Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Sellars 1969

Încărcat de

Mian Umair NaqshDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Sellars 1969

Încărcat de

Mian Umair NaqshDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

International Phenomenological Society

Basic Issues of Philosophy. Experience, Reality, and Human Values by Marvin Farber

Review by: Roy Wood Sellars

Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Jun., 1969), pp. 602-604

Published by: International Phenomenological Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2105544 .

Accessed: 14/01/2015 00:00

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

International Phenomenological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Philosophy and Phenomenological Research.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 14 Jan 2015 00:00:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS

Basic Issues of Philosophy. Experience, Reality, and Human Values.

MARVINFARBER. New York: Harperand Row, 1968. Pp. 290.

This book is a systematicpresentationof Professor Farber's philo-

sophical outlook. And, in so doing, it covers a wide range of topics,

alreadyhinted at in his supplementarytitle. I enumeratea few of them.

There is the discussion of The Nature and Function of Philosophy,

Philosophy and the Methods of Inquiry, Experience and the Problems

of Philosophy,Monism and Pluralism,Approachesto a Philosophy of

Values, Problemsof the Philosophyof Religion.

Professor Farber is a systematic thinker who, while a specialist in

Husserl's phenomenology,has kept his eye on movements in French,

British and Americanphilosophy.Nor is this all. He has been a student

of Marxisttheory as well. The result is that he has a wide perspective.

This is clearly evident in the way he seeks to do justice to Husserl's

methodogenic attempt at establishing "a clean slate out of items of

experience."This, one knows, involves the method of bracketingcom-

monsenseand scientificbeliefs. This distinctivemethodis contrastedwith

the logico-semanticalmethodsof currentAnglo-Americanphilosophyand

the dialecticalmethod of Marxism.

I could not help reflectingon this summaryof methodsand wondering

how my own approachcould be best formulated.As I looked back on it,

it consistedlargelyof concentrationon perennialproblemsand tryingto

get clues which would help to solve them. And I have been led to enter-

tain the suspicionthat stress on methods was, in some measure, an in-

dication of failures. I have great respect for Husserl's acumen but did

he not end as an idealist?Farber,on the other hand, is, like me, a realist

and a materialist.It has been suggestedto me that phenomenologyhas

something in common with linguistic analysis. Both are analytic and

reflectivebut with no clear leads to reality. As Farber later shows, an

able and somewhatdevious man like Scheler was able to play fast and

loose in the field.

Chapterthree is an interestingone and summarizesvery well facts

aboutperceivingand traditionalattitudes.It was a hard nut to crack and

602

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 14 Jan 2015 00:00:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS 603

problemsgalorearose, such as the problemof universalsand the problem

of permanenceand change.As Farberpoints out, both Plato and Hegel

turned away from perceivingto abstractthought. Locke got shelved in

ideas as the primary objects of knowledge, just as Russell later got

enmeshedin knowledgeof acquaintance.There is good materialin this

chapterfor a competentteacher. It has always amusedme that Dewey,

insteadof facing up to the difficultiesinherentin the level of perceptual

knowing,turnedaside to castigatethe social attitudeshe found at work.

Radicalismfavoredthe stresson sensations,while conservatismsupported

the reason. Surely, all too simple a dichotomy. Was not eighteenth-

centuryrationalismratherradical?This externalapproachappearsagain

in the Bentley-Deweyresort to "transactions"as a cure-all.But I must

hurryon.

In ChapterFive, Farberconcentrateson knowledgeand judgmentand

their categories.The problemof the "Given"is explored,as well as that

of "Certainty."This chaptershows wide reading and awarenessof cur-

rent discussions.For instance,C. I. Lewis'shandlingof "contrary-to-fact

statements"is explored.Surely,the emphasishere is upon laws. Were I

to throw a penny down, it would fall. The question of the relation of

judgmentto reality is broached.What I like about the book is its com-

prehensiveness.The readeris not asked to choose betweencontemporary

fashions.I remembera book by a Princetonprofessorwho just assumed

that one had to be either a logical positivist,a pragmatist,or a linguistic

analyst.There was no fourth. This is what I call journalisticphilosophy.

ProfessorFarberbelongs to an older and soundertradition.

And now we come to ontology. Here the author deals with the old

opposition between monism and pluralismof which Royce and James

made so much. Royce, it will be recalled, founded his system on a

primaryknower. James, on the other hand, stuck to a variety of expe-

riencerswith truthsomethingincompletebetweenthem. Farbergoes back

to Parmenidesand his changelessOne. But he also glances at the ques-

tion of internaland externalrelations.Whiteheadand events come into

the picture.Farberseems to take a mediatingview here. Unity and parts

are both required.I am not quite certain of the role played by Carnap

and Sheffer. He distinguishesbetween formal unity, which is a sort of

ideal, and existentialunitywhich science explores.His remarkson White-

head's method of extensive abstractioninterested me. I have myself

tended to build on Einstein'scontrastbetween pure and applied mathe-

matics. I quite agree with Farber that real instants must be protensive.

One cannotget time out of the timeless.But may I be allowed to inter-

ject that I regardWhitehead'sepistemologyas a mess.

In chapterSeven, our authorexploresexistencefarther.He raises the

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 14 Jan 2015 00:00:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

604 PHYLOSOPHY RESEARCH

ANDPHENOMENOLOGICAL

questionof the meaningof existence.Here his wide readingis apparent.

McTaggartand Hoernle are given their say, as they should be. The

questionof essence is raised. As I see it, the questionof existence stands

out in such queriesas Russell's, "Do lions exist?"If we answeraffirma-

tively, we are giving status to a claim. But the realm of existence is

presupposed.Farber'srealism begins to stand out in his aside on "The

destructionof the world in phenomenology."He has always insistedthat

the bracketingwas an affair of method.

And now we have his commentson Germanexistentialismand philo-

sophical anthropology.He is not impressedby it. In a previous book,

Naturalismand Subjectivism,which I had the honor of reviewing, he

brought out his aversion to much of recent German philosophy to

empiricismand naturalism.Nationaltraditionshere play theirpart. I have

always admiredhis wide acquaintancewith Germanphilosophicallitera-

ture. I fear I have been ratherimpatient.But Farberhas been scholarly

in this domain.

We come now to the human scene with value, ethics, and religion.He

raises the question of objectivity in ethics. Here his stress is on the

satisfactionof humanneeds and interest.I sense the influenceof Ralph

Barton Perry. I would, in a measure, agree but would emphasizethe

objective import of value ascriptionsor appraisals.These differ from

cognitionsand yet are objectivelyreferentialand concernthe role of the

object in the human economy.

In the final chapter,Ten, the Marxist ingredientin Farber'soutlook

comes to the front. As is well known, Feuerbachplayed a guidingrole.

The idea of God is a projection.Farberrightlygoes back to that pioneer,

Xenophanes. And he also pays attentionto the mystics in the Middle

Ages, such as Meister Ecklhart. He also agrees with most scholars that

the traditionalproofs of God's existencehave logical weakness.Thus he

comes out along the lines of humanism.

As I said in the beginning,this is philosophy in the grand manner

without apologies. It is solid and comprehensiveand has no particular

nostrum.These are its virtues. It may not be journalisticand with an

eye on the latest fashionand sloganbut it is well-groundedand scholarly.

ROY WOOD SELLARS.

OF MICHIGAN.

UNIVERSITY

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 14 Jan 2015 00:00:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Gaulish DictionaryDocument4 paginiGaulish DictionarywoodwyseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muhammadumair Muhammad Umair: ExpertiseDocument2 paginiMuhammadumair Muhammad Umair: ExpertiseMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research List 2012Document4 paginiResearch List 2012Mian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plato's Philosophy of RealityDocument2 paginiPlato's Philosophy of RealityMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interaction of Libraries and Publishers: Manfred KochentDocument9 paginiInteraction of Libraries and Publishers: Manfred KochentMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- INFORMS Title List 2012Document1 paginăINFORMS Title List 2012Mian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012 CSP NRC Title ListDocument1 pagină2012 CSP NRC Title ListMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012 IET Title ListDocument1 pagină2012 IET Title ListMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aviation MuseumDocument2 paginiAviation MuseumMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Space For ChildrenDocument5 paginiLearning Space For ChildrenMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duke Title List 2011Document2 paginiDuke Title List 2011Mian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research PaperDocument29 paginiResearch PaperMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public Library SynopsisDocument5 paginiPublic Library SynopsisMian Umair Naqsh0% (2)

- Psychology: University of GujratDocument31 paginiPsychology: University of GujratMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Methodolo GY Salman Diyyal 1202479 5-005: Submmited To: Sir Abdul RehmanDocument7 paginiResearch Methodolo GY Salman Diyyal 1202479 5-005: Submmited To: Sir Abdul RehmanMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEPACDocument3 paginiPEPACMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Submitted To: Ma'M Fakhira Gul Submitted By: Mian Umair ROLL NO: 12014795-023 Semester: 8 Department: ArchitectureDocument3 paginiSubmitted To: Ma'M Fakhira Gul Submitted By: Mian Umair ROLL NO: 12014795-023 Semester: 8 Department: ArchitectureMian Umair NaqshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deeg Palace Write-UpDocument7 paginiDeeg Palace Write-UpMuhammed Sayyaf AcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winifred Breines The Trouble Between Us An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in The Feminist MovementDocument279 paginiWinifred Breines The Trouble Between Us An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in The Feminist MovementOlgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RH Control - SeracloneDocument2 paginiRH Control - Seraclonewendys rodriguez, de los santosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exposicion Verbos y AdverbiosDocument37 paginiExposicion Verbos y AdverbiosmonicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prinsip TriageDocument24 paginiPrinsip TriagePratama AfandyÎncă nu există evaluări

- TreeAgePro 2013 ManualDocument588 paginiTreeAgePro 2013 ManualChristian CifuentesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan 2 Revised - Morgan LegrandDocument19 paginiLesson Plan 2 Revised - Morgan Legrandapi-540805523Încă nu există evaluări

- LabDocument11 paginiLableonora KrasniqiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mount Athos Plan - Healthy Living (PT 2)Document8 paginiMount Athos Plan - Healthy Living (PT 2)Matvat0100% (2)

- The Impact of Video Gaming To The Academic Performance of The Psychology Students in San Beda UniversityDocument5 paginiThe Impact of Video Gaming To The Academic Performance of The Psychology Students in San Beda UniversityMarky Laury GameplaysÎncă nu există evaluări

- LDS Conference Report 1930 Semi AnnualDocument148 paginiLDS Conference Report 1930 Semi AnnualrjjburrowsÎncă nu există evaluări

- PDF Document 2Document12 paginiPDF Document 2Nhey VergaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of AIDocument27 paginiHistory of AImuzammalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Magical Number SevenDocument3 paginiThe Magical Number SevenfazlayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Fiction FilmsDocument5 paginiScience Fiction Filmsapi-483055750Încă nu există evaluări

- An Improved Version of The Skin Chapter of Kent RepertoryDocument6 paginiAn Improved Version of The Skin Chapter of Kent RepertoryHomoeopathic PulseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Read Online 9789351199311 Big Data Black Book Covers Hadoop 2 Mapreduce Hi PDFDocument2 paginiRead Online 9789351199311 Big Data Black Book Covers Hadoop 2 Mapreduce Hi PDFSonali Kadam100% (1)

- Mehta 2021Document4 paginiMehta 2021VatokicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bibliography of Loyalist Source MaterialDocument205 paginiBibliography of Loyalist Source MaterialNancyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fabre, Intro To Unfinished Quest of Richard WrightDocument9 paginiFabre, Intro To Unfinished Quest of Richard Wrightfive4booksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shostakovich: Symphony No. 13Document16 paginiShostakovich: Symphony No. 13Bol DigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Laguage Teaching - Nzjournal - 15.1wiechertDocument4 paginiForeign Laguage Teaching - Nzjournal - 15.1wiechertNicole MichelÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 History of Grammatical StudyDocument9 pagini01 History of Grammatical StudyRomanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complexity. Written Language Is Relatively More Complex Than Spoken Language. ..Document3 paginiComplexity. Written Language Is Relatively More Complex Than Spoken Language. ..Toddler Channel TVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Pregnancy and Its Effect On The Mental Health of Students in Victoria Laguna"Document14 paginiEarly Pregnancy and Its Effect On The Mental Health of Students in Victoria Laguna"Gina HerraduraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippines My Beloved (Rough Translation by Lara)Document4 paginiPhilippines My Beloved (Rough Translation by Lara)ARLENE FERNANDEZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Afghanistan Law Bibliography 3rd EdDocument28 paginiAfghanistan Law Bibliography 3rd EdTim MathewsÎncă nu există evaluări

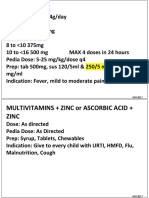

- Common RHU DrugsDocument56 paginiCommon RHU DrugsAlna Shelah IbañezÎncă nu există evaluări