Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Fraser - Reponse To

Încărcat de

Hélio Alexandre Da SilvaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Fraser - Reponse To

Încărcat de

Hélio Alexandre Da SilvaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Reply to Zylan

Author(s): Nancy Fraser

Source: Signs, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Winter, 1996), pp. 531-536

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3175087 .

Accessed: 12/06/2013 14:57

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 143.106.1.138 on Wed, 12 Jun 2013 14:57:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Replyto Zylan

Nancy Fraser

5Y TVONNE

in

ZYLAN CLAIMS

and Linda Gordon's

to identifysome weaknesses

my (1994) essayon dependencyand to

trace themto our genealogicalmethod.Her commentraises

both theoreticalissues and issues of historicalinterpretation,

while proposinga relationbetweenthem.In what follows,I shall focus

on the theoreticalissues. I hope to show thatour approach is conceptu-

ally sound, productiveof insight,and politicallyuseful.

Two of Zylan's theoreticalclaims are of particularinterest:first,that

our approach obscuresagencyand, second, thatwe do not adequately

specifyhow discoursesrelateto institutions. The firstof theseclaims I

considermistakenand confused.The second, in contrast,raises serious

issues, but these are not satisfactorilyresolvedby the approach Zylan

recommends.In bothcases, I shallsuggest,she failsto givedue weightto

the discursivelymediatedcharacterof social life.

Let me begin with the question of agency.Accordingto Zylan, our

analysisis "pervadedby genealogy'sskepticismabout prediscursive sub-

and purposiveaction."We are said to "displaya Foucaul-

jects,interests,

dian cynicismabout the power of individualactors" and to underplay

"intentionaldeployments"and "conscious deliberatearticulations"of

keywords,as well as the "strategicchoices of actors."

Such complaintsare found in many discussionsof genealogy,post-

structuralism,and Foucault.Buttheyare nevertheless misplaced.To ana-

lyze culturalcomplexesof meaning,such as those surroundingthe term

dependencyin theUnitedStates,is not to denythatindividualsact con-

sciously,deliberately,and strategically,nor that theysometimesdeploy

such termsinstrumentally to promotetheirown interestsand goals. It is,

rather,to make available forpoliticalcritiquethenetworkof meanings,

assumptions,and imagesthatconstitutethebackgroundand the stuffof

intentionalaction. Far fromrepresenting a threatto agency,then,an

analysissuch as ours helpsexplainhow it is possiblewhileextendingthe

reach of critique.

To understandwhy,recall that human actions,as opposed to mere

behaviors,always occur under descriptions.The goals, intentions,and

[Signs:Journalof Womenin Cultureand Society1996, vol. 21, no. 2]

? 1996 byNancyFraser.All rightsreserved.

Winter 1996 SIGNS 531

This content downloaded from 143.106.1.138 on Wed, 12 Jun 2013 14:57:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fraser REPLY

intereststhatare constitutive of social actionare discursively structured,

evenwhenthesignifications remaintacit.The same is trueof everyother

elementand conditionof social action, includingthe actor's personal

identityand collectiveidentifications, her (and others') implicitdefini-

tion(s) of theaction situation,thenormsgoverningthesocial practice(s)

thatmake heractionwhat it is, and thejustificatory rationalesshe might

advance if and when it is challenged.No action, indeed no essential

elementof action, is simplygiven prediscursively. All are irreducibly

interpretative,shot throughwithsignification.

Yet agentsdo not createthesemeaningsex nihilo.Theydraw,rather,

on a historicallyspecificstock of culturallyavailable significations.The

latterdo not,however,come in discreteatomisticbits,but in structured

"webs of significance," "interpretative horizons,"or "discursiveframes,"

to use the lingo of Quineans, hermeneuticists, and poststructuralists,

respectively. These framesare historicallysedimented,oftenmutually

contradictory, and unevenlyentrenched acrosssocial space. The Foucaul-

dian insight-sharedby Raymond Williams-is to view themas power-

laden, provisional stabilizations of previous contests and negotiations,

which in turnpresupposedpriordiscursiveframes.'Qua interpretative

gridsand logics of possibility, such framesare a necessaryconditionof

human agency.Far fromrenderingit impossible,then,theyprovidethe

indispensablesignifying stuffout of which intentionalsocial action is

made.

ContraZylan,moreover,social actionis usuallybothunreflective and

intentional.Actorsgenerallystandin an unreflective relationto the dis-

cursive framesthat enable theiragency.Althoughtheyknow how to

draw on theseframesin practice,theytypicallylack reflective awareness

of the networkof tacitassumptions,connotations,and imagestheirac-

tionsmobilize.As a result,theirintentionalactionsoccuragainsta doxic,

commonsensebackgroundof taken-for-granted beliefthatescapes criti-

cal scrutiny.When such beliefworks,as it generallydoes, in theinterests

of the powerful,it can subvertthe intentionsof less powerfulactors.

My and Gordon's articlecited several cases where intentionalbut

unreflective action yieldedunintendedconsequencesin contextsof in-

equality.One was thefailedattemptof late nineteenth-century reformers

to destigmatizerecipientsof aid by designatingthemas dependentsin-

stead of paupers. Anotherwas the successfulattemptof radical white

workingmento claim civil and politicalrightsby recastingthe meaning

of wage labor as conferringindependence.Zylan's discussionof this

1ForreasonsI havearguedelsewhere,

thisquasi-Foucauldian

conceptionis superior

to somealternatives, theLacanianviewof"thesymbolic

including order."See Fraser

1992,1994b.

532 SIGNS Winter 1996

This content downloaded from 143.106.1.138 on Wed, 12 Jun 2013 14:57:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REPLY Fraser

second case muddiesthe waters.She arrivesby a circuitousrouteat the

view statedstraightforwardly in our essay: througha seriesof struggles

radicalworkingmenthemselvesconstructedtheideal of thefamilywage.

We in no way deniedtheiragencywhen we noted its unintendedconse-

quence: the "independence"theyachievedthroughthismeanseffectively

veiled theireconomic subordinationas wage laborers.The analogy we

drew to the povertyline concernedthe result,not the agency,of the

redefinition:in both cases inequalitywas coveredover. Finally,yet an-

otherexample invokedby Zylan has also been discussedelsewhereby

me: namely,the effortsof twentieth-century social workersto enhance

theirown professionalstatusby stressingthe "dependency"of theircli-

ents (Fraser 1996). In all thesecases, actors' lack of reflectivenesscon-

cerningthe ideological baggage carriedby theirdiscourseled to unin-

tendedconsequencesof intentionalaction in contextsof unequal power.

The pointis crucialforunderstanding thepoliticalintentof our essay.

As Zylan herselfnotes,we soughtto demystify theideologysurrounding

today's discourseof welfaredependency.Our aim was not to deny or

downplayagencybut,rather,to interrogate the discursivematerialsout

of whichit is made. By promotingincreasedreflectiveness on thedoxa of

welfare,we hoped preciselyto enhancethe potentialforefficacious,in-

tentional,oppositionalagency.

Our strategy, once again, was to reconstruct the genealogyof depen-

dency. We sought to make explicit-and hence criticizable-the current

hegemonic postindustrial discursive frame by contrasting it to two

distinct-preindustrial and of

industrial-systems understandings that

informedpriorhistoricalusages of dependency.The core of our project

was to identifythe threeframesand to analyze theirrespectiveconcep-

tual structures.Althoughwe took pains to situatethediscursiveshiftsin

relationto large-scaleinstitutionaland social-structuralshifts,we did not

seek to account forthemcausally.Zylan insinuatesthat,absent causal

explanations,our approach is underdevelopedand flawed. What she

presentsas a missing"required"componentof our project,however,is

actuallyanotherlevel of analysis-a complement,not a rival,to ours.

Zylan misses,moreover,thecontribution our workcan make to more

traditionalscholarship.Because we identifieda hegemoniccomplex of

significationsthatare in play even when not explicitlynoticedby social

actors,our analysisshould be usefulto scholars,like her,who seek to

explain particularhistoricaloccurrences.It makes available forcritical

analysisand explanatoryuse a dimensionthatis too oftenneglected:the

cultural framesthat mediate actors' experienceof, and responses to,

social problems.Far frominhibitingmore familiarmodes of historical

and social-scientific

inquiry,then,we offerthema valuable resource,one

thatcan deepen the criticaldimensionof theirwork.

Winter 1996 SIGNS 533

This content downloaded from 143.106.1.138 on Wed, 12 Jun 2013 14:57:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fraser REPLY

Zylan, unfortunately, seemsunwillingto make use of thisresource.To

be sure, she claims to accept a "conceptionof the constructionof dis-

course [that]is notradicallydifferent fromthatofferedby [us]." And she

says, in addition, that she is indebted to myworkon thepoliticsof need

interpretation. Yet the model she proposes is objectivistic.It treatsdis-

cursiveconstructions as effects to be explainedbyreference to "structures

of politicalopportunity," themselvesconceivedas extradiscursive. "Cre-

ated at theintersection of institutional development, demographicshifts,

and strategicpoliticalaction,"these"structures" are said to explainwhen

and whycertainkeywordsemergeand become salient.In fact,the "ex-

planation" closes offmanyof the criticalquestionsthatwere painstak-

inglyopened up by our genealogyof dependency.

ConsiderZylan's account of the emergenceof the discourseof "wel-

faredependency":"demographicchanges,fiscalburdens,and racial and

gender politics combined to create a structureof opportunitywithin

whichpolicymakers'and social workers'rhetorics... could be deployed

and take root." The claim here is that ADC, previouslya respectable,

unstigmatizing programof incomesupportforsinglemothersand their

children,suddenlycame underattackin the 1950s because of "changing

demographicsof theprogram'srecipients"-namely, a risein thepropor-

tion of black claimants-and "rapidlyexpanding"ADC expenditures

that were "in many cases eatingup a largerand largerportionof a state's

totalexpenditures."Also contributing to thisoutcomewerethe"strategic

interests"of whiteSouthernpoliticiansseekingto ensurean "adequate

supply"of domesticand agriculturallabor and the failureof organized

labor,middle-classwomen'sorganizations,and social workersto mount

a defenseof theprogram.As a resultof this"politicalopportunity struc-

a

ture,"Zylan claims, stigmatizing new discourse of welfare dependency

emergedto justifythe impositionby the statesof new,punitiverulesin

the implementation of the program.

What is strikingabout this account is the absence of any cultural

contextthatcould explain why and how social actorsshould construct

these"changingdemographics"and "institutional developments"as war-

ranting attacks on "welfare dependency." Zylan writes as ifsuch attacks

wereself-evidently appropriateresponsesto increasedblackparticipation

and increasedstateexpendituresforADC. This, however,begs the cru-

cial questions.The same period from1935 to the 1950s also saw big

increasesin black participationin social insuranceprograms;yetthere

was no comparable stigmatizationof theserecipientsas "dependents."

Likewise,the same periodwitnessedsteeprisesin stateexpendituresfor

programsto subsidizefarmersand businesses,but thesedid not provoke

outcriesagainstdependency,nor calls forsexual monitoringof the ben-

eficiaries.

534 SIGNS Winter 1996

This content downloaded from 143.106.1.138 on Wed, 12 Jun 2013 14:57:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REPLY Fraser

The point,then,is thatchangingdemographicsand institutional de-

velopments do not of themselves explain anything. In order to have any

historicaleffects,these conditionsmust firstbe noticed,experienced,

interpreted, and respondedto by social actors,both individualand col-

lective.Theymust,in otherwords,be culturallymediatedand appropri-

ated. In the same way,actors' strategicinterests, identities,and identifi-

cations are not objectivelygiven but must be culturallyconstructed.

"Explanations"thatfailto unpackthediscursiveprocessesbywhichthis

occurs serveto naturalizehegemonicinterpretations. By lendingthose

interpretations an aura of self-evidence, theysimultaneouslyimmunize

themagainstcritique.

In fact,industrial-era understandings of dependency, as detailedin our

essay,help supplythe missingmediations.Not only was that category

alreadyfeminized,racialized,and individualizedin the cultureat large

but itsmeaningswere also encoded in a two-tiersocial-welfarestructure

thatleftADC claimants,butnot social insuranceclaimants,vulnerableto

the discretionof caseworkers,administrators, and state legislatures.I

leave it to the historiansto determineexactly when and where such

discretionwas exercisedin itsmostpunitiveand racistforms.Butthefact

remainsthat the 1935 Social SecurityAct createdADC as a program

whose implementation was subjectto considerablelocal discretionand

latitude.It therebyincorporatedthe long-standing view,traceableback

through mothers' pensions and to

beyond friendlyvisiting,that solo

mothersdid not have an unconditionalentitlement to aid, that their

deservingness had to be vetted on a case-by-casebasis, that careful

screening and close personalsupervisionwerenot in principleincompat-

ible with theirrightsas citizens,that-in short-they were dependents

walkinga fineline between"good" and "bad" dependency.2

The imperativeof policingthatlinewas builtintothedesignof ADC.

But withthe gradual emergenceof a postindustrialsocioculturalorder,

"good" dependencybecame harderto find.Withthe decenteringof the

family-wageideal, women's economic dependencywithinmarriagebe-

came contestedand could no longerserveas a positivecounterweight to

thenegativeconnotationsofpublicaid. Atthesame time,moreover,with

the dismantlingof racistand sexist sociolegal dependency,the already

tenuousU.S. sense of dependencyas a structuralrelationof subordina-

tionwas further obscuredand theterm'svictim-blaming, individualizing

connotationswere heightened.The upshot was a socioculturalconstel-

lationin which"welfaredependency"could appear as a problem.The set

of overlappingunderstandings surrounding this"problem"mediatedac-

tors' constructionsof theiridentities,interests, and politicalstrategies.

2 For historical

evidence,see Gordon 1994.

Winter 1996 SIGNS 535

This content downloaded from 143.106.1.138 on Wed, 12 Jun 2013 14:57:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fraser REPLY

This analysisopens thepossibilityof a deeper,morecriticaltakeon the

eventsdiscussedbyZylan,includingthedeclineofmaternalist politicsand

theabsenceof supportforADC. Had Zylan beenless intenton distancing

herselffromour genealogicalmethod,she could have availedherselfof its

fruitsto understandtheculturallensesthroughwhichactorsrespondedto

thedevelopments she describesbydemonizing"welfaredependency." Fail-

ingto do so, sheleavesunscrutinized a setofassumptionsand understand-

ingsthatoughtnot to be allowed to go withoutsaying.

Thereis an urgentneedto keepsightof thispointtoday.Once again,a

panic about "welfaredependency"appearsas theself-evidently appropri-

ate responseto a social crisisconstructedin termsof "thebudgetdeficit,"

"runaway expenditureson entitlements," "skyrocketing caseloads," "a

teen pregnancyepidemic,""changingracial demographics,""the under-

class," and the "declineof familyvalues." In thissituation,criticalintel-

lectualswho wantto join thestruggle fora justand humanesocietycan do

any numberof politicallyusefulthings.One thingtheycan do is to de-

mystify thecurrentcommonsenseabout dependency. In thisway,we can

a

beginto clear space forenvisioning emancipatory alternatives.3

Department of Political Science

Graduate Faculty, New School for Social Research

References

Fraser,Nancy. 1992. "The Uses and Abuses of FrenchDiscourse Theories for

FeministPolitics."In RevaluingFrenchFeminism,ed. Nancy Fraserand San-

dra Bartky,177-94. Bloomington:Indiana University Press.

. 1993. "Clintonism,Welfare,and theAntisocialWage:The Emergenceof

a Neoliberal PoliticalImaginary."RethinkingMarxism6(1):9-23.

. 1994a. "Afterthe FamilyWage: Gender Equity and Social Welfare."

Political Theory22(4):591-618.

. 1994b. "Pragmatism,Feminism,and the LinguisticTurn." In Feminist

Contentions:A PhilosophicalExchange,ed. Seyla Benhabibet al. New York:

Routledge.

. 1996. "Constructing'Clients': On Stigma,Status,and SubjectPosition

in theU.S. WelfareState."In herJusticeInterruptus:

Rethinking Key Concepts

of a "Postsocialist"Age. In press.

Fraser,Nancy,and Linda Gordon. 1994. "A Genealogyof Dependency:Tracing

a Keywordof theU.S. WelfareState."Signs:Journalof Womenin Cultureand

Society19(2):309-36.

Gordon,Linda. 1994. PitiedbutNot Entitled:SingleMothersand theHistoryof

Welfare,1890-1935. New York: Free Press.

3 For moredemystification, see Fraser1993. For a considerationof some alternative

feministmodels of social welfare,see Fraser1994a.

536 SIGNS Winter 1996

This content downloaded from 143.106.1.138 on Wed, 12 Jun 2013 14:57:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- This Content Downloaded From 73.230.90.156 On Sun, 19 Mar 2023 17:51:47 UTCDocument32 paginiThis Content Downloaded From 73.230.90.156 On Sun, 19 Mar 2023 17:51:47 UTCDouglas YoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- M 1 (B) 1 An Introduction To Social Movements - atDocument40 paginiM 1 (B) 1 An Introduction To Social Movements - atpriyanshu10029Încă nu există evaluări

- Status and Organizations Theories and Cases Alexander Styhre All ChapterDocument67 paginiStatus and Organizations Theories and Cases Alexander Styhre All Chapterchris.ramos647100% (3)

- New School: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument40 paginiNew School: Info/about/policies/terms - JSP4 SumiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emirbayer and Mische 1998, What Is AgencyDocument63 paginiEmirbayer and Mische 1998, What Is AgencyHagay BarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collins - Situational StratificationDocument28 paginiCollins - Situational StratificationGonzalo AssusaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Creativity: Reconfiguring Institutional Order and ChangeDe la EverandPolitical Creativity: Reconfiguring Institutional Order and ChangeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power and Its Two Faces Revisited: A Reply To Geoffrey DebnamDocument5 paginiPower and Its Two Faces Revisited: A Reply To Geoffrey DebnamshahlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conditions of Successful Degradation CeremoniesDocument6 paginiConditions of Successful Degradation CeremoniesFernanda NathaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- AlienationDocument10 paginiAlienationAnna KokkaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Causación y Estructuras Sociales - ElderDocument16 paginiCausación y Estructuras Sociales - ElderAriel GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (1960) Becker - Notes On The Concept of CommmitmentDocument9 pagini(1960) Becker - Notes On The Concept of CommmitmentIvo Veloso VegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Structure Lecture 8Document22 paginiPolitical Structure Lecture 8Abdoukadirr SambouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Administrative CorruptionDocument10 paginiAdministrative CorruptionSh WesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970De la EverandPolitical Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970Încă nu există evaluări

- Ivan Ermakoff 2015Document63 paginiIvan Ermakoff 2015Pola Alejandra DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Melvin SeemanDocument10 paginiMelvin SeemanSri PuduÎncă nu există evaluări

- GiladAlon Barakt2018GovernanceDocument22 paginiGiladAlon Barakt2018GovernanceNehaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bendix 1947Document16 paginiBendix 1947Eugenia WahlmannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kai Erikson - Notes On The Sociology of DevianceDocument9 paginiKai Erikson - Notes On The Sociology of DevianceAndré VazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sar Press Seductions of CommunityDocument20 paginiSar Press Seductions of CommunityGuzmán de CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lect 8Document7 paginiLect 8Abdoukadirr SambouÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIGAM - Aditya - 1996 - Marxism and PowerDocument21 paginiNIGAM - Aditya - 1996 - Marxism and PowerPierressoÎncă nu există evaluări

- JO ROWLANDS EmpoderamentoDocument8 paginiJO ROWLANDS EmpoderamentoreilohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Sociological AssociationDocument11 paginiAmerican Sociological AssociationGloria Donato LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wounded Attachments Author(s) : Wendy Brown Source: Political Theory, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Aug., 1993), Pp. 390-410 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 09/05/2014 18:35Document22 paginiWounded Attachments Author(s) : Wendy Brown Source: Political Theory, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Aug., 1993), Pp. 390-410 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 09/05/2014 18:35Jonas Kunzler Moreira DornellesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mach RevisitedDocument7 paginiMach RevisitedFaizy RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Social Construction of Human Kinds - ÁstaDocument17 paginiThe Social Construction of Human Kinds - Ástaraumel romeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Sociological AssociationDocument16 paginiAmerican Sociological AssociationMauricio Fernández GioinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neutralization and SublimationDocument18 paginiNeutralization and SublimationStella ÁgostonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategy or Identity - New Theoretical Paradigms and Contemporary Social Movements by Jean L. CohenDocument55 paginiStrategy or Identity - New Theoretical Paradigms and Contemporary Social Movements by Jean L. CohenEdilvan Moraes Luna100% (1)

- Staal - On Being ReactionaryDocument15 paginiStaal - On Being ReactionaryAlfricSmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carbado, Crenshaw, Mays & Tomlinson (2013) IntersectionalityDocument11 paginiCarbado, Crenshaw, Mays & Tomlinson (2013) IntersectionalitySolSomozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ERM-7 Man & SocietyDocument8 paginiERM-7 Man & Societyxzyx9824Încă nu există evaluări

- A Theory of Role StrainDocument15 paginiA Theory of Role StrainFernando PouyÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALLPORT, Floyd Henry - Institutional Behavior - ForewardDocument42 paginiALLPORT, Floyd Henry - Institutional Behavior - ForewardJulio RochaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marshall 1981Document29 paginiMarshall 1981J LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hays StructureAgencySticky 1994Document17 paginiHays StructureAgencySticky 1994lingjialiang0813Încă nu există evaluări

- GFGHFGDocument4 paginiGFGHFGSatyam S. SundaramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blackwell Publishing American Bar FoundationDocument8 paginiBlackwell Publishing American Bar FoundationdrunkentuneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gergen and Gergen, Narratives of The Self, 1997 PDFDocument13 paginiGergen and Gergen, Narratives of The Self, 1997 PDFAlejandro Hugo GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Private Man and Society, Otto KirchheimerDocument25 paginiThe Private Man and Society, Otto KirchheimerValeria GualdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 社会资本: 理论与研究Document3 pagini社会资本: 理论与研究dengruisi51Încă nu există evaluări

- The Property-Less Sensorium Following T PDFDocument20 paginiThe Property-Less Sensorium Following T PDFDmitry BespasadniyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wednt - Collective Identity FormationDocument14 paginiWednt - Collective Identity FormationIov Claudia AnamariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talcott Parsons - On The Concept of Political PowerDocument32 paginiTalcott Parsons - On The Concept of Political Powerjogibaer5000100% (1)

- What Is EgalitarianismDocument36 paginiWhat Is EgalitarianismSeung Yoon LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot: On JustificationDocument19 paginiLuc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot: On JustificationYuti ArianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The University of Chicago PressDocument26 paginiThe University of Chicago PressPedro DavoglioÎncă nu există evaluări

- The New Social Movements Moral Crusades Political Pressure Groups or SocialDocument23 paginiThe New Social Movements Moral Crusades Political Pressure Groups or SocialCamilo Andrés FajardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Political Science Association The American Political Science ReviewDocument12 paginiAmerican Political Science Association The American Political Science ReviewJuan Manuel SuárezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jackson GruskyDocument38 paginiJackson Gruskysara_ramona7Încă nu există evaluări

- Nhops Chapter 1: I. Political Science As A DisciplineDocument11 paginiNhops Chapter 1: I. Political Science As A DisciplineNicoleMendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Have Been The Major Contributions of Critical Theories of International RelationsDocument3 paginiWhat Have Been The Major Contributions of Critical Theories of International RelationsvetakakiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lacan On The Discourse of Capitalism Critical Prospects: Philosophy, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan UniversityDocument18 paginiLacan On The Discourse of Capitalism Critical Prospects: Philosophy, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan UniversityLuiz Felipe MonteiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protecting the Elderly: How Culture Shapes Social PolicyDe la EverandProtecting the Elderly: How Culture Shapes Social PolicyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aula 4 - Moore & Tumin, 1949 - Some Social Functions of IgnoranceDocument9 paginiAula 4 - Moore & Tumin, 1949 - Some Social Functions of IgnoranceLeonardo ReitanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Klapp, O (1958) - Social Types - Process and StructureDocument6 paginiKlapp, O (1958) - Social Types - Process and StructureTesfaye TafereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Institutions and TransnationalizationDocument25 paginiInstitutions and TransnationalizationFatima AfzalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emerson1962 Power Dependence TheoryDocument12 paginiEmerson1962 Power Dependence TheoryTibet MemÎncă nu există evaluări

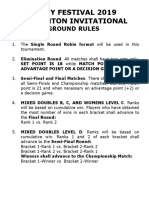

- Ground Rules 2019Document3 paginiGround Rules 2019Jeremiah Miko LepasanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bersin PredictionsDocument55 paginiBersin PredictionsRahila Ismail Narejo100% (2)

- Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsDocument3 paginiDiabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewspotatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Jest To Earnest by Roe, Edward Payson, 1838-1888Document277 paginiFrom Jest To Earnest by Roe, Edward Payson, 1838-1888Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- The Music of OhanaDocument31 paginiThe Music of OhanaSquaw100% (3)

- Nespresso Case StudyDocument7 paginiNespresso Case StudyDat NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promising Anti Convulsant Effect of A Herbal Drug in Wistar Albino RatsDocument6 paginiPromising Anti Convulsant Effect of A Herbal Drug in Wistar Albino RatsIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7cc003 Assignment DetailsDocument3 pagini7cc003 Assignment Detailsgeek 6489Încă nu există evaluări

- Los Documentos de La Dictadura Que Entregó Estados Unidos (Parte 2)Document375 paginiLos Documentos de La Dictadura Que Entregó Estados Unidos (Parte 2)Todo NoticiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Awareness CompetencyDocument30 paginiSocial Awareness CompetencyudaykumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 800 Pharsal Verb Thong DungDocument34 pagini800 Pharsal Verb Thong DungNguyễn Thu Huyền100% (2)

- Favis vs. Mun. of SabanganDocument5 paginiFavis vs. Mun. of SabanganAyra CadigalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambridge English Key Sample Paper 1 Reading and Writing v2Document9 paginiCambridge English Key Sample Paper 1 Reading and Writing v2kalinguer100% (1)

- S - BlockDocument21 paginiS - BlockRakshit Gupta100% (2)

- Conversational Maxims and Some Philosophical ProblemsDocument15 paginiConversational Maxims and Some Philosophical ProblemsPedro Alberto SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 7 1ST Quarter ExamDocument3 paginiGrade 7 1ST Quarter ExamJay Haryl PesalbonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spisak Gledanih Filmova Za 2012Document21 paginiSpisak Gledanih Filmova Za 2012Mirza AhmetovićÎncă nu există evaluări

- 25 ConstitutionDocument150 pagini25 ConstitutionSaddy MehmoodbuttÎncă nu există evaluări

- D5 PROF. ED in Mastery Learning The DefinitionDocument12 paginiD5 PROF. ED in Mastery Learning The DefinitionMarrah TenorioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applied Mechanics-Statics III PDFDocument24 paginiApplied Mechanics-Statics III PDFTasha AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spelling Master 1Document1 paginăSpelling Master 1CristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cognitive Enterprise For HCM in Retail Powered by Ibm and Oracle - 46027146USENDocument29 paginiThe Cognitive Enterprise For HCM in Retail Powered by Ibm and Oracle - 46027146USENByte MeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ma HakalaDocument3 paginiMa HakalaDiana Marcela López CubillosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approaches To Violence in IndiaDocument17 paginiApproaches To Violence in IndiaDeepa BhatiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan MP-2Document7 paginiLesson Plan MP-2VeereshGodiÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Analysis of The PoemDocument2 paginiAn Analysis of The PoemDayanand Gowda Kr100% (2)

- Dr. A. Aziz Bazoune: King Fahd University of Petroleum & MineralsDocument37 paginiDr. A. Aziz Bazoune: King Fahd University of Petroleum & MineralsJoe Jeba RajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spring94 Exam - Civ ProDocument4 paginiSpring94 Exam - Civ ProGenUp SportsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multicutural LiteracyDocument3 paginiMulticutural LiteracyMark Alfred AlemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Urinary Tract Infection in Children: CC MagbanuaDocument52 paginiUrinary Tract Infection in Children: CC MagbanuaVanessa YunqueÎncă nu există evaluări