Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Yale Alumn Magazine Skull Bones

Încărcat de

Anonymous HtDbszqtDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Yale Alumn Magazine Skull Bones

Încărcat de

Anonymous HtDbszqtDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

notebook

Whose skull and bones?

By Kathrin Day Lassila ’81 & Mark Alden Branch ’86

Did Skull and Bones rob the grave of Geronimo

during World War I? For decades, it has been the

most controversial and sordid of all the mysteries

surrounding Yale’s best-known secret society. The

story was widely rumored but, despite the efforts of

reporters and historians and the public complaints

of Apache leaders in the 1980s, never verified. An

internal history of Skull and Bones, written in the

1930s and leaked to the Apache 50 years later, men-

tioned the theft. But Bones spokesmen have always

dismissed the story as a hoax.

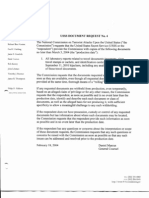

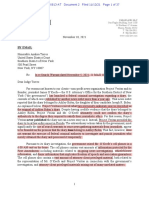

A former senior editor of the Yale Alumni Mag-

azine has now discovered the only known contem-

porary evidence: a reference in private correspon-

dence from one senior Bonesman to another. The

letter was written on June 7, 1918, by Winter Mead

’19 to F. Trubee Davison ’18. It announces that the

remains dug up at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, by a group

that included Charles C. Haffner Jr. ’19 (a new mem-

ber, or “Knight”), have been deposited in the society’s

headquarters (the “Tomb”): “The skull of the worthy

Geronimo the Terrible, exhumed from its tomb at

Fort Sill by your club & the K—t [Knight] Haffner, is

now safe inside the T— [Tomb] together with his well

worn femurs[,] bit & saddle horn.”

Mead was not at Fort Sill, so his letter is not proof.

And if the Bonesmen did rob a grave, there’s rea-

son to think it may have been the wrong one. But

the letter shows that the story was no after-the-fact

rumor. Senior Bonesmen at the time believed it. “It

adds to the seriousness of the belief [that the theft

took place], certainly,” says Judith Schiff, the chief

research archivist at Sterling Memorial Library, who

has written extensively on Yale history. “It has a very

strong likelihood of being true, since it was written

so close to the time.” Members of a secret society,

she points out, were required to be honest with each

other about its affairs.

Moreover, the yearbook entries for Haffner, Mead,

and Davison confirm that they were all Bonesmen.

(The membership of the societies was routinely pub-

lished in newspapers and yearbooks until the 1970s.)

ya l e u n i v e r s i t y l i b r a r y m a n u s c r i p t s a n d a r c h i v e s

Haffner’s entry confirms that he was at the artillery

school at Fort Sill some time between August 1917

and July 1918.

Marc Wortman, a writer and former senior editor

of this magazine, discovered the letter in the Sterling

Memorial Library archives while researching Davi-

son’s war years for a book—The Millionaires’ Unit,

released this month by PublicAffairs press—about

Yale’s World War I aviators. The letter is preserved

in a folder of 1918 correspondence in one of the 16

20 yale alumni magazine | may/june 2006 ©2006 Yale Alumni Magazine

ists, the Bones representatives produced a display

case like the one in the photo. But they told Anderson

that the skull inside it was that of a ten-year-old boy.

They offered the skull to Anderson, but he declined,

as he believed it was not the same one in the photo.

Some researchers have concluded that the Bones-

men could not have even found Geronimo’s grave in

1918. David H. Miller, a history professor at Cam-

eron University in Lawton, Oklahoma, cites his-

torical accounts that the grave was unmarked and

overgrown until a Fort Sill librarian persuaded local

Apaches to identify the site for him in the 1920s. “My

assumption is that they did dig up somebody at Fort

boxes of the F. Trubee Davison Papers. Mead’s was Sill,” says Miller. “It could have been an Indian, but it

one of many letters Davison received that year about probably wasn’t Geronimo.”

Bones matters. With the war on, the Bonesmen were Mead’s letter, written from one Bonesman to

scattered around the United States and Europe, and another just after the incident would have occurred,

society business like choosing new members had to

be conducted by mail. “Lists of people to be tapped

would come to Trubee and he would comment on

them,” says Wortman. Mead’s letter also relays the

The letter shows that the story

news that Parker B. Allen ’19 had been initiated as was no after-the-fact rumor.

a member in Saumur, France, and Allen’s yearbook

entry confirms his membership in Bones and his

Bonesmen at the time believed it.

posting to artillery school in Saumur.

the geronimo rumor first came to wide pub- A recently discovered letter

lic attention in 1986. At the time, Ned Anderson, to F. Trubee Davison ’18

then chair of the San Carlos Apache Tribe in Ari- (top, left) from Winter

zona, was campaigning to have Geronimo’s remains Mead ’19 (top, right) seems

to confirm the rumor that

moved from Fort Sill—where he died a prisoner of Skull and Bones members

war in 1909—to Apache land in Arizona. Anderson plundered the grave of the

received an anonymous letter from someone who Apache warrior Geronimo

claimed to be a member of Skull and Bones, alleg- (left) and brought his skull

ing that the society had Geronimo’s skull. The writer to their “Tomb” in New

Haven. The letter (far left)

included a photograph of a skull in a display case and begins with a discussion of

a copy of what is apparently a centennial history of new members: “Knights”

Skull and Bones, written by the literary critic F. O. (initiates), including

Matthiessen ’23, a Skull and Bones member. In Mat- Charles C. Haffner Jr. ’19,

thiessen’s account, which quotes a Skull and Bones had visited Mead to give

“dope” (information) about

log book from 1919, the skull had been unearthed by possible candidates. Mead

six Bonesmen—identified by their Bones nicknames, also mentions that Parker

including “Hellbender,” who apparently was Haff- B. Allen ’19 had been

ner. Matthiessen mentions the real names of three initiated at Saumur, France.

of the robbers, all of whom were at Fort Sill in early The rest of the letter (not

shown) speculates on the

1918: Ellery James ’17, Henry Neil Mallon ’17, and whereabouts of Haffner’s

courtesy libr ary of congress

Prescott Bush ’17, the father and grandfather of the Army unit.

U.S. presidents.

Anderson arranged a meeting with Bones alumni

Jonathan Bush ’53, a son of Prescott Bush; and Endi-

cott Peabody Davison ’45, a son of Trubee Davison.

At the meeting, Anderson has told several journal-

©2006 Yale Alumni Magazine yale alumni magazine | may/june 2006 21

notebook

suggests that society members had robbed a grave time, says Gaddis Smith, Larned Professor of His-

and had a skull they believed was Geronimo’s. It does tory emeritus, who is writing a history of Yale since

not speak to whether Skull and Bones may still have 1900, “there was a racial consciousness and a sense of

such a skull today. Many have speculated that they Anglo-Saxon superiority above all others.” He notes

do, but there is no direct evidence. Alexandra Rob- that James Rowland Angell, who became president

bins ’98, who wrote the 2002 Bones exposé Secrets of Yale in 1921, “would say, very explicitly, that we

of the Tomb, says she persuaded a number of Bones must preserve Yale for the ‘old stock.’” Smith adds,

alumni to talk to her for her book. “Many talked “The slogan of the first major fund-raising campaign

about a skull in a glass case by the front door that for Yale, in 1926, was ‘Keep Yale Yale.’ The alumni

they call Geronimo,” Robbins told the alumni mag- knew exactly what it meant.”

azine. (Representatives of Skull and Bones did not At the same time, many of those complicit in what

return calls from the magazine by press time.) was apparently the desecration of a grave cherished

Alleged grave robbers,

ideals of service and fellowship, and had lived up to

clockwise from top left: them by enlisting for the war voluntarily. A striking

Prescott Bush ’17, Charles example is chronicled in Marc Wortman’s book, The

C. Haffner ’19, Henry Millionaires’ Unit, which began as an article for this

Neil Mallon ’17, and Ellery magazine about a group of Yale undergraduates who

James ’17. Haffner, who

is credited with the theft

took up the new sport of aviation in order to fight for

of Geronimo’s skull in the the Allies (“Flight to Glory,” November/December

recently discovered letter,

went on to become a

general in World War II and

then chair of the printing Many of those complicit in what

company R. R. Donnelly

& Sons. A purported Skull was apparently the desecration of

and Bones account of the

theft, leaked in the 1980s,

a grave cherished ideals of service

identifies the other three

by name. Bush became a

and fellowship and had enlisted

Connecticut businessman, for the war voluntarily.

a U.S. senator, and the

father and grandfather

of two U.S. presidents.

Mallon became chair of the 2003). Trubee Davison was the co-founder and mov-

oilfield service company

Dresser Industries and the

ing spirit of this project. Before the United States

first employer of George had even entered the war, he recruited two dozen

H. W. Bush ’48. James elite and wealthy young Yalies of his set—five of them

was a banker with Brown Bonesmen—to devote themselves to flying. Out of

Brothers Harriman until his these efforts grew the first squadron in what is today

untimely death in 1932.

the Naval Air Reserve.

Skull and Bones and other Yale societies have The letter might not have been discovered if Davi-

a reputation for stealing, often from each other or son hadn’t founded the aviation group. It might not

from campus buildings. Society members report- even have been written if he hadn’t endured great

edly call the practice “crooking” and strive to outdo personal suffering for the war effort. Davison never

each other’s “crooks.” And the club is also thought to made it overseas; he crashed during a training flight

use human remains in its rituals. In 2001, journalist and was disabled for the rest of his life.

Ron Rosenbaum ’68 reported capturing on video- It was while he was recuperating at home that his

tape what appeared to be an initiation ceremony in fellow Bonesmen wrote to him about candidates for

the society’s courtyard, in which Bonesmen carried membership, initiations abroad, and other society

skulls and “femur-sized bones.” business. The Geronimo letter, with its matter-of-

fact reports of troop units and its boast about a grave

it may have been easier for the bonesmen to robbery, speaks to the complex and contradictory

plunder an Apache’s grave if they shared the racial mores of the privileged class in early twentieth-cen-

attitudes typical of their era and social class. At the tury America.

22 yale alumni magazine | may/june 2006 ©2006 Yale Alumni Magazine

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Iran-Contra: President Reagan's MotivesDocument5 paginiIran-Contra: President Reagan's MotivesElena LazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Too Big To Believe - Massive Scandal Is Brewing at The FBI - Zero HedgeDocument3 paginiToo Big To Believe - Massive Scandal Is Brewing at The FBI - Zero Hedgepaulsub63Încă nu există evaluări

- Iran-Contra Affair TimelineDocument1 paginăIran-Contra Affair TimelineAra JohnsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary of Judy Mikovits & Kent Heckenlively's Plague of CorruptionDe la EverandSummary of Judy Mikovits & Kent Heckenlively's Plague of CorruptionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who Is The Beast - The Beasts of RevelationDocument24 paginiWho Is The Beast - The Beasts of RevelationNATIBOY256Încă nu există evaluări

- 9-11 and The North American Military-Industrial ComplexDocument98 pagini9-11 and The North American Military-Industrial ComplexJeffrey HidalgoÎncă nu există evaluări

- T5 B69 Tampa Flights FDR - All Media Reports in FDR - 1st Pgs For Reference 656Document39 paginiT5 B69 Tampa Flights FDR - All Media Reports in FDR - 1st Pgs For Reference 6569/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9 11 ReleaseDocument9 pagini9 11 Releasewhilimena100% (2)

- Undisputed Facts Point To The Controlled Demolition of WTC 7Document4 paginiUndisputed Facts Point To The Controlled Demolition of WTC 7vishnuprasad4292Încă nu există evaluări

- 14 Facts About 911Document1 pagină14 Facts About 911Lin CornelisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memo of 9/11 Commission Interview of Former Official at US Consulate in JeddahDocument8 paginiMemo of 9/11 Commission Interview of Former Official at US Consulate in Jeddah9/11 Document Archive100% (1)

- President Donald Trump's Davos AddressDocument6 paginiPresident Donald Trump's Davos AddressMasha RadkoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRISM (Prime Radiant and Integrated Simulation Module) - Prime Radiant Device ObamaDocument25 paginiPRISM (Prime Radiant and Integrated Simulation Module) - Prime Radiant Device ObamaBryan Steven González ArévaloÎncă nu există evaluări

- John B Poindexter, Obama, Scalia, MUELLER Just Raw Data For NowDocument167 paginiJohn B Poindexter, Obama, Scalia, MUELLER Just Raw Data For NowDGB DGBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brussels Unveils Sweeping Plan To Cut EU's Carbon Footprint: Ringing Hollow Questions of Trust French ConnectionDocument20 paginiBrussels Unveils Sweeping Plan To Cut EU's Carbon Footprint: Ringing Hollow Questions of Trust French ConnectionHoangÎncă nu există evaluări

- T5 B24 Copies of Doc Requests File 1 - 3 of 3 FDR - USSS Tab - Entire Contents - Secret Service Doc Request 4Document2 paginiT5 B24 Copies of Doc Requests File 1 - 3 of 3 FDR - USSS Tab - Entire Contents - Secret Service Doc Request 49/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- GlaxoSmithKline CIA 6-22-12Document122 paginiGlaxoSmithKline CIA 6-22-12DLDLegalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2023-07-25 House Judiciary To MayorkasDocument3 pagini2023-07-25 House Judiciary To MayorkasFox NewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- J. Edgar Hoover and The Red Summer of 1919 PDFDocument22 paginiJ. Edgar Hoover and The Red Summer of 1919 PDFAlternative ArchivistÎncă nu există evaluări

- America's Vote at RiskDocument36 paginiAmerica's Vote at RiskLisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memorandum To Benard Berelson 1969-EUGENISME PREUVEDocument1 paginăMemorandum To Benard Berelson 1969-EUGENISME PREUVEcruxsacraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Society Foundations 2018-11-07 Budget OverviewDocument13 paginiOpen Society Foundations 2018-11-07 Budget OverviewscribdcrawlerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary: : Red -Handed by Peter Schweizer: How American Elites Get Rich Helping China WinDe la EverandSummary: : Red -Handed by Peter Schweizer: How American Elites Get Rich Helping China WinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The FBI Hand Behind Russia-GateDocument13 paginiThe FBI Hand Behind Russia-GateLGmnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protocols of The Learned Elders of Islam Si'ra 3Document82 paginiProtocols of The Learned Elders of Islam Si'ra 3Ali Akbar KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Senate Report On CIA PracticesDocument525 paginiSenate Report On CIA PracticesbosbydpoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report - The Devastating Costs of DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas' Open Borders PoliciesDocument82 paginiReport - The Devastating Costs of DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas' Open Borders PoliciesDaily Caller News Foundation100% (1)

- John Foster Dulles and The Federal Council of Churches, 1937-1949Document279 paginiJohn Foster Dulles and The Federal Council of Churches, 1937-1949Marcos Reveld100% (1)

- E. Howard Hunt ArticlesDocument19 paginiE. Howard Hunt ArticlesAlan Jules WebermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mystery Death of President KennedyDocument9 paginiMystery Death of President Kennedymikeag09Încă nu există evaluări

- Hiller Hitler and Nazis Were FakedDocument48 paginiHiller Hitler and Nazis Were FakedScott TÎncă nu există evaluări

- White Papers (Skull and Bones) - by Goldstein & SteinbergDocument37 paginiWhite Papers (Skull and Bones) - by Goldstein & SteinbergjrodÎncă nu există evaluări

- State of Montana-Eli Lilly/Zyprexa Lawsuit Fact SheetDocument1 paginăState of Montana-Eli Lilly/Zyprexa Lawsuit Fact SheetBozeman Daily ChronicleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Society Foundation Activity ReportDocument59 paginiOpen Society Foundation Activity ReportSerdat FenadalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- D&A: 23012017 The Barack Obama, Joe Biden Scheme To Entrap General FlynnDocument4 paginiD&A: 23012017 The Barack Obama, Joe Biden Scheme To Entrap General FlynnD&A Investigations, Inc.Încă nu există evaluări

- US Executive Order 13884Document3 paginiUS Executive Order 13884Michael Zhang100% (1)

- Israel - An 'Underwater' Nuclear Power (Thanks To German Submarines) PDFDocument8 paginiIsrael - An 'Underwater' Nuclear Power (Thanks To German Submarines) PDFNaim Tahir Baig100% (1)

- History of Internet PDFDocument47 paginiHistory of Internet PDFSadiqKannerÎncă nu există evaluări

- International: Documents Reveal Top NSA Hacking UnitDocument4 paginiInternational: Documents Reveal Top NSA Hacking UnitEb OlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Have Mossad Death Squads Been Activated in The USDocument1 paginăHave Mossad Death Squads Been Activated in The USThorsteinn ThorsteinssonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tribe/Olson 'Natural Born Citizen' MemoDocument3 paginiThe Tribe/Olson 'Natural Born Citizen' MemoLorenCollinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blackrock and Gates Big Tech OwnershipDocument11 paginiBlackrock and Gates Big Tech OwnershipsatelightÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bilderberg GroupDocument10 paginiBilderberg GroupAnne EnricaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Table Showing Visa Issuances To 9/11 HijackersDocument1 paginăTable Showing Visa Issuances To 9/11 Hijackers9/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tyson - Target America - The Influence of Communist Propaganda On The US Media (1983) PDFDocument143 paginiTyson - Target America - The Influence of Communist Propaganda On The US Media (1983) PDFarge_deianiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- HR 7307 (2) Mortgage Reform LegislationDocument8 paginiHR 7307 (2) Mortgage Reform LegislationSteve SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinton Blood+trailDocument14 paginiClinton Blood+trailVince Romano100% (1)

- Deletion Codes For 9/11 Task Force From 9/11 Commission's FilesDocument1 paginăDeletion Codes For 9/11 Task Force From 9/11 Commission's Files9/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hillary's Husband Re-Elected - The Clinton Marriage of Politics and PowerDocument6 paginiHillary's Husband Re-Elected - The Clinton Marriage of Politics and PowerAdrian BarryÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1st Great AwakeningDocument2 pagini1st Great Awakeningapi-236043597Încă nu există evaluări

- Political Institutions of The Dutch RepublicDocument16 paginiPolitical Institutions of The Dutch RepublicSorin CiutacuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operation Mockingbird PDFDocument7 paginiOperation Mockingbird PDFdamien_lucasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re James O'Keefe Nov 2021 S&SW Special MasterDocument37 paginiRe James O'Keefe Nov 2021 S&SW Special MasterFile 411Încă nu există evaluări

- Jewishpoliceinformersinthe ATLANTICWORLD, 1880-1914: Charlesvanonselen University of PretoriaDocument26 paginiJewishpoliceinformersinthe ATLANTICWORLD, 1880-1914: Charlesvanonselen University of PretoriaAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rapid Decay of Anti-Sars-Cov-2 Antibodies in Persons With Mild Covid-19Document2 paginiRapid Decay of Anti-Sars-Cov-2 Antibodies in Persons With Mild Covid-19Anonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organigramme Eveques Nuc 2Document2 paginiOrganigramme Eveques Nuc 2Anonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organigramme Eveques SedevacantistesDocument5 paginiOrganigramme Eveques SedevacantistesAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Goals-Based Application of Fragility Detection Theory: Knowing What To Worry AboutDocument7 paginiA Goals-Based Application of Fragility Detection Theory: Knowing What To Worry AboutAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Connecting To The Great Rabbinic Families Through Y-DNA: A Case Study of The Polonsky Rabbinical LineageDocument8 paginiConnecting To The Great Rabbinic Families Through Y-DNA: A Case Study of The Polonsky Rabbinical LineageAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Society of Biblical Literature Journal of Biblical LiteratureDocument3 paginiThe Society of Biblical Literature Journal of Biblical LiteratureAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Position Papers 1 - 33 PDFDocument303 paginiPosition Papers 1 - 33 PDFAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using The Kelly Criterion For Investing: William T. Ziemba and Leonard C. MacleanDocument18 paginiUsing The Kelly Criterion For Investing: William T. Ziemba and Leonard C. MacleanAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Between Judaism and FreemasonryDocument28 paginiBetween Judaism and FreemasonryAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gov Uscourts DCD 204569 29 7 PDFDocument35 paginiGov Uscourts DCD 204569 29 7 PDFAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 1 1 904 5220 PDFDocument255 pagini10 1 1 904 5220 PDFAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 6: Time Series 1: LibraryDocument10 paginiLesson 6: Time Series 1: LibraryAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Violent Spiritual Engineering in PitestiDocument49 paginiThe Violent Spiritual Engineering in PitestiAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vladimir Lossky Negative Theology and The Knowledge of God According To Meister EckhartDocument1 paginăVladimir Lossky Negative Theology and The Knowledge of God According To Meister EckhartAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- CLR 2 Review of SpitznagelDocument8 paginiCLR 2 Review of SpitznagelAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letter From Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi To Winston Churchill (19 December 1947)Document2 paginiLetter From Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi To Winston Churchill (19 December 1947)Anonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Statement Type and Repetition On Deception DetectionDocument11 paginiThe Effect of Statement Type and Repetition On Deception DetectionAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Massoni Chapters 1 To 9Document24 paginiMassoni Chapters 1 To 9Anonymous HtDbszqt100% (1)

- Ancient Rome: A Genetic Crossroads of Europe and The MediterraneanDocument8 paginiAncient Rome: A Genetic Crossroads of Europe and The MediterraneanAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organization: Regional ... ,.Document40 paginiOrganization: Regional ... ,.Anonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petritsi's Preface To PsalmsDocument42 paginiPetritsi's Preface To PsalmsAnonymous HtDbszqtÎncă nu există evaluări

- EVELYNDocument3 paginiEVELYNJunalynLynzkieMugotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tools For Implementing Distance Learning During The War (In Ukraine)Document14 paginiTools For Implementing Distance Learning During The War (In Ukraine)mohamed elkubtiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2presentation 4Document19 pagini2presentation 4Reniljay abreoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homework Lesson 20Document4 paginiHomework Lesson 20Quân LêÎncă nu există evaluări

- DHS Meghalaya Nursing Recruitment NotificationDocument2 paginiDHS Meghalaya Nursing Recruitment NotificationDeepak SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment ON Intensive and Extensive Reading Activities: Submitted By, S.V. Allan Sharmila, REG. NO: 19BDEN04Document7 paginiAssignment ON Intensive and Extensive Reading Activities: Submitted By, S.V. Allan Sharmila, REG. NO: 19BDEN04AntoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizal Ateneo and UstDocument32 paginiRizal Ateneo and UstLeojelaineIgcoy0% (2)

- Making A Collage: Independent Reading Project: CategoryDocument5 paginiMaking A Collage: Independent Reading Project: CategoryLian ValenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 8 BCO 1st QuarterDocument11 paginiGrade 8 BCO 1st Quarterharvey unayan100% (1)

- Sanad Verification Form Maharahstra Goa 2024Document5 paginiSanad Verification Form Maharahstra Goa 2024BhargavÎncă nu există evaluări

- QuizDocument8 paginiQuizCharlynjoy AbañasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lauren Williams English 1101x Jan Rieman 2/10/2010 Critical InterpretationDocument5 paginiLauren Williams English 1101x Jan Rieman 2/10/2010 Critical Interpretationlwill201Încă nu există evaluări

- Human Sciences Methods and ToolsDocument41 paginiHuman Sciences Methods and ToolsFaiz FuadÎncă nu există evaluări

- College of Mary Immaculate: J. P. Rizal, Pandi, BulacanDocument36 paginiCollege of Mary Immaculate: J. P. Rizal, Pandi, BulacanTor TorikoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Committee Action PlanDocument4 paginiResearch Committee Action PlanEmenheil Earl EdulsaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Difficulties in Building MeasurementDocument8 paginiLearning Difficulties in Building MeasurementThanveerÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Multitasking of Elementary Teachers and Their Effect in The ClassroomDocument14 paginiThe Multitasking of Elementary Teachers and Their Effect in The Classroommansikiabo100% (2)

- Hyderabad Educators Form - 1 (Responses) - Sheet9Document9 paginiHyderabad Educators Form - 1 (Responses) - Sheet9aruna.sharawatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application Form: Professional Regulation CommissionDocument1 paginăApplication Form: Professional Regulation CommissioncielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maci Sorensen: TJ Maxx, Riverton, Utah - Sales Associate and CashierDocument2 paginiMaci Sorensen: TJ Maxx, Riverton, Utah - Sales Associate and Cashierapi-441232269Încă nu există evaluări

- ECO 112 - Course Outline-2020 - 2021Document5 paginiECO 112 - Course Outline-2020 - 2021Kealeboga WirelessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affiliative Objects: Lucy SuchmanDocument21 paginiAffiliative Objects: Lucy SuchmanpeditodemonofeoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 - Case Study - We Do Not Need A Standard MethodologyDocument5 paginiModule 3 - Case Study - We Do Not Need A Standard MethodologyFahim KazmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- (2021, May 6) - Florence Nightingale. Biography. NightingaleDocument6 pagini(2021, May 6) - Florence Nightingale. Biography. Nightingale김서연Încă nu există evaluări

- Idiomatic ExpressionsDocument18 paginiIdiomatic ExpressionsHazel Mae Herrera100% (1)

- Treasure Plus Secondary Book 2B Unit 6 ADocument41 paginiTreasure Plus Secondary Book 2B Unit 6 AFarzeen MehmoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Motivation Concepts and Their ApplicationsDocument44 pagini4 Motivation Concepts and Their ApplicationsAgatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership TNA QuestionnaireDocument5 paginiLeadership TNA QuestionnaireNilay Jogadia100% (2)

- COT Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiCOT Lesson PlanRichel Escalante MaglunsodÎncă nu există evaluări

- NTSE Stage II Sample Paper - MAT PDFDocument6 paginiNTSE Stage II Sample Paper - MAT PDFDatta NawadikarÎncă nu există evaluări