Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Trance States-A Theoretical and Cross Cultural Model

Încărcat de

Bobby Black100%(2)100% au considerat acest document util (2 voturi)

112 vizualizări31 paginiThis paper presents a psychophysiological model of trance states. It relates these changes to the basic structure and physiology of the brain. Trance induction techniques lead to a state of parasympathetic dominance.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThis paper presents a psychophysiological model of trance states. It relates these changes to the basic structure and physiology of the brain. Trance induction techniques lead to a state of parasympathetic dominance.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

100%(2)100% au considerat acest document util (2 voturi)

112 vizualizări31 paginiTrance States-A Theoretical and Cross Cultural Model

Încărcat de

Bobby BlackThis paper presents a psychophysiological model of trance states. It relates these changes to the basic structure and physiology of the brain. Trance induction techniques lead to a state of parasympathetic dominance.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 31

Trance States: A Theoretical Model and Cross-Cultural Analysis

Michael Winkelman

Ethos, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Summer, 1986), 174-203

Stable URL:

btp//links jstor.org/sici2sici=0091-2131%28198622%29 14% 3A2%3C174%3ATSATMA%3E2.0,CO%3B2-B

Exhos is currently published by American Anthropological Association,

‘Your use of the ISTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

hhup:/www.jstororg/about/terms.hml. JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you

have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and

you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

hup:/www jstor.org/journals/anthro. hl

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the sereen or

printed page of such transmission,

STOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of

scholarly journals, For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact jstor-info@ umich edu,

upslwww jstor.org/

Wed Jan 14 16:25:52 2004

Trance States:

A Theoretical Model and Cross-Cultural Analysis

MICHAEL WINKELMAN

INTRODUCTION

The role of trance states or altered states of consciousness (ASCs)

in human societies has been an issue of concern among anthropol-

ogists (for example, see Bourguignon 1968, 1976a, 1976b; Lex 1976,

1979; Peters and Price-Williams 1980; Prince 1982a, 1982b; Jilek

1982; Heinze 1983; Noll 1983; Locke and Kelly 1985). Although a

few articles have addressed the psychophysiological basis of trance

states or the relationship of trance induction procedures to the

psychophysiology of consciousness (for example, Lex 1979; Prince

1982a, 1982b), most investigators have implicitly or explicitly as-

sumed that trance states of different practitioners and in different

societies are similar or identical without explication of the grounds

for such assumptions.

‘This paper presents a psychophysiological model of trance states,

and relates these changes to the basic structure and physiology of

the brain. It is argued that a wide variety of trance induction tech-

niques lead to a state of parasympathetic dominance in which the

frontal cortex is dominated by slow wave patterns originating in the

limbie system and related projections into the frontal parts of the

brain, Psychophysiological research on the effects of a variety of

trance induction procedures is reviewed to illustrate that these pro-

cedures have the consequence of inducing this set of changes in psy-

MICHAEL WINKELMAN is Research Anthropologist, School of Social Sciences, Univer-

74

TRANCESTATES 175

chophysiology. Clinical and neurophysiological research on the na-

ture of human temporal lobe function and dysfunction is reviewed

to illustrate that the physiological patterns of conditions frequently

labeled as pathological are similar to the psychophysiology of trance

states, Analyses of cross-cultural data on trance state induction pro-

cedures and characteristics are presented. The model of a single

type of trance state associated with magico-religious practitioners is

tested and shown to be significantly better than a model represent-

ig trance states as discrete types, supporting the theoretical posi

tion that there is a common set of psychophysiological changes un-

derlying a variety of trance induction techniques. The differences

that do exist among practitioners with respect to trances illustrate a

polarity between the deliberately induced trance states and those

apparently resulting from psychophysiological predispositions to-

ward entering trance states. The relationship of trance-type labeling

(for example, soul journey/ight, possession) to variables indicative

of temporal lobe discharges and variables assessing social condi-

tions indicates that possession trances are significantly associated

with both symptoms of temporal lobe discharge and with the pres-

cence of political integration beyond the local community.

A PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MODEL.

OF TRANCE STATES,

Ludwig (1966) pointed out that ASCs share features in common,

listing alterations in thinking, change in sense of time and body im-

age, loss of control, change in emotional expression, perceptual di

tortion, change in meaning and significance, a sense of ineffability,

feelings of rejuvenation, and hypersuggestibility. Although there

clearly are psychological and physiological differences associated

with different agents and techniques for entering an ASC (For ex-

ample, EEG differences in meditation and hypnosis [Kasamatsu

and Hirai 1966]), there is evidence that a wide variety of these

trance states share basic characteristics.

Lex (1979) suggested that ritual-induced altered states of con-

sciousness share common physiological features in that they were

designed to (1) permit right hemisphere dominance, (2) achieve cor-

tical synchronization in both hemispheres, and (3) evoke a domi

ant trophotropic (parasympathetic) state. A wide range of trance

induction procedures apparently result in a trophotropic pattern

176 etnos

characterized by parasympathetic discharges, relaxed skeletal mus-

cles, and synchronized cortical rhythms, creating a state more typ-

ical ofright hemisphere dominance. Davidson (1976) also suggested

that the common physiological mechanism underlying a variety of

altered states of consciousness involved extensive ergotropic (sym-

pathetic) activation leading to trophotropic (parasympathetic) col-

lapse.

‘Mandel (1980) provides a more specific physiological mechanism

for explaining the regularities observed by the previous investiga-

tors. He reviews a large number of experimental and clinical studies,

which, he argues, indicate that a wide range of “transcendent

states” are based in a common underlying neurobiochemical path-

way involving a biogenic amine-temporal lobe interaction. This is

manifested in high voltage slow wave EEG activity that originates

the hippocampal-septal area and imposes a synchronous slow

wave pattern on the frontal lobes. A number of agents and proce-

dures invoke this pattern, including hallucinogens, amphetamines,

cocaine, marijuana, polypeptide opiates, long-distance running,

hhunger, thirst, sleep loss, auditory stimuli such as drumming and

chanting, sensory deprivation, dream states, and meditation, Man-

del suggests that there are two bases for temporal lobe hypersyn-

chronous activities, the hippocampal-septal system and the amyg-

dala, Spontaneous discharges originating in the hippocampal-septal

system are referred to as interictal attacks. Spontaneous synchron-

ous discharges originating in the amygdala are more common, and

are generally labeled as temporal lobe epilepsy, or mistakenly schiz~

ophrenia (Mandel 1980).

‘The hippocampal-septal region, which is central to the focus of

brain activity in trance states, is part of the phylogenetically older

part of the brain. It includes terminal projections from the somatic

and autonomic nervous systems, forming part of an extensive sys-

tem of innervation connecting areas of the brain, in particular link-

ing the frontal cortex with the limbic system. This area is central to

basic drives, including hunger and thirst, sex, anger, and the fight/

{light response; it includes the pleasure centers and is the area which

Papez (1937) correctly hypothesized to be the center of emotions.

‘The hypothalamus has direct control over the pituitary, which re-

leases a wide range of neural transmitter substances, including those

similar to hallucinogens and opiates. It also releases substances that

TRANCESTATES 17

act upon the reticular activating system and regulate the sleeping

and waking cycles.

Although these trance states are characterized by the dominance

of activity from evolutionarily earlier parts of the brain, these states

of consciousness are not primitive. The hippocampal formation is

an association area (MacLean 1949); it and associated structures

are central to memory acquisition, storage, and recall. Mandel re-

views research that indicates that the hippocampal slow wave states

are an optimal level of brain activity for energy, orienting, learning,

memory, and attention.

The hypothalamus is considered to be the control center of the

autonomic nervous system, regulating the balance between the sym-

pathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the automatic nervous

system, which regulate body functions in an interactive balance of

activation and deactivation, respectively. The sympathetic nervous

system is the activating system, responsible for the stimulation of the

adrenal medulla and the release of hormones. Activation of the sym-

pathetic nervous system results in diffuse cortical excitation, desyn-

chronization of the EEG, and increased skeletal tone, Activation of

the parasympathetic system leads to decreased cortical excitation

and an increase in hemispheric synchronization. The parasympath-

tic nervous system is evoked by a number of chemical, hormonal,

temperature, and other influences, including direct stimulation in

the 3-8 cycle per second range. Relaxed states also lead to an in-

crease in parasympathetic dominance; closing one’s eyes leads to an

increase in synchronous alpha patterns in the EEG, while anxiety,

arousal, mental effort, and sensory stimulation cause alpha to be re-

placed by desynchronized and mixed waves (Gellhorn and Kiely

1972). Parasympathetic dominant states normally occur only dur-

ing sleep, but trance states frequently involve phases with a para-

sympathetic dominant state as evidenced in collapse and uncon-

sciousness.

In normal states of balance within the autonomic nervous system,

increased activity in one division is balanced by a response in the

other. However, under intense stimulation of the sympathetic sys-

tem, reciprocity breaks down and a collapse of the system into a

state of parasympathetic dominance occurs. Sargant (1974) noted

this pattern of parasympathetic rebound or collapse can lead to era-

sure of previously conditioned responses, changes of beliefs, loss of

memory, and increased suggestibility. Gellhorn (1969) has shown

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- More Squids PDFDocument11 paginiMore Squids PDFBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electron A Photon With Toroidal TopologyDocument25 paginiElectron A Photon With Toroidal Topologycosmodot60Încă nu există evaluări

- Pseudonyms Used by Aleister CrowleyDocument5 paginiPseudonyms Used by Aleister CrowleyBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trithemius' Cipher Decoded Magick Alchemy CryptoDocument28 paginiTrithemius' Cipher Decoded Magick Alchemy Cryptofoggphileas2003100% (3)

- Divination EssayDocument4 paginiDivination EssayBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- On The Operation of Daemons - Pseduo Psellos PDFDocument51 paginiOn The Operation of Daemons - Pseduo Psellos PDFBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Conquest of The IrrationalDocument11 paginiThe Conquest of The IrrationalBobby Black0% (1)

- Exorcism and Enlightenment: Johann Joseph Gassner and The Demons of Eighteenth-Century GermanyDocument22 paginiExorcism and Enlightenment: Johann Joseph Gassner and The Demons of Eighteenth-Century GermanyZachary UramÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Translation of A Zosimos TextDocument11 paginiA Translation of A Zosimos TextaacugnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giordano BrunoDocument224 paginiGiordano BrunoIoana CiocotișanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Of Long-Haired StarsDocument36 paginiOf Long-Haired StarsAbysmalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rose Cross Over The Baltic - ToCDocument3 paginiRose Cross Over The Baltic - ToCBobby Black0% (1)

- Book of Disquiet - Fernando PessoaDocument11 paginiBook of Disquiet - Fernando PessoaBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Putnam, Hilary - What Is Mathematical TruthDocument10 paginiPutnam, Hilary - What Is Mathematical TruthBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Libellus JesuitusDocument14 paginiLibellus JesuitusBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

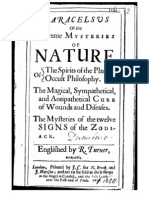

- Archidoxes of Magic of The Supreme Mysteries of Nature-Paracelsus-1655Document94 paginiArchidoxes of Magic of The Supreme Mysteries of Nature-Paracelsus-1655Bobby Black100% (9)

- The Vairocana Bhisam Bodhi SutraDocument320 paginiThe Vairocana Bhisam Bodhi SutraBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book of Games Alfonso X 1283Document65 paginiBook of Games Alfonso X 1283A.Skromnitsky100% (1)

- Surrealist CatalogDocument63 paginiSurrealist CatalogBobby BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rose Cross Over The Baltic - ToCDocument3 paginiRose Cross Over The Baltic - ToCBobby Black0% (1)

- Archidoxes of Magic of The Supreme Mysteries of Nature-Paracelsus-1655Document94 paginiArchidoxes of Magic of The Supreme Mysteries of Nature-Paracelsus-1655Bobby Black100% (9)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- ECON2113 - 1 What Is Economics (Print)Document53 paginiECON2113 - 1 What Is Economics (Print)Michael LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- What We Mean by CreativityDocument18 paginiWhat We Mean by CreativityChris PetrieÎncă nu există evaluări

- BS en 14024-2004 Thermal BreakDocument32 paginiBS en 14024-2004 Thermal BreakGlenn LamboÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACT Crack Geology AnswersDocument38 paginiACT Crack Geology AnswersMahmoud EbaidÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSBSUS601 Ass Task 1 - v2.1Document4 paginiBSBSUS601 Ass Task 1 - v2.1Nupur VermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DRU#1 Engineering Meeting Minutes 12-04-14 - 004Document3 paginiDRU#1 Engineering Meeting Minutes 12-04-14 - 004vsnaiduqcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructions:: Exam Papers Must Not Be Removed From The Exam Room Examiners: R.Russo T.KreouzisDocument9 paginiInstructions:: Exam Papers Must Not Be Removed From The Exam Room Examiners: R.Russo T.KreouziszcaptÎncă nu există evaluări

- SBC 506Document10 paginiSBC 506Amr HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Level Physics Units & SymbolDocument3 paginiA Level Physics Units & SymbolXian Cong KoayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factoring Perfect Square Trinomials: Lesson 4Document29 paginiFactoring Perfect Square Trinomials: Lesson 4Jessa A.Încă nu există evaluări

- Statisticsprobability11 q4 Week2 v4Document10 paginiStatisticsprobability11 q4 Week2 v4Sheryn CredoÎncă nu există evaluări

- UNIT-I Impact of Jet On VanesDocument8 paginiUNIT-I Impact of Jet On VanesAjeet Kumar75% (4)

- Chapter 3 - Optial ControlDocument41 paginiChapter 3 - Optial ControlNguyễn Minh TuấnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Determination of The Capitalization Values For No Load Losses and Load LossesDocument12 paginiDetermination of The Capitalization Values For No Load Losses and Load LossesSaman GamageÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tam2601 Tutorial LetterDocument18 paginiTam2601 Tutorial LetterAnastasia DMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vocabulary AssignmentDocument5 paginiVocabulary Assignmentsimran simranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Plan FLIP FLOPDocument5 paginiProject Plan FLIP FLOPClark Linogao FelisildaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forensic Analysis of GlassDocument9 paginiForensic Analysis of GlassAbrea AbellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Malaysia VBI Full ReportDocument116 paginiMalaysia VBI Full ReportHasoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2 PDFDocument28 paginiChapter 2 PDFDavid SitumorangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Identification of The Best Model and Parameters For T-Y-X Equilibrium Data of Ethanol-Water MixtureDocument7 paginiIdentification of The Best Model and Parameters For T-Y-X Equilibrium Data of Ethanol-Water MixtureMeghana SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lightspeed Oneforma GuidelinesDocument59 paginiLightspeed Oneforma GuidelinesKim Chi PhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promass 63 ManualDocument48 paginiPromass 63 Manualleopoldo alejandro antio gonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salt) Base) : Kantipur Engineering College Dhapakhel, LalitpurDocument3 paginiSalt) Base) : Kantipur Engineering College Dhapakhel, Lalitpursachin50% (2)

- GGCTCDocument7 paginiGGCTCizaizaizaxxx100% (1)

- Navigating The Complexities of Modern SocietyDocument2 paginiNavigating The Complexities of Modern SocietytimikoÎncă nu există evaluări

- GYD Health Gyd Health, Gyd Diagnostics, Diagnostic Centres in Hyderabad India, Diagnostic Centres in Secunderabad India, GDocument1 paginăGYD Health Gyd Health, Gyd Diagnostics, Diagnostic Centres in Hyderabad India, Diagnostic Centres in Secunderabad India, GD.Shiva tejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Layers - of - The - Atmosphere Final Na GrabeDocument23 paginiLayers - of - The - Atmosphere Final Na GrabeJustine PamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF HYDRAULIC POWERPACK AND PUMcalculationsDocument10 paginiDESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF HYDRAULIC POWERPACK AND PUMcalculationssubhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Airhead Meg CabotDocument115 paginiAirhead Meg Cabotdoggybow100% (4)