Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Last Taboo-Israel's Bomb Revisited (169-175)

Încărcat de

Luciano Dondero0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

8 vizualizări6 paginiThe Last Taboo

Titlu original

The Last Taboo-Israel's Bomb Revisited [169-175]

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThe Last Taboo

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

8 vizualizări6 paginiThe Last Taboo-Israel's Bomb Revisited (169-175)

Încărcat de

Luciano DonderoThe Last Taboo

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 6

“Js it really possible to redesign and buttress the nonproliferation regime, as the

Iranian case requires, while leaving Israel’ nuclear capacity an untouched

taboo? Is it healthy for Israeli democracy or slobal ‘secutity to continue with the.

ale of nuclear opacity?”

The Last Taboo:

Israel’s Bomb Revisited

AVNER COHEN

weapon state. It was the sixth nation in the

world—and the first in the Middle East—to

develop and acquire nuclear weapons. Indeed,

while exact figures are speculative, Israel's nuclear

forces are believed to be (in qualitative terms at

least) more like those of France and the United

Kingdom than India’ and Pakistan’,

Yet Israel's code of conduct and discourse in the

nuclear field differs distinctly from the other estab-

lished nuclear weapon states. Unlike the seven

acknowledged nuclear nations—the five de jure

nuclear weapon states under the nuclear Non-

Proliferation Treaty (NPT) (the United States, Rus

sia, United Kingdom, France, and China), and the

two de facto nuclear weapon states outside the NPT

(India and Pakistan)—Israel has never advertised

or even admitted its nuclear status. Since Prime

Minister Levi Eshkol stated in the mid-1960s that

“Israel will not be the first nation to introduce

nuclear weapons to the Middle East,” all eight of his

successors have not moved from this ambiguous

declaratory stance. The formula has become so

anachronistic that Israeli leaders rarely invoke it

anymore, Nobody—in or out of Israel—cares to ask

Israeli leaders uncomfortable questions about the

nation’s nuclear status. Israel's once big secret is

regarded now as the world’s worst-kept secret, so

there is no point in asking.

Nearly 40 years after Israel crossed the nuclear

threshold its leaders remain faithful to the same

code of secrecy, nonacknowledgement, and censor-

ship imposed at the time they initiated the program,

This makes the Israeli bomb conspicuous by its

I= everyone agrees, is an established nuclear

AVNER COHEN, «senior fellow atthe Center for International

and Security Studies at the Univesity of Maryland, is author of

the forthcoming Israels Last Taboo

169

very absence. The bomb is Israel’ last taboo. Israelis

call this taboo—this code of conduct and dis-

course—amimut, Hebrew for opacity or ambiguity.

The problem, from which the international com-

munity can no longer afford to look away, is

whether Israel’s nuclear opacity today presents a

barrier to reform of the global nonproliferation

regime. As the world confronts Iran’ nuclear ambi-

tion, and along with it the need to strengthen non-

proliferation norms and enforcement, there are

many in the international community who are ask-

ing, “And what about Israel?” Is it really possible to

redesign and buttress the nonproliferation regime,

as the Iranian case requires, while leaving Israel’

nuclear capacity an untouched taboo? Is it healthy

for Israeli democracy or global security to continue

with the path of nuclear opacity?

THE ISRAELI EXCEPTION

Amimut is Israel’s most distinguished legacy to

the nuclear age. As a national policy it sets the

ground rules for Israel's nuclear conduct and dis-

course. At home, under this policy Israel treats its

entire nuclear complex as one “black box.” That

Israel’ big secret is no longer a secret makes no dif-

ference to the government’ policy. Not only are

Israeli officials prohibited from saying anything

about the nation’s nuclear complex, but even pri-

vate citizens (such as journalists or authors) are for-

bidden. The office of the military censor enforces

the taboo: it is a violation in Israel even to use the

words “nuclear weapons” in print (in reference to

Israeli weapons). Instead, the term is substituted

with euphemisms such as “nuclear option,”

“nuclear potential,” “nuclear capability,” or other

softer words such as “strategic weapons.” The prac-

tice is silly—everyone recognizes that—but under

the current policy it continues. A host of military

170 * CURRENTHISTORY * April 2005

censors continues to be paid to delete forbidden “n-

words,” or to preface them with the legitimizing

phrase, “according to foreign reports

Nuclear opacity is more than an official policy or

a strategic posture. It has also a strong—some

would say critical—societal component. Opacity

has become the Israeli way of seeing and doing

things nuclear, The governments policy and the

taboo as a societal response are two sides of the

same coin, This intimate linkage between official

policy and public taboo makes the nuclear issue a

domestic Israeli oddity, a sort of paradox. On this

particular issue, the Israeli citizenry defers its fun-

damental democratic rights, and it does so in a most

democratic fashion.

Ultimately, the opacity is larger than just an

Israeli affair; itis a sore problem for the nonprolif-

eration regime. Nuclear weapons, and the ways they

are acknowledged, proliferated, regulated, and con-

trolled by nations, are an international issue, From

this perspective, too, the Israeli bomb is an oddity,

an international anomaly that has also turned out

to be a taboo of sorts. In Washington, and subse-

quently in other Western capitals, the Israeli bomb

has become a most sensitive issue, almost untouch-

able. What had started as a bilateral arrangement of

“don't ask, dont tell,” has evolved over decadles into

a policy under which the United States treats Israel

asa special (and unique) nuclear case, Under this

policy, the United States has exercised its diplomatic

influence and power to ignore and shield the Israeli

case, Israel is treated as an exception, somehow

exempt from the nonproliferation regime that

applies to everyone else.

Friends and foes of Israel (and of the United

States) have to reckon with this aura of exception-

alism, For friends itis a matter of political embar-

rassment; for foes it highlights the double standard,

and inequality of America’s unevenhanded approach

to nonproliferation. Ultimately, this attitude of

exceptionalism has allowed Israel to enjoy the fruits

of the nonproliferation regime without being in it,

and surely without paying its dues to it. As a non-

NPT signatory (one of three, the two others are India

and Pakistan), Israel remains outside (most of) the

nonproliferation regime’ international oversight and,

accountability obligations.

Initially, the attitude of looking the other way

from the Israeli nuclear case stemmed from a sin-

cere effort to ease the burden of having to deal with

nuclear Israel on the Us nonproliferation policy, as

well as on the international community at large

Today, almost four decades after Israel became a

nuclear weapon state and seven years after India

and Pakistan openly declared their nuclear status,

the conduct of opacity and the taboo underlying it

are still with us. But the international context is,

becoming more problematic. Rather than merely

preserving the status quo, the nonproliferation

regime today is viewed as a tool critically needed

ut currently inadequate to prevent more states

“rom acquiring nuclear weapons. This is especially

* true when it comes to efforts to force Tran to com-

ply with the npr. The insistence on a more aggres-

sive and equitable enforcement of nonproliferation

norms seems certain to cast greater light on what

Israel’ leaders and their American allies have pre-

ferred to keep in the dark.

THE MAKING OF THE TABOO

When President-elect John Kennedy met with

President Dwight Eisenhower on January 19, 1961,

on the eve of the new president’ inauguration, one

of Kennedy's first questions was who would be the

next nuclear proliferators. “Israel and India,” Secre-

tary of State Christian Herter quickly replied. By Jan-

uary 1961 Israel was the most pressing proliferation

problem, Only a few weeks earlier the Eisenhower

administration had established, with a sense of dis-

may and complete surprise, that for nearly three

years Israel had been secretly building a major

nuclear facility near the town of Dimona in the

Negev Desert. It was believed that Israel—if not

stopped by the United States—could become a

nuclear power within a decade or even less.

In fact, the notion that Istael should explore the

nuclear vision was as old as the state itself. David

Ben Gurion, Israel’ first prime minister, had been

obsessed by the nuclear option as the answer to

Israel's security predicament since the days of the

‘War of Independence. He believed that only tech-

nology could provide the qualitative strategic edge

required to overcome Israel's inferiority in popula-

tion, resources, and space. As former Prime Minis-

ter Shimon Peres once put it, “Ben Gurion believed

that science could compensate us for what Nature

has denied us.” This phrase reflects, in essence, the

whole philosophy of Israel’s nuclear project.

From the outset American policy makers viewed

Israel as a special case of nuclear proliferation. By

1961, just about 15 years after a third of the Jewish

people had perished in the Holocaust, and at a time

‘when there were no international nonproliferation

norms, probably no other nation had a stronger

(that is, more justifiable) case for pursuing the

nuclear option than Israel. From the Us perspective,

it was a case of a small and friendly state outside the

boundaries of American alliances and containment

policy, a state that was surrounded by much larger

enemies publicly vowing to destroy it. Unlike China

or India, Israel did not aspire to the status ofa great

power. Most significantly, Israel enjoyed unique

domestic support in America. Kennedy knew very

well that without the votes of about 80 percent of

the Jewish voters in the United States, he would not

have been elected,

Yet, despite allthis, President Kennedy was deter-

mined to thwart Israel's nuclear quest. Kennedy's

“private nightmare” (in the words of Glenn Seaborg,

the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission

under Kennedy) was global nuclear anarchy, a world

of some 20 to 30 nuclear weapon states, Without

decisive international action to curb nuclear prolif-

eration, Kennedy feared this nightmare would

become a reality within a decade or two. And for

Kennedy, Israel was at

Israel's Bomb Revisited * 171

old while promising the Johnson administration

that it would “not be the first to introduce nuclear

‘weapons to the region.” When cia director Richard

Helms finally told Johnson that Israel had crossed

the nuclear divide, Johnson ordered Helms “to keep

this a secret and not to share it even with Rusk and

MacNamara” (the secretaries of state and defense).

The sacred taboo came into being.

THE OPACITY STRATEGY

This taboo, as such, was rooted in history. It was

the unique historical fabric under which Israel went

nuclear in the 1960s—with full technological vigor

but with a great deal of political ambivalence and

caution—and the hesitant American response to it

that gave rise to the taboo. The us effort to stop

Israel's emergence as the worlds sixth nuclear nation

was equally ambivalent at heart and self-deceptive

in action. In retrospect, Israel's nuclear project was

caught in the middle

the center of the battle

against nuclear prolif-

eration. The case of

Israel, he believed, was

where the new nonpro-

Almost 40 years after Israel became a nuclear

weapon state, the nonproliferation regime

remains unable to deal with the Israeli reality.

as the global rules of

the game were fast

changing.

In response Israel

“invented” its unique

liferation norm should

begin. Israel was per-

ceived as the dividing line between the old and irre-

versible nuclear proliferation of the past and the new

nonproliferation prohibition of the future. If the

United States could not influence small Israel not to

go nuclear, how could it persuade the Germans to

give up their own nuclear ambitions? And if the

United States could not stop the Germans, how

could it expect the Soviet Union to prevent China

from gaining the bomb?

These considerations set the stage in the spring

and summer of 1963 for probably the harshest

American-Israeli confrontation, Kennedy threat-

ened Prime Ministers Ben Gurion and Eshkol that

the Us commitment to Israel’ security and well-

being “would be seriously jeopardized” if his

nuclear demands—in the form of American bi-

annual inspection visits at Dimona—were not com-

plied with. At the end of the confrontation, Prime

Minister Eshkol seemed to accept Kennedy's

demands, or so Kennedy was led to believe.

In reality, this did not happen. It was up to Pres-

ident Lyndon Johnson to implement the deal, but

Johnson was initially less principled on the matter

of nonproliferation in general and surely on the

Israeli case in particular. It was during his time in

office that Israel secretly crossed the nuclear thresh-

mode of going (and

then being) nuclear.

Initially, going nuclear opaquely was designed to

limit and ease the collision between Israel and

America nonproliferation policy, as well as to keep

the Arabs (especially Egypt) in the dark. By late

1966, as the NpT was near completion, Israel had

already concluded the research and development

phase for its first nuclear explosive device, but it

dared not to test it. Technologically, Israel could

cross the nuclear threshold, but politically it treated

its nuclear project as an “option.” The Eshkol gov-

ermment avoided making any explicit political deci-

sion. In late May 1967, on the eve of the Six Day

War, Israel secretly assembled two rudimentary

nuclear devices to be readied for the worst-case sce-

narios, but it was cautious not to make use of its

capability even as a deterrent.

More than a year later, Israel informed the United

States that, given its security needs and without

American security guarantees, it could not renounce

its nuclear option and would not sign the NPT. By

September 1969 Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir

had reached a new secret understanding with Pres-

ident Richard Nixon over the nuclear issue. Meir

told Nixon the truth—why Israel had found itself

compelled to develop a nuclear weapons capability

and why it could not sign the weT—but pledged that

172 © CURRENT HISTORY * April 2005

Israel would not become a declared nuclear power.

‘That meant then that Israel would not test, would

not declare itself a nuclear weapon state, and would

ot use its nuclear capability for diplomatic gains,

but rather would keep its bomb in the basement as

a last resort. Israel would not join the NPr, but it,’

would not defy it either. By July 1970 The New York’

Times made public that the us intelligence commu

nity considered Israel a nuclear weapon state.”

Israels nuclear history in the period from 1973 to

the present can be narrated along two distinct and

schizophrenic themes: political caution and techno-

logical resolve. During this period Israel’ policy of

nuclear opacity was transformed from a short-lived

improvisation to a semi-permanent strategic posture.

Over this period, Israeli defense strategists came to

view the policy as a great strategic success because

it provided Israel all the benefits of existential

nuclear deterrence but at a very low political cost.

Nuclear opacity became an indispensable pillar in

the nation’s national security doctrine.

POLITICAL CAUTION

On the side of political moderation, opacity was

seen as the alternative to open nuclear strategy. In

this respect, the 1973 Yom Kippur War had an

important nuclear dimension, although its full

drama has not yet been told. It has been widely

rumored that during the early phase of the war

Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan readied the

nuclear weapons infrastructure, apparently propos-

ing to Prime Minister Meir to arm the weapons in

case Israel came to reach the point of “last resort.”

But Meir refused to concede to Dayan’s worst-case

thinking. American intelligence picked up signs

that Israel put its nuclear-capable Jericho missiles

on a high alert (apparently in a way that was

designed to be noticed). But by Meir’s decision to

resist Dayan’ advice, Israel’ policy of nuclear opac-

ity survived. The prime minister's reluctance to slip

into the nuclear brink made Israel a responsible and

trusted nuclear custodian. This, too, has become an

important legacy.

In the period immediately after the 1973 war there

were significant voices in Israel, including Dayan’,

that argued it was time for Israel to move to an open

nuclear posture. Some of those voices openly rec-

ommended that Israel develop and deploy tactical

nuclear weapons. But in the mid-1970s Prime Min-

ister Yitzhak Rabin (along with his foreign minister,

Yigal Allon) vehemently opposed the introduction of

“magic weapons” (as he publicly referred to them)

and the move into an open nuclear strategy. Rabin

feared the nucleatization of the Arab-Israeli conflict

and was committed to preventing—or postponing —

such a development. The policy of nuclear opacity

‘was for him a matter of political responsibility

Nuclear opacity also allowed Israel to advocate

internationally the idea of establishing a Nuclear

Weapons Free Zone (Nw) in the Middle East. In

1975, as the Israeli government resisted pressure to

join the Npr, Rabin authorized Foreign Minister

Allon to announce at the UN that Israel would sup-

port consultation among all the region's states

toward the establishment of a Nwrz. For the first

time Israel supported the principle of a nwrz with-

out conditioning it with demands for conventional

arms control

Everyone recognized, of course, that this vision

was unrealistic in the absence of regional peace. It

nevertheless clearly demonstrated the Rabin gov-

ernment resistance to adopting proposals in favor

of open nuclear deterrence. Ever since, in one

diplomatic formula or another, Israel has remained

loyal to its principal support for the creation of a

Nwr7 in the region. In the past decade the idea of a

Nwez has been extended to a Weapons of Mass

Destruction Free Zone, at least in principle.

EXPANDED CAPABILITY

On the side of technological resolve, opacity was

instrumental in setting up a friendly environment

that allowed Israel to continue uninterrupted with

its nuclear activities. The decade after the 1973 war

marked an era of rapid technological development

as Istael took full advantage of its freedom of action

under opacity. It is widely believed that during this

period Istael’s nuclear arsenal underwent a major

transformation. By the time of the 1991 Gulf War,

Israel had expanded and modernized its weapons far

beyond the early arsenal of a dozen or so low-yield

first-generation bombs,

But even as Israel significantly upgraded its

nuclear capability in the period between the Yom

Kippur War and the first Gulf War, it did not move

to establish a secured, second-strike capability: While

occasional discussions of the subject took place,

operational and costly decisions were deferred. The

underlying assumption guiding Israeli strategic

planning in this period was that Israel regional

nuclear monopoly was still holding: if and when the

situation shifted, Israel would have ample time to

adjust. The June 1981 bombing of Iraqs Osirak

nuclear reactor was in line with this thinking. Prime

Minister Menachem Begin’s decision to attack the

Iraqi site was a warning to Arab regimes that Israel

would not allow a hostile power a nuclear weapons

capability. It was also a sign that Israel was commit-

ted to continuing its regional nuclear capability.

This has changed since the 1991 Gulf War. Before

the war Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir pushed the

conduct of nuclear opacity to its limits when he

threatened Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein with an

“awesome and terrible” response if Iraq attacked

Israel with weapons of mass destruction (WMD). US

Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney enhanced and

explicated that threat when he openly referred to the

possibility that Israel would use its nuclear capabil-

ity if Iraq dared to launch chemical ot biological

weapons at Israel. By the war's end, some 40 Iraqi

Scud missiles carrying conventional watheads had

been fired at Israel, most of them aimed at Israel's

population centers. That Iraq did not launch a chem-

ical or biological attack on

Israel led Israelis to believe

that the veiled nuclear

deterrent was effective in

blocking Saddam’ use of

nonconventional weapons.

combined with new strate-

gic developments, led to Israel’s decision to estab-

lish a new sea-based strategic arm. By July 2000

Israel completed taking delivery of three Dolphin-

class submarines it ordered from Germany after the

Gulf War, Today it is believed that Israel is on its

way toward restructuring its nuclear forces into a

triad form—with potential delivery by aircraft, mis-

sile, or submarine—assuring the capability to retal-

iate if hit first with was

There is tension between the commitments to

political caution and technological resolve. Only the

policy of opacity keeps this tension hidden.

THE BOMB’S FREE RIDE

In Israel itself, the Israeli nuclear complex

remains a bubble of secrecy that stands as an

anomaly against contemporary norms of proper

democratic conduct—that is, measures of demo-

cratic transparency, accountability, oversight, and

the public right to know. However, Israelis have

learned to live well with this undemocratic taboo.

They have internalized and socialized the taboo; it

has become embedded in the nation’s culture of

national security. The public at large respects the

nuclear taboo and has little desire to tamper with

it, while insiders—the “guardians” of the bubble—

are comfortable with a situation that leaves them

uninterrupted and undisturbed by the citizenry or

Nobody—in or out of Israel—cares to ask

Israeli leaders uncomfortable questions

about the nation’s nuclear status.

Lessons from that war,

Israel's Bomb Revisited © 173

its elected representatives. Those few who are

aware of the undemocratic character of the policy

of nuclear opacity consider it necessary and

unavoidable. From a national security perspective,

they see no alternative

Two fundamental presumptions are involved in

this reasoning. First, there is a consensus among

Israelis that their country’s national security

requires nuclear weapons—that Israel must main-

tain existential deterrence. Under no conceivable

circumstances could Israel afford to rid itself of

this deterrent, not even after the establishment of

regional peace. Recognizing the strength of this

view among the citizenry, one must concede that,

it is inconceivable for any Israeli government

to take public steps that would imply, even only

symbolically, a weakening of Israel’s nuclear

capabilities and strategic

assets

Second, there is a deeply

held conviction that the

international community

would never grant a seal of

legitimacy to Israels nuclear

status. From the perspec-

tive of Israel national security culture, itis doubtful

that even the United States could openly accept Israel

as a legitimate nuclear weapon state, As for Israels

neighbors, it is clear the Arab states would also never

openly accept an Israeli nuclear monopoly. Hence, if

Israel were to put its nuclear assets on the table, the

argument goes, it would find itself on a dangerous

slippery slope that would lead only to new demands

to weaken its nuclear capability. Even limited

acknowledgement and transparency would seem—

in the eyes of the Israeli national security elite—an

irresponsible act.

On the other hand, the argument continues, the

policy of nuclear opacity provides Israel with all of

the benefits of existential deterrence (like those

enjoyed by the declared nuclear weapon states) with-

out any risks, Other regimes in the region can more

successfully avoid domestic pressure to develop their

own Wp if Israel’ status remains opaque. And as

long as the United States continues to shield Israel's

nuclear exceptionalism, Israel can take advantage of

the utility of nuclear deterrence without paying the

dues. Specifically, Israel enjoys all the benefits of the

international nonproliferation regime without accept-

ing any of its obligations for international inspections

and other forms of transparency. Opacity looks to

Israck strategists like the best ofall possible worlds

So why should Israel change anything? The nuclear

posture may be anachronistic and odd, but it is work-

ing well for Israel’ national security.

‘WHAT IS THE ALTERNATIVE?

From the perspective of the international non-

proliferation regime, Israels exceptionalism is surely

a problem. It leaves the Israeli case a constant sore

point, a reminder of the regime’ lack of universality

Israel benefits from the nonproliferation regime—

for example, from the diplomatic efforts to halt

Iran’s nuclear ambitions, which are only possible

because Iran is a signatory to the NPT—without

incurring any responsibilities. And yet, almost 40

years after Israel became a nuclear weapon state, the

nonproliferation regime remains unable to deal with

the Israeli reality.

This inadequacy is not without reason. It is the

legal and political fabric of the NPT bargain itself that

makes the Israeli nuclear case so difficult to cope

with. Legally, the NPT established a baseline, January

1, 1967, for the divide between the nuclear weapon

states and the nonnuclear weapon states under the

treaty, From a technological perspective, by that date

Istael could have tested and declared itself a nuclear

‘weapon state, but politically it chose not to. Conse-

quently, as a matter of legal definition, the NPr can-

not accommodate, let alone legitimize, Israel's

nuclear status, Since Israel presumably did not test

before January 1, 1967, it cannot be accepted into

the NPT bargain as a nuclear weapon state.

The legal-formal problem highlights the real

problem, which is a political one, The very idea of

the Npr was to limit the number of declared nuclear

weapon states—at least to keep the number no

higher than it was on January 1, 1967—and surely

not to legitimize additional nuclear states. From the

perspective of the nonproliferation regime there is,

no political interest in adding new nuclear states, to

put it mildly. The issue is not Israel per se, the argu-

‘ment goes: itis the integrity of the Ner norm.

If this is the case, Israel has not much choice but

to continue its policy of nuclear opacity: This is not

only an Israeli interest—it is the only way the NPT

regime can live with a nuclear-armed Istael. At the

end of the day, a continuation of the status quo is

the only way the international community seems to

cope with the reality of a nuclear Israel. Israel's

nuclear conduct may be undemocratic and

anachronistic, but it is robust and functional, and

not only for Israel, but also for the maintenance of

international nonproliferation norms. Most impor-

tant, despite its deficiencies, it is hard to propose

alternatives to it

BEYOND THE STATUS QUO

Is there a way out of the status quo? Is there a

better way—for Israel itself as well as for the inter-

national community—to deal with the reality of a

nuclear Israel?

While all concede that Israel’s nuclear status is a

problem, conventional wisdom within and outside

of Israel supports the status quo because it sees no

way out of the dilemma, no leeway for reform. As

long as Israel remains committed to retaining its

existential nuclear deterrence, and as long as the

international community has no interest in openly

acknowledging this reality, it is impossible to reform

the status quo. Any change, from either perspective,

s viewed as threatening a delicate balance, pote!

tially causing more harm than good. Israel is not

willing to be more transparent because it fears the

danger of a slippery slope. The international com-

munity is not willing to grandfather Israels nuclear

status because it fears undermining the nonprolif-

eration norm.

This author, against the conventional wisdom,

views the status quo not only as anachronistic but

also burdensome. A mature nuclear program that

functions within a bubble of secrecy exempted from

the scrutiny of Israeli democracy is not a badge of

honor for Israeli democracy, or for Israeli national

security: A state that remains exempt with respect to

the nonproliferation regime—even if it tacitly com-

plies with much of the regime’ obligations—is not

a mark of health for the universality of the regime

On both sides of the problem, the status quo leaves

too much opacity, and too litle transparency.

If reform is possible at all on the Israeli nuclear

case, it must be executed along a general formula

of acknowledgement in return for transparency

and constraints. This formula should apply to

both aspects of the problem, domestic and inter-

national. Domestic acknowledgment (say, by

enacting a law) is probably a precondition for

Israel to receive some measure of international

acknowledgement. The international community

in turn would accept Israel's nuclear status while

demanding limits and accountability.

Acknowledgment is not equivalent to granting

lasting legitimacy to nuclear weapons. Nor is it an

end to the long-term ideal of establishing a

Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone in the

laraels Bomb Revisited © 175

Middle East, as part of the effort to promote lasting

peace among the region's nations. Just as the NPT

itself does not legitimize nuclear weapons—in fact,

it calls for cessation of the nuclear arms race and

nuclear disarmament—so this proposal does not

aim to legitimize the existence of a permanent

Israeli nuclear arsenal,

“WHAT ABOUT ISRAEL?”

It would be good for Israel to come clean on the

nuclear issue, but this can be done, if at all, only if

the international community and the nonprolifera-

tion regime were willing to accept a nuclear Israel

One way to conceive the international aspect of

this—recognizing that amendment of the NPT is a

political impossibility—would be through efforts to

ban the production of fissile material and to apply

this ban to all three de facto established nuclear

weapons states—Israel, as well as India and Pak-

istan (perhaps even along with Iran). This could be

accomplished by a series of unilateral and regional

arrangements, to be complemented perhaps with a

freestanding separate agreement or protocol

As Thomas Graham and I have noted, such a pro-

tocol could permit Israel (along with India and Pak-

istan) to retain their nuclear weapons programs, each

under a different modality, but inhibit further devel-

opment. The protocol could also contain provisions

such as requiring cooperation with the international

nuclear export control system and prohibiting the

explosive testing of nuclear devices, as well as other

provisions either in the Ner or associated with it. As

a result of these commitments, Israel (as well as India

and Pakistan) would have a settlement of the nuclear

issue with the world community and an acknow!-

edgement of its status through association with the

nonproliferation regime. India, Israel, and Pakistan

could sign the protocol, as well as the NPT Depositary

States, which since the 1960s have been considered

the general managers of the NPT regime.

The time has come to address the nuclear case of

Israel, along with the two other de facto nuclear

states, in a realistic and honest fashion. While the

nonproliferation regime should acknowledge Israels

nuclear status, that country in return would have

to accept new and explicit nonproliferation com-

mitments—a fair bargain given Israel’ stake in pre-

venting the further spread of nuclear weapons. i

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- A Description of Early Maps, Originals and Facsimiles (1452-1611) by E. L. Stevenson (1921)Document126 paginiA Description of Early Maps, Originals and Facsimiles (1452-1611) by E. L. Stevenson (1921)Luciano Dondero100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- A Guide To Historical Cartography A Selected, Annotated List of References On The History of Maps and Map Making by W. W. Ristow (1960)Document38 paginiA Guide To Historical Cartography A Selected, Annotated List of References On The History of Maps and Map Making by W. W. Ristow (1960)Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Marx Engels ManifestoDocument22 paginiMarx Engels ManifestoLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- Johann Schöner, Professor of Mathematics at Nuremberg, A Reproduction of His Globe of 1523 (1888)Document16 paginiJohann Schöner, Professor of Mathematics at Nuremberg, A Reproduction of His Globe of 1523 (1888)Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Philosophy of LanguageDocument201 paginiPhilosophy of Languageigorljub100% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Atlas Accompanying Rev. C. A. Goodrich's Outlines of Modern Geography ... Map of Asia (1826)Document18 paginiAtlas Accompanying Rev. C. A. Goodrich's Outlines of Modern Geography ... Map of Asia (1826)Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- HypatiaDocument4 paginiHypatiaCorneliu Meciu100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- OWS - Peer-to-Peer Communism vs. The Client-Server Capitalist State' - The Telekommunist ManifestoDocument58 paginiOWS - Peer-to-Peer Communism vs. The Client-Server Capitalist State' - The Telekommunist ManifestoA.J. MacDonald, Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Lunev - Through The Eyes of The EnemyDocument158 paginiLunev - Through The Eyes of The EnemyJohn Smith100% (16)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- Cartography of Rhode Island by H. M. Chapin (1915) PDFDocument24 paginiCartography of Rhode Island by H. M. Chapin (1915) PDFLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rethinking Insurgency PUB790Document77 paginiRethinking Insurgency PUB790Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World On Mercator's Projection, To Illustrate Harpers Gazetteer by J. C. Smith & Son (1855)Document1 paginăThe World On Mercator's Projection, To Illustrate Harpers Gazetteer by J. C. Smith & Son (1855)Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- A Guide To Historical Cartography A Selected, Annotated List of References On The History of Maps and Map Making by W. W. Ristow (1960)Document38 paginiA Guide To Historical Cartography A Selected, Annotated List of References On The History of Maps and Map Making by W. W. Ristow (1960)Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Cartography of Rhode Island by H. M. Chapin (1915) PDFDocument24 paginiCartography of Rhode Island by H. M. Chapin (1915) PDFLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Freedom Flyer 2012Document1 paginăFreedom Flyer 2012Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- A Booke Called The Treasure For Traueilers Deuided Into Fiue Bookes or Partes, Contaynyng Very Necessary Matters, For All Sortes of Trauailers, Eyther by Sea or by Lande by W. Bourne (1578)Document284 paginiA Booke Called The Treasure For Traueilers Deuided Into Fiue Bookes or Partes, Contaynyng Very Necessary Matters, For All Sortes of Trauailers, Eyther by Sea or by Lande by W. Bourne (1578)Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

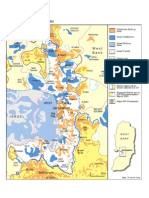

- Sanitation in The West Bank and GazaDocument8 paginiSanitation in The West Bank and GazaLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Comprehensive Atlas, Geographical, Historical & Commercial by T. G. Bradford (1835)Document285 paginiA Comprehensive Atlas, Geographical, Historical & Commercial by T. G. Bradford (1835)Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water in The West Bank and GazaDocument15 paginiWater in The West Bank and GazaLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 1973 Oil CrisisDocument2 paginiThe 1973 Oil CrisisrahulindceÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- 1973 - Nixon Arab Israeli War (2013) PDFDocument62 pagini1973 - Nixon Arab Israeli War (2013) PDFLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- Edgar OballanceDocument174 paginiEdgar OballanceHisham Zayat100% (2)

- Israel and The Middle East - A Study PlanDocument3 paginiIsrael and The Middle East - A Study PlanLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muslim Brotherhood in AmericaDocument52 paginiMuslim Brotherhood in AmericaLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Jabo Tin Sky Pamphlet 201007141Document36 paginiJabo Tin Sky Pamphlet 201007141Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reframing The Enemy After France's 911Document3 paginiReframing The Enemy After France's 911Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1973 October Kramer Re War Museums in Cairo DamascusDocument20 pagini1973 October Kramer Re War Museums in Cairo DamascusLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Projected West Bank Partition Plan 2008Document1 paginăProjected West Bank Partition Plan 2008Luciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Fortress JerusalemDocument1 paginăFortress JerusalemLuciano DonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)