Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

65 - 43 Pregnancy Related Hypertension

Încărcat de

JackyHarianto0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

4 vizualizări40 paginidasda

Titlu original

65_43 Pregnancy Related Hypertension

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentdasda

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

4 vizualizări40 pagini65 - 43 Pregnancy Related Hypertension

Încărcat de

JackyHariantodasda

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 40

Chapter 43

PREGNANCY-RELATED HYPERTENSION

James M. Roberts, MD

© CLASSIFICATION AND DEFINITIONS

The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy challenge the

medical and obstetric skills of the health care team. Decisions

ws 0 the possible use and appropriate choice of pharmaco-

logic agents require not only an understanding of the patho-

physiology of the hypertensive disorders and a recognition of

the pharmacokinetic changes occurring during pregnancy but

also an appreciation of the possible fetal effects of such ther-

apeutic agents. Obstetric management demands meticulous

maternal observation and use of tests of fetal-placental fune-

tion and fetal maturity in order to weigh maternal risks and

the risks to the infant of intrauterine versus extra

existence.

‘The management of elevated blood pressure (BP) and the

impact of the disorder on the mother and fetus depend on

whether hypertension antedated the pregnancy or appeared as

the marker of pregaancy-specific vasospastic syndrome. An.

attempt to distinguish between the two has led to several

systems of nomenclature and classification. The hypertensive

disorders of pregnancy were for many years

mregnancy, a verm that originally included even hyperemesis

gravidarum and acute yellow atrophy of the liver. This term

reflected the opinion that these disorders had, as a common

etiology, circulating toxins, Failure to identify these toxins did

riot lead to a revision of this terminology, a circumstance

which is indicative of the continuing confusion that has

plagued the taxonomy of these disorders, This archaic rermi-

nology, which neither describes the disorders nor clarifies t

etiology, has rightly been abandoned.

(One of the difficulties in interpreting studies of the hyper-

tensive disorders of pregnancy is the inconsistency of termi-

nology (Rippman, 1969). Several systems of nomenclature are

in use around the world. The system prepared by the National

Institutes of Health (NIH) working group on hypertension in

pregnancy (Gifford et al., 2000a) although as imperfect as all

such systems, has the advantage of clarity and is available in

published form to investigators throughout the world. This

classification is as follows

led toxemias of

& Chronic hypertension

m Preeclampsia-eclampsia

Preeclampsia superimposed upon chronic hypertension

1 Gestational hypertension

The various classifications are explained in the following

discussion,

Chronic Hypertension

Chronic hypertension is defined as hypertension that is

present and observable prior to pregnancy or that is diagnosed

before the 20th week of gestation. Hypertension is defined as a

blood pressure greater than 140/90 mm Hg. Hypertension for

which a diagnosis is confirmed for the first time during preg

nancy, and which persists beyond the 84th day postpartum, is

also classified as chronic hypertension,

Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

The diagnosis of preeclampsia is determined by increased

blood pressure accompanied by proteinuria... Diagnostic blood

pressure increases are either a systolic blood pressure of greater

than of equal to 140 mm Hy or a diastolic blood pressure of

seater than or equal to 90 mm Hg, Diastolic blood pressure is

determined as Krotkoff V (disappearance of sounds), Ie is ec

ommended that gestational blood pressure elevation be

defined on the basis of at least two determinations. The repeat

blood pressure should be performed in a manner that will

reduce the likelihood of artifact and/or patient anxiety

(Gifford et al., 2000b), Absent from the diagnostic criteria ts

the former inclusion of an increment of 30 man Hg systolic or

15 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure, even when absolute values

are below 140/90 mm Hg. This definition was excluded

because the only available evidence shows that women in this

group are not likely to suffer increased adverse outcomes

(North et al,, 1999; Zhang et al., 2001). Nonetheless, women

who have a rise of 30 mm He systolic or 15 mm Hg diastolic

blood pressure warrant close observation, especially if pro-

teinuria and hyperuricemia (uric acid [UA] greater than or

equal t0 6 mg/dL) are also present (Gifford et al., 2000).

Proteinuria is defined as the urinary excretion of 03

protein or greater in a 24-hour specimen. This will usually

correlate with 30 myjdL ("I+ dipstick”) or greater in a random:

urine determination. Because of the discrepancy between

random protein determinations and 24-hour urine protein in

preeclampsia (which can be either higher or lower) (Abuelo,

1992; Kua et al, 1992; Meyer et al., 1994), itis recommended

that the diagnosis be hased on a 24-hour urine specimen if

at all possible of, if this is not feasible, it should be based

fon a timed collection corrected for creatinine excretion

Gifford et al., 2000b).

Preeclampsia occurs as a spectrum but is arbitrarily divided

into mild and severe forms. This terminology is useful for

clescriprive purposes but does not indicate specific diseases, not

859

860 43/Pregnancy-Related Hypertension

should it indicate arbitrary cutoff points for therapy. The diag:

nosis of severe preeclampsia is confirmed when the following

ctiteria are present:

Systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or greater, or diastolic

pressure of 110 mm Hg or greater

2, Proteinuria of 2 g or more in 24 hours (2- or 3-plus on qual-

itative examination)

3. Increased serum creatinine (greater than 1.2 mgldL. unless

known to be previously elevated)

Persistent headache or cerebral or visual disturbances

. Persistent epigastric pair

Platelet count ess then 100,000/mm: and/or evidence of

microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (with increased lactic

acid dehydeogenase)

oat

Eclampsia is the occurrence of seizures in a proeclampric

patient that cannot be attributed to other causes,

Edlema occurs in too many normal pregnant women to be

discriminant and has been abandoned as a marker in

preeclampsia by the National High Blood Pressure Education,

Program (NHBPEP) and by other classification schemes

(Brown et al, 2001; Helewa et al., 1997; Practice, 2002).

Preeclampsia Superimposed

on Chronic Hypertension

There is ample evidence that preeclampsia can occur in

women who ate already hypertensive and that the prognosis

for mother and fetus is much worse for these women than with,

either condition alone. Distinguishing superimposed

preeclampsia from worsening chronic hypertension tests the

skills of the clinician. For clinical management, the principles

of high sensitivity and unavoidable overdiagnosis are appropri-

ate. The suspicion of superimposed preeclampsia mandates

close observation, with delivery indicared by the overall assess-

‘ment of maternal-fetal well being rather than by any fixed end-

point. The diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia is highly

likely with the following findings:

1. In women with hypertension and no proteinuria early in

Pregnancy (prior to 20 weeks’ gestation) and new-onset

proteinuria, defined as the urinary excretion of 0.3 g protein

‘or more in a 24-hour specimen

2. In women with hypertension and proteinuria prior to

20 weeks’ gestation:

a. A sudden increase in proteinuria—urinary excretion of

0.3 g protein or more in a 24-hour specimen, or ewo

dlipstick-test results of 2+ (100 mg/dL), with the values

recorded at least 4 hours apart, with no evidence of

urinary tract infection

b. A sudden increase in blood pressure in a woman whose

blood pressure has previously heen well controlled

«. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count lower

100,000/mm:)

An inctease in ALT or AST to abnormal levels (Gifford

cet al., 2000b)

than

Gestational Hypertension

The woman who has blood pressure elevation detected for

the first time during pregnancy, without proteinuria, is

classified as having gestational hypertension. This nonspecific

term includes women with preeclampsia syndrome who have

not yet manifested proteinuria as well as women who do not

have the syndrome. The hypertension may be accompanied by

other signs of the syndrome, which will influence manage-

ment. The final differentiation chat the woman does not have

preeclampsia syndrome is made only postpartum. If preeclamp-

sia has not developed and blood pressure has returned to

normal by 12 weeks postpartum, the diagnosis of mansient

hypertension of pregnancy can be assigned. If blood pressure ele

vation persists, the woman is diagnosed as having chronic

hypertension. Note that the diagnosis of gestational hypetten-

sion is used during pregnancy only until a more specific din

‘nosis can be assigned postpartum (Gifford et al, 2000b).

Problems with Classification

The degree of blood pressure elevation that constitutes ges-

tational hypertension is controversial. Because average blood

pressure in women in their teens to 208 is 120/60 mim Hy, the

stanclatd definition of hypertension—blood pressure greater

than 140/90 mm Hg—is judged by some investigators to be too

high (Vartran, 1966). This has resulted in the suggestion in the

NHBPEP report that women with increased BP greater than

30 mm Hg systolic or 25 mm He diastolic be observed closely

even if absolute blood pressure has not exceeded 140/90.

There are also problems inherent in the use of blood pres-

sures measured in early pregnancy to diagnose chronte hyper

tension. Blood pressure usually decreases early in pregnat

reaching its nadir at about the stage of pregnancy at which

women usually present for obstetric care (Fig. 43-1). The

decrease averages 7 mm Hyg for diastolic and systolic readings.

In some women, obviously, blood pressure decreases more tha

7 mm Het in others, the early decline and subsequent return of

blood pressure to prepregnant levels in late gestation are

sufficient for a diagnosis of preeclampsia. Women who have

hypertension prior to pregnancy actually experience a greater

decrease in blood pressure in early pregnancy than do nor-

motensive women (Chesley and Annitto, 1947) and thus are

sm Hg

125

Systoe

PARAG

nsf.

10

75|

Diastolic

16 20 24 28 3296 a0

Gestational age (weeks)

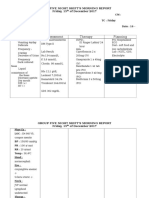

FIGURE 43-1 Mean blood pressure by gastational age in

{8000 Caucasian women 25-24 years of age who delivered singleton

term infants. (From Christianson &, Page EW. Stucies on blood

pressure during pregnancy: Influence at party and age. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 126:509, 1876. Courtesy of the American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

Mig TABLE 42-1. RENAL BIOPSY FINDINGS IN PATIENTS.

43/Pregnancy-Related Hypertension 61

WITH CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF PREECLAMPSIA

Biopsy Findings

Primigravidas (N= 62)

‘Multigravidas (N = 152)

Glomeruloendotheliosis 70%

Normal histologic appearance 5

Chronic renal disease (chronic GTN, chranic pyelonephritis) 255

Asteriolar nephrosclerosis °

GN, gostatenal wophebiastie neoplasia,

1% 4436 (with or without nephrosclerosis)

3% 533%

5% 21%

12%

Mociod rom McCartney CP; Pathological anatomy of acuta hypertension of oregrancy. Coulton 30Supph7, 1064, by permission ofthe Aenican Heart

Associaton Ine

even more likely to be misdiagnosed as preeclamptic according,

co blood pressure criteria.

‘Also, the diagnosis of chronic hypertension based on the

failure of blood pressure to return to normal by 84 days post-

partum can be in error. In a long-range prospective study by

Chesley (1956), many women who remained hypertensive

6 weeks postpartum were normotensive at long-term follow-

up. Even the proteinuria and hypertension are nonspecific

signs, and their presence in pregnancy could be due to condi-

tions other than preeclampsia

Renal biopsy specimens from women with a diagnosis of

preeclampsia (blood pressure increase and proteinuria) demon:

strate these diagnostic difficulties (Table 43-1) (McCartney,

1964). Of 62 women with a diagnosis of preeclampsia in their

fist pregnancies, 70% had a glomerular lesion believed to be

characteristic of the disorder; 24%, however, had evidence of

chronic renal disease that had not been suspected previously

Renal biopsy specimens of multiparous women with a clinical

diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia also demonstrates the

difficulty in diagnosis. Of 152 subjects, only 3% had the char-

acteristic glomerular lesion, but 43% had evidence of preexist-

ing renal or vascular disease.

Preeclampsia has a clinical spectrum ranging from mild to

severe forms and then potentially to eclampsia. Affected

patients do not “catch” eclampsia or the severe forms of

preeclampsia bur rather progress through this spectrum, In

most cases, progression is slow, and the disorder may never

proceed beyond mild preeclampsia. In others, the disease can

progress more rapidly, changing from mild to severe over days

to weeks. In the most serious cases, progression can be fulmi-

nant, with mild preeclampsia evolving to severe preeclampsia

or eclampsia over hours to days

In a series of eclampric women analyzed by Chesley (1978),

25% had evidence of only mild preeclampsia in the days pre-

ceding convulsions. Thus, for purposes of clinical manage-

ment, we must accept the fact that we ate overdiagnosing the

condition because, as discussed lates, a major goal in managing

preeclampsia is the prevention of the serious complications of

preeclampsia and eclampsia, primarily through timing of deli

cry [vis also evident, however, that studies of preeclampsia w'

be confounded by inclusion of women who have been given a

diagnosis of preeclampsia but who actually have another car-”

diovascular or renal disorder.

HELLP

It is quite evident that the pathophysiological changes of

preeclampsia can_be present in the absence of hypertension

and proteinuria. This should not be surprising, as these diag-

nostic criteria are of historical rather than pathophysiological

relevance. Hypertension and proteinuria were the first signs

recognized as predicating preeclampsia (Chesley, 1978)

Understanding this historical evolution presents a challenge to

clinicians and dictates a high index of suspicion in managing

pregnant women with signs and symptoms that could be

explained by reduced organ perfusion. One clear setting in

which this occurs is the HELLP syndrome; the acronym stands

for Hemolysis, Elevated liver enzymes, and Low Platelets. This

seties of findings defines a reasonably consistent syndrome that

has now been studied for over twenty years (Weinstein, 1982),

Although for management purposes it is appropriate to con-

sider HELLP as a variant of preeclampsia, there are differences

in several features of preeclampsia and HELLP that suggest

they could be different entities. Women with HELLP tend to

be older and are more likely to be Caucasian and multiparous

than preeclamptic women; in many cases, they are not hyper

tensive (Egerman and Sibai, 1999). From a pathophysiological

perspective, changes in the renin-angiotensin system charac-

teristic of preeclampsia are not present in HELLP (Bussen

et al., 1998). Nonetheless, the progression of the disease and

its termination with delivery argue for an observation and

management strategy similar to that for preeclampsia. The

serendipitous observation that women who had received

“antepartum steroids appeared ro evidence improvement in the

HELLP syndrome (Magan et al., 1993) stimulated several ret~

rospective and observational studies (Magan and Marcin,

1995; Martin et al., 1997; O'Brien et al., 2000; O'Brien et al.,

2002; Tompkins and Thiagarajah, 1999; Yalcin et al. 1998).

These studies and a small randomized controlled trial (Magan

er al., 1994) suggest improvement in laboratory findings as well

as prolongation of pregnancy. The determination of appropri-

ate dosing and whether the benefit of therapy exceeds risks

await larger, randomized controlled trials.

@ PREECLAMPSIA AND ECLAMPSIA

In spite of che difficulty of making a clinical diagnosis of

preeclampsia, there is no question thac a disorder exists that is

unique to pregnancy, characterized by poor perfusion of many

vital organs (including the fetoplacental unit), and completely

reversible with the termination of pregnancy, Pathologic,

pathophysiologic, and prognostic findings clearly indicate

that this condition, preeclampsia, is not merely an unmasking

of preexisting, underlying hypertension. Although this fact

hhas been well documented for many years, problems still

arise owing to approaches in the management of preeclampsia

that are based solely on principles useful in- managing

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Morning Report 11 April 2019 (Autosaved)Document11 paginiMorning Report 11 April 2019 (Autosaved)JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ni Hms 855012Document16 paginiNi Hms 855012JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morning Report 10 April 2019Document22 paginiMorning Report 10 April 2019JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morning Report: 3 April 2019 Kepaniteraan Ilmu Bedah Fakultas Kedokteran UKI Periode 25 Februari 2019-4 Mei 2019Document12 paginiMorning Report: 3 April 2019 Kepaniteraan Ilmu Bedah Fakultas Kedokteran UKI Periode 25 Februari 2019-4 Mei 2019JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jadwal PosDocument1 paginăJadwal PosJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jadwal PosDocument1 paginăJadwal PosJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morning Report 2 April 2019 (Autosaved)Document15 paginiMorning Report 2 April 2019 (Autosaved)JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 59 - 42 Thromboembolic DiseaseDocument13 pagini59 - 42 Thromboembolic DiseaseJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- SHOCK by DR Robert SP AnDocument22 paginiSHOCK by DR Robert SP AnOchabianconeriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Dr. HendrivanDocument1 paginăTugas Dr. HendrivanJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ophthalmology Record: Dr. Gilbert W. Simanjuntak, SP.M (K)Document6 paginiOphthalmology Record: Dr. Gilbert W. Simanjuntak, SP.M (K)JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 63 - 45 Intensive Care Monitoring of The Critically Ill Pregnant PatientDocument27 pagini63 - 45 Intensive Care Monitoring of The Critically Ill Pregnant PatientJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 DermatotherapyDocument23 pagini01 DermatotherapyMomogi Foreverhappy100% (1)

- Early Warning SignDocument3 paginiEarly Warning SignJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Penjelasan BagusDocument10 paginiPenjelasan BagusJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibu Albine Tanggal 15 Desember Morning ReportDocument4 paginiIbu Albine Tanggal 15 Desember Morning ReportJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibu Syafrima Tanggal 20 Desember Morning ReportDocument4 paginiIbu Syafrima Tanggal 20 Desember Morning ReportJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- TN Rahtomo Tanggal 14 Januari Morning Report (TIM JAGA 5)Document4 paginiTN Rahtomo Tanggal 14 Januari Morning Report (TIM JAGA 5)JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- TN S Hutagaol 19 Januari Morning Report (TIM JAGA 5)Document4 paginiTN S Hutagaol 19 Januari Morning Report (TIM JAGA 5)JackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibu Syafrima Tanggal 20 Desember Morning ReportDocument4 paginiIbu Syafrima Tanggal 20 Desember Morning ReportJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- TN Abdul Wahid Tanggal 25 Desember Morning ReportDocument4 paginiTN Abdul Wahid Tanggal 25 Desember Morning ReportJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibu Sri Endang Tanggal 4 Januari Morning ReportDocument4 paginiIbu Sri Endang Tanggal 4 Januari Morning ReportJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- TN Abdul Wahid Tanggal 25 Desember Morning ReportDocument4 paginiTN Abdul Wahid Tanggal 25 Desember Morning ReportJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)Document38 paginiUrinary Tract Infection (UTI)Trixie Anne GamotinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engkau BesarDocument1 paginăEngkau BesarJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Get AttachmentDocument3 paginiGet AttachmentJackyHariantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)