Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Colonel Albert: Civil War First, Then Shoe Business

Încărcat de

Vincent MutambirwaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Colonel Albert: Civil War First, Then Shoe Business

Încărcat de

Vincent MutambirwaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Pope

COLONEL ALBERT

Colonel Albert Pope. (Photo courtesy of

University of California)

Stop and think about downtown Boston or any other major city. What do you

see? No doubt your answer would include sidewalks crowded with people, busy

streets, and lots of traffic. Now, try to imagine a time when horse-drawn carriages

rolled down city streets, and a network of paved roads did not exist. This was the

world of Colonel Albert A. Pope — at one time, the world’s largest producer of

bicycles and a pioneer in the manufacture of automobiles.

Albert Pope, industrialist, businessman, and philanthropist, was born in Boston, This summary draws heavily on

Massachusetts, in 1843. He was the fourth child in a large family. His father, three sources: Bruce Epperson,

“The American Bicycle Industry

Charles Pope, earned and lost a fortune in real estate speculation in the 1850s; 1868-1900”; Stephen B. Goddard,

and his financial struggles made a lasting impression on Albert.1 At age nine, Colonel Albert Pope and His

realizing the family financial situation, Albert began working at a nearby farm after American Dream Machines; and

Glen Norcliffe, “Popeism and

school. By 16, he was working full-time, first in Boston’s markets and later as a Fordism: Examining the Roots

store clerk.2 of Mass Production.”

Civil War First, Then Shoe Business

In 1862, at age 19, Pope entered the Union army as a second lieutenant in the

35th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. Pope fought at such key battles as

Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Vicksburg. He saw many troops suffer from hunger,

wounds, diseases, and poor sanitation. Years later, in 1898, Pope had a monu-

ment erected at Antietam Creek to memorialize those in the 35th who had died

in that battle.3

Colonel Albert Pope 1

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

Towards the end of the war, Pope was

rewarded for his distinguished service in

battle with the honorary rank of lieutenant

colonel. Pope used the title “Colonel” for the

rest of his life. Pope’s cousin and later busi-

ness associate, George Pope, also served in

the Civil War, becoming a lieutenant colonel

in the 54th Massachusetts, a regiment of

black enlisted men.

Pope had saved $900 from his Civil War

earnings. He decided to invest this money

in making decorations, supplies, and tools

for the shoe industry, one of the largest

employers in Massachusetts at that time.

His investment paid off. After one year, his

initial $900 had increased tenfold.4 Pope

went on to build a successful business in

shoe decorations and supplies. His success

enabled him to contribute to the support

of his family and to send his younger twin

sisters to medical school.

In 1871, Pope married. His wife, Abby, was a

believer in women’s rights, a member of the

Women’s Industrial Union, and a supporter

of the Boston Symphony. Albert and Abby

seem to have had a rich and full life. They Reproduction of Pope Manufacturing poster from the collection of Zip and

Carol Zamarchi.

had six children, one of whom died in

infancy. In later years, friends and family were entertained at their Boston home

on Commonwealth Avenue and at their 50-acre seaside estate in Cohasset.

Pope Is Drawn to Bicycles

In 1876, as a member of the City Council of Newton, Pope attended the

Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Here, he saw a high front-wheeler bicycle

from Britain. Although the artist Winslow Homer had introduced Americans to

the bicycle in 1869, Pope found himself fascinated by this “. . . outlandish steel

skeleton with its front wheel nearly as tall as the man . . .”5

Colonel Albert Pope 2

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

Sometime in 1877, Englishman John Harrington visited Albert Pope. Pope

requested his assistance in developing an experimental model of the high-

wheeler.6 Pope was so thrilled with Harrington‘s model that he immediately Pope actively promoted

ordered eight Duplex Excelsiors from an English factory. Pope was not satisfied the use of bicycles. He

with being an importer of bicycles, however. He wanted to manufacture the high- pushed aggressively to

wheeler in America himself. But to do this, he needed to obtain a key patent. improve the conditions

in which people could

Pope Acquires Bicycle Patent ride their bicycles and

Pierre Lallement, a French mechanic, developed the original model of the to forestall restrictions

velocipede, the precursor of the high-wheel bicycle, in Paris in 1863. Lallement on the use of bicycles.

subsequently moved to Connecticut, where he completed work on an improved

version. By the spring of 1866, he had formed a partnership with James Caroll,

an American businessman who lent him the money he needed to file for a

patent. Lallemont received the patent that fall, but he was unsuccessful in selling

velocipedes and returned to France in 1868. The patent was purchased by Calvin

Witty, a carriage maker who also produced velocipedes. The high royalty fee that

Witty charged other producers is thought to have helped stifle the growth of the

industry in the United States.

In the mid 1870s, the patent changed hands again. Half of the patent rights

were acquired by Richardson and McKee Company of Boston and the other half,

by a Vermont carriage maker, although Richardson and McKee managed the

entire patent.7 Pope had a license from Richardson and McKee, but he found the

royalty fee burdensome. He offered Richardson and McKee a substantial sum for

half of their interest. With this one-quarter share in the patent, Pope quickly took

a train to Vermont and bought the half interest of the Montpelier Manufacturing

Company—just before a letter from Richardson and McKee arrived also offering

to buy their half interest.8

Throughout his life, Pope recognized the importance and usefulness of patents.

He used patents to protect his own innovations from imitators, and he purchased

others’ patents in order to gain access to their technologies without fear of being

sued or charged costly royalties. Patent licenses were themselves a source of

revenues. Patents were also a tool for limiting competition and propping up

prices. An example of this can be seen in Pope’s litigation against the Overman

Wheel Company. During the 1880s, Overman came out with first a tricycle and

then a bicycle that were of high quality and lower cost than Pope’s products.

Pope responding by suing Overman, claiming violation of various Pope patents.

Litigation continued for several years at considerable expense to both firms.9

Eventually, an agreement was reached. The “treaty of Springfield” called for Pope

Colonel Albert Pope 3

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

and Overman to cross-license each other’s patents and made Pope responsible

for enforcing Overman’s patents as well as his own.10

Pope Makes His Bicycle in Manufacturing Mecca

To manufacture his bicycle, Pope turned to the Weed Sewing Machine Company

of Hartford, Connecticut. Hartford and neighboring Springfield were on the fore-

front of metal manufacturing technology at the time. The Springfield Armory, a

major weapons facility of the U.S. government, had actively promoted the use

of highly specialized machines to make changeable parts for firearms. Machine-

made parts were more uniform than hand-made; a broken gun, for example,

could easily be fixed with a replacement part. Machine production also allowed

for large production runs and lower costs. The Armory encouraged firearms

makers to share their advances, with the result that the new production tech-

niques spread to neighboring facilities and were adopted for a host of complex

metal products.

The Weed Sewing Machine Company was well known for its use of inter-

changeable parts and for its high-quality machinists. It was already a contract

manufacturer making components and machines for others.11 In 1878, Pope

contracted with Weed to produce 50 high-wheelers, now called by the brand

name Columbia.12

Pope priced the new Columbia at $95, undercutting the imported Duplex

Excelsior, which was priced at $112.50.13 The Columbia sold well, and Pope

ordered more. Over time, the Weed Sewing Machine Company produced more

and more bicycles and fewer sewing machines. In 1881, Pope purchased control

a minority share of the Weed Sewing Machine Company. He acquired complete

ownership about ten years later.

Better Roads, No Bike Bans

Pope actively promoted the use of bicycles. He pushed aggressively to improve

the conditions in which people could ride their bicycles and to forestall restrictions

on the use of bicycles. American roadways in the 1880s were much different

from the roads of today. They were unpaved and often filled with potholes, loose

stones, and mud. Horses were everywhere. Add to this mix a high front-wheeler

with a cyclist perched precariously atop. Men and women feared being run over.

Horses spooked when the bicycle went by, and dogs chased it. Public officials

responded with proposals to ban the bicycle from public parks and streets.

Colonel Albert Pope 4

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

Pope came to the bicycle’s defense. He chal-

lenged restrictive ordinances and formed bicycle

clubs that would create a positive image of bicycles

and cyclists. Although the elite initially dominated

membership, as they were the only individuals who

could comfortably afford bicycles, the clubs pressed

for legislation to improve roadways, fought tolls on

bicycles, and generally defended the freedom of

American roads.

Pope also encouraged building better roads.

He financed courses to train road engineers at

MIT, and he persuaded the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts to set up a highway commission

for the improvement of roads. He sponsored the

publication of Good Roads,14 a magazine that

provided information and lobbied state legislatures

and Congress for better roads. Over time Pope’s

efforts paid off. By 1890, several states and the

federal government had created experimental

road-building programs.

Safer, Lighter Bicycles

The high-wheel bicycle presented other problems

that limited its popularity. Women and children

complained that, at 70 pounds, the bicycle was too

heavy. Smaller cyclists also complained about the

difficulty of pushing the pedals hard enough to turn

Reproduction of Pope Manufacturing poster from the collection of Zip and Carol

the big wheel fast enough and gain momentum. Zamarchi.

During the 1880s and early 1890s, a number of innovations made the bicycle

easier to use and greatly expanded the market. Of particular importance was the

development of the “safety bicycle,” so called because it was safer than the high

wheelers it displaced. The safety bicycle had equal-sized wheels. Power came

from the rear wheel, which was connected to the pedals by a chain. The first

fully successful safety, the Rover, was developed in England in 1885-86. Pope

produced his first safety in 1888.

Colonel Albert Pope 5

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

The use of hollow, durable-steel tubes for the bicycle frame made it possible to

substantially reduce the weight of the bicycle. Pneumatic tires, inflated tires filled

with compressed air, absorbed road vibrations.

Such changes made the bicycle more attractive, especially to women. Women’s

clothes in the late 19th century were at odds with cycling. Long skirts and volu-

minous petticoats made riding high wheelers impractical. Even the safety bicycle

posed problems, as clothing could catch in the chain. Cyclists began to dress in

less formal clothing such as knickerbockers, knee length stockings, and divided

skirts. Susan B. Anthony remarked that “the bicycle has done more for the eman-

cipation of women than anything else in the world,” encouraging women to

exchange their cumbersome and confining clothes in favor of “common sense

dressing.”15

Boom and Bust in Bicycles

With the introduction of the safety bicycle demand grew rapidly, and Pope and

other bicycle manufacturers invested heavily in additional production capacity.

Pope bought all of Weed and placed it under his control. Pope Manufacturing

expanded substantially and sought to control all aspects of bicycle produc-

tion. Pope bought the company that supplied his bicycle tires. He also set up a

company to produce hollow steel tubing. By buying up his suppliers, Pope could

ensure a reliable supply of materials and components and control quality.

For a time, business was good, for both Pope and his competitors. Columbia

bicycles were sold in every major market of the world, and Pope was a household

name. More and more firms entered the market, with entry made easier by firms

that specialized in producing bicycle parts and specialized bicycle machinery.

The good times did not last. By 1897, the bicycle market was saturated. Bicycle

prices fell sharply, and many firms went bankrupt, including Pope’s rival, Overman.

Over the next two years, A.G. Spalding, the founder of a chain of sporting goods

stores and factories, led an effort to consolidate the industry. It was hoped that

reduced competition would restore profitability. Pope’s bicycle operations and a

number of others were combined to form the American Bicycle Manufacturing

Co. (ABC). By 1902, however, ABC itself had failed and was in receivership.

Pope Produces Automobiles

At the same time that the bicycle industry was falling on hard times, the automo-

bile era was beginning. Many innovations that were used in the bicycle industry,

such as pneumatic tires, wire wheels, ball and roller bearings, differential axles,

Colonel Albert Pope 6

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

and spring suspension had direct applicability to the early automobile. Pope

himself had established an automotive division at his Hartford facilities in 1895.

A key issue for Pope and many others was the power source. Would it be steam,

electricity, or gasoline? Pope believed in the future of the electric car. He had seen

an internal combustion car in Paris and deplored the noise and pollution caused

by the automobile. “Who would willingly sit atop an explosion?” he asked.16 The

electric car was cleaner and easier to use. Between 1897 and 1899, Pope’s

operations produced 500 electric cars and 40 gasoline-powered cars. No other

American motor manufacturer at that time was producing as many.17 A British

newspaper writer hailed Hartford as the center of the automobile industry.18

In 1899, Pope was approached by William Whitney, a Wall Street financier and

former Secretary of the Navy, whose brother was Pope’s next-door neighbor at

Cohasset. Whitney intended to place electric taxicabs in major cities throughout

the country, starting with Manhattan. Whitney wanted a company that could

manufacture large numbers of electric vehicles. Pope was then the largest

producer of motor vehicles, primarily electric; and with the bicycle business in a

slump, he had excess capacity. Whitney and Pope combined forces to form the

Columbia and Electric Vehicle Company. Although planning to produce electric

cars, the company also acquired George Selden’s patent for the internal combus-

tion (gasoline) engine.

In 1900, after the Columbia and Electric Vehicle Company had been operating

for only one year, Pope decided to let the Whitney group buy him out. The

Columbia and Electric Vehicle Company was merged into Whitney’s Electric

Vehicle Company. Pope devoted himself to cattle ranching, mining operations,

and other investments in the West and to working for legislation to pave the

roads of America.

In 1903, however, Pope returned to automobile manufacturing. He repurchased

the remains of the Pope Manufacturing Company from its receivers’ committee

in order to produce both cars and bicycles. Most of the cars were now gasoline-

powered, but one plant produced electric vehicles. In addition to Hartford, the

company had plants in Massachusetts, Maryland, Indiana, and Ohio.

Competition in the automobile industry was intense. Henry Ford, in particular, was

successful in producing lower cost vehicles that undercut his rivals. In 1907, Pope

Manufacturing was unable to refinance its debts and was forced into receivership

Colonel Albert Pope 7

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

when it could not pay a debt of $4306.3019 Colonel Pope’s health was failing,

and his son was appointed receiver. Whitney’s Electric Vehicle Company went

into receivership the same year; despite their virtues, electric vehicles were

unable to overcome the inconvenience of requiring frequent recharging of

the battery.

Conclusion

Pope was a pioneer in both the bicycle and the automobile industries. His

contributions are many and varied. He introduced the American public to the

concepts of personal and recreational transportation. He worked ceaselessly for

good roads. He demonstrated the effectiveness of advertising and other mass

marketing approaches. In aggressively reaching out to women, he encouraged

them to free themselves from confining fashions and self-images.

In his manufacturing operations, Pope took key elements of the mass production

process to very high levels. Although the moving assembly line was developed

by Henry Ford, Pope’s plants were distinguished by a very fine division of labor,

a high degree of interchangeability of parts, and extremely precise machining.

He placed very strong emphasis on quality control through inspections. Many

learned from his operations.

Endnotes

1

Glen Norcliffe, “Popeism and Fordism: Examining the Roots of Mass

Production,” Regional Studies, Vol. 31.3, p. 269.

2

Stephen B. Goddard, Colonel Albert Pope and His American Dream

Machines, p. 60.

3

35th Massachusetts Infantry Monument at Antietam National Battlefield,

http://www.nps.gov/anti/monuments/MA_35_Inf.htm.

4

Goddard, p. 60.

5

Goddard, pp. 5–6.

6

Albert A. Pope, unpublished speech, pp. 7–8.

7

Goddard, p. 69.

8

According to Bruce Epperson, although this story is in the Pope Company’s

1907 biography, his own investigations in the patent ledgers at the

National Archives suggest that Pope’s father Charles may have been in

Vermont for as long as a month negotiating with the Montpelier firm

while Pope haggled with Richardson and McKee. The two contracts

were, however, dated only a day apart.

9

Goddard, p. 87.

10

Bruce Epperson, “The American Bicycle Industry, 1868–1900.”

Colonel Albert Pope 8

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

11

Epperson.

12

Goddard, pp. 69–70.

13

Norcliff, p. 269. Goddard cites a price of $90 for the Columbia, p. 76.

14

Goddard, p. 119.

15

Goddard, p. 7.

16

Goddard, p. 13.

17

John Bell Rae, The American Automobile Industry, p. 15.

18

Goddard, p. 136.

19

Goddard, p. 197.

Bibliography

Epperson, Bruce. “The American Bicycle Industry, 1868-1900.” Unpublished

paper, July 2001.

Goddard, Stephen B. Colonel Albert Pope and His American Dream Machines.

North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000.

Norcliffe, Glen. “Popeism and Fordism: Examining the Roots of Mass Production.”

In Regional Studies, Volume 31.3, pp. 267-280.

Pope, Albert A. Unpublished speech. Connecticut Historical Society, 1995. Albert

A. Pope is the great grandson of Colonel Albert A. Pope.

Rae, John Bell. The American Automobile Industry. Boston: Twayne

Publishers, 1984.

Written by Albert Barnor, Economic Education Specialist, and Lynn Elaine

Browne, retired Executive Vice President and Economic Advisor, Federal

Reserve Bank of Boston, September 2003

Colonel Albert Pope 9

Profiles of Economic Decision-makers

www.economicadventure.org

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Black Invention MythsDocument16 paginiBlack Invention MythsjoetylorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Black Invention MythsDocument13 paginiBlack Invention MythsARTofATRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentación Proyecto CUTLURA INGLESADocument13 paginiPresentación Proyecto CUTLURA INGLESAIsidro Robles NavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Look Up, Olympia! A Walking Tour of Olympia, WashingtonDe la EverandLook Up, Olympia! A Walking Tour of Olympia, WashingtonÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Tragic Toast to Christmas -The Infamous Wood Alcohol Deaths of 1919 in Chicopee, MassachusettsDe la EverandA Tragic Toast to Christmas -The Infamous Wood Alcohol Deaths of 1919 in Chicopee, MassachusettsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14-15 Study GuideDocument11 pagini14-15 Study Guideapi-236922848Încă nu există evaluări

- The Industrial Revolution 1750 1900Document40 paginiThe Industrial Revolution 1750 1900Joaquina DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 4 "Carnegie Andrew" to "Casus Belli"De la EverandEncyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 4 "Carnegie Andrew" to "Casus Belli"Încă nu există evaluări

- Look Up, San Francisco! A Walking Tour of Union SquareDe la EverandLook Up, San Francisco! A Walking Tour of Union SquareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Look Up, Batavia! A Walking Tour of Batavia, New YorkDe la EverandLook Up, Batavia! A Walking Tour of Batavia, New YorkÎncă nu există evaluări

- It's All About the Bike: The Pursuit of Happiness on Two WheelsDe la EverandIt's All About the Bike: The Pursuit of Happiness on Two WheelsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (78)

- Chapter 14 Apush Study GuideDocument11 paginiChapter 14 Apush Study Guideapi-240270334Încă nu există evaluări

- New Holand Tractor Tn55 Tn65 Tn70 Tn75 Operators Manual 86584836Document23 paginiNew Holand Tractor Tn55 Tn65 Tn70 Tn75 Operators Manual 86584836kellydecker180191brzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Masonic InventorsDocument12 paginiMasonic InventorsRick DeckardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Say Die: A Kentucky Colt, the Epsom Derby, and the Rise of the Modern Thoroughbred IndustryDe la EverandNever Say Die: A Kentucky Colt, the Epsom Derby, and the Rise of the Modern Thoroughbred IndustryÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Secret History of Brands: The Dark and Twisted Beginnings of the Brand Names We Know and LoveDe la EverandA Secret History of Brands: The Dark and Twisted Beginnings of the Brand Names We Know and LoveEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (10)

- CH 14-15 Study GuideDocument11 paginiCH 14-15 Study Guideapi-235956603Încă nu există evaluări

- Founding Father Benjamin Franklin's Scientific and Political ContributionsDocument5 paginiFounding Father Benjamin Franklin's Scientific and Political ContributionsYourGoddessÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01-14-17 EditionDocument32 pagini01-14-17 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essays On Mankind and Political Arithmetic by Petty, William, Sir, 1623-1687Document66 paginiEssays On Mankind and Political Arithmetic by Petty, William, Sir, 1623-1687Gutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hwsme HistoryDocument11 paginiHwsme Historyapi-347596173Încă nu există evaluări

- Milestones in the Mighty Age of Steam: The Grasshopper and the CorlissDe la EverandMilestones in the Mighty Age of Steam: The Grasshopper and the CorlissÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trailblazing Georgians: The Unsung Men Who Helped Shape the Modern WorldDe la EverandTrailblazing Georgians: The Unsung Men Who Helped Shape the Modern WorldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 14 and 15 KDocument11 paginiChapter 14 and 15 Kapi-236286493Încă nu există evaluări

- Tall Tale America: A Legendary History of our Humorous HeroesDe la EverandTall Tale America: A Legendary History of our Humorous HeroesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Copia de Karl - ProbstDocument3 paginiCopia de Karl - ProbstFrancisco FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading SkillsDocument9 paginiReading Skillshabil muzakiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Midnight Ride Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American EnterpriseDe la EverandMidnight Ride Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American EnterpriseEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- NAME:-Meet H. Sonagara Std:-11 Science ROLL: - 4: Topic: - Inventor and InventionDocument18 paginiNAME:-Meet H. Sonagara Std:-11 Science ROLL: - 4: Topic: - Inventor and Inventionmeet sonagaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cornelius O'Keefe: The Life, Loves, and Legacy of an Okanagan RancherDe la EverandCornelius O'Keefe: The Life, Loves, and Legacy of an Okanagan RancherÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 14and15 2Document11 paginiCH 14and15 2api-236323575Încă nu există evaluări

- Test Bank For Operations and Supply Chain Management 13th Edition JacobsDocument24 paginiTest Bank For Operations and Supply Chain Management 13th Edition Jacobsjamesaustinckpbxydnqf100% (45)

- History ?Document4 paginiHistory ?joshuabaleteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Albert Pike S BackgroundDocument6 paginiAlbert Pike S BackgroundFederico CerianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Metal Life Car: The Inventor, the Impostor, and the Business of LifesavingDe la EverandThe Metal Life Car: The Inventor, the Impostor, and the Business of LifesavingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 14 - Robber BaronsDocument8 paginiLesson 14 - Robber BaronsJohn Michael BanuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 14 and 15 Study GuideDocument14 paginiChapter 14 and 15 Study Guideapi-236296135Încă nu există evaluări

- The Greatest British & American InventorsDocument20 paginiThe Greatest British & American InventorsArmen Neziri50% (2)

- P.O.S.H. Portside Out – Starboard Home My Life StoryDe la EverandP.O.S.H. Portside Out – Starboard Home My Life StoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World of Your Ancestors - Dates - 1800 - 1899: 2 of 6, #2De la EverandThe World of Your Ancestors - Dates - 1800 - 1899: 2 of 6, #2Încă nu există evaluări

- Mbizo 19 Longsecs Longsec1Document1 paginăMbizo 19 Longsecs Longsec1Vincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Bed House PlanDocument1 pagină4 Bed House PlanVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample HD HouseDocument1 paginăSample HD HouseVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- East Elevation 1:100 West Elevation 1:100: WD - 003 ND11FDocument1 paginăEast Elevation 1:100 West Elevation 1:100: WD - 003 ND11FVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

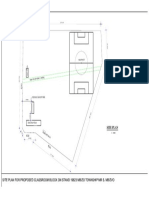

- Mcps Site PlanDocument1 paginăMcps Site PlanVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample House On 300 Sq. MDocument1 paginăSample House On 300 Sq. MVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pad Footings Quantity Take Off: Footing DetailsDocument1 paginăPad Footings Quantity Take Off: Footing DetailsVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Danet 1Document1 paginăDanet 1Vincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A.3site Plan 7385Document1 paginăA.3site Plan 7385Vincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dynamic 20852 ModelDocument1 paginăDynamic 20852 ModelVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petrotrade SurveyDocument1 paginăPetrotrade SurveyVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retaining WallDocument1 paginăRetaining WallVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ZIE Engineering Training Diary GuidelinesDocument4 paginiZIE Engineering Training Diary GuidelinesBright MuzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LECTURE 4 Levelling PDFDocument19 paginiLECTURE 4 Levelling PDFMark Lester Brosas TorreonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doc022 97 90324Document144 paginiDoc022 97 90324Vincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Department OrganogramDocument1 paginăHealth Department OrganogramVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viva Afrika Price List AUGUST 2017 RetailDocument29 paginiViva Afrika Price List AUGUST 2017 RetailVincent Mutambirwa33% (3)

- Arlington AC Guideline WebDocument18 paginiArlington AC Guideline WebVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft House PlanDocument1 paginăDraft House PlanVincent Mutambirwa100% (1)

- Population of Zimbabwe 2012Document178 paginiPopulation of Zimbabwe 2012Vincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estimating TableDocument2 paginiEstimating TableVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Municipality of Kwekwe Stamp: Storeroom 1 Storeroom 3Document1 paginăMunicipality of Kwekwe Stamp: Storeroom 1 Storeroom 3Vincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proposed Medium DensityDocument1 paginăProposed Medium DensityVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Infrastructure Cost ModellingDocument95 paginiWater Infrastructure Cost ModellingVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proposed Residence in A High Density Area in ZimbabweDocument1 paginăProposed Residence in A High Density Area in ZimbabweVincent Mutambirwa100% (1)

- Eureka Projects PVT LTD: Machine Hire Log Sheet Job Site Machine(s) Month Date Work Carried Out Initials OperatorDocument4 paginiEureka Projects PVT LTD: Machine Hire Log Sheet Job Site Machine(s) Month Date Work Carried Out Initials OperatorVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Planning Framework - Local Authority TemplateDocument6 paginiStrategic Planning Framework - Local Authority TemplateVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simple Residential PlanDocument4 paginiSimple Residential PlanVincent MutambirwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ZIE Member Grade ApplicationDocument1 paginăZIE Member Grade ApplicationVincent Mutambirwa0% (1)

- Catalog Ford TDocument228 paginiCatalog Ford TAnonymous hx8lZrÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASTronic Product BrochureDocument8 paginiASTronic Product BrochureRajib BiswasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stringham TeslaDocument33 paginiStringham TeslaSarmad HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sae 17autp06Document45 paginiSae 17autp06FERNANDO JOSE NOVAESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auto ProfessionalsDocument4 paginiAuto Professionalswicka3Încă nu există evaluări

- Honda Case Study Full Mike Jett InterviewDocument8 paginiHonda Case Study Full Mike Jett InterviewSalwa ParachaÎncă nu există evaluări

- APOLLO TYRES SWOT - Internal AnalysisDocument8 paginiAPOLLO TYRES SWOT - Internal Analysisshazia ahmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bolero Car ProjectDocument54 paginiBolero Car ProjectMahesh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- VW Polo Classic 1.4 Technical Specifications and Service AdjustmentsDocument6 paginiVW Polo Classic 1.4 Technical Specifications and Service AdjustmentsAndrej BuberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michigan Driving Automatic Failures List For Driving TestDocument0 paginiMichigan Driving Automatic Failures List For Driving TestSrinivas ChinnamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2ST Seated Leg Curl DiagramDocument10 pagini2ST Seated Leg Curl DiagramJEREMEE MICHAEL TYLERÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statement Regarding Tricycles and New Tricycle Fare MatrixDocument4 paginiStatement Regarding Tricycles and New Tricycle Fare Matrixfagatep100% (2)

- Elecon High Speed Gearbox PDFDocument14 paginiElecon High Speed Gearbox PDFgaurang3005Încă nu există evaluări

- BPW El W BW GW 05 01eDocument38 paginiBPW El W BW GW 05 01ewoulkanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fleet Management ProceduresDocument8 paginiFleet Management ProceduresAnas R. Abu KashefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Partnr.: 027491: Dodané Upevňovací DílyDocument11 paginiPartnr.: 027491: Dodané Upevňovací DílyErik HardiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- LHD Toro0010 (13 Yd3) PDFDocument2 paginiLHD Toro0010 (13 Yd3) PDFDaniel LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- ZF 4WG210Document33 paginiZF 4WG210unstable1189% (73)

- Internship ReportDocument40 paginiInternship ReportGwachee23% (13)

- Choke and Kill Manifold Brochure PDFDocument12 paginiChoke and Kill Manifold Brochure PDFtaloslamomia9417100% (1)

- Lokomotywy Folder en WebDocument17 paginiLokomotywy Folder en Webcosty_transÎncă nu există evaluări

- JLG Tow-Pro Series Boom LiftsDocument6 paginiJLG Tow-Pro Series Boom LiftsAdriano Alves SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global competition empowers customersDocument17 paginiGlobal competition empowers customersSaurabh AroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- DaewooDocument18 paginiDaewooapoorva498Încă nu există evaluări

- QPMC Rate CardsDocument9 paginiQPMC Rate CardsTarek TarekÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 Mercedes Maybach S ClassDocument20 pagini2016 Mercedes Maybach S ClassAshok Kumar K RÎncă nu există evaluări

- IV report-KERALA ELECTRICAL & ALLIED ENGINEERING CO. LTD, KOLLAMDocument15 paginiIV report-KERALA ELECTRICAL & ALLIED ENGINEERING CO. LTD, KOLLAMAmmu ChathukulamÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Survey of Probability ConceptsDocument23 paginiA Survey of Probability ConceptsWongsphat AmnuayphanÎncă nu există evaluări

- IP Rights Key to Auto Industry SuccessDocument14 paginiIP Rights Key to Auto Industry Successranjeetsingh2525Încă nu există evaluări

- How Do You Lift Cab On New Holland Skidsteer PDFDocument1 paginăHow Do You Lift Cab On New Holland Skidsteer PDFctdmnÎncă nu există evaluări