Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Joyas Ingles Algunas

Încărcat de

Ag AndreiaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Joyas Ingles Algunas

Încărcat de

Ag AndreiaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

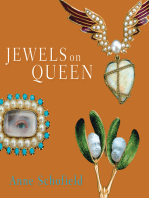

Jewels in Spain

Jewels in Spain 1500 – 1800

1500 – 1800

THE HISPANIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA PRISCILLA E. MULLER

CENTER FOR SPAIN IN AMERICA

CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS EUROPA HISPÁNICA

Distributed by Ediciones El Viso, Madrid

www.edicioneselviso.com

0393viso_sobrecubiertas#2.indd 2 19/04/12 15:50

0393viso_001-005#.indd 2 10/04/12 11:32

Foreword

Joy, and jewel as well as the Spanish joya, the context of historical and stylistic devel-

are cognate nouns having among their opments.

antecedents the Latin gaudium, meaning This new edition of my Jewels in

joy, gladness and delight, and jocus, a Spain 1500–1800, first published some

plaything, toy or trinket. But jewel, a prod- forty years ago, presents major enhance-

uct of the intervention of the Middle En- ments. New color illustrations replace

glish and Old French juel, no longer con- most black-and-white reproductions.

veys, as might joya for English readers Changes in classification and/or location

aware of its cognate joy, the sense of plea- of objects are incorporated in revised

surable response expressed by its Spanish illustration captions. And a greatly enlarged

equivalent. Thus the more evocative “Joyas bibliography acknowledges the prolifer-

in Spain,” rather than “Jewels in Spain,” ation of interest in the study of jewels

would, if practicable, have been my pref- during more than a quarter century.

erence in titling this work. The many significant developments

Jewels in and not of Spain, or sim- that have come forth to expand our knowl-

ply “Spanish jewels,” is a delimitation edge of jewels in the Peninsula (and else-

which could not be obviated, for, as many where) encompass scholarly researches

realize, jewels encountered within nation- and publications, increased access to

al borders are not necessarily of that nation archival resources, discoveries of pieces

in origin or style. A second delimitation, long hidden from view, and new scien-

that of the three-century time span con- tific technologies. The last, for example,

sidered, while unfortunately eliminating can confirm that some prized jewels

such treasures as Spain’s Visigothic crowns thought to date from 1500–1800 are in

or the works of Barcelona’s Art Nouveau fact of much later date, and therefore to

jewelers, permits concentration on those be identified as “Renaissance-style” or

years in which goldsmiths in Spain as “Renaissance-Revival” jewels.

elsewhere realized their fullest triumph The heightened publication of inven-

as individual artist-craftsmen. Indeed, I tories recording jewels once in royal col-

can only hope to have treated fairly by lections, church treasuries, and in private

synthesization the vast quantity of source collections alerts us to their kinds. Yet,

material available encompassing these descriptive details are uncommon. For-

three centuries. tunately, a visual complement exists in

Limits other than those indicated guild examination drawings submitted

in the title have also been drawn. Crown by young Barcelona goldsmiths through

jewels, jewels decorating religious im- more than three centuries. Chronologi-

ages, jeweled chivalric order pendants, are cally arranged in the Llibres de Passanties

not per se the subject of this study; they preserved in the city’s Arxiu Històric, the

have been introduced, however, within earliest designs are of around 1500, while

0393viso_006-014#3.indd 6 10/04/12 11:32

subsequent drawings are signed and dat- long submerged, they illustrate the many nized as southeast Asian and native Amer-

ed. Similar, though less complete libros dimensions of trade and tastes then cur- ican surfaced alongside pieces familiar

de exámenes in Seville, Pamplona and rent. More importantly, they allow a view within a European tradition. Similarly,

Valencia archives have also become known. of modest as well as costly jewels which two earrings reportedly from the wreck

But although the drawings endure (and otherwise rarely elude smelting to satiate site of the San Antonio, a Portuguese mer-

could thereafter be copied), few of the cor- demands for gold, while gems met reuse chant ship demolished on Bermuda’s

responding pieces created during the in jewels designed to gratify ever-chang- treacherous reefs in 1621 while carrying

proficiency examinations survive. ing fashion. Absent a knowledge of the some 5,000 pounds of gold and silver from

Other evidences of jewels have come diversity represented among such pieces Cartagena to Cádiz, merge Old and New

forth, however. Even as preparation of now retrieved from the past, Jewels in World motifs (fig. 2). The cartouche-framed

Jewels in Spain 1500–1800 progressed, Spain 1500–1800 admittedly essentially faces crowned with plumes recall the faces/

reports began to emerge of underwater reflects Peninsular wealth and power. masks enclosed in cartouches topped with

explorations whose discoveries included Quintessential among underwater scallop-shell ornament familiar in 16th

jewels lost in disasters at sea. Thus were excavations, are those begun in 1985 of and 17th-century European Mannerist

revealed items (now in the Ulster Muse- the scattered wreckage of Nuestra Señora design. The adaption is suggestive of a

um, Belfast) from the Girona, the Spanish de Atocha, destroyed during a storm near New World origin. Also, the earrings dif-

Armada ship destroyed off the Irish coast the Florida keys while en route to Spain fer from one another in color of gold, the

in 1588 (fig. 1). Wrecksites of “treasure” in 1611. A prodigious wealth of gold was faceted stones, and casting of their upper-

galleons that foundered in Atlantic waters uncovered—ingots, ornamented objects, most sections; where and when they were

on returning to the Peninsula from the devotional and secular jewels, and lengthy made (and copied) may only be determin-

Americas also bared jewels; as did those chains—as well as a plethora of Latin able through scientific analyses.

of ships wrecked in the Pacific while car- American emeralds (selected artifacts An intuitive impression that a curi-

rying principally Asian cargoes from remain in the Mel Fisher Maritime Muse- ous pendant with chain found on an east

Manila to Acapulco. Despite the often bat- um, Key West, Florida). Notably, forms, coast Florida beach in 1962 was Asian

tered or fragmentary condition of artifacts motifs, and craftsmanship soon recog- could be corroborated. When seen in

FI G. 2

FIG. 1 Earrings from the San Antonio. Bermuda, FI G. 3

Cameo from the Girona. Belfast, Ulster National Museum of Bermuda (Incorporating Battered cross from Nuestra Señora

Museum Bermuda Maritime Museum) de la Concepción

FOREWORD

0393viso_006-014#3.indd 7 10/04/12 11:32

FIG. 6

Fray Diego de Ocaña, Nuestra Señora de

Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe) (detail),

1601. Sucre, Cathedral

FIG. 7

Tomás Yepes, Virgen de los Desamparados

(Our Lady of the Forsaken), 1644. Patrimonio

Nacional, Madrid, Convent of Las Descalzas

Reales

a master craftsman and restorer known

to both Vasters and Spitzer, could enter

distinguished public and private collec-

tions as Renaissance jewels. As his casts

(reproduced in Kugel 2000) demonstrate,

André’s source materials included Renais-

sance (or Renaissance-style) jewels as well

as damaged and fragmented pieces pre-

sumably to be restored or created anew

in his workshop.

A contemporary affinity for Span-

ish decorative arts, attested to by the pur-

suits in Spain of baron Jean-Charles Davil-

lier, perhaps gave impetus to André’s

production of pendants replicating those Pilar auction at Zaragoza in 1870, and ings in the Llibres de Passanties that he

of Spain. For Davillier’s collections, exhib- among the illustrations in his Recherches had examined in Barcelona. Although it

ited museum-like in his Paris home, were sur l’orfèvrerie en Espagne au moyen âge cannot now be verified that André him-

known to collectors, including Spitzer. et à la renaissance, published in Paris self traveled to Spain, where he might

Davillier was an active participant in the in 1879, are a number reproducing draw- have gathered jewels that he cast, his work

FOREWORD

10

0393viso_006-014#3.indd 10 10/04/12 11:32

was respected by Spain’s king Alfonso XII, suspension chains like those in André’s

who in 1885, entrusted him with the res- model, is logically believed to have been

toration—masterfully carried out in André’s made in Barcelona in the early seventeenth-

studio—of the venerated reliquary casket century (fig. 10). But even as some pro-

revered in the Escorial monastery since pose that all pendants corresponding to

the late sixteenth century. those shown in the Barcelona Llibres de

With André’s plaster casts known, Passanties were produced in the city (as

doubts I experienced in 1988 on reexam- may have been André’s model), the casts

ining a splendid jeweled and enameled from André’s workshop demonstrate that

pendant shaped as a ferocious and ugly he, at least, could generate copies that

fish (illustrated in Jewels in Spain 1500- might credibly deceive. Still, his recre-

1800 as “late XVI century”) were validated. ations made from conceivably antique

Casts and jewel differ only insignificant- pieces he had at hand could preserve forms

ly (figs. 8 and 9). Clearly, the pendant is otherwise no longer recoverable.

of “Renaissance-style,” if André’s model Restoration also affects identifica-

was perhaps a Renaissance example. (Sev- tion of paintings. Thus, the caption of

eral other fish pendants, including one the portrait titled “Francisco Rizi (?), Count-

in London’s British Museum, closely resem- ess of Fuenrubia,” which signaled my dis-

ble another of André’s casts, evidently inclination to associate the work with

made from an imperfect model perhaps Francisco Rizi (1608–1685), now reads,

in his studio for restoration or replication.) “Unknown Spanish artist, Countess of

André’s casts for a pendant present- Fuenrubia (?)” (fig. 195). For, conservation

ing a cock upon a curving cornucopian work that followed donation of the paint-

base, however, can seem to rely upon a ing to the Hispanic Society in 1990 revealed

design drawn in Barcelona in 1620 (fig. 174), that the inscription lettered on its surface,

which also shows the pendant as with which led to its publication in 1919 as a

cut stones to be set in its base (fig. 11). portrait of the Countess by Rizi, was an

And a similar though less costly enam- easily removed later addition.

eled pendant in the Barcelona Cathedral With newly accessible evidences and

treasury, without gems although with technical resources, questions involving

origins and dating increasingly find reso-

lution—though visual scrutiny first alerts.

FIG. 8 Just as the forty-year interval preced-

Fish pendant, Renaissance style, enameled ing this edition of Jewels in Spain 1500-

gold with emeralds and pendent pearls.

Formerly New York, private collection; present 1800 dictates inclusion of this Preface, so

location unknown does this Preface afford an opportunity

FIG. 9

to express my indebtedness to the many

Cast for fish pendant. Paris, Maison André

FIG. 10

who have shared their knowledge and

Cock pendant, ca. 1620, enameled gold. enthusiasms. Far more numerous than the

Barcelona, Cathedral Treasury

years themselves, I can now only univer-

FIG. 11

Cast for cock pendant. Paris, Maison André sally extend to all my deepest appreciation.

FOREWORD

11

0393viso_006-014#3.indd 11 10/04/12 11:32

FIG. 26

Buckle and mordant design,

ca. 1500, brown ink on paper,

Llibres de Passanties, fol. 7.

Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la

Ciutat de Barcelona

FIG. 27

Buckle and mordant design,

ca. 1500, brown ink over black

chalk on paper, Llibres de

Passanties, fol. 29. Barcelona,

Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de

Barcelona

Isabella to Catherine’s sister, Maria of Por- father, Juan II, in Valladolid in 1453 includ- The design of the pendants which

tugal, in 1500. ed terminal, buckle and six bosses, all of hung from chains or silken ribbons and

Buckles (hebillas), as well as chain gold enameled brownish-gray, green and cords, as of such other jewels as hat orna-

and belt clasps, were often enameled or vermilion; pendent was an enameled ments, continued until late in the fifteenth

jeweled and frequently carried pendants. heart.41 By 1499 however, a hebilla given century within the basically geometric

Patterned buckles and belt ends shown by Isabella to Margarita was itself con- composition of late medieval jewel design.

in two drawings from Barcelona reflect sidered an important jewel (joyel). Of gold Squared, diamonded, triangular, circular,

one type, perhaps intended to be worked with two large pearls, a ruby and point- trefoiled and quatrefoiled, such pendants

in metal alone (figs. 26, 27). 40 One belt ed octagonal diamond, it was designed held but a limited number of gems and

set made by Hans of Ulm for Isabella’s in the form of two serpents.42 occasional mounted or pendent pearls.

FIG. 29 FIG. 30

FIG. 28 Pendant design, ca. 1515, brown ink over black Bartomeu Guaralt, pendant design, 1518,

Pendant, late XV century, jeweled and chalk on paper, Llibres de Passanties, fol. 53. brown ink and ocher wash on paper, Llibres

enameled gold. Formely Barcelona, Cathedral Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de de Passanties, fol. 63. Barcelona, Arxiu

Treasury Barcelona Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

THE REIGN OF FERDINAND AND ISABELLA

24

0393viso_015-034#3.indd 24 10/04/12 11:33

One formerly in the Barcelona Cathedral

treasury (fig. 28), or another in a Hispano-

Flemish border illumination (fig. 23, low-

er right, second from the lower edge), illus-

trate some modification in framework

which had existed earlier almost solely to

support display of gems and pearls, as in

the well-known, non-Hispanic “Three

Brethren” pendant taken by Charles the

Bold at Basel.43 In the years around 1500,

with emphasis to a large extent shifting

from gems to less costly ingredients, the

artistic skills of jewelers were drawn to

the fore as their attention was directed to

exploitation of the adornment potential

of the metal itself and the need or wish

to apply to it all their resources of design

and craftsmanship. Two Barcelona draw-

ings of the second decade of the sixteenth

century (figs. 29, 30) exemplify this focus

on intricate design in the metal.

Crosses, worn pendent at the neck

or suspended from rosaries, were often

gemmed although less valuable materials,

with a marked preference for coral and

enamels, were widely used. During the 1480’s,

Isabella ordered from her jewelers sev-

eral enameled gold crosses, some of gold

with diamonds and rubies and two of

gold-mounted coral.44 In 1483, Vegil made FIG. 31

Juan de Flandes (?), Queen Isabella (detail),

for her a cross with the device of the cru-

ca. 1500, oil on wood. Patrimonio Nacional,

sade, and four years later the platero Fer- Madrid, Royal Palace [inv. 10072266]

nando was assigned the gold necessary

for another cross of the crusade which chain given to Margarita by Ferdinand a tubular gold cross of troncos design

was to have on it a venera, most probably and Isabella; in a second were twenty described in 1503; another in the same

in this instance the scallop-shell emblem.45 diamonds; a third had four large, heart- inventory held nine large corals.48 Rela-

This emblematic cross with venera is seen shaped diamonds and a large pendent tively simple crosses with table-cut stones

in existing portraits of the queen (fig. 31).46 pearl.47 A diamond and pearl cross also and pearls were pictured in contempo-

In 1499, six diamonds, one pointed and hung, as noted previously, from a pearl rary manuscript border illuminations

five table-cut, were set in a gold cross sus- necklace owned by Isabel of Aragon. A (fig. 23); reverses displayed champlevé

pended from a single-turn thin gold mesh sizable sapia (sapphire) was centered in enamels, or niello (fig. 22).

THE REIGN OF FERDINAND AND ISABELLA

25

0393viso_015-034#3.indd 25 10/04/12 11:33

FIG. 39

Hispano-Moresque cassolette, early

XVI century, enameled gold with emeralds

and rubies. New York, Hispanic Society

of America [R3402]

FIG. 40

Moorish ring from Granada, early XVI century,

silver. Paris, Musée du Louvre [OA 3000]

FIG. 38

Moorish necklace from Mondújar (Granada),

XV century, gold. Madrid, Museo Arqueológico

Nacional [inv. 51033]

THE REIGN OF FERDINAND AND ISABELLA

30

0393viso_015-034#3.indd 30 10/04/12 11:33

for her coifs, eighty enameled pieces. One Ornaments designated in Isabella’s they were consistently recorded in even-

set of 102 enameled units was intended for accounts as for the coiffure included gold numbered sets. Isabella bought pairs of

both coif and cap trimming. Sixty small and enameled gold pendants (pinjantes), gold manillas, occasionally enameled, and

and fifty-one large, double-faced Saint Cath- bugle beads (cañutos) of drawn gold (oro in one instance, a single bracelet set with

erine’s wheels, seventy-two wheel-like piec- tyrado) and alfileres, or hairpins, designed diamonds; separately, she ordered enam-

es decorated with fleurs-de-lis and twenty- “para jugar y para tocar,” or to gambol eled hinges for manillas that were to be

four enameled fleurs-de-lis ordered in the about and give finish to the coiffure. Jew- given to her daughter.80 Also in Isabella’s

same years from Barcelona were perhaps eled and enameled headbands (cf. fig. 15) accounts were four enameled filigree gold

for similar use; cinta pendants (jocallos) were also commissioned from Isabella’s axorcas, a brazalete with gold aldabas

with small flowers and counter-enameled jewelers. In 1487, Alzedo created a mod- (knockers, probably bulky charms), manil-

hearts in sets of twenty were also in the el for a headband of enameled gold and las of glass (vidrio) for the infanta and a

Barcelona order, as were seven dozen cinta made for the infanta a band with match- bracelet with enameled clasps and ter-

terminals (cabos).78 The pea-pod and scallop- ing tocadillo, or head covering; two years minals on which Vegil was to place “cer-

shell units ornamenting Catherine of Ara- later, Vallesteros received payment for a tain” pearls.81 Precious stones from a pax

gon’s coif and collar (fig. 25) demonstrate gold headband (tira de cabeza).79 and a piece of gold chain were assigned

application of the quantities of identical Bracelets, listed as ajorcas, manillas to her plateros Vegil and Velasco for use

pieces mentioned in contemporary lists. and brazaletes, were worn in pairs for in bracelets.82 In November, 1500, she

FIG. 41 FIG. 42

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Infanta Maria Ana Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Infanta Ana Mauricia (detail)

(detail), 1607, oil on canvas. Vienna, 1602. Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid, Convent of

Kunsthistorisches Museum [GG–3268] Las Descalzas Reales

THE REIGN OF FERDINAND AND ISABELLA

31

0393viso_015-034#3.indd 31 13/04/12 10:52

now see it as nullified to varying degrees

by stylization), it would appear that reports

of Indian achievements in rendering the

natural rather than actual verity of inter-

pretation provided the impulse. Reflect-

ing criteria of the time in art, those reports

saw lifelikeness, together with ingenuity

and virtuosity, as most desirable qualities.

Understandably, and with excitement,

these qualities were read into aboriginal

art. Emphasis on lifelikeness—as attained

in antiquity or by the aborigine—stimu-

lated the Renaissance craftsman to emu-

lation. But realizing that he must demon-

strate ingenuity and virtuosity as well,

the artist-craftsman, having recourse for the

most part solely within his own frame-

work of artistic experience, availed him-

self, as did Barcelona’s turtle pendant

designer, of patterns developed within an

Old World heritage. Thus the sixteenth-

century Spanish designer who produced

the frog or turtle pendants (figs. 49, 51)

sought not merely to exhibit knowledge

of, and ability to faithfully convey, the

natural, but simultaneously to satisfy

demands for ingenuity and virtuosity in

creating a work of art. He would have

seen in his work not discrepancy between

FIG. 49

Pendant (obverse and reverse), XVI century, actuality and jewel but praiseworthy

enameled gold with rubies and emeralds. enhancement of nature, in itself and with-

Paris, Musée du Louvre [OA 2321]

out the artist’s intervention and modifica-

tion then rarely considered a thing of suf-

may have alerted Europeans to such crea- the turtle shell (fig. 45) were foregone and ficient beauty. Critical analysis of standards

tures as jewels, though again amuletic and may indeed have been imperceptible to of lifelikeness during the Renaissance has

symbolic implications cannot be entirely eyes and minds of Conquest-period chron- examined the dichotomy between present-

140

dismissed, the Peninsular designs are iclers who rendered unqualified praise to day understanding of naturalism and that

totally within the European mode, their naturalism in native jewels. In terms of of the sixteenth-century,141 but a novelist’s

surface patterns dependent upon Euro- the regard in which early sixteenth-cen- lines so well present the matter of chang-

pean tradition. Aboriginal stylizations of tury minds, re-awakened to naturalism ing standards that it does not seem out

the natural conformations of, for example, in art, held it estimable (though one might of place to quote them here:

INTERLUDE: SPAIN AND THE NEW WORLD

42

0393viso_035-046#3.indd 42 10/04/12 11:34

FIG. 50 FI G. 5 1

Coclé pendant (Panama), gold and ivory. New Grabiel Sagui, pendant design, 1596, brown

York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The ink over black chalk on paper, Llibres de

Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Passanties, fol. 327. Barcelona, Arxiu Històric

Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 de la Ciutat de Barcelona

[1979.206.1072]

Four hundred and fifty years ago some been forged by an armourer, as if as a around its cage, puffing and snorting,

entrepreneur or ship’s captain brought change from forging swords, shields, wallowing in the straw and throwing

a rhinoceros to the great city of Nurem- helmets and breastplates he had turned up lumps of dung.142

berg and exhibited it at a fair, where his hand to forging this beast as an

the artist Dürer pushed his way through ornament to the arsenal. It is exactly One sixteenth-century pendant (fig. 52)

the crowd of onlookers, opened his the monster described in the Book of appearing to unite New and Old World

album and started to draw. His draw- Job: “Behold now Behemoth, which I motifs might be thought to illustrate a some-

ing was very precise. There can be no made with thee; he eateth grass as an what different attitude toward New World

mistake: it is a rhinoceros. You can tell ox. Lo now, his strength is in his loins, subject-matter. Hardly the mythological

everything about the animal—its exact and his force is in the navel of his bel- trident-bearing Neptune astride a hippo-

sub-species and even its age. And yet ly. He moveth his tail like a cedar: the campus, the bare-breasted, long-haired,

I repeat (although I cannot fully explain sinews of his stones [sic] are wrapped fully bosomed and skirted female riding

it) that this is not only a real rhinoc- together. His bones are as strong pie- sidesaddle might be regarded, principally

eros—it is also a monstrous, fantastic, ces of brass; his bones are like bars of on the basis of what is possibly a feather

apocalyptic beast. His armour plating iron.” That is how Dürer saw him and headdress, as an American nereid, and the

is curved like the wings of a dragon or drew him. But we, since our childhood, jewel consequently to evidence relation-

a gigantic bat. Drawings of pterodactyls have come to know a completely dif- ship with Spanish maritime activities. Yet

in science fiction novels have wings ferent rhinoceros: ours is just a cum- the circlet closely recalls one worn by Nep-

exactly like that. All the joints are clear- bersome, unwieldy brute, thick-skinned tune in a Barcelona silversmith’s drawing

ly visible, as are the horny claw-like and dirty, with narrow pig-like eyes of 1556, its artist relying upon a Cornelis

toes. The whole creature seems to have and a huge rump. It lumbers clumsily Floris design published by Hieronymous

INTERLUDE: SPAIN AND THE NEW WORLD

43

0393viso_035-046#3.indd 43 10/04/12 11:34

FIG. 83

Ramon Carbo, cross design, 1612, brown

ink over black chalk on paper, Llibres

de Passanties, fol. 395. Barcelona, Arxiu

Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

FIG. 82

Cross, XVI century, enameled gold with

emeralds and pendent pearls. Baltimore,

Walters Art Museum [57.1745]

FIG. 84

Antonio Moro, Maria of Austria (detail), 1551,

oil on canvas. Madrid, Museo Nacional

del Prado [P–2110]

82

years exhibits the cartouche ornamenta- ish court are less profusely ornamented. and 82)242 and with little variation the

tion characteristic of the second half of That worn by Maria of Austria, daughter type continued into the seventeenth cen-

239

the century (fig. 79). The extent to which of Charles V, when she was portrayed tury (fig. 83). Reverses of the gemmed

ingenuity of design in a Mannerist vein in 1551 (fig. 84)241 shows ornament sub- crosses, and obverses of those without

could alter a basically cruciform pendant ordinate to cruciform outline and the stones, exhibited enameled or nielloed

is apparent in a design of but four years stones forming it, though the combina- religious symbols, or decorative designs

later (fig. 80); the Juan Ximénez who exe- tion of gems, pearls and enameled car- (figs. 81, 85, 86).

cuted the drawing was unquestionably touches is characteristic of period inven- The functions of cross and reliquary

acquainted with northern European devel- tories. Another worn by Isabel of Valois were combined in the reliquary cross

opments as comparison of his design with approximately a decade later (fig. 71) has pendant which contained and exhibited

a Matthias Zuendt engraving demon- the form of the cross similarly underlined diminutive relics. Those made for roy-

strates.240 Most pendent crosses in mid- with shaped stones. More than several alty were costly in materials and crafts-

century portraits of members of the Span- basically similar crosses survive (figs. 81 manship, as was a tau cross ordered by

THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY: RENAISSANCE AND MANNERISM

66

0393viso_047-114#3.indd 66 10/04/12 11:37

0393viso_047-114#3.indd 67 10/04/12 12:49

the “architectural” style of later sixteenth-

century jewels.257

Unceasing faith in charms such as

those owned by Juana was shared by all;

Badajoz jewelers in 1589 traded in higas

of ivory and jet.258 The enameled gold

garniture of one rock crystal higa (fig. 110)

may be compared to that in a Barcelona

design of 1580 (fig. 112). Naturalism com-

parable to that of the hand in the design

is best seen, however, in another ivory

and enameled, jeweled gold pendant

(fig. 111), its lightly touching thumb and

index finger elegantly grasping a flower,

FIG. 110 FIG. 111 as in the drawing, or some other valued

Higa, XVI century, rock crystal, enameled gold Pendant, XVI century, ivory and enameled gold.

offering.259

and rubies. Madrid, Fundación Lázaro London, The British Museum [1941, 1007.1]

Galdiano [inv. 3265] Also of semi-precious stones—pre-

dominantly green, but also carnelian—

were miniature ship and gourd pendants

with pendent pearls or pearl clusters, some

garnished with plain and with filigree

gold inventoried in 1560.260 Cortés report-

edly carried two ship pendants wholly

of emeralds in a cloth (servilleta) at his

belt, while a ship upon a leafy gold branch

ornamented a presiding official’s helmet

during tournaments celebrating the mar-

riage of the duke of Savoy and Catalina

Micaela in 1585.261 That worn upon the

helmet perhaps functioned, as had the

enseña, as an emblematic device suggest-

ing restraint and wise judgment as in

Covarrubias Orozco’s Emblemas morales,

or virtue and hoped-for security as in

Alciati.262 Though surviving ship pendants

FIG. 112 FIG. 113

Pera Estivill, pendant design, 1580, brown Magi Sunier, pendant design, 1594, brown are most often considered to be of Italian

ink over black chalk on paper, Llibres ink on paper, Llibres de Passanties, fol. 319. (particularly Venetian) or German origin,

de Passanties, fol. 289. Barcelona, Arxiu Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat

Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona de Barcelona many were documented in sixteenth-

century Spain; one relatively simple in

design was drawn in Barcelona in 1594

(fig. 113).263

THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY: RENAISSANCE AND MANNERISM

76

0393viso_047-114#3.indd 76 10/04/12 11:39

Larger, more important individual

pendant jewels were of shapes found also

among the diminutive brincos. Book-shaped

pendants hung not only from rosaries

and strings of olivetas but were worn sus-

pended at the neck; a gold gargantilla

in 1589 had as its pendant a twenty-piece

gold librito.264 During the eighties, the

miniature volumes were awarded as tour-

nament prizes.265 They occasionally enclosed

portraits, Isabel of Valois giving one of

black-enameled gold with portraits of her

parents, the king and queen of France,

to her daughter, the infanta Catalina.266

As with most jewels long in favor, enam-

eled gold book pendants exhibited con-

temporary ornamentation. One of them

(fig. 55) incorporates strapwork decora-

tion possibly of mid-century though its

central cartouche offers an element repeat-

ed in the design of a librito pendant drawn

in 1616 (fig. 114). Another design of the

early sixteenth century displayed a sur-

face of botanical motifs (fig. 116) while

one of 1613 employed cord-like Moresque

ornamentation (fig. 115).

114

FIG. 114

Ioseph Iordan, pendant design, 1616, brown

ink on paper, Llibres de Passanties, fol. 410.

Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat

de Barcelona

FIG. 115

Mateu Torent, pendant design, 1613, brown

ink on paper, Llibres de Passanties, fol. 401.

Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat

de Barcelona

FIG. 116

Pendant design, ca. 1520, brown ink on paper,

Llibres de Passanties, fol. 69. Barcelona, Arxiu

Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

115 116

THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY: RENAISSANCE AND MANNERISM

77

0393viso_047-114#3.indd 77 10/04/12 11:39

and the sword at the right—that of Jus-

tice—the severity of punishment meted

out to the unrepentant; on the reverse is

the cross of Saint Dominic in black and

white enamels.445 The unadorned form

of the cross of Saint Dominic, the insig-

nia of the Order of the Militia of Christ,

as drawn for example in 1630 (fig. 201),

was inalterable, though ornament was

otherwise modified, as has been noted,

to satisfy contemporary tastes. Thus an

order designed in 1575 was bordered with

cartouche and vegetal forms (fig. 202)

FIG. 200

while that of circa 1700 was enclosed in

Badge of the Holy Order of the Inquisition

(obverse and reverse), ca. 1700, enameled gold gem-studded, curving leaves of carved

with rubies and emeralds. Formerly London,

gold (fig. 200).

Cameo Corner; present location unknown

Indispensable to members of reli-

gious orders, congregations and confra-

In the Instituto de Valencia de Don of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ternities, veneras (or hábitos and encomien-

Juan is a small oval pendant somewhat (fig. 200), the central green cross on its das in seventeenth-century documents),446

like that seen in the Pastrana portrait with obverse representing the hope of repen- were widely used, thus offering a view of

superimposed enameled floriated cross tance before punishment and the salva- changing attitudes toward jewel design.

of the reverse of Inquisition veneras fit- tion granted on recognition of Christ, the Multiplication of the confraternities, neces-

ted to the rounded oval surface. A some- olive branch at the left symbolizing peace sitating enaction of governing canonical

what later pendant bears the insignia and clemency offered to the repentant, law under Clement VIII in 1604, coincided

FIG. 203

FIG. 201 FIG. 202 Ramon Daura, design for Order of the Knights

Pere Aguilera the Younger, design for Order of Geronim Jener, design for an order, 1575, of St. John, 1641, brown ink over black chalk

the Militia of Christ, 1630, brown ink on paper, brown ink on paper, Llibres de Passanties, on paper, Llibres de Passanties, fol. 502.

Llibres de Passanties, fol. 464. Barcelona, fol. 241. Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat

Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona de Barcelona de Barcelona

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

124

0393viso_115-152#3.indd 124 10/04/12 12:07

FIG. 204

Pera Pau Garba, pendant design, 1617, brown

ink on paper, Llibres de Passanties, fol. 413.

Barcelona, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat

de Barcelona

FIG. 205

Pendant (reverse), XVII century, enameled gold

with gems. Madrid, Instituto de Valencia

de Don Juan

FIG. 206

Pendant, XVII century, enameled gold with

diamonds. Greenwich, London, Ranger’s

House

chronologically in Spain with the years

in which restrictions severely limited per-

missible jewel types. The jewel designer

therefore turned much of his attention to

the veneras required by all members of

truly organic cofradías, who during all

confraternity-related functions wore the

scapulary, medalla, hábito and cordón

bestowed on admission. From shortly

after 1600 until the late twenties, pendants

religious in association were a primary

consideration, as is shown by reference

to the designs submitted by Barcelona’s

guild examinees. Maltese cross pendants

appear among the drawings intermittent-

ly from 1602 until the mid-forties (fig. 203).447

Two of the four jewel designs of 1617 intro-

duce a pendant of inverted triangle outline

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

125

0393viso_115-152#3.indd 125 10/04/12 12:07

FIG. 261

Giuseppe Gricci, porcelain wall panel (detail),

ca. 1760–65. Patrimonio Nacional, Aranjuez,

Royal Palace, Porcelain Cabinet

FIG. 260

Francisco de Goya, Francisca Vicenta Chollet

y Caballero (detail), 1806, oil on canvas.

Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum

[M.1981.7.P]

set upon flowered branches was by the Oriental figure familiar to the court since temporary jeweler’s drawing offers a detailed

mid-seventies a customary gift among the the mid-sixties in chinoiserie porcelain rendering of the arrow-shaped ornaments

nobility, often given to a bride by her rel- decorations in the Aranjuez Palace (fig. 261). (fig. 263), the unadorned center section to

atives,555 and the hair ornament increased A large and magnificent branch (ramo) receive a securing jeweled comb as shown

in size, value and importance. In 1777, of brilliants and emeralds given to Maria in the portraits of Maria Luisa and her

the duchess of Alba inherited a large pio- Luisa of Parma by Charles IV was perhaps daughter. In 1802, as Maria Luisa quickly

cha of brilliants with a butterfly of rose- similarly worn, though the best known took possession of the recently deceased

colored diamonds, a sapphire and a ruby; of her hair ornaments is the arrow of bril- duchess of Alba’s jewels, it was perhaps

another of diamonds, including three yel- liants with which she was most often por- for such use that she selected a tortoise-

low in hue, went to her mother.556 A dec- trayed, or caricatured (figs. 262 and 264); shell peineta, or ornamental comb, with

orative extreme to which the floral hair one was given to her by her lover, the teeth of gold and central ornament exe-

ornament of brilliants could be carried is prime minister Godoy, in October 1800.557 cuted in brilliant-trimmed blue enamel.559

seen in Goya’s portrait of Francisca Vicen- The motif was hardly unique, for her Brooches (alfileres) were not always

ta Chollet y Caballero (fig. 260). In gen- daughter wore a similar jewel (fig. 264) specified in inventories as for the hair or

eral outline and manner of placement on and the queen’s rival, the duchess of Alba, for the dress and may have been worn

the coiffure, the spray seen in the portrait owned enameled gold arrow-shaped alfileres, interchangeably.560 Thus a delicate floral

is not entirely unlike that adorning an some designated as for the hair.558 A con- spray shown by a Barcelona examinee

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

158

0393viso_153-177#2.indd 158 10/04/12 12:58

262

263

FIG. 262

Francisco de Goya, Time and the Old Women

(detail), ca. 1810–12, oil on canvas. Lille,

Musée des Beaux Arts [P 50]

FIG. 263

Coiffure ornament designs, ca. 1800,

watercolor and black ink on paper. Madrid,

Biblioteca Nacional [DIB/14/29/2]

FIG. 264

Francisco de Goya, The Family of Charles IV

(detail), 1800, oil on canvas. Madrid, Museo

Nacional del Prado [P–723]

264

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

159

0393viso_153-177#2.indd 159 10/04/12 12:18

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Medieval Textiles in the Cathedral of Uppsala, SwedenDe la EverandMedieval Textiles in the Cathedral of Uppsala, SwedenEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- Boucher 001Document31 paginiBoucher 001gismatronÎncă nu există evaluări

- Centres and Peripheries in European Jewellery - From Antiquity To The 21st Century PDFDocument316 paginiCentres and Peripheries in European Jewellery - From Antiquity To The 21st Century PDFjosesbaptista100% (1)

- Jewelery Research PaperDocument5 paginiJewelery Research Paperapi-317113210Încă nu există evaluări

- Rogers Jewelers Summer 2009 CatalogDocument32 paginiRogers Jewelers Summer 2009 CatalogSteve Kirklin100% (1)

- Catalogue of A Collection of Continental Porcelain Lent and DescribedDocument160 paginiCatalogue of A Collection of Continental Porcelain Lent and DescribedPuiu Vasile ChiojdoiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shrubsole Rococo E-CatalogDocument23 paginiShrubsole Rococo E-CatalogBenjamin Miller100% (4)

- Dupuis Fall 2014 Jewels Auction by DupuisAuctions (Fall - 2014.pdf) (194 Pages) PDFDocument194 paginiDupuis Fall 2014 Jewels Auction by DupuisAuctions (Fall - 2014.pdf) (194 Pages) PDFdoveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trademarks On Base-Metal Tableware PDFDocument347 paginiTrademarks On Base-Metal Tableware PDFobericaaa100% (1)

- Discovery Featuring Estate Jewelry & Silver and Textiles & Couture - Skinner Auction 2551MDocument72 paginiDiscovery Featuring Estate Jewelry & Silver and Textiles & Couture - Skinner Auction 2551MSkinnerAuctions0% (1)

- Ancient Greek JewelryDocument67 paginiAncient Greek JewelryIshtar AmalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fine Jewelry Auction - SkinnerDocument124 paginiFine Jewelry Auction - SkinnerSkinnerAuctions100% (4)

- Premier Catalog 2010 2011Document112 paginiPremier Catalog 2010 2011Kaity Morris100% (2)

- Royal Faberge PDFDocument273 paginiRoyal Faberge PDFMarian Sisu100% (2)

- Spring 2017 Gems Gemology v2 PDFDocument145 paginiSpring 2017 Gems Gemology v2 PDFJORGE LUIS HERNANDEZ DUARTEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vicenza: Apex of The Jewellery PyramidDocument6 paginiVicenza: Apex of The Jewellery PyramidShalini Seth100% (1)

- Fashion Capitals of The WorldDocument28 paginiFashion Capitals of The Worldshubhangi garg100% (1)

- By Zantin 00 DoddDocument318 paginiBy Zantin 00 DoddAndrei CosminÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art Deco JewelryDocument2 paginiArt Deco JewelrychrissypbshowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gold The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin V 31 No 2 Winter 1972 1973Document56 paginiGold The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin V 31 No 2 Winter 1972 1973luizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Textile Museum of CanadaDocument10 paginiThe Textile Museum of CanadaJinno MagbanuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fine Jewelry - Skinner Auction 2529BDocument148 paginiFine Jewelry - Skinner Auction 2529BSkinnerAuctions100% (6)

- Victorian Jewellery (1837 - 1900)Document10 paginiVictorian Jewellery (1837 - 1900)Dr. Neeru jain100% (3)

- European Furniture & Decorative Arts Featuring Silver - Skinner Auction 2542BDocument148 paginiEuropean Furniture & Decorative Arts Featuring Silver - Skinner Auction 2542BSkinnerAuctions100% (1)

- Current Trends in JewelleryDocument8 paginiCurrent Trends in Jewelleryreetika guptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Wittelsbach Blue Auction CatalogueDocument23 paginiThe Wittelsbach Blue Auction Cataloguehbraga_sruival100% (2)

- Temporary JewelleryDocument9 paginiTemporary JewelleryKim JohansenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Treasures of The National Museum of SloveniaDocument2 paginiThe Treasures of The National Museum of SloveniaSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesÎncă nu există evaluări

- By Guy de Maupassant: Prepared By: Loren Haramae M. Alcordo BAMM - 303Document32 paginiBy Guy de Maupassant: Prepared By: Loren Haramae M. Alcordo BAMM - 303Johanne May Capitulo LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elements Catalog Jan 2013Document92 paginiElements Catalog Jan 2013Joe UnanderÎncă nu există evaluări

- 16th Century JewelryDocument161 pagini16th Century JewelrycattieeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The History of JewelleryDocument4 paginiThe History of Jewelleryapi-31812472100% (1)

- GemsDocument80 paginiGemssaopauloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antique Jewelry An 001080 MBPDocument516 paginiAntique Jewelry An 001080 MBPgiselin_aaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discovery Featuring Estate Jewelry & Silver and Textiles & Couture - Skinner Auction 2602MDocument68 paginiDiscovery Featuring Estate Jewelry & Silver and Textiles & Couture - Skinner Auction 2602MSkinnerAuctions100% (1)

- Project01 JewelryDocument2 paginiProject01 JewelryK.n.TingÎncă nu există evaluări

- FiligreeDocument4 paginiFiligreeszita2000Încă nu există evaluări

- European Furniture & Decorative Arts Featuring Fine Silver and Souvenirs of The Grand Tour - Skinner Auction 2715BDocument132 paginiEuropean Furniture & Decorative Arts Featuring Fine Silver and Souvenirs of The Grand Tour - Skinner Auction 2715BSkinnerAuctions100% (2)

- AftDocument7 paginiAftYerik LaloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jewellery HistoryDocument16 paginiJewellery Historyjosesbaptista100% (1)

- The Bulgari Blue CatalogueDocument28 paginiThe Bulgari Blue Cataloguehbraga_sruivalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jewellery PortfolioDocument22 paginiJewellery PortfolioSwarnima DwivediÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seidman 2006 Ch7 Interviewing As A RelationshipDocument9 paginiSeidman 2006 Ch7 Interviewing As A RelationshipfarumasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fine Jewelry - Skinner Auction 2693BDocument236 paginiFine Jewelry - Skinner Auction 2693BSkinnerAuctions83% (6)

- English Jewellery 00 Evan U of TDocument276 paginiEnglish Jewellery 00 Evan U of Tlulu100% (3)

- Art Nouveau-Siegfried BingDocument2 paginiArt Nouveau-Siegfried Bingesteban5656Încă nu există evaluări

- Georgian Embroidery and Textiles CollectionDocument2 paginiGeorgian Embroidery and Textiles CollectionGeorgian National MuseumÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Jewellers - Hazoorilal JewellersDocument84 paginiInternational Jewellers - Hazoorilal JewellersShilpi Kapoor100% (1)

- Italian Fashion History of The 14th and 15th Century PDFDocument37 paginiItalian Fashion History of The 14th and 15th Century PDFAna Maria NegrilăÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rings On Their Fingers:: Ring Wearing From Ancient Times To The RenaissanceDocument8 paginiRings On Their Fingers:: Ring Wearing From Ancient Times To The RenaissancerazanymÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2626B ModernDocument188 pagini2626B ModernSkinnerAuctions100% (4)

- BBLB Venetian Glass GlossaryDocument7 paginiBBLB Venetian Glass GlossaryNaadirah JalilahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Near Eastern Jewelry A Picture PDFDocument32 paginiNear Eastern Jewelry A Picture PDFElena CostacheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Skinner Fine Jewelry Auction 2471Document121 paginiSkinner Fine Jewelry Auction 2471SkinnerAuctions100% (3)

- SP12Document92 paginiSP12saopauloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Holiday Auction Featuring Estate Jewelry & Silver and Textiles & Couture - Skinner Auction 2576MDocument76 paginiHoliday Auction Featuring Estate Jewelry & Silver and Textiles & Couture - Skinner Auction 2576MSkinnerAuctions0% (1)

- Gems&Gemology: Winter 1991Document81 paginiGems&Gemology: Winter 1991saopaulo100% (1)

- Chaffers' Hand Book to Hall Marks on Gold and Silver PlateDe la EverandChaffers' Hand Book to Hall Marks on Gold and Silver PlateÎncă nu există evaluări

- FuturismDocument25 paginiFuturismNatalie RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visible Spirit - BerniniDocument1.548 paginiVisible Spirit - Berniniebooksfree67688% (17)

- At Home in The Heartland - Elizabethtown, KentuckyDocument59 paginiAt Home in The Heartland - Elizabethtown, KentuckyMountainWorkshopsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coinage in Ancient Greece by The NickleDocument56 paginiCoinage in Ancient Greece by The NicklechrysÎncă nu există evaluări

- CỦNG CỐ BÀI TẬP-TỪ VỰNG-UNIT 1-TRUNG TÂM-9A2Document9 paginiCỦNG CỐ BÀI TẬP-TỪ VỰNG-UNIT 1-TRUNG TÂM-9A2BruhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flea Guide FINALDocument21 paginiFlea Guide FINALWill PriceÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hellenistic Fringe - The Case of MeroëDocument21 paginiThe Hellenistic Fringe - The Case of MeroëMarius JurcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quarter 3, Wk.2 - Module 2: Artists From Neoclassical and Romantic PeriodsDocument19 paginiQuarter 3, Wk.2 - Module 2: Artists From Neoclassical and Romantic PeriodsMa Ria LizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talbot, Alice-Mary, The Restoration of Constantinople, PDFDocument20 paginiTalbot, Alice-Mary, The Restoration of Constantinople, PDFGonza CordeiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grube, Ernst J. - The Art of Islamic Pottery (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, V.23, No.6, February 1965)Document20 paginiGrube, Ernst J. - The Art of Islamic Pottery (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, V.23, No.6, February 1965)BubišarbiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geometric Style: Iliad and The Odyssey But The Visual Art of This PeriodDocument23 paginiGeometric Style: Iliad and The Odyssey But The Visual Art of This Periodaudreypillow100% (1)

- Frame 78 PDFDocument3 paginiFrame 78 PDFAltypreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art AppreciationDocument12 paginiArt AppreciationJoanna Marie MaglangitÎncă nu există evaluări

- The ABC of Indian ArtDocument378 paginiThe ABC of Indian ArtRohitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gerard SekotoDocument3 paginiGerard Sekotoapi-169900588Încă nu există evaluări

- Pe 8Document12 paginiPe 8Aika Kate KuizonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Craft and Creative Media Mosaic Power Point Chap 7Document7 paginiCraft and Creative Media Mosaic Power Point Chap 7Sarah Lyn White-CantuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and TajikistanDocument39 paginiArts in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and TajikistanJoshua Poblete DirectoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Bahasa InggrisDocument6 paginiTugas Bahasa InggrisBaitul AtiqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chakra Purse: Designed by Kim RutledgeDocument4 paginiChakra Purse: Designed by Kim RutledgeWendy Balacano SalamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hades: Cornucopiae, Fertility, and Death by Diana BurtonDocument7 paginiHades: Cornucopiae, Fertility, and Death by Diana BurtonJoe MagilÎncă nu există evaluări

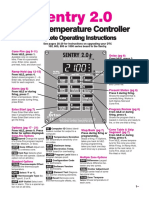

- Manual Horno Sentry 2.0 PDFDocument32 paginiManual Horno Sentry 2.0 PDFJose BacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Borobudur Temple Compounds (Indonesia) © UNESCODocument34 paginiBorobudur Temple Compounds (Indonesia) © UNESCOliuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14 Traditional Japanese Towns That Still Feel Like They're in The Edo PeriodDocument1 pagină14 Traditional Japanese Towns That Still Feel Like They're in The Edo PeriodWan Mohamed Azrin Che Wan ShamsiruddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ching V SalinasDocument2 paginiChing V SalinasCharlotteÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Cultural History of Work in Antiquity PDFDocument8 paginiA Cultural History of Work in Antiquity PDFtarek elagamyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marble AssignmentDocument8 paginiMarble AssignmentRahul RanganathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Now: in L) Rivate LastDocument1 paginăThe Now: in L) Rivate LastreacharunkÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA-13 Aggarwal Builder (Crest II - Building Work)Document19 paginiRA-13 Aggarwal Builder (Crest II - Building Work)AmitRanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Korea Lonely Planet SeoulDocument55 paginiKorea Lonely Planet SeoulAmanda PattersonÎncă nu există evaluări