Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Anderson (2014) Seafaring in Remote Oceania, Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime Technology and Migration

Încărcat de

Karen RochaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Anderson (2014) Seafaring in Remote Oceania, Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime Technology and Migration

Încărcat de

Karen RochaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Oxford Handbooks Online

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and

Beyond in Maritime Technology and Migration

Atholl Anderson

The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Oceania

Edited by Ethan E. Cochrane and Terry L. Hunt

Print Publication Date: May 2018 Subject: Archaeology, Archaeology of Oceania

Online Publication Date: Oct 2014 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199925070.013.003

Abstract and Keywords

Long-distance seafaring or voyaging is often understood in a traditionalist perspective

that assumes particular sail and watercraft technology for which there is no physical

evidence, a capability for search-and-return voyages of discovery, a degeneration of

voyaging technology over time, and an isomorphism between the ethnographic and pre-

European records. This chapter reviews the ethnohistoric, ethnographic, and linguistic

evidence pertaining to Oceanic boats and sailing rigs and concludes that prior to about

A.D. 1500 Oceanic sailing rigs were mastless without triangular sails and had no

weatherly capability. This conclusion has ramifications for the explanation of the episodic

nature of Oceanic colonization and post-colonization interaction.

Keywords: seafaring, voyaging, colonization, interaction, Oceanic boats

Introduction

LONG-DISTANCE seafaring, often characterized ambiguously as “voyaging,” was the core

activity of Pacific colonization, most emphatically in Remote Oceania where minimum

distances between islands were often over 500 km, and up to 4,000 km. Yet, no other

major topic in Oceanic prehistory has proven so intractable, for almost no remains of

offshore boats have been described and seafaring left neither a pre-European record of

the structure and rigging of boats, except enigmatically in rock art, nor more than a faint

ethnographic trace of the basic techniques of long-distance sailing, navigation, and

seakeeping. That Oceanic seafaring can be discussed at all depends largely, and

tenuously, upon its construction by proxy. Transcribed oral traditions of voyaging,

European historical observations, and historical linguistics have been combined to shape

Page 1 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

proxies for prehistoric seafaring technology and performance, while patterns of island

colonization and interaction, inferred from the distribution and dating of archaeological

remains, plus Oceanic geography and sailing simulation, have provided proxy narratives

of migration history. Explanation of these, turning with uncomfortable circularity back to

foundation issues of seafaring technology and performance, has ranged in recent

discussion from ebullient traditionalism (e.g., Howe 2006) to conservative historicism

(e.g., Anderson 2008).

That dichotomy of perspectives—here simplifying a broader range of approaches—

originated in acerbic criticism of the traditionalist model of voyaging by Andrew Sharp

(1957) and reactions to that in Golson (1963). Polynesian navigational ability formed a

(p. 474) lightning rod for much of that debate, as it had historically (Durrans 1979), but it

is not discussed here. In my experience, and by the assurance of more accomplished

navigators (e.g., Lewis 1994), a knowledge of rising and zenith stars, coupled with dead

reckoning, could provide a workable system of navigation on passages east‒west, while

the immense band of islands stretching across the central Pacific provided a safety net of

sorts for passages toward the equator (see map in the essay by Cochrane and Hunt). That

such methods could have been sufficiently effective in Oceanic prehistory is accepted

widely today.

An equally fundamental issue, and now the main topic of debate, is the nature of Oceanic

long-distance sailing in relation to maritime migration. Following a critique of

traditionalism, which is still the prevailing model, I discuss the changing character of

sailing technology and performance between the mid-Holocene and the era of European

exploration. Seafaring technology at the moving front of prehistoric migration across

Remote Oceania is most pertinent, but it is important to note that technology and

performance continued to change when initial migration phases were over and that they

did so by continuing introduction of technical novelty as well as by regional innovation. Of

comparable importance is variation in sailing conditions, a crucial and often missing

element in discussion of maritime migration.

I use “seafaring” as the general term for oceanic sailing and reserve “voyaging,” with its

implication of planned passages, to mean seafaring that has been asserted as purposeful

in traditional narratives or traditionalist perspectives, or for which some other

contention, such as evidence of two-way trade, supports an assumption that it was so.

Traditionalist Voyaging

The traditionalist approach to voyaging in Remote Oceania developed from a late

nineteenth-century conviction that Polynesian traditions were a reliable, primary source

for the history of Pacific colonization (Shortland 1854; Fornander 1878–1885). In some

respects this is demonstrably probable. For example, multiple and substantially

independent tribal genealogies and narratives amongst Maori agree that initial migration

Page 2 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

to New Zealand involved numerous canoes and occurred eighteen to twenty-two

generations before about 1840, a proposition entirely consistent with modern

archaeological, genetic, and paleoenvironmental evidence. However, none of the Remote

Oceanic traditions recorded in early historical sources referred in detail to the technology

and practice of seafaring. Such material came, dubiously, in more elaborate late

nineteenth- and early twentieth-century versions of voyaging traditions (Smith 1904; Best

1923; Buck 1938) that underpin the continuing traditionalist model (Finney 1979; Irwin

1992; Lewis 1994; Howe 2006; Pearce and Pearce 2010).

European and indigenous scholars read Polynesian colonizing traditions to imply the

existence of large, fast, weatherly (windward-sailing) double canoes, precise astral

navigation, and frequent, intentional, return voyaging. As few of these features had been

(p. 475) observed historically, it was concluded that Polynesian seafaring had been more

sophisticated during the colonization era than at the time of early European observation.

That “principle of degeneration” (Dening 1963: 102) underwrote a confident belief in an

age of unrestrained voyaging, followed by degeneration in long-distance seafaring

capability. This traditionalist voyaging model encompassed various propositions, each

open to debate.

The first is that voyagers could sail where and when they pleased on fast return passages,

deciding later whether to establish colonies. Assertion that two-way voyages could make

average speeds (Velocity made good, Vmg) of 4‒6 knots (Smith 1904; Finney 2006a: 132)

is contradicted by historical evidence, including information from the Tahitian Tupaia to

Cook, in 1769, showing that the 2,600 nautical mile round trip, Tahiti‒Tonga, was sailed

at 2.6 knots Vmg (Anderson 2008: 269), in itself a comparatively strong performance

(Whiteright 2011). Evidence of frequent return voyaging is scarce. For example, the

Eastern Lapita (Fiji/West Polynesia) ceramic system was isolated and soon decayed,

presumably through lack of inter-archipelago interaction, while New Britain obsidian,

common in Santa Cruz, hardly reached New Caledonia, Fiji, or West Polynesia (Clark and

Anderson 2009). Post-Lapita movement is indicated by Polynesian influence in Vanuatu,

and by West Polynesian pottery and adzes in central East Polynesia (Weisler 1997), but

there is no impression of regular exchange. Similarly, some central East Polynesian

material reached Hawai‘i, Easter Island, or New Zealand but no convincing instances of

return have been documented (e.g., Anderson 2008 contra Collerson and Weisler 2007).

The delayed colonization argument (Graves and Addison 1995) assumes long retention of

precise sailing instructions, but these do not appear in early oral traditions, and,

archaeologically, the first reliable signs of human habitation on Remote Oceanic islands

are almost invariably followed by evidence of continuous settlement.

The hypothesis that Polynesians sailed to and from the Americas, founded in a

traditionalist perspective, needs mention here. In recent form, it envisages the

introduction of chickens to pre-Columbian Chile and the return from Ecuador of

Polynesian canoes bearing sweet potato (Jones et al. 2011). The chicken-bone DNA has no

specifically Polynesian signature, however, and the few radiocarbon dates suggest a mid-

fifteenth-century age, too close to Spanish chicken introduction around A.D. 1500 to be

Page 3 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

confident about the source (Thomson et al. 2014). Conversely, Amerindian sailing to

Polynesia has long been suggested by multiple trait similarities in Easter Island

monumental architecture, “tupa” structures and a distinctive bird man motif, while large,

weatherly, sailing rafts seen by Spanish explorers in Ecuador could have reached

Polynesia, conveniently downwind, bringing also the sweet potato and gourd (Anderson,

Martinsson-Wallin, and Stothert 2007; Montenegro, Avis, and Weaver 2008). Both

hypotheses could be valid, and each requires more research. Similar claims that

Polynesian voyaging reached California from Hawai‘i (Jones et al. 2011) are constructed

around the existence of the Chumash Indian planked canoe, or tomol. The linguistic

argument that “tomol” has a Polynesian origin is thoroughly unconvincing. Furthermore,

as the tomol existed centuries before Hawai‘i was colonized, the hypothesis is feeble

(Arnold 2007).

(p. 476)A second traditionalist tenet, that Remote Oceanic exploration and colonization

involved systematic voyaging, had no basis for testing until Irwin (1992) proposed a long-

term voyaging strategy in which exploration was deliberately directional. It began toward

the prevailing wind direction, enabling a safe return, and later, as information

accumulated, set off across and then down the main wind directions. In seeking useful

cases, Irwin (2010: 138) took the absence of Lapita sites either side of Torres Strait as

supporting his strategic model, but there is now evidence of Lapita settlement in

southern Papua New Guinea (David et al. 2011). In East Polynesia the colonization

chronology (Wilmshurst et al. 2011) suggests that discovery of the marginal islands

occurred more or less simultaneously, yet Easter Island is upwind into the trades, Hawai‘i

is mainly downwind in the trades, and New Zealand lies in a very different and varied

temperate system. Furthermore, as soon as New Zealand was discovered, migrants set

off in all directions and found the outlying islands at 500‒800 km distant (see Anderson

essay on Southern Polynesia), again simultaneously within the limits of radiocarbon

dating. These data refute the proposition that there was a systematic strategy of

exploratory sailing with respect to prevailing winds. In addition, the general thrust of

Remote Oceanic colonization directly into the southeast trade winds, which gave rise to

that idea, is primarily a function of geography. The main bands of islands are aligned

northwest‒southeast, and migration originated in the northwest, so most new islands

were discovered progressively to the southeast, irrespective of seafaring strategies.

A third traditionalist proposition is that long-distance sailing throughout Polynesia came

to an end in the late fifteenth century by information passing among the islands to say

that no more were open to colonization, thus reducing the need for voyaging canoes. Yet

large double canoes under sail were common in Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Societies, Hawai‘i,

and New Zealand when Europeans arrived and some fragments of historical evidence

show that long-distance voyaging continued in tropical Polynesia, including voyages

between Tahiti and Tonga. Similarly, as knowledge of iron preceded the arrival of

Europeans in isolated islands such as Rapa, lengthy voyaging must have continued or

resumed. The issue, rather, may be the extent to which post-colonization seafaring can be

detected. Polynesian traditions of that period generally refer to the arrival of newcomers

within the context of hostilities, as in islands subjected to the late prehistoric Tongan

Page 4 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

hegemony (see Burley and Addison essay). The peaceful arrival of migrants might have

happened largely unnoticed in the traditions after A.D. 1500 because their impact would

have been lessened progressively by expanding resident populations and a consequent

weakening in the extent of intra-population communication. There has been little specific

analysis of this matter in Oceanic research of any kind, and the danger remains that

relative clarity in the signal of initial colonization is distorting our impression of migration

continuity.

Fourth, is the traditionalist assertion of technological degeneration. Some adaptation to

unusual local conditions had certainly occurred by the eighteenth century. Yet, even the

raft-canoe of Chatham Islands Moriori was hardly degenerate. It was an ingenious

reduction of the double canoe to a framework that, with built-in buoyancy, produced

(p. 477) an unsinkable pontoon boat suited to the sea conditions. Other maritime

technologies in East Polynesia have been held to represent retention of technology

transferred during the colonization era. Haddon and Hornell (1975: 1:208) argued that

the Maori sailing rig “either preserved an extremely archaic and primitive design,

improved elsewhere into the Oceanic lateen, or else it was a degenerate form of the

lateen. The probability is altogether in favour of its archaic character.” Most importantly,

after about A.D. 1500, Remote Oceanic maritime technology generally was on a trajectory

of innovative development, not degeneration (discussed later).

A fifth proposition of traditionalist thinking was that most of the sailing technology that

existed in early historical Remote Oceania had always been there. This undiscriminating,

ethnographic perspective encourages construction of experimental Polynesian canoes

that combine favorable elements of technology from across the region and beyond,

irrespective of when or where they originated; for example, the combination of Hawaiian

spritsails, Tongan lateen halyards and masts, and European deadeyes and headsails

creates powerful sailing rigs that never existed historically. Traditionalism, with its

ahistorical bent, failed to comprehend the technical transformation that occurred in the

mid-second millennium A.D. That failure also confounds simple evolutionary approaches

to seafaring technology. Rogers and Ehrlich (2008; Rogers, Feldman, and Ehrlich 2009)

modeled a cultural lineage of Polynesian canoe traits as a case of evolutionary change.

Using data from Haddon and Hornell (1975), they argued that as functional traits

changed more slowly than symbolic traits, the former were under negative or

conservative selective pressure. While hypothetically plausible, the validity of

demonstration depends upon the traits having evolved, or not, within the same selective

environment, and in Remote Oceania that is simply not the case. Many Polynesian canoe

traits are clearly external introductions from late prehistoric lateen rigs, or from

European technology. In other words, the pattern of variation in the ethnographic record

was formed significantly by late technological invasion rather than by selective pressure

in situ.

Criticism of traditionalism (notably by Sharp 1957) gave rise to new ways of testing

alternative hypotheses, by computer simulation and experimental voyaging. Initial

research in simulated voyaging showed that the probability of finding the marginal

Page 5 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Polynesian islands by drifting under sail was extremely low, and therefore that those

passages, at least, were sailed intentionally (Levison, Ward, and Webb 1973). Later

simulation (Irwin 1992, 2010), tested discovery probabilities across a range of voyaging

scenarios and showed, logically, that these increased with hypothetical increases in

sailing capability. Simulation, however, cannot determine which scenario is most realistic;

whether discovery occurred by more passages with lower technology or fewer passages

with higher technology. That still comes back to evaluation of indirect evidence about how

long-distance seafaring was actually accomplished. Experimental sailing has often been

used in the latter role, but it is severely limited by compromises in construction,

navigation, and performance that stem from an inherent contradiction between scientific

seafaring experiments and a concomitant cultural requirement of manifest success in

voyaging (Anderson 2000, 2008; Finney 2006b).

Prevailing views about ancient Polynesian seafaring remain as strongly

(p. 478)

traditionalist as ever (notably in Howe 2006) and, in the latest manifestation, hyper-literal

interpretation of traditions creates a bizarrely improbable Pacific prehistory that Pearce

and Pearce (2010) attempt to validate mathematically. Alternative perspectives have been

resisted, not least by indigenous determination to hold on to the popular estimation in

which traditionalism is held. Rethinking Remote Oceanic seafaring is thus more than the

task of occasional or specific criticism, and its achievement is not a realistic objective

here. Nevertheless, it is worth starting along that path by going back to the basics of

Pacific boats and sailing rigs.

Maritime Technology

Page 6 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Oceanic Boats

Propositions about hypothetical sequences of canoe development have varied

considerably. Haddon and Hornell (1975: 3:76) settled upon a sequence of double

outriggers in the Indo-Pacific, then single outriggers in Oceania and, lastly, double

canoes. Doran (1981), arguing from a premise of increasing seaworthiness, reversed that

order, and Horridge (2008) proposed double outriggers, then double canoes and single

outriggers, suggesting that the latter two were used in Austronesian migration.

Contemporary evidence that might assist evaluation of these schemes is scarce.

Island Southeast Asian rock art includes pictures of boats which, in the main, probably

belong to an “Austronesian painting tradition” (Ballard et al. 2003; Bulbeck 2008).

Against the expectation that these would depict outrigger canoes none do so, although

that might have been difficult in the side-on perspective adopted (Lape, O’Connor, and

Burningham 2007). None of the rock-art boats has been radiocarbon dated directly and

some are probably very recent. Others, though, are stylistically similar to boats shown on

Dong Son drums, dating about 3,000‒2,000 B.P. and they confirm, at least, the existence

of quite large canoes in the Austronesian source area at about the time of early

migrations into Remote Oceania. Of hulls, little remains. Logboats, dating from modern

back to the early Mesolithic are common throughout Southeast Asia, but their shallow

hulls are not of a seagoing form, except in inshore waters. Nor were dugouts, unless

fitted with stabilizers or an outrigger. Suggested evidence of early Holocene outriggers in

China is unconvincing, as Lape, O’Connor, and Burningham (2007) explain. The earliest,

indirect, archaeological evidence of outriggers, is from Sri Lanka and dates about 300

B.C. (McGrail 2001: 266), while the earliest depiction of outriggers in Southeast Asia is in

A.D. eighth- to ninth-century engravings at Borobudur, Java (McGrail 2001: 307).

From historical linguistics (see essay by Pawley), Pawley and Pawley (1998; Pawley 2002)

doubt Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) *katiR = “outrigger canoe” (accepted later by

Pawley 2007 on some WMP reflexes), but accept PMP *(c,s)a(R) (p. 479) man = “outrigger

float” on meanings that, at best, refer to the float indirectly. The terms *waga = canoe,

and *patoto = outrigger connecting sticks, have been moved down from Malayo-

Polynesian (MP) by Pawley (2007) to join other terms associated with outrigger

technology; *katae = canoe side without outrigger, *patar = canoe platform, and *kiajo =

outrigger boom, which have Proto-Oceanic (POc) origins (Pawley and Pawley 1998),

equated with Lapita from the Bismarcks to eastern Melanesia. Perhaps the spread of

terms suggests lengthy development more than sudden innovation, with meanings in the

MP stage referring not to outriggers in the modern sense, but to their precursors such as

bamboo floats attached directly to hulls. If the Donohue and Denham (2012) argument

that POc may have origins that stretch as far eastward as Fiji is valid, then the true

outrigger could postdate the beginning of Lapita expansion into Remote Oceania.

Page 7 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

The double canoe is more clearly an eastern Oceanic innovation. Pawley and Pawley

(1998) suggest Proto-Eastern-Oceanic (PEOc) *paqurua, for double canoe and cognates

are most common across Polynesia; those found further west are likely indications of the

extent of downwind sailing back into the west Pacific, notably to the “Polynesian outliers”

after the main Polynesian colonizations. As “rua” (two) was applied to canoes exclusively

in Eastern Oceanic, the double canoe probably arose in Fiji/West Polynesia, perhaps long

after Lapita colonization. Several planks, possibly from a double canoe platform, a

steering oar, and other canoe pieces were found in a wet site on Huahine Island, Society

group, and recovered partly by dredge (Sinoto and McCoy 1975). Whether they date to

the lowest level, about 1,000‒900 B.P., or were sunk in the pond sometime later is

uncertain.

Canoes may not have been the only vehicles of Remote Oceanic colonization, or the first.

A PMP term *dakit has been reconstructed for “raft” (Pawley and Pawley 1998), and

bamboo rafts were used historically for offshore sailing in Indo-China and Taiwan and

probably much earlier. The large sailing ship depicted at Borobudur appears to have a

raft hull (McGrail 2001: 310). The advantages of a raft for colonization are its inherent

seaworthiness and load-carrying capacity. An 8m long bamboo raft loaded to 50% of

displacement could carry 3,150 kg (Anderson 2010), the weight of seventeen adults and

sufficient stores for thirty days, affording a reasonable chance of colonizing success. By

comparison an 11.5 m long double canoe could carry less than half that weight and it

would need to be 18 m long to match the raft. Outrigger canoes of comparable lengths

had lower carrying capacities again. Perhaps large double canoes were conceived as

surrogates for colonizing rafts in the eastern Pacific, where large bamboo was scarce.

Computer simulation of a drifting vessel under sail (Avis, Montenegro, and Weaver 2008),

the situation of a raft, showed a mean crossing time of thirty-one days from Santa Cruz to

Vanuatu in summer months when monsoon or El Niño westerlies were available. The

general results of that study suggested that drifting under sail was capable of colonizing

Santa Cruz, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia (POc *raki(t) = “raft” would take in those

archipelagos but it did not extend into Proto Central Pacific (PCP) of Fiji/West Polynesia

or later), but that active sailing of canoes was probably needed to reach Fiji/West

Polynesia. In regard to Western Micronesia, Hung et al. (2011) argue for a long passage

by weatherly sailing canoes from the northern Philippines, but Winter et al. (2011)

(p. 480) show that this is very improbable and note that computer simulation (Callaghan

and Fitzpatrick 2008) of drifting under sail suggests the most likely origin of colonization

in Palau would have been from the area between the southern Philippines and

Halmahera.

There are few secure conclusions to be derived about the boats in the early Austronesian

migrations to Remote Oceania. The earliest movements may have been on sailing rafts,

perhaps as far east as Vanuatu/New Caledonia. Migrations further east were more

certainly in sailing canoes. How early there were outriggers in the historical sense is

uncertain. The modern consensus is that Lapita canoes were single outriggers (Irwin

Page 8 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

2010), which is plausible even if hardly demonstrable. Double canoes developed later,

probably in West Polynesia.

Oceanic Sailing Rigs

Successful colonization of Remote Oceania relied upon the advent of sail, as indicated by

a sixfold increase, beginning about 3,500 years ago, in the range of Indo-Pacific seaborne

activity (Anderson 2004). The same trend suggests that sailing had not existed in the

region any earlier. Had there been sailing in Near Oceania during the Pleistocene, or

indeed any effective form of sail up to the mid-Holocene, then crossing some 300 km to

Remote Oceania should have occurred much earlier than it did. As ideographic,

iconographic, and documentary evidence dates earliest sailing in India and China to the

early and late second millennium B.C., respectively (Anderson 2010; McGrail 2010: 103),

it probably began then in island Southeast Asia, reaching Remote Oceania soon

afterward.

The earliest type of sailing rig is often assumed to have involved a V-shaped sail attached

to converging spars that were joined together, at or near the base, to form a semi-rigid

triangular foil. Horridge (1986: 92) proposed that this two-boomed rig, formed “an

archetype of the whole eastward expansion into the Pacific.” It is very difficult to

document that contention for there are no archaeological remains of sailing rigs and

historical evidence of sails from island Southeast Asia begins late, in the early first

millennium A.D. It portrays narrow squaresails set horizontally or aslant on a fixed mast

(McGrail 2001: 308). Squaresails were the early form in the Indian Ocean and China up

until the second millennium A.D. (McGrail 2001: 278, 357) and, in Near Oceania, square

or quadrilateral sails were dominant historically in the islands north of New Guinea

(Ambrose 1997). Enigmatic structures on canoes in East Indonesian rock art probably

represent sails (O’Connor 2003; Lape, O’Connor, and Burningham 2007), but masts are

seldom shown and the sails are mainly quadrilateral. There is, then, little to support the

view that Oceanic sailing began with a triangular sail, and strut or mast.

In historical linguistics, PMP *layaR = sail, is generic and no PMP terms refer to spars or

rigging, except for *tuku = “prop, post, mast,” an ambiguous term. They begin much

later; e.g., POc *jila = “boom or yard of (triangular) sail,” PEOc *kaiu-tuqu(r) = “vertical

supporting timber, prop supporting rig,” and PEOc *pana = “mast, boom stepped in foot

of mast” (Pawley and Pawley 1998: 195‒196). The glosses are likely to be misleading,

however, because they read the maritime technology of the distant past in modern

(p. 481) terminology. As proposed later, masts and booms may not have been in existence

in Oceania before the arrival of lateen technology, in which case the POc terms probably

referred to spars used in other configurations. No Oceanic terms for standing rigging are

constructed and running stays are not attested linguistically before PCP, *tuku = “running

stay supporting mast [or spar]” (Pawley and Pawley 1998: 197), having changed its

earlier specific meaning (Pawley 2007: 27‒28) while retaining a general sense of

Page 9 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

“support.” If the scarcity of terms for stays is significant, a predominance of mastless rigs

is implied.

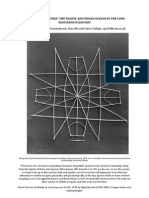

By the time of European

arrival, masted rigs with

triangular sails were

common in Remote

Oceania and included

various forms of the

Oceanic spritsail. That has

a largely East Polynesian

distribution (Haddon and

Hornell 1975: 3:83;

McGrail 2001: 334), which,

Click to view larger in part, may be related to

Figure 21.1 The early or “tongiaki” form of Oceanic the influence of the

lateen sailing rig in Tonga, A.D. 1616. Oceanic lateen (reversing

Source: Published originally in Spieghel der the relationship suggested

AustralischeNavigatie, 1622. Image courtesy of the by Campbell 1995). In its

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New

Zealand. developed form, the

Oceanic lateen existed by

the early sixteenth century in western Micronesia so if it came from the Mediterranean

lateen, taken into the Indian Ocean by the Portuguese, then it did so extremely rapidly.

More likely, it had origins in lateen sail types used by Arabian seafarers from at least the

fourteenth century (McGrail 2001: 75). In any event, double canoes under the Oceanic

lateen were reported as far east as Tonga by the early seventeenth century, but under the

relatively primitive tongiaki rig with its fixed-stays mast they lay closer to the wind on one

tack than the other and went about through the wind (Figure 21.1). By the late eighteenth

century, the more efficient kalia rig with canting mast and the shunting method of going

about had come into vogue. Kalia-rigged double canoes typically had a smaller windward

hull and in this respect, as in the rig, they were effectively scaled-up versions (p. 482) of

the Micronesian proa. Their singular merit was a weatherliness that probably had not

existed until that time in Remote Oceania.

The second millennium A.D. transformation in Remote Oceanic sailing rigs had a wide-

ranging impact. Within the area where lateen technology was concentrated, Micronesia

and Fiji/West Polynesia, seafaring involving exchange and, to some degree, tribute and

political suzerainty, developed into extensive maritime chiefdoms (e.g., in Yap with

respect to central Micronesia). Yapese traditions about Palauan stone money suggest that

this system began, or was intensified, in the fifteenth century, and Tongan expansionism,

although beginning several centuries earlier, also seems to have gathered pace from the

fifteenth century (Clark, Burley, and Murray 2008; Clark 2010). I have argued that the

new technology was adapted piecemeal on the margins of its range (Anderson 2000). The

idea of a fixed mast which facilitated some windward capacity, and a balance board that

enabled higher tension in the shrouds and thus larger sails and greater speed, spread to

Page 10 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

the Society Islands, and to some extent beyond, creating an advanced sailing ability

which further extended the range of contact. It is reflected in the relatively extensive

geographical knowledge of the eighteenth-century Tahitians, as opposed to much more

limited horizons elsewhere. In Hawai‘i, one spar was stayed as a mast, possibly as a

result of contact with Tahiti, but in a way that made windward sailing impractical, even if

technically possible, and Marquesan sails were similar. In the Gambiers, a spritsail with

strut was used on rafts.

In contrast, islands that were largely or entirely beyond the influence of lateen

technology had mastless rigs of various forms. Some of these used two-boomed triangular

sails as in Vanuatu (Haddon and Hornell 1975: 2:25‒31). Rectangular sails were possibly

used in the southern Cook Islands (Buck 1927), and sails of unspecified form, but no fixed

masts, were noted in the Australs and Rapa. The fullest evidence is from New Zealand,

where a tall, quadrilateral sail was observed on the first double canoe seen in 1769. An

ambiguous description of it has been taken to imply a fixed mast and trailing spar (Irwin

2006), but a contemporary sketch showed that the rig consisted of two movable spars

with running forestays and sheets attached. This was a downwind rig and when the canoe

eventually broke off contact with the Endeavour and stood back to its base, upwind, the

sail was doused and the vessel was paddled. Joseph Banks (Morrell 1958: 139) got the

description right once he became familiar with the rig, writing that “we very seldom saw

them make use of sails and indeed never unless when they were to go right before the

Wind. They were made of Mat and instead of a mast were hoisted upon two sticks which

were fastned one to each side” (Figure 21.2).

It can be proposed that the New Zealand rig exemplifies a class of mastless sails used

across Remote Oceania before the arrival of the Oceanic lateen. Some may have been

triangular, but large sails of this kind are more easily rigged if they are rectangular or

quadrilateral and that, in turn, provided a facility to shape the sail to take the wind on

angles that approached a beam reach. There has been only one experiment in using such

a sailing rig on a small double canoe and it showed that while sailing angles up to a beam

reach (i.e., sailing across the direction of the wind) were possible in a light breeze, boat

speed fell off quickly and windward sailing was impractical (Anderson and Boon 2011).

(p. 483) It can be surmised that when the fixed-stay mast arrived with the lateen rig, the

older triangular and quadrilateral sails were adapted to it by closing their spars at the

base. Stepping one spar as a mast at the transverse midpoint of the hulls compelled the

other to be attached to it, and doing so produced the Oceanic spritsail and a small

weatherly capacity.

Page 11 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

On the inadequate

evidence that exists

presently, then, early

Austronesian sailing rigs

may have had neither mast

nor triangular sail. They

might have consisted

mainly of quadrilateral

sails, held up by lateral

Click to view larger spars, which were each

Figure 21.2 Sketch by Herman Spöring of double fixed loosely at the base, to

canoe with quadrilateral sail on movable spars, New

allow independent fore-

Zealand, A.D. 1769.

and-aft movement using

Source: Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull

Library, Wellington, New Zealand. sheets and running stays.

If so, then seafaring in

Remote Oceania before about A.D. 1500 had little or no weatherly capacity and long

passages to windward were largely precluded. From the sixteenth century, sailing on the

margins of lateen dispersal had acquired some windward ability and that spread north to

Hawai‘i and west to Melanesia.

Seafaring Performance and Migration

Pause and Pulse

The traditionalist model entailed a logical imperative requiring seafarers in possession of

a sophisticated technology to make colonization of Remote Oceania a more or less

(p. 484) continuous process, which meant early migration to East Polynesia. Kirch (1986)

proposed settlement of central East Polynesia 3,000‒2,200 B.P. and Irwin (1992: 216) a

colonization chronology that began in the Cook Islands and Societies at 2,700‒2,600 B.P.,

reached Hawai‘i and Easter Island 1,700 B.P., and New Zealand 1,200 B.P. This

continuity proposition attracted support from early paleoenvironmental research arguing

human intervention as early as 2,500 B.P. in the Cook Islands and 2,000 B.P. in New

Zealand but methodological problems (Anderson 1995) brought renewed analyses putting

initial anthropogenic change in East Polynesia within the last 1,000 years (e.g.,

Wilmshurst et al. 2008). Re-dating of East Polynesian archaeological sites (see Rieth’s

essay) with existing radiocarbon ages of up to 2,200 B.P. showed similarly that human

colonization of East Polynesia did not begin until around 1,000 B.P. and that marginal

islands were not colonized until about 700 B.P. (Dye 1992; Rolett and Conte 1995;

Anderson and Sinoto 2002; Wilmshurst et al. 2011). There can be little doubt, then, that

advancing colonization in Remote Oceania was a discontinuous process.

Page 12 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

At a theoretical level, that is an expected pattern because migration begins/ends

universally in an episodic fashion through lowered/raised perception of opportunity at

source, dissatisfaction/satisfaction of experience at destination, and decreasing/

increasing climatic, demographic, socioeconomic, or technological resistance.

Nevertheless, the punctuated pattern of Remote Oceanic migration invites conjecture at a

regional level. It is an artificial construction to the extent that it emphasizes migration

into hitherto uncolonized islands at the probable expense of migration continuing after

colonization, but the sequence of expansion into new territory is interesting for the way in

which it exemplifies a serial and binary model of migration mobility involving stable,

largely time-transgressive phases and unstable, largely space-transgressive pulses

(Anderson 2001). West Micronesian and Lapita pulses occurred more or less together at

approximately 3,300‒2,900 B.P. and were followed by a stable phase that ended 2,200‒

2,000 B.P. in a colonization pulse to central Micronesia and other islands marginal to

Lapita migration, such as the northern Cooks, Niue, and Rotuma. Following a stable

phase, the sequence was repeated with a colonization pulse to central East Polynesia,

around 1,100‒900 B.P., a brief stable phase, and then another pulse to marginal East

Polynesia. As East Polynesian colonization probably came directly from West Polynesia, a

“long pause” of around 2,000 years (Wilmshurst et al. 2011) is implied, and this is

supported by historical linguistics (Pawley 1999).

Whether the semi-regular occurrence of migration pulses implies the operation of some

inherent dynamic of island colonization is worth consideration. It has been argued that

migration ought to occur at two points in a logistic curve of population growth, first at the

point of rapid early growth where consumer impact upon resources is initially apparent

and then later as population density approaches some objective measure of carrying

capacity (Keegan’s 1995 A-type and K-type migrations, respectively). Perhaps the main

pulses were A-type dispersals seeking to maintain nutritional levels and rapid population

growth as soon as some decline became apparent in the high-quality resources of

formerly pristine island ecosystems, with the secondary pulses being K-type migrations

reflecting significant population pressure. It might be noted that Lapita (p. 485) migration

seems to have been running out of migrants at the eastern end of its range, whereas

migration from the Societies to New Zealand was described in oral traditions as exile

arising from disputes about land, food, and status (Anderson 2006).

The longest pause was on the edge of the West‒East Polynesian gap where the band of

large, numerous, and ecologically varied islands stretching back into Near Oceania comes

to an end. West of it, Lapita migration had more than twenty times the land-capture rate

of East Polynesian dispersal, measured by the proportion of land area to dispersal area

(cf. Irwin 2010), until late and fortuitous discovery of the huge New Zealand landmass

(Clark and Anderson 2009). If the long pause represents colonization success of one kind

in the Lapita region, that is, finding enough land for a millennium of settlement before

substantial migration pressures set in again, then migration to and within East Polynesian

may represent it in another way. The predominance of small islands east of the gap

encouraged more frequent migration seafaring at low population densities, as is

suggested by an accelerating rate of dispersal (Irwin 1992; Anderson 2001). Within

Page 13 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

colonizing pulses of several hundred years in each case, Lapita migration extended 4,680

km across 21° of latitude, and East Polynesian migration 8,700 km across 70° of latitude

(Clark and Anderson 2009).

It is also hardly coincidence that the Lapita boundary and the subsequent long pause

were at the proximal edge of a largely barren seaway nearly twice as wide as the

broadest in the Lapita region. The long passages across it were hardly changed by the

late first-millennium A.D. retreat of the hydro-isostatic highstand in sea level (Dickinson

2003). That brought numerous atolls either side of the seaway but virtually none within it.

Thus, the effect of the double canoe, when it became available in West Polynesia, was to

lower part of the technological resistance to new migration by creating a carrying

capacity sufficient to maintain a viable colonizing group plus its essential gear and

supplies for a month or more at sea. There is, though, no reason to think that it had any

better sailing performance than existed earlier, and eastward migrations continued to

face strong climatic resistance, especially in wind directions.

Sailing Conditions

Wind conditions have long been recognized as a critical factor in eastward migration, as

implied in the truism that sailing capability is inversely related to favorability of sailing

conditions. If migrations occurred before following winds, then no advanced sailing

capability was required; but if migrations reached destinations that lay upwind, then a

weatherly capability existed. Given that sailing conditions over the long term were much

as they are today, the standard assumption in Polynesian voyaging research, then

colonization of tropical Remote Oceania had generally to push upwind against the trades

going east (and upwind against mid-latitude westerlies going southwest to New Zealand),

hence the emphasis upon weatherly technology in traditionalist perspectives. Nobody was

going anywhere much without it. What is more, the resistance increased eastward as the

trades became stronger and steadier. This has been illustrated in simulated voyaging

(p. 486) by Di Piazza, Di Piazza, and Pearthree (2007) who found that whereas passages

from Vanuatu to Fiji could be made within wide arcs of success for most of the year, those

east of Samoa were much more difficult. From Samoa to the northern Cooks the target

angles were small and passages feasible for only seven weeks a year. Courses from

Samoa produced a small percentage of successful landfalls in the Marquesas and

Societies (cf. Levison, Ward, and Webb 1973: 60, using a 90° sailing angle). From Samoa

to the southern Cooks, feasibility was reduced to one week per year. These simulations

used modern canoe performance, where progress is possible to within 75° of the wind

direction, but a more conservative assumption, that sailing could not extend windward of

90°, especially in open sea conditions (Whiteright 2011), would probably make at least

the last of those routes impossible.

But what if sailing conditions were different during the colonization period, and routes

that are now upwind were then downwind? Explanations of altered voyaging frequency or

success have emphasized the significance of El Niño to eastward voyaging; El Niño

Page 14 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

conditions weaken the dominant trade wind flow and induce a higher frequency of

westerly winds. However, while El Niño events occur frequently they are seldom

sufficiently persistent to push a sailing vessel eastward across the larger sea gaps in

Oceania. When that does happen, the greatest impact is in latitudes 0‒14° South. This

range includes sailing from Samoa to the northern Societies and Marquesas but not to

the southern Cooks. El Niño conditions also increase humidity in the east Pacific while

causing drought to the west. Successively poor growing seasons in western islands may

have favored migration as a solution, while unusually lush conditions on newly discovered

eastern islands might have reinforced attraction in that direction. Analysis of proxy

records of climate for the last 4,500 years shows that periods of migration coincided

approximately with major frequency peaks in El Niño conditions when there was an

enhanced probability of long-lasting episodes of westerly winds in the tropics. El Niño

frequency was relatively high at various points 3,400‒2,400 B.P., which might have

assisted Lapita and subsequent migration. Another set of high frequency peaks occurred

1,500‒1,200 B.P., the period in which movement may have begun into East Polynesia, and

a third very high peak at 800‒700 B.P. when the main expansion of colonization occurred

in East Polynesia (Anderson et al. 2006).

The South Polynesian region (New Zealand and its outlying islands, see Anderson’s essay

on South Polynesia) was also colonized about 700 B.P., but on courses opposite to those

of eastward migration in tropical Polynesia. The key variable was probably the latitudinal

span and persistence of subtropical easterly winds. In this regard, new research on the

predominant prehistoric locations of the main pressure systems, relevant to sailing from

the Cooks and Australs toward New Zealand, shows that about 1,250‒850 B.P. there were

persistent blocking highs in the Tasman Sea, which sent westerlies across New Zealand

and directed easterly winds well to the north, making it difficult to sail south beyond the

subtropics. From 850 to 650 B.P., the high pressure systems were generally to the east of

New Zealand and they, together with low pressure cells in the Tasman Sea, turned the

southeasterly trades progressively into northeasterly and then northerly winds

approaching New Zealand, conditions unusually conducive to sailing from East (p. 487) to

South Polynesia. By 600 B.P., the high pressure systems were weaker and low pressure

predominated over New Zealand, the combination restoring a westerly flow that

effectively closed the route to downwind sailing for the remainder of the prehistoric era

(Goodwin, Browning, and Anderson, 2014). Colonization seafaring when winds along the

route from central East Polynesia to South Polynesia were generally abaft the beam

would have been relatively easy and quite fast. That does not mean that canoes could not

sail to windward, but it gets around the traditionalist assumption that such technology

was necessary. It is a solution to the East Polynesian voyaging problem that requires no

need to postulate any additional technology, or conjunction of dispersed technical

elements, than that which was recorded historically.

Page 15 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Conclusions

In considering the study of ancient seafaring globally, the archaeological recovery of

boats and related maritime technology provides the vital evidence for basic concepts of

maritime technology and performance, as in northern Europe and the Mediterranean.

The virtual absence of such direct evidence concerning long-distance sailing in Remote

Oceania is a severe obstacle to any coherent understanding of the topic and it is in that

deficiency of deep historical record that traditionalism continues to flourish (e.g., Howe

2006). Traditionalism reduces temporality to a generalized ethnographic present that is

blind to historiographical differences in traditional narratives, it obscures temporal

differences in maritime technology and practice within the early European period and it

fails to comprehend those inferred within the pre-European era. Further, traditionalism

takes no more than a passing interest in the broader maritime history of the Indo-Pacific,

or the implications for sailing conditions in Remote Oceania of the varied climatic history

of the ocean. Although popular with scholars and public alike, traditionalism has long

outlived its usefulness to the study of Remote Oceanic seafaring.

The way forward requires a much stricter and scientifically focused historical approach to

documentary and other records, the use of historically documented and case-appropriate

parameters in simulation and experimental sailing, and contextualization of Remote

Oceanic seafaring research within global oceanic history, prehistory, and associated

environmental histories. In the final analysis, though, our being compelled to analysis by

proxy should spur explicit programs of research aimed at finding technological remains,

especially of migration canoes, upon which any robust comprehension of Remote Oceanic

seafaring really depends.

For the present, some general points about Remote Oceanic seafaring can be made. First

and foremost, it depended upon the mid-late Holocene advent of sail. Second, which sails

and with what performance characteristics remains quite uncertain. Traditionalist

confidence in the early existence of triangular sails with stayed masts and weatherly

ability is poorly founded. A conjectural case for mastless rigs with no windward ability

and possibly using quadrilateral sails suits the sparse evidence better. Third, (p. 488) sail

technology changed substantially in Remote Oceanic prehistory. If, as suggested here, the

Oceanic spritsail arose by adapting some technical features of the Oceanic lateen, which

arrived in the mid-second millennium A.D., then the colonization of Remote Oceania was

accomplished without a windward sailing ability and it may have depended substantially

upon periodic changes in sailing conditions.

The strongest feature of Remote Oceanic migration is that it was strongly episodic rather

than continuous, at least as measured by punctuated progress in the advancing front of

initial human colonization. Discontinuity can be inferred hypothetically as arising from

demographic responses in variable conditions of relative resource scarcity. Long-term

migration pulsing was modulated by west‒east variation in island geography, and

changes in sailing conditions, boats, and sails. Those created a seafaring pattern that

Page 16 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

varied eastward, and toward higher latitudes, from one in which some degree of agency

and interaction can be inferred, especially late in prehistory, to another in which they

cannot and where isolation was prevalent.

References

Ambrose, W. R. 1997. “Contradictions in Lapita pottery: A composite clone.” Antiquity 71:

525–538.

Anderson, A. J. 1995. “Current approaches in East Polynesian colonization research.”

Journal of the Polynesian Society 104: 110–132.

Anderson, A. J. 2000. “Slow boats from China: Issues in the prehistory of Indo-Pacific

seafaring.” Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia 16: 13–50.

Anderson, A. J. 2001. “Mobility models of Lapita migration.” Pp. 15–24 in The Archaeology

of Lapita Dispersal in Oceania, Terra Australis 17, ed. G. R. Clark, A. J. Anderson, and T.

Vunidilo. Canberra: ANU.

Anderson, A. J. 2004. “Islands of ambivalence.” Pp. 251–274 in Voyages of Discovery: The

Archaeology of Islands, ed. S. Fitzpatrick. London: Praeger.

Anderson, A. J. 2006. “Islands of exile: Ideological motivation in maritime migration.”

Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 1: 33–48.

Anderson, A. J. 2008. “Forum: Traditionalism, interaction and long-distance seafaring in

Polynesia.” Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 3: 240–270.

Anderson, A. J. 2010. “The origins and development of seafaring: Towards a global

approach.” Pp. 3–16 in The Global Origins and Development of Seafaring, ed. A.

Anderson, J. Barrett, and K. Boyle. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Anderson, A. J., and H. Boon. 2011. “East Polynesian sailing rigs: The Anuta Iti

experiment.” Journal of Pacific Archaeology 2: 109–113.

Anderson, A. J., and Y. H. Sinoto. 2002. “New radiocarbon ages of colonization sites in

East Polynesia.” Asian Perspectives 41: 242–257.

Anderson, A. J., H. Martinsson-Wallin, and K. Stothert. 2007. “Ecuadorian sailing rafts and

oceanic landfalls.” Pp. 117–133 in Vastly Ingenious: Papers on Material Culture in Honour

of Janet M. Davidson, ed. A. J. Anderson, K. Green, and B. F. Leach. Dunedin: University of

Otago Press.

Anderson, A. J., J. Chappell, M. Gagan, and R. Grove. 2006. “Prehistoric maritime

migration in the Pacific islands: An hypothesis of ENSO forcing.” The Holocene 16: 1–6.

Page 17 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Arnold, J. E. 2007. “Credit where credit is due: The history of the Chumash

(p. 489)

oceangoing plank canoe.” American Antiquity 72: 196–209.

Avis, C., A. Montenegro, and A. Weaver. 2008. “Simulating island discovery during the

Lapita expansion.” Pp. 121–142 in Canoes of the Grand Ocean, ed. A. Di Piazza and E.

Pearthree. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Ballard, C., R. Bradley, L. Nordenborg Myhre, and M. Wilson. 2003. “The ship as symbol

in the prehistory of Scandinavia and south-east Asia.” World Archaeology 35: 385–403.

Best, E. 1923. Polynesian Voyages. Dominion Museum Monograph, 5. Wellington.

Buck, P. H. 1927. The Material Culture of the Cook Islands, Aitutaki. New Plymouth:

Thomas Avery.

Buck, P. H. 1938. Vikings of the Sunrise. New York: Lippincott.

Bulbeck, D. 2008. “An integrated perspective on the Austronesian diaspora: The switch

from cereal agriculture to maritime foraging in the colonisation of island southeast Asia.”

Australian Archaeology 67: 31–51.

Callaghan, R. T., and S. M. Fitzpatrick. 2008. “Examining prehistoric migration patterns

in the Palauan Archipelago: A computer simulated analysis of drift voyaging.” Asian

Perspectives 47: 28–44.

Campbell, I. C. 1995. “The lateen sail in world history.” Journal of World History 6: 1–23.

Clark, G. R. 2010. “The sea in the land: Maritime connections in the chiefly landscape of

Tonga.” Pp. 229–237 in The Global Origins and Development of Seafaring, ed. A.

Anderson, J. Barrett, and K. Boyle. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Clark, G. R., and A. J. Anderson. 2009. “Colonisation and culture change in the early

prehistory of Fiji.” Pp. 407–437 in The Early Prehistory of Fiji, Terra Australis 31, ed. G.

R. Clark and A. J. Anderson. Canberra: ANU.

Clark, G. R., D. V. Burley, and T. Murray. 2008. “Monumentality in the development of the

Tongan maritime chiefdom.” Antiquity 82: 994–1004.

Collerson, K. D., and M. I. Weisler. 2007. “Stone adze compositions and the extent of

ancient Polynesian voyaging and trade.” Science 317: 1907–1911.

David, B., I. J. NcNiven, T. Richards, S. P. Connaughton, M. Leavesly, B. Barker, and C.

Rowe. 2011. “Lapita sites in the central province of mainland Papua New Guinea.” World

Archaeology 43: 580–597.

Dening, G. M. 1963. “The geographical knowledge of the Polynesians and the nature of

inter-island contact.” Pp. 102–136 in Polynesian Navigation, ed. J. Golson. Wellington: The

Polynesian Society.

Page 18 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Dickinson, W. 2003. “Impact of mid-Holocene hydro-isostatic highstand in regional sea

level on habitability of islands.” Journal of Coastal Research 19: 489–502.

Di Piazza, A., P. Di Piazza, and E. Pearthree. 2007. “Sailing virtual canoes across Oceania:

Revisiting island accessibility.” Journal of Archaeological Science 34: 1219–1225.

Donohue, M., and T. Denham. 2012. “Lapita and Proto-Oceanic, thinking outside the pot.”

Journal of Pacific History 47: 443–457.

Doran, E., Jr. 1981. Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. College Station, Texas: A & M

University Press.

Durrans, B. 1979. “Ancient Pacific voyaging: Cook’s views and the development of

interpretation.” Pp. 137–166 in Captain Cook and the South Pacific, ed. T. C. Mitchell.

Canberra: Australian University Press.

Dye, T. 1992.“The South Point radiocarbon dates thirty years later.” New Zealand Journal

of Archaeology 14: 89–97.

(p. 490) Finney, B. R. 1979. Hokule’a: The Way to Tahiti. New York: Dodd, Mead.

Finney, B. R. 2006a. “Ocean sailing canoes.” Pp. 101–153 in Vaka Moana, ed. K. R. Howe.

Auckland: Bateman.

Finney, B. R. 2006b. “Renaissance.” Pp. 289–333 in Vaka Moana, ed. K. R. Howe.

Auckland: Bateman.

Fornander, A. 1878–1885. An Account of the Polynesian Race. 3 vols. London: Kegan Paul.

Golson, J. (ed.) 1963.Polynesian Navigation: A Symposium on Andrew Sharp’s Theory of

Accidental Voyages. Wellington: The Polynesian Society.

Goodwin, I. D., J. Browning, and A. J. Anderson. 2014. “A Medieval Climatic Anomaly

Window for East Polynesian Voyaging to New Zealand and Easter Island.” Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences 111(41): 14716–14721.

Graves, M. W., and D. J. Addison. 1995. “The Polynesian settlement of the Hawaiian

archipelago: Integrating models and methods in archaeological interpretation.” World

Archaeology 26: 380–399.

Haddon, A. C., and J. Hornell. 1975. Canoes of Oceania. Honolulu: B. P. Bishop Museum.

Horridge, A. 1986. “The evolution of Pacific canoe rigs.” Journal of Pacific History 21: 83–

99.

Horridge, A. 2008. “Origins and relationships of Pacific canoes and rigs.” Pp. 85–105 in

Canoes of the Grand Ocean, ed. A. Di Piazza and E. Pearthree. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Howe, K. R. (ed.) 2006. Vaka Moana: Voyages of the Ancestors. Auckland: David Bateman.

Page 19 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Hung, H., M. T. Carson, P. Bellwood, F. Z. Campos, P. J. Piper, E. Dizon, M. J. Bolunia, M.

Oxenham, and Z. Chi. 2011. “The first settlement of Remote Oceania: The Philippines to

the Marianas.” Antiquity 85: 909–926.

Irwin, G. J. 1992. The Prehistoric Exploration and Colonisation of the Pacific. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Irwin, G. J. 2006. “Voyaging and settlement.” Pp. 55–91 in Vaka Moana, ed. K. R. Howe.

Auckland: Bateman.

Irwin, G. J. 2010. “Pacific voyaging and settlement: Issues of biogeography and

archaeology, canoe performance and computer simulation.” Pp. 131–141 in The Global

Origins and Development of Seafaring, ed. A. Anderson, J. Barrett, and K. Boyle.

Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Jones, T. L., A. A. Storey, E. A. Matisoo-Smith, and J. M. Ramírez-Aliaga (eds.) 2011.

Polynesians in America: Pre-Columbian Contacts with the New World. Lanham, MA:

Altamira Press.

Keegan, W. F. 1995. “Modelling dispersal in the prehistoric West Indies.” World

Archaeology 26: 400–420.

Kirch, P. V. 1986. “Rethinking East Polynesian prehistory.” Journal of the Polynesian

Society 95: 9–40.

Lape, P. V., S. O’Connor, and H. Burningham. 2007. “Rock art: A potential source of

information about past maritime technology in the south-east Asia-Pacific

region.”International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 36: 238–253.

Levison, M., R. G. Ward, and J. W. Webb. 1973. The Settlement of Polynesia: A Computer

Simulation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Lewis, D. 1994. We, the Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific.

Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

McGrail, S. 2001. Boats of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McGrail, S. 2010. “The global origins of seagoing water transport.” Pp. 95–107 in The

Global Origins and Development of Seafaring, ed. A. Anderson, J. Barrett, and K. Boyle.

Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Montenegro, A., C. Avis, and A. Weaver. 2008. “Modeling the prehistoric arrival

(p. 491)

of the sweet potato in Polynesia.” Journal of Archaeological Science 35: 355–367.

Morrell, W. P. (ed.) 1958. Sir Joseph Banks in New Zealand. Wellington: Reed.

O’Connor, S. 2003. “Nine new painted rock-art sites from East Timor in the context of the

western Pacific region.” Asian Perspectives 42: 96–128.

Page 20 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Pawley, A. 1999. “Chasing rainbows: Implications of the rapid dispersal of Austronesian

languages for subgrouping and reconstruction.” Pp. 95–138 in Selected Papers from the

Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, ed. E. Zeitoun and P. Li.

Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Pawley, A. 2002. “The Austronesian dispersal: Languages, technologies and people.” Pp.

251–273 in Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis, ed. P. Bellwood and

C. Renfrew. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Pawley, A. 2007. “The origins of early Lapita culture: The testimony of historical

linguistics.” Pp. 17–49 in Oceanic Explorations: Lapita and Western Pacific Settlement,

Terra Australis 26, ed. S. Bedford, C. Sand, and S. Connaughton. Canberra: ANU E-Press.

Pawley, A., and M. Pawley. 1998. “Canoes and seafaring.” Pp. 173–209 in The Lexicon of

Proto Oceanic, Volume 1:Material Culture, Pacific Linguistics C–152, ed. M. Ross, A.

Pawley, and M. Osmond. Canberra: The Australia National University.

Pearce, C. E. M., and F. M. Pearce. 2010. Oceanic Migration: Paths, Sequence, Timing and

Range of Prehistoric Migration in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Heidelberg: Springer.

Rogers, D. S., and P. R. Ehrlich. 2008. “Natural selection and cultural rates of change.”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105: 3416–3420.

Rogers, D. S., M. W. Feldman, and P. R. Ehrlich. 2009. “Inferring population histories

using cultural data.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 276: 3835–3843.

Rolett, B. V., and E. Conte. 1995. “Renewed investigation of the Haatuatua Dune (Nuku

Hiva, Marquesas Islands): A key site in Polynesian prehistory.” Journal of the Polynesian

Society 104: 195–228.

Sharp, A. 1957. Ancient Voyagers in the Pacific. London: Penguin.

Shortland, E. 1854. The Traditions and Superstitions of the New Zealanders. London:

Longmans.

Sinoto, Y. H., and P. C. McCoy. 1975. “Report on the preliminary excavation of an early

habitation site on Huahine, Society Islands.” Journal de la Société des Océanistes 47:

143–186.

Smith, S. P. 1904. Hawaiki, the Original Home of the Maori, with a Sketch of Polynesian

History. Wellington: Whitcombe and Tombs.

Thomson, V. A., O. Lebrasseur, J. A. Austin, T. L. Hunt, D. A. Burney, T. Denham, N. J.

Rawlence, J. R. Wood, J. Gongora, L. G. Flink, A. Linderholm, K. Dobney, G. Larson, and A.

Cooper. 2014. “Using ancient DNA to the study the origins and dispersal of ancestral

Polynesian chickens across the Pacific.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science

111: 4826–4831.

Page 21 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

Seafaring in Remote Oceania: Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime

Technology and Migration

Weisler, M. I. (ed.) 1997. Prehistoric Long-Distance Interaction in Oceania: An

Interdisciplinary Approach. NZAA Monograph 21. Dunedin: New Zealand Archaeological

Association.

Whiteright, J. 2011. “The potential performance of ancient Mediterranean sailing rigs.”

International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 40: 2–17.

Wilmshurst, J. M., A. J. Anderson, T. G. F. Higham, and T. H. Worthy. 2008. “Dating the late

prehistoric dispersal of Polynesians to New Zealand using the commensal Pacific rat.”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104: 7676–7680.

Wilmshurst, J., T. Hunt, C. Lipo, and A. Anderson. 2011. “High-precision

(p. 492)

radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia.”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105: 7676–7680.

Winter, O., G. Clark, A. Anderson, and A. Lindahl. 2012. “Austronesian sailing to the

northern Marianas, a comment on Hung et al. (2011).” Antiquity 86: 898–914.

Atholl Anderson

Atholl Anderson Emeritus Professor, School of Culture, History and Language, The

Australian National University, Australia.

Page 22 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 21 September 2018

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Seafaring Capabilities in The Pre-Columbian Caribbean Scott M. FitzpatrickDocument38 paginiSeafaring Capabilities in The Pre-Columbian Caribbean Scott M. FitzpatrickDionisio MesyeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aztec, Salmon, and the Puebloan Heartland of the Middle San JuanDe la EverandAztec, Salmon, and the Puebloan Heartland of the Middle San JuanPaul F. ReedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prehistory of PolynesiaDocument37 paginiPrehistory of PolynesiaKaren RochaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cuban Table A Celebration of Food Flavors and History Ana SofiaDocument536 paginiThe Cuban Table A Celebration of Food Flavors and History Ana SofiaUbaldo Sanchez100% (1)

- The Eland'S People: Edited by Peter Mitchell and Benjamin SmithDocument22 paginiThe Eland'S People: Edited by Peter Mitchell and Benjamin SmithLuaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Photography PathfinderDocument8 paginiHistory of Photography PathfinderJason W. DeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mihaia (9781927131305) - BWB Sales SheetDocument2 paginiMihaia (9781927131305) - BWB Sales SheetBridget Williams BooksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polynesian LanguageDocument8 paginiPolynesian LanguageSándor Tóth100% (1)