Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Frameworks For Inquiry

Încărcat de

MackeeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Frameworks For Inquiry

Încărcat de

MackeeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Consortium for Media Literacy Volume No.

53 August 2013

In This Issue

Theme: The Importance of Frameworks for Inquiry 02

Why have a framework for media literacy education? Because frameworks are

powerful tools for structuring inquiry in any field.

Research Highlights 03

We focus on the use of frameworks as tools for judgment and decision making,

and show how they embody key principles of media literacy education. We

also explore the traditional use of a conceptual framework as a tool for

scientific research.

CML News 06

A longitudinal study of CMLs Beyond Blame violence prevention curriculum

and its framework for structuring curricula was published in the online journal

Injury Prevention. The research reinforces the need for media literacy

education in schools.

Media Literacy Resources 07

In our resources section, we present a report on the prospects for media

literacy education in an unnamed European State. How much do the problems

and opportunities for media literacy in [country X] remind you

of the conditions for media literacy where you live?

Med!aLit Moments 10

In this MediaLit Moment, your middle school students will have an opportunity

to lift the veil on the construction of media by examining how magazines are

customized for audiences in different regions of the world.

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 1

Theme: The Importance of Frameworks for Inquiry

We live in a world defined by frameworks. They provide criteria for judgment and decision

making in our every day lives. Examples of durable frameworks of this type include the

Benjamin Graham Portfolio as a framework for stock market investing, the Twelve Steps as a

framework for recovery, the Ten Commandments as a framework for moral behavior. The Bill

of Rights clearly functions as a framework for judgment and decision making. Using these

frameworks can be a simple task, or intricately complex.

CMLs framework of Key Questions and Core Concepts of media literacy is a tool for

structuring exploration of any content through questioning (Shields and Tajalli, Intermediate

Theory). It helps users extend and sharpen their thinking and provides guiding principles for

decision making. The Empowerment Spiral of Awareness, Analysis, Reflection and Action is

also a part of CMLs framework for media literacy. In applying these ideas, for example, a film

goer who had never seen the framework might ask, Why was the movie so gory? With the

aid of the CML framework, that same audience member might ask, Were the producers using

the gory scenes to target a particular audience, and, upon reflection, is this what I want to

watch?

In this issue of Connections, we justify the use of a framework for media literacy education by

defining and describing what conceptual frameworks are; by providing examples of

frameworks which are indispensable to us, and by highlighting their advantages and

demonstrating their versatility. In our first research essay, we focus on the use of frameworks

as tools for judgment and decision making, and show how they embody key principles of

media literacy education. In our second essay, we discuss the traditional use of a conceptual

framework as a powerful tool for scientific research. In our resources section, we present a

brief report by a guest author on the current status and prospects for media literacy education

in an unnamed European State, and invite you to guess the State which the report describes.

And in our MediaLit Moment, your middle school students will have a chance to lift the veil on

the construction of media by examining how magazine covers are customized for audiences in

different locations.

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 2

Research Highlights

Frameworks for Judgment and Decision Making

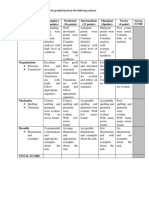

One way to illuminate the flexibility of conceptual frameworks is to classify them along a

continuum of research purposes:

Working Hypothesis A statement of expected outcomes which can be used for wide-

ranging exploration of a topic.

Categories When confronted with an entirely new problem or question, provisional

classification can be essential for understanding.

Formal Hypothesis Used to explain phenomena or predict outcomes.

Practical Ideal Type Used to develop criteria for judgment. A typical research

question might be phrased, How close is this process/policy to an ideal standard?

Models of Operations Research Used for high stakes decision making. A typical

research question might be phrased, Which project should be built?

(Adapted from Shields and Tajalli, Intermediate Theory 317 ff.).

The CML framework, Questions/QTIPS, can easily be used across most of the purposes

listed above. At least one research study has approached the framework as a theoretical

model for instruction, and utilized a formal hypothesis to determine its effectiveness.

Students and teachers using the framework tend to use a working hypothesis to extend their

examination of specific media texts. The December 2012 issue of Connections used the

framework to explicate our criteria for media literacy instruction, and our Media Literacy

Trilogy demonstrates how the framework can be used to make curriculum choices, especially

for media construction and de-construction.

Regardless of whether frameworks are used for research or for classroom practice, their use

always entails some sort of risk. Contradictory evidence can upend the most carefully

constructed theoretical framework. But, of course, research is an iterative process in which

the researcher revises her theory in an attempt to arrive at a successively more accurate

approximation of reality. In discussing student research projects utilizing a classificatory

framework, Shields observes, the explicit challenge of inventing a descriptive framework

requires a degree of intellectual independence that can make students uncomfortable (323).

In the field of media literacy education, critical autonomy is a primary goal. Careful evaluation

can lead to media choices which are still inappropriate or disappointing (for students,

teachers and parents alike!), but the practice and development of reasoned judgment holds a

greater value. Its something that a well-constructed conceptual framework implicitly

encourages.

The use of conceptual frameworks to develop reasoned judgment also explains the

importance of the term process skills. At several points in Reason and Rigor, Ravitch and

Riggan stress that a conceptual framework is not a product, but a process. For example, a

literature review should not simply summarize the literature, or simply propose a theory, but

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 3

create a dialogue between the researcher--with all his motivations and purposes--and other

authors who have addressed the topic--who have interests and commitments of their own.

Project-based learning frameworks in K-12 schools are designed to enhance this dialogue.

While projects begin with student interests, students are given opportunities to understand

and consider the interests and perspectives of community members and other researchers in

the field.

Finally, its worth noting how a framework used as a tool for inquiry can transform the inquirer.

In an academic setting Shields and Tajalli, both professors of public administration, were

highly satisfied with the outcomes for graduate students who learned how to construct

conceptual frameworks for research: They see things differently, and ask different questions

during meetings. . .Their colleagues say, You have changed. The transformation of inquiry

goes beyond the immediate task at hand and helps to create different, more capable

professionals (331).

Frameworks for Research

In several issues of Connections, weve noted the distinction between information and

knowledge. Information online may be plentiful, but schools rarely teach the intellectual

strategies needed to analyze and evaluate that information against acceptable criteria.

In a similar vein, information should be distinguished from data. Frederick Erickson, a

distinguished social science researcher, explains this way: For some years now, as I teach

participant observation research. . .Ive been saying that field notes, your stack of field notes

arent data; theyre an information source, and you discover data in them by linking pieces of

a research question, or an assertion you want to make (Ravitch and Riggan, Reason and

Rigor, 157).

A theory is needed to create data from all the information which is gathered. Drawing from

John Deweys philosophy of science, Patricia Shields and Hassan Tajalli focus attention on

the role of the researcher in constructing a theory, and argue that a theory is not so much a

statement of truth as a tool which the researcher uses to structure inquiry about a question or

problem (Intermediate Theory, 314, emphasis added).

In Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research, Sharon Ravitch and

Matthew Riggan define a conceptual framework as an argument about why the topic one

wishes to study matters, and why the means proposed to study it are appropriate and

rigorous. By argument, we mean that a conceptual framework is a series of sequenced,

logical propositions the purpose of which is to convince the reader of the studys importance

and rigor. . .by appropriate and rigorous, we mean that a conceptual framework should argue

convincingly that 1) the research questions are an outgrowth of the argument for relevance;

2) the information to be collected provide the researcher with the raw material needed to

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 4

explore the research question; and 3) the analytic approach allows the researcher to

effectively respond to (if not always answer) those questions (7).

The CML framework meets these criteria. The argument of the framework might be phrased

this way: All media are constructed, and recognizing the way in which media are

constructed is a key literacy skill. The Core Concepts are a series of sequenced, logical

propositions which argue how the construction of media texts can be recognized. Because

they are framed as a series of sequenced, inter-related and logical propositions, their validity

can be measured--as opposed to other theories of literacy which lack such a framework.

Validation requires evidence that teachers and students who have practiced with the

framework have demonstrated an increased awareness of the constructed nature of media.

Fortunately, peer-reviewed research is showing that this is the case, particularly with violent

media texts. Finally, because the framework can be used to standardize methods of

instruction, the validity of the framework can be reliably tested among different populations.

A unique facet of the CML framework is that teachers and students may be considered

researchers in their own right. In their second chapter, Ravitch and Riggan assert that

researchers who examine their own motivations, expectations and biases heighten the

effectiveness of a conceptual framework. The Empowerment Spiral, which focuses attention

on the inquirer, encourages teachers and students to ask the same kinds of questions of

themselves. And when analysis is complete, theyre encouraged to ask, why does it matter?

Asking that question is likely to spur more nuanced research. Furthermore, the framework

serves as a theory which structures inquiry for the students and teachers who use it, and

implicitly defines the methods to be used, namely, an exploration of the relationships between

producers, texts and audiences. Of course, Literacy for the 21st Century and other CML texts

also elucidate the connections between theory and method in detail.

One of the greatest advantages of a conceptual framework is its flexibility. For a formal

research proposal, a conceptual framework is used to organize the ocean of information

available in the literature on the topic, ensuring that discussion of the existing literature is

directly relevant to the questions for research. From there, the framework is used to structure

the methods by which data will be collected and measured. On a local level, the framework

can be applied to specific cases, or used to make specific policy recommendations. The

CML framework exhibits the same flexibility of scale. Critical media literacy and other sub-

fields of media studies would be impossible without the theory of media construction. In the

classroom, the theory of media construction lies behind individual practices such as close

analysis. As students learn the difference between description and interpretation, they learn

how they are actively re-constructing the text.

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 5

CML News

Longitudinal Study Published in Injury

Prevention supports media literacy education

for adolescents

Evaluation of a school-based violence prevention

media literacy curriculum was published by

Kathryn R. Fingar and Tessa Jolls in Injury

Prevention, online August 2013. The purpose of

Media literacy education is a

promising approach to mitigating the study was to evaluate whether Beyond Blame,

negative effects of media use a violence prevention media literacy curriculum, is

associated with improved knowledge, beliefs and

behaviors related to media use and aggression

and to determine the effectiveness of CMLs

approach and framework for media literacy

education.

The study, conducted by the Southern California

Injury Prevention Research Center at UCLA,

assessed the effectiveness of CMLs curriculum

Beyond Blame: Challenging Violence in the Media

throughout schools in Southern California from

2007-2008. The study followed middle school

students from one academic year to the next

assessing their ability to recognize and evaluate

violence in media along with changes in their

behavior towards violent media. Read the study

here.

About Us...

The Consortium for Media Literacy addresses the

role of global media through the advocacy,

research and design of media literacy education for

youth, educators and parents. The Consortium

focuses on K-12 grade youth and their parents and

communities. The research efforts include nutrition

and health education, body image/sexuality, safety

and responsibility in media by consumers and

www.consortiumformedialiteracy.org creators of products.

The Consortium is building a body of research,

interventions and communication that demonstrate

scientifically that media literacy is an effective

intervention strategy in addressing critical issues

for youth.

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 6

Resources for Media Literacy

Study on Media Literacy in Country X

CML recently received this report which expresses, from a policy perspective, the current state

of media literacy education in a different country. Our observation is that this report while an

important undertaking in its own context reflects the state of media literacy education in

MANY places. This report is set in a European country, we have put in blanks to see if our

idea about interchangeability holds true. What do you think?

On 8th September, the United Nations' International Literacy Day, a study on media literacy will

be presented in a major city in our country. Media literacy is becoming an increasingly

important topic in our region of Europe, and this is the first publication dealing with media

literacy here.

The publication provides insight into the modern concept of media literacy, analyzes

environmental factors that influence its development in [country X], and identifies actors who,

with proposed measures, can help improve the media literacy skills of its citizens.

The author starts with the presumption that media literacy competency of individuals is greatly

affected by surrounding environmental factors, such as media education, how media literacy is

represented in media policy, how the media industry and civil society promote media literacy,

and accessibility to media. This study suggests that the environment in [country X] provides

some stimuli for the development of media literacy, but also dampens its development,

especially in the fields of media education and media accessibility. Media literacy is not given

adequate attention, neither in public nor in media education or media policy. The concept of

media literacy itself is interpreted differently here, even among media professionals and NGO

activists who actively promote it. Academic articles and publications on the subject are rare,

and comprehensive research on media literacy does not exist.

Media education as education about media can be found as Media Culture in elementary and

secondary educational curricula, under the subjects of native language and literature in

primary schools, and democracy and human rights in secondary schools. However, the overall

presence of media education in our educational system is unsatisfactory in both quality and

quantity. This study shows that media education in [country X] focuses on traditional media

and does not reflect the development of new media and ICTs. Training in media education is

not mandatory for teachers, and teaching tools for media education/literacy are either

unavailable or unknown to teachers. Media education is not a priority, nor is it given sufficient

attention in education strategies. Given its importance for the development of media literacy,

this study suggests that media education needs to be thoroughly adjusted to the modern

needs of both students and teachers in [country X].

Analysis of media policy as a factor which influences media literacy shows that currently media

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 7

literacy is explicitly mentioned in only one legal document, the Broadcast Sector Policy, and it

is not set as a strategic objective in the field of information, media and communications.

Nevertheless, within our laws and subordinate regulations, a solid foundation for media literacy

development has been already laid, primarily through the establishment of a modern

regulatory authority - Communications Regulatory Agency (CRA) - as well as through a

modern regulatory framework harmonized with European standards. The CRA is continuously

active in media literacy development and collaborates with other actors in the field. The Press

Council in [country X], a self-regulatory body for print and online media, has also contributed to

a positive environment for the development of media literacy. However, in order to achieve

long-lasting results and to be able to assess media literacy levels of [country X ] citizens,

media literacy needs to play a more substantial role in media policy. Competencies of all the

actors, including the ministries, regulators, public broadcast service, etc., need to be clearly

defined.

Analysis of media industry activities as factors that influence media literacy development in

[country X] shows that the environment provides some incentives for development, primarily

through the activities of the Press Council, as well as through a very active film industry that

offers different educational programs within numerous film festivals. Traditional media outlets

such as daily newspapers, TV and radio tend not to undertake activities that would help

transform their audiences into competent media consumers. It is also evident that

telecommunication companies and Internet service providers do not invest enough effort to

introduce their clients to new technologies and the possible risks associated with them.

This study identifies ten NGOs in [country X] as key players in media literacy development.

These organizations have offered educational seminars and workshops, established web

portals, organized conferences, and conducted campaigns. The focus of their activities has

been on the development of citizens abilities to critically analyze and evaluate media content.

The activities are aimed towards different age groups, although senior citizens are completely

excluded from this process. It has also been acknowledged that better collaboration and better

coordination of activities among different NGOs is necessary in order to integrate all aspects of

media literacy and to include all target groups. The weakest point of these activities, as

identified in the analysis, is the financial aspect, as there is a lack of public funds to support

such activities.

Media accessibility is also a factor in the development of media literacy. In comparing the

accessibility of TV, radio, print, cinema, mobile phones and Internet in [country X] and

elsewhere in Europe, statistical data shows that [country X] is significantly behind the

European average. The exception is accessibility of TV, which is 99% of the EU average.

Accessibility of radio and mobile phones in [country X] is over 60% of the European average,

which is satisfactory. A significant deficit is shown in daily print and internet access, which is

slightly over 40% of the European average. Access to cinema is the lowest of all of these, just

17% of the European average.

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 8

In its last chapter, this publication tries to answer the question How to improve media literacy

in [country X]? In European practice, improvement of media literacy is considered an

obligation of the state, as well as that of other actors, such as the media industry and NGOs. A

better environment also lends itself to better individual competencies in media literacy. Bearing

in mind the European concept of media literacy and the state of its development in [country X],

this study suggests 20 concrete measures to enhance media literacy of [country X] citizens.

These include promoting discussion among all relevant actors on the status and development

of media literacy; qualitative and quantitative integration of media education into curricula;

development of teaching tools for media literacy; and securing financial support for increasing

media literacy activities.

Publication of Media Literacy in [country X] was printed with the support of Internews [country

X] and represents a part of Internews efforts to contribute to the enhancement of media

literacy in [country X].

COUNTRY X = Bosnia and Herzegovina, abbreviated as BH or BiH.

AUTHOR: Lea Tajic, Communications Regulatory Agency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Head

of International Cooperation in Broadcasting.

CMLs thanks go to Lea for sharing this report and for inadvertently reporting on the state of

media literacy education throughout most of the world. For those who have contrary

information, please let us know!

Sources Cited in this Issue

Ravitch, Sharon M., and Riggan, Matthew. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks

Guide Research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2012.

Shields, Patricia M., and Tajalli, Hassan. Intermediate Theory: The Missing Link in

Successful Student Scholarship. Journal of Public Affairs Education 12.3 (2006):

313-334.

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 9

Med!aLit Moments

Why Dont I See What You See?

Today, online advertisements are tailor-made for individual recipients, but it can be difficult to

discern that fact unless someone else shows you the ads that have been targeted to them. In

this MediaLit Moment, your middle school students will have the opportunity to lift the veil on

the customization of media content by examining domestic and international covers for the

same magazine. In the process, theyll imaginatively take the position of media producers as

they attempt to track the inferences producers made about different audiences.

Ask students to offer possible reasons why producers would print different covers for domestic

and international editions of the same magazine.

AHA!: Everybody in the U.S. sees the same cover for Time magazine, but somebody in

Europe or Asia might see something totally different!

Key Question #3: How might different people understand this message differently?

Core Concept #3: Different people experience the same media message differently.

Key Question #3 for Construction: Is my message engaging and compelling for my target

audience?

Grade Level: 6-8

Materials: computer with high speed internet access, LCD projector and screen; or print outs

of selected website pages

An internet search for Time magazine cover will bring you to a page on the Time website

which (usually) displays covers for all four regions in which the magazine is distributed.

Occasionally you will need to do some additional searching to view international covers. The

page should also allow you to search for past covers by date. Here are some dates for issues

of Time whose domestic and international covers differ significantly: July 1st, 2013 (v.182, n.

1), December 5th, 2011 (v. 178, n. 22), October 3rd, 2011 (v. 178, n. 13), November 29th, 2010

(v. 176, n. 22).

Activity: Have fun talking up the fact that media usually seem to be made the same way for

everyonebut not always. Discuss examples aside from magazine covers, if you can find

any. Next, display or pass out a printout of one of the Time magazine covers. You may need

to briefly explain the social or political context for international covers. Why would Time

magazine print different covers in the U.S. and abroad? Introduce Key Question/Core

Concept #3. How do these domestic and international covers differ? Why would the

producers create these particular covers for these audiences? Ask them to take the point of

view of the producers, and introduce them to Key Question #3 for Producers: Is my message

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 10

engaging and compelling for my target audience?

The Five Core Concepts and Five Key Questions of media literacy were developed as part of the Center

for Media Literacys MediaLit Kit and Questions/TIPS (Q/TIPS) framework. Used with permission,

2002-2013, Center for Media Literacy, http://www.medialit.com

CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments August 2013 11

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Orientation Guide - 12 Week YearDocument4 paginiOrientation Guide - 12 Week YearSachin Manjalekar89% (9)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- RME Closed Door Part 2 - TechnicalDocument6 paginiRME Closed Door Part 2 - TechnicalMackeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Pdfcoffee - Com b000051 NHWP Preint TB Ksupdf PDF FreeDocument168 paginiOpen Pdfcoffee - Com b000051 NHWP Preint TB Ksupdf PDF FreeMHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Problem Management Process Ver1.0Document32 paginiProblem Management Process Ver1.0drustagi100% (1)

- Conducting A Nurse Consultation: ClinicalDocument6 paginiConducting A Nurse Consultation: ClinicalAlif Akbar HasyimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Or Ch5 Queing ZaferDocument12 paginiOr Ch5 Queing ZaferMackeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Time and Motion Studies - Management - Oxford BibliographiesDocument27 paginiTime and Motion Studies - Management - Oxford BibliographiesMackeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Water Crisis?: For A PopulationDocument6 paginiWhat Is Water Crisis?: For A PopulationMackeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3-12-19 Formulating Meaningful ExpressionsDocument2 pagini3-12-19 Formulating Meaningful ExpressionsMarianne Florendo GamillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applicationform Draft Print For AllDocument3 paginiApplicationform Draft Print For AllShankha Suvra Mondal ChatterjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Single Sex EducationDocument7 paginiSingle Sex EducationBreAnna SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colegio de Calumpit Inc.: Iba O' Este, Calumpit, BulacanDocument1 paginăColegio de Calumpit Inc.: Iba O' Este, Calumpit, BulacanJessie AndreiÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLP Multimedia ElementsDocument11 paginiDLP Multimedia ElementsThyne Romano AgustinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anurag Goel: Principal, Business Consulting and Advisory at SAP (Among Top 0.2% Global SAP Employees)Document5 paginiAnurag Goel: Principal, Business Consulting and Advisory at SAP (Among Top 0.2% Global SAP Employees)tribendu7275Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit 5 Mock Paper1Document78 paginiUnit 5 Mock Paper1SahanNivanthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Epistles of St. Paul Written After He Became A Prisoner Boise, James Robinson, 1815-1895Document274 paginiThe Epistles of St. Paul Written After He Became A Prisoner Boise, James Robinson, 1815-1895David BaileyÎncă nu există evaluări

- ATG - NovicioDocument4 paginiATG - Noviciorichie cuizon100% (1)

- TheoriesDocument14 paginiTheoriesChristine Joy DelaCruz CorpuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Purposive Communications 2 Notes 6Document5 paginiPurposive Communications 2 Notes 6Gilyn NaputoÎncă nu există evaluări

- FDA-2011 Gen. Knowledge Key AnsDocument8 paginiFDA-2011 Gen. Knowledge Key AnsyathisharsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class Will and Testament ExampleDocument2 paginiClass Will and Testament ExampleQueenie TenederoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Geography 12 C.P. Allen High School Global Geography 12 Independent Study SeminarsDocument2 paginiGlobal Geography 12 C.P. Allen High School Global Geography 12 Independent Study Seminarsapi-240746852Încă nu există evaluări

- School Culture and Its Relationship With Teacher LeadershipDocument15 paginiSchool Culture and Its Relationship With Teacher LeadershipCarmela BorjayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pulpitis ReversiibleDocument7 paginiPulpitis ReversiibleAlsilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roya Abdoly ReferenceDocument1 paginăRoya Abdoly Referenceapi-412016589Încă nu există evaluări

- Grade 8 Music 3rd QuarterDocument38 paginiGrade 8 Music 3rd Quarternorthernsamar.jbbinamera01Încă nu există evaluări

- Monthly Meeting English - Filipino Club: TH RDDocument3 paginiMonthly Meeting English - Filipino Club: TH RDMerben AlmioÎncă nu există evaluări

- List OpenedSchoolDocument17 paginiList OpenedSchoolRamesh vlogsÎncă nu există evaluări

- RGB Line FollowerDocument5 paginiRGB Line FollowerTbotics EducationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question Aware Vision Transformer For Multimodal ReasoningDocument15 paginiQuestion Aware Vision Transformer For Multimodal ReasoningOnlyBy MyselfÎncă nu există evaluări

- MISDocument11 paginiMISdivyansh singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gcse Esl Listening Question Paper Nov 19Document16 paginiGcse Esl Listening Question Paper Nov 19mazen tamerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20 Points RubricsDocument1 pagină20 Points RubricsJerome Formalejo,Încă nu există evaluări

- Iss Clark Kozma DebateDocument8 paginiIss Clark Kozma Debateapi-357361009100% (1)