Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Case Digest

Încărcat de

Sachuzen230 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

197 vizualizări7 paginiCase Digest

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

RTF, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentCase Digest

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca RTF, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

197 vizualizări7 paginiCase Digest

Încărcat de

Sachuzen23Case Digest

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca RTF, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 7

Nacu vs CSC

Facts:

PEZA issued a memorandum prohibiting its employees from

charging and collecting overtime fees from PEZA registered

enterprises. EBCC filed a complaint against Nacu for allegedly

charging it overtime fees despite the memorandum order. During

the investigation, Ligan attested, among others, that the overtime

fees went to Nacu's group, and that, during the time Nacu was

confined in the hospital, she pre-signed documents and gave

them to him. Nacu denied that the signatures appearing on the

ten overtime billing statements were hers.

Issue:

Whether or not the signatures appearing on the overtime billing

was of Nacu.

Ruling: YES!

Margallo, a co-employee who holds the same position as Nacu,

also identified the latter's signatures on the SOS. Such testimony

deserves credence. It has been held that an ordinary witness may

testify on a signature he is familiar with. Anyone who is familiar

with a person's writing from having seen him write, from carrying

on a correspondence with him, or from having become familiar

with his writing through handling documents and papers known to

have been signed by him may give his opinion as to the

genuineness of that person's purported signature when it

becomes material in the case

Rules of Court, Rule 130, Sec. 50 provides:SEC. 50. Opinion of

ordinary witnesses. -- The opinion of a witness for which proper

basis is

given, may be received in evidence regarding --

xxxx(b) A handwriting with which he has sufficient familiarity.

Heirs of Ochoa vs GS Transport

Facts:

Jose Marcial died in an accident on board a taxicab owned and

operated by G & S. A complaint for damages was filed against the

latter. The RTC adjudged G & S guilty of breach of contract of

carriage and awarded the victim damages for loss of earning

capacity. The CA affirmed the decision of RTC, but modified the

award on the ground that on the ground that the income

certificate issued by Jose Marcial’s employer, the United States

Agency for International Development (USAID), is self-serving,

unreliable and biased, and that the same was not supported by

competent evidence such as income tax returns or receipts.

G & S file an MR arguing that the USAID Certification used as

basis in computing the award for loss of income is inadmissible in

evidence because it was not properly authenticated and identified

in court by the signatory thereof.

Issue:

Whether or not authentication of the USAID certification is

admissible.

Ruling:

It therefore becomes necessary to first ascertain whether the

subject USAID Certification is a private or public document before

this Court can rule upon the correctness of its admission and

consequent use as basis for the award of loss of income in these

cases.

Sec. 19, Rule 132 of the Rules of Court classifies documents as

either public or private, viz: Sec. 19. Classes of Documents – For

the purpose of their presentation in evidence, documents are

either public or private. Public documents are:

(a) The written official acts, or records of the official acts

of the sovereign authority, official bodies and tribunals,

and public officers, whether of the Philippines, or of a

foreign country;

The USAID is an official government agency of a foreign country,

the United States. Hence, Cruz, as USAID’s Chief of the Human

Resources Division in the Philippines, is actually a public officer.

Apparently, Cruz’s issuance of the subject USAID Certification was

made in the performance of his official functions, he having

charge of all employee files and information as such officer. In

view of these, it is clear that the USAID Certification is a public

document pursuant to paragraph (a), Sec. 19, Rule 132 of the

Rules of Court. Hence, and consistent with our above discussion,

the authenticity and due execution of said Certification are

already presumed.

It is true that before a private document offered as authentic be

received in evidence, its due execution and authenticity must first

be proved. However, it must be remembered that this

requirement of authentication only pertains to private documents

and “does not apply to public documents, these being admissible

without further proof of their due execution or genuineness. Two

reasons may be advanced in support of this rule, namely: said

documents have been executed in the proper registry and are

presumed to be valid and genuine until the contrary is shown by

clear and convincing proof; and, second, because public

documents are authenticated by the official signature and seals

which they bear and of which seals, courts may take judicial

notice.”

RE: COMPLAINT OF CONCERNED MEMBERS OF CHINESE

GROCERS ASSOCIATION AGAINST JUSTICE SOCORRO B.

INTING OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

A.M. OCA IPI No. 10-177-CA-J, April 12, 2011

Facts:

CGA is the owner of a parcel of land. Sometime in 2008, Dela Cruz

filed a petition for the issuance of a new owner’s duplicate copy

alleging that the old owner’s duplicate copy had been misplaced.

Dela Cruz based his petition on his interest as the vendee of the

property, as evidenced by a Deed Of Absolute Sale, allegedly

signed by Ang Bio, representative of CGA. The court granted the

petition. The CGA filed a petition against the judge contending

that the latter acted in gross neglect in granting Dela Cruz’s

petition. The claim that the deed should have aroused tje judge

suspicion as it was allegedly signed by Ang Bio who died on 2001.

Issue:

Ruling:

The uncertified death certificate cannot be admitted as

evidence.

It is settled that if a document is a public document, to

prove its contents, there is a need to present a certified

copy of this document, issued by the public officer in

custody of the original document.

In this case, Complainant had not presented any other

evidence to support the charge of misconduct leveled

against J. The complainants only offered as evidence

a mere photocopy of its agent’s Certificate of Death.

Clearly it is lack of certification from the in-charged

public officer. Thus, it is inadmissible as evidence, and

is considered a mere scrap of paper without any

evidentiary value. In the absence of proof of

misconduct, the presumption that respondent regularly

performed her duties will prevail.

G.R. No. 178551, October 11, 2010

ATCI OVERSEAS CORPORATION, AMALIA G. IKDAL

AND MINISTRY OF PUBLIC HEALTH-KUWAIT

PETITIONERS, VS. MA. JOSEFA ECHIN,

RESPONDENT.

Facts:

Echin was hired by ATC In behalf of the Ministry of Public Health of

Kuwait. Echin was employed as medical technologist under a two-

year contract. The contract provides further that Echin is to

undergo a probationary period of 1 year. Echin was dismissed, the

latter not having passed the probationary period. Echin later filed

a petition for illegal dismissal in the NLRC. The petitioner maintain

that they should not be held liable since the employment contract

provides that her employment shall be governed by the Civil

Service Law and Regulations of Kuwait. They allege that it is a

patent error to apply the labor code provisions on probationary

employment.

Issue:

Whether or not kuwaiti laws and regulation should apply in this

case.

Ruling:

It is hornbook principle, however, that the party invoking

the application of a foreign law has the burden of proving

the law.

The Philippines does not take judicial notice of foreign laws,

hence, they must not only be alleged; they must be proven.

To prove a foreign law, the party invoking it must present a

copy thereof and comply with Sections 24 and 25 of Rule

132 of the Revised Rules of Court.

To prove the Kuwaiti law, petitioners submitted the

following: MOA between respondent and the Ministry, as

represented by ATCI, which provides that the employee is

subject to a probationary period of one (1) year and that the

host country's Civil Service Laws and Regulations apply; a

translated copy (Arabic to English) of the termination letter

to respondent stating that she did not pass the probation

terms, without specifying the grounds therefor, and a

translated copy of the certificate of termination

These documents, whether taken singly or as a whole, do

not sufficiently prove that respondent was validly

terminated as a probationary employee under Kuwaiti civil

service laws. Instead of submitting a copy of the

pertinent Kuwaiti labor laws duly authenticated and

translated by Embassy officials thereat, as required

under the Rules, what petitioners submitted were

mere certifications attesting only to the correctness of

the translations of the MOA and the termination letter

which does not prove at all that Kuwaiti civil service

laws differ from Philippine laws and that under such

Kuwaiti laws, respondent was validly terminated

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- SubpoenaDocument4 paginiSubpoenaromeo n bartolomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discrimination in The Workplace Research LLDocument5 paginiDiscrimination in The Workplace Research LLHardik ShettyÎncă nu există evaluări

- SATA GLOBE BPM PVT LTD OFFER LETTERDocument4 paginiSATA GLOBE BPM PVT LTD OFFER LETTERSachin ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- pcl14 Chap 1 en CaDocument41 paginipcl14 Chap 1 en CaNAOMI0% (1)

- Constitutional Law Case DigestsDocument316 paginiConstitutional Law Case DigestsOsfer Gonzales100% (1)

- Crim AnswerDocument12 paginiCrim AnswerPM CUÎncă nu există evaluări

- 13 People V Hayag DigestedDocument1 pagină13 People V Hayag DigestedHiroshi CarlosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aluad Vs AluadDocument2 paginiAluad Vs AluadSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Validity of foreign divorce decree in intestate estate caseDocument1 paginăValidity of foreign divorce decree in intestate estate caseangelyn susonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Novulis - Organizational Structure - Revised - The Strategist - 05012024Document16 paginiNovulis - Organizational Structure - Revised - The Strategist - 05012024neelimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Tandoy Drug Case Best Evidence RuleDocument1 paginăPeople Vs Tandoy Drug Case Best Evidence RuleSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Lomboy, SalesandLeaseDocument8 paginiLomboy, SalesandLeaseZonix LomboyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The NKTI Medical Laboratory: National Kidney and Transplant InstituteDocument1 paginăThe NKTI Medical Laboratory: National Kidney and Transplant InstituteMiiMii Imperial AyusteÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAN MIGUEL UNION VS. LAGUESMADocument2 paginiSAN MIGUEL UNION VS. LAGUESMAAnonymous 5MiN6I78I0Încă nu există evaluări

- Heirs of The Estate of JBL Reyes Vs City ofDocument3 paginiHeirs of The Estate of JBL Reyes Vs City ofkarljoszefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument2 paginiCase DigestLance Cedric Egay Dador100% (1)

- Chinabank Vs OrtegaDocument1 paginăChinabank Vs OrtegaJohndel CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mariategui vs. CA Marriage DisputeDocument232 paginiMariategui vs. CA Marriage Disputemichael jan de celisÎncă nu există evaluări

- MAURICIO C. ULEP vs. THE LEGAL CLINIC Bar Matter No. 553 June 17, 1993Document2 paginiMAURICIO C. ULEP vs. THE LEGAL CLINIC Bar Matter No. 553 June 17, 1993Andy BÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saez Vs Macapagal-ArroyoDocument15 paginiSaez Vs Macapagal-Arroyovanessa_3Încă nu există evaluări

- Francisco Jr. vs. Nagmamalasakit Na Mga Manananggol NG Mga Manggagawang Pilipino Inc. 415 SCRA 44 November 10 2003Document270 paginiFrancisco Jr. vs. Nagmamalasakit Na Mga Manananggol NG Mga Manggagawang Pilipino Inc. 415 SCRA 44 November 10 2003Francis OcadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knights of Rizal Vs DmciDocument1 paginăKnights of Rizal Vs DmciArrianne ObiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSC rules on experience requirements for promotionDocument4 paginiCSC rules on experience requirements for promotionSimeon Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legaspi V City of CebuDocument6 paginiLegaspi V City of CebuIsaiah CalumbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heirs of Ochoa Vs GS TransportDocument3 paginiHeirs of Ochoa Vs GS TransportSachuzen23100% (1)

- Thoughts On Career TheoriesDocument10 paginiThoughts On Career TheoriesJudy MarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ma. Rosario Santos-Concio Vs Raul M. GonzalezDocument5 paginiMa. Rosario Santos-Concio Vs Raul M. GonzalezJuris Formaran0% (1)

- Judicial Affidavit RODRIGO SWERTEDocument4 paginiJudicial Affidavit RODRIGO SWERTEGamy GlazyleÎncă nu există evaluări

- BAR QnA BankingDocument4 paginiBAR QnA BankingCzarina BantayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nakpil Vs Valdes (A.c. No. 2040. March 4, 1998)Document1 paginăNakpil Vs Valdes (A.c. No. 2040. March 4, 1998)roa yusonÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAGAYAN VALLEY DRUG CORPORATION vs. CIRDocument3 paginiCAGAYAN VALLEY DRUG CORPORATION vs. CIRSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Abella Vs Cabañero, 836 SCRA 453, G.R. No. 206647, August 9, 2017Document2 paginiAbella Vs Cabañero, 836 SCRA 453, G.R. No. 206647, August 9, 2017Inday LibertyÎncă nu există evaluări

- State Investment House Vs IacDocument1 paginăState Investment House Vs IacSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Andamo Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument8 paginiAndamo Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Watiwat - RapeDocument11 paginiPeople Vs Watiwat - RapegeorjalynjoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- AWB BueroDocument52 paginiAWB BueroAlma Raluca MihuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heirarchy of CourtsDocument3 paginiHeirarchy of CourtsPaulyn MarieÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 212690 Spouses Romeo Pajares and Ida T. Pajares, Petitioners Remarkable Laundry and Dry Cleaning, Represented by Archemedes G. SolisDocument13 paginiG.R. No. 212690 Spouses Romeo Pajares and Ida T. Pajares, Petitioners Remarkable Laundry and Dry Cleaning, Represented by Archemedes G. Solisxeileen08100% (1)

- Aluad Vs AluadDocument1 paginăAluad Vs AluadSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Navaro Marcos Vs Heirs of NavaroDocument2 paginiNavaro Marcos Vs Heirs of NavaroSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Dayot Vs ShellDocument2 paginiDayot Vs ShellSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Checklist OHS 4801 2001Document5 paginiChecklist OHS 4801 2001sjarvis5Încă nu există evaluări

- Abella V BarriosDocument9 paginiAbella V BarriosDessa Ruth ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atty Suspended for Fraudulently Acquiring Client's SharesDocument1 paginăAtty Suspended for Fraudulently Acquiring Client's Sharesmei atienzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mancol Vs DBPDocument8 paginiMancol Vs DBPAlexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atty Violates Notarial Law in Fake Deed CaseDocument4 paginiAtty Violates Notarial Law in Fake Deed Casegrace caubangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bolos VDocument3 paginiBolos VAnonymous NqaBAyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quasi-Judicial Power of BSP Monetary BoardDocument100 paginiQuasi-Judicial Power of BSP Monetary BoardPauline Eunice Lobigan100% (1)

- CIVPRODigest Jurisdiction Rule3Document23 paginiCIVPRODigest Jurisdiction Rule3Francisco MarvinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labrel Case Digests (Set 1)Document21 paginiLabrel Case Digests (Set 1)jamilove20100% (1)

- Mamiscal vs. AbdullahDocument3 paginiMamiscal vs. AbdullahmavslastimozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1Document6 pagini1Jc GalamgamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3&.epublir of Tbe Bihppine% Supreme Qtourt::fflanDocument18 pagini3&.epublir of Tbe Bihppine% Supreme Qtourt::fflanEarl TabasuaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- RP LIBEL LAWSDocument5 paginiRP LIBEL LAWSBenedict-Karen BaydoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Occena Vs IcaminaDocument2 paginiOccena Vs IcaminaRian Lee TiangcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carale vs. AbarintosDocument13 paginiCarale vs. AbarintosRustom IbañezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personal Determination by Judge - Examination of WitnessDocument58 paginiPersonal Determination by Judge - Examination of WitnessLen Vicente - FerrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest 20-22Document4 paginiCase Digest 20-22Aki LacanlalayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angeles v. Gutierrez - OmbudsmanDocument2 paginiAngeles v. Gutierrez - OmbudsmanLeslie OctavianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statutory Construction ReviewerDocument11 paginiStatutory Construction ReviewerChaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Research - Case Digest - Hernandez v. CA, GR No. 126010Document1 paginăLegal Research - Case Digest - Hernandez v. CA, GR No. 126010LawrenceAlteza100% (1)

- PULUMBARITDocument3 paginiPULUMBARITeds billÎncă nu există evaluări

- St. James School labor union case ruling on quorum existenceDocument5 paginiSt. James School labor union case ruling on quorum existenceDeus DulayÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs BerangDocument3 paginiPeople Vs BerangClaudia Rina LapazÎncă nu există evaluări

- EB Villarosa v. Judge BenitoDocument6 paginiEB Villarosa v. Judge BenitoStephen CabalteraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case11 Dalisay Vs Atty Batas Mauricio AC No. 5655Document6 paginiCase11 Dalisay Vs Atty Batas Mauricio AC No. 5655ColenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Armovit v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 154559, October 5, 2011Document2 paginiArmovit v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 154559, October 5, 2011KcompacionÎncă nu există evaluări

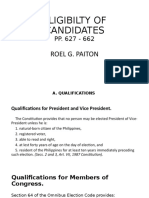

- Admin Law - Eligibility of Candidates PaitonDocument46 paginiAdmin Law - Eligibility of Candidates PaitonAejay Villaruz BariasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modesto vs. Urbina 633 SCRA 383, October 18, 2010Document20 paginiModesto vs. Urbina 633 SCRA 383, October 18, 2010juan dela cruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dagdag VDocument16 paginiDagdag Vchichille benÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cordon vs. BalicantaDocument13 paginiCordon vs. BalicantaAdrianne BenignoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maritime DigestDocument13 paginiMaritime DigestanjisyÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. L-32476. October 20, 1970 DigestDocument1 paginăG.R. No. L-32476. October 20, 1970 DigestMaritoni RoxasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Olbes v. BuemioDocument2 paginiOlbes v. BuemioTon RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2nd LIST OF CASES: Philippine Case Law SummariesDocument4 pagini2nd LIST OF CASES: Philippine Case Law SummariesGF Sotto100% (1)

- Digest of Bersamin CasesDocument4 paginiDigest of Bersamin Casesmarie deniegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nacu vs CSC Ruling on Signature IdentificationDocument4 paginiNacu vs CSC Ruling on Signature IdentificationSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Bank vs Construction Firm forged check disputeDocument14 paginiBank vs Construction Firm forged check disputecarlo moraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument8 paginiCase DigestSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument8 paginiCase DigestSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument5 paginiCase DigestSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Remedial DigestDocument6 paginiRemedial DigestSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument8 paginiCase DigestSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Karen E. Salvacion vs. Central Bank of The PhilippinesDocument16 paginiKaren E. Salvacion vs. Central Bank of The PhilippinesSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Bernales Vs SambaanDocument4 paginiBernales Vs SambaanSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Bernales Vs SambaanDocument2 paginiBernales Vs SambaanSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument5 paginiCase DigestSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument3 paginiCase DigestSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Macarrubo Vs MacarruboDocument3 paginiMacarrubo Vs MacarruboSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Nacu vs CSC Ruling on Signature IdentificationDocument4 paginiNacu vs CSC Ruling on Signature IdentificationSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- The People of The Philippines Vs TandoyDocument1 paginăThe People of The Philippines Vs TandoySachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- LRA Vs NavidadDocument6 paginiLRA Vs NavidadSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- The People of The Philippines Vs TandoyDocument1 paginăThe People of The Philippines Vs TandoySachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- LRA Vs NavidadDocument6 paginiLRA Vs NavidadSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Samaneigo V FerrerDocument2 paginiSamaneigo V FerrerSachuzenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The People of The Philippines Vs TandoyDocument1 paginăThe People of The Philippines Vs TandoySachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- LRA Vs NavidadDocument6 paginiLRA Vs NavidadSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- Samaneigo V FerrerDocument2 paginiSamaneigo V FerrerSachuzen23Încă nu există evaluări

- North Dakota Parental Responsibility Initiative For The Development of Employment Program (PRIDE) - 2007 CSG Innovation Award WinnerDocument7 paginiNorth Dakota Parental Responsibility Initiative For The Development of Employment Program (PRIDE) - 2007 CSG Innovation Award Winnerbvoit1895Încă nu există evaluări

- Mandu Labour Law Sem 4Document12 paginiMandu Labour Law Sem 4vfjhfvkjhvÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAP Audit Guide Human ResourcesDocument9 paginiSAP Audit Guide Human ResourcesQuanTum Chinprasitchai100% (1)

- Professional Bodies, Trade Unoins and Other OrganizaitonsDocument8 paginiProfessional Bodies, Trade Unoins and Other Organizaitonschroma warframeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zahra Asghar Ali CVDocument3 paginiZahra Asghar Ali CVZahraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promoting Mental Wellbeing at Work: Quick Reference GuideDocument8 paginiPromoting Mental Wellbeing at Work: Quick Reference Guideapi-18815167Încă nu există evaluări

- Alcantara vs. CA - DigestedDocument6 paginiAlcantara vs. CA - DigestedMaria Alice Corominas Lim-InglesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sony INFODocument13 paginiSony INFOUrvashi PetkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBRE Hotel Insights The Vietnam MarketDocument5 paginiCBRE Hotel Insights The Vietnam MarketVu Le MinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of District Industries CentreDocument19 paginiRole of District Industries CentreakjsdkuwÎncă nu există evaluări

- StaffingDocument24 paginiStaffingAzmi RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engineering Students' Academic and On-The-Job Training Performance Appraisal AnalysisDocument5 paginiEngineering Students' Academic and On-The-Job Training Performance Appraisal AnalysisJulina Jerez AbadiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sahara Profile 2016Document18 paginiSahara Profile 2016wessam_thomasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Local Consultant to Link MSEs with FSPsDocument2 paginiLocal Consultant to Link MSEs with FSPsGetachew HussenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strike or LockoutDocument19 paginiStrike or Lockoutanamika2023Încă nu există evaluări

- Rural Development Programmes and Externalities: A Study of Seven Villages in Tamil NaduDocument155 paginiRural Development Programmes and Externalities: A Study of Seven Villages in Tamil NaduSathish BabuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chicago Journal of Sociology 2014Document143 paginiChicago Journal of Sociology 2014SocialSciences UChicagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meaning of Work and Career Theories SeminarDocument11 paginiMeaning of Work and Career Theories SeminarZyrille PadillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virtual TimeClock Network Administrators Quick Reference PDFDocument20 paginiVirtual TimeClock Network Administrators Quick Reference PDFbacharnajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case StudyDocument9 paginiCase StudyEdzer Ortiz Mandani100% (1)

- Rekayasa Faktor ManusiaDocument21 paginiRekayasa Faktor Manusiarikapuspitadewi namakuÎncă nu există evaluări