Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ramoncita O. Senador, Petitioner, vs. People of The PHILIPPINES and CYNTHIA JAIME, Respondents

Încărcat de

Ronna0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

22 vizualizări11 paginiCrimpro

Titlu original

Crimpro

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentCrimpro

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

22 vizualizări11 paginiRamoncita O. Senador, Petitioner, vs. People of The PHILIPPINES and CYNTHIA JAIME, Respondents

Încărcat de

RonnaCrimpro

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 11

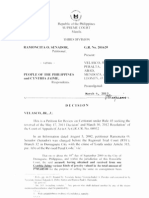

G.R.

No. 201620. March 6, 2013.*

RAMONCITA O. SENADOR, petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE

PHILIPPINES and CYNTHIA JAIME, respondents.

Remedial Law; Criminal Procedure; Pleadings and Practice;

In offenses against property, the materiality of the erroneous designation

of the offended party would depend on whether or not the subject matter

of the offense was sufficiently described and identified.—As correctly held

by the appellate court, Senador’s reliance on Uba is misplaced. In Uba,

the appellant was charged with oral defamation, a crime against honor,

wherein the identity of the person against whom the defamatory words

were directed is a material element. Thus, an erroneous designation of

the person injured is material. On the contrary, in the instant case,

Senador was charged with estafa, a crime against property that does not

absolutely require as indispensable the proper designation of the name

of the offended party. Rather, what is absolutely necessary is the correct

identification of the criminal act charged in the information. Thus, in

case of an error in the designation of the offended party in crimes

against property, Rule 110, Sec. 12 of the Rules of Court mandates the

correction of the information, not its dismissal: SEC. 12. Name of the

offended party.—The complaint or information must state the name and

surname of the person against whom or against whose property the

offense was committed, or any appellation or nickname by which such

person has been or is known. If there is no better way of identifying him,

he must be described under a fictitious name. (a) In offenses against

property, if the name of the offended party is unknown, the property

must be described with such particularity as to properly identify the

offense charged. (b) If the true name of the person against whom or

against whose property the offense was committed is thereafter

disclosed or ascertained, the court must cause such true name to be

inserted in the complaint or information and the record. x x x (Emphasis

supplied.) It is clear from the above provision that in offenses against

property, the materiality of the erroneous designation of the offended

party would depend on whether or not the subject matter of the offense

was sufficiently described and identified.

Same; Same; Same; In offenses against property, if the subject matter

of the offense is generic and not identifiable, such as the money unlawfully

taken, an error in the designation of the offended party is fatal and would

result in the acquittal of the accused. However, if the subject matter of the

offense is specific and identifiable, such as a warrant or a check, an error

in the designation of the offended party is immaterial.—Interpreting the

previously discussed cases, We conclude that in offenses against

property, if the subject matter of the offense is generic and not

identifiable, such as the money unlawfully taken as in Lahoylahoy, an

error in the designation of the offended party is fatal and would result in

the acquittal of the accused. However, if the subject matter of the

offense is specific and identifiable, such as a warrant, as in Kepner, or a

check, such as in Sayson and Ricarze, an error in the designation of the

offended party is immaterial. In the present case, the subject matter of

the offense does not refer to money or any other generic property.

Instead, the information specified the subject of the offense as “various

kinds of jewelry valued in the total amount of P705,685.00.” The charge

was thereafter sufficiently fleshed out and proved by the Trust Receipt

Agreement signed by Senador and presented during trial, which

enumerates these “various kinds of jewelry valued in the total amount

of PhP 705,685,”

PETITION for review on certiorari of the decision and

resolution of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Flores & Flores Law Office for petitioner.

Office of the Solicitor General for public respondent.

VELASCO, JR., J.:

This is a Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45

seeking the reversal of the May 17, 2011 Decision1 and March

30, 2012 Resolution2 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-

G.R. CR. No. 00952.

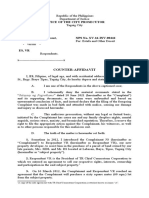

In an Information dated August 5, 2002, petitioner

Ramoncita O. Senador (Senador) was charged before the

Regional Trial Court (RTC), Branch 32 in Dumaguete City with

the crime of Estafa under Article 315, par. 1(b) of the Revised

Penal Code,3 viz.:

_______________

1 Rollo, pp. 44-55. Penned by Associate Justice Victoria Isabel A. Paredes and

concurred in by Associate Justices Edgardo L. Delos Santos and Ramon Paul L.

Hernando.

2 Id., at pp. 61-63.

3 Art. 315. Swindling (estafa). Any person who shall defraud another by any of

the means mentioned hereinbelow shall be punished by:

x x x x

1. With unfaithfulness or abuse of confidence, namely:

x x x x

(b) By misappropriating or converting, to the prejudice of another, money,

goods or any other personal property received by the offender in trust, or on

commission, or for administration, or under any other obligation involving the

duty to make delivery of, or to return the same, even though such obligation be

totally or partially guaranteed by a bond; or by denying having received such

money, goods, or another property.

That on or about the 10th day of September 2000 in the City of

Dumaguete, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable

Court, the said accused, having obtained and received from one Cynthia

Jaime various kinds of jewelry valued in the total amount of

P705,685.00 for the purpose of selling the same on consignment basis

with express obligation to account for and remit the entire proceeds of

the sale if sold or to return the same if unsold within an agreed period of

time and despite repeated demands therefor, did, then and there

willfully, unlawfully and feloniously fail to remit proceeds of the sale of

said items or to return any of the items that may have been unsold to

said Cynthia Jaime but instead has willfully, unlawfully and feloniously

misappropriated, misapplied and converted the same to his/her own

use and benefit to the damage and prejudice of said Cynthia Jaime in the

aforementioned amount of P705,685.00.4 (Emphasis supplied.)

Upon arraignment, petitioner pleaded “not guilty.” Thereafter,

trial on the merits ensued.

The prosecution’s evidence sought to prove the following facts:

Rita Jaime (Rita) and her daughter-in-law, Cynthia Jaime

(Cynthia), were engaged in a jewelry business. Sometime in the

first week of September 2000, Senador went to see Rita at her

house in Guadalupe Heights, Cebu City, expressing her interest

to see the pieces of jewelry that the latter was selling. On

September 10, 2000, Rita’s daughter-in-law and business

partner, Cynthia, delivered to Senador several pieces of jewelry

worth seven hundred five thousand six hundred eighty five

pesos (PhP 705,685).5

In the covering Trust Receipt Agreement signed by Cynthia and

Senador, the latter undertook to sell the jewelry thus delivered

on commission basis and, thereafter, to remit the proceeds of

the sale, or return the unsold items to Cynthia within fifteen

(15) days from the delivery.6 However, as events

_______________

4 Rollo, p. 46.

5 Id., at p. 47.

6 Id.

turned out, Senador failed to turn over the proceeds of the sale

or return the unsold jewelry within the given period.7

Thus, in a letter dated October 4, 2001, Rita demanded from

Senador the return of the unsold jewelry or the remittance of

the proceeds from the sale of jewelry entrusted to her. The

demand fell on deaf ears prompting Rita to file the instant

criminal complaint against Senador.8

During the preliminary investigation, Senador tendered to Rita

Keppel Bank Check No. 0003603 dated March 31, 2001 for the

amount of PhP 705,685,9 as settlement of her obligations.

Nonetheless, the check was later dishonored as it was drawn

against a closed account.10

Senador refused to testify and so failed to refute any of the

foregoing evidence of the prosecution, and instead, she relied

on the defense that the facts alleged in the Information and the

facts proven and established during the trial differ. In

particular, Senador asserted that the person named as the

offended party in the Information is not the same person who

made the demand and filed the complaint. According to

Senador, the private complainant in the Information went by

the name “Cynthia Jaime,” whereas, during trial, the private

complainant turned out to be “Rita Jaime.” Further, Cynthia

Jaime was never presented as witness. Hence, citing People v.

Uba, et al.11 (Uba) and United States v. Lahoylahoy and Madanlog

(Lahoylahoy),12 Senador would insist on her acquittal on the

postulate that her constitutional right to be informed of the

nature of the accusation against her has been violated.

_______________

7 Id.

8 Id.

9 Folder of Exhibits, p. 21.

10 Id., at p. 22.

11 106 Phil. 332 (1959).

12 38 Phil. 330 (1918).

Despite her argument, the trial court, by Decision dated June

30, 2008, found Senador guilty as charged and sentenced as

follows:

WHEREFORE, the Court finds RAMONCITA SENADOR guilty beyond

reasonable doubt of the crime of ESTAFA under Par. 1 (b), Art. 315 of

the Revised Penal Code, and is hereby sentenced to suffer the penalty of

four (4) years and one (1) day of prision correccional as minimum to

twenty (20) years of reclusion temporal as maximum and to indemnify

the private complainants, RITA JA[I]ME and CYNTHIA JA[I]ME, the

following: 1) Actual Damages in the amount of P695,685.00 with

interest at the legal rate from the filing of the Information until fully

paid; 2) Exemplary Damages in the amount of P100,000.00; and 3) the

amount of P50,000 as Attorney’s fees.

Senador questioned the RTC Decision before the CA. However,

on May 17, 2011, the appellate court rendered a Decision

upholding the finding of the RTC that the prosecution

satisfactorily established the guilt of Senador beyond

reasonable doubt. The CA opined that the prosecution was able

to establish beyond reasonable doubt the following undisputed

facts, to wit: (1) Senador received the pieces of jewelry in trust

under the obligation or duty to return them; (2) Senador

misappropriated or converted the pieces of jewelry to her

benefit but to the prejudice of business partners, Rita and

Cynthia; and (3) Senador failed to return the pieces of jewelry

despite demand made by Rita.

Further, the CA––finding that Uba13 is not applicable since

Senador is charged with estafa, a crime against property and

not oral defamation, as in Uba––ruled:

WHEREFORE, the June 30, 2008 Judgment of the Regional Trial Court,

Branch 32, Dumaguete City, in Criminal Case No. 16010, finding accused

appellant guilty beyond reasonable doubt of Estafa is hereby AFFIRMED

in toto.

_______________

13 Supra note 11.

675

VOL. 692, MARCH 6, 2013 67

5

Senador vs. People

SO ORDERED.

Senador filed a Motion for Reconsideration but it was denied in

a Resolution dated March 30, 2012. Hence, the present petition

of Senador.

The sole issue involved in the instant case is whether or not an

error in the designation in the Information of the offended

party violates, as petitioner argues, the accused’s constitutional

right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation

against her, thus, entitling her to an acquittal.

The petition is without merit.

At the outset, it must be emphasized that variance between the

allegations of the information and the evidence offered by the

prosecution does not of itself entitle the accused to an

acquittal,14 more so if the variance relates to the designation of

the offended party, a mere formal defect, which does not

prejudice the substantial rights of the accused.15

As correctly held by the appellate court, Senador’s reliance on

Uba is misplaced. In Uba, the appellant was charged with oral

defamation, a crime against honor, wherein the identity of the

person against whom the defamatory words were directed is a

material element. Thus, an erroneous designation of the person

injured is material. On the contrary, in the instant case,

Senador was charged with estafa, a crime against property that

does not absolutely require as indispensable the proper

designation of the name of the offended party. Rather, what is

absolutely necessary is the correct identification of the

criminal act charged in the information.16 Thus, in case of an

error in the designation of the offended party in

_______________

14 People v. Catli, No. L-11641, November 29, 1962, 6 SCRA 642, 647. (Emphasis

supplied.)

15 Ricarze v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 160451, February 9, 2007, 515 SCRA 302,

321.

16 Id.; citing Sayson v. People, No. L-51745, October 28, 1988, 166 SCRA 680.

676

6 SUPREME COURT

7 REPORTS ANNOTATED

6

Senador vs. People

crimes against property, Rule 110, Sec. 12 of the Rules of Court

mandates the correction of the information, not its dismissal:

SEC. 12. Name of the offended party.—The complaint or information

must state the name and surname of the person against whom or

against whose property the offense was committed, or any appellation

or nickname by which such person has been or is known. If there is no

better way of identifying him, he must be described under a fictitious

name.

(a) In offenses against property, if the name of the offended party is

unknown, the property must be described with such particularity as to

properly identify the offense charged.

(b) If the true name of the person against whom or against whose

property the offense was committed is thereafter disclosed or

ascertained, the court must cause such true name to be inserted in the

complaint or information and the record. x x x (Emphasis supplied.)

It is clear from the above provision that in offenses against

property, the materiality of the erroneous designation of the

offended party would depend on whether or not the subject

matter of the offense was sufficiently described and identified.

Lahoylahoy cited by Senador supports the doctrine that if

the subject matter of the offense is generic or one which is not

described with such particularity as to properly identify the

offense charged, then an erroneous designation of the offended

party is material and would result in the violation of the

accused’s constitutional right to be informed of the nature and

cause of the accusation against her. Such error, Lahoylahoy

teaches, would result in the acquittal of the accused, viz.:

The second sentence of section 7 of General Orders No. 58 declares that

when an offense shall have been described with sufficient certainty to

identify the act, an erroneous allegation as to the person injured shall be

deemed immaterial. We are of the opinion that

677

VOL. 692, MARCH 6, 2013 67

7

Senador vs. People

this provision can have no application to a case where the name of the

person injured is matter of essential description as in the case at bar;

and at any rate, supposing the allegation of ownership to be eliminated,

the robbery charged in this case would not be sufficiently identified. A

complaint stating, as does the one now before us, that the defendants

“took and appropriated to themselves with intent of gain and against

the will of the owner thereof the sum of P100” could scarcely be

sustained in any jurisdiction as a sufficient description either of the act

of robbery or of the subject of the robbery. There is a saying to the effect

that money has no earmarks; and generally speaking the only way

money, which has been the subject of a robbery, can be described or

identified in a complaint is by connecting it with the individual who was

robbed as its owner or possessor. And clearly, when the offense has

been so identified in the complaint, the proof must correspond upon

this point with the allegation, or there can be no conviction.17 (Emphasis

supplied.)

In Lahoylahoy, the subject matter of the offense was money in

the total sum of PhP 100. Since money is generic and has no

earmarks that could properly identify it, the only way that it

(money) could be described and identified in a complaint is by

connecting it to the offended party or the individual who was

robbed as its owner or possessor. Thus, the identity of the

offended party is material and necessary for the proper

identification of the offense charged. Corollary, the erroneous

designation of the offended party would also be material, as

the subject matter of the offense could no longer be described

with such particularity as to properly identify the offense

charged.

The holdings in United States v. Kepner,18 Sayson v. People,19 and

Ricarze v. Court of Appeals20 support the doctrine that if the

subject matter of the offense is specific or one described with

such particularity as to properly identify the

_______________

17 Supra note 12, at pp. 336-337.1

18 1 Phil. 519 (1902).

19 Supra note 16.

20 Supra note 15.

678

6 SUPREME COURT

7 REPORTS ANNOTATED

8

Senador vs. People

offense charged, then an erroneous designation of the offended

party is not material and would not result in the violation of

the accused’s constitutional right to be informed of the nature

and cause of the accusation against her. Such error would not

result in the acquittal of the accused.

In the 1902 case of Kepner, this Court ruled that the erroneous

designation of the person injured by a criminal act is not

material for the prosecution of the offense because the subject

matter of the offense, a warrant, was sufficiently identified

with such particularity as to properly identify the particular

offense charged. We held, thus:

The allegation of the complaint that the unlawful misappropriation of

the proceeds of the warrant was to the prejudice of Aun Tan may be

disregarded by virtue of section 7 of General Orders, No. 58, which

declares that when an offense shall have been described in the

complaint with sufficient certainty to identify the act, an erroneous

allegation as to the person injured shall be deemed immaterial. In any

event the defect, if defect it was, was one of form which did not tend to

prejudice any substantial right of the defendant on the merits, and can

not, therefore, under the provisions of section 10 of the same order,

affect the present proceeding.21 (Emphasis supplied.)

In Sayson, this Court upheld the conviction of Sayson for

attempted estafa, even if there was an erroneous allegation as

to the person injured because the subject matter of the offense,

a check, is specific and sufficiently identified. We held, thus:

In U.S. v. Kepner x x x, this Court laid down the rule that when an offense

shall have been described in the complaint with sufficient certainty as to

identify the act, an erroneous allegation as to the person injured shall be

deemed immaterial as the same is a mere formal defect which did not

tend to prejudice any substantial right of the defendant. Accordingly, in

the aforementioned case,

_______________

21 Supra note 18, at p. 526.

679

VOL. 692, MARCH 6, 2013 67

9

Senador vs. People

which had a factual backdrop similar to the instant case, where the

defendant was charged with estafa for the misappropriation of the

proceeds of a warrant which he had cashed without authority, the

erroneous allegation in the complaint to the effect that the unlawful act

was to the prejudice of the owner of the cheque, when in reality the

bank which cashed it was the one which suffered a loss, was held to be

immaterial on the ground that the subject matter of the estafa, the

warrant, was described in the complaint with such particularity as to

properly identify the particular offense charged. In the instant suit for

estafa which is a crime against property under the Revised Penal Code,

since the check, which was the subject-matter of the offense, was

described with such particularity as to properly identify the offense

charged, it becomes immaterial, for purposes of convicting the accused,

that it was established during the trial that the offended party was

actually Mever Films and not Ernesto Rufino, Sr. nor Bank of America as

alleged in the information.”22 (Emphasis supplied.)

In Ricarze, We reiterated the doctrine espousing an erroneous

designation of the person injured is not material because the

subject matter of the offense, a check, was sufficiently

identified with such particularity as to properly identify the

particular offense charged.23

Interpreting the previously discussed cases, We conclude that

in offenses against property, if the subject matter of the offense

is generic and not identifiable, such as the money unlawfully

taken as in Lahoylahoy, an error in the designation of the

offended party is fatal and would result in the acquittal of the

accused. However, if the subject matter of the offense is

specific and identifiable, such as a warrant, as in Kepner, or a

check, such as in Sayson and Ricarze, an error in the

designation of the offended party is immaterial.

_______________

22 Supra note 16, at p. 693.

23 Supra note 15.

680

6 SUPREME COURT

8 REPORTS ANNOTATED

0

Senador vs. People

In the present case, the subject matter of the offense does not

refer to money or any other generic property. Instead, the

information specified the subject of the offense as “various

kinds of jewelry valued in the total amount of P705,685.00.”

The charge was thereafter sufficiently fleshed out and proved

by the Trust Receipt Agreement24 signed by Senador and

presented during trial, which enumerates these “various kinds

of jewelry valued in the total amount of PhP 705,685,” viz.:

Quality Description

1 #1878 1 set rositas

w/brills 14 kt. 8.5

grams

1 #2126 1 set

w/brills 14 kt. 8.3

grams

1 #1416 1 set tri-

color rositas

w/brills 14 kt. 4.1

grams

1 #319 1 set creolla

w/brills 14 kt. 13.8

grams

1 #1301 1 set creolla

2 colors w/brills

20.8 grams

1 #393 1 set tepero &

marquise 14kt. 14

grams

1 #2155 1 yg.

Bracelet w brills

ruby and blue

sapphire 14 kt. 28

grams

1 #1875 1 set yg. w/

choker 14 kt. (oval)

14.6 grams

1 #2141 1 yg. w/

pearl & brills 14 kt.

8.8 grams

1 #206 1 set double

sampaloc creolla 14

kt. 14.2 grams

1 # 146 1 set princess

cut brills 13.6

grams

1 # 2067 1 pc. brill

w/ pearl & brill 14

kt. 2.0 grams

1 #2066 1 pc.

earrings w/ pearl &

brills 14 kt. 4.5

grams

1 #1306 1 set creolla

w/ brills 14 kt. 12.6

grams

1 #1851 1 pc. lady’s

ring w/ brills 14 kt.

7.8 grams

1 # 1515 1 set w/

brills 14 kt. 11.8

grams

1 #1881 1 pc yg. ring

w/princess cut 14

kt. 4.1 grams

_______________

24 Folder of exhibits, p. 11.

681

VOL. 692, MARCH 6, 68

2013 1

Senador vs. People

Thus, it is the doctrine elucidated in Kepner, Sayson, and

Ricarze that is applicable to the present case, not the ruling in

Uba or Lahoylahoy. The error in the designation of the offended

party in the information is immaterial and did not violate

Senador’s constitutional right to be informed of the nature and

cause of the accusation against her.

Lest it be overlooked, Senador offered to pay her obligations

through Keppel Check No. 0003603, which was dishonored

because it was drawn against an already closed account. The

offer indicates her receipt of the pieces of jewelry thus

described and an implied admission that she misappropriated

the jewelries themselves or the proceeds of the sale. Rule 130,

Section 27 states:

In criminal cases, except those involving quasi-offenses (criminal

negligence) or those allowed by law to be compromised, an offer of

compromise by the accused may be received in evidence as implied

admission of guilt. (Emphasis supplied.)

Taken together, the CA did not err in affirming petitioner’s

conviction for the crime of estafa.

In light of current jurisprudence,25 the Court, however, finds the

award of exemplary damages excessive. Art. 2229 of the Civil

Code provides that exemplary damages may be imposed by

way of example or correction for the public good. Nevertheless,

“exemplary damages are imposed not to enrich one party or

impoverish another, but to serve as a deterrent against or as a

negative incentive to curb socially deleterious actions.”26 On

this basis, the award of exemplary damages in the amount of

PhP 100,000 is reduced to PhP 30,000.

_______________

25 People v. Combate, G.R. No. 189301, December 15, 2010, 638 SCRA 797.

26 Yuchengco v. The Manila Chronicle Publishing Coporation, G.R. No. 184315,

November 28, 2011, 661 SCRA 392, 405-406.

682

6 SUPREME COURT

8 REPORTS ANNOTATED

2

Senador vs. People

WHEREFORE, the Decision dated May 17, 2011 and Resolution

dated March 30, 2012 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CR. No.

00952, finding Ramoncita Senador guilty beyond reasonable

doubt of the crime of ESTAFA under par. 1(b), Art. 315 of the

Revised Penal Code, are hereby AFFIRMED with

MODIFICATION that the award of exemplary damages be

reduced to PhP 30,000.

SO ORDERED.

Peralta, Abad, Mendoza and Leonen, JJ., concur.

Judgment and resolution affirmed with modification.

Notes.—The offense of estafa committed with abuse of

confidence has the following elements under Article 315,

paragraph 1(b) of the Revised Penal Code, as amended: (a) that

money, goods or other personal property is received by the

offender in trust or on commission, or for administration, or

under any other obligation involving the duty to make delivery

of or to return the same[;] (b) that there be misappropriation

or conversion of such money or property by the offender, or

denial on his part of such receipt[;] (c) that such

misappropriation or conversion or denial is to the prejudice of

another; and (d) there is demand by the offended party to the

offender. (Magtira vs. People, 667 SCRA 607 [2012])

The decisive factor in determining the criminal and civil

liability for the crime of estafa depends on the value of the

thing or the amount defrauded. (Ibid.)

——o0o——

© Copyright 2017 Central Book Supply, Inc. All rights reserved.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Senador vs. PeopleDocument5 paginiSenador vs. PeopleRenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Senador vs. PeopleDocument4 paginiSenador vs. PeopleShery Ann ContadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 Senador Vs PeopleDocument5 pagini10 Senador Vs PeopleKristelle IgnacioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Senador V People March 6, 2013 (DIGEST)Document3 paginiSenador V People March 6, 2013 (DIGEST)Reina Anne JaymeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14 - Senador V PeopleDocument2 pagini14 - Senador V PeopleAndrea RioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Search: Today Is Sunday, June 15, 2014Document11 paginiSearch: Today Is Sunday, June 15, 2014Seffirion69Încă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest 1Document8 paginiCase Digest 1JSJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Senador vs. People, G.R. No. 201620, 06 March 2013Document2 paginiSenador vs. People, G.R. No. 201620, 06 March 2013Gwendelyn Peñamayor-MercadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- RAMONCITA O. SENADOR v. PEOPLEDocument2 paginiRAMONCITA O. SENADOR v. PEOPLEAneesh AlliceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Senador VS, PeopleDocument2 paginiSenador VS, PeopleLiezl Oreilly Villanueva100% (4)

- 10.) Senador Vs PeopleDocument2 pagini10.) Senador Vs Peoplembr425Încă nu există evaluări

- Sample Counter-Affidavit (JMTE)Document7 paginiSample Counter-Affidavit (JMTE)JM EvangelistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA!/lONCITA 0. G.R. No. 201620Document9 paginiRA!/lONCITA 0. G.R. No. 201620DO SOLÎncă nu există evaluări

- SEC 12.01 - Senador V People, GR No. 201620, 692 SCRA 669 PDFDocument13 paginiSEC 12.01 - Senador V People, GR No. 201620, 692 SCRA 669 PDFabo8008Încă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest 2019-2020Document16 paginiCase Digest 2019-2020Ronald Lubiano Cuartero100% (1)

- Qualified TheftDocument20 paginiQualified TheftSawewong Wong100% (3)

- Legal Profession: I. Law As A ProfessionDocument18 paginiLegal Profession: I. Law As A ProfessionM GÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case No. 1Document5 paginiCase No. 1Maida Rahma SalisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 179061Document3 paginiG.R. No. 179061Nor-Ayn M. MautenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sufficiency of Complaint or Information. A Complaint or Information Is Sufficient If It States TheDocument35 paginiSufficiency of Complaint or Information. A Complaint or Information Is Sufficient If It States TheDiane Althea Valera PenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- EstafaDocument4 paginiEstafaEppie Severino100% (1)

- Christina B. Castillo vs. Philip Salvador: Ponente: J. Peralta FactsDocument5 paginiChristina B. Castillo vs. Philip Salvador: Ponente: J. Peralta FactsDennis Jay Dencio ParasÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 193854 September 24, 2012 People of The Philippines, Appellee, DINA DULAY y PASCUAL, AppellantDocument27 paginiG.R. No. 193854 September 24, 2012 People of The Philippines, Appellee, DINA DULAY y PASCUAL, Appellantarden1imÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carmen Liwanag, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and The People of The Philippines, Represented by The Solicitor General, RespondentsDocument9 paginiCarmen Liwanag, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and The People of The Philippines, Represented by The Solicitor General, RespondentsmonchievaleraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument3 paginiCase DigestimXinYÎncă nu există evaluări

- 115354-2001-People v. Viernes y IldefonsoDocument21 pagini115354-2001-People v. Viernes y IldefonsoHans Henly GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Troscript - 6 15 10Document5 paginiTroscript - 6 15 10willÎncă nu există evaluări

- PALE DagiestDocument76 paginiPALE DagiestPatrice ErniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Ethics DigestsDocument3 paginiLegal Ethics DigestsLily JadeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument3 paginiCase DigestimXinYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathay vs. PP and Gandionco DGDocument6 paginiMathay vs. PP and Gandionco DGKimberly Ramos100% (1)

- G.R. No. 183879 PDFDocument6 paginiG.R. No. 183879 PDFRon Russell Solivio MagbalonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appellee Appellant The Solicitor General Public Attorney's OfficeDocument23 paginiAppellee Appellant The Solicitor General Public Attorney's OfficeJohn Paul EslerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sy vs. PeopleDocument7 paginiSy vs. PeopleempuyÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. Amestuzo 361 SCRA 184, July 12, 2001Document16 paginiPeople vs. Amestuzo 361 SCRA 184, July 12, 2001CassieÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. ARMANDO RODAS1 and JOSE RODAS, SR., Accused-Appellants. G.R. NO. 175881: August 28, 2007Document13 paginiPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. ARMANDO RODAS1 and JOSE RODAS, SR., Accused-Appellants. G.R. NO. 175881: August 28, 2007Kaye Kiikai OnahonÎncă nu există evaluări

- LAWYERDocument11 paginiLAWYERHermay BanarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- GP Liwanag V CA 281 SCRA 225Document4 paginiGP Liwanag V CA 281 SCRA 225sunsetsailor85Încă nu există evaluări

- US V DichaoDocument3 paginiUS V Dichaorgtan3Încă nu există evaluări

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents Raymundo A. Armovit Mary Concepcion BautistaDocument6 paginiPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents Raymundo A. Armovit Mary Concepcion BautistaValen Grace MalabagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patula v. PeopleDocument25 paginiPatula v. PeopleNinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court: Republic of The Philippines Baguio City Third DivisionDocument4 paginiSupreme Court: Republic of The Philippines Baguio City Third DivisionWonder WomanÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSB Group Inc. VS GoDocument7 paginiBSB Group Inc. VS GoNoo NooooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Special Penal LawsDocument64 paginiSpecial Penal LawsFame Gonzales PortinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crimpro Case 6-15-23Document9 paginiCrimpro Case 6-15-23Arlyn TagayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- People VS Puig and PorrasDocument1 paginăPeople VS Puig and PorrasJologs WasalakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case 6 - ART. 1953Document5 paginiCase 6 - ART. 1953krizzledelapenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mercullo vs. RamonDocument13 paginiMercullo vs. RamondollyccruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recuerdo vs. PeopleDocument3 paginiRecuerdo vs. PeopleRoyce PedemonteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule - 110.pdf - Filename - UTF-8''2. Rule 110-1Document7 paginiRule - 110.pdf - Filename - UTF-8''2. Rule 110-1Prince Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Us vs. KarelsenDocument7 paginiUs vs. KarelsenLiza Marie Lanuza SabadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V EscordialDocument24 paginiPeople V Escordialanonymous0914Încă nu există evaluări

- People v. AmestuzoDocument17 paginiPeople v. AmestuzoDustin NitroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roque vs. People 444 SCRA 98, G.R. No. 138954, November 25, 2004 Qualified TheftDocument6 paginiRoque vs. People 444 SCRA 98, G.R. No. 138954, November 25, 2004 Qualified TheftJerahmeel CuevasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Entila & Entila Law OfficesDocument24 paginiPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Entila & Entila Law OfficesChristian VillarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updates in Legal EthicsDocument76 paginiUpdates in Legal EthicsRyan CalanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambaliza Vs Cristobal-TenorioDocument6 paginiCambaliza Vs Cristobal-TenorioDora the ExplorerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 8 Case Digests - Lawyer - S Fiduciary ObligationsDocument12 paginiChapter 8 Case Digests - Lawyer - S Fiduciary ObligationsMiguel C. SollerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motions, Affidavits, Answers, and Commercial Liens - The Book of Effective Sample DocumentsDe la EverandMotions, Affidavits, Answers, and Commercial Liens - The Book of Effective Sample DocumentsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (14)

- Political Law ReviewDocument5 paginiPolitical Law ReviewRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2004 Rules On Notarial Practice - AM 02-8-13-SC PDFDocument20 pagini2004 Rules On Notarial Practice - AM 02-8-13-SC PDFirditchÎncă nu există evaluări

- A. Summary - Chapter Viii: Marriage and Divorce What Are The Conflict of Laws Pertaining To Marriage?Document10 paginiA. Summary - Chapter Viii: Marriage and Divorce What Are The Conflict of Laws Pertaining To Marriage?RonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political LawDocument364 paginiPolitical LawJingJing Romero100% (99)

- Quamto Criminal Law 2017Document44 paginiQuamto Criminal Law 2017Robert Manto88% (16)

- Bank Certificate of Indebtedness (CBCI) - It Was Only Through One of Its Officers by Which TheDocument1 paginăBank Certificate of Indebtedness (CBCI) - It Was Only Through One of Its Officers by Which TheRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule 30 - TrialDocument11 paginiRule 30 - TrialRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estate & Donors Tax Case DigestsDocument25 paginiEstate & Donors Tax Case DigestsRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leveriza Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument2 paginiLeveriza Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revenue Regulations 02-03Document22 paginiRevenue Regulations 02-03Anonymous HIBt2h6z7Încă nu există evaluări

- CredTrans Cases Nov.24 PDFDocument29 paginiCredTrans Cases Nov.24 PDFRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leveriza Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument2 paginiLeveriza Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Limpot v. Court of AppealsDocument6 paginiLimpot v. Court of AppealsJay-Em DaguioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 in Re Manzano LopezDocument1 pagină02 in Re Manzano LopezRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yau Chu v. Court of AppealsDocument2 paginiYau Chu v. Court of AppealsAgee Romero-Valdes100% (2)

- Up Law Boc Labor 2016 2 PDFDocument228 paginiUp Law Boc Labor 2016 2 PDFjohnisflyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revenue Regulations 02-03Document22 paginiRevenue Regulations 02-03Anonymous HIBt2h6z7Încă nu există evaluări

- Final PolignDocument308 paginiFinal PolignRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- De Lima Vs GatdulaDocument4 paginiDe Lima Vs GatdulaRonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20 Sps. Gonzaga Vs CADocument2 pagini20 Sps. Gonzaga Vs CAHenry LÎncă nu există evaluări

- Torts 2017Document9 paginiTorts 2017RonnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Additional Case DigestsDocument5 paginiAdditional Case DigestsAlex RabanesÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Critical Study of The Role of Prosecutor in Criminal LawDocument7 paginiA Critical Study of The Role of Prosecutor in Criminal Lawhari sudhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 NDDocument100 pagini2 NDAngelica MaquiÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Max H. Homer A/K/A Max H. Homer, JR., 545 F.2d 864, 3rd Cir. (1976)Document7 paginiUnited States v. Max H. Homer A/K/A Max H. Homer, JR., 545 F.2d 864, 3rd Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dhananjay Shanker Shetty Vs State of Maharashtra - 102616Document9 paginiDhananjay Shanker Shetty Vs State of Maharashtra - 102616Rachana GhoshtekarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vasan Singh v. PPDocument5 paginiVasan Singh v. PPAishah MunawarahÎncă nu există evaluări

- ESTAFA AND ILLEGAL RECRUITMENT CaseDocument9 paginiESTAFA AND ILLEGAL RECRUITMENT CaseBing Viloria-YapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conflict of Laws Case DigestsDocument14 paginiConflict of Laws Case DigestsKayelyn LatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crim Pro Case DigestDocument29 paginiCrim Pro Case DigestMarie100% (2)

- Court Interpreter Vacancies in GautengDocument2 paginiCourt Interpreter Vacancies in GautengLarry GoodwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V VillaramaDocument3 paginiPeople V VillaramaMaureen Anne dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- 134) de Los Santos-Dio V CaguioaDocument2 pagini134) de Los Santos-Dio V CaguioaAlfonso DimlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crimpro Syllabus Part 1Document4 paginiCrimpro Syllabus Part 1Fiona FedericoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benares Vs Lim MacalaladDocument2 paginiBenares Vs Lim MacalaladWILHELMINA CUYUGANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal Procedure Rule 110 SummaryDocument9 paginiCriminal Procedure Rule 110 SummaryDessa Ruth Reyes100% (1)

- Acid Attack Moot ProblemDocument5 paginiAcid Attack Moot ProblemRajesh KhanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memorandum For The Accused: People of The Philippines (Plaintiff)Document5 paginiMemorandum For The Accused: People of The Philippines (Plaintiff)Jaco Rafael AgdeppaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 16 People Vs JamilosaDocument5 pagini16 People Vs JamilosaKastin SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- DIR Format FormDocument29 paginiDIR Format FormPraveen KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petition For Bail de LeyosDocument6 paginiPetition For Bail de LeyosDulay R CathyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pena vs. CA, Sps. Yap, PAMBUSCO, Jesus Doming, Joaquin Briones, Salvador Bernardez, Marcelino Enriquez, Edgardo ZabatDocument18 paginiPena vs. CA, Sps. Yap, PAMBUSCO, Jesus Doming, Joaquin Briones, Salvador Bernardez, Marcelino Enriquez, Edgardo ZabatJoshua AmancioÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 142030 - Gallardo vs. PPDocument5 paginiG.R. No. 142030 - Gallardo vs. PPseanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poonam Singh Vs State & OrsDocument13 paginiPoonam Singh Vs State & OrsMohan PatnaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- FactsDocument38 paginiFactsShiela VenturaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crim Pro Full CasesDocument92 paginiCrim Pro Full CasesCasey IbascoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Commercial Farmers Union Et Al. v. Minister of Lands and Rural Resettlement Et Al. (Nov. 26, 2010)Document30 paginiCommercial Farmers Union Et Al. v. Minister of Lands and Rural Resettlement Et Al. (Nov. 26, 2010)ILIBdocuments100% (8)

- 2 Heirs of Delgado v. Gonzales-Converted (With Watermark) B2021 PDFDocument3 pagini2 Heirs of Delgado v. Gonzales-Converted (With Watermark) B2021 PDFAbegail GaledoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filcro Cases On The EmployersDocument5 paginiFilcro Cases On The Employerskerstine03024056Încă nu există evaluări

- Adversarial Inquisitions: Rethinking The Search For The Truth Keith A. FindleyDocument32 paginiAdversarial Inquisitions: Rethinking The Search For The Truth Keith A. FindleyJohn TeiramfdsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Efraim GenuinoDocument6 paginiEfraim GenuinoJobelle NervarÎncă nu există evaluări