Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

History and Prehistory: The Title Page To La Historia D'italia

Încărcat de

Raymond BaroneDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

History and Prehistory: The Title Page To La Historia D'italia

Încărcat de

Raymond BaroneDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

"fill the gaps" within textual sources.

Indeed, "historical archaeology" is a specific branch of archaeology, often contrasting its

conclusions against those of contemporary textual sources. For example, Mark Leone, the excavator and interpreter of historical

Annapolis, Maryland, USA; has sought to understand the contradiction between textual documents and the material record,

demonstrating the possession of slaves and the inequalities of wealth apparent via the study of the total historical environment,

despite the ideology of "liberty" inherent in written documents at this time.

There are varieties of ways in which history can be organized, including chronologically, culturally, territorially, and thematically.

These divisions are not mutually exclusive, and significant overlaps are often present, as in "The International Women's Movement in

an Age of Transition, 1830–1975." It is possible for historians to concern themselves with both the very specific and the very general,

although the modern trend has been toward specialization. The area called Big History resists this specialization, and searches for

universal patterns or trends. History has often been studied with some practical or theoretical aim, but also may be studied out of

simple intellectual curiosity.[22]

History and prehistory

The history of the world is the memory of the pastexperience of Homo sapiens sapiens around the world, as that experience has been

preserved, largely in written records. By "prehistory", historians mean the recovery of knowledge of the past in an area where no

written records exist, or where the writing of a culture is not understood. By studying painting, drawings, carvings, and other

artifacts, some information can be recovered even in the absence of a written record. Since the 20th century, the study of prehistory is

considered essential to avoid history's implicit exclusion of certain civilizations, such as those of Sub-Saharan Africa and pre-

Columbian America. Historians in the West have been criticized for focusing disproportionately on the Western world.[23] In 1961,

British historian E. H. Carr wrote:

The line of demarcation between prehistoric and historical times is crossed when people cease to live only in the

present, and become consciously interested both in their past and in their future. History begins with the handing

down of tradition; and tradition means the carrying of the habits and lessons of the past into the future. Records of the

[24]

past begin to be kept for the benefit of future generations.

This definition includes within the scope of history the strong interests of peoples, such as Indigenous Australians and New Zealand

Māori in the past, and the oral records maintained and transmitted to succeeding generations, even before their contact with European

civilization.

Historiography

Historiography has a number of related meanings. Firstly, it can refer to how history

has been produced: the story of the development of methodology and practices (for

example, the move from short-term biographical narrative towards long-term

thematic analysis). Secondly, it can refer to what has been produced: a specific body

of historical writing (for example, "medieval historiography during the 1960s"

means "Works of medieval history written during the 1960s"). Thirdly, it may refer

to why history is produced: the Philosophy of history. As a meta-level analysis of

descriptions of the past, this third conception can relate to the first two in that the

analysis usually focuses on the narratives, interpretations, world view, use of

evidence, or method of presentation of other historians. Professional historians also

debate the question of whether history can be taught as a single coherent narrative or

a series of competing narratives.[25][26]

The title page to La Historia d'Italia

Philosophy of history

History's philosophical questions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Encyclopedia of South AfricaDocument11 paginiEncyclopedia of South AfricaLittleWhiteBakkie100% (1)

- Is storytelling and drama powerful tools in teachingDocument17 paginiIs storytelling and drama powerful tools in teachingummiweewee100% (1)

- Building An Organization Capable of Good Strategy Execution: People, Capabilities, and StructureDocument31 paginiBuilding An Organization Capable of Good Strategy Execution: People, Capabilities, and Structuremrt8888100% (1)

- Concept of HistoryDocument2 paginiConcept of HistoryEhsan KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- English 7 Activity Sheet: Quarter 3 - MELC 1Document16 paginiEnglish 7 Activity Sheet: Quarter 3 - MELC 1Ann Margarit Tenales100% (1)

- 3962 PDFDocument3 pagini3962 PDFKeshav BhalotiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zzzzizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoiz PDFDocument441 paginiZzzzizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoizoiz PDFramón adrián ponce testino100% (1)

- Tratado de Cardiología: BraunwaldDocument26 paginiTratado de Cardiología: BraunwaldkiyukxeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charles TILLY - Historical SociologyDocument5 paginiCharles TILLY - Historical SociologyIrina IvanencoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Empirical Futures: Anthropologists and Historians Engage the Work of Sidney W. MintzDe la EverandEmpirical Futures: Anthropologists and Historians Engage the Work of Sidney W. MintzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bevir-Historicism, Human Sciences Victorian BritainDocument20 paginiBevir-Historicism, Human Sciences Victorian BritainrebenaqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- History - The Academic Study of Past EventsDocument3 paginiHistory - The Academic Study of Past EventsCamila DanieleÎncă nu există evaluări

- History and Prehistory: The Title Page To La Historia D'italiaDocument2 paginiHistory and Prehistory: The Title Page To La Historia D'italiaRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Untitled DocumentDocument1 paginăUntitled DocumentlinaungkhantbrainworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- History (from Greek ἱστορία - historia, meaning "inquiry, knowledgeDocument3 paginiHistory (from Greek ἱστορία - historia, meaning "inquiry, knowledgeCristina SoaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Description: Benedetto CroceDocument2 paginiDescription: Benedetto CroceRobinson AntonioÎncă nu există evaluări

- History (From: Greek Prehistory Umbrella Term Historians Narrative Nature of HistoryDocument5 paginiHistory (From: Greek Prehistory Umbrella Term Historians Narrative Nature of HistoryAmit TiwariÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoriansDocument2 paginiHistoriansNothingÎncă nu există evaluări

- History: The Study of the PastDocument7 paginiHistory: The Study of the PastEmpire100Încă nu există evaluări

- History - WikipediaDocument150 paginiHistory - WikipediaJackson LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- History - WikipediaDocument155 paginiHistory - Wikipediashrimati.usha.sharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- C (From: Greek Information Past Historians Narrative Objectively Cause and EffectDocument6 paginiC (From: Greek Information Past Historians Narrative Objectively Cause and EffectN. SWAROOP KUMARÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoryDocument37 paginiHistoryThulaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- History - WikipediaDocument37 paginiHistory - WikipediaRohit MarandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etymology: History (FromDocument9 paginiEtymology: History (FromJeremy Espino-SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- History Through the AgesDocument21 paginiHistory Through the AgesVarrun JunejaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Study of Our Past: A Brief History of the Academic Discipline of HistoryDocument19 paginiThe Study of Our Past: A Brief History of the Academic Discipline of HistoryJCV LucenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoryDocument6 paginiHistoryOjas JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- History from Greek for inquiry and investigationDocument16 paginiHistory from Greek for inquiry and investigationGrimReaperÎncă nu există evaluări

- ELK Enunciating The Core Principles of Twenty First Century Historiography Sujay Rao MandavilliDocument101 paginiELK Enunciating The Core Principles of Twenty First Century Historiography Sujay Rao MandavilliSujay Rao MandavilliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historiography: The Title Page To"la Historia D'italia"Document1 paginăHistoriography: The Title Page To"la Historia D'italia"delldell13Încă nu există evaluări

- Communication TheoryDocument89 paginiCommunication Theoryshivam tyagiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sachsenmaier, Dominic. The Evolution of World HistoriesDocument28 paginiSachsenmaier, Dominic. The Evolution of World HistoriesHenrique Espada LimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoryDocument4 paginiHistoryJeremy T. GilbaligaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History: 1 EtymologyDocument17 paginiHistory: 1 EtymologytarunÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoryDocument3 paginiHistoryZannatul FerdausÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tacitus & SpanglarDocument12 paginiTacitus & SpanglarWaqar MahmoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Screenshot 2023-01-24 at 8.57.05 AM PDFDocument10 paginiScreenshot 2023-01-24 at 8.57.05 AM PDFKimberly Pascua ArizÎncă nu există evaluări

- History: The Study of the PastDocument9 paginiHistory: The Study of the Pastschauhan12Încă nu există evaluări

- AIOU-Historiography Study Guide Feb 2018Document124 paginiAIOU-Historiography Study Guide Feb 2018mroman12049Încă nu există evaluări

- Aurell - What Is A Classic in HistoryDocument38 paginiAurell - What Is A Classic in HistorysfterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Description: Ancrene Wisse Confessio AmantisDocument3 paginiDescription: Ancrene Wisse Confessio AmantisStudmed MedstudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ch. 1 The Study-WPS OfficeDocument4 paginiCh. 1 The Study-WPS OfficeAyenshi HitoriÎncă nu există evaluări

- History M1515Document6 paginiHistory M1515ama kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoryDocument9 paginiHistoryschauhan12Încă nu există evaluări

- History and HistoriographyDocument4 paginiHistory and HistoriographyVaishnav KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoriographyDocument10 paginiHistoriographymidou89Încă nu există evaluări

- Historyical TrendsDocument139 paginiHistoryical TrendsPraveen Kumar100% (1)

- History: Chronicle Spring and Autumn AnnalsDocument9 paginiHistory: Chronicle Spring and Autumn Annalsschauhan12Încă nu există evaluări

- History: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument19 paginiHistory: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchWilsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ge2 HistoryDocument64 paginiGe2 HistoryMicaela EncinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- His TwikiDocument19 paginiHis TwikiSorinÎncă nu există evaluări

- A History of Historiography: Hayden White On History WritingDocument63 paginiA History of Historiography: Hayden White On History WritingUrvashi BarthwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 - Definition, Issues and MethodologyDocument13 paginiModule 1 - Definition, Issues and Methodologyrichard reyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 (Writing The Paper Proposal)Document23 paginiModule 1 (Writing The Paper Proposal)JON RED SUVAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature and History InterwovenDocument31 paginiLiterature and History InterwovenArchana KumariÎncă nu există evaluări

- History as a Study of the PastDocument6 paginiHistory as a Study of the PastA Parel DrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction of History Chapter 1Document8 paginiIntroduction of History Chapter 1Lowela Mae BenlotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wesleyan University, Wiley History and TheoryDocument29 paginiWesleyan University, Wiley History and TheoryfauzanrasipÎncă nu există evaluări

- BROWN, Vincent - Mapping A Slave Revolt (2015)Document8 paginiBROWN, Vincent - Mapping A Slave Revolt (2015)Preta PátriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History Socsci Group 4Document6 paginiHistory Socsci Group 4richelleannmanalotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Article Is About The Academic DisciplineDocument1 paginăThis Article Is About The Academic DisciplineanjanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Science Fullversion PDFDocument70 paginiHistory of Science Fullversion PDFSharif M Mizanur RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition, Issues, Sources and Methodology in History - 0Document29 paginiDefinition, Issues, Sources and Methodology in History - 0xyndelrose arelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction Assessing Narrativism PDFDocument10 paginiIntroduction Assessing Narrativism PDFPhillipe ArthurÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 3Document1 paginăHistory 3Raymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistDocument2 paginiHistRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of South AmericaDocument1 paginăHistory of South AmericaRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistDocument2 paginiHistRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historians: World HistoryDocument1 paginăHistorians: World HistoryRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 3Document1 paginăHistory 3Raymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistDocument2 paginiHistRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistDocument2 paginiHistRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 17 PDFDocument1 paginăHistory 17 PDFRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Periods: Prehistoric PeriodisationDocument3 paginiPeriods: Prehistoric PeriodisationRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Further Reading: The American Historical Association's Guide To Historical LiteratureDocument1 paginăFurther Reading: The American Historical Association's Guide To Historical LiteratureRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural History: SubfieldsDocument1 paginăCultural History: SubfieldsRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- HistoryDocument17 paginiHistoryRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historical Methods: War. Thucydides, Unlike Herodotus, Regarded History As Being The Product of TheDocument1 paginăHistorical Methods: War. Thucydides, Unlike Herodotus, Regarded History As Being The Product of TheRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Periods: Prehistoric PeriodisationDocument1 paginăPeriods: Prehistoric PeriodisationRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 17 PDFDocument1 paginăHistory 17 PDFRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of South AmericaDocument1 paginăHistory of South AmericaRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 15Document1 paginăHistory 15Raymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historians: World HistoryDocument1 paginăHistorians: World HistoryRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of South AmericaDocument1 paginăHistory of South AmericaRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- References: Other ThemesDocument1 paginăReferences: Other ThemesRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Judgement of History: Scholarship Vs TeachingDocument1 paginăThe Judgement of History: Scholarship Vs TeachingRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 1Document1 paginăHistory 1Raymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Periods: Prehistoric PeriodisationDocument1 paginăPeriods: Prehistoric PeriodisationRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marxian Theory of HistoryDocument1 paginăMarxian Theory of HistoryRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historians: World HistoryDocument1 paginăHistorians: World HistoryRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 17 PDFDocument1 paginăHistory 17 PDFRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- History 15Document1 paginăHistory 15Raymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marxian Theory of HistoryDocument1 paginăMarxian Theory of HistoryRaymond BaroneÎncă nu există evaluări

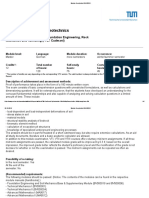

- Geotechnik Blockprüfung - Module Description BGU50010Document5 paginiGeotechnik Blockprüfung - Module Description BGU50010Devis CamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st Century Skills - How Do We Prepare Students For The New Global EconomyDocument22 pagini21st Century Skills - How Do We Prepare Students For The New Global EconomyOng Eng TekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Only: Competency-Based Standards For Rank-and-File Employees Assessment ToolDocument2 paginiSample Only: Competency-Based Standards For Rank-and-File Employees Assessment ToolJerry Barad SarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homeo Summer CampDocument12 paginiHomeo Summer CampsillymindsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virtual Learning Packet in Pattern Drafting and Designing For Garments, Fashion and Design StudentsDocument8 paginiVirtual Learning Packet in Pattern Drafting and Designing For Garments, Fashion and Design StudentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equivalents Record Form: I. Educational Attainment & Civil Service EligibilityDocument2 paginiEquivalents Record Form: I. Educational Attainment & Civil Service EligibilityGrace StraceÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Code of Ethics For Professional TeachersDocument7 paginiThe Code of Ethics For Professional TeachersRoden RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smoothie Lesson Plan 2Document3 paginiSmoothie Lesson Plan 2api-324980546Încă nu există evaluări

- ESC Certification Assessment InstrumentDocument46 paginiESC Certification Assessment InstrumentJayco-Joni CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhatt Counseling BrochureDocument2 paginiBhatt Counseling Brochureapi-366056267Încă nu există evaluări

- Report of The Fourth Project Meeting SylvieDocument3 paginiReport of The Fourth Project Meeting SylvieXAVIERÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 2Document19 paginiModule 1 2AnthonyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Form 2 Write Short ParagraphDocument2 paginiLesson Plan Form 2 Write Short ParagraphAqilah NasuhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Ability Sample QuestionsDocument2 paginiCognitive Ability Sample Questionskc exalt100% (1)

- Old BibliDocument5 paginiOld BibliIvannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synthesis Explorer: A Chemical Reaction Tutorial System For Organic Synthesis Design and Mechanism PredictionDocument5 paginiSynthesis Explorer: A Chemical Reaction Tutorial System For Organic Synthesis Design and Mechanism PredictionWinnie NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Individual Learning Monitoring PlanDocument2 paginiIndividual Learning Monitoring PlanLiam Sean HanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook For Public Safety CPSC PUB-325 241534 7Document47 paginiHandbook For Public Safety CPSC PUB-325 241534 7asimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness of Multigrade Instruction in Lined With The K To 12 Curriculum StandardsDocument7 paginiEffectiveness of Multigrade Instruction in Lined With The K To 12 Curriculum StandardsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review EFL Syllabus Design.Document3 paginiLiterature Review EFL Syllabus Design.Ayhan Yavuz100% (2)

- Resume FormatDocument3 paginiResume FormatSantoshKumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Top Government Jobs in IndiaDocument5 pagini4 Top Government Jobs in IndiahiringcorporationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using Sound Boxes Systematically To Develop Phonemic AwarenessDocument5 paginiUsing Sound Boxes Systematically To Develop Phonemic Awarenessalialim83Încă nu există evaluări

- Fee Structure: S. Details of Fee Total Fee No. Payable (RS.)Document13 paginiFee Structure: S. Details of Fee Total Fee No. Payable (RS.)SidSinghÎncă nu există evaluări