Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Kamal Jung Kunwar: Key Words: Payment For Environmental Services, Shivapuri National Park, Upstream and

Încărcat de

kabibhandariDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Kamal Jung Kunwar: Key Words: Payment For Environmental Services, Shivapuri National Park, Upstream and

Încărcat de

kabibhandariDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Payment for Environmental Services in Nepal

(A Case Study of Shivapuri National Park, Kathmandu, Nepal)

Kamal Jung Kunwar1

Abstract

With a view to highlight the issues of Payment for Environmental Services (PES) in

Nepal, the paper aims at providing information on possible environmental goods and

services rendered by the Shivapuri National Park (ShNP), Kathmandu. It also endeavors

to explore the policy issues with regards to PES in Nepal. Secondary information was

obtained through published and unpublished literatures and office records of ShNP

whereas primary information was generated through various Rapid Appraisal tools;

such as informal discussion with park officials, semi-structured interview, field

observation etc.

Despite the ShNP’s role in providing environmental goods and services to the dwellers

of Kathmandu metropolitan, the local inhabitants have not been benefited from such

services. There has been low level of awareness on the issues such as environmental

goods and services and possible benefits to be obtained and its equitable sharing. It is

the dire need that policy should focus on these issues so that all the stakeholders could

be benefited from the conservation and management of protected areas and forests in

the country.

Key Words: Payment for environmental services, Shivapuri national park, Upstream and

downstream relationship, Benefit sharing, Free riders.

Introduction

Environmental services are hydrological services, carbon sequestration, biodiversity services,

recreational services, landscape or scenic beauty. Environmental valuation is largely based on

the assumption that individuals are willing to pay for environmental gains and conversely, are

willing to accept compensation for some environmental losses.

Payment for Environmental Services (PES) is a mechanism to improve the provision of indirect

environmental services in which providers of environmental services receive direct payments

from the users of these services. PES mechanisms are usually implemented for hydrological

services as upstream land uses affect quantity, quality, and timing of water flows downstream.

Service providers and service users (downstream beneficiaries) negotiate on desired land use

practices upstream and the amount of payment to compensate for making such changes.

Wunder (2005) has identified four types of PES that currently stand out: (i) carbon sequestration

and storage (electricity companies are paying farmers for planting and maintaining additional

trees), (ii) biodiversity protection (conservation donors are paying local people for setting aside

1

Assistant environment officer, Ministry of Forest & Soil Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal, kalpa2062@gmail.com

The Initiation 2008 SUFFREC 63

or naturally restoring areas to create a biological corridor), (iii) watershed protection (downstream

water users are paying upstream farmers for adopting land uses that limit deforestation, erosion,

and flooding risks, and (iv) landscape beauty ( a tourism operator is paying a local community

not to hunt in a forest being used for tourists’ wildlife viewing).

According to CIFOR (2002), regeneration of dry secondary forests in central India, could

double carbon sequestration from 27.3 to 55.2 t/ha in ten years at very modest cost. Similarly,

it has also estimated that suitably targeted forest project can produce carbon offset at the

predicated market price of US$ 15-20/ton. In this regard, community forests in Nepal can be

taken as potential carbon sinks to generate substantial income to our Community Forest User

Groups (CFUGs) by selling carbon credit at international markets. (Mararjan, 2004)

Water supplies yield significant financial and economic benefits for downstream users, however,

those benefits need to be identified and valued properly to convince the decision-makers

about importance of managing upper catchments as a part of water supply infrastructure.

Assessment was done to value the water in different uses (hydropower, irrigated agriculture,

urban consumption) and for different users, enabling the financial and economic impacts of

land use change on water service delivery to be calculated (Karna, 2008).

Shivapuri National Park (ShNP) contributes water to over 4,000 ha of agricultural farms.

Water from the Sundarijal sub-catchment is collected into a reservoir and channeled to a

hydropower plant located in Sundarijal that generates about 4,231,000 Kilowatt-hour of

electricity a year. This water is processed and transferred to the city for the distribution to

domestic consumers who use about 33.3 million cubic meters of water a year from this source.

Each of this water uses generating huge financial revenues and economic benefits. Currently,

the net financial value-added across different water uses totals NPR 306 million or some US$

7.65 million a year (Karna, 2008).

Some of the very recent studies are more focused to economic valuation of natural resources

and generating information on feasibility to set up PES mechanism in Nepal. A very recent

one on economic valuation has highlighted the importance of Churia hills resources for local

communities and the importance of Churia watersheds for hydrological benefits to downstream

people, and generated much needed background information for setting up PES schemes.

On the implementation front, a PES like scheme being implemented in Kulekhani hydropower

in Makawanpur District is a very good and pioneering initiative. Kulekhani watershed supplies

water to two hydroelectric plants that generate a total of 92 MW of electricity, and Nepal

Electricity Authority earns revenue from its sale. However, its operation often suffered for

limited availability of water and heavy sedimentation in water reservoir. To address these

issues, Winrock Nepal facilitated the setup and operation of a reward mechanism to upland

communities to motivate them to change their land use patterns. A certain percentage of

hydropower royalty is allocated for the development activities for the upland communities in

this watershed. Land use changes in upland area has visibly resulted in reduced sedimentation

and increased dry season water flow to the reservoir, which in economic terms are estimated

at NPR 3.12 million a year.

Buffer zone programme and conservation area management are others examples of Payment

of environment services of biodiversity conservation and management. Aesthetic and scenic

64 SUFFREC The Initiation 2008

beauty helps to develop eco-tourism in these areas and earning from the tourism development

sharing with local communities for the sake of socio-economic development and livelihoods

support.

Basic and required policies and institutional arrangement for PES schemes are also already in

place. The National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1973, the Local Self Governance

Act 1999, the Electricity Act 1992, the Forest Act 1993, among few others, contain the concept

of benefit sharing (Karna, 2008). In the buffer zone management programs 50% revenue

generated by respective park and reserve directly goes to local communities for their socio-

economic development and biodiversity conservation in Buffer zone.

PES being a new concept and it is a burning issue for Nepal, many stakeholders, service

providers and beneficiaries are not aware of it. Capacity building of concerned organizations

and policy makers is inevitable. Moreover, awareness creation among local communities is

also important.

Methodology

Study site

Shivapuri National Park

(ShNP) is located between

27 o 45' and 27 o 52' north

latitude and 85o 15' and 85o

30' East longitudes. Covering

an area of about 144 sqkm of

Kathmandu, Nuwakot, and

Sindhupalchowk Districts of

Central Development

Region, the park stretches

about 20-24 km from east to

west and about 8-10 km from

north to south.

ShNP is located about 12 km north of Kathmandu. Lying in the middle mountain physiographic

zone, its elevation ranges from 1320 meters above sea level to 2732 masl. The park is rich in

biodiversity with more than 2,000 plant species, 21 mammals and 180 birds, and has also

cultural and livelihoods values for local communities.

Data collection and analysis

Technical and policy documents were extensively reviewed to derive existing information.

Secondary information was obtained through published and unpublished literatures and office

records of ShNP whereas primary information was generated through various Rapid Appraisal

tools; such as informal discussion with park officials, semi-structured interview, field observation

etc.

The Initiation 2008 SUFFREC 65

Collected information was compiled and organized systematically. The data were analyzed

using MS-Excel with frequency and bar diagrams. The descriptive research design was adopted.

Result and Discussions

Socio-economic condition of local communities

z Population

According to 2001 census there are 101,493 people living of ShNP and its buffer zone. About

350 households (Okhareni and Mulkharka villages) are inside the park. This population exhibits

an average household size of 5.5 persons. The dominant ethnic group adjacent to the park is

Tamang, a group that has always been marginalized socially and economically.

z Landholding capacity and occupation

Ownership of land is a powerful cultural and economic significance governing food sufficiency

and livelihoods of the households. The land holding is an average of 0.2 hectares (Khatri-

Chhetri, 1993) in Shivapuri area. Some of the households are either landless or have no land

title.

Agriculture and livestock are still the dominant livelihood patterns for the people of Shivapuri

area as more than 90% of the households are engaged directly or indirectly in these occupations.

Agriculture in the area is characterized by mixed farming enterprise where people cultivate

crops, raise livestock, grow vegetables and transplant fruit trees. However, around half of the

populations are suffering from food deficiency for 4-10 months each year.

z Crop damage and livestock depredation

Invasion of wildlife in the surrounding area has tremendously increased after the designating

Shivapuri as a protected area resulting high crop damage and livestock depredation. The most

destructive wild animal in terms crop damage appears to be wild boar. However, birds, monkeys

and porcupine are also reported as serious pests to crop.

In addition to crop raiding, some isolated cases of livestock depredation by wild animal are also

reported. Common leopard, wildcat and jackal are reported to be the major predators. Due to

excessive pressure on their habitat, there may be some possibilities that the wild animals may

harm to human beings as well.

Environmental goods and services of ShNP

z Water recharge and discharge

Rivers, ponds, marshlands and reservoirs are the major wetlands in this park. Preliminary

survey shows that about 0.24 sqkm (0.17%) is covered by all the wetlands in ShNP. The major

wetlands contributing recharge of the fresh water to Bagmati, Sunkoshi and Trishuli rivers.

66 SUFFREC The Initiation 2008

ShNP area is important for drinking water, irrigation, traditional grindling mills as well as it has

wider scope of ecological value. Detailed studies have yet to be made for northern aspect.

However, southern aspect has 226.7 million litres water discharge per day. It is the worth of

water resources but demand on drinking water for Kathmandu is 140 million litre per day.

And presently collection and supply is only 29.5 million litre per day. Drinking Water

Corporation charged as per litre to the consumer and earning huge amount of money annually.

z Tourism, recreation and aesthetic value

Scenic beauty, historical and religious sites, outdoor adventure like nature-walk, hiking, trekking

and mountain biking, and wildlife-tourism (Bird watching) are some of the potential attractions

of ShNP. Currently, tourism is developed in surrounding of the important religious sites like

Budhanilkantha, Nagi-Gumba, Sundarijal, Bajrayogini and the scenic-spots like Kakani and

Chisapani.

The park is linked by three major road-networks from the valley: Sundarijal, Budhanilkantha,

Tokha and Kakani. Inside the park, there is 95 km graveled road, 83 km foot trails constructed

for trekking and village walks route,

bird watching, and educational tours

to the students

a) No. of tourists

The visitor’s records of ShNP

shows that the park has been

visited by an average of 49,200

visitors annually during last five

years, but in the last year more

than 70,000 tourists visited in the

park. Out of this numbers Nepali

visitors are ten folds higher than the

foreigner.

Source: ShNP, Office record, 2008

b) Revenue collection and

tourism enterprise

The park revenue is accounted only

to entry fee more than 95% and others

sources of revenue collection are

penalties, tender form, forest products

and miscellaneous. Bar diagram

shows that average revenue is NRs.

2.9 millions.

Local people’s involvement in tourism

activities is negligible compared to a Source: ShNP, Office record, 2008

The Initiation 2008 SUFFREC 67

large number of tourists visiting the park. About 11 households hold local lodges, 10 households

hold local restaurants, and 32 households hold teashops. Altogether 150 people were engaged

in these food-based activities.

z Biodiversity

The park harbors 2122 flowering plants (41% out of 5067 identified in Nepal) with 16 endemic

(Shakya et.al, 1997). More than 35 species of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) including

129 species of mushrooms are found in the park. The park comprises mainly four forest types

namely lower mixed hardwood forest, Chirpine forests, upper mixed hardwood forests, Oak

forests (Annon, 1992).

ShNP supports a large number of wildlife species. There are 21 species of mammals out of

nine are threatened species. It harbors 177 species of birds and 14 of them are threatened

including spring babbler, which is an endemic species. There are more than 102 species of

butterflies.

z Land use pattern

The land use pattern in and around ShNP is predominated by forest (40.7%), followed by

agriculture (35.3%), grassland with shrubs (2.6%), landslides (0.5%), settlements, (0.9%),

riverine features (0.2%), and abandoned land (2.0%).

z Religious and cultural value

Shivapuri hill is the most important sanctity and famous from time immemorial. Religiously, it is

respected from both Hinduism and Buddhism. For Hindus, it is an abode of Lord Shiva, and for

Buddhist, it is sanctity for its cultural and religious heritage. It is a Shaktipith- source of spiritual

power, for both religions. For a long time to date this sacred forest has given shelter to countless

learned saints who ultimately found their way to salvation while meditating in this place of

tranquility.

Religiously the water of the Bagmati River is used for holy bath in Bagdwar. The holy water

of Vishnumati in Vishnupaduka is culturally important to take holy bath on the occasion of

New Year of Bikram Sambat.

z Carbon sequestration

Kathmandu city is undergoing catastrophic environmental degradation primarily from air

pollution, which has caused significant number of respiratory related illnesses in the valley’s

resident population. The air pollution caused from burning of fossil fuel leaves a thick cloud of

pollutants, mainly CO2 suspended in the air for a long period until wind or rain disperses it.

In this scenario, ShNP plays a vital role as sink by sequestering carbon from the source and

reducing the time taken to clean the valley’s environment. The valley’s entire population shares

sequestering CO2 by ShNP as an ancillary benefits.

68 SUFFREC The Initiation 2008

z Watershed management

Topography is mostly mountainous with steep slopes of >30% at least in 50% of the total area

of the park. Because of the steep topography and the nature of soil, soil erosion is very high in

places particularly in the northern part of the park. Land slide, gullies, sheet erosion in the

sloping terraces, and stream bank erosion are common all over Shivapuri. Major causes of

such hazards include (a) construction of road on steep southern and northern slopes (b)

overgrazing, and (c) abandoned agriculture land, which is prone to overgrazing and lacks

maintenance of terraces.

Shivapuri is the origin of some important river systems including Bagmati, and Vishumati,

which are the major watersheds. There are some sub-watersheds of small streams including

Rudramati, Yagmati and Dhobi Kholas. Although, Trishuli, Sunkoshi, Bhotekoshi, Indrawati,

Melamchi and Balephi are not within the influence zone of ShNP.

Several catchments covering 42 sqkm within Shivapuri are the main sources of surface and

ground drinking water for the Kathmandu valley. The largest one is Sundarijal catchment

(32.7%), which drains into Bagmati. In total, Shivapuri provides almost 40% of the surface

drinking water, which comes from various sites. The total amount of drinking water tapped

from various sites of Shivapuri is 100-140 million liters/day.

By proper management of watershed flood, landslide and soil erosion is controlled which

helps to reduce property loss and human casualties. Likewise, land productivity is increased

through irrigation and decomposition and deposition of leaf litter. Sedimentation is decreased

and if valuated loss of property, it contributes millions of money not only the local communities

but also the downstream communities.

The Drinking Water Department has neither taken any initiative to protect the water source

area nor provided incentives to communities involved in watershed protection. It is essential

to make a necessary arrangement to plough back certain percent of the drinking water revenue

for conservation efforts and livelihood support activities in the area. The up-stream area should

be strictly protected for a continuous flow of drinking water to the Kathmandu city.

z Community forests and resource dependency

Access to common property resources, particularly forests is vital to the livelihood of the

rural communities throughout the country. And people’s reliance on ShNP forest is not

exceptional. Lack of alternatives, people’s dependency on park forests especially for firewood,

fodder, timber and grazing space is still continued.

As the economy is predominately agro-based, dependency on forest has become imperative.

One of the reasons of high dependency on park forest is that forest resources outside the park

is poorly developed and alternative sources of energy are either not available or are costly for

the poor people. Hence, people are forced to enter the park and compelled to use forest

resources. Total population affected by or dependent on the park is 95,837 from 18,235

households in and around ShNP. Dependent population per sq km of the park is 666 persons

(NARM, 2004).

The Initiation 2008 SUFFREC 69

About 20 Community Forests (CFs) in Kathmandu and 10 CFs in Nuwakot have been handed

over to communities by respective DFOs but they are not adequate to meet the demand of

local communities.

Identification of manager’s contribution and benefits

• Imposed to use resources to the local communities

According to the office record of ShNP in the last fiscal year, more than 110 people were

punished due to illegal activities inside the park. It shows that there is pressure on the forest

resources from the surrounding communities. They are highly dependent upon the park

resources for their subsistence daily life and livelihoods.

Although there is 110 km loose stonewall to separate village with national park but it does not

function, crop damage, and livestock depredation are the common and serious problems. It is

creating conflict between park and local communities.

People are suffering from various aspects of the park management however, people are

contributing to conserve and manage the ShNP and park resources.

On average, crop damage costs are worth some NPR 2,873 a year for each park-dwelling

household. Loss of use of park resources due to restrictions on harvesting amounts to some

NPR 16,000 a year (comprising timber and NTFP use), and loss of access to agricultural

markets incurs average opportunity costs of NPR 8,000 per household per year.

• Management and conservation of resources and management cost

It was established as watershed area in 1976 and gazeeted as National Park in 2002. Ultimate

goal of this park is to conserve and manage the watershed area of Sundarijal which is the main

source of drinking water supply in Kathmandu valley. Total Nepalese Army staffs are 849 for

the protection purpose and annual budget including Rashan is NRs. 51.8 Millions (U$ 740,159)

and National Park has 60 staffs for the protection and management of park and park resources.

Annual budget is NRs. 11.0 Millions (U$157142). Altogether, there are 909 staffs and budget

is NRs. 62.8 million. All of these amounts of money directly go from the national treasure

• Benefits to the resource managers

Local communities are getting forest products from the park either legally or illegally. Water is

used for irrigation, drinking water, griddling machine, livestock pond and others households

uses.

People are getting benefits from the tourism enterprises. Altogether there are 25 hotels,

restaurants, lodges, teashops and other facilities and services in and around park. Some people

are getting employment opportunities from the tourism. Natural beauties and environmental

services are others benefits getting by local communities.

It reduced landslide and soil erosion of the catchment area and automatically it decreased

property loss and human casualties of local settlements. Another important benefit is it increased

land productivity of local farmers.

70 SUFFREC The Initiation 2008

Distribution

Benefit sharing mechanisms is not in the place. Institution set up is essential in the local level

either through local governance bodies or declaration of Buffer zone as soon as possible. To

participate local communities in decision making, planning process, implementation, monitoring

and evaluation is the most important.

Community forests are the vital to fulfill the basic needs of forest products of local communities.

It would also be the source of income generation and employment opportunities to support

their livelihoods.

Conclusion

PES is a new concept and burning issue in the recent days. It is pro-poor and equitable benefit

sharing mechanism. Moreover, PES enhances livelihoods, sustainable development, and

improvement of socio-economic condition.

There is lack of clear provision in policy, acts, rules, regulations, and guidelines to address the

issue of PES and benefit sharing. Appropriate environmental governance policy formulation

and institutional set up is required.

Managers are suffering and free riders are getting benefits so, appropriate benefit sharing

mechanism should be developed to resolve the problem of upstream and downstream conflict.

Awareness creation and empowerment of local communities is most essential to improve their

livelihoods and biodiversity conservation through PES mechanism.

Declaration of Buffer Zone (BZ) is the first step to take initiation for PES. After declaration of

BZ, at least 50 % amount of revenue directly goes to buffer zone communities. That money

will be used to improve their socio-economic condition of local communities and biodiversity

conservation of BZ.

Without any economic benefits local communities are suffering by livestock damage, crop

depredation by wild animals, imposed use of natural resources. Moreover, restriction on land

use options and huge amount of money has been invested government for the conservation

and management of ShNP. To compensate such contributions and sacrifices PES mechanism

is inevitable and the best.

Environmental benefits is also needed to be identified and valued properly to convince the

decision makers about importance of managing upper catchments as a part of water supply

infrastructure.

Acknowledgement

Mr. Puran Bhakta Shrestha, Chief Conservation Officer of ShNP provided access to recent

information and resources available in the park. Assistant Conservation Officer, Mr. Hari

Bhadra Acharya, Ranger Mr. Bishnu Prasad Pandey, Mr. Sarojmani Paudel, Office Assistant,

Mr. Keshav Parajuli, Mr. Basu Dev Chalise and other staffs of ShNP not only provided

information but also assisted in the field visit. I would like to extend gratitude to all of them.

The Initiation 2008 SUFFREC 71

References:

BPP 1995a. Biodiversity Profile of the Midhills of Nepal. BPP Publication no. 13. DNPWC,

Kathmandu.

CIFOR (2002) Making Forest Carbon Markets Work for Low-income Producers, CIFOR

Info-brief, Oct. 2003, No. 2. Indonesia.

Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2008. Payment for Environmental Services: an

emerging issue to be addressed. Banko Janakari 18(1):1

Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, 2006. Shivapuri National Park

FAO/HMG, 1996. Shivapuri Management Plan: Technical recommendations and policy design

for the protection and development fo the Shivapuri area including the participatory

management of Shivapuri Resources. Kathmandu: (GCP/NEP/048/NOR).

Karn, Prakash K. 2008. Making Payment for environmental services (PES) work: A case

study of Shivapuri National Park, Nepal. In Shifting Paradigms in Protected Area

Management (Ed) Bajracharya S. B., Dahal, N., NTNC, Nepal,171-185.

Khatri Chheri, J. B. 1993. A Study on Socio-economic in Shivapuri Watershed Area. SIWDP,

GCP/NEP/048/NOR, Field Document No. 3.

KMTNC, 2004. Shivapuri National Park Management Plan.

Maharjan, Maksha R. 2004. Payment for Environmental Services in Community Forestry. In

25 years of community forestry: Contributing to Millennium Development Goals,

proceedings of the fourth National workshop on community forestry (Ed) Kanel, K. et

al. Community Forest Division, Department of Forest, Nepal, 371-377.

MOEST, 2008. State of Environment, Brown sector (unpublished).

NARM 2004. Poverty Reduction through Sustainable Management of Protected Areas and

Wetlands in Nepal: Processes, modalities, Impacts and Identification of Areas for Future

Support, Volumes I and II. JICA, Kathmandu

Shivapuri National Park,2005. Wetlands of Shivapuri National Park.

Wunder, S. (2005). Payment for environmental services: Some nuts and bolts, Occasional

paper No. 42. Bogor: Centre for International Forestry Research.

http://www.csc.noaa.gov/text/direct. Environmental valuation: Principles, Techniques, and

Applications. NOAA Coastal Services Center 2234 South Hobson Avenue

Charleston, SC.

http://go.worldbank.org/51KUO12O50. Payements for Environnemental Services.

72 SUFFREC The Initiation 2008

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Demand in the Desert: Mongolia's Water-Energy-Mining NexusDe la EverandDemand in the Desert: Mongolia's Water-Energy-Mining NexusÎncă nu există evaluări

- REDD Consultations in Palawan - SangkulaDocument32 paginiREDD Consultations in Palawan - SangkulaValerie PacardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Payments for Ecological Services and Eco-Compensation: Practices and Innovations in the People's Republic of ChinaDe la EverandPayments for Ecological Services and Eco-Compensation: Practices and Innovations in the People's Republic of ChinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 318 160428 TII FactsheetsDocument34 pagini318 160428 TII FactsheetsJosh ChÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organisation-Institutions - Programmes: by Meine Van NoordwijkDocument4 paginiOrganisation-Institutions - Programmes: by Meine Van NoordwijkMunajat NursaputraÎncă nu există evaluări

- s10668 021 01826 XDocument25 paginis10668 021 01826 XRocio Idrogo BurgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- REDD+ and Forest Governance in NepalDocument8 paginiREDD+ and Forest Governance in NepalNepal_NatureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mitigation of Human – Elephant Conflict (HEC) through introduction of less vulnerable, innovative agricultural production systems – A pilot project in Laggala - Pallegama DS division, Central province of Sri Lanka.Document44 paginiMitigation of Human – Elephant Conflict (HEC) through introduction of less vulnerable, innovative agricultural production systems – A pilot project in Laggala - Pallegama DS division, Central province of Sri Lanka.sekanayake2260Încă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Ecosystem Services Value in A National Park PilotDocument14 paginiAssessment of Ecosystem Services Value in A National Park Pilotjacky cadulongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic Valuation of Riverside Wetland Services in The Lower Moshi Irrigation SchemeDocument20 paginiEconomic Valuation of Riverside Wetland Services in The Lower Moshi Irrigation SchemeInternational Journal of Innovative Research and Studies100% (1)

- Natural Resources, Livelihoods, and Reserve Management: A Case Study From Sundarbans Mangrove Forests, BangladeshDocument13 paginiNatural Resources, Livelihoods, and Reserve Management: A Case Study From Sundarbans Mangrove Forests, BangladeshVashabi GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessments of Ecosystem Service Indicators and Stakeholder'sDocument10 paginiAssessments of Ecosystem Service Indicators and Stakeholder'sKamal P. GairheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dave and MaheshDocument5 paginiDave and Maheshbentarigan77Încă nu există evaluări

- Paper Valoración Parques PDFDocument10 paginiPaper Valoración Parques PDFSantiago CuencaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S2212041621000164 Main 1Document24 pagini1 s2.0 S2212041621000164 Main 1DidiherChacon ChaverriÎncă nu există evaluări

- District Climate and Energy Plan IlamDocument169 paginiDistrict Climate and Energy Plan IlamSazzan NpnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic Value Assessment On The Ecosystem Services of Nansi Lake in ChinaDocument8 paginiEconomic Value Assessment On The Ecosystem Services of Nansi Lake in ChinaIOSRjournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vol XXIII No2 Dec 13Document127 paginiVol XXIII No2 Dec 13resultbdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Flows: State-of-the-Art With Special Reference To Rivers in The Ganga River BasiDocument33 paginiEnvironmental Flows: State-of-the-Art With Special Reference To Rivers in The Ganga River BasiriteshreplyÎncă nu există evaluări

- MPRA Paper 77068Document20 paginiMPRA Paper 77068Mahyudin MusthafaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towards An Innovative Approach To Integrated Wetland Management in Rupa Lake Area of NepalDocument6 paginiTowards An Innovative Approach To Integrated Wetland Management in Rupa Lake Area of NepalGandhiv KafleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prosiding 1Document9 paginiProsiding 1Wahyudi IsnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- KP Integrated Tourism Development Project PDFDocument12 paginiKP Integrated Tourism Development Project PDFhafeezjamaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manfaat Hidrologi Di Taman Nasional Bantimurung Bulusaraung, Sulawesi SelatanDocument25 paginiManfaat Hidrologi Di Taman Nasional Bantimurung Bulusaraung, Sulawesi SelatanId Adam MoehammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ecology Notes Natural ResourcesDocument23 paginiEcology Notes Natural ResourcesRaj AryanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic Values of Irrigation Water in Wondo Genet District, EthiopiaDocument15 paginiEconomic Values of Irrigation Water in Wondo Genet District, EthiopiaAlexander DeckerÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Estimation of Ecosystem Services ValDocument10 paginiThe Estimation of Ecosystem Services Val許閔筌Încă nu există evaluări

- HRMB Group 2 PPT LiteDocument24 paginiHRMB Group 2 PPT LiteSneha SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- C.note Hiwot-2Document5 paginiC.note Hiwot-2Yared Mesfin FikaduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conservation and Multiple Purpose Dam MaDocument17 paginiConservation and Multiple Purpose Dam MaBawa SheriffÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ilagan Watershed Reports 5tongsonDocument35 paginiIlagan Watershed Reports 5tongsonestherboerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainable Approach For Conserving andDocument15 paginiSustainable Approach For Conserving andNeel KinariwalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- TOPIC: Case Study On Eco-Tourism Spot in India (Kerala - Karnataka)Document9 paginiTOPIC: Case Study On Eco-Tourism Spot in India (Kerala - Karnataka)Melwin MejanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Govt. Initiatives To Tackle Env. Degradation-1Document14 paginiGovt. Initiatives To Tackle Env. Degradation-1RoHit SiNghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ini Ya RekDocument6 paginiIni Ya RekSyahputra WibowoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6353 22542 1 PBDocument14 pagini6353 22542 1 PBLemi TuroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case For SupportDocument3 paginiCase For SupportDhungana SuryamaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rewarding Farmers For Reducing Sedimentation, Indonesia: in A NutshellDocument3 paginiRewarding Farmers For Reducing Sedimentation, Indonesia: in A NutshellBjorn SckaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Socio-Economic Aspects of Cheleleka Wetland: Current Status and Future ProspectsDocument11 paginiSocio-Economic Aspects of Cheleleka Wetland: Current Status and Future Prospectshaymanotandualem2015Încă nu există evaluări

- OK Muñoz 2008 PDFDocument12 paginiOK Muñoz 2008 PDFMilena GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towards An Economic Approach To Sustainable Forest DevelopmentDocument36 paginiTowards An Economic Approach To Sustainable Forest DevelopmentRalph QuejadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Danao Madonna Finalreport PDFDocument80 paginiDanao Madonna Finalreport PDFkeeshan dhayneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ecotourism Product Prospecting at Kampung Kolosunan, Inanam, Sabah - For MergeDocument13 paginiEcotourism Product Prospecting at Kampung Kolosunan, Inanam, Sabah - For MergeSteward Giman StephenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ecotourism Product Prospecting at Kampung Kolosunan, Inanam, Sabah - For MergeDocument13 paginiEcotourism Product Prospecting at Kampung Kolosunan, Inanam, Sabah - For MergeSteward Giman StephenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who Benefits From Ecosystem Services? A Case Study For Central Kalimantan, IndonesiaDocument14 paginiWho Benefits From Ecosystem Services? A Case Study For Central Kalimantan, IndonesiaMohd. YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- PhysicDocument10 paginiPhysicSantosh Shah100% (1)

- The Role of Hydropower in Visions of Water Resources Development For Rivers of Western NepalDocument29 paginiThe Role of Hydropower in Visions of Water Resources Development For Rivers of Western NepalNeeraj BhattaraiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strem Shed Development ReportDocument15 paginiStrem Shed Development ReportRohitÎncă nu există evaluări

- (EMP) For Melamchi Water Supply Project, NepalDocument10 pagini(EMP) For Melamchi Water Supply Project, NepalAshish Mani LamichhaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strem Shed Development ReportDocument15 paginiStrem Shed Development ReportRohitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Govt. Initiatives To Tackle Env. DegradationDocument11 paginiGovt. Initiatives To Tackle Env. DegradationRoHit SiNghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decentralised Waste Water Management Constructed Wetlands NepalDocument12 paginiDecentralised Waste Water Management Constructed Wetlands NepalM. Aqeel SaleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ecosystem Services Quick GuideDocument8 paginiEcosystem Services Quick GuideCharlotte EdgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Pre-Proof: Environmental and Sustainability IndicatorsDocument35 paginiJournal Pre-Proof: Environmental and Sustainability IndicatorsSG GhoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paya Indah WetlandsDocument9 paginiPaya Indah Wetlandszulkis73Încă nu există evaluări

- Prakash Chandra Misra - Approved SynopsisDocument22 paginiPrakash Chandra Misra - Approved SynopsisAnujÎncă nu există evaluări

- Payment For Environmental Services On Batang Hari River JambiDocument11 paginiPayment For Environmental Services On Batang Hari River JambiWiwik WiwikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Distributional Inequality Between Community Forest User GroupDocument72 paginiDistributional Inequality Between Community Forest User GrouphariramharikrishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diesel and Electricity CostDocument22 paginiDiesel and Electricity CostMd.Zesanul KabirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biodiversity Protection Indonesia PDFDocument8 paginiBiodiversity Protection Indonesia PDFDjokwin WalkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brand Management Project-Royal Enfield: Sjmsom, Iit BombayDocument11 paginiBrand Management Project-Royal Enfield: Sjmsom, Iit BombaykabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annual Report 2073.74 Combined and Low Volume PDFDocument120 paginiAnnual Report 2073.74 Combined and Low Volume PDFkabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accounting Equation 1Document28 paginiAccounting Equation 1kabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Comparative Study On Investment Policy of Nabil and Nepal Sbi Bank Ltd.Document111 paginiA Comparative Study On Investment Policy of Nabil and Nepal Sbi Bank Ltd.kabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 6 Financial Estimates and ProjectionsDocument19 paginiChapter 6 Financial Estimates and ProjectionskabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medicine BoxDocument19 paginiMedicine Boxkabibhandari100% (1)

- Intellectual Property Rights MBA BDocument9 paginiIntellectual Property Rights MBA BkabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- FastfoodDocument98 paginiFastfoodkabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tata Motors AR 2012-13 PDFDocument208 paginiTata Motors AR 2012-13 PDFkabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3: Overcoming Communication BarriersDocument22 paginiModule 3: Overcoming Communication BarrierskabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communication BarriersDocument41 paginiCommunication Barrierskabibhandari100% (1)

- Managing Diversity in The WorkplaceDocument10 paginiManaging Diversity in The WorkplacekabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Proposal Writing: Title Cover Page Chapter I: IntorductionDocument1 paginăProject Proposal Writing: Title Cover Page Chapter I: IntorductionkabibhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

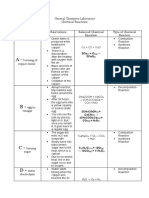

- General Chemistry Laboratory Chemical Reactions Results: Reaction Observations Balanced Chemical Equation Type of Chemical ReactionDocument2 paginiGeneral Chemistry Laboratory Chemical Reactions Results: Reaction Observations Balanced Chemical Equation Type of Chemical ReactionArianeÎncă nu există evaluări

- QGL-CE-001Guidelines For Corridors and Corridor CrossingsRev2Document29 paginiQGL-CE-001Guidelines For Corridors and Corridor CrossingsRev2tomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appendix Sizing The Building Water Supply and Distribution Piping SystemsDocument36 paginiAppendix Sizing The Building Water Supply and Distribution Piping SystemsMahmood BadawiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fosroc Conbextra GP TDSDocument4 paginiFosroc Conbextra GP TDSKAVINÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of ShampoosDocument3 paginiEvaluation of ShampoosprinceamitÎncă nu există evaluări

- In-Class Thermochemistry Practice Problems Name - Ella Bomberger - Date - Block - BDocument3 paginiIn-Class Thermochemistry Practice Problems Name - Ella Bomberger - Date - Block - BElla BombergerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Armfield Ht31 Tubular Heat Exchanger in The Education KeywordsDocument3 paginiArmfield Ht31 Tubular Heat Exchanger in The Education KeywordsCHERUYIOT IAN100% (1)

- Condition Monitoring: Product CatalogueDocument100 paginiCondition Monitoring: Product Catalogueboodi_eidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Air and Water Pollution in Mthatha: Physical SciencesDocument15 paginiAir and Water Pollution in Mthatha: Physical SciencesLilitha Lilly MfoboÎncă nu există evaluări

- MTWD HistoryDocument8 paginiMTWD HistoryVernie SaluconÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surface & Coatings Technology: Alberto Ceria, Peter J. HauserDocument7 paginiSurface & Coatings Technology: Alberto Ceria, Peter J. HauserSamuel MartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary Extra ExerciseDocument2 paginiSummary Extra Exercisechunkit033Încă nu există evaluări

- Rainwater Harvesting 101 - Your How-To Collect Rainwater GuideDocument13 paginiRainwater Harvesting 101 - Your How-To Collect Rainwater GuideNitheesh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accumulation On and Extraction of Lead From Point-Of-Use Filters For Evaluating Lead Exposure From Drinking WaterDocument26 paginiAccumulation On and Extraction of Lead From Point-Of-Use Filters For Evaluating Lead Exposure From Drinking WaterNermeen ElmelegaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Datos para El Modelo.: Determinantes UnidadesDocument8 paginiDatos para El Modelo.: Determinantes UnidadesVaNe Arzayus TrujilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modelling of Chloride PenetrationDocument26 paginiModelling of Chloride PenetrationDamir ZenunovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- IWA City Stories SingaporeDocument2 paginiIWA City Stories SingaporeThang LongÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study On Water Quality of Aami River in GorakhpurDocument6 paginiA Study On Water Quality of Aami River in GorakhpurGJESRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conceptual Plan: M/s. Indore Municipal CorporationDocument33 paginiConceptual Plan: M/s. Indore Municipal Corporationhrithik agnihotriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced Hydraulic Structure Presentation On: Spillway ConstructionDocument24 paginiAdvanced Hydraulic Structure Presentation On: Spillway ConstructionEyasu TafeseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aula Lucis Thomas Vaughan: To Seleucus AbantiadesDocument12 paginiAula Lucis Thomas Vaughan: To Seleucus AbantiadesBucin MirceaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 00029487Document12 pagini00029487Régis OngolloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self - Priming Centrifugal Pumps: MotorDocument2 paginiSelf - Priming Centrifugal Pumps: MotorbheemsinghsainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHEM 181: An Introduction To Environmental ChemistryDocument21 paginiCHEM 181: An Introduction To Environmental ChemistrymArv131994Încă nu există evaluări

- Emalex 602: Safety Data SheetDocument6 paginiEmalex 602: Safety Data SheetShahbaz QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- VACUKLAV-31B+ ManualDocument58 paginiVACUKLAV-31B+ ManualpagulahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab Report Specific HeatDocument5 paginiLab Report Specific HeatAhmad Shahir ShakriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study of Parameters Affecting Dry and Wet Ozone Bleaching of Denim FabricDocument8 paginiStudy of Parameters Affecting Dry and Wet Ozone Bleaching of Denim FabricMd.HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wall Wash Test: 1. PreparationDocument4 paginiWall Wash Test: 1. PreparationJeet Singh100% (2)

- The War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionDe la EverandThe War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (2)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldDe la EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (1146)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe la EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (32)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.De la EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (110)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndDe la EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndÎncă nu există evaluări

- When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfDe la EverandWhen Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (36)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedDe la Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (111)

- Our Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownDe la EverandOur Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (86)

- His Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsDe la EverandHis Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (100)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansDe la EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (19)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDe la EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (6)

- The Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelDe la EverandThe Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (21)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryDe la EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (46)

- The Other Significant Others: Reimagining Life with Friendship at the CenterDe la EverandThe Other Significant Others: Reimagining Life with Friendship at the CenterEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassDe la EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (27)

- The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchDe la EverandThe Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (13)

- The Perfection Trap: Embracing the Power of Good EnoughDe la EverandThe Perfection Trap: Embracing the Power of Good EnoughEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (25)

- The Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveDe la EverandThe Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (367)

- The Pursuit of Happyness: The Life Story That Inspired the Major Motion PictureDe la EverandThe Pursuit of Happyness: The Life Story That Inspired the Major Motion PictureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dark Feminine Energy: The Ultimate Guide To Become a Femme Fatale, Unveil Your Shadow, Decrypt Male Psychology, Enhance Attraction With Magnetic Body Language and Master the Art of SeductionDe la EverandDark Feminine Energy: The Ultimate Guide To Become a Femme Fatale, Unveil Your Shadow, Decrypt Male Psychology, Enhance Attraction With Magnetic Body Language and Master the Art of SeductionEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansDe la EverandAmerican Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (66)

- Confessions of a Funeral Director: How Death Saved My LifeDe la EverandConfessions of a Funeral Director: How Death Saved My LifeEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (10)