Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Investigacion Medica de Baja Calidad

Încărcat de

LIC. CRODRIGUEZDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Investigacion Medica de Baja Calidad

Încărcat de

LIC. CRODRIGUEZDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

COMMENTARIES

6. Smith R. Opening up BMJ peer review. BMJ. 1999; Rennie D. Does masking author identity improve peer Available at: http://www.research.att.com/~amo/doc

318:4-5. review quality? a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. /tragicloss.txt. Accessed May 13, 2002.

7. Rennie D. Anonymity of reviewers. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;280:240-242. 16. Harnad S. Implementing peer review on the net:

1994;28:1142-1143. 12. van Rooyen S, Godlee F, Evans S, Black N, Smith scientific quality control in scholarly electronic jour-

8. McNutt RA, Evans AT, Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. R. Effect of open peer review on quality of reviews nals. In: Peek R, Newby G. Scholarly Publishing: the

The effects of blinding on the quality of peer review. and on reviewers’ recommendations: a randomised Electronic Frontier. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1995.

JAMA. 1990;263:1371-1376. controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;318:23-27. 17. Ginsparg P. Creating a global knowledge net-

9. Godlee F, Gale CR, Martyn CN. Effect on the qual- 13. Walsh E, Rooney M, Appleby L, Wilkinson G. work. Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com

ity of peer review of blinding reviewers and asking them Open peer review: a randomised controlled trial. Br J /1417-8219/1/9. Accessed May 13, 2002.

to sign their reports: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry. 2000;176:47-51. 18. Gura T. Peer review unmasked. Nature. 2002;

JAMA. 1998;280:237-240. 14. van Rooyen S, Black N, Godlee F. Development 416:258-260.

10. van Rooyen S, Godlee F, Evans S, Smith R, Black of the review quality instrument (RQI) for assessing 19. Godlee F, Jefferson T. Peer Review in Health

N. Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of peer reviews of manuscripts. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999; Sciences. London, England: BMJ Publishing Group;

peer review: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 52:625-629. 1999.

1998;280:234-237. 15. Odlyzko AM. Tragic loss or good riddance? the 20. Altman DG. Poor-quality medical research: what

11. Justice AC, Cho MK, Winker MA, Berlin JA, impending demise of traditional scholarly journals. can journals do? JAMA. 2002;287:2765-2767.

Poor-Quality Medical Research

What Can Journals Do?

Douglas G. Altman, DSc

The aim of medical research is to advance scientific knowledge and hence—

T

HERE IS CONSIDERABLE EVI - directly or indirectly—lead to improvements in the treatment and preven-

dence that many published re-

tion of disease. Each research project should continue systematically from

ports of randomized con-

trolled trials (RCTs) are poor previous research and feed into future research. Each project should con-

or even wrong, despite their clear im- tribute beneficially to a slowly evolving body of research. A study should

portance.1 The results of several re- not mislead; otherwise it could adversely affect clinical practice and future

views of published trials are briefly sum- research. In 1994 I observed that research papers commonly contain meth-

marized in TABLE 1. Poor methodology odological errors, report results selectively, and draw unjustified conclu-

and reporting are widespread. sions. Here I revisit the topic and suggest how journal editors can help.

Similar problems afflict other study JAMA. 2002;287:2765-2767 www.jama.com

types. A review of 308 phase 2 trials in

cancer (295 of which were single-arm

studies) found that 250 (81%) did not re- ity of the individual (primary) studies.6 either identify previous studies or place

port an identifiable statistical design. Fur- Reviewers often conclude that the avail- their findings in the context of those

ther, positive findings were reported in able evidence is of poor scientific qual- previous studies.13

48% of designed studies but 70% of stud- ity,7,8 sometimes leading to heated debate

ies with no reported design (P=.003).3 about interpretation.9 Why Are There So Many

Of 40 molecular genetics articles pub- General reviews also find much to be Errors in Medical Articles?

lishedinleadinggeneralmedicaljournals, concerned about. Serious statistical er- Errors in published research articles in-

15 (38%) failed to meet at least 2 of 7 rors were found in 40% of 164 articles dicate poor research that has survived the

methodological standards. The authors published in a psychiatry journal10 and peer-review process. But the problems

wrote:“Withoutsuitableattentiontofun- in 19% of 145 articles published in an arise earlier, so a more important ques-

damental methodological standards, the obstetrics and gynecology journal.11 I tion is, Why are submitted articles poor?

expected benefits of molecular genetic suspect that many basic errors have be- Much research is done without the

testing may not be achieved.”4 come less common, but statistics has be- benefit of anyone with adequate train-

In recent years, systematic reviews come more complex, and there is evi- ing in quantitative methods.14 Many in-

have become common. In these, all reli- dence of frequent misapplication of

able evidence relating to a clinical ques- newer advanced techniques.12 Author Affiliation: Cancer Research UK/NHS Cen-

tre for Statistics in Medicine, Oxford, England.

tion is sought, systematically appraised, Also, when interpreting a study, read- Corresponding Author and Reprints: Douglas G. Alt-

and, if suitable, combined statistically in ers need to know how it relates to ex- man, DSc, Cancer Research UK/NHS Centre for Sta-

tistics in Medicine, Institute of Health Sciences, Old

a meta-analysis.5 A key component is an isting knowledge. Many authors inter- Road, Headington, Oxford OX3 7LF, England (e-mail:

assessment of the methodological qual- pret their findings narrowly, failing to doug.altman@cancer.org.uk).

©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, June 5, 2002—Vol 287, No. 21 2765

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 01/02/2013

COMMENTARIES

nals are scientifically sound, despite

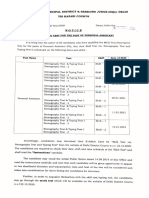

Table 1. Summary of Empirical Evidence of Prevalence of Methodological Problems

in Published Reports of Randomized Trials* much evidence to the contrary. It is im-

Deficiency Evidence portant, therefore, that misleading work

Failing to specify eligibility criteria 25% of 364 reports in surgery journals be identified after publication.

Not reporting an adequate method 68% of 206 reports in obstetrics and gynecology As Gehlbach25 noted, “[t]he ultimate

for generating random numbers journals; 52% of 80 reports in general medical interpretation and decision about the

journals

value of an article rests with the reader.”

Not reporting the mechanism used 89% of 196 reports in rheumatoid arthritis journals; 48%

to allocate interventions of 206 reports in obstetrics and gynecology journals;

Recent draft recommendations from the

44% of 80 reports in general medical journals World Association of Medical Editors say

Failing to state whether blinding was 51% of 506 reports in cystic fibrosis journals; 33% of that “[e]ditors should promote self-

used 196 reports in rheumatoid arthritis journals; correction in science and participate in

38% of 68 reports in dermatology journals

Incorrect analysis of multiple 63% of 196 reports in rheumatoid arthritis journals

efforts to improve the practice of scien-

observations tific investigation by . . . publishing cor-

Inadequate information on harmful 61% of 192 reports in 7 medical areas rections, retractions, and letters critical

consequences of interventions of articles published in their own jour-

Incorrect method of comparison of 58% of 50 reports in general journals nal.”26 Although journals do publish cor-

subgroups

*Data from Altman et al.2

respondence, there are weaknesses in the

way they do so. Most obviously, editors

tific quality, despite the clear ethical select which letters to publish.

Table 2. Time Limit on Submitting Letters

Commenting on Published Articles implications of allowing research that Editors should give special atten-

Time Word is not scientifically valid.19 tion to letters making criticisms of

Journal Limit, wk Limit A further issue is the copying of in- methodology. They should do one of

Annals of Internal Medicine 6 300 correct or inappropriate methods. Once the following: satisfy themselves (per-

BMJ 4 400 incorrect procedures become com- haps by having the letter peer re-

CMAJ 8 250

JAMA 4 400 mon, it can be hard to stop them from viewed) that the criticisms are un-

Lancet 8 500 spreading through the medical litera- founded or unimportant, agree to

New England 4 250

Journal of Medicine ture like a genetic mutation. Many edi- publish the letter and invite the au-

tors have wrestled with the problem of thors to respond, or invite a response

authors objecting to a reviewer’s criti- from the authors and then decide

vestigators are not professional research- cism on the grounds that the same meth- whether to publish. Letters should not

ers; they are primarily clinicians. “. . . [I]f ods have appeared in previous articles, be rejected because of previously pub-

they had any training in research meth- quite possibly by the same authors in the lished correspondence (making differ-

ods it was usually a single course in sta- same journal. Examples of incorrect ent points) or lack of space.

tistics in the first or second year of their practices that persist despite published Time limitation on correspondence

degree, before they really appreciated warnings include using the correlation denies readers the opportunity to draw

how important rigorous research meth- to compare 2 methods of measure- attention to methodological deficien-

ods are in order to do good science.”15 ment,20 using significance tests to com- cies. TABLE 2 shows the current rules of

Also, training in statistics often focuses pare baseline characteristics in random- 6 general medical journals. In effect, there

on data analysis, an emphasis rein- ized trials,21 conducting multiple tests is a statute of limitations by which authors

forced by several statistics textbooks, of- of data recorded at multiple times,22 and of articles in these journals are immune

ten by nonstatisticians, in which design ignoring the clustering in the design and to disclosure of methodological weak-

issues are not addressed.16 Yet study de- analysis of cluster randomized trials.23 nesses once some arbitrary (short) period

sign is a crucial element of education in Peer review can and should weed out has elapsed, which cannot be right.

research methods and appropriately serious methodological errors. How- None of these journals suggests that

forms a key aspect of training in critical ever, expert methodological input is in there are exceptions, but from personal

appraisal generally and evidence-based short supply. Only a third of high- experience, at least 3 of them have occa-

medicine in particular.17,18 impact journals reported statistical re- sionally published letters received beyond

A contributory reason is inadequate view of all published manuscripts.24 The the stated time limit. The BMJ recently

review by research ethics committees vast majority of research is published published a letter pointing out errors in

(institutional review boards). Such re- in low-impact journals where peer re- an article published 6 years earlier. In it,

view should detect studies with impor- view is undoubtedly less thorough. Bland commented: “Potentially incor-

tant flaws in design but clearly often rect conclusions, based on faulty analy-

fails to do so. Unfortunately, commit- Postpublication Peer Review sis, should not be allowed to remain in

tees tend to use a narrow interpreta- Many readers seem to assume that ar- the literature to be cited uncritically by

tion of ethics that downplays scien- ticles published in peer-reviewed jour- others.”27 A time limit discourages poten-

2766 JAMA, June 5, 2002—Vol 287, No. 21 (Reprinted) ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 01/02/2013

COMMENTARIES

tial postpublication peer review; poten- What Journal Editors Can Do Journals can also help improve the

tial correspondents will surely be deterred Authors and editors should have the literature by requiring the full and trans-

by the unambiguous cutoff. Journals with same goals: the advancement of scien- parent reporting of research. Guide-

such a policy should reconsider. tific understanding and improvement in lines have been developed for RCTs,30

A few journals (eg, BMJ and the CMAJ) the treatment and prevention of dis- systematic reviews and meta-analyses

haverapidpublicationofcorrespondence ease. Poor research is the fault of au- of RCTs31 and observational studies,32

on their Web pages. All (or most) letters thors, not journals. Poor research meth- and studies of diagnostic tests,33 and

are published, and there is no apparent ods, unnecessary research, redundant or other initiatives are under way. Edi-

time limit. Nor is there the same limit on duplicate publication, thinly sliced study tors should continue to be involved in

length as in print journals (Table 2). Elec- results, selective reporting, and scien- the development of reporting recom-

tronic letters are linked to the original tific fraud, as well as a general tendency mendations and explicitly require au-

publication and are relatively easily ac- to inflate the importance of the results, thors to follow them.

cessed. It is remarkable and disappoint- should all be resisted vigorously. All Journals can enable and encourage the

ing that as yet so few journals have such could be less likely if research were not publication of research protocols.34-36

a capability. Restricting the facility to cur- a career necessity for physicians. They can use their Web pages to pub-

rentsubscribers,ascurrentlydonebyNeu- Rather than abandon peer review, as lish extended versions of articles. They

rology and Pediatrics, is inadequate. A some have suggested, journals should should also enable and encourage pub-

weakness yet to be resolved is the absence work to strengthen it. In particular, lication of the raw data used in medical

of pressure on authors to respond to criti- methodological review should be imple- research articles (eg, Clinical Chemistry

cisms.28 For such journals there is uncer- mented much more widely. It will never and Neurology). If journals are willing to

tainty about which version is definitive. be possible to eliminate misleading publish data, they should explicitly sug-

Although the BMJ considers bmj.com to studies, but our imperfect peer-review gest this possibility to authors.

be the definitive version,29 only the let- system is a safeguard without which the

ters that appear in the print journal are quality of published research would be Acknowledgment: I thank Iain Chalmers, DSc, and a

indexed on MEDLINE. lower. reviewer for helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

1. Altman DG. The scandal of poor medical re- 13. Clarke M, Alderson P, Chalmers I. Discussion sec- tors (WAME): an agenda for the future. Available at:

search. BMJ. 1994;308:283-284. tions in reports of controlled trials published in gen- http://www.wame.org/bellagioreport_1.htm.

2. Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al, for the eral medical journals. JAMA. 2002;287:2799-2801. Accessed January 20, 2002.

CONSORT Group. The revised CONSORT state- 14. Altman DG, Goodman SN, Schroter S. How sta- 27. Bland M. Fatigue and psychological distress: sta-

ment for reporting randomized trials: explanation and tistical expertise is used in medical research. JAMA. tistics are improbable. BMJ. 2000;320:515-516.

elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663-694. 2002;287:2817-2820. 28. Rennie D. Freedom and responsibility in medi-

3. Mariani L, Marubini E. Content and quality of cur- 15. Chanter DO. Maintaining the integrity of the sci- cal publication: setting the balance right. JAMA. 1998;

rently published phase II cancer trials. J Clin Oncol. entific record: new policy is unlikely to give investigators 280:300-302.

2000;18:429-436. more control over studies [letter]. BMJ. 2002;324:169. 29. Smith R. The BMJ: moving on. BMJ. 2002;324:

4. Bogardus ST Jr, Concato J, Feinstein AR. Clinical 16. Bland JM, Altman DG. Caveat doctor: a grim tale 5-6.

epidemiological quality in molecular genetic re- of medical statistics textbooks. BMJ. 1987;295:979. 30. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D, for the CONSORT

search: the need for methodological standards. JAMA. 17. Sackett DL, Straus S, Richardson WS, Rosenberg Group. The CONSORT statement: revised recom-

1999;281:1919-1926. W, Haynes RB. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to mendations for improving the quality of reports of par-

5. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Sys- Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scot- allel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987-

tematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Con- land: Churchill-Livingstone; 2000. 1991.

text. 2nd ed. London, England: BMJ Books; 2001. 18. Guyatt G, Rennie D, eds. Users’ Guides to the 31. Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie

6. Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Assessing the qual- Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based D, Stroup DF, for the QUOROM Group. Improving

ity of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42-46. Clinical Practice. Chicago, Ill: AMA Press; 2002. the quality of reports of meta-analyses of ran-

7. Hotopf M, Lewis G, Normand C. Putting trials on 19. Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clini- domised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement.

trial—the costs and consequences of small trials in de- cal research ethical? JAMA. 2000;283:2701-2711. Lancet. 1999;354:1896-1900.

pression: a systematic review of methodology. J Epi- 20. Westgard JO, Hunt MR. Use and interpretation 32. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al, for the

demiol Comm Health. 1997;51:354-358. of common statistical tests in method comparison stud- Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiol-

8. Lawlor DA, Hopker SW. The effectiveness of exer- ies. Clin Chem. 1973;19:49-57. ogy (MOOSE) Group. Meta-analysis of observa-

cise as an intervention in the management of depres- 21. Rothman KJ. Epidemiologic methods in clinical tri- tional studies in epidemiology: a proposal for report-

sion: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of als. Cancer. 1977;39(4 suppl):1771-1775. ing. JAMA. 2000;283:2008-2012.

randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2001;322:763-767. 22. Oldham PD. A note on the analysis of repeated 33. The STARD Group. The STARD initiative: to-

9. Olsen O, Gotzsche PC. Cochrane review on screen- measurements of the same subjects. J Chronic Dis. wards complete and accurate reporting of studies on

ing for breast cancer with mammography. Lancet. 1962;15:969-977. diagnostic accuracy. Available at: http://www

2001;358:1340-1342. 23. Donner A, Brown KS, Brasher P. A methodologi- .consort-statement.org/stardstatement.htm. Acces-

10. McGuigan SM. The use of statistics in the Brit- cal review of non-therapeutic intervention trials em- sibility verified May 1, 2002.

ish Journal of Psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167: ploying cluster randomization, 1979-1989. Int J Epi- 34. Horton R. Pardonable revisions and protocol re-

683-688. demiol. 1990;19:795-800. views [commentary]. Lancet. 1997;349:6.

11. Welch GE II, Gabbe SG. Review of statistics usage 24. Goodman SN, Altman DG, George SL. Statisti- 35. Chalmers I, Altman DG. How can medical jour-

in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecol- cal reviewing policies of medical journals: caveat lec- nals help prevent poor medical research? some op-

ogy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1138-1141. tor? J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:753-756. portunities presented by electronic publishing. Lan-

12. Schwarzer G, Vach W, Schumacher M. On the 25. Gehlbach SH. Interpreting the Medical Litera- cet. 1999;353:490-493.

misuses of artificial neural networks for prognostic and ture: A Clinician’s Guide. 3rd ed. New York, NY: 36. Godlee F. Publishing study protocols: making them

diagnostic classification in oncology. Stat Med. 2000; McGraw-Hill; 1993. visible will encourage registration, reporting and re-

19:541-561. 26. Report of the World Association of Medical Edi- cruitment [editorial]. BMC News Views. 2001;2:4.

©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, June 5, 2002—Vol 287, No. 21 2767

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 01/02/2013

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- C3704 2018 PDFDocument122 paginiC3704 2018 PDFHaileyesus Kahsay100% (1)

- Session 12. Facilities layout-IIDocument34 paginiSession 12. Facilities layout-IIsandeep kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5400 Replace BBU BlockDocument15 pagini5400 Replace BBU BlockAhmed HaggarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rating The Quality of Evidence Publication BiasDocument6 paginiRating The Quality of Evidence Publication BiasGeorgina CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Pone 0063221Document4 paginiJournal Pone 0063221PentaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiology: A Proposal For Reporting Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies inDocument6 paginiEpidemiology: A Proposal For Reporting Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies inFahadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resumo Tipos EstudoDocument5 paginiResumo Tipos EstudosusanammÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathogenesis and Treatment of Varicoceles: Controversy Still Surrounds Surgical TreatmentDocument2 paginiPathogenesis and Treatment of Varicoceles: Controversy Still Surrounds Surgical TreatmentFenny LiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproducibility in Science: ReviewDocument12 paginiReproducibility in Science: ReviewRamon CarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peer Review in Health SciencesDocument383 paginiPeer Review in Health SciencesashfaqamarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essential Skills: BJOG Launches The Research Methods Guides: EditorialDocument1 paginăEssential Skills: BJOG Launches The Research Methods Guides: EditorialuzairÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mata 2021Document11 paginiMata 2021Archondakis StavrosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 483531a PDFDocument3 pagini483531a PDFcontact4079Încă nu există evaluări

- Contoh ArtikelDocument6 paginiContoh ArtikelMilka Salma SolemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 806 FullDocument3 pagini806 FullMarli VitorinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Scandal of Poor Medical Research - Altman DDocument6 paginiThe Scandal of Poor Medical Research - Altman DNeita Gil CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Write A Research Paper: EditorialDocument2 paginiHow To Write A Research Paper: EditorialjustinohaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practice For Causal Reasoning Science and Experimental Methods TristanDocument11 paginiPractice For Causal Reasoning Science and Experimental Methods TristanAsif SubhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Importance of Biostatistics To Improve The Quality of Medical JournalsDocument6 paginiImportance of Biostatistics To Improve The Quality of Medical JournalsAnand KasiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raise Standards For Preclinical Cancer ResearchDocument3 paginiRaise Standards For Preclinical Cancer ResearchMiguel CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rating The Quality of Evidence-InconsistencyDocument9 paginiRating The Quality of Evidence-InconsistencyGeorgina CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproducibility of Systematic Literature Reviews On Food Nutritional and Physical Activity and Endometrial CancerDocument9 paginiReproducibility of Systematic Literature Reviews On Food Nutritional and Physical Activity and Endometrial CancerM MuttaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re Produc Ibility and Research Ethics 10312016 CleanDocument13 paginiRe Produc Ibility and Research Ethics 10312016 CleanFelixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bias As A Threat To The Validity of Cancer Molecular-Marker Research David F. RansohoffDocument8 paginiBias As A Threat To The Validity of Cancer Molecular-Marker Research David F. RansohoffHopÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Lesson of Ivermectin: Meta-Analyses Based On Summary Data Alone Are Inherently UnreliableDocument2 paginiThe Lesson of Ivermectin: Meta-Analyses Based On Summary Data Alone Are Inherently UnreliableMayumi Prieto BoccaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public Health and Community Medicine MnemonicsDocument48 paginiPublic Health and Community Medicine MnemonicsSarah89% (19)

- Rating The Quality of Evidence-IndirectnessDocument8 paginiRating The Quality of Evidence-IndirectnessGeorgina CÎncă nu există evaluări

- John M. Yancey - Ten Rules For Reading Clinical Research ReportsDocument7 paginiJohn M. Yancey - Ten Rules For Reading Clinical Research ReportsdanmercÎncă nu există evaluări

- Six Persistent Research Misconceptions - Rothman 2014Document5 paginiSix Persistent Research Misconceptions - Rothman 2014pescando y viajando juan sotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Meta-Analysis in Evidence-Based Medicine: High-Quality Research When Properly PerformedDocument3 paginiThe Meta-Analysis in Evidence-Based Medicine: High-Quality Research When Properly PerformedAdin SuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- StrobeDocument6 paginiStrobeAanh EduardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument11 paginiNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptshazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument8 paginiJurnal InternasionalBerliana Via AnggeliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Observational Studies: Why Are They So ImportantDocument2 paginiObservational Studies: Why Are They So ImportantAndre LanzerÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Bench To WhereDocument5 paginiFrom Bench To WhereLuminita SimionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Random Assignment On Study Outcome: An Empirical ExaminationDocument12 paginiImpact of Random Assignment On Study Outcome: An Empirical ExaminationC NortonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistics in Clinical OncologyDocument563 paginiStatistics in Clinical OncologyvictorcastroolidenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ioannidis 2016Document10 paginiIoannidis 2016Vaida BankauskaiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Randomized Controlled Trial: Gold Standard, or Merely Standard?Document20 paginiThe Randomized Controlled Trial: Gold Standard, or Merely Standard?ShervieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review of Randomized Control TrialsDocument8 paginiLiterature Review of Randomized Control Trialsafmzqlbvdfeenz100% (1)

- Epidemiology: The UninitiatedDocument2 paginiEpidemiology: The UninitiatedHabid OsorioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrative Review of The LiteratureDocument22 paginiIntegrative Review of The Literatureapi-486056653Încă nu există evaluări

- Sessler, Methodology 1, Sources of ErrorDocument9 paginiSessler, Methodology 1, Sources of ErrorMarcia Alvarez ZeballosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risperidone For The Core Symptom Domains of AutismDocument1 paginăRisperidone For The Core Symptom Domains of AutismJacyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic PDFDocument2 paginiBasic PDFAshilla ShafaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article Critique JUNE 26, 2022Document7 paginiArticle Critique JUNE 26, 2022jessicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1988 ColditzDocument10 pagini1988 ColditzgwernÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Economics of Reproducibility in Preclinical Research: Leonard P. Freedman, Iain M. Cockburn, Timothy S. SimcoeDocument9 paginiThe Economics of Reproducibility in Preclinical Research: Leonard P. Freedman, Iain M. Cockburn, Timothy S. SimcoecipinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Methods and Biostatistics in Oncology: Understanding Clinical Research as an Applied ToolDe la EverandMethods and Biostatistics in Oncology: Understanding Clinical Research as an Applied ToolRaphael. L.C AraújoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bias in Medical Research Article AnalysisDocument5 paginiBias in Medical Research Article Analysisselina_kollsÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument16 paginiNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptMarvin BundoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Case For Structuring The Discussion of Scientific PapersDocument2 paginiThe Case For Structuring The Discussion of Scientific PapersAdrian ZazzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors That Influence Validity (1) : Study Design, Doses and PowerDocument2 paginiFactors That Influence Validity (1) : Study Design, Doses and PowerHabib DawarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Current Publication Practices May Distort ScienceDocument5 paginiWhy Current Publication Practices May Distort ScienceTheBoss1234Încă nu există evaluări

- AppendicitisDocument13 paginiAppendicitisASdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liberati2009 PDFDocument34 paginiLiberati2009 PDFMiranti Dea DoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artigo 1Document11 paginiArtigo 1Maria José LimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3.giacomami Users Quides To The MedicalDocument6 pagini3.giacomami Users Quides To The MedicalMayra De LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - Outcomes ResearchDocument12 pagini1 - Outcomes ResearchMauricio Ruiz MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 204 2017 Article 1980Document25 pagini204 2017 Article 1980killi999Încă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Sources of Bias in Diagnostic Accuracy StudiesDocument8 paginiUnderstanding Sources of Bias in Diagnostic Accuracy StudiesNatalia LastraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inter Per Ting Clinical TrialsDocument10 paginiInter Per Ting Clinical TrialsJulianaCerqueiraCésarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 - Holger J Schünemann - GRADEguidelines18HowROBINSIandothertoolstoa...Document10 pagini2018 - Holger J Schünemann - GRADEguidelines18HowROBINSIandothertoolstoa...zenenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coding CarnivalDocument12 paginiCoding CarnivalSuchitra WathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boostherm DWV 01 2017 ENDocument6 paginiBoostherm DWV 01 2017 ENCarlos LehmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 78-00583 Profo Metpoint Ocv Compact 8p Int DisplayDocument8 pagini78-00583 Profo Metpoint Ocv Compact 8p Int DisplayLinh NgoÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOP For Handling of Rejected Raw MaterialDocument6 paginiSOP For Handling of Rejected Raw Materialanoushia alviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Free Space For Shanghair CompressorDocument1 paginăFree Space For Shanghair CompressorAndri YansyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mobilgrease XHP 460Document3 paginiMobilgrease XHP 460Jaime Miloz Masle JaksicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drishtee DevelopmentDocument34 paginiDrishtee Developmenttannu_11Încă nu există evaluări

- Practices For Lesson 3: CollectionsDocument4 paginiPractices For Lesson 3: CollectionsManu K BhagavathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Watershed SegmentationDocument19 paginiWatershed SegmentationSan DeepÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBAM Deployment GuideDocument80 paginiMBAM Deployment GuidePsam Umasankar0% (1)

- P40 Series: Technical SpecificationDocument2 paginiP40 Series: Technical SpecificationHarry HonchoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A1NM Rev 30 TYPE CERTIFICATE DATA SHEET A1NM 767Document16 paginiA1NM Rev 30 TYPE CERTIFICATE DATA SHEET A1NM 767MuseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bibliography of A Series of Publications On Ecology, Environment, Biology. Selected. Http://ru - Scribd.com/doc/238214870Document279 paginiBibliography of A Series of Publications On Ecology, Environment, Biology. Selected. Http://ru - Scribd.com/doc/238214870Sergei OstroumovÎncă nu există evaluări

- BulldogDocument20 paginiBulldogFlorinÎncă nu există evaluări

- TqemDocument3 paginiTqemJudith D'SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adly 50 RS Parts ListDocument50 paginiAdly 50 RS Parts ListZsibrita GyörgyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electronics 19 PDFDocument25 paginiElectronics 19 PDFgitanjali seciÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 Golden Rules of Mobile Testing TemplateDocument36 pagini7 Golden Rules of Mobile Testing Templatestarvit2Încă nu există evaluări

- Mit PDFDocument113 paginiMit PDFAnonymous WXJTn0Încă nu există evaluări

- 1 Starting Time Calculation 2Document15 pagini1 Starting Time Calculation 2Sankalp MittalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labtech 20121120 - SS HIRE Bro C 2Document24 paginiLabtech 20121120 - SS HIRE Bro C 2Carlos PereaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CO2 System ManualDocument11 paginiCO2 System Manualthugsdei100% (1)

- Unit Plan: Economics Educated: Submitted By: Nancy Vargas-CisnerosDocument4 paginiUnit Plan: Economics Educated: Submitted By: Nancy Vargas-CisnerosNancy VargasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patrick C Hall@yahoo - com-TruthfinderReportDocument13 paginiPatrick C Hall@yahoo - com-TruthfinderReportsmithsmithsmithsmithsmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- UTDEC 2020: Sub: Skill Test/Typing Test For The Post of Personal AssistantDocument2 paginiUTDEC 2020: Sub: Skill Test/Typing Test For The Post of Personal Assistantneekuj malikÎncă nu există evaluări

- w170 w190 w230c - 30644gb 123bbDocument20 paginiw170 w190 w230c - 30644gb 123bbJIMISINGÎncă nu există evaluări