Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Jam Langlois

Încărcat de

Nanda Win LwinDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Jam Langlois

Încărcat de

Nanda Win LwinDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Airport attacks: The critical role

airports can play in combatting

terrorism

Received (in revised form): 6th April, 2017

JACQUES DUCHESNEAU

is Senior Advisor, Civil Aviation Security and Aviation Terrorism at Aviation Strategies International. He has served

as Member of Parliament in the Québec National Assembly, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Canadian

Air Transport Security Authority and Montreal’s Police Chief. Dr Duchesneau has been bestowed with the Order of

Canada, the National Order of Québec and France’s National Order of Merit. He holds a PhD in War Studies from

the Royal Military College of Canada.

MAXIME LANGLOIS

is Director, Corporate Services at Aviation Strategies International. He previously worked for INTERPOL, the

Jacques Duchesneau

United Nations and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade of Canada.

Abstract

This paper uses a unique database of aviation terrorist attacks to analyse the phenomenon of

airport attacks. The evolution of aviation terrorism is described with a particular focus on airport

attacks, using empirical and historical data to form a factual baseline for historical analysis and

policy recommendations. The authors make a distinction between acts of unlawful interference, the

all-encompassing term the International Civil Aviation Organization uses, and actual terrorist attacks

against civil aviation. While statistics demonstrate that airport attacks have been perpetrated steadily

since the 1970s, with no major fluctuations in recent years, they also demonstrate that airport attacks

Maxime Langlois

may have the potential to become more lethal than ever before. Analyses and guidance are also

provided on how to better protect airports, suggesting that the hardening of aircraft as targets has

actually transferred considerable security risk to airports. To effectively secure the air transportation

system, a three-pronged approach to aviation security is proposed, transcending airport security and

reaching far beyond aviation in its scope.

Keywords

airport, aviation, security, terrorism

Jacques Duchesneau,

Aviation Strategies International,

440 René-Levesque Blvd West, INTRODUCTION the gradual addition of enhanced security

Suite 1202, Montréal, QC,

Canada H2Z 1V7 Since the dawn of commercial aviation, measures, airports by nature have had

Tel: +1.514.398.0909; terrorists have used the air transportation to remain public areas, at least partly

E-mail: duchesj@mac.com

system to both commit their attacks and accessible to anyone, hence making them

to attack the system as a target in its own preferred targets.

Maxime Langlois,

Aviation Strategies International, right. Airports in particular have stood Airport attacks, along with aircraft

440 René-Levesque Blvd West,

Suite 1202, Montréal, QC, out as relatively ‘soft’ targets for terrorist attacks, belong to a specific aviation ter-

Canada H2Z 1V7

attacks. While aircraft have been hard- rorism modus operandi (MO, ie method

Tel: +1.514.398.0909;

E-mail: max.langlois@icloud.com ened as targets over recent decades with of attack) called ground attacks, which

342 Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Airport attacks: The critical role airports can play in combatting terrorism

have in effect been alternatives to other countermeasures to better protect the

MOs including hijacking, sabotage and system and reduce the number of successful

suicide missions. Airport and aircraft attacks terrorist attacks against the sector. The

are very distinctive by their nature, but academic and professional literature reveals

often mixed and hard to differentiate given seven fundamental reasons explaining why

they have commonly occurred at airports. terrorists have targeted civil aviation.

While launched from the ground, aircraft Namely, such attacks:

attacks specifically target aircraft, whether

they are gated, taxiing, taking off, landing 1. project a global reach, even if local;

or cruising. Such acts have been conducted 2. generate the rapid transmission of

using guns, grenades, rocket-propelled information, increasing audience and

grenades (RPGs), man-portable-surface impact;

to-air-missiles (MANPADS) and other 3. depreciate the embodiment of state power

weapons. Airport attacks are acts in which that airlines and airports symbolise;

individuals or installations on airport 4. lead to powerful economic consequences

grounds are violently and specifically beyond civil aviation;

targeted. Targets can include terminals, 5. have a high lethal potential, and a high

check-in counters, boarding gates, passen- probability of affecting nationals of

ger areas, vehicles, parking lots and other several countries;

equipment or buildings, but excluding 6. impede interconnectivity, disrupting global

aircraft themselves. air transport; and

Terrorist attacks committed against 7. provide the capacity to instantly make a

airports in 2016, namely in Brussels and powerful statement to world leaders.2,3

Istanbul, have stirred the debate about

airport security and what can and should In his doctoral thesis,4 one of the authors

be done to prevent this type of attack. crosschecked the evolution of aviation

The principles addressed in this paper are terrorism against changes made to the

based on research material that includes international aviation legal and regulatory

a unique database of aviation terrorist framework. The research revealed that

attacks recently developed for a doctoral civil aviation conventions and protocols

thesis. The paper describes the evolution created specifically to disrupt particular

of aviation terrorism with a particular aviation terrorism MOs have had mixed

focus on airport attacks, sets out facts results. Nevertheless, the cumulative impact

using empirical data and offers guidance of international conventions and protocols

on how to protect airports. seems to have ultimately created an overall

deterrent effect resulting in a decline in

aviation terrorism, especially noticeable

AVIATION TERRORISM as of the early 2000s. In order to answer

Aviation terrorism can be defined as a politi- the aforementioned thesis’ research ques-

cal act against civil aviation carried out by tion, extensive research was conducted to

non-state actors who systematically target gather in a single database every act of

civilians and intentionally use violence unlawful interference having been per-

in order to create terror and coerce petrated against civil aviation between

authorities, at times by making demands.1 1931 and 2016.5 All acts were subsequently

Understanding why terrorists have tar- categorised by MO: ground attack,

geted civil aviation is crucial to devising hijacking, sabotage and suicide mission.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017 343

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Duchesneau and Langlois

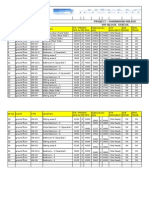

Table 1 summarises the composition that the 6,184 deaths from aviation ter-

of the database per MO,6 along with rorism have occurred in only 175 attacks

the number of corresponding deaths. (28 per cent) meaning that the other 460

There is a direct and consistent correla- attacks (72 per cent) caused no casualties.

tion between MOs and their respective For its part, Figure 1 illustrates the

number of deaths; the most used MOs evolution of the aviation terrorism MOs

have been the least lethal, and vice versa. for the 1960–2016 period. The 1931–1959

Another important category of the period is purposely excluded, given the

database was motive, precisely created to extremely low prevalence of aviation

distinguish actual terrorist attacks from terrorism before 1960, to concentrate

mere criminal incidents, based on the on patterns of MOs occurring over the

aforementioned def inition of aviation past 57 years. The graphic clearly shows

terrorism. Out of all 2,071 listed acts of that ground attacks and hijackings have

unlawful interference, only 635 could been the MOs of preference for aviation

be definitively categorised as terrorist.7 terrorists. It also shows that the hijack-

Table 2 provides statistics on the MOs ings, sabotage and suicide missions have

used to carry out those 635 terrorist sharply declined to negligible levels since

attacks as well as their consequent fatal- the 9/11 attacks; however, the number

ities. The same pattern applies here: the of ground attacks has not followed the

most widely used MOs have been the same trend and continues to f luctuate on

least lethal, and vice versa. The comparison a pre-2000s pattern.

of Tables 1 and 2 reveals that whereas a

minority of acts of unlawful interference

have been terrorist attacks (31 per cent), AIRPORT ATTACKS

a large majority of total deaths are attrib- Perpetrators have used the full range of

utable to terrorist attacks (72 per cent). possibilities to attack airports, from mass

Furthermore, it is important to mention killings using grenades and automatic

Table 1 Unlawful interference statistics, 1931–2016

Acts of unlawful interference

Ground attack Hijacking Sabotage Suicide mission Total

536 1,308 174 53 2,071

Deaths from acts of unlawful interference

Ground attack Hijacking Sabotage Suicide mission Total

1,865 814 2,829 4,000 9,508

Table 2 Terrorist attacks statistics, 1931–2016

Terrorist attacks

Ground attack Hijacking Sabotage Suicide mission Total

338 221 56 20 635

Deaths from terrorist attacks

Ground attack Hijacking Sabotage Suicide mission Total

1,650 279 1,726 3,159 6,814

344 Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Airport attacks: The critical role airports can play in combatting terrorism

25

20

15

Attacks

10

0

1960

1962

1964

1966

1968

1970

1972

1974

1976

1978

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

Ground Attacks Hijacking Sabotage Suicide Mission

Figure 1 Evolution of aviation terrorism MOs

weapons to small homemade bombs lethal’ trend identified in the previous

exploding in parking lot garbage bins section.9

without injuring anyone. Attacking an Contrary to some current popular

airport is generally viewed as a substitute beliefs, airport attacks are not a new trend.

for attacks on airliners—a ‘‘poor’s man’s’’ The MO goes back to the early 1970s

hijacking, a simpler way to make a political and was first used by Palestinian groups.

point without running the risks.8 Attacks The first terrorist airport attack listed in

against check-in counters and offices can the database occurred on 10th February,

be considered symbolic attacks indicating 1970 at Munich Airport, Germany. One

which specific aircraft or countries ter- Egyptian and two Jordanians affiliated

rorists would attack if security measures with the Popular Front for the Liberation

protecting airliners were less stringent. of Palestine (PFLP) attacked a bus carry-

For the purpose of this paper, the ing El Al passengers to their aircraft with

authors have isolated airport from aircraft guns and grenades, killing one and injur-

attacks in the aviation terrorism database ing 11.10 Through its ‘general command’

for analytical purposes. Table 3 reveals cluster, the PFLP was extremely active

that terrorists have targeted airports 232 in aviation terrorism from the late 1960s

times between 1931 and 2016, that is 37 to the late 1970s. Many authors attribute

per cent of all terrorist attacks, causing a the emergence of both international and

total of 468 deaths, or 7 per cent of all aviation terrorism to the PFLP, whose

deaths from terrorist attacks. This trend operatives proved particularly capable at

is consistent with the ‘most used but least hijacking commercial airliners carrying

Israelis. Their objectives were to blackmail

the government of Israel, namely for the

Table 3 Terrorist airport attacks, 1931–2016

release of Palestinian prisoners, and to

Number % of all terrorist attacks internationalise the Palestinian cause.

of acts 232 37% On 8th May, 1972, PFLP operatives

# of deaths 468 7%

hijacked a Sabena Airlines f light, landing

Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017 345

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Duchesneau and Langlois

it at Lod Airport near Tel Aviv. Refusing On 30th May, 1972, the PFLP delegated

to be blackmailed once again, the Israeli a three-member JRA cell to retaliate for

government mandated elite commandos the Israelis’ surprise move of three weeks

to storm the airplane and release the pas- before and carry out the first full-scale

sengers. The operation was successful: two airport attack in history. The JRA oper-

hijackers were killed and the other two atives f lew on Air France to Lod Airport.

captured. One passenger died and five While about 250 passengers were waiting

others were injured, but the government at immigration, the terrorists pulled out

of Israel made the point that it would automatic weapons and hand grenades

not be blackmailed through aviation ter- from their carry-on luggage and fired at

rorism anymore. This was a watershed the crowd. Their attack killed 28 people

moment for nascent aviation terrorism, the and injured about 70 others.12 The Lod

very first time a government launched a Airport attack shares several character-

security operation to abort an act of istics with tens of other airport attacks,

unlawful interference while accepting including the fact that people waiting in

the risk of collateral damage. It was also a line to be ‘processed’ allowed terrorists

watershed moment for airport attacks; the to maximise the carnage of their attacks.

PFLP, which had mostly refrained from Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of

killing civilians in its past operations, did terrorist airport attacks and their related

not anticipate the Israeli government’s deaths from 1970 to 2016. Except for

surprise move. 1983 (11) and 1992 (16), the number of

As a Marxist group, the PLFP maintained terrorist airport attacks has consistently

relations with several foreign revolutionary f luctuated between 0 and 10 per year.

groups such as the Japanese Red Army As for the number of deaths, it has oscil-

( JRA) and the Irish Republican Army.11 lated based on the number and success of

Figure 2 Evolution of terrorist airport attacks

346 Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Airport attacks: The critical role airports can play in combatting terrorism

airport attacks. Peaks are noticeable in 1972 levels. The provisions of Annex 17 and

(corresponding to the Lod Airport attack), its amendments can be categorised in

between 1984 and 1986, between 2000 five different groups: (1) general principles,

and 2003, and between 2014 and 2016. organisation and administration; (2) airport

The 1984–1986 peak is in part attrib- operations; (3) aircraft operations; (4) air-

utable13 to a coordinated airport attack craft in the air; and (5) international

by Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) on cooperation.

27th December, 1985. First, four armed The most visible and tangible aviation

men attacked the El Al and Trans World security measures are deployed at airports.

Airlines check-in counters at the Rome ICAO’s Annex 17 lists the roles and respon-

Airport, firing guns and throwing grenades sibilities of airport operators regarding

at a long queue of passengers. The ter- screening operations, prevention activities

rorists managed to kill 16 and wounded and activities in a rapid response to attacks.

99 before the police killed three of them. Airport operators are responsible for the

Moments later, three terrorists stormed coordination of agencies involved in

the Vienna Airport and threw grenades aviation security. The senior airport

at passengers queuing up at the El Al security personnel also lead the Airport

counter, killing three and injuring 40. Security Programme (ASP), the airport

As St. John points out, these attacks were security committee and prevention

excellent demonstrations of the vulnerability campaigns. It is also responsible for the

of airport terminals.14 The 2001–2003 peak development and implementation of

is for its part largely explained by airport emergency plans. ICAO member states

attacks carried out in Sri Lanka by the must have authorised officials deployed

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. The at international airports to assist and deal

graph also shows that 2016 was the most with suspected or actual situations of

lethal year for terrorist airport attacks unlawful interference with civil aviation.16

so far, with 60 deaths, entirely attributable Annex 17 also requires that airport

to attacks conducted at Brussels Airport on administrations ensure additional security

22nd March (15 deaths) and at Atatürk measures for specific f lights upon request

Airport in Istanbul on 28th June (45 deaths). from other states.17 Airport design and the

infrastructure plan of the airport are also

key components in the efficiency of

PROTECTING AIRPORTS security systems.

The framework In reality, this translates into the ASP

Introduced in 1974, Annex 1715 to the seeking to achieve the following core

International Civil Aviation Organization’s security tasks: (1) the pre-board screening

(ICAO) Chicago Convention was intended (PBS) of travellers and their carry-on

to establish an evolutionary framework baggage; (2) the hold-baggage screening

for a multilayered aviation security system (HBS); (3) the screening of employees

that would form a defensive structure to and crew, also known as non-passenger

deter, prevent and respond to various screening (NPS); (4) the control of access

threats. Such a multilayered approach to the restricted areas through the guide-

also improved the chances of intercepting lines of the airport perimeter security

a threat at the different stages of an ongoing programme, which is complemented by

attack. For example, a threat undetected the airport perimeter intrusion detection

at level 1 should be detected in succeeding system (PIDS); and (5) the supply chain

Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017 347

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Duchesneau and Langlois

and screening systems for cargo and mail. the air on the ground inevitably increases

Trained officers, whose qualifications are the vulnerability of airports and makes

regularly tested, perform all these activities. them attractive aviation targets. The use

The boundary between a restricted area of early warning systems giving security

and a non-restricted area (landside area) teams sufficient time to activate check-

of an aerodrome is divided by a primary points on airport access roads, shut down

security line. The landside area is where terminals and block entrance areas to

both travelling passengers and the non- stop attackers are but just a few ideas to

travelling public have unrestricted access enhance security at airports. The addition

(eg public areas, parking lots and roads). of bulletproof windows to protect people

The objective of any security system inside the terminal and delay entry to

is to delay or deter the forceful entry of terrorists, designated high-protection areas

intruders into a protected area to allow where passengers and employees could take

time for reinforcement units to come to refuge rapidly during an active shooter

the rescue. In the specific case of airports, situation are also concepts deserving of

the Annex 17 multilayered system aims to exploration.

locate and address weapons or dangerous

devices at the airport, precisely before

they represent any risks to aircraft and ‘Cat and mouse’

their passengers. This hardening of the The terrorism–security conundrum has

aircraft targets creates considerable security evolved into a game of ‘cat and mouse’.

and procedural stress to the airport itself, This applies, but is not unique to, the air

hence the complexity of core security transport system. On the one hand, states

tasks. As security measures hardened the and security experts have continually

protection of passengers and aircraft, reacted to acts of terrorism, coming up

airport terminals and facilities became with new countermeasures, tactics, tools

attractive soft targets for terrorists. Indeed, and processes to stay at least one step

airport attacks are highly valued by ter- ahead of evolving threats. On the other

rorists because, for the most part, they hand, terrorists have continuously sought

need less preparation and sophistication new and innovative ways to get around

than airborne attacks, can cause huge those new security measures while enabling

casualties and damage, and offer greater them to proudly re-invent themselves with

escape options. The statistics presented determination.

in the previous sections tend to demon- While security authorities must address

strate that using airports as ‘filters’ to attacks that have already occurred and

better protect aviation may have indeed make sure they cannot be repeated, they

contributed to a decrease in the number must put more efforts in the anticipation

of terrorist attacks against aircraft. But of the next terrorist innovation and act to

one may not be surprised that airports, secure vulnerabilities before terrorists

as ‘filters’, have not witnessed the same launch a new attack. Unfortunately, this

declining trend in attacks. is very difficult to accomplish, for two

Simply put, the principle that security reasons. First, such attacks are what Taleb

in the air begins with security on the calls ‘Black Swans events’18 in the sense

ground has proven to work; what is less that they are rare, that they have a high

clear is how the regulatory framework impact and that people analysing them often

has adapted to the principle that securing use retrospective predictability ( judging

348 Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Airport attacks: The critical role airports can play in combatting terrorism

an event with the advantage of hindsight). at an airport is an extremely complicated,

Although such terrorist attacks become multifaceted and overwhelming task.

readily explainable after the fact, they are Large numbers of people, laden with

exceedingly difficult for security author- baggage and preoccupied with their own

ities to imagine ahead of time, which in agendas, are concentrated in relatively

turn makes it extremely challenging to small areas. Airports are generally left wide

anticipate, prevent and thwart. Second, open to all who wish to enter, presenting

potential terrorists are not unref lective potential suicide bombers with the oppor-

actors whose actions can be readily calcu- tunity to blow up their explosives inside

lated, but are rather rational, resourceful terminals. As mentioned in a 2004 RAND

and often ingenious human beings who study, the fact that matters the most is ‘not

are highly motivated to find any and every the size of the bomb—it’s where it’s deto-

point of weakness in security and exploit nated.’19 One may argue that a passenger

it. Terrorists, like security authorities, are waiting in line to be processed at check-in,

motivated to anticipate and outwit their security or boarding is a ‘sitting duck’.

opponent, but they do have the upper The current screening checkpoints

hand in the ‘cat and mouse’ scheme. system is characterised by four funda-

In summary, it is utterly necessary, mentals facets, each well-intentioned but

but not sufficient, for security authorities deeply f lawed. First, it is focused on

to adapt their behaviour and measures the detection of prohibited items; this is

based on past terrorist attacks. The current resource-intensive, akin to trying to find

terrorist context demands this adaptation a needle in a haystack. Secondly, every

and security authorities must provide it, single passenger is considered as a possible

namely by assessing their performance, threat, even if an extreme majority of

learning lessons and following best practices. travellers do not pose any risk to civil

But this process must be balanced with a aviation. This one-size-fits-all approach is

major anticipation effort, precisely because time-consuming, expensive and inappro-

the real danger lies in placing too much priate. Third, because authorities apply

confidence in long-established security uniform and inflexible standard operating

measures that persistent foes can patiently procedures, they become predictable and

circumvent. In reality, such thinking therefore become vulnerable to terrorist

multiplies the danger factor by prompting exploitation. Finally, as mentioned above,

the illusion of security without actually slow screening checkpoints unintentionally

providing any. The ‘fighting the last war’ create chokepoints, which in themselves

attitude will always result in authorities can represent a target, threatening the

lagging behind terrorists’ tactics and inno- security of passengers.

vation. A change in attitude is central A new system is required and should

because terrorist attacks, both generally be based on the dual concepts of risk-

and against civil aviation, continue to management and randomisation, striving to

occur today and are likely to continue for be both swift and inconspicuous. New

the foreseeable future. technology should be used to enable low-

risk passengers to escape queues and walk

uninterrupted through security without

Standing up to airport attacks having to take anything out of their bags

Given the global nature of the air transpor- and pockets. The main objective should

tation sector, planning adequate security be to focus on high-risk passengers rather

Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017 349

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Duchesneau and Langlois

than concentrating solely on objects. This to effectively prevent future attacks

would ensure that people who could pose against civil aviation, they must be able to

a threat are screened more thoroughly, anticipate a threat and develop a strategy

while low-risk passengers would enjoy to protect the system as a whole, reaching

an improved and expedited travelling far beyond the airport. Such a preventive

experience. Such practice, however, inev- strategy should have three interlocking

itably comes with an implicit but strong elements: (1) intelligence and warning;

‘profiling’ component that, beyond its (2) prevention and deterrence; and (3) crisis

lack of objectivity, is politically and legally management and resilience.

unacceptable in numerous countries, espe-

cially western democracies.

Because of the very systemic nature of Intelligence and warning

air transportation, one must note that such Like terrorism, intelligence is a means to an

security-driven changes would nonetheless end. For a state, this end can be political,

have deep planning and operational impli- commercial or security related. Security

cations reaching far beyond aviation is relative, and therefore the purpose of

security. Existing airport infrastructures intelligence is to attain a relative security

have been planned and designed to meet advantage.21 The role of intelligence is

the current needs and requirements of to help maintain or enhance security by

aviation security. Major changes to the providing early warning of threats in a

existing model would create an immediate manner that allows authorities to imple-

domino effect that would virtually impact ment a preventive policy or strategy in a

all airport stakeholders and functional timely fashion.22 The role of intelligence in

areas, including commercial management, preventing acts of terrorism is complicated

engineering, information technology and by the difficulty in accessing encrypted

safety. Furthermore, even if unilaterally communications channels used by terrorists,

imposed by regulators for the betterment to counter their combat skills developed

of aviation security, such changes would in numerous armed conflicts, and to adapt

come with a hefty price tag, in all prob- constantly and take into account the

ability being passed to passengers and/or evolution of terrorist behaviours. Fur-

tax payers one way or another. thermore, Smelser writes that there are

Many of the world’s largest airports five sources of difficulty for intelligence

are like cities unto themselves, employing analysts trying to pre-empt terrorists:

thousands of people and processing tens (1) terrorists are mobile; (2) they rely on

of millions of passengers on an annual secrecy; (3) they are usually composed

basis. Terrorists are in total command of radical groups; (4) they are recruited

when deciding what, where, when and among kin, friends and neighbours; and

how to attack a target. They will typically (5) the intelligence and security commu-

assess during their planning phase where nities do not always cooperate.23

they will meet with the least security There has been significant progress in

resistance, and they will find ways to cir- the intelligence community since the 9/11

cumvent the remaining defence systems. attacks, that is the day it became evident

As such, countermeasures cannot only con- that no single organisation had all the

sist of a sporadic investment made only in answers; however, preventing terrorist

response to a specific threat or an actual attacks remains a complex and thankless

act of terror.20 If security authorities aim task because its action is not judged by its

350 Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Airport attacks: The critical role airports can play in combatting terrorism

effectiveness, but by its failures, such as over an explosive-laden laptop to a pas-

those identified in the 9/11 Commission senger about to board Daallo Airlines

Report. 24 Therefore, the intelligence Flight 159 in Mogadishu, Somalia. When

community needs to solve those malfunc- the aircraft reached a certain attitude, the

tions by developing stronger partnerships passenger detonated his bomb and was

and obtaining the necessary tools to per- sucked out of the aircraft. The attacker

form properly. Hence, these changes will was the only victim of the attack thanks

enable governments and security author- to the captain, who managed to land the

ities keep pace with terrorist groups which airplane safely.

themselves are often highly motivated and Analysing and understanding threats

tightly coordinated. and vulnerabilities is a process similar to

those used by engineers who are perma-

nently tasked to assess systems’ anomalies

Prevention and deterrence that can potentially lead to failures. Their

Prevention and deterrence are intrinsically analysis and interpretation of results

intertwined. Some defensive measures help constitute an important step leading to

manage real security problems (ie hold- problem solving. For airport security,

baggage screening), while others are more such a systemic approach must include

focused on managing the travelling public’s public area surveillance, identification of

fears and perceptions (eg sporadic police specific threats and vulnerabilities, crowd

presence). Although it is impossible to observation, social media monitoring and

develop a perfect security system seamlessly learning lessons from terrorist attack anal-

in phase with emerging threats and ter- ysis. Because such large areas as airports

rorist innovation, two things are needed cannot be sufficiently covered around the

to prevent and deter airport attacks: clock, multilayered ground surveillance

(1) a comprehensive understanding of radars and other new technologies can

one’s vulnerabilities; and (2) comprehen- detect movement beyond and inside

sive knowledge of opponents and their fence limits and alert personnel to security

capabilities. breaches instantly. Though these systems

Large numbers of ground handlers, are costly and complex, they are required

aircraft cleaners and maintenance per- to offer meaningful security.

sonnel have unrestricted and unlimited In addition to the cumulative effect

access to the airside of airports. Despite of conventions, protocols and security

screening of personnel, each of these measures, the general level of high-alert

individuals potentially has the ability to on which security forces have operated

smuggle weapons and explosive devices since 9/11 has certainly had a deterrent

into the sterile zones of their airport, sab- effect on aviation terrorism. Statistics

otage aircraft by tampering with critical point to a decrease in the number of ter-

f light systems and so on. Furthermore, rorist attacks since 2003, while air traffic

would-be terrorists can deliberately seek has grown at about 5 per cent annually

employment at an airport in order to during the same period.25 After adopting

gain insider access. The whole aviation deterrence as a goal, many best practices

security system is jeopardised if airport can be implemented to maximise their

and airline employees cannot be relied dissuasive effect: for example, increasing

upon. This was the case on 2nd February, police presence to deter attacks, detect-

2016 when two airport employees handed ing suspicious behaviours or immediately

Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017 351

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Duchesneau and Langlois

responding to active shooter situations procedures. For example, if authorities have

to stop the assault. Another suggestion an inf lated perspective of their capacity as

would be to proceed with proactive secu- part of the organisation’s culture, that can

rity questioning of passengers, which is hinder implementation of overall strate-

considered by many experts as a more gies. Introspectiveness allows all parties

effective deterrent than the passive obser- involved in aviation security to evaluate

vation of behaviours. This process should if they eff iciently work at detecting,

always occur in plain view of the public disrupting or containing current and future

to clearly demonstrate security presence as threats to civil aviation. It can also create an

opposed to a subtler manner.26 The main appreciation of the sense of vulnerability

objective of deterrence is to convince among personnel, while giving them a

terrorists that their attack will either be chance to enhance better relationships

pre-empted or trigger a swift response with the travelling public. Such re-

by the authorities, which would then examination also offers a great possibility

underscore the limits to carrying out for authorities to emulate the industry

their plan. leaders’ best practices and learn from

colleagues. Last, but not least, it is most

important that first responders be well

Crisis management and resilience equipped and trained to make terrorist

Terrorist attacks will inevitably continue attacks less damaging, thus indirectly

to happen, and authorities assigned to discouraging them.

protect the travelling public must con- When terrorist attacks are repeated,

stantly be aware of existing threats, devise people ultimately learn to manage their

ways to face the unexpected and learn fear. The travelling public as well as airport

how to cope with uncertainty, day in and employees must then be educated in

day out.27 Guihou and Lagadec contend adapting and controlling their emotions

that the pursuit of ‘zero risk’ that started in the face of terrorism. This is called

during the final stages of the Cold War resilience, a capacity to rebuild psycho-

and abruptly ended on 9/11 is an illusion logically after a severe shock and regain

because risks can never be eradicated.28 fortitude. People and governments should

The authors suggest that the elimination acknowledge that terrorist attacks will

of all potential risks is an unattainable continue to occur occasionally despite

goal and in fact never existed and will strong security mechanisms. A resilient

never exist, especially regarding the ter- attitude is at the intersection of keeping

rorist threat. Consequently, it is fair to say failures low and knowing what to do

that the efforts to reach such a goal would instinctively to keep the security system

not be practical from an aviation security running. This will allow people to cope

perspective. Indeed, it might come with with fear and economic consequences

costly and detrimental trade-offs for the emerging from terrorism. Such an atti-

travelling public while jeopardising respect tude will also help properly balance the

for the rule of law. way government deals with information.

Hardening airport and aircraft targets to As noted by Gregory Treverton: ‘People

prevent terrorist attacks has proven to be an want information, but the challenge for

effective solution; however, experience has government is to warn without terrifying.’29

also shown that facing new threats is The success of aviation security depends

always an impetus to re-evaluate existing not only on laws and regulations, advanced

352 Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Airport attacks: The critical role airports can play in combatting terrorism

technology and effective operations, but and warning, prevention and deterrence,

also on the establishment of a culture of and crisis management and resilience to

security that is ingrained in the public maximise their efforts.

and civil aviation authorities. This con- The desire and potential of terrorists

sideration must be factored into future to attack civil aviation, combined with the

aviation security policies. vulnerabilities of the air transport system

and the ability of terrorist groups to easily

cross borders, represents a continued threat.

CONCLUSION Although progress has been made in disrupt-

The current aviation security framework ing aviation terrorism, the basic features of

was ingeniously designed with multiple civil aviation always make it an attractive

layers, with the main objective of better high profile target for terrorists, meaning

protecting aircraft against acts of unlawful that it is very unlikely they will give

interference. Statistics on aviation terror- up their focus on civil aviation in the

ism tend to demonstrate that this system foreseeable future.

has over time, and especially since the

early 2000s, led to a significant decrease References and Notes

in the number of attacks against aircraft, (1) For more information about this definition

such as hijackings and sabotage. Never- and the various attempts to define aviation

theless, such a decline has not been seen terrorism, see Duchesneau, J. (2015) ‘Aviation

with the incidence of airport attacks; their terrorism: Thwarting high-impact low-

probability attacks’, PhD thesis, Royal

number have continuously f luctuated Military College of Canada, Kingston.

between 1 and 10 a year since the early 1970s, (2) Acharya, D. (2016) ‘Why Islamic State

with no significant and steady decrease target airports: A global stage and variety of

nationalities’, First Post, 4th July 4, available

whatsoever since the early 2000s. Figure 2

at: http://www.firstpost.com/world/foreign-

showed that 2016 was in fact the most passengers-a-global-stage-why-islamic-state-

lethal year for terrorist airport attacks on targets-airports-2871798.html (accessed 15th

record. Although the number of deaths July, 2017).

(3) Azani, E., Atiyas Lvovsky, L. and Haberfield,

from airport attacks since 2011 is still not D. (2016) ‘Trends in aviation terrorism’,

unprecedented (similar ‘waves’ have been Herzliya, IS, International Institute for

seen before), the trend will set a new Counter-Terrorism, August, available at:

precedent if it continues for a few years. http://www.ict.org.il/Article/1757/trends-in-

the-aviation-terrorism-threat (accessed

The fact of the matter is that aviation 11th August, 2016).

security creates considerable security stress (4) Duchesneau, ref. 1 above.

to airports. Protecting the air begins on (5) Seven databases/lists of aviation terrorist

the ground, most particularly at airports, attacks were consulted as potential sources to

quantify aviation terrorism. None of them

making the latter prime targets, either were considered complete or adequate, their

deliberately or by default. Security common weakness being a lack of rigour at

checkpoints in particular have become distinguishing purely criminal incidents from

actual terrorist attacks based on the motives of

chokepoints offering potential prime crowd

perpetrators. All terrorists are also criminals

targets to terrorists. While technologies by default, at least from a rule-of-law

may offer solutions coping with such f laws, perspective, but not all criminals are terrorists.

protecting airports cannot be rethought This lack of reliable statistics on aviation

terrorism led the author to consolidate all

properly without adopting a systemic entries of the seven consulted databases/

approach reaching far beyond the aviation lists. Some 7000 acts of unlawful interference

system. Authorities must use intelligence against civil aviation were compiled into a

Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017 353

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

Duchesneau and Langlois

2071-incident consolidated database called and recommended practices’, International and

Global Aviation Criminal Incidents Database Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 2,

(GACID) and covering the 1931–2016 pp. 433–446.

period. All GACID entries were subsequently (17) ICAO’s Annex 14, Aerodromes, and Annex

categorised in an array of classifications such 19 Safety Management also include important

as region, success, deaths, injuries and modus security-related principles.

operandi. (18) Taleb, N. N. (2007) ‘The Black Swan: The

(6) Many acts of unlawful interference have Impact of the Highly Improbable’, Random

been conducted using more than one modus House, New York.

operandi (MO). For example, many groups (19) Stevens, D., Schell, T., Hamilton, T., Mesic,

or individuals have attacked airports with R., Scott Brown, M., Wei-Min Chan, E.,

the objective of hijacking an aircraft. To Eisman, M., Larson, E. V., Schaffer, M.,

remain empirical, hundreds of entries were Newsome, B., Gibson, J. and Harris, E. (2014)

thus categorised as having several MOs, ‘Near-Term Options for Improving Security at

and statistics were compiled using what was Los Angeles International Airport.’, RAND,

considered as their main MO. Los Angeles, p. 43.

(7) This categorisation represented a challenge. (20) Flynn, S. E. (2004) ‘America the Vulnerable:

Entry descriptions were often sparse, making How Our Government Is Failing to Protect

it rather difficult to clearly establish the Us from Terrorism’, HarperCollins, New York,

motives of perpetrators, especially when no p. 78.

claims were made. Additional research was (21) Gill, P. and Phythian, M. (2008) ‘Intelligence

often conducted to address this lack of clarity. in an Insecure World’, Polity, Malden, MA,

(8) Jenkins, B. M. (1989) ‘The Terrorist Threat to p. 1.

Commercial Aviation’, Rand, Santa Monica, (22) Ibid, p. 7.

CA, p. 7. (23) Smelser, N. J. (2007) ‘The Faces of Terrorism’,

(9) Includes all airport attacks conducted as Princeton University Press, Princeton,

suicide missions. pp. 173–174.

(10) Schiavo, M. F. (2008) ‘Chronology of attacks (24) National Commission on Terrorist Attacks

against civil aviation.’ In Thomas, A. R. (Ed.) upon the United States (2004) ‘The 9/11

Aviation Security Management. Vol. 1, The Commission Report: Final report of the

Context of Aviation Security Management. National Commission on Terrorist Attacks

Praeger, Westport, CT, pp. 142–260. Upon the United States’, authorized edn,

(11) See Atkins, S. E. (2004) ‘Encyclopedia of 1st edn, Norton, New York.

Modern Worldwide Extremists and Extremist (25) International Civil Aviation Organization

Groups’, Greenwood, Westport, CT, p. 248; ‘Economic development’, available at:

Mannes, A. (2004) ‘Profiles in terror: The http://www.icao.int/sustainability/Pages/

Guide to Middle East Terrorist Organizations’, FactsFigures.aspx (accessed 17th July, 2017).

Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD, p. 315. (26) Price, J. C. and Forrest, J. S. (2008) ‘Practical

(12) United International Press (1972) ‘25 die at Aviation Security: Predicting and Preventing

Israeli airport as 3 gunmen from plane fire Future Threats’, Butterworth-Heinemann,

on 250 in a terminal’, New York Times, Burlington, MA, p. 49.

31st May. (27) For one of the best practical books on how to

(13) Other airports attacks causing tens of deaths avoid surprises, maintain operations in case

occurred on 2nd August, 1984 at Madras of catastrophes, and how to manage crises,

Airport, India and on 30th October, 1986 see: Weick, K. E. and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2015)

at Cabinda Airport, Angola. ‘Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High

(14) St. John, P. (1998) ‘The politics of aviation Performance in an Age of Complexity’, John

terrorism’, Terrorism and Political Violence, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ.

Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 27–49. (28) Guihou, X. and Lagadec, P. (2002) ‘La fin du

(15) ICAO, ‘Annex 17 to the Chicago Convention risque zéro’. Éditions d’Organisation, Paris.

on International Civil Aviation’, 1st edn, Doc (29) Mueller, J. and Stewart, M. G. (2011) ‘Terror

8973. Security, and Money: Balancing the Risks,

(16) Akweenda, S. (1986) ‘Prevention of unlawful Benefits, and Costs of Homeland Security’,

interference with aircraft: A study of standards Oxford University Press, New York, p. 14.

354 Delivered by Ingenta to: Henry Stewart Publications

© HENRY STEWART PUBLICATIONS 1750-1938 JOURNAL OF AIRPORT MANAGEMENT VOL. 11, NO. 4, 342–354 AUTUMN/FALL 2017

IP: 185.24.85.49 On: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 15:16:11

Copyright: Henry Stewart Publications

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- JLG 600s-600sj Ingles Manual de ServicioDocument490 paginiJLG 600s-600sj Ingles Manual de Serviciojuampacervantes100% (2)

- Facilities Physical Security MeasuresDocument52 paginiFacilities Physical Security MeasuresNanda Win Lwin100% (4)

- Security Awareness CourseDocument49 paginiSecurity Awareness CourseNanda Win Lwin100% (1)

- 08 Star Trek Comic Strip US - Its A LivingDocument27 pagini08 Star Trek Comic Strip US - Its A LivingColin NaturmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- LNGC Golar Frost - IMO 9253284 - Cargo Operating ManualDocument347 paginiLNGC Golar Frost - IMO 9253284 - Cargo Operating Manualseawolf50Încă nu există evaluări

- 011PDFWhat Became of Air New Zealand's DC-8's Part 1Document13 pagini011PDFWhat Became of Air New Zealand's DC-8's Part 1Leonard G MillsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shore Protection Manual Vol 2Document652 paginiShore Protection Manual Vol 2Jonathan Alberto EscobarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plant CropsDocument40 paginiPlant CropsAmeer Jaffar A. LabanÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Suncity ArcadeDocument10 paginiNew Suncity ArcadePulkit DhuriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gandeza Practical Exercise 2 Criminal ComplaintDocument13 paginiGandeza Practical Exercise 2 Criminal ComplaintRoss AnasarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flexographic Printing - SIEMENSDocument36 paginiFlexographic Printing - SIEMENSMotionCitySoundtrack0% (1)

- Trator 5603 - 06abr09 PDFDocument332 paginiTrator 5603 - 06abr09 PDFIvam JuniorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Terminal Operating Guidelines For Ro Ro Break Bulk and Agricultural Bulk and Ro Ro Automotive TerminalsDocument73 paginiTerminal Operating Guidelines For Ro Ro Break Bulk and Agricultural Bulk and Ro Ro Automotive TerminalsNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Field Assembly ManualDocument41 paginiField Assembly Manualjuan de diosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volvo B13R: A Solid Base For ADocument5 paginiVolvo B13R: A Solid Base For APhilippine Bus Enthusiasts SocietyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vijay HiranandaniDocument25 paginiVijay HiranandaniNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use of Force Training Manual: Safer Communities Through Policing ExcellenceDocument47 paginiUse of Force Training Manual: Safer Communities Through Policing ExcellenceNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Isps Training: Date: 17.11.2013Document66 paginiIsps Training: Date: 17.11.2013Nanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- NPF COVID-19 Guidance Booklet FinalDocument8 paginiNPF COVID-19 Guidance Booklet FinalNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Map Flood-Area in Ayeyarwady and Bago As of 01sep MIMU1515v01 02sep2020 A3 ENGDocument1 paginăMap Flood-Area in Ayeyarwady and Bago As of 01sep MIMU1515v01 02sep2020 A3 ENGNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Integrity Hand Book 2020 JulyDocument62 paginiBusiness Integrity Hand Book 2020 JulyNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Management For NGOs - EnglishDocument46 paginiRisk Management For NGOs - EnglishNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- UNHCR 018 - Assistant Security Officer NOA PN10028522 YangonDocument3 paginiUNHCR 018 - Assistant Security Officer NOA PN10028522 YangonNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- DM Contingency GuidelineDocument50 paginiDM Contingency GuidelineNanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pandemic Business 2Document32 paginiPandemic Business 2Nanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- P Handbook SecurityForces 2017Document138 paginiP Handbook SecurityForces 2017Nanda Win LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dutch Navy 1700-1799Document47 paginiDutch Navy 1700-1799samuraijack7Încă nu există evaluări

- HowStuffWorks - How Bridges WorkDocument6 paginiHowStuffWorks - How Bridges WorkomuletzzÎncă nu există evaluări

- R StudioDocument4 paginiR Studiosrishti bhatejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RajkotDocument29 paginiRajkotBig SurÎncă nu există evaluări

- State Board of Technical Education and Training Andhra Pradesh::Hyderabad. " T.A. Bill Form "Document2 paginiState Board of Technical Education and Training Andhra Pradesh::Hyderabad. " T.A. Bill Form "mass1984Încă nu există evaluări

- Malta Arriva Bus X-Route Itinerary & TimetableDocument24 paginiMalta Arriva Bus X-Route Itinerary & TimetableCharmaineTantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghanada Palace - Vip Block Pending Work 04-04-2013Document4 paginiGhanada Palace - Vip Block Pending Work 04-04-2013miteshsuneriyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambridge IGCSE: MATHEMATICS 0580/42Document20 paginiCambridge IGCSE: MATHEMATICS 0580/42AreejÎncă nu există evaluări

- LMC Ans PP RM2013 GBDocument35 paginiLMC Ans PP RM2013 GBGomez GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9700 m17 Ms 42 PDFDocument16 pagini9700 m17 Ms 42 PDFIG UnionÎncă nu există evaluări

- UAH Proposed Mixed-Use DevelopmentDocument52 paginiUAH Proposed Mixed-Use Developmentpgattis7719100% (1)

- 7 Unit 1 Assessment (Version 1)Document6 pagini7 Unit 1 Assessment (Version 1)Jerome DimaanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CertificateDocument1 paginăCertificateNeo NevizÎncă nu există evaluări

- IT175GDocument43 paginiIT175GKarl ClarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Ngo, 10th Cir. (2007)Document16 paginiUnited States v. Ngo, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solutions On Road: CreepdriveDocument2 paginiSolutions On Road: CreepdriveAx AxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ca 2013 14Document36 paginiCa 2013 14singh1699Încă nu există evaluări