Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Guidelines For Management of Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

Încărcat de

tjelongTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Guidelines For Management of Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

Încărcat de

tjelongDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journal of the American College of Cardiology Vol. 60, No.

24, 2012

2012 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association, Inc. ISSN 0735-1097/$36.00

Published by Elsevier Inc. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.012

PRACTICE GUIDELINE

2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline

for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on

Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery,

Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions,

and Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Writing Stephan D. Fihn, MD, MPH, Chair Michael J. Mack, MD*#

Committee Julius M. Gardin, MD, Vice Chair* Mark A. Munger, PHARMD*

Members*

Richard L. Prager, MD#

Jonathan Abrams, MD Joseph F. Sabik, MD***

Kathleen Berra, MSN, ANP* Leslee J. Shaw, PHD*

James C. Blankenship, MD* Joanna D. Sikkema, MSN, ANP-BC*

Apostolos P. Dallas, MD* Craig R. Smith, JR, MD**

Pamela S. Douglas, MD* Sidney C. Smith, JR, MD*

JoAnne M. Foody, MD* John A. Spertus, MD, MPH*

Thomas C. Gerber, MD, PHD Sankey V. Williams, MD*

Alan L. Hinderliter, MD

Spencer B. King III, MD* *Writing committee members are required to recuse themselves from

Paul D. Kligfield, MD voting on sections to which their specific relationship could apply; see

Appendix 1 for detailed information. ACP Representative. ACCF/

Harlan M. Krumholz, MD AHA Representative. PCNA Representative. SCAI Representative.

Raymond Y. K. Kwong, MD Critical care nursing expertise. #STS Representative. **AATS Repre-

sentative. ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines Liaison.

Michael J. Lim, MD*

ACCF/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures Liaison.

Jane A. Linderbaum, MS, CNP-BC

Full-text guideline available at: J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:e44 164; doi:10.1016/ Williams SV. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the

j.jacc.2012.07.013. diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of

The writing committee gratefully acknowledges the memory of James T. Dove, the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task

MD, who died during the development of this document but contributed immensely Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American

to our understanding of stable ischemic heart disease. Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association,

This document was approved by the American College of Cardiology Foun- Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic

dation Board of Trustees, American Heart Association Science Advisory and Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2564 603.

Coordinating Committee, American College of Physicians, American Association This article is copublished in Circulation.

for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Copies: This document is available on the World Wide Web sites of the American

Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons College of Cardiology (www.cardiosource.org) and American Heart Association

in July 2012. (my.americanheart.org). For copies of this document, please contact Elsevier Inc.

The American College of Cardiology Foundation requests that this document be Reprint Department, fax (212) 633-3820, e-mail reprints@elsevier.com.

cited as follows: Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, Berra K, Blankenship JC, Dallas Permissions: Modification, alteration, enhancement and/or distribution of this

AP, Douglas PS, Foody JM, Gerber TC, Hinderliter AL, King SB III, Kligfield PD, document are not permitted without the express permission of the American College

Krumholz HM, Kwong RYK, Lim MJ, Linderbaum JA, Mack MJ, Munger MA, of Cardiology Foundation. Please contact Elseviers permission department:

Prager RL, Sabik JF, Shaw LJ, Sikkema JD, Smith CR Jr, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, healthpermissions@elsevier.com/.

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2565

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

ACCF/AHA Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, FACC, FAHA, Steven M. Ettinger, MD, FACC

Task Force Chair Robert A. Guyton, MD, FACC

Members

Jonathan L. Halperin, MD, FACC, FAHA, Judith S. Hochman, MD, FACC, FAHA

Chair-Elect Sharon Ann Hunt, MD, FACC, FAHA

Alice K. Jacobs, MD, FACC, FAHA, Richard J. Kovacs, MD, FACC, FAHA

Immediate Past Chair 2009 2011 Frederick G. Kushner, MD, FACC, FAHA

Sidney C. Smith, Jr, MD, FACC, FAHA, Bruce W. Lytle, MD, FACC, FAHA

Past Chair 2006 2008 Rick A. Nishimura, MD, FACC, FAHA

E. Magnus Ohman, MD, FACC

Cynthia D. Adams, MSN, APRN-BC, Richard L. Page, MD, FACC, FAHA

FAHA Barbara Riegel, DNSC, RN, FAHA

Nancy M. Albert, PHD, CCNS, CCRN, William G. Stevenson, MD, FACC, FAHA

FAHA Lynn G. Tarkington, RN

Ralph G. Brindis, MD, MPH, MACC Clyde W. Yancy, MD, FACC, FAHA

Christopher E. Buller, MD, FACC

Former Task Force member during this writing effort.

Mark A. Creager, MD, FACC, FAHA

David DeMets, PHD

3.1.1. Resting Imaging to Assess Cardiac Structure

TABLE OF CONTENTS and Function . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2574

3.1.2. Stress Testing and Advanced Imaging in Patients

Preamble . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2566

With Known SIHD Who Require Noninvasive

Testing for Risk Assessment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2575

1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2568 3.1.2.1. RISK ASSESSMENT IN PATIENTS ABLE

TO EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2575

1.1. Methodology and Evidence Overview . . . . . . . . . . . .2568 3.1.2.2. RISK ASSESSMENT IN PATIENTS UNABLE TO

1.2. Organization of the Writing Committee . . . . . . . . . .2569 EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2576

3.1.2.3. RISK ASSESSMENT REGARDLESS OF

1.3. Document Review and Approval . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2569

PATIENTS ABILITY TO EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2577

1.4. Scope of the Guideline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2569

1.5. General Approach and Overlap With Other 3.2. Coronary Angiography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2578

Guidelines or Statements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2571 3.2.1. Coronary Angiography as an Initial Testing

1.6. Magnitude of the Problem. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2571 Strategy to Assess Risk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2578

1.7. Organization of the Guideline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2571 3.2.2. Coronary Angiography to Assess Risk After

1.8. Vital Importance of Involvement by an Initial Workup With Noninvasive Testing . . . . .2578

Informed Patient: Recommendation. . . . . . . . . . . . . .2572

4. Treatment: Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2579

2. Diagnosis of SIHD: Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . .2572

4.1. Patient Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2579

2.1. Clinical Evaluation of Patients With Chest

4.2. Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

Pain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2572

4.2.1. Risk Factor Modification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

2.1.1. Clinical Evaluation in the Initial Diagnosis of 4.2.1.1. LIPID MANAGEMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

SIHD in Patients With Chest Pain . . . . . . . . . . . .2572 4.2.1.2. BLOOD PRESSURE MANAGEMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

2.1.2. Electrocardiography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2572 4.2.1.3. DIABETES MANAGEMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

2.1.2.1. RESTING ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY

4.2.1.4. PHYSICAL ACTIVITY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

TO ASSESS RISK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2572

2.1.3. Stress Testing and Advanced Imaging for 4.2.1.5. WEIGHT MANAGEMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

Initial Diagnosis in Patients With Suspected 4.2.1.6. SMOKING CESSATION COUNSELING. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2580

SIHD Who Require Noninvasive Testing . . . . . .2572 4.2.1.7. MANAGEMENT OF PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS . . . . . . .2581

2.1.3.1. ABLE TO EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2572 4.2.1.8. ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581

2.1.3.2. UNABLE TO EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2572 4.2.1.9. AVOIDING EXPOSURE TO AIR POLLUTION . . . . . . . . . .2581

2.1.3.3. OTHER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2574 4.2.2. Additional Medical Therapy to Prevent MI

and Death . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581

3. Risk Assessment: Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2574 4.2.2.1. ANTIPLATELET THERAPY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581

4.2.2.2. BETA-BLOCKER THERAPY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581

3.1. Advanced Testing: Resting and 4.2.2.3. RENIN-ANGIOTENSIN-ALDOSTERONE BLOCKER

Stress Noninvasive Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2574 THERAPY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2566 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

4.2.2.4. INFLUENZA VACCINATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581 jointly produced guidelines in the area of cardiovascular

4.2.2.5. ADDITIONAL THERAPY TO REDUCE RISK OF MI

AND DEATH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581

disease since 1980. The ACCF/AHA Task Force on

4.2.3. Medical Therapy for Relief of Symptoms . . . . . .2581 Practice Guidelines (Task Force), charged with developing,

4.2.3.1. USE OF ANTI-ISCHEMIC MEDICATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . .2581 updating, and revising practice guidelines for cardiovascular

4.2.4. Alternative Therapies for Relief of Symptoms in

diseases and procedures, directs and oversees this effort. Writ-

Patients With Refractory Angina . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2582

ing committees are charged with regularly reviewing and

5. CAD Revascularization: Recommendations . . . . . . . .2582 evaluating all available evidence to develop balanced, patient-

centric recommendations for clinical practice.

5.1. Heart Team Approach to Revascularization

Decisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2582 Experts in the subject under consideration are selected by

5.2. Revascularization to Improve Survival . . . . . . . . . . .2582

the ACCF and AHA to examine subject-specific data and

write guidelines in partnership with representatives from

5.3. Revascularization to Improve Symptoms . . . . . . . .2584

other medical organizations and specialty groups. Writing

5.4. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Compliance and

Stent Thrombosis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2585 committees are asked to perform a literature review; weigh

the strength of evidence for or against particular tests,

5.5. Hybrid Coronary Revascularization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2585

treatments, or procedures; and include estimates of ex-

6. Patient Follow-Up: Monitoring of Symptoms pected outcomes where such data exist. Patient-specific

and Antianginal Therapy: Recommendations . . . . . .2585

modifiers, comorbidities, and issues of patient preference

that may influence the choice of tests or therapies are consid-

6.1. Clinical Evaluation, Echocardiography During

Routine, Periodic Follow-Up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2585 ered. When available, information from studies on cost is

6.2. Noninvasive Testing in Known SIHD . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2586 considered, but data on efficacy and outcomes constitute the

6.2.1. Follow-Up Noninvasive Testing in Patients With primary basis for the recommendations contained herein.

Known SIHD: New, Recurrent or Worsening In analyzing the data and developing recommendations

Symptoms, Not Consistent With Unstable and supporting text, the writing committee uses evidence-

Angina . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2586

6.2.1.1. PATIENTS ABLE TO EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2586 based methodologies developed by the Task Force (1). The

6.2.1.2. PATIENTS UNABLE TO EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2586 Class of Recommendation (COR) is an estimate of the size

6.2.1.3. IRRESPECTIVE OF ABILITY TO EXERCISE . . . . . . . . . . .2587 of the treatment effect, with consideration given to risks

6.2.2. Noninvasive Testing in Known

versus benefits in addition to evidence and/or agreement

SIHDAsymptomatic (or Stable Symptoms) . .2587

that a given treatment or procedure is or is not useful/

effective or in some situations may cause harm. The Level of

Appendix 1. Author Relationships With Industry Evidence (LOE) is an estimate of the certainty or precision

and Other Entities (Relevant) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2599 of the treatment effect. The writing committee reviews and

ranks evidence supporting each recommendation, with the

Appendix 2. Reviewer Relationships With Industry weight of evidence ranked as LOE A, B, or C according to

and Other Entities (Relevant) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2601

specific definitions that are included in Table 1. Studies are

identified as observational, retrospective, prospective, or

randomized as appropriate. For certain conditions for which

Preamble inadequate data are available, recommendations are based

on expert consensus and clinical experience and are ranked

The medical profession should play a central role in evalu- as LOE C. When recommendations at LOE C are sup-

ating the evidence related to drugs, devices, and procedures ported by historical clinical data, appropriate references

for the detection, management, and prevention of disease. (including clinical reviews) are cited if available. For issues

When properly applied, expert analysis of available data on for which sparse data are available, a survey of current

the benefits and risks of these therapies and procedures can practice among the clinicians on the writing committee is

improve the quality of care, optimize patient outcomes, and the basis for LOE C recommendations, and no references

favorably affect costs by focusing resources on the most are cited. The schema for COR and LOE is summarized in

effective strategies. An organized and directed approach to a Table 1, which also provides suggested phrases for writing

thorough review of evidence has resulted in the production recommendations within each COR. A new addition to this

of clinical practice guidelines that assist physicians in select- methodology is separation of the Class III recommendations to

ing the best management strategy for an individual patient. delineate whether the recommendation is determined to be of

Moreover, clinical practice guidelines can provide a foun- no benefit or is associated with harm to the patient. In

dation for other applications, such as performance measures, addition, in view of the increasing number of comparative

appropriate use criteria, and both quality improvement and effectiveness studies, comparator verbs and suggested phrases

clinical decision support tools. for writing recommendations for the comparative effectiveness

The American College of Cardiology Foundation of one treatment or strategy versus another have been added for

(ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have COR I and IIa, LOE A or B only.

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2567

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

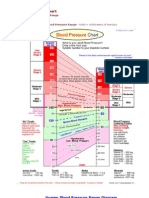

Table 1. Applying Classification of Recommendations and Level of Evidence

A recommendation with Level of Evidence B or C does not imply that the recommendation is weak. Many important clinical questions addressed in the guidelines do not lend themselves to clinical trials.

Although randomized trials are unavailable, there may be a very clear clinical consensus that a particular test or therapy is useful or effective.

Data available from clinical trials or registries about the usefulness/efficacy in different subpopulations, such as sex, age, history of diabetes, history of prior myocardial infarction, history of heart

failure, and prior aspirin use. For comparative effectiveness recommendations (Class I and IIa; Level of Evidence A and B only), studies that support the use of comparator verbs should involve direct

comparisons of the treatments or strategies being evaluated.

In view of the advances in medical therapy across the populations on the treatment effect and relevance to the

spectrum of cardiovascular diseases, the Task Force has ACCF/AHA target population to determine whether the

designated the term guideline-directed medical therapy findings should inform a specific recommendation.

(GDMT) to represent optimal medical therapy as defined by The ACCF/AHA practice guidelines are intended to assist

ACCF/AHA guideline-recommended therapies (primarily healthcare providers in clinical decision making by describing a

Class I). This new term, GDMT, will be used herein and range of generally acceptable approaches to the diagnosis,

throughout all future guidelines. management, and prevention of specific diseases or conditions.

Because the ACCF/AHA practice guidelines address The guidelines attempt to define practices that meet the needs

patient populations (and healthcare providers) residing in of most patients in most circumstances. The ultimate judg-

North America, drugs that are not currently available in ment about care of a particular patient must be made by the

North America are discussed in the text without a specific healthcare provider and patient in light of all the circumstances

COR. For studies performed in large numbers of subjects presented by that patient. As a result, situations may arise in

outside North America, each writing committee reviews the which deviations from these guidelines might be appropriate.

potential influence of different practice patterns and patient Clinical decision making should involve consideration of the

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2568 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

quality and availability of expertise in the area where care is ation for Thoracic Surgery (AATS), Preventive Cardiovascular

provided. When these guidelines are used as the basis for Nurses Association (PCNA), Society for Cardiovascular An-

regulatory or payer decisions, the goal should be improvement giography and Interventions (SCAI), and Society of Thoracic

in quality of care. The Task Force recognizes that situations Surgeons (STS), without commercial support. Writing commit-

arise in which additional data are needed to inform patient care tee members volunteered their time for this activity.

more effectively; these areas will be identified within each The recommendations in this guideline are considered

respective guideline when appropriate. current until they are superseded by a focused update or the

Prescribed courses of treatment in accordance with full-text guideline is revised. The reader is encouraged to

these recommendations are effective only if followed. consult the full-text guideline (2) for additional guidance

Because lack of patient understanding and adherence may and details about stable ischemic heart disease since the

adversely affect outcomes, physicians and other health- Executive Summary contains only the recommendations.

care providers should make every effort to engage the Guidelines are official policy of both the ACCF and AHA.

patients active participation in prescribed medical regi-

mens and lifestyles. In addition, patients should be Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, FACC, FAHA

informed of the risks, benefits, and alternatives to a Chair, ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines

particular treatment and should be involved in shared

decision making whenever feasible, particularly for COR IIa 1. Introduction

and IIb, for which the benefit-to-risk ratio may be lower.

The Task Force makes every effort to avoid actual,

1.1. Methodology and Evidence Overview

potential, or perceived conflicts of interest that may arise as

a result of industry relationships or personal interests among The recommendations listed in this document are, when-

the members of the writing committee. All writing com- ever possible, evidence based. An extensive evidence review

mittee members and peer reviewers of this guideline were was conducted as the document was compiled through

required to disclose all such current healthcare-related December 2008. Repeated literature searches were per-

relationships, as well as those existing 24 months (from formed by the guideline development staff and writing

2005) before initiation of the writing effort. The writing committee members as new issues were considered. When

committee chair may not have any relevant relationships available, current and credible meta-analyses were used

with industry or other entities (RWI); however, RWI are instead of conducting a systematic review of all primary

permitted for the vice chair position. In December 2009, the literature. New clinical trials published in peer-reviewed

ACCF and AHA implemented a new policy that requires a journals and articles through December 2011 were also

minimum of 50% of the writing committee have no relevant reviewed and incorporated when relevant. Furthermore,

RWI; in addition, the disclosure term was changed to 12 because of the extended development time period for this

months before writing committee initiation. The present guideline, peer review comments indicated that the sections

guideline was developed during the transition in RWI focused on imaging technologies required additional updat-

policy and occurred over an extended period of time. In the ing, which occurred during 2011. Therefore, the evidence

interest of transparency, we provide full information on review for the imaging sections includes published literature

RWI existing over the entire period of guideline develop- through December 2011.

ment, including delineation of relationships that expired Searches were limited to studies, reviews, and other

more than 24 months before the guideline was finalized. evidence in human subjects and published in English.

This information is included in Appendix 1. These state- Key search words included, but were not limited to:

ments are reviewed by the Task Force and all members accuracy, angina, asymptomatic patients, cardiac magnetic

during each conference call and meeting of the writing resonance (CMR), cardiac rehabilitation, chest pain, chronic

committee and are updated as changes occur. All guideline angina, chronic coronary occlusions, chronic ischemic heart

recommendations require a confidential vote by the writing disease (IHD), chronic total occlusion, connective tissue

committee and must be approved by a consensus of the disease, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) versus medical

voting members. Members who recused themselves from therapy, coronary artery disease (CAD) and exercise, coro-

voting are indicated in the list of writing committee mem- nary calcium scanning, cardiac/coronary computed tomogra-

bers, and section recusals are noted in Appendix 1. Authors phy angiography (CCTA), CMR angiography, CMR imag-

and peer reviewers RWI pertinent to this guideline are ing, coronary stenosis, death, depression, detection of CAD in

disclosed in Appendixes 1 and 2, respectively. Comprehen- symptomatic patients, diabetes, diagnosis, dobutamine stress

sive disclosure information for the Task Force is also echocardiography, echocardiography, elderly, electrocardio-

available online at http://www.cardiosource.org/ACC/ gram (ECG) and chronic stable angina, emergency depart-

About-ACC/Who-We-Are/Leadership/Guidelines-and- ment, ethnic, exercise, exercise stress testing, follow-up test-

Documents-Task-Forces.aspx. The work of the writing ing, gender, glycemic control, hypertension, intravascular

committee is supported exclusively by the ACCF, AHA, ultrasound, fractional flow reserve, invasive coronary an-

American College of Physicians (ACP), American Associ- giography, kidney disease, low-density lipoprotein lowering,

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2569

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), medication adherence, Lastly, the imaging sections were also peer reviewed separately,

minority groups, mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), after an update to that evidence base.

noninvasive testing and mortality, nuclear myocardial per- This document was approved for publication by the

fusion, nutrition, obesity, outcomes, patient follow-up, pa- governing bodies of the ACCF, AHA, ACP, AATS,

tient education, prognosis, proximal left anterior descending PCNA, SCAI, and STS.

(LAD) disease, physical activity, reoperation, risk stratifica-

tion, smoking, stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD), stable 1.4. Scope of the Guideline

angina and reoperation, stable angina and revasculariza- These guidelines are intended to apply to adult patients with

tion, stress echocardiography, radionuclide stress testing, stable known or suspected IHD, including new-onset chest

stenting versus CABG, unprotected left main, weight reduc- pain (i.e., low-risk unstable angina [UA]), or to adult

tion, and women. patients with stable pain syndromes (Figure 1). Patients

1.2. Organization of the Writing Committee who have ischemic equivalents, such as dyspnea or arm

The writing committee was composed of physicians, car- pain with exertion, are included in the latter group. Many

diovascular interventionalists, surgeons, general internists, patients with IHD can become asymptomatic with appro-

imagers, nurses, and pharmacists. The writing committee priate therapy. Accordingly, the follow-up sections of this

included representatives from the ACP, AATS, PCNA, guideline pertain to patients who were previously symptom-

SCAI, and STS. atic, including those who have undergone percutaneous

coronary intervention (PCI) or CABG.

1.3. Document Review and Approval This guideline also addresses the initial diagnostic approach

This document was reviewed by 2 external reviewers nom- to patients who present with symptoms that suggest

inated by both the ACCF and the AHA; 2 reviewers IHD, such as anginal-type chest pain, but who are not

nominated by the ACP, AATS, PCNA, SCAI, and STS; known to have IHD. In this circumstance, it is essential

and 19 content reviewers, including representatives from the that the practitioner ascertain whether such symptoms

ACCF Imaging Council, ACCF Interventional Scientific represent the initial clinical recognition of chronic stable

Council, and the AHA Council on Clinical Cardiology. All angina, reflecting gradual progression of obstructive CAD or

reviewer RWI information was collected and distributed to an increase in supply/demand mismatch precipitated by a

the writing committee and is published in this document change in activity or concurrent illness (such as anemia or

(Appendix 2). Because extensive peer review comments re- infection), or whether they represent an acute coronary

sulted in substantial revision, the guideline was subjected to a syndrome (ACS), most likely due to an unstable plaque

second peer review by all official and organizational reviewers. causing acute thrombosis. For patients with newly diagnosed

Noninvasive Asymptomatic

Testing

(SIHD)

*Features of low risk unstable angina:

Age, 70 y

Exertional pain lasting <20 min.

Pain not rapidly accelerating

Normal or unchanged ECG

No elevation of cardiac markers

Stable Angina

Asymptomatic New Onset

or Low-Risk

Persons Chest Pain

UA* Patients

(SIHD; UA/NSTEMI; STEMI)

Without (SIHD; PCI/CABG) with

Known IHD Known IHD

(CV Risk)

Noncardiac Acute Coronary

Chest Pain Syndromes

(UA/NSTEMI; STEMI;

PCI/CABG)

Sudden Cardiac Death

(VA-SCD)

Figure 1. Spectrum of IHD

Guidelines relevant to the spectrum of IHD are in parentheses.

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft; CV, cardiovascular; ECG, electrocardiogram; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SCD, sudden

cardiac death; SIHD, stable ischemic heart disease; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina; UA/NSTEMI, unstable angina/nonST-elevation myocar-

dial infarction; and VA, ventricular arrhythmia.

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2570 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

stable angina, this guideline should be used. For patients with Additionally, this guideline addresses the approach to

acute MI, the reader is referred to the ACCF/AHA guidelines asymptomatic patients with SIHD that has been diagnosed

for the management of patients with ST-elevation MI (3,4), solely on the basis of an abnormal screening study, rather than

and for patients with UA, the reader is referred to the on the basis of clinical symptoms or events such as anginal

ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients symptoms or ACS. Multiple ACCF/AHA guidelines and

With Unstable Angina/NonST-Elevation Myocardial In- scientific statements have discouraged the use of ambulatory

farction (5,5a). There are, however, patients with UA who can monitoring, treadmill testing, stress echocardiography, stress

be categorized as low risk and are addressed in this guideline myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), and computed tomog-

(Table 2). raphy scoring of coronary calcium or coronary angiography as

A key premise of this guideline is that once a diagnosis of routine screening tests in asymptomatic individuals.

IHD is established, it is necessary in most patients to assess When patients with documented IHD develop recurrent

their risk of subsequent complications, such as acute myo- chest pain, the symptoms still could be attributable to

cardial infarction or death. Because the approach to diag- another condition. Such patients are included in this guide-

nosis of suspected IHD and the assessment of risk in a line if there is sufficient suspicion that their heart disease is

patient with known IHD are conceptually different and are a likely source of symptoms to warrant cardiac evaluation.

based on different literature, these issues are addressed Just as in the case of patients with new-onset chest pain, if

separately. A clinician might, however, select a procedure for the pain seems to be cardiac in origin, the clinician must

a patient with a moderate to high pretest likelihood of IHD to determine whether such recurrent or worsening pain is

provide information for both diagnosis and risk assessment, consistent with ACS or simply represents symptoms more

whereas in a patient with a low likelihood of IHD, it could be consistent with chronic stable angina that do not require

sensible to select a test simply for diagnostic purposes without emergent attention.

regard to risk assessment. The purpose of this dichotomy is to The approach to screening and management of asymp-

promote the sensible application of appropriate testing rather tomatic patients who are at risk for IHD but who are not

than routine use of the most expensive or complex tests known to have IHD is beyond the scope of this guideline,

whether warranted or not. but it is addressed in the ACCF/AHA Guideline for

Table 2. Short-Term Risk of Death or Nonfatal MI in Patients With UA/NSTEMI

High Risk Intermediate Risk Low Risk

No high- or intermediate-risk

At least 1 of the following features must No high-risk features are present, but patient features are present, but patient

Feature be present: must have 1 of the following: may have any of the following:

History Accelerating tempo of ischemic symptoms Prior MI, peripheral or cerebrovascular disease, N/A

in preceding 48 h or CABG

Prior aspirin use

Characteristics of pain Prolonged ongoing (20 min) rest pain Prolonged (20 min) rest angina, now resolved, Increased angina frequency, severity,

with moderate or high likelihood of CAD or duration

Rest angina (20 min) or relieved with rest or Angina provoked at a lower

sublingual NTG threshold

Nocturnal angina New-onset angina with onset 2 wk to

New-onset or progressive CCS Class III or IV 2 mo before presentation

angina in previous 2 wk without prolonged

(20 min) rest pain but with intermediate or

high likelihood of CAD

Clinical findings Pulmonary edema, most likely due to Age 70 y N/A

ischemia

New or worsening mitral regurgitation

murmur

S3 or new/worsening rales

Hypotension, bradycardia, or tachycardia

Age 75 y

ECG Angina at rest with transient ST-segment T-wave changes Normal or unchanged ECG

changes 0.5 mm Pathological Q waves or resting ST-depression

Bundle-branch block, new or presumed new 1 mm in multiple lead groups (anterior,

Sustained ventricular tachycardia inferior, lateral)

Cardiac markers Elevated cardiac TnT, TnI, or CK-MB Slightly elevated cardiac TnT, TnI, or CK-MB Normal

(i.e., TnT or TnI 0.1 ng/mL) (i.e., TnT 0.01 but 0.1 ng/mL)

Estimation of the short-term risks of death and nonfatal cardiac ischemic events in UA or NSTEMI is a complex multivariable problem that cannot be fully specified in a table such as this. Therefore,

the table is meant to offer general guidance and illustration rather than rigid algorithms.

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CK-MB, creatine kinase-MB fraction; ECG, electrocardiogram; MI, myocardial

infarction; NTG, nitroglycerin; N/A, not available; TnI, troponin I; TnT, troponin T; and UA/NSTEMI, unstable angina/nonST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Modified from Braunwald et al. (7).

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2571

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk in Asymptomatic age, approximately 23% of men and 15% of women have

Adults (6). Similarly, the present guideline does not prevalent IHD, and these figures rise to 33% and 22%

apply to patients with chest pain symptoms early after among men and women 80 years of age, respectively (27).

revascularization, that is, within 6 months of revascular- Although the survival rate of patients with IHD has been

ization. steadily improving (28), it was still responsible for nearly

1.5. General Approach and Overlap With

380,000 deaths in the United States in 2010, with an

Other Guidelines or Statements

age-adjusted mortality rate of 113 per 100,000 population

(29). Although IHD is widely known to be the number 1

This guideline overlaps with numerous clinical practice cause of death in men, this is also the case for women,

guidelines published by the ACCF/AHA Task Force on among whom this condition accounts for 27% of deaths

Practice Guidelines; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood (compared with 22% due to cancer) (30). IHD also accounts

Institute; and the ACP (Table 3). To maintain consistency, for the vast majority of the mortality and morbidity of

the writing committee worked with members of other cardiac disease. Each year, 1.5 million patients have an

committees to harmonize recommendations and eliminate MI. Many more are hospitalized for UA and evaluation and

discrepancies. treatment of stable chest pain syndromes. Patients who have

This document recommends a combination of lifestyle had ACS, such as acute MI, remain at risk for recurrent

modifications and medications that constitute GDMT. events even if they have no, or limited, symptoms, and they

Recommendations for risk reduction are consistent with the should be considered to have SIHD.

AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction In approximately 50% of patients, angina pectoris is the

Therapy for Patients With Coronary and Other Vascular initial manifestation of IHD (27). The incidence of angina

Disease: 2011 Update (8). Recommendations related to rises continuously with age in women, whereas the inci-

revascularization are the result of collaboration discussions dence of angina in men peaks between 55 and 65 years of

among several writing committees, including those address- age before declining (27). It has been estimated that there

ing SIHD, PCI, CABG, and unstable angina/nonST- are 30 patients with stable angina for every patient hospi-

elevation MI. To the fullest extent possible, these guidelines

talized with infarction, and symptoms in many of these

are consistent with the appropriate use criteria documents

patients are poorly controlled (3133). The direct and

for imaging testing, diagnostic catheterization, and coronary

indirect costs of caring for patients with IHD are estimated

revascularization that are also sponsored by the ACCF

to exceed $150 billion in the United States.

(9 14).

1.6. Magnitude of the Problem 1.7. Organization of the Guideline

It is estimated that 1 in 3 adults in the United States (about The overarching framework adopted in this guideline re-

71 million) has some form of cardiovascular disease, includ- flects the complementary goals of treating patients with

ing 13 million with CAD and nearly 9 million with known SIHD, alleviating or improving symptoms, and

angina pectoris (26,27). Among persons 60 to 79 years of prolonging life. This guideline is divided into 4 basic

Table 3. Associated Guidelines and Statements

Publication

Document Reference(s) Organization Year

Guidelines

Chronic Stable Angina: 2007 Focused Update (15) ACCF/AHA 2007

Valvular Heart Disease (16) ACCF/AHA 2008

Heart Failure: 2009 Update (17) ACCF/AHA 2009

STEMI (3,4,18) ACCF/AHA 2009

Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk in Asymptomatic Adults (6) ACCF/AHA 2010

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery (19) ACCF/AHA 2011

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (20) ACCF/AHA/SCAI 2011

Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients With Coronary and (8) AHA/ACCF 2011

Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease

UA/NSTEMI: 2007 and 2012 Updates (5,5a) ACCF/AHA 2012

Statements

NCEP ATP III Implications of Recent Clinical Trials (22,23) NHLBI 2004

National Hypertension Education Program (JNC VII) (24) NHLBI 2004

Referral, Enrollment, and Delivery of Cardiac Rehabilitation/Secondary Prevention Programs at (25) AHA 2011

Clinical Centers and Beyond: A Presidential Advisory From the AHA

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; ATP III, Adult Treatment Panel 3; JNC VII, The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on

Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; and SCAI, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions.

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2572 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

sections summarizing the approaches to diagnosis, risk the patient has an interpretable ECG and at least moderate physical

assessment, treatment, and follow-up summarized in 5 functioning or no disabling comorbidity. (Level of Evidence: C)

algorithms: diagnosis (Figure 2), risk assessment (Figure 3), 2. Exercise stress with nuclear MPI or echocardiography is reasonable

GDMT (Figure 4), and revascularization (Figures 5 and 6). for patients with an intermediate to high pretest probability of

In clinical practice, steps delineated in the algorithms often obstructive IHD who have an interpretable ECG and at least moder-

overlap. An essential principle that transcends all recommen- ate physical functioning or no disabling comorbidity (4353). (Level

dations in this guideline is that of informing and involving of Evidence: B)

patients in all decisions that affect them, directly or indirectly, 3. Pharmacological stress with CMR can be useful for patients with an

as summarized in the following recommendation: intermediate to high pretest probability of obstructive IHD who have

an uninterpretable ECG and at least moderate physical functioning

1.8. Vital Importance of Involvement by an or no disabling comorbidity (50,54,55). (Level of Evidence: B)

Informed Patient: Recommendation

CLASS IIb

CLASS I

1. CCTA might be reasonable for patients with an intermediate pretest

1. Choices about diagnostic and therapeutic options should be made

probability of IHD who have at least moderate physical functioning

through a process of shared decision making involving the patient

or no disabling comorbidity (5563). (Level of Evidence: B)

and provider, with the provider explaining information about risks,

benefits, and costs to the patient. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. For patients with a low pretest probability of obstructive IHD who do

require testing, standard exercise stress echocardiography might be

reasonable, provided the patient has an interpretable ECG and at

2. Diagnosis of SIHD: Recommendations

least moderate physical functioning or no disabling comorbidity.

(Level of Evidence: C)

2.1. Clinical Evaluation of Patients With Chest Pain

CLASS III: No Benefit

2.1.1. Clinical Evaluation in the Initial Diagnosis of 1. Pharmacological stress with nuclear MPI, echocardiography, or

SIHD in Patients With Chest Pain CMR is not recommended for patients who have an interpretable

CLASS I ECG and at least moderate physical functioning or no disabling

1. Patients with chest pain should receive a thorough history and comorbidity (52,64,65). (Level of Evidence: C)

physical examination to assess the probability of IHD before addi- 2. Exercise stress with nuclear MPI is not recommended as an initial

tional testing (34). (Level of Evidence: C) test in low-risk patients who have an interpretable ECG and at least

2. Patients who present with acute angina should be categorized as moderate physical functioning or no disabling comorbidity. (Level of

stable or unstable; patients with UA should be further categorized as Evidence: C)

being at high, moderate, or low risk (5,5a). (Level of Evidence: C)

2.1.3.2. UNABLE TO EXERCISE

2.1.2. Electrocardiography

CLASS I

2.1.2.1. RESTING ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY TO ASSESS RISK

1. Pharmacological stress with nuclear MPI or echocardiography is

CLASS I recommended for patients with an intermediate to high pretest

1. A resting ECG is recommended in patients without an obvious, probability of IHD who are incapable of at least moderate physical

noncardiac cause of chest pain (3638). (Level of Evidence: B) functioning or have disabling comorbidity (43,46,47,4953). (Level

2.1.3. Stress Testing and Advanced Imaging for Initial of Evidence: B)

Diagnosis in Patients With Suspected SIHD Who CLASS IIa

Require Noninvasive Testing 1. Pharmacological stress echocardiography is reasonable for patients

See Table 4 for a summary of recommendations from this with a low pretest probability of IHD who require testing and are

section. incapable of at least moderate physical functioning or have dis-

abling comorbidity. (Level of Evidence: C)

2.1.3.1. ABLE TO EXERCISE 2. CCTA is reasonable for patients with a low to intermediate pretest

CLASS I probability of IHD who are incapable of at least moderate physical

1. Standard exercise ECG testing is recommended for patients with an functioning or have disabling comorbidity (5563). (Level of Evi-

intermediate pretest probability of IHD who have an interpretable dence: B)

ECG and at least moderate physical functioning or no disabling 3. Pharmacological stress CMR is reasonable for patients with an

comorbidity (3942). (Level of Evidence: A) intermediate to high pretest probability of IHD who are incapable of

2. Exercise stress with nuclear MPI or echocardiography is recom- at least moderate physical functioning or have disabling comorbid-

mended for patients with an intermediate to high pretest probability ity (50,54,55,6669). (Level of Evidence: B)

of IHD who have an uninterpretable ECG and at least moderate

physical functioning or no disabling comorbidity (4353). (Level of CLASS III: No Benefit

Evidence: B) 1. Standard exercise ECG testing is not recommended for patients who

CLASS IIa have an uninterpretable ECG or are incapable of at least moderate

1. For patients with a low pretest probability of obstructive IHD who do physical functioning or have disabling comorbidity (4353,58).

require testing, standard exercise ECG testing can be useful, provided (Level of Evidence: C)

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2573

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

Figure 2. Diagnosis of Patients with Suspected IHD

Colors correspond to the class of recommendations in the ACCF/AHA Table 1. The algorithms do not represent a comprehensive list of recommendations (see full guideline

text [2] for all recommendations). See Table 2 for short-term risk of death or nonfatal MI in patients with UA/NSTEMI. CCTA is reasonable only for patients with intermedi-

ate probability of IHD. CCTA indicates computed coronary tomography angiography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; ECG, electrocardiogram; Echo, echocardiography; IHD,

ischemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; Pharm, pharmacological; UA, unstable angina; and UA/NSTEMI, unstable angina/non

ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2574 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

Figure 3. Algorithm for Risk Assessment of Patients With SIHD*

*Colors correspond to the class of recommendations in the ACCF/AHA Table 1. The algorithms do not represent a comprehensive list of recommendations (see full guideline

text [2] for all recommendations). CCTA indicates coronary computed tomography angiography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; ECG, electrocardiogram; Echo, echocardi-

ography; LBBB, left bundle-branch block; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; and Pharm, pharmacological.

2.1.3.3. OTHER 3. Risk Assessment: Recommendations

CLASS IIa

1. CCTA is reasonable for patients with an intermediate pretest prob-

ability of IHD who a) have continued symptoms with prior normal 3.1. Advanced Testing: Resting and

test findings, or b) have inconclusive results from prior exercise or Stress Noninvasive Testing

pharmacological stress testing, or c) are unable to undergo stress

3.1.1. Resting Imaging to Assess Cardiac

with nuclear MPI or echocardiography (70). (Level of Evidence: C)

Structure and Function

CLASS IIb

1. For patients with a low to intermediate pretest probability of ob- CLASS I

structive IHD, noncontrast cardiac computed tomography to deter- 1. Assessment of resting left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic

mine the coronary artery calcium score may be considered (71). ventricular function and evaluation for abnormalities of myocar-

(Level of Evidence: C) dium, heart valves, or pericardium are recommended with the use

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2575

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

Figure 4. Algorithm for Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy for Patients With SIHD*

*Colors correspond to the class of recommendations in the ACCF/AHA Table 1. The algorithms do not represent a comprehensive list of recommendations (see full guideline

text [2] for all recommendations). The use of bile acid sequestrant is relatively contraindicated when triglycerides are 200 mg/dL and is contraindicated when triglycer-

ides are 500 mg/dL. Dietary supplement niacin must not be used as a substitute for prescription niacin.ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACEI,

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; ASA, aspirin, ATP III, Adult Treatment Panel 3; BP, blood pres-

sure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, JNC VII, Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on

Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LV, left ventricular; MI, myocardial infarction; NHLBI,

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and NTG, nitroglycerin.

of Doppler echocardiography in patients with known or suspected 2. Routine reassessment (1 year) of LV function with technologies

IHD and a prior MI, pathological Q waves, symptoms or signs such as echocardiography radionuclide imaging, CMR, or cardiac

suggestive of heart failure, complex ventricular arrhythmias, or an computed tomography is not recommended in patients with no

undiagnosed heart murmur (17,36,37,72,73). (Level of Evidence: B) change in clinical status and for whom no change in therapy is

contemplated. (Level of Evidence: C)

CLASS IIb

1. Assessment of cardiac structure and function with resting echocar- 3.1.2. Stress Testing and Advanced Imaging in

diography may be considered in patients with hypertension or Patients With Known SIHD Who Require

diabetes mellitus and an abnormal ECG. (Level of Evidence: C) Noninvasive Testing for Risk Assessment

2. Measurement of LV function with radionuclide imaging may be

considered in patients with a prior MI or pathological Q waves,

See Table 5 for a summary of recommendations from this

provided there is no need to evaluate symptoms or signs suggestive

section.

of heart failure, complex ventricular arrhythmias, or an undiagnosed 3.1.2.1. RISK ASSESSMENT IN PATIENTS ABLE TO EXERCISE

heart murmur. (Level of Evidence: C)

CLASS I

CLASS III: No Benefit 1. Standard exercise ECG testing is recommended for risk assess-

1. Echocardiography, radionuclide imaging, CMR, and cardiac com- ment in patients with SIHD who are able to exercise to an

puted tomography are not recommended for routine assessment of adequate workload and have an interpretable ECG (41,45,7482).

LV function in patients with a normal ECG, no history of MI, no (Level of Evidence: B)

symptoms or signs suggestive of heart failure, and no complex 2. The addition of either nuclear MPI or echocardiography to stan-

ventricular arrhythmias. (Level of Evidence: C) dard exercise ECG testing is recommended for risk assessment in

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2576 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

Figure 5. Algorithm for Revascularization to Improve Survival of Patients With SIHD*

*Colors correspond to the class of recommendations in the ACCF/AHA Table 1. The algorithms do not represent a comprehensive list of recommendations (see full guideline

text [2] for all recommendations).

patients with SIHD who are able to exercise to an adequate CLASS III: No Benefit

workload but have an uninterpretable ECG not due to left bundle- 1. Pharmacological stress imaging (nuclear MPI, echocardiography, or

branch block or ventricular pacing (8387,117119). (Level of CMR) or CCTA is not recommended for risk assessment in patients

Evidence: B) with SIHD who are able to exercise to an adequate workload and

have an interpretable ECG. (Level of Evidence: C)

CLASS IIa

1. The addition of either nuclear MPI or echocardiography to standard 3.1.2.2. RISK ASSESSMENT IN PATIENTS UNABLE TO EXERCISE

exercise ECG testing is reasonable for risk assessment in patients

with SIHD who are able to exercise to an adequate workload and CLASS I

have an interpretable ECG (8897). (Level of Evidence: B) 1. Pharmacological stress with either nuclear MPI or echocardiogra-

2. CMR with pharmacological stress is reasonable for risk assessment phy is recommended for risk assessment in patients with SIHD who

in patients with SIHD who are able to exercise to an adequate are unable to exercise to an adequate workload regardless of

workload but have an uninterpretable ECG (97102). (Level of interpretability of ECG (8386,105108). (Level of Evidence: B)

Evidence: B)

CLASS IIa

CLASS IIb 1. Pharmacological stress CMR is reasonable for risk assessment in

1. CCTA may be reasonable for risk assessment in patients with SIHD patients with SIHD who are unable to exercise to an adequate

who are able to exercise to an adequate workload but have an workload regardless of interpretability of ECG (98102,109). (Level

uninterpretable ECG (103,104). (Level of Evidence: B) of Evidence: B)

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2577

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

Figure 6. Algorithm for Revascularization to Improve Symptoms of Patients With SIHD*

*Colors correspond to the class of recommendations in the ACCF/AHA Table 1. The algorithms do not represent a comprehensive list of recommendations (see full guideline

text [2] for all recommendations). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

2. CCTA can be useful as a first-line test for risk assessment in patients larization of known coronary stenosis of unclear physiological sig-

with SIHD who are unable to exercise to an adequate workload nificance (84,96,111,112). (Level of Evidence: B)

regardless of interpretability of ECG (104). (Level of Evidence: C) CLASS IIa

1. CCTA can be useful for risk assessment in patients with SIHD who have an

indeterminate result from functional testing (104). (Level of Evidence: C)

3.1.2.3. RISK ASSESSMENT REGARDLESS OF PATIENTS ABILITY TO EXERCISE

CLASS IIb

CLASS I 1. CCTA might be considered for risk assessment in patients with SIHD

1. Pharmacological stress with either nuclear MPI or echocardiogra- unable to undergo stress imaging or as an alternative to invasive

phy is recommended for risk assessment in patients with SIHD who coronary angiography when functional testing indicates a moderate- to

have left bundle-branch block on ECG, regardless of ability to high-risk result and knowledge of angiographic coronary anatomy is

exercise to an adequate workload (105108,110). (Level of Evi- unknown. (Level of Evidence: C)

dence: B) CLASS III: No Benefit

2. Either exercise or pharmacological stress with imaging (nuclear 1. A request to perform either a) more than 1 stress imaging study or b) a

MPI, echocardiography, or CMR) is recommended for risk assess- stress imaging study and a CCTA at the same time is not recommended

ment in patients with SIHD who are being considered for revascu- for risk assessment in patients with SIHD. (Level of Evidence: C)

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2578 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

Table 4. Stress Testing and Advanced Imaging for Initial Diagnosis in Patients With Suspected SIHD

Who Require Noninvasive Testing

Exercise ECG

Status Interpretable Pretest Probability of IHD

Test Able Unable Yes No Low Intermediate High COR LOE References

Patients able to exercise*

Exercise ECG X X X I A (3942)

Exercise with nuclear MPI or Echo X X X X I B (4353)

Exercise ECG X X X IIa C N/A

Exercise with nuclear MPI or Echo X X X X IIa B (4353)

Pharmacological stress CMR X X X X IIa B (50,54,55)

CCTA X Any X IIb B (5563)

Exercise Echo X X X IIb C N/A

Pharmacological stress with nuclear X X Any III: No Benefit C (52,64,65)

MPI, Echo, or CMR

Exercise stress with nuclear MPI X X X III: No Benefit C N/A

Patients unable to exercise

Pharmacological stress with nuclear X Any X X I B (43,46,47,4953)

MPI or Echo

Pharmacological stress Echo X Any X IIa C N/A

CCTA X Any X X IIa B (5563)

Pharmacological stress CMR X Any X X IIa B (50,54,55,6669)

Exercise ECG X X Any III: No Benefit C (4353,58)

Other

CCTA Any Any X IIa C (70)

If patient has any of the following:

a) Continued symptoms with prior

normal test, or

b) Inconclusive exercise or

pharmacological stress, or

c) Unable to undergo stress with MPI

or Echo

CAC score Any Any X IIb C (71)

*Patients are candidates for exercise testing if they are capable of performing at least moderate physical functioning (i.e., moderate household, yard, or recreational work and most activities of daily

living) and have no disabling comorbidity. Patients should be able to achieve 85% of age-predicted maximum heart rate.

CAC indicates coronary artery calcium; CCTA, cardiac computed tomography angiography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; COR, class of recommendation; ECG, electrocardiogram; Echo,

echocardiography; IHD, ischemic heart disease; LOE, level of evidence; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; N/A, not available, and SIHD, stable ischemic heart disease.

3.2. Coronary Angiography CLASS IIa

1. Coronary angiography is reasonable to further assess risk in pa-

3.2.1. Coronary Angiography as an Initial Testing tients with SIHD who have depressed LV function (ejection fraction

Strategy to Assess Risk 50%) and moderate risk criteria on noninvasive testing with

demonstrable ischemia (137139). (Level of Evidence: C)

CLASS I

2. Coronary angiography is reasonable to further assess risk in pa-

1. Patients with SIHD who have survived sudden cardiac death or

tients with SIHD and inconclusive prognostic information after

potentially life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia should undergo

noninvasive testing or in patients for whom noninvasive testing is

coronary angiography to assess cardiac risk (121123). (Level of

contraindicated or inadequate. (Level of Evidence: C)

Evidence: B)

3. Coronary angiography for risk assessment is reasonable for

2. Patients with SIHD who develop symptoms and signs of heart failure

patients with SIHD who have unsatisfactory quality of life due to

should be evaluated to determine whether coronary angiography

angina, have preserved LV function (ejection fraction 50%), and

should be performed for risk assessment (124127). (Level of

have intermediate risk criteria on noninvasive testing (140,141).

Evidence: B)

(Level of Evidence: C)

3.2.2. Coronary Angiography to Assess Risk After CLASS III: No Benefit

Initial Workup With Noninvasive Testing 1.

Coronary angiography for risk assessment is not recommended in

CLASS I patients with SIHD who elect not to undergo revascularization or

1. Coronary arteriography is recommended for patients with SIHD who are not candidates for revascularization because of comorbidi-

whose clinical characteristics and results of noninvasive testing ties or individual preferences (140,141). (Level of Evidence: B)

indicate a high likelihood of severe IHD and when the benefits are 2. Coronary angiography is not recommended to further assess risk in

deemed to exceed risk (38,72,128136). (Level of Evidence: C) patients with SIHD who have preserved LV function (ejection frac-

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2579

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

Table 5. Using Stress Testing and Advanced Imaging for Patients With Known SIHD Who Require Noninvasive Testing for Risk

Assessment

Exercise ECG

Status Interpretable

Test Able Unable Yes No COR LOE References Additional Considerations

Patients able to exercise*

Exercise ECG X X I B (41,45,7482)

Exercise with nuclear MPI or X X I B (8387,117119) Abnormalities other than LBBB or

Echo ventricular pacing

Exercise with nuclear MPI or X X IIa B (8897)

Echo

Pharmacological stress CMR X X IIa B (97102)

CCTA X X IIb B (103,104)

Pharmacological stress X X III: No Benefit C N/A

imaging (nuclear MPI, Echo,

CMR) or CCTA

Patients unable to exercise

Pharmacological stress with X Any I B (8386,105108)

nuclear MPI or Echo

Pharmacological stress CMR X Any IIa B (98102,109)

CCTA X Any IIa C (104) Without prior stress test

Regardless of patients ability to exercise

Pharmacological stress with Any X I B (105108,110) LBBB present

nuclear MPI or Echo

Exercise/pharmacological Any Any I B (84,96,111,112) Known coronary stenosis of unclear

stress with nuclear MPI, physiological significance being

Echo, or CMR considered for revascularization

CCTA Any Any IIa C N/A Indeterminate result from

functional testing

CCTA Any Any IIb C N/A Unable to undergo stress imaging

or as alternative to coronary

catheterization when functional

testing indicates moderate to

high risk and angiographic

coronary anatomy is unknown

Requests to perform multiple Any Any III: No Benefit C N/A

cardiac imaging or stress

studies at the same time

CCTA indicates cardiac computed tomography angiography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; COR, class of recommendation; ECG, electrocardiogram; Echo, echocardiography; LBBB, left

bundle-branch block; LOE, level of evidence; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; and N/A, not available.

*Patients are candidates for exercise testing if they are capable of performing at least moderate physical functioning (i.e., moderate household, yard, or recreational work and most activities of daily

living) and have no disabling comorbidity. Patients should be able to achieve 85% of age-predicted maximum heart rate.

tion 50%) and low-risk criteria on noninvasive testing (140,141). b. an explanation of medication management and cardiovascular

(Level of Evidence: B) risk reduction strategies in a manner that respects the patients

3. Coronary angiography is not recommended to assess risk in pa- level of understanding, reading comprehension, and ethnicity

tients who are at low risk according to clinical criteria and who have (8,145149) (Level of Evidence: B);

not undergone noninvasive risk testing. (Level of Evidence: C) c. a comprehensive review of all therapeutic options (8,146149)

4. Coronary angiography is not recommended to assess risk in asymp- (Level of Evidence: B);

tomatic patients with no evidence of ischemia on noninvasive d. a description of appropriate levels of exercise, with encourage-

testing. (Level of Evidence: C) ment to maintain recommended levels of daily physical activity

(8,150153) (Level of Evidence: C);

4. Treatment: Recommendations e. introduction to self-monitoring skills (150,152,153) (Level of

Evidence: C); and

f. information on how to recognize worsening cardiovascular symp-

4.1. Patient Education

toms and take appropriate action. (Level of Evidence: C)

CLASS I

1. Patients with SIHD should have an individualized education plan to 2. Patients with SIHD should be educated about the following lifestyle

optimize care and promote wellness, including: elements that could influence prognosis: weight control, mainte-

a. education on the importance of medication adherence for man- nance of a body mass index of 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, and mainte-

aging symptoms and retarding disease progression (142144) nance of a waist circumference less than 102 cm (40 inches) in

(Level of Evidence: C); men and less than 88 cm (35 inches) in women (less for certain

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

2580 Fihn et al. JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary December 18, 2012:2564603

racial groups) (8,145,154157); lipid management (23); blood ers, with addition of other drugs, such as thiazide diuretics or

pressure control (24,158); smoking cessation and avoidance of expo- calcium channel blockers, if needed to achieve a goal blood pres-

sure to secondhand smoke (8,159,160); and individualized medical, sure of less than 140/90 mm Hg (203,204). (Level of Evidence: B)

nutrition, and lifestyle changes for patients with diabetes mellitus to

4.2.1.3. DIABETES MANAGEMENT

supplement diabetes treatment goals and education (161). (Level of

Evidence: C) CLASS IIa

1. For selected individual patients, such as those with a short duration

CLASS IIa of diabetes mellitus and a long life expectancy, a goal hemoglobin

1. It is reasonable to educate patients with SIHD about

A1c of 7% or less is reasonable (205207). (Level of Evidence: B)

a. adherence to a diet that is low in saturated fat, cholesterol, and

2. A goal hemoglobin A1c between 7% and 9% is reasonable for

trans fat; high in fresh fruits, whole grains, and vegetables; and

certain patients according to age, history of hypoglycemia, presence

reduced in sodium intake, with cultural and ethnic preferences

of microvascular or macrovascular complications, or presence of

incorporated (8,23,24,162,163) (Level of Evidence: B);

coexisting medical conditions (208,209). (Level of Evidence: C)

b. common symptoms of stress and depression to minimize stress-

related angina symptoms (164) (Level of Evidence: C); CLASS IIb

c. comprehensive behavioral approaches for the management of 1. Initiation of pharmacotherapy interventions to achieve target hemoglo-

stress and depression (165168) (Level of Evidence: C); and bin A1c might be reasonable (161,210219). (Level of Evidence: A)

d. evaluation and treatment of major depressive disorder when CLASS III: Harm

indicated (142,165,167,169,170,173175). (Level of Evi- 1. Therapy with rosiglitazone should not be initiated in patients with

dence: B) SIHD (220,221). (Level of Evidence: C)

4.2. Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy 4.2.1.4. PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

4.2.1. Risk Factor Modification CLASS I

1. For all patients, the clinician should encourage 30 to 60 minutes of

4.2.1.1. LIPID MANAGEMENT moderate-intensity aerobic activity, such as brisk walking, at least 5

days and preferably 7 days per week, supplemented by an increase

CLASS I

1. Lifestyle modifications, including daily physical activity and weight in daily lifestyle activities (e.g., walking breaks at work, gardening,

management, are strongly recommended for all patients with SIHD household work) to improve cardiorespiratory fitness and move

(23,176). (Level of Evidence: B) patients out of the least-fit, least-active, high-risk cohort (bottom

2. Dietary therapy for all patients should include reduced intake of 20%) (222224). (Level of Evidence: B)

saturated fats (to 7% of total calories), trans fatty acids (to 1% 2. For all patients, risk assessment with a physical activity history

of total calories), and cholesterol (to 200 mg/d) (23,177180). and/or an exercise test is recommended to guide prognosis and

(Level of Evidence: B) prescription (225228). (Level of Evidence: B)

3. In addition to therapeutic lifestyle changes, a moderate or high dose 3. Medically supervised programs (cardiac rehabilitation) and physician-

of a statin therapy should be prescribed, in the absence of contra- directed, home-based programs are recommended for at-risk patients

indications or documented adverse effects (23,163,181183). at first diagnosis (222,229, 230). (Level of Evidence: A)

(Level of Evidence: A) CLASS IIa

1. It is reasonable for the clinician to recommend complementary

CLASS IIa

resistance training at least 2 days per week (231,232). (Level of

1. For patients who do not tolerate statins, low-density lipoprotein-

Evidence: C)

cholesterollowering therapy with bile acid sequestrants,* niacin,

or both is reasonable (184,186,187). (Level of Evidence: B) 4.2.1.5. WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

4.2.1.2. BLOOD PRESSURE MANAGEMENT CLASS I

1. Body mass index and/or waist circumference should be assessed at

CLASS I every visit, and the clinician should consistently encourage weight

1. All patients should be counseled about the need for lifestyle modi- maintenance or reduction through an appropriate balance of life-

fication: weight control; increased physical activity; alcohol moder- style physical activity, structured exercise, caloric intake, and formal

ation; sodium reduction; and emphasis on increased consumption behavioral programs when indicated to maintain or achieve a body

of fresh fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products (24,188196). mass index between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 and a waist circumfer-

(Level of Evidence: B) ence less than 102 cm (40 inches) in men and less than 88 cm (35

2. In patients with SIHD with blood pressure 140/90 mm Hg or inches) in women (less for certain racial groups) (154,233241).

higher, antihypertensive drug therapy should be instituted in (Level of Evidence: B)

addition to or after a trial of lifestyle modifications (197202). 2. The initial goal of weight loss therapy should be to reduce body weight

(Level of Evidence: A) by approximately 5% to 10% from baseline. With success, further

3. The specific medications used for treatment of high blood pressure weight loss can be attempted if indicated. (Level of Evidence: C)

should be based on specific patient characteristics and may include

angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and/or beta block- 4.2.1.6. SMOKING CESSATION COUNSELING

*The use of bile acid sequestrant is relatively contraindicated when triglycerides are CLASS I

200 mg/dL and is contraindicated when triglycerides are 500 mg/dL. 1. Smoking cessation and avoidance of exposure to environmental

Dietary supplement niacin must not be used as a substitute for prescription niacin. tobacco smoke at work and home should be encouraged for all

Downloaded From: http://content.onlinejacc.org/ on 03/08/2013

JACC Vol. 60, No. 24, 2012 Fihn et al. 2581

December 18, 2012:2564603 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Executive Summary

patients with SIHD. Follow-up, referral to special programs, and CLASS IIb

pharmacotherapy are recommended, as is a stepwise strategy for 1. Beta blockers may be considered as chronic therapy for all other

smoking cessation (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange, Avoid) patients with coronary or other vascular disease. (Level of Evidence: C)

(242244). (Level of Evidence: B)

4.2.2.3. RENIN-ANGIOTENSIN-ALDOSTERONE BLOCKER THERAPY

4.2.1.7. MANAGEMENT OF PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS CLASS I

1. ACE inhibitors should be prescribed in all patients with SIHD who

CLASS IIa

1. It is reasonable to consider screening SIHD patients for depression also have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, LV ejection fraction 40%

and to refer or treat when indicated (162,165,169,245248). (Level or less, or chronic kidney disease, unless contraindicated (113

of Evidence: B) 116,120). (Level of Evidence: A)

2. Angiotensin-receptor blockers are recommended for patients with

CLASS IIb SIHD who have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, LV systolic dysfunc-

1. Treatment of depression has not been shown to improve cardiovas- tion, or chronic kidney disease and have indications for, but are

cular disease outcomes but might be reasonable for its other intolerant of, ACE inhibitors (272274). (Level of Evidence: A)

clinical benefits (165,173,249). (Level of Evidence: C)

CLASS IIa

4.2.1.8. ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION 1. Treatment with an ACE inhibitor is reasonable in patients with both

SIHD and other vascular disease (275,276). (Level of Evidence: B)

CLASS IIb 2. It is reasonable to use angiotensin-receptor blockers in other pa-

1. In patients with SIHD who use alcohol, it might be reasonable for

tients who are ACE inhibitor intolerant (277). (Level of Evidence: C)

nonpregnant women to have 1 drink (4 ounces of wine, 12 ounces

of beer, or 1 ounce of spirits) a day and for men to have 1 or 2 drinks 4.2.2.4. INFLUENZA VACCINATION

a day, unless alcohol is contraindicated (such as in patients with a

CLASS I

history of alcohol abuse or dependence or with liver disease)

1. An annual influenza vaccine is recommended for patients with SIHD

(250252). (Level of Evidence: C)

(278282). (Level of Evidence: B)

4.2.1.9. AVOIDING EXPOSURE TO AIR POLLUTION

4.2.2.5. ADDITIONAL THERAPY TO REDUCE RISK OF MI AND DEATH

CLASS IIa

CLASS III: No Benefit

1. It is reasonable for patients with SIHD to avoid exposure to in- 1. Estrogen therapy is not recommended in postmenopausal women

creased air pollution to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events with SIHD with the intent of reducing cardiovascular risk or improv-

(253256). (Level of Evidence: C) ing clinical outcomes (283286). (Level of Evidence: A)

4.2.2. Additional Medical Therapy to 2. Vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta-carotene supplementation are not

recommended with the intent of reducing cardiovascular risk or

Prevent MI and Death

improving clinical outcomes in patients with SIHD (181,287291).

4.2.2.1. ANTIPLATELET THERAPY (Level of Evidence: A)

3. Treatment of elevated homocysteine with folate or vitamins B6 and

CLASS I

B12 is not recommended with the intent of reducing cardiovascular

1. Treatment with aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily should be continued

risk or improving clinical outcomes in patients with SIHD (292295).

indefinitely in the absence of contraindications in patients with SIHD

(Level of Evidence: A)

(257,258). (Level of Evidence: A)

4. Chelation therapy is not recommended with the intent of improving

2. Treatment with clopidogrel is reasonable when aspirin is contrain-

symptoms or reducing cardiovascular risk in patients with SIHD

dicated in patients with SIHD (259). (Level of Evidence: B)

(296299). (Level of Evidence: C)

CLASS IIb 5. Treatment with garlic, coenzyme Q10, selenium, or chromium is not

1. Treatment with aspirin 75 to 162 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg recommended with the intent of reducing cardiovascular risk or

daily might be reasonable in certain high-risk patients with SIHD improving clinical outcomes in patients with SIHD. (Level of Evi-

(260). (Level of Evidence: B) dence: C)

CLASS III: No Benefit 4.2.3. Medical Therapy for Relief of Symptoms