Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Am J Crit Care 2010 Jacobowski 421 30

Încărcat de

Beny HermawanDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Am J Crit Care 2010 Jacobowski 421 30

Încărcat de

Beny HermawanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Families in Critical Care

C OMMUNICATION IN

CRITICAL CARE: FAMILY

ROUNDS IN THE INTENSIVE

CARE UNIT

By Natalie L. Jacobowski, BA, Timothy D. Girard, MD, MSCI, John A. Mulder,

MD, and E. Wesley Ely, MD, MPH

Background Communication with family members of

patients in intensive care units is challenging and fraught

with dissatisfaction.

Objectives We hypothesized that family attendance at struc-

tured interdisciplinary family rounds would enhance commu-

nication and facilitate end-of-life planning (when appropriate).

Methods The study was conducted in the 26-bed medical

intensive care unit of a tertiary care, academic medical center

from April through October 2006. Starting in July 2006, families

were invited to attend daily interdisciplinary rounds where

the medical team discussed the plan for care. Family members

were surveyed at least 1 month after the patient’s stay in the

unit, completing the validated “Family Satisfaction in the

ICU” tool before and after implementation of family rounds.

Results Of 227 patients enrolled, 187 patients survived and 40

died. Among families of survivors, participation in family rounds

was associated with higher family satisfaction regarding fre-

quency of communication with physicians (P = .004) and sup-

port during decision making (P = .005). Participation decreased

satisfaction regarding time for decision making (P = .02).

Overall satisfaction scores did not differ between families who

attended rounds and families who did not. For families of

patients who died, participation in family rounds did not sig-

nificantly change satisfaction.

Conclusions In the context of this pilot study of family rounds,

certain elements of satisfaction were improved, but not over-

all satisfaction. The findings indicate that structured interdisci-

plinary family rounds can improve some families’ satisfaction,

whereas some families feel rushed to make decisions. More

work is needed to optimize communication between staff in

the intensive care unit and patients’ families, families’ compre-

hension, and the effects on staff workload. (American Journal

©2010 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses of Critical Care. 2010;19:421-430)

doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010656

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 421

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

C

omprehensive state-of-the-art care of patients in intensive care units (ICUs)

involves not only excellent medical treatment but also optimal communication

and interaction with the health care team. Family members, who frequently

must act as the surrogates for ICU patients, experience marked distress in situa-

tions characterized by poor communication and interpersonal interactions.1-6

For many patients and their families, this need for communication and interaction becomes

especially important when the transition from anticipation of cure to the realization of non-

survivability must be negotiated in the ICU, making the ICU team responsible for providing

a quality end-of-life experience for the patient and the patient’s family members.7

Although much attention has been given to the often is lacking.3,20 Failure to comprehend a diagno-

family conference separate from rounds,5,8-11 commu- sis, prognosis, or treatment occurs in 35% to 50%

nication may also be enhanced through routine of family members.21,22 Improved comprehension is

incorporation of families into daily interdisciplinary thought to be a base from which overall satisfaction

ICU rounds. Studies in pediatric12-14 and trauma15,16 can arise,1 making this deficit in understanding a

patients have suggested a beneficial significant impediment to optimal care. Thus, a

effect of including patients’ families “family rounds” approach, with nurses inviting and

Studies have in interdisciplinary rounds, and bringing the family into daily rounds, might facili-

suggested a exploration of the related practice of tate the earliest possible and most regular form of

bedside rounds shows the practice communication for all patients, not just those for

beneficial effect to be positively received by patients whom problems arise, such as the need for end-of-

of including as well.17,18 Studies of families’ experi- life discussions. On the other hand, such an

ences with end-of-life care in the approach of hearing the actual medical discussions

patients’ families ICU indicate a need for better com- on rounds could increase family members’ fear,

in interdisciplinary munication, as communication

deficits may contribute to family

confusion, and doubts about care.

We conducted this pilot investigation to explore

rounds. anxiety and depression,1,3,5,6 increased the effect of consistent, early communication through

risk of contradictory information the addition of a family component to interdiscipli-

from multiple physicians,19 and potential family nary rounds in the medical ICU, a setting in which

mistrust of physicians.5 Families desire more fre- this type of communication intervention has rarely

quent communication with nurses and physicians,6 been reported. This intervention will be referred to

and access to and comprehension of information as “family rounds” to focus on this 1 aspect of inter-

disciplinary rounds. While constructing this study,

we noted the importance of including both families

About the Authors

Natalie L Jacobowski is a medical student at the Vander- of patients who survive their ICU stay and families

bilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee. of patients who die during or shortly after an ICU

John A. Mulder is an assistant professor in the Department stay in the study. The needs of surviving patients

of Family Medicine at the Michigan State University

College of Human Medicine and the medical director and their families for communication can be neg-

for palliative care services for Spectrum Health in Grand lected because of the focus on communication in

Rapids, Michigan. Timothy D. Girard is an assistant pro- the end-of-life setting.23 We hypothesized that

fessor and E. Wesley Ely is a professor in the Division of

Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine and the implementation of family rounds would enhance

Center for Health Services Research in the Department communication and facilitate end-of-life planning

of Medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. (when appropriate) between families and the med-

Dr Girard is also a staff physician and Dr Ely is the asso-

ciate director for research in the Geriatric Research, ical team, leading to improved family satisfaction,

Education, and Clinical Center at the Department of Vet- especially with aspects of communication.

erans Affairs Medical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare

System, in Nashville.

Materials and Methods

Corresponding author: Natalie L. Jacobowski, BA, Vander- Study Design

bilt School of Medicine, 6th floor Medical Center East #6109,

Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN We conducted a before-after study during which

37232-8300 (e-mail: natalie.jacobowski@vanderbilt.edu). family satisfaction in the ICU was assessed before and

422 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

after implementation of a family rounds component of 1 to 5, with higher values indicating increased

of interdisciplinary rounds. satisfaction. In keeping with prior studies, responses

were converted to a score of 0 to 100 per question.25

Population of Patients The mean score for the 13 questions and 10 ques-

Two study investigators (N.J., A.D.) conducted tions provided the total score for

phone interviews with family members designated as each subdomain. The mean of

primary contacts for all patients admitted for longer these 2 subscores provided the

As many as 50% of

than 24 hours to the Vanderbilt University Medical total score. family members do

Center medical ICU, a 26-bed unit, before and after

the implementation of family rounds on July 7, 2006. Family Rounds Process not understand a

The study period included April 24, 2006, through The structure of family rounds diagnosis, progno-

October 31, 2006. Patients without a primary con- as a family communication com-

tact or whose primary contact did not understand ponent of daily interdisciplinary sis, or a treatment.

English sufficiently to complete the survey were rounds was developed through

excluded. Family members of patients enrolled multiple discussions with the physicians and nurses

before implementation of family rounds comprised of the ICU, with the following format settled upon.

the baseline group. Family members who attended Family rounds were added to the existing structure

rounds after implementation of family rounds com- of interdisciplinary rounds in the medical ICU,

prised the family rounds group. Upon admission to which occurred before regular visiting hours and

the ICU, patients’ families received a letter describing consisted of (1) nurses’ presentation of vital signs

the study and the phone surveys. For patients dis- and relevant events from the previous 24 hours, (2)

charged from the unit, surveys were completed within interns’ presentation of 24-hour events, assessment,

1 month following discharge. For patients who died and plan, complementing information provided by

in the unit, surveys were completed between 3 and the nurse, (3) upper level residents’ and fellows’

5 months following the death, allowing for a griev- refinement of 24-hour goals and treatment plan,

ing period for the families. At the time of the phone and (4) teaching provided by the attending physi-

call, the purpose of the survey was described again, cian to the treatment team. Two additional steps,

families were informed that the survey was voluntary which we define as family rounds, were added: (5)

and anonymous, and verbal consent was obtained. the attending physician provided a summary for the

Only 1 respondent was interviewed per patient, and family using understandable, lay language and (6)

no patient included in the baseline group was read- the family was offered an opportunity to ask ques-

mitted during the family rounds period. This study tions of the team. To limit extension of the time of

was reviewed by the institutional review board at rounds, each patient was allowed up to 2 family

Vanderbilt University and granted expedited review members at the bedside and if questions exceeded a

and approval with verbal consent obtained at the few minutes, the team invited the family to meet

time of interview. with them again after rounds for further discussion.

More extended family conferences

Survey Development and Administration did not occur for every patient,

The previously refined and validated Family but the standard medical ICU

The physician pro-

Satisfaction in the ICU (FS-ICU) survey24 was used procedure was to arrange such vided a summary for

in this study. The survey consisted of 2 subdo- conferences as needed because of

mains: care and decision making, which consisted complexity of illness or to facilitate

the family that used

of 13 and 10 questions, respectively. The Cronbach decision making. lay language, and

α coefficients for the 2 subscales were 0.92 and Families received an explana-

0.88, respectively, and the 2 subscales showed good tory letter and verbal explanation families were able

correlation with each other (Spearman ρ = 0.73, P < from the nurse upon admission, to ask questions.

.001), supporting their combination into a single orienting them to these procedures

scale with a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.94. The as well. It was essential that the nurses embraced

survey’s validity was demonstrated by a significant the concept of family rounds, as they would be the

correlation with results of the previously estab- ones helping bring families in and out of the ICU

lished Family-Quality of Death and Dying survey. in the morning and also would have the most fre-

Respondents rated their satisfaction with multiple quent interactions with families, which meant that

aspects of the patient’s care in the ICU and the the nurses were a primary influence to encourage

respondent’s experience during that time on a scale their patients’ families to attend family rounds.

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 423

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

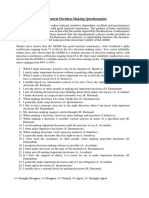

Table 1

Items related to communication on the Family

Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) survey

summary scores. Because responses on individual

How often nurses communicated to you about your family member’s survey items were strongly skewed (ie, most respon-

condition. dents rated their experiences “good” or “excellent”),

How often doctors communicated to you about your family member’s we also reduced each item to a dichotomous vari-

condition. able representing the highest level of satisfaction

(eg, “excellent” or “very supported”) versus less than

Willingness of ICU staff to answer your questions.

the highest level of satisfaction and compared these

How well ICU staff provided you with explanations that you understood.

variables using the χ2 test.

The honesty of information provided to you about your family member’s To explore potential interactions between the

condition. effect of family rounds and patients’ survival in the

How well ICU staff informed you what was happening to your family ICU, we included interaction terms in proportional

member and why things were being done. odds logistic regression models with individual FS-

The consistency of information provided to you about your family mem- ICU items as the dependent variables. In keeping

ber’s condition. with authoritative recommendations on the topic,26,27

Did you feel included in the decision-making process? no adjustments were made to our results to account

for multiple comparisons. Although this lack of

Did you feel supported during the decision-making process?

adjustment may increase the likelihood of a type I

When making decisions, did you have adequate time to have your con-

error, our approach of not making such adjustments

cerns addressed and questions answered?

avoids an unnecessary inflation of type II errors.

STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas),

Data Entry and Statistical Analysis and SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois)

For this pilot study, sample size was determined were used for data analysis, and a 2-sided 5% sig-

by available resources. Thus, we sought to enroll all nificance level was used for all statistical inferences.

eligible patients during the specified period of study.

Because our goal for this study was to assess the Results

efficacy of family rounds as a source of improved Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

satisfaction via better communication, we focused Among 402 families of survivors for whom

our analysis on specific items in the FS-ICU that we contact information was available, 234 respondents

deemed most relevant (Table 1). These questions (58%) completed the survey; among 67 families of

had a primary focus on communication with mem- deceased patients for whom contact information

bers of the ICU team, understanding and decision was available, 44 respondents (66%) completed the

making by family members, and frequency of con- survey. After we eliminated those who did not attend

tact with the ICU team. Although any family rounds despite this intervention’s avail-

The number of less specific to this study, the sum-

mative scores for decision making

ability at the time of their family member’s ICU

admission, 227 survey interviews of family members

families feeling and overall satisfaction were evalu- remained to be analyzed. Of these families, 187

ated as well, in keeping with prior were of patients discharged from the ICU and 40

“very supported” research.25 We also stratified all were of patients who died in the ICU. The break-

improved after analyses according to whether the down of those interviews is shown in Figures 1 and

patient survived to ICU discharge or 2. For patients who survived and those who died in

attending family died in the ICU, because we hypoth- the ICU, survey respondents during the baseline

rounds. esized that family members of phase were similar to respondents who attended

patients who died would have differ- family rounds, without significant differences in age,

ent interactions with ICU staff than would families race, or relationship to the patient (Table 2). Patients

of patients who survived, and therefore the effect of enrolled during the 2 study periods were similar

family rounds on satisfaction may differ according except that patients who survived during the family

to survival status of the patient. rounds phase had longer stays in the ICU than did

Baseline characteristics are presented by using patients who survived before implementation of

median and interquartile range for continuous vari- family rounds.

ables and proportions for categorical variables. We

used χ2 tests to compare categorical variables between Follow-Up Family Evaluations: Surviving Patients’

the study groups, and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney Families

2-sample rank-sum test to compare continuous vari- When families of surviving patients were asked

ables, including individual items on the FS-ICU and to rate “How often doctors communicated to you

424 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

223 patients

about your family member’s condition,” the number admitted >24 hours

of families who rated this central aspect of communi-

cation as “excellent” improved significantly (P = .004)

after the implementation of family rounds (Table 3).

Families also were asked about the support they 191 patients 32 patients died in the

received via the question: “Did you feel supported discharged intensive care unit

during the decision-making process?” The number

of families who reported feeling “very supported,”

the top value on the Likert scale, improved signifi-

cantly (P = .005) after families had the opportunity 52 without contact 5 without contact

information information

to attend family rounds. In contrast, the percentage

41 refused 9 refused

of family members who responded that they had

“more than enough time to have concerns addressed

and questions answered” during decision making

declined after implementation of family rounds 98 families surveyed 18 families surveyed

(P = .02). When all potential responses to this item

were compared before and after family rounds, results Figure 1 Flowchart shows the numbers of surveys conducted dur-

of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test indicated no signifi- ing the baseline phase, with detailed listing of whether the family

cant difference between groups (P = .19). All other was associated with a patient who had been discharged alive

items were rated similarly before and after implemen- from the intensive care unit or was associated with a patient who

died in the unit (designated as end-of-life).

tation of family rounds.

Follow-Up Family Evaluations: Deceased Patients’

Families

Among families of patients who died in the ICU, 403 patients

none of the FS-ICU items pertaining to communica- admitted >24 hours

tion were rated significantly better by respondents

who participated in family rounds than by families

who did not (Table 3). Families of deceased patients

who were in the family rounds group tended to report 344 patients 59 patients died in the

the highest level of satisfaction regarding “How discharged intensive care unit

often nurses communicated to you about your fam-

ily member’s condition” more often than did fami-

lies of deceased patients who did not participate in

81 without contact 19 without contact

family rounds (P = .11). Similarly, the number of

information information

family members of deceased patients who reported 127 refused 14 refused

the highest level of satisfaction regarding “willingness

of ICU staff to answer your questions” increased

after implementation of family rounds (P = .18).

136 families surveyed 26 families surveyed

89 at family rounds 22 at family rounds

Overall Measures of Satisfaction and Interactions 47 did not attend* 4 did not attend*

Neither the decision-making subscore nor the

total FS-ICU score differed significantly between

respondents who attended family rounds and Figure 2 Flowchart shows the numbers of surveys conducted after

implementation of family rounds, during the intervention phase,

respondents from before implementation of family with detailed listing of whether the family was associated with a

rounds (Table 3). Additionally, no significant inter- patient who had been discharged alive from the intensive care unit

actions were noted between the effect of family or was associated with a patient who died in the unit (designated as

rounds on family satisfaction and patients’ survival end-of-life) and whether the family attended family rounds.

in the ICU. *Families who did not attend family rounds despite the opportunity to do so were

excluded from all analyses.

Discussion

In this pilot before-after study, a family rounds family satisfaction but did result in significant

component during interdisciplinary rounds in the improvements in some aspects of family satisfaction

medical ICU did not affect the global measure of related to communication. Specifically, families of

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 425

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

Table 2

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Patient survived Patient died

Baseline Family rounds Baseline Family rounds

Characteristics (n = 98) (n = 89) P value (n = 18) (n = 22) P value

Patient

Age, median [interquartile range], y 57 [46-66] 55 [37-66] .45 62 [51-68] 56 [49-71] .94

Female, % 49 42 .31 56 50 .73

Race, % .61 .97

White 79 85 82 82

Black 12 10 18 18

Other 9 5 0 0

Admission diagnosis, % .11 .36

Cardiovascular 11 8 17 9

Respiratory 21 33 50 27

Neurological 11 16 6 9

Sepsis 14 10 0 18

Gastroenterological 12 18 6 9

Other 31 15 21 28

Days in intensive care unit, median 3 [2-5] 4 [3-8] .001 4 [2-6] 4 [3-9] .46

[interquartile range]

Full code status, % 97 93 .33 65 76 .23

Respondent

Age, y, % .41 .23

≥80 0 1 0 4

60-79 30 21 47 18

40-59 53 57 35 55

20-39 16 20 18 23

<20 1 1

Female, % 69 80 .10 61 77 .27

Race, % .56 .97

White 79 87 82 82

Black 13 10 18 18

Other 8 3

Relationship to patient, % .66 .33

Spouse/partner 49 49 72 50

Child 28 23 11 36

Parent 11 17 6 5

Other 12 11 11 9

discharged patients reported an increased frequency the scheduled opportunity to receive information

of communication. Additionally, although family and answers to questions. Past studies also have

rounds had been conceived as an efficient use of revealed a link between family satisfaction and psy-

time for both families and the medical team, the chological health.1,3,5,6 Hospitalization of a loved one

results indicated that more families perceived the in the ICU is a very stressful event for family mem-

time for decision making as inadequate after imple- bers, with nearly 3 out of every 4 family members

mentation of family rounds. struggling with anxiety and 1 in 3 showing signs of

Other researchers have evaluated patients’ per- depression.6,28 A proactive approach to bereavement

spectives of similar interventions such as bedside and implementation of a proactive communication

case presentations that brought the patient and fam- strategy leads to decreases in the frequency of post-

ily into the midst of rounds. Most patients preferred traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depressive

such bedside presentations.17,18 Studies of family symptoms.5 In our family rounds pilot study, this com-

inclusion in ICU rounds are limited,15,16 but the results munication began at admission, congruent with the

available indicate that patients’ families appreciated reported increased satisfaction with communication

426 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

Table 3

Effect of family rounds on family satisfaction

Patient survived Patient died

Historical Family rounds Historical Family rounds

Outcome (n = 98) (n = 89) P value (n = 18) (n = 22) P value

Individual items, % excellenta

Frequency of nurse communication 64 57 .30 33 59 .11

Frequency of physician communication 38 60 .004 50 43 .66

Willingness to answer questions 55 59 .58 33 55 .18

Understandable explanations 54 54 .98 39 41 .90

Honesty of information 61 58 .74 53 48 .74

Informative regarding treatment 56 56 .95 39 52 .40

Consistency of information 51 53 .81 33 55 .18

Included in decision making 66 76 .12 77 82 .71

Supported in decision making 49 69 .005 61 73 .44

Adequate time for questions 40 23 .02 39 41 .90

Summary scores, median

[interquartile range]

Decision-making subscore 83 [65-93] 85 [74-93] .67 75 [63-88] 78 [73-90] .18

Total survey score 85 [70-95] 88 [75-95] .65 74 [62-92] 82 [72-94] .26

a “% excellent” indicates the proportion of respondents who gave the survey item the highest rating, that is, expressed the highest level of satisfaction.

when prognostic information is provided within a format and a frequently updated picture of their

shorter time interval.29 By addressing some of these loved one’s condition.13,15 These rounds also helped

key components of family satisfaction, family rounds prepare families for more in-depth discussions that

could minimize psychological distress in the stress- were sometimes necessary later in the day to meet

ful ICU environment (especially if family members their reported need for more time in decision mak-

who feel rushed by such an approach are encour- ing than might be possible during rounds. However,

aged to have family conferences later in the day to the effect of family rounds on knowledge and com-

allow more time for decision making). Simultane- prehension was not studied in this investigation

ously, subsequent studies of family inclusion should beyond families’ summary statements about access

consider the potential for families to feel intimidated to and satisfaction with information. As comprehen-

or overwhelmed in the setting of daily rounds and sion is a central aspect of good communication, it

should explore family comfort in that setting and warrants more extensive attention in future studies.

any potential effects on families’ levels of stress and Studies of families of patients with end-of-life

anxiety. This important balance must be explored experiences have documented a need for informa-

in future research. tion early and often,7,22 and inadequacies of infor-

This pilot study highlights that family satisfac- mation and communication may impede removal

tion with communication may hinge on receipt of of life support, leading to a prolonged dying process

adequate knowledge to improve family members’ and longer stays for patients.32 Interdisciplinary inclu-

comprehension and aid in surrogate decision mak- sion of the ICU medical care team during family

ing.1,5,20,21,25,28,30,31 Inadequate comprehension is reported rounds may reduce communication obstacles by

in 30% to 50% of patients’ families,21,22,28 a statistic fostering more cohesive care with better integration

that we felt necessitated that the structure of family of palliative care,33 yet the pace of these rounds and

rounds include having the physician provide the the inclusion of medical terminology amid the dis-

families with a 1- or 2-minute summary in lay lan- cussions between doctors and nurses could also

guage. Family rounds initiated brief, structured, and increase communication problems.

consistent communication within the first 24 hours Our study included only English-speaking

of admission, providing families a realistic, real-time patients. This necessitates further study of the

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 427

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

application of family rounds with non–English- limited sensitivity to detect a difference from before

speaking families as alterations in translation during to after implementation of family rounds. Addition-

interpreted interactions can adversely affect commu- ally, the study size—determined by restricted

nication, complicating both the transmission of resources and time available to conduct this pilot

knowledge and emotional support.34 study—was small, especially regarding patients with

In addition to examining the success end-of-life experiences, and the small number of

Families of dis- of content transmission in these participants may have impaired our ability to observe

charged patients conversations, studies of patient- overall changes in satisfaction. The study did not

physician relationships have shown have enough power to assess for differences between

reported an that styles of interpersonal commu- family members of living versus deceased patients.

increased frequency nication influence satisfaction.35,36 The refusal rate of families in study participa-

Studies in the ICU also have made tion warrants exploration. High baseline levels of

of communication. apparent a need to improve the satisfaction may point to a selection bias because

quality of communication.9,10 Future family members without contact information or

research also should evaluate the influence of the who refused to participate most likely are different

style and nature of the communication itself on sat- from families who responded to the survey, and the

isfaction of patients’ families. families who responded may represent a population

From the perspective of the ICU nurses, 2 of the most likely to attend and benefit from family

most significant obstacles to providing end-of-life rounds, even though demographically attendees

care are multiple physicians with discordant opin- and nonattendees were not significantly different.

ions about the plan of care and multiple family Because Vanderbilt University Medical Center serves

members contacting the staff instead of communi- a diverse population, other factors probably influ-

cating with 1 designated team member.19 From the enced family members’ ability and willingness to

perspective of the ICU care team, attention to com- attend family rounds, such as socioeconomic status,

munication and palliative care can lead to improved availability to be at the hospital at the time of rounds,

nurse-assessed quality of death in the ICU.37 In the geographic factors (many patients and their families

case of end-of-life care, nurses experienced distress live hours away from the hospital), and comfort

and decreased satisfaction with quality of care when and experience with the medical system. The rate of

they perceived care to be overly aggressive given the nonattendance is a limitation of this study, so these

patient’s expected prognosis,38,39 and the Critical Care factors should be explored.

Medicine Task Force 2004-2005 identified poor Attention also should be given to the level of

communication as a major source of stress for staff.40 nurse engagement in family rounds and nurse-

Although those issues were not explored formally in perceived barriers to successful family rounds, because

our study, family rounds may be a forum to address the level of family participation may depend on

these issues, providing components of suggested how well families are informed about and encour-

interventions,41 including a systemic framework to aged to attend family rounds by the bedside nurse

support integration of palliative care and attitudinal with whom they interact during the day.

change regarding communication Other limitations of this study should be dis-

Family rounds given the increased, regular interac- cussed. This was a single-center study, so future

tion with patients’ families. multicenter work is needed to assess the effects of

did not affect the Why did this study not show family rounds in other settings. Although no other

global measure of global improvements in satisfaction major changes were noted in our routine ICU prac-

among patients’ family members? tices during the course of the study, it is possible

family satisfaction. Several important factors must be that improvements in satisfaction were confounded

considered when addressing this by unmeasured factors such as time spent in further

intriguing question. As seen in other studies using communications during the rest of the day. In future

the FS-ICU,4,25,31,42 family members in the baseline work, particular attention should be given to the

group reported high satisfaction in general, thus time nurses and physicians spend communicating

improvements in satisfaction with family rounds medical updates to patients’ families as well as the

could have been difficult to detect because the high effect on nursing work flow and productivity during

baseline ratings may have caused a ceiling effect. the day. Different ICU team members differ with

Combined with the limited number of questions respect to their reactions to family rounds,38,43 neces-

on the FS-ICU that targeted aspects likely to be sitating exploration of the effects of family rounds

affected by family rounds, our study most likely had on all members of the team.

428 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

Conclusions 2. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Meeting the needs

of intensive care unit patient families: a multicenter study.

ICU patients’ and families’ satisfaction and com- Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):135-139.

prehension of the course of critical illness increas- 3. Azoulay E, Sprung CL. Family-physician interactions in the

intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(11):2323-2328.

ingly are recognized as relevant measures of outcome 4. Heyland D, Cook D, Rocker G, et al. Decision-making in the

and benchmarks of high-quality ICU care. Family ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Inten-

sive Care Med. 2003;29(1):75-82.

members participate in decision making, represent- 5. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communica-

ing the voice of the patient, and suffer significant tion strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in

the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469-478.

distress when inadequately educated and supported 6. Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, et al. Symptoms of anxiety

during a loved one’s ICU care. In this pilot investi- and depression in family members of intensive care unit

patients before discharge or death: a prospective multicen-

gation, including a family component in daily inter- ter study. J Crit Care. 2005;20:90-96.

disciplinary rounds appeared to be a potential means 7. Mosenthal AC. Palliative care in the surgical ICU. Surg Clin

North Am. 2005;85:303-313.

by which to improve some elements of satisfaction, 8. Azoulay E. The end-of-life family conference: communication

including support during decision making and fre- empowers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):803-804.

9. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Studying com-

quency of communication with physicians. Yet, an munication about end-of-life care during the ICU family

important minority of respondents reported inade- conference: developing a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17(3):

147-160.

quate time for decision making. 10. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Missed oppor-

Global satisfaction was not changed by the tunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in

the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:

implementation of family rounds in this study, and 844-849.

concern was raised about a potential negative per- 11. White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Lo B, Curtis JR.

Prognostication during physician-family discussions about

ception regarding having adequate time for decision limiting life support in intensive care units. Crit Care Med.

making. A need remains to explore further the impact 2007;2007(35):442-448.

12. Latta L, Dick R, Parry C, Tamura G. Parental responses to

of family rounds on family members’ psychological involvement in rounds on a pediatric inpatient unit at a

outcomes, family rounds’ ability to affect family teaching hospital: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):

292-297.

members’ comprehension and knowledge, the use 13. Lewis C, Knopf D, Chastain-Lorber K, et al. Patient, parent,

and effects of physicians’ differing communication and physician perspectives on pediatric oncology rounds.

J Pediatr. 1988;112(3):378-384.

styles and approaches, factors influencing family 14. Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, Gonzalez del Rey

attendance at family rounds, and the effect of fam- J, DeWitt TG. Family-centered bedside rounds: a new

approach to patient care and teaching. Pediatrics. 2007;119:

ily rounds on an ICU team’s workload. 829-832.

15. Mangram A, Mccauley T, Villarreal D, et al. Families’ percep-

tion of the value of timed daily “family rounds” in a trauma

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ICU. Am Surg. 2005;71(10):886-891.

We thank the director of the medical intensive care unit, 16. Schiller WR, Anderson BF. Family as a member of the trauma

Art Wheeler, MD, and the nurse manager of the medical rounds: a strategy for maximized communication. J Trauma

intensive care unit, Julie Foss, RN, MSN, for their support Nurs. 2003;10(4):93-99.

in the implementation of this research. Additionally, we 17. Lehmann LL, Brancati FL, Chen M-C, Roter D, Dobs AS. The

thank Andrea Dugas, MD, for her assistance in conducting effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions

phone surveys of family members. of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1150-1155.

18. Wang-Cheng R, Barnsas G, Sigmann P, Riendl P, Young M.

Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(4):284-287.

During the course of this research, Dr Girard was sup- 19. Beckstrand RL, Kirchhoff KT. Providing end-of-life care to

ported in part by the National Institutes of Health patients: critical care nurses’ perceived obstacles and sup-

(AG034257), the Hartford Geriatrics Health Outcomes portive behaviors. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(5):395-403.

Research Scholars Award Program, the Vanderbilt Physi- 20. Azoulay E, Pochard F. Communication with family members

cian Scientist Development Program, and the Veterans of patients dying in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit

Affairs Tennessee Valley Geriatrics Research, Education Care. 2003;9:545-550.

and Clinical Center. Dr Ely was supported in part by the 21. Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of

intensive care unit patients experience inadequate commu-

National Institutes of Health (AG027472) and the Veter-

nication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):3116-3117.

ans Affairs Tennessee Valley Geriatrics Research, Educa- 22. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Arich C, et al. Family par-

tion and Clinical Center. ticipation in care to the critically ill: opinions of families

and staff. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1498-1504.

23. Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidelines for evidence-

based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134:835-843.

eLetters

24. Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Heyland D, Curtis JR.

Now that you’ve read the article, create or contribute to an

Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfac-

online discussion on this topic. Visit www.ajcconline.org

tion in the ICU (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):

and click “Respond to This Article” in either the full-text or

271-279.

PDF view of the article.

25. Heyland D, Rocker G, Dodeck P, et al. Family satisfaction

with care in the intensive care unit: results of a multiple

center study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(7):1413-1418.

26. Perneger T. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments.

REFERENCES BMJ. 1998;316(7139):1236-1238.

1. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Impact of a family 27. Rothman K. No adjustments are needed for multiple com-

information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided parisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1(1):43-46.

to family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J 28. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Half the family mem-

Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:438-442. bers of intensive care unit patients do not want to share in

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 429

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

the decision-making process: a study in 78 French intensive 37. Curtis JR, Treecy PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative

care units. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(9):1832-1838. and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement inter-

29. LeClaire M, Oakes J, Weinert C. Communication of prognos- vention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:269-275.

tic information for critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;128(3): 38. Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on

1728-1735. the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collabora-

30. Cohen S, Sprung CL, Sjokvist P, et al. Communication in tion, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med.

end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units. 2007;35(2):422-429.

Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1215-1221. 39. Ho KM. The involvement of intensive care nurses in end-of-

31. Heyland D, Rocker G, O’Callaghan C, Dodeck P, Cook D. life decisions: a nationwide survey. Intensive Care Med.

Dying in the ICU: perspectives of family members. Chest. 2005;31:668-673.

2003;124(1):392-397. 40. Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice

32. Gerstel E, Engelberg RA, Koepsell T, Curtis JR. Duration of guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered

withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit and intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medi-

association with family satisfaction. Am J Respir Crit Care cine task force. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605-622.

Med. 2008;178:798-804. 41. Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Integrating

33. Curtis JR. Caring for patients with critical illness and their palliative and critical care: description of an intervention.

families: the value of an integrated team. Respir Care. 2008; Crit Care Med. 2008;34(11 suppl):2380-2387.

53(4):480-487. 42. Gries CJ, Curtis JR, Wall RJ, Engelberg RA. Family member

34. Pham K, Thornton J, Engelberg RA, Jackson J, Curtis JR. satisfaction with end-of-life decision making in the ICU.

Alterations during medical interpretation of ICU family con- Chest. 2008;133:704-712.

ference that interfere with or enhance communication. 43. Levy CR, Ely EW, Payne K, et al. Quality of death and dying

Chest. 2008;134(1):106-116. in two medical ICUs: perceptions of family and clinicians.

35. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, Chest. 2005;127(5):1775-1783.

and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA.

1999;282(6):583-589.

36. Napoles AMN, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J, O’Brien H,

To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact The

Stewart AL. Interpersonal processes of care and patient InnoVision Group, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656.

satisfaction: do associations differ by race, ethnicity, and Phone, (800) 899-1712 or (949) 362-2050 (ext 532); fax,

language? Health Serv Res. 2009;44(4):1326-1344. (949) 362-2049; e-mail, reprints@aacn.org.

430 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, September 2010, Volume 19, No. 5 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

Communication in Critical Care: Family Rounds in the Intensive Care Unit

Natalie L. Jacobowski, Timothy D. Girard, John A. Mulder and E. Wesley Ely

Am J Crit Care 2010;19 421-430 10.4037/ajcc2010656

©2010 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

Published online http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/

Personal use only. For copyright permission information:

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/cgi/external_ref?link_type=PERMISSIONDIRECT

Subscription Information

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/

Information for authors

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/misc/ifora.xhtml

Submit a manuscript

http://www.editorialmanager.com/ajcc

Email alerts

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/etoc.xhtml

The American Journal of Critical Care is an official peer-reviewed journal of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

(AACN) published bimonthly by AACN, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Telephone: (800) 899-1712, (949) 362-2050, ext.

532. Fax: (949) 362-2049. Copyright ©2016 by AACN. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 5, 2018

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Bookshelf NBK153098Document238 paginiBookshelf NBK153098Beny HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 16Document166 paginiJurnal 16Beny HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 9Document312 paginiJurnal 9Beny HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 12Document142 paginiJurnal 12Beny HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 9Document312 paginiJurnal 9Beny HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of An Emergency Department Dedicated Midtrack Area On Patient FlowDocument6 paginiThe Effect of An Emergency Department Dedicated Midtrack Area On Patient FlowBeny HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Homeroom Guidance Learner'S Development Assessment: School Year 2020 - 2021 KindergartenDocument3 paginiHomeroom Guidance Learner'S Development Assessment: School Year 2020 - 2021 KindergartenRouselle Umagat Rara100% (1)

- NLR - Vol 8 - No-2Document330 paginiNLR - Vol 8 - No-2Ankit AmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- EDUC 213 - Final 5Document8 paginiEDUC 213 - Final 5Fe Canoy100% (2)

- Valuing Vs Recognizing EmployeesDocument5 paginiValuing Vs Recognizing EmployeesSush BiswasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Career Development WorkbookDocument15 paginiCareer Development WorkbookDheeraj BahlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Literacy and Financial Behavior of Management Undergraduates of Sri LankaDocument6 paginiFinancial Literacy and Financial Behavior of Management Undergraduates of Sri LankaRod SisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enrichment Activity MAS RELEVANT COSTINGDocument3 paginiEnrichment Activity MAS RELEVANT COSTINGarlyn ajero100% (1)

- Unit 17. ULC - Assignment - 17BMDocument19 paginiUnit 17. ULC - Assignment - 17BMMinh LợiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ogl 481 Pro-Seminar I Pca-Human Resource Frame Worksheet 2Document2 paginiOgl 481 Pro-Seminar I Pca-Human Resource Frame Worksheet 2api-545456362Încă nu există evaluări

- Homeroom ReportDocument15 paginiHomeroom ReportReese Arvy MurchanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4th SemDocument70 pagini4th SemSandeep KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business EthicsDocument12 paginiBusiness EthicsGil DelgadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Management: Assignment ONDocument5 paginiPrinciples of Management: Assignment ONshivaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Biases of Investors and Financial Risk ToleranceDocument6 paginiCognitive Biases of Investors and Financial Risk TolerancelaluaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organizational Structure Redesign For An Aviation Services Company - A PaperDocument24 paginiOrganizational Structure Redesign For An Aviation Services Company - A PapernanditaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pmqa 3Document3 paginiPmqa 3YoushÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9.decision TheoryDocument51 pagini9.decision Theorysrishti bhatejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- GDMS FinalDocument1 paginăGDMS FinalJoysri RoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Systematic Problem Solving & Decision Making Method: Kepner Tregoe Problem AnalysisDocument16 paginiA Systematic Problem Solving & Decision Making Method: Kepner Tregoe Problem AnalysisRahul_regal100% (1)

- Land Evaluation ASLE DefinitionsDocument13 paginiLand Evaluation ASLE DefinitionsKani ManikandanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ST - Scholasticas College Tacloban: Basic Education DepartmentDocument13 paginiST - Scholasticas College Tacloban: Basic Education DepartmentThereseÎncă nu există evaluări

- IE 405 ProblemSet 4 Solutions SharedDocument3 paginiIE 405 ProblemSet 4 Solutions SharedHasan AydınÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brainstorming and NGTDocument21 paginiBrainstorming and NGTkabbirhossainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Success Factors For Creating SuperbDocument14 paginiCritical Success Factors For Creating Superbali al-palaganiÎncă nu există evaluări

- ql7 STRDocument41 paginiql7 STRDanish ButtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orlove 1980 - Ecological AnthropologyDocument40 paginiOrlove 1980 - Ecological AnthropologyJona Mae VictorianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning Function of Management PPMDocument6 paginiPlanning Function of Management PPMCalvince OumaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIand HRMframeworkDocument21 paginiAIand HRMframeworkJohn AstliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review Built To ServeDocument16 paginiBook Review Built To ServegajamaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rapid Risk Assessment of Acute Public Health EventsDocument44 paginiRapid Risk Assessment of Acute Public Health EventsdinahajjarÎncă nu există evaluări