibrous connective

tissue in order to define the fibrocartilaginous transition zone. The question concerning the

presence of fibrocartilage in the glenoid labrum during the foetal period has been a matter of

dispute. Haines (1947), for instance, reported a conspicuous fibrocartilaginous labrum at

twenty-three millimetres CR-length, and he also found the glenoid surface of the scapula to be

covered with a layer of fibrocartilage at sixty-six millimetres. Gardner and Gray (1953), in

their comprehensive study of the pre-natal development of the shoulder, could not confirm

these findings of Haines ; they were not able to find definite fibrocartilage in any shoulder

joint. However, they believed that the appearance of the area of the labrum next to the

scapula in a foetus at term suggested the appearance of fibrocartilage, the rest of the labrum

being densely fibrous.

It is also worth mentioning that Gegenbaur (quoted by Fick 1910) considered the labrum

to be part of the capsule, and Fick also pointed out that the chondrocytes were confined mainly

to the area of attachment of the labrum to the bony rim.

In conclusion, then, our studies did not show the glenoid labrum to be a consistent

structure comparable to a semilunar cartilage as is the current belief. Instead, it is evidently

a redundant fold of the capsular tissue as it attaches to the osseous glenoid rim, and it changes

its shape with different states of rotation of the humeral head, acting like a washer at the

synovial reflection at the periphery of the joint cavity in full rotation of the humeral head.

This concept is in complete agreement with that of Townley (1950, 1959), but we have not

been able to find a similar interpretation elsewhere in the literature studied.

Our dissections of necropsy specimens demonstrated the great variability in the

arrangement of the gleno-humeral ligaments and the synovial recesses of the anterior capsular

mechanism. We recognised four of the six different types of arrangement of these ligaments

and recesses described by DePalma our series was smaller

et a!. ; than theirs. In those cases

where the middle gleno-humeral ligament was poorly developed or attached a considerable

distance medially on the scapular neck with no connection at all with the labrum, an anterior

synovial pouch of variable, often considerable, size, allowing admittance of the humeral head,

was present.

It was most interesting to correlate these with the operative findings. As already

mentioned, we had in our clinical series four cases showing a completely intact soft-tissue

attachment to the anterior glenoid rim. In three of these cases the middle gleno-humeral

ligament arose well back on the scapular neck without attachment to the labrum, thus taking

part in the formation of a large anterior pouch ; in the fourth case no middle ligament could

be seen. One of these patients was a young man of pronounced asthenic habitus. His first

three displacements were spontaneously reduced subluxations which occurred without

antecedent trauma, but the last three were complete and required reduction in hospital.

There was no significant difference in the number of dislocations between the patients in this

group and those with Bankart lesions. However, we formed a definite impression that the

injuries leading to dislocation in the former group of patients were uniformly less severe

than those leading to dislocation in the other group. In addition, the dislocations in the former

group were also as a rule self-reduced, and only in rare instances was the help of a doctor

required. In this group ofcases the soft-tissue attachment to the anterior osseous rim, including

the labrum, was found intact. This pattern of post-traumatic anatomy was also noted by

McLaughlin (1960), who called it pseudo-sleeve avulsion when the subscapularis bursa

and recess are opened widely by rupture of the middle gleno-humeral ligament but the anterior

labrum and the scapular periosteum remain intact. Our investigation shows, however, how

the normal variation in the arrangement of the anatomical components of the anterior capsular

mechanism can provide the basis for such a pattern of morbid anatomy.

As mentioned before, a postero-lateral notch on the humeral head was found also in all

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962

926 H. F. MOSELEY AND B. VERGAARD

those cases which showed an intact soft-tissue attachment to the glenoid rim ; this has not to

our knowledge been previously reported in the literature.

Laxity of the subscapularis of varying degree could easily be demonstrated in all our

cases. We are, therefore, in complete disagreement with the opinion of Dickson, Humphries

and ODell (1953), who stated that laxity

of the subscapularis must remain a clinical

impression, for it is not accurately demonstrable.

SUMMARY

1 . The concept of the capsular mechanism of the shoulder joint with regard to recurrent

anterior dislocation of the shoulder has been defined and a survey of the literature presented.

2. An anatomical, including an embryological, investigation of shoulder joints with special

reference to the structure and function of the glenoid labrum and to the variations in the

arrangement of the gleno-humeral ligaments and the synovial recesses of the anterior capsular

mechanism is reported. The labrum, which is generally believed to be a consistent,

fibrocartilaginous structure, is shown to be a redundant portion of capsular tissue and a

continuation of the capsule as it attaches to the osseous glenoid rim. The fibrocartilaginous

element is confined to a small transition zone at the capsular attachment in the great majority

of cases. The great variability in the arrangement of the gleno-humeral ligaments and synovial

recesses is stressed, and it is shown that an anterior pouch of variable size is present when

the middle gleno-humeral ligament is attached to the scapular neck and not to the labrum.

3. The basic lesions of the anterior capsular mechanism found at operation for recurrent

anterior dislocation of the shoulder in twenty-five consecutive cases using a modified Bankart

procedure with a standard anterior approach to the joint are reported, and the findings are

correlated with the results of the anatomical investigation. In most cases the lesions were

found to be of the Bankart type with or without avulsion of the periosteum of the scapular

neck. In four cases, however, the soft-tissue attachment to the anterior glenoid rim was intact;

in those cases a large synovial pouch was present and the middle gleno-humeral ligament

was either not discernible or it arose from the scapular neck. In all cases a postero-lateral

notch on the humeral head was palpable and laxity ofthe subscapularis could be demonstrated.

When measured, the joint capacity was always greatly augmented.

4. The present work shows, from a basic standpoint, that Bankarts original idea that the

recurrent state was due to the failure of healing of the fractured fibrocartilaginous glenoid

labrum is no longer tenable.

5. Finally, the anomalous attachment or the insufficient development of the middle gleno-

humeral ligament in certain cases of recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation is shown to

provide the anatomical basis for the recurrent state in these cases ; this is the weak area in

the antero-inferior part of the capsule which has been described in the literature for the past

hundred years. Thus we have returned to the original view of Hippocrates.

We wish to express our gratitude to

Gardner Professor

of the Department E. of Anatomy, Wayne State

University, Detroit, for allowing us to

of his foetal use

shoulder part

material. Dr J. Langman and

Dr S. M. Banfill of the Department of Anatomy, McGill University, have kindly placed anatomical and foetal

material at our disposal. Professor G. C. McMillan, Chairman of the Department of Pathology, McGill

University, has Spent considerable time in assisting us with the microscopical studies for which we are greatly

indebted to him.

REFERENCES

BAILEYS Textbook ofHistology (1958): Edited by W. M. Copenhaver and D. D. Johnson. Fourteenth edition.

Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company.

BANKART, A. S. B. (1923): Recurrent or Habitual Dislocation of the Shoulder Joint. British Medical Journal,

ii, 1,132.

BANKART, A. S. B. (1938): The Pathology and Treatment of Recurrent Dislocation of the Shoulder-Joint.

British Journal of Surgery, 26, 23.

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER 927

BOST, F. C., and INMAN, V. T. (1942): The Pathological Changes in Recurrent Dislocation of the Shoulder.

Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 24, 595.

BROCA, A., and HARTMANN, H. (1890): Contribution a I#{233}tude

des luxations de l#{233}paule.Bulletins de la Soci#{233}t#{233}

Anatomique de Paris, 5me S#{233}rie,4, 312.

BROCA, A., and HARTMANN, H. (1890): Contribution a l#{233}tudedes luxations de l#{233}paule (Luxations anciennes,

luxations r#{233}cidivantes). Bulletins de Ia Soci#{233}t#{233}

Anatomique de Paris, 5me S#{233}rie,

4, 416.

CODMAN, E. A. (1934): The Shoulder, p. 12. Boston : The Author.

DELORME (1910): Die Hemmungsbander des Schultergelenks und ihre Bedeutung f#{252}r

die Schulterluxationen.

Archivfur Kllnische Chfrurgie, 92, 79.

DEPALMA, A. F. (1950): Surgery oft/ic Shoulder. Philadelphia : J. B. Lippincott Company.

DEPALMA, A. F., CALLERY, G., and BENNETT, G. A. (1949): Variational Anatomy and Degenerative Lesions of

the Shoulder Joint. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Instructional Course Lectures, 6, 255.

DICKSON, J. A., HUMPHRIES, A. W., and ODELL, H. W. (1953): Recurrent Dislocation ofthe Shoulder. Edinburgh:

E. & S. Livingstone Ltd. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company.

FICK, R. (1910): Handbuch der Anatomie und Mechanik der Gelenke. In v. BARDELEBEN: Handbuch der

Anatomic des Menschen. Vol. 2, Sect. 1, Part I, pp. 163-187. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

FINERTY, J. C., and COWDRY, E. V. (1960): A Textbook ofHistology. Fifth edition. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

GARDNER, E., and GRAY, D. J. (1953): Prenatal Development of the Human Shoulder and Acromioclavicular

Joints. American Journal ofAnatomy, 92, 219.

GEGENBAUR: Quoted by Fick (1910).

GRAYS ANATOMY (1958): Thirty-second edition. Edited by Johnston, T. B., Davies, D. V., and Davies, F.

London: Longmans, Green and Co.

GREEP, R. 0. (1954): Histology. New York: Blakiston.

HAINES, R. W. (1947): The Development of Joints. Journal ofAnatomy, 81, 33.

HAM, A. W. (1957): Histology. Third edition. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company.

HERMODSSON, I. (1934): Rontgenologische Studien Uber die traumatischen und habituellen Schultergelenk-

verrenkungen nach vorn und nach (Stockholm),

unten. Supplementum

Acta Radiologica 20. English

edition, edited by Moseley, H. F., and Overgaard, B., to be published by McGill University Press.

HIPPOCRATES (1927): Works. With an English translation by W. H. S. Jones and E. T. Withington. London:

William Heinemann Limited.

KOCHER, T. (1 870): Eine neue Reductionsmethode f#{252}r

Schulterverrenkung. Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift,

7, 101.

LANDSMEER, J. M. F., and MEYERS, K. A. E. (1959): The Shoulder Region Exposed by Anatomical Dissection.

Archivum Chirurgicum Neerlandicum, 11, 274.

LANZ, T. von, and WACHSMUTH, W. (1959): Praktische Anatomic. Zweite Aullage, Band 1/3, p. 101. Berlin:

Julius Springer.

MCLAUGHLIN, H. L. (1960): Recurrent Anterior Dislocation of the Shoulder. I. Morbid Anatomy. American

Journal of Surge,;, 99, 628.

MCLAUGHLIN, H. L., and CAVALLARO, W. U. (1950): Primary Anterior Dislocation ofthe Shoulder. American

Journal of Surgery, 80, 615.

MCMILLAN, G. C. (1961) : Personal communication.

MOSELEY, H. F. (1947): The Use ofa Metallic Glenoid Rim in Recurrent Dislocation ofthe Shoulder. Canadian

Medical Association Journal, 56, 320.

MOSELEY, H. F. (1959): Athletic Injuries to the Shoulder Region. American Journal ofSurgery, 98, 401.

MOSELEY, H. F. (1961): Recurrent Dislocation ofthe Shoulder. Montreal: McGill University Press. Edinburgh

and London: E. & S. Livingstone Ltd.

OLSSON, 0. (1953): Degenerative Changes of the Shoulder Joint and Their Connection with Shoulder Pain.

Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica, Supplementum 181.

PERKINS, G. (1953): Rest and Movement. Journal ofBone andJoint Surgery, 35-B, 521.

SCHLEMM, F. (1853): Ueber die Verstarkungsbander am Schultergelenk. Archiv f#{252}rAnatomic, Physiologic und

Wissenschaftliche Medicin, p. 45.

SCOUGALL, S. (1957): Posterior Dislocation of the Shoulder. Journal ofBone andJoint Surgery, 39-B, 726.

STRASSER, H. (1917): Lehrbuch der Muskel- und Gelenkmechanik. Berlin : Julius Springer.

SUTTON, J. B. (1884): On the Nature

of Ligaments (Part II). Journal ofAnatomy and Physiology, 19, 27.

TOWNLEY, C. 0.The Capsular(1950): Mechanism in Recurrent Dislocation of the Shoulder. Journal of Bone

and Joint Surgery, 32-A, 370.

TOWNLEY, C. 0. (1959) : Personal communication.

WELCKER, H. (1876): Ueber das HUftgelenk, nebst einigen Bemerkungen Ober Gelenke uberhaupt, insbesondere

Uber das Schultergelenk. Zeitschrift f#{252}r

Anatomic und Entwicklungsgeschichte, 1, 41.

WELCKER, H. (1877): Nachweis eines ligamentum interarticulare ( teres ) humeri, sowie eines hg. teres

sessile femoris. Zeitschrift f#{252}rAnatomic und Entwicklungsgeschichte, 2, 98.

VOL. 44 B, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 1962

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

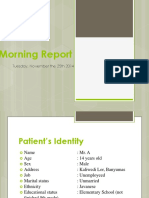

- Morning Report 24 November 2014Document53 paginiMorning Report 24 November 2014Tiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morning Report 21 November 2014Document54 paginiMorning Report 21 November 2014Tiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morning Report 25 NovemberDocument57 paginiMorning Report 25 NovemberTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise Is A Type of Physical Activity Consisting of Planned, Structured, and Repetitive BodilyDocument3 paginiExercise Is A Type of Physical Activity Consisting of Planned, Structured, and Repetitive BodilyTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Referat Sarkopenia Pada GeriatriDocument2 paginiReferat Sarkopenia Pada GeriatriTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accepted Manuscript: YprrvDocument27 paginiAccepted Manuscript: YprrvTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harris SDocument2 paginiHarris STiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peptic Ulcer Bleeding Risk. The Role of Helicobacter: Pylori Infection in NSAID/Low-Dose Aspirin UsersDocument1 paginăPeptic Ulcer Bleeding Risk. The Role of Helicobacter: Pylori Infection in NSAID/Low-Dose Aspirin UsersTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hyponatremia in Children With Acute Respiratory Infections: A ReappraisalDocument6 paginiHyponatremia in Children With Acute Respiratory Infections: A ReappraisalTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oral Ondansetron For Gastroenteritis in A Pediatric Emergency DepartmentDocument8 paginiOral Ondansetron For Gastroenteritis in A Pediatric Emergency DepartmentTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The God Helmet PDFDocument5 paginiThe God Helmet PDFTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Chemistry: Lijun You, Mouming Zhao, Joe M. Regenstein, Jiaoyan RenDocument7 paginiFood Chemistry: Lijun You, Mouming Zhao, Joe M. Regenstein, Jiaoyan RenTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- I. Patient IdentityDocument20 paginiI. Patient IdentityTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 913 Full PDFDocument15 pagini913 Full PDFTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vol. 107, No. 4, 1982 August 31, 1982 Biochemical and Biophysical Research CommunicationsDocument8 paginiVol. 107, No. 4, 1982 August 31, 1982 Biochemical and Biophysical Research CommunicationsTiara Grhanesia DenashuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Aves de Los Humedales de La Región Callao - Actualización y Estados de ConservaciónDocument26 paginiAves de Los Humedales de La Región Callao - Actualización y Estados de Conservaciónjrg_jamesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Comprehension - AntsDocument1 paginăReading Comprehension - AntsAkira CyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 001-111 mmv76 Gomon Choerodon 7 WebDocument111 pagini001-111 mmv76 Gomon Choerodon 7 WebM DayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9 - Report & NarrativeDocument1 pagină9 - Report & NarrativeTri WahyuningsihÎncă nu există evaluări

- IBO 2012 Biology OlympiadDocument49 paginiIBO 2012 Biology OlympiadAbhinav ShuklaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phylum Chordata TransesDocument2 paginiPhylum Chordata TransesMaribel Ramos InterinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 Mora y Robinson Loxocemus - LepidochelysDocument2 pagini2 Mora y Robinson Loxocemus - LepidochelysJosé MoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Embryology of Head Face &oral CavityDocument71 paginiEmbryology of Head Face &oral CavitySaleh Alsadi100% (3)

- 201 - The Saggy Baggy Elephant - See, Hear, ReadDocument28 pagini201 - The Saggy Baggy Elephant - See, Hear, ReadAndrew RukinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab Iii - Poriferans and Cnidarians ExerciseDocument3 paginiLab Iii - Poriferans and Cnidarians ExerciseAnonymous DVZFuhkPaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cnidaria - Radiate Animals: HydrozoaDocument6 paginiCnidaria - Radiate Animals: Hydrozoafitness finesseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rekap Guru DiknasDocument2.720 paginiRekap Guru DiknasVivi Vivon0% (1)

- MLTDocument20 paginiMLTSai SridharÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 1Document14 pagini4 1md.wahiduzzamanjewel412Încă nu există evaluări

- Apg IiiDocument17 paginiApg IiilokoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bio205 Lab Report PDFDocument8 paginiBio205 Lab Report PDFjonahbsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Susumu Ohno (Auth.) - Evolution by Gene Duplication-Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1970)Document171 paginiDr. Susumu Ohno (Auth.) - Evolution by Gene Duplication-Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1970)Ehab Kardouh100% (1)

- Sri Chaitanya ZoologyDocument3 paginiSri Chaitanya ZoologypullaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nest Box Dimensions From "Woodworking For Wildlife" by Carrol L. HendersonDocument1 paginăNest Box Dimensions From "Woodworking For Wildlife" by Carrol L. HendersonSanjeev ChoudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- PPSC Lecturer Zoology Mcqs DAta - UpdatedDocument9 paginiPPSC Lecturer Zoology Mcqs DAta - Updatedmashwani82Încă nu există evaluări

- Hygiene Que. BSS 1) What Are Insects?Document2 paginiHygiene Que. BSS 1) What Are Insects?Amaresh JhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bio. Sci. 2 - Course ProjectDocument3 paginiBio. Sci. 2 - Course ProjectJahzel JacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal Bhsa Inggris Kls 2Document3 paginiSoal Bhsa Inggris Kls 2Saidah saidahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 11 Unit 1 Diversity in Living Organism Ch-1,2 (Plant and Animal Kingdom) NotesDocument18 paginiClass 11 Unit 1 Diversity in Living Organism Ch-1,2 (Plant and Animal Kingdom) NotesDhana Varshini maths biologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guppy WikiDocument11 paginiGuppy Wikiglh00Încă nu există evaluări

- Biology - The Genetics of Parenthood AnalysisDocument2 paginiBiology - The Genetics of Parenthood Analysislanichung100% (5)

- Comprehension TestDocument3 paginiComprehension TestDentisak DokchandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prawn CultureDocument26 paginiPrawn CulturePreetGill67% (3)

- Carpophilus Keys For Identification of Carpophilus PDFDocument41 paginiCarpophilus Keys For Identification of Carpophilus PDFErica Livea100% (3)

- Indo-Malayan Stingless BeesDocument32 paginiIndo-Malayan Stingless BeesAbu Hassan JalilÎncă nu există evaluări