Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cognitive1 PDF

Încărcat de

laleesamTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cognitive1 PDF

Încărcat de

laleesamDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Random Thoughts . . .

WHY STUDENTS FAIL TESTS

1. INEFFECTIVE STUDYING

Richard M. Felder

T

Rebecca Brent

here’s some unhappiness in the faculty lounge today. are almost as ineffective as (4). Rereading old material and

Let’s eavesdrop. cramming for tests are easy strategies to use—which is one

“I just gave my first midterm exam and thought I was reason they’re so popular—and they may help students on

giving the students an early Christmas present—I expected memory tests given soon after the cramming, but they don’t

an average in the 80s, and they came in with a 56. I don’t lead to long-term remembering and even less to understand-

understand how most of them ever got this far.” ing. If a test requires more than short-term memorization, the

students who use those strategies probably won’t care too

“I know, right? I ask questions straight from my much for their grades.

lectures or the text, and the students act like they’ve never

seen anything like it in their lives.” • Rereading leads to illusions of knowing.

“Yeah—I put a problem on my last midterm almost Another drawback of studying by rereading is that it is seri-

exactly like one in the homework with just a few minor ously misleading. When students look at a problem solution

changes, and half of them couldn’t even start the solution, over and over again, they can easily convince themselves that

let alone finish.” they understand the solution method well enough to apply it

to related problems. That’s an illusion—one of several com-

And so on. To listen to the professors, many of their students mon student self-deceptions called illusions of knowing or

don’t belong in engineering school and couldn’t survive for illusions of competence. The students may be able to replicate

a day as professionals. Mysteriously, though, most of them that exact solution on a test soon after they memorized it, but

will go on to graduate, get jobs, and do just fine. So what’s

going on with those test grades?

In the last two decades cognitive science has provided some Rebecca Brent is an education consultant

specializing in faculty development for ef-

clues about what might be going on. The problems fall into fective university teaching, classroom and

two broad categories: some involve ineffective studying and computer-based simulations in teacher

others relate to ineffective teaching. This column concerns

education, and K-12 staff development in lan-

guage arts and classroom management. She

problems of the first type, and a later column will examine the has published articles on a variety of topics

second category. What follows draws heavily on two excellent including writing in undergraduate courses,

cooperative learning, public school reform,

books: Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning,[1] and effective university teaching.

and A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science.[2]

• Ways in which students commonly study for exams Richard M. Felder is Hoechst Celanese

don’t work. Professor Emeritus of Chemical Engineering

at North Carolina State University. He is co-

Many students rely heavily on one or more of four strate- author of Elementary Principles of Chemical

gies to study for exams: (1) rereading the text and class Processes (Wiley, 2015) and numerous articles

on chemical process engineering and engi-

handouts and notes, maybe underlining or highlighting parts neering and science education. Many of his

they consider important; (2) rereading homework and old test publications can be seen at <www.ncsu.edu/

effective_teaching>.

problem solutions; (3) studying mainly the night before the

exam, and (4) not studying at all. There’s no need to discuss Drs. Felder and Brent are coauthors of Teach-

ing and Learning STEM: A Practical Guide

(4)—students either know it doesn’t work or they find out on (Jossey-Bass, 2016).

their first exam, and if they stay on that path, they deserve

the consequences. Less obviously, it turns out that (1)–(3) © Copyright ChE Division of ASEE 2016

Chemical Engineering Education, 50(2), 151-152 (2016).

if the test problem is even slightly different they may not be if the students are given evidence that those methods lead to

able to solve it at all. Even if the identical problem shows up better learning and higher grades, they are likely to cling to

on a test a more than a day or two after the cramming session, their mistaken sense that retrieval practice is slowing them

many students will have forgotten the solution. down and hurting their academic performance.

So if rereading and cramming are ineffective test prepara- As the Rolling Stones sagely observed in a different context,

tion strategies, what are better ones? We’ll describe several, you can’t always get what you want, but sometimes you get

but we’ll begin with a short oversimplified description of the what you need. Varied retrieval practice imposes desirable

learning process from a cognitive science viewpoint. difficulties, strengthening memory traces of material in long-

• For course material to be truly “learned,” it must be term storage and bolstering cues for its subsequent retrieval.

stored in long-term memory in such a way that it can That doesn’t mean all difficulties are desirable: if instructors

subsequently be retrieved and transferred to new contexts. impose tasks that students lack the background knowledge

and skills to complete with a reasonable effort or that don’t

Most information that comes in through your senses is strengthen skills targeted in the instructor’s learning objec-

filtered out before you are conscious of it. If it gets through tives, nothing useful is likely to result. If retrieval practice

that initial sensory filter, it goes into your working memory, tasks are reasonable and address targeted skills, however, the

where a control center in your brain evaluates it. If it meets resulting learning gains more than compensate for the added

certain criteria (which we’ll describe in the next column), it is struggles the tasks impose on the students.

integrated into your long-term memory as a memory trace—an

interconnected network of nerve cells. If it isn’t integrated, it • How to help your students improve their performance

is lost to you—you won’t be able to recall it later because in on tests.

effect you never knew it. The story doesn’t end there, however. Give your students retrieval practice by imbedding low-

Even if information makes it into long-term memory, its trace stakes quizzes and self-tests in your class sessions and online

may initially be weak and hard to access, but each subsequent lessons. Make your assignments and exams cumulative,

retrieval strengthens the network and makes the information covering not just material introduced since the last test but

more accessible when it is later needed. This phenomenon bringing back material from earlier in the course. Tell your

provides the basis for a much better approach to studying students that when they read a text or article, they shouldn’t

than rereading and cramming. just read through it like a novel but should periodically stop

• Varied retrieval practice is the way to study. and quiz themselves, restating text content in their own

words, and instead of just rereading problem solutions they

A powerful strategy for strengthening learning is retrieval should try to solve the problems without looking back at the

practice—recalling information without looking back at it. solutions. When they get stuck on something, they may look

Spaced retrieval practice (letting enough time elapse between back at the text or problem solution, unstick themselves, and

successive retrievals for some forgetting to occur) is far more then go back to answering self-tests and solving problems on

effective than massed practice (rapid repetition of the same their own. When they can work through the text or problem

material). Learners can increase the effectiveness of retrieval without looking, they’re ready to move on to something else.

practice even more by using interleaving, periodically jump- Then they should do it again after some time passes. When

ing from one topic or type of problem or solution method to you make these suggestions to the students, acknowledge that

another rather than focusing at length on one topic or type or adopting them may not be easy, and be ready to cite evidence

method at a time, and elaborating, restating retrieved mate- supporting them from References 1 and 2. By taking these

rial in their own words and connecting it to prior knowledge. steps, you will not only help your students succeed in your

• Varied retrieval practice imposes desirable difficulties course, you’ll help them become self-directed learners in their

on learners. subsequent courses and professional careers.

Extensive research has made it clear that varied retrieval

practice leads to much better learning and test performance REFERENCES

than rereading and cramming can produce, but what it doesn’t 1. Brown, P.C., H.L. Roediger III, and M.A. McDaniel, Make It Stick:

do is make the learner’s life easier. On the contrary, trying to The Science of Successful Learning, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press

(2014)

remember information without looking back at the source and 2. Oakley, B.A. , A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science

to solve problems without looking back at solutions is hard, (Even If You Flunked Algebra), New York: Tarcher/Penguin (2014) p

and students who use those strategies often believe they are

learning less and getting lower grades because of them. Even

All of the Random Thoughts columns are now available on the World Wide Web at

http://www.ncsu.edu/effective_teaching and at www.che.ufl.edu/CEE.

152 Chemical Engineering Education

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Navigating The Bumpy Road To Student-Centered InstructionDocument13 paginiNavigating The Bumpy Road To Student-Centered InstructiondspssmpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning by Solving Solved ProblemsDocument2 paginiLearning by Solving Solved ProblemspapaasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Random Thoughts - . .: The Ten Worst Teaching MistakesDocument2 paginiRandom Thoughts - . .: The Ten Worst Teaching MistakesfamtaluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching For Quality Learning-J.biggsDocument36 paginiTeaching For Quality Learning-J.biggsKevin Dito GrandhikaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Field Study 2 Episode 3Document9 paginiField Study 2 Episode 3Gina May Punzalan PanalanginÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructional Project 3 - Research PaperDocument5 paginiInstructional Project 3 - Research PaperkayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Identifying and Solving Common Problems of Classroom TeachingDocument11 paginiIdentifying and Solving Common Problems of Classroom TeachingRyan SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3Document3 paginiModule 3Vencent Jasareno CanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mock 2 Paper 2 KeyDocument9 paginiMock 2 Paper 2 KeyDavinia LongoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Learning StylesDocument5 paginiLesson Plan Learning StylesmajabajapajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning How To Learn A Model For TeachiDocument8 paginiLearning How To Learn A Model For TeachiAngel Amerie LorenianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Getting Students to Understand Deep LearningDocument2 paginiGetting Students to Understand Deep LearningDanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grad Ed Lesson Plan - Ela - AstDocument18 paginiGrad Ed Lesson Plan - Ela - Astapi-610122953Încă nu există evaluări

- Active Learning IntroductionDocument6 paginiActive Learning Introductionprueba_usuarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stepp Review Activity 1Document6 paginiStepp Review Activity 1api-281839323Încă nu există evaluări

- TrigonometryDocument20 paginiTrigonometryteachopensourceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre-Observation Formkunakorn15feb21Document1 paginăPre-Observation Formkunakorn15feb21api-456126813Încă nu există evaluări

- Extending Our Assessments: Homework and TestingDocument22 paginiExtending Our Assessments: Homework and TestingRyan HoganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching Freshman Engineering Students To Solve Hard ProblemsDocument16 paginiTeaching Freshman Engineering Students To Solve Hard Problemslooyd alforqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Model For Instructional DesignDocument6 paginiA Model For Instructional DesigngangudangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q.1 How Strategies Serve As Guidelines For Teaching Science? Explain Some Thoughts of Scientists On InquiryDocument21 paginiQ.1 How Strategies Serve As Guidelines For Teaching Science? Explain Some Thoughts of Scientists On InquiryKashaf SheikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tallonj TeachlikeachampionnotesDocument3 paginiTallonj Teachlikeachampionnotesapi-403444340Încă nu există evaluări

- Educators File Year 2003Document4 paginiEducators File Year 2003sszmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prof Ed 13 - Episode 2Document7 paginiProf Ed 13 - Episode 2Apelacion L. VirgilynÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3.1 - Creswell, J, (2012) - Educational Research 58-63Document7 pagini3.1 - Creswell, J, (2012) - Educational Research 58-63Sergio Yepes PorrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creswell Identifying A Research ProblemDocument6 paginiCreswell Identifying A Research ProblemLEIDY CRUZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analyze Learners and ContextsDocument4 paginiAnalyze Learners and Contextsapi-487935250Încă nu există evaluări

- MODULE 2 Phases and Process of Curriculum Development Learning Activities/Exercises 1Document7 paginiMODULE 2 Phases and Process of Curriculum Development Learning Activities/Exercises 1Claudia Taneo InocÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 BVS LA2 SevillaDocument3 pagini11 BVS LA2 SevillaGinnie Beb SevillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Quizzes Motivate Students to Engage with Course MaterialDocument7 paginiReading Quizzes Motivate Students to Engage with Course MaterialLaolao Auring GaborÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assesment To Improve Learning in HEDocument50 paginiAssesment To Improve Learning in HEErvin Tri SuryandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educ 5312-Research Paper Template 1 1Document8 paginiEduc 5312-Research Paper Template 1 1api-357803051Încă nu există evaluări

- Assignment: Fundamental of ElementsDocument7 paginiAssignment: Fundamental of ElementsanusarannyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task 2. Teacher DevelopmentDocument3 paginiTask 2. Teacher DevelopmentLaurie Rua100% (1)

- Models For TeachingDocument5 paginiModels For Teachingecha mashudiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Problem Based Learning (PBL) Why PBL? How It Works and What It AchievesDocument8 paginiProblem Based Learning (PBL) Why PBL? How It Works and What It AchievesmichaeleslamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Cultures CommunitiesDocument31 paginiLearning Cultures CommunitiesEFL Classroom 2.0Încă nu există evaluări

- Teach Like A Champion NotesDocument26 paginiTeach Like A Champion NotesmmsastryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Observation Lesson Plan 1 ModelDocument3 paginiObservation Lesson Plan 1 Modelapi-302412972Încă nu există evaluări

- Strategies For Teaching Large Classes: Brought To You byDocument22 paginiStrategies For Teaching Large Classes: Brought To You byazmirnizahÎncă nu există evaluări

- SupplementaryC SCOPEANDDELIMITATIONOFRESEARCHDocument14 paginiSupplementaryC SCOPEANDDELIMITATIONOFRESEARCHVince Joshua AbinalÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Test 36: Archives Forums B-Schools Events MBA VocabularyDocument3 paginiEnglish Test 36: Archives Forums B-Schools Events MBA VocabularycomploreÎncă nu există evaluări

- PBL Presentation-7 12 11revisedDocument46 paginiPBL Presentation-7 12 11revisedapi-240535342Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 3Document5 paginiLesson 3api-607526690Încă nu există evaluări

- Skill Review Sheet - Questioning: Graduate Standards - AITSLDocument13 paginiSkill Review Sheet - Questioning: Graduate Standards - AITSLapi-309403984Încă nu există evaluări

- General Methods of Teaching (EDU301) : Question# 1 (A) Cooperative LearningDocument6 paginiGeneral Methods of Teaching (EDU301) : Question# 1 (A) Cooperative LearningsadiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cep Lesson Plan Quote IntroductionsDocument10 paginiCep Lesson Plan Quote Introductionsapi-643118051Încă nu există evaluări

- Problem Based Learning and ApplicationsDocument9 paginiProblem Based Learning and ApplicationsArielle EstefaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 LiMo Sem1 Summary of StuEvalsDocument5 pagini7 LiMo Sem1 Summary of StuEvalsgongfutuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8601 R 3SDocument20 pagini8601 R 3Swaseemhasan85Încă nu există evaluări

- Innovative Teaching MethodsDocument14 paginiInnovative Teaching MethodsumashankaryaligarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Research 1 Quarter 1 - Module 12: Scope and Delimitation of ResearchDocument18 paginiPractical Research 1 Quarter 1 - Module 12: Scope and Delimitation of ResearchFaith Galicia Belleca100% (3)

- Francis Sam L. SantañezDocument4 paginiFrancis Sam L. SantañezFrancis Sam SantanezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tutorials in Introductory Physics (Physics Education Research User S Guide)Document9 paginiTutorials in Introductory Physics (Physics Education Research User S Guide)Ana PaulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Center of Excellence For Teacher EducationDocument5 paginiCenter of Excellence For Teacher EducationKhim Bryan RebutaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teacher Work SampleDocument7 paginiTeacher Work Sampleapi-295655000Încă nu există evaluări

- Active Learning An IntroductionDocument6 paginiActive Learning An IntroductionHà MùÎncă nu există evaluări

- BP 7Document2 paginiBP 7api-328102237Încă nu există evaluări

- Active Learning An IntroductionDocument6 paginiActive Learning An IntroductionswarnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Princípio Das Casas Dos PombosDocument3 paginiPrincípio Das Casas Dos PomboslaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maths Lesson PlanDocument141 paginiMaths Lesson PlanlaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Princípio de Inclusão Exclusão e Princípio Da ReflexãoDocument8 paginiPrincípio de Inclusão Exclusão e Princípio Da ReflexãolaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Yoram Hazony The Philosophy of HeDocument3 paginiReview Yoram Hazony The Philosophy of HelaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced Hypnotic Writing PDFDocument116 paginiAdvanced Hypnotic Writing PDFbijayr100% (1)

- Pigeonhole 2Document4 paginiPigeonhole 2Ml PhilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis FulltextDocument132 paginiThesis Fulltextdormouse1Încă nu există evaluări

- Textos InglesDocument20 paginiTextos IngleslaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- IJETT-46-2-Design-Modeling-Fabrication-GenevaDocument5 paginiIJETT-46-2-Design-Modeling-Fabrication-GenevaMohamed muzamilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samurai Wisdom Lessons From Japan's Warrior CultureDocument257 paginiSamurai Wisdom Lessons From Japan's Warrior CulturelaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Army Research Institute - Combat Leaders' GuideDocument229 paginiArmy Research Institute - Combat Leaders' Guideanon-868435100% (1)

- fm6 22Document188 paginifm6 22Daniel PerrefortÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conjugal Union What Marriage Is and Why It MattersDocument152 paginiConjugal Union What Marriage Is and Why It MatterslaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Man in The MirrorDocument31 paginiThe Man in The MirrorlaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- fm6 22Document188 paginifm6 22Daniel PerrefortÎncă nu există evaluări

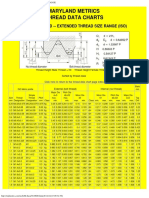

- Austain Technical Information Sheet Metric Pitch TableDocument1 paginăAustain Technical Information Sheet Metric Pitch TablelaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Army Research Institute - Combat Leaders' GuideDocument229 paginiArmy Research Institute - Combat Leaders' Guideanon-868435100% (1)

- The Ethical Foundations of MarxismDocument233 paginiThe Ethical Foundations of MarxismlaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Threads - Metric ISO 724Document5 paginiThreads - Metric ISO 724laleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review Homiletical Plot The LowryDocument5 paginiBook Review Homiletical Plot The LowrylaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pagini6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Stephen's Guide To The Logical FallaciesDocument22 paginiStephen's Guide To The Logical FallaciesHugo Zavala RodríguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arduino CNC ShieldDocument6 paginiArduino CNC Shieldlaleesam100% (1)

- Tolerancia de Rosca Metrica 6G PDFDocument20 paginiTolerancia de Rosca Metrica 6G PDFRodrigo Tikim0% (3)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pagini6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Bachelor Thesis 3D Printer Electronics DesignDocument92 paginiBachelor Thesis 3D Printer Electronics DesignlaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- AT89C51 Data SheetDocument17 paginiAT89C51 Data SheetrishindiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- UManitoba SQ3R Reading StrategyDocument3 paginiUManitoba SQ3R Reading StrategylaleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Threads - Metric ISO 724Document5 paginiThreads - Metric ISO 724laleesamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classroom Language 2Document14 paginiClassroom Language 2Lany BalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acdemic Calender 2023 24Document2 paginiAcdemic Calender 2023 24souryadeepmitraÎncă nu există evaluări

- EARIST Achieves Remarkable Year in Instruction, Research, Extension and AdministrationDocument124 paginiEARIST Achieves Remarkable Year in Instruction, Research, Extension and AdministrationMaimai NeriÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Development of Social Welfare in The PhilippinesDocument13 paginiThe Development of Social Welfare in The Philippinespinakamamahal95% (20)

- Srilaxmi Cs SopDocument2 paginiSrilaxmi Cs Sopashsailesh100% (3)

- Personal: 1oo Job Interview QuestionsDocument4 paginiPersonal: 1oo Job Interview QuestionsAnderson Andrey Alvis RoaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mapping Out For Heritage FrameworkDocument19 paginiMapping Out For Heritage FrameworkEdward Jr ChoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- GATE Cutoff 2022: Previous Year Paper-Wise Qualifying Marks, Opening and Closing Ranks For Iits & NitsDocument17 paginiGATE Cutoff 2022: Previous Year Paper-Wise Qualifying Marks, Opening and Closing Ranks For Iits & NitsR037 Sai Neeraj Yadav PeerlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2B. Jelaskan Menenai Penerapan Behavioural Principles Dalam Belajar: A) Mastery Learning B) Group ConsequenceDocument3 pagini2B. Jelaskan Menenai Penerapan Behavioural Principles Dalam Belajar: A) Mastery Learning B) Group ConsequenceJosephine PhebeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction On The Study of GlobalizationDocument7 paginiIntroduction On The Study of GlobalizationJezalen GonestoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft Campbell Town 2040 Ls PsDocument100 paginiDraft Campbell Town 2040 Ls PsDorjeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sun Moon & ShadowDocument56 paginiSun Moon & Shadowmelissa lorena cordoba100% (1)

- Dokumen 5Document1 paginăDokumen 5Balamurugan HÎncă nu există evaluări

- Signed Durango 9R Resolution On EquityDocument2 paginiSigned Durango 9R Resolution On EquitySimply SherrieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Backward-Design-Cells - Template OriginalDocument4 paginiBackward-Design-Cells - Template Originalapi-283163390100% (3)

- Capella Workout Club Indemnity FormDocument2 paginiCapella Workout Club Indemnity FormbrussellwkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iit Jee Bansal Notes PDFDocument3 paginiIit Jee Bansal Notes PDFPradeep Singh Maithani25% (32)

- Rotter'S Locus of Control Scale: Personality TestDocument12 paginiRotter'S Locus of Control Scale: Personality TestMusafir AdamÎncă nu există evaluări

- PFPDocument5 paginiPFPSouvik Boral0% (1)

- T&H1 Chapter 6Document27 paginiT&H1 Chapter 6Gerry Louis Ordaneza GallanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Performance Monitoring and Coaching FormDocument2 paginiSample Performance Monitoring and Coaching FormFernadez Rodison100% (2)

- Education and Certification: David WarrenDocument5 paginiEducation and Certification: David WarrendavemightbeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume and Qualifications 1Document7 paginiResume and Qualifications 1Mapaseka PhuthehangÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4et1 01r Rms 20220303Document27 pagini4et1 01r Rms 20220303Ramya RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ielts Writing Practise Test 11 17th August 2019Document3 paginiIelts Writing Practise Test 11 17th August 2019Ivan SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- District No AC NameDocument32 paginiDistrict No AC NameTricolor C A100% (1)

- Small Samples in Interview BasedDocument18 paginiSmall Samples in Interview BasedJasminah MalabiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic Act No. 7610 protects children from abuseDocument10 paginiRepublic Act No. 7610 protects children from abuseBernice DumaoangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Master Assessor - Trainer GuideDocument338 paginiMaster Assessor - Trainer GuideBME50% (2)

- Think 101 X Course InfoDocument4 paginiThink 101 X Course InfoTiago AugustoÎncă nu există evaluări