Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Predicting bacterial conjunctivitis

Încărcat de

Theodore LiwonganDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Predicting bacterial conjunctivitis

Încărcat de

Theodore LiwonganDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cite this article as: BMJ, doi:10.1136/bmj.38128.631319.

AE (published 16 June 2004)

Primary care

Predicting bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis: cohort study

on informativeness of combinations of signs and symptoms

Remco P Rietveld, Gerben ter Riet, Patrick J E Bindels, Jacobus H Sloos, Henk C P M van Weert

Abstract for these antibiotics are issued each year, at a cost to the NHS of

£4.7 million (€7.1 million, $8.7 million).10 11

Objective To find an efficient set of diagnostic indicators that To select those patients who might benefit most from antibi-

are optimally informative in the diagnosis of a bacterial origin otic treatment, the general practitioner needs an informative

of acute infectious conjunctivitis. diagnostic tool to determine a bacterial cause. With such a tool,

Design Cohort study involving consecutive patients. Results of antibiotic prescriptions may be reduced and better targeted.

index tests and reference standard were collected Most general practitioners make the distinction between a bacte-

independently from each other. rial cause and another cause on the basis of signs and symptoms.

Setting 25 Dutch health centres. Additional diagnostic investigations, such as a culture of the con-

Participants 184 adults presenting with a red eye and either junctiva, are seldom done, mostly because of the resulting

(muco)purulent discharge or glued eyelid(s), not wearing diagnostic delay. Can general practitioners actually differentiate

contact lenses. between bacterial and viral conjunctivitis on the basis of signs

Main outcome measures Probability of a positive bacterial and symptoms alone? Major textbooks list several signs and

culture, given different combinations of index test results; area symptoms that are supposed to be diagnostic for the cause of

under receiver operating characteristics curve. acute infectious conjunctivitis.12–14 A recently published system-

Results Logistic regression analysis showed optimal diagnostic atic literature search summed up the signs and symptoms and

discrimination for the combination of early morning glued found no evidence for these assertions.15 This paper presents

eye(s), itch, and a history of conjunctivitis. The first of these what seems to be the first empirical study on the diagnostic

indicators increased the likelihood of a bacterial cause, whereas informativeness of signs and symptoms in acute infectious con-

the other two decreased it. The area under the receiver junctivitis.

operating characteristics curve for this combination of

symptoms was 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.63 to 0.80). The

overall prevalence of bacterial involvement of 32% could be Methods

lowered to 4% or raised to 77%, depending on the pattern of Participants

index test results. We asked nine designated general practitioners, working in 25

Conclusion A bacterial origin of complaints indicative of acute care centres with a total of 41 general practitioners, in the

infectious conjunctivitis can be made much more likely or Amsterdam and Alkmaar region to include patients with a red

unlikely by the answers to three simple questions posed during eye and either (muco)purulent discharge or sticking of the

clinical history taking (possibly by telephone). These results may eyelids. The exclusion criteria were age younger than 18 years,

have consequences for more targeted prescription of ocular pre-existing symptoms for longer than seven days, acute loss of

antibiotics. vision, wearing of contact lenses, use of systemic or local antibi-

otics within the previous two weeks, ciliary redness, eye trauma,

and a history of eye surgery. All eligible patients were referred to

Introduction

one of the nine designated general practitioners for enrolment

In the developed world, acute infectious conjunctivitis is a com- in the study. Patients were recruited during office hours only.

mon disorder with an annual incidence of 1.5-2% in primary Participants gave written informed consent. We collected the

care.1–5 Randomised trials in patients with suspected acute bacte- data for this diagnostic study as part of the baseline

rial conjunctivitis show a pooled prevalence of bacterial measurements for a randomised trial on the treatment of acute

pathogens of 50% (95% confidence interval 45% to 54%).6–9 No infectious conjunctivitis. We used the complete cohort for this

more than half of the cases of acute infectious conjunctivitis in analysis.

primary care probably have a bacterial origin. Confronted with

acute infectious conjunctivitis, most general practitioners feel Data collection

unable to discriminate between a bacterial and a viral cause. In At inclusion of each participant, general practitioners completed

practice, more than 80% of such patients receive antibiotics.1 5 a standardised questionnaire and physical examination (index

Hence, in cases of acute infectious conjunctivitis, many unneces- tests). The questionnaire contained questions about medical his-

sary ocular antibiotics are prescribed. In 2001 in the tory (self reported), duration of symptoms (days), self medication

Netherlands, more than 900 000 prescriptions for topical ocular and self treatment, itching, burning sensation, foreign body sen-

antibiotics were issued, at a cost of €8.85 million (£5.9 million, sation, and the number of glued eyes in the morning (0, 1, or 2).

$10.9 million). In England 3.4 million community prescriptions The physical examination included investigation of the degree of

BMJ Online First bmj.com page 1 of 5

Primary care

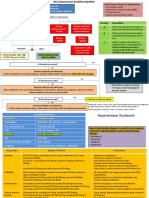

Eligible patients (n=184)

Refused to

paticipate (n=2)

Index tests (signs and symptoms)

and reference standard (culture) (n=182)

Bacterial Non-bacterial Results of culture

conjunctivitis (n=58) conjunctivitis (n=122) unknown (n=2)

Index test Index test

incomplete incomplete

(n=1) (n=2)

Analysed (n=57) Analysed (n=120)

Flow of participants through the study

redness (peripheral, whole conjunctiva, or whole conjunctiva and < 0.15 to be independent indicators of the presence of bacteria

pericorneal), the presence of periorbital oedema, the kind of dis- and retained them in the final model. We modelled determinants

charge (watery, mucous, or purulent), and bilateral involvement with more than two categories as dummy variables.17 We assessed

(yes or no). The general practitioner then took one conjunctival all second order interactions between the variables entered into

sample of each eye for a bacterial culture (reference standard). the final model. We deemed interaction to be present if the P

The general practitioners did not receive the culture results, and value associated with an interaction term was < 0.05.

the microbiologist who analysed the cultures had no knowledge We quantified the ability of the final model to discriminate

of the results of the index tests. between patients with and without a positive bacterial culture by

For each patient one eye was designated as the “study eye.” In using the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve

the case of two diseased eyes, the diseased eye with worse signs or with 95% confidence intervals.18 We quantified the reliability or

symptoms was the study eye. In the case of two equally affected calibration of the model by using the Hosmer-Lemeshow good-

eyes, the first affected eye was the study eye. ness of fit test. Finally, we bootstrapped the receiver operating

characteristics curve a thousand times to counteract potential

Microbiological procedures

undue influence of atypical patients on the predictions of the

General practitioners took one sample of the conjunctiva of each

final model.18

eye by rolling a cotton swab (Laboratory Service Provider,

We used the final model to estimate the probability of a posi-

Velzen-Noord, Netherlands) over the conjunctiva of the lower

tive bacterial culture for each individual patient given his or her

fornix. They put the swabs into transport medium and sent them

combination of test results. For each test result we generated a

to the investigating laboratory in Alkmaar. Directly after arrival,

clinical score by using the rounded regression coefficients asso-

we inoculated the swabs on to blood agar enriched with 5%

ciated with these test results. All possible combinations of test

sheep blood, MacConkey agar, and chocolate agar. All media

results led to different clinical scores, which could be used for

were made at the laboratory with standard ingredients (Becton

treatment decisions depending on the choice of a treatment cut-

Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD, USA). After standard inoculation,

off point. In this way, we could calculate the numbers of correctly

we incubated the blood agar and MacConkey agar plates for 48

treated patients (sensitivity of the chosen cut-off point) and cor-

hours at 35°C; we incubated the chocolate agar plates for the

rectly untreated patients (specificity) and the reduction in

same period and at the same temperature, but in a 7% CO2

prescriptions with different treatment cut-off points. We

atmosphere. We analysed cultures daily according to the

illustrated this by use of an example.

guidelines of the American Society for Microbiology.16 We iden-

We used SPSS (version 11.5.2) to do the statistical analyses.

tified all pathogens by using routine standard biochemical

We used Stata (version 7) to calculate the 95% confidence inter-

procedures. Colonies suspected to be pathogens were selected

vals around the predicted probabilities and to do the bootstrap-

and investigated by Gram stain. Depending on the results of the

ping.

Gram stain, we did additional tests. In the case of Gram positive

cocci, we did a catalase test followed by, for example, a coagulase

test (staphylococci) or an optochine (pneumococci) test. In the

case of Gram negative rods or cocci, we did sugar tests. Results

Statistical analysis Between September 1999 and December 2002 we enrolled 184

We assessed the associations between findings from the index patients; data from 177 (96%) of these could be analysed (fig).

tests and the presence of a positive bacterial culture in the study The reasons for non-inclusion were refusal (n = 2) or

eye by using a stepwise forward logistic regression analysis.17 The incompleteness of data (n = 5). Three patients had incomplete

dependent variable was the presence or absence of a bacterium. index tests, and the culture results for two patients were

We entered variables with a univariate P value of ≤ 0.10 into the unknown because the culture samples never arrived at the labo-

model. We considered variables with a multivariate P value of ratory.

page 2 of 5 BMJ Online First bmj.com

Primary care

Table 1 Baseline demographic characteristics and index test results and Table 3 Results of logistic regression analysis. Independent indicators of

their univariate odds ratios. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated positive bacterial culture and their clinical score

otherwise. The prevalence of a positive culture was 32% (57/177) Regression

Culture Indicator Odds ratio (95% CI) coefficient Clinical score*

Culture positive negative Two glued eyes 14.99 (4.36 to 51.53) 2.707 5

Characteristic (n=57) (n=120) Odds ratio (95% CI) One glued eye 2.96 (1.03 to 8.51) 1.086 2

Mean (SD) age (years) 47 (17) 42 (14) – Itching 0.54 (0.26 to 1.12) −0.61 −1

Median (range) duration of 2 (1-7) 3 (1-7) – History of conjunctivitis 0.31 (0.10 to 0.96) −1.161 −2

symptoms (days)

Area under ROC curve 0.74 (0.65 to 0.82) – –

Female 36 (63) 68 (57) – (95% CI)

History of hay fever 9 (16) 18 (15) 1.06 (0.45 to 2.54)

ROC=receiver operating characteristics.

History of conjunctivitis 5 (9) 25 (21) 0.37 (0.13 to 1.01) *Clinical scores of every symptom present are added up. For example, a patient with two

History of allergic 3 (5) 6 (5) 1.06 (0.25 to 4.38) glued eyes, itch, and no history of conjunctivitis has a clinical score of: 5 + −1 = 4.

conjunctivitis

Self treatment* 45 (79) 85 (71) 1.54 (0.73 to 3.26)

Redness: patients (corrected 95% confidence interval of area under curve

Peripheral 16 (28) 50 (42) 1 0.63 to 0.80).

Whole conjunctiva 29 (51) 50 (42) 1.81 (0.88 to 3.74) The logistic regression analysis generated 12 different

Conjunctival and 12 (21) 20 (17) 1.88 (0.75 to 4.66)

combinations of test results. These combinations corresponded

pericorneal

Periorbital oedema 20 (35) 41 (34) 1.04 (0.54 to 2.02)

to nine different clinical scores, varying from +5 to − 3. For each

Secretion: clinical score, we calculated the probability of a positive culture.

None or water 20 (35) 47 (39) 1 For a patient with a clinical score of +5, this probability was

Mucus 26 (46) 43 (36) 1.42 (0.70 to 2.90) increased from 32% (prevalence in this study) to 77% (table 4).

Purulent 11 (19) 30 (25) 0.86 (0.36 to 2.05) By contrast, a clinical score of − 3 lowered this probability to 4%.

Bilateral involvement 21 (37) 19 (16) 3.10 (1.50 to 6.42) Table 4 allows the calculation of the numbers of correctly treated

Itching 33 (58) 76 (63) 0.80 (0.42 to 1.52) patients (sensitivity) and correctly untreated patients (specificity)

Foreign body sensation 23 (40) 48 (40) 1.02 (0.53 to 1.93) and the reduction of prescriptions with different treatment

Burning sensation 37 (65) 69 (58) 1.37 (0.71 to 2.63) cut-off points. For example, if the treatment cut-off point is set at

Glued eyes: +2, indicating that only patients with a clinical score of +2 or

None 5 (8) 33 (27) 1

higher receive ocular antibiotics, 38/57 (67%) of patients are

One in the morning 30 (53) 74 (62) 2.68 (0.95 to 7.51)

correctly treated and 87/120 (73%) patients are correctly

Two in the morning 22 (39) 13 (11) 11.17 (3.49 to 35.77)

untreated. If applied to our study population, the cut-off point of

*Cleaning with water.

+2 would lead to a reduction in prescriptions of antibiotics from

more than 80% (current practice) to 40% (71/177).

The prevalence of a positive bacterial culture in the study eye

was 32% (57/177). The groups (culture positive and culture

negative) were comparable with respect to baseline demograph- Discussion

ics, but some notable differences existed in the results of index

This study seems to be the first empirical study on the informa-

tests (table 1). A history of conjunctivitis occurred more often in

tiveness of combinations of signs and symptoms to estimate the

participants with a negative culture (21% v 9%). In the group

probability of a positive bacterial culture in adult patients who

with a positive culture, more patients had two glued eyes in the

present to their general practitioner with a red eye and either

morning (39% v 11%) and bilateral involvement (37% v 16%).

(muco)purulent discharge or glued eyes. In contrast to what is

The most prevalent species was Streptococcus pneumoniae, which

stated in most textbooks, for example, purulent secretion seems

accounted for 27/57 of the positive cultures (table 2).

to be diagnostically almost non-informative.12–14 However, the

Three determinants were retained in the multivariable

combination of three diagnostic indicators—glued eyes, itch, and

regression analysis: history of conjunctivitis (yes or no), itch (yes

a history of conjunctivitis—provided optimal discrimination

or no), and glued eyes in the morning (0, 1, or 2). Table 3 lists the

between patients with and without a positive culture. It is of prac-

odds ratios of these independent indicators of a positive bacterial

tical interest that these indicators may all be collected by clinical

culture and their clinical scores. We found no statistical

history taking or by telephone interview.

interactions.

A history of infectious conjunctivitis and itch both made the

The area under the receiver operating characteristics curve

probability of current bacterial involvement less likely. This may

of the final model was 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.65 to

be explained by assuming that a viral conjunctivitis is more

0.82). The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test had a P value

prevalent or has a stronger tendency to recur than a bacterial

of 0.117, indicating that the model does not misrepresent the

conjunctivitis and that itch indicates an allergic cause.

data.17 Validation of this model with the bootstrap technique

The use of the logistic regression model allows for the

showed hardly any indication of undue influence by particular

flexible creation of easy to use clinical rules. However, as long as

more formal decision analyses do not exist, the choice of a

Table 2 Culture results rational treatment threshold remains somewhat arbitrary. We

Pathogen No (%) (n=57) used the example of a treatment cut-off point of +2 to illustrate

Streptococcus pneumoniae 27 (47) an approximate reduction of antibiotic prescriptions from more

Staphylococcus aureus 13 (23) than 80% to 40%. These data indicate that in the absence of

Haemophilus influenzae 9 (16) “alarm symptoms” the decision whether to prescribe antibiotics

Coagulase negative staphylococci 5 (9) could be made without any additional diagnostic tests. This could

Streptococcus haemolyticus, group C 1 (2) lead to a substantial reduction in the costs associated with

Other bacteria 2 (4) prescription of topical antibiotics. Use of a treatment cut-off

BMJ Online First bmj.com page 3 of 5

Primary care

Table 4 Clinical scores and their associated probabilities of a positive culture, sensitivity, and specificity

Percentage (No) observed positive Percentage (95% CI) predicted positive Percentage correctly treated Percentage correctly untreated

Clinical score cultures* cultures† (sensitivity)‡ (specificity)§

+5 100 (5/5) 77 (57 to 90) 9 100

+4 71 (17/24) 65 (47 to 79) 39 94

+3 0 (0/3) 51 (23 to 79) 39 92

+2¶ 41 (16/39) 40 (26 to 55) 67 73

+1 20 (10/51) 27 (17 to 39) 84 38

0 13 (3/23) 18 (7 to 38) 89 22

−1 20 (5/25) 11 (4 to 26) 98 5

−2 0 (0/1) 7 (2 to 28) 98 4

−3 17 (1/6) 4 (1 to 15) 100 0

*Overall prevalence of positive culture=32% (57/177). In parenthesis are the number of positive cultures (numerator) and total number of cultures (denominator) in that row.

†Predicted probability is the probability of a positive culture calculated by regression analysis.

‡Fraction of patients with a positive culture who would be correctly treated if the clinical score in that row was used as treatment cut-off point.

§Fraction of all patients with a negative culture who would be correctly untreated if the clinical score in that row was used as treatment cut-off point.

¶Clinical score of +2 used in the text to illustrate its use for treatment decisions.

point means that some patients with a positive culture will not Contributors: HCPMvanW had the original idea. HCPMvanW and PJEB

receive treatment. The question is whether this is acceptable. A wrote the protocol and gained funding. RPR collected the data. RPR and

GterR analysed the data. JHS analysed the bacterial cultures. RPR wrote the

meta-analysis indicated that suspected acute bacterial conjuncti- first draft of the paper, which was edited by all other authors. HCPMvanW

vitis is mostly a self limiting disorder, with no serious is the guarantor for the study.

complications in the placebo arms of the included studies. How- Funding: Dutch College of General Practitioners, Utrecht.

ever, this meta-analysis also showed that treatment with Competing interests: None declared.

antibiotic was associated with significantly better rates of early Ethical approval: The medical ethics committee of the Academic Medical

(days 2 to 5) clinical remission (relative risk 1.3, 95% confidence Center, Amsterdam, approved the original trial protocol.

interval 1.1 to 1.6).4

Doctors who feel inclined to use these results in their daily 1 Okkes IM, Oskam SK, Lamberts H. Van klacht naar diagnose: episodegegevens uit de

huisartspraktijk. Bussum: Coutinho, 1998.

practice should be aware of several factors. Firstly, the clinical 2 Van der Werf GT, Smit RJA, Stewart RE, Meyboom de Jong B. Spiegel op de huisarts: over

domain to which our results apply does, of course, not formally registratie van ziekte, medicatie en verwijzing in de geautomatiseerde huisartspraktijk. Gronin-

gen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, 1998.

include patient types that were excluded—for example, patients 3 Van de Lisdonk EH, Bakx J. Continue morbiditeits registratie: ziekten in de huisartspraktijk.

with acute loss of vision and contact lens wearers. Secondly, as we Bunge: Elsevier, 1999.

4 Sheikh A, Hurwitz B. Topical antibiotics for acute bacterial conjunctivitis: a systematic

instructed the general practitioners especially for the study, the review. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51:473-7.

results may not be fully replicated if used by general practitioners 5 Everitt H, Little P. How do GPs diagnose and manage acute infective conjunctivitis? A

GP survey. Fam Pract 2002;19:658-60.

not similarly instructed. Thirdly, an independent replication of 6 Horven I. Acute conjunctivitis: a comparison of fusidic acid viscous eye drops and

our study would be useful, as other diagnostic indicators may chloramphenicol. Acta Ophthalmol 1993;71:165-8.

perform better in other populations or the same indicators may 7 Miller IM, Wittreich J, Vogel R, Cook TJ. The safety and efficacy of topical norfloxacin

compared with placebo in the treatment of acute, bacterial conjunctivitis. Eur J

be associated with different degrees of informativeness.18 On the Ophthalmol 1992;2:58-66.

other hand, we took some precautions against overoptimism in 8 Gallenga PE, Lobefalo L, Colangelo L, Della Loggia G, Orzalesi N, Velati P, et al. Topi-

cal lomefloxacin 0.3% twice daily versus tobramycin 0.3% in acute bacterial conjuncti-

regression analysis by limiting the number of variables to four, vitis: a multicenter double-blind phase III study. Ophthalmologica 1999;213:250-7.

which is below the rule of thumb stating that this number should 9 Agius-Fenandez A, Patterson A, Fsadni M, Jauch A, Raj PS. Topical lomefloxacin versus

topical chloramphenicol in the treatment of acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Clin Drug

be no bigger than the number of cases of the target disease Invest 1998;15:263-9.

divided by 10.18 As we had 57 cases, the use of four variables 10 Genees en hulpmiddelen Informatie Project. Annual report prescription data. College

voor zorgverzekeringen, Amstelveen, 2001.

complies with that rule. In addition, the bootstrap procedure

should be a safeguard against finding a regression model that is

influenced too much by particular patients that are not found What is already known on this topic

outside our dataset. No evidence has been published to show that clinical signs,

This study was limited to adult patients. The incidence of symptoms, or both help to distinguish bacterial from viral

acute infectious conjunctivitis in children is higher than in adults, conjunctivitis

and the spectrum of causative micro-organisms may differ from

that in adults. Therefore, these results cannot automatically be General practitioners would benefit from an easy to use

applied in children. diagnostic tool to make this distinction

The low prevalence of a positive bacterial culture found in

this study indicates that general practitioners unnecessarily pre- What this study adds

scribe topical ocular antibiotics in most cases of acute infectious General practitioners can increase or reduce the chances

conjunctivitis.1 5 This prescription policy may increase the risk of that conjunctivitis is bacterial by asking about the number

antibiotic resistance,19–21 and the number of patients who experi- of glued eyes, itch, and history of infectious conjunctivitis

ence side effects, and is responsible for relatively high costs asso-

ciated with prescription of these drugs.10 11 We hope that our General practitioners could use this diagnostic information

approach will stimulate others to replicate our findings, in their decisions about antibiotic treatment

including studies in children. Eventually this may lead to the

construction of a reliable and easy to use tool to restrict the pre- A considerable reduction in the number of prescriptions for

scription of antibiotics in patients presenting with a red eye and topical ocular antibiotics could be achieved, while avoiding

conjunctival discharge to those with a suitably high probability of harm or much discomfort

an underlying bacterial cause.

page 4 of 5 BMJ Online First bmj.com

Primary care

11 Department of Health. Prescription cost analysis data. Leeds: Department of Health, 21 Goldstein MH, Kowalski RP, Gordon YJ. Emerging fluoroquinolone resistance in bac-

1998. terial keratitis: a 5-year review. Ophthalmology 1999;106:1313-8.

12 Krachmer JH. Cornea. St Louis: Mosby, 1997.

13 Kanski JJ. Clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, (Accepted 13 May 2004)

1999.

14 Tasman W, Jaeger EA. Duane’s clinical ophthalmology on CD-Rom. Lippincot Williams doi 10.1136/bmj.38128.631319.AE

and Wilkins, 2001.

15 Rietveld RP, Van Weert HC, Riet ter G, Bindels PJ. Diagnostic impact of signs and

symptoms in acute infectious conjunctivitis: systematic literature search. BMJ Division of Clinical Methods and Public Health, Department of General Practice,

2003;327:789. Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ,

16 Hall GS, Pezzlo M. Ocular cultures. In: Isenberg HD, ed. Clinical microbiology procedures Amsterdam, Netherlands

handbook. Washington: American Society for Microbiology, 1995.

Remco P Rietveld general practitioner

17 Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons,

1989. Patrick J E Bindels professor in general practice

18 Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing Henk C P M van Weert general practitioner

models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Horten-Zentrum, Zurich, Switzerland

Stat Med 1996;15:361-87.

Gerben ter Riet epidemiologist

19 Brown EM, Thomas P. Fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Lancet

2002;359:803. Medical Centre Alkmaar, Alkmaar, Netherlands

20 Mills O Jr, Thornsberry C, Cardin CW, Smiles KA, Leyden JJ. Bacterial resistance and Jacobus H Sloos consultant microbiologist

therapeutic outcome following three months of topical acne therapy with 2% erythro-

Correspondence to: R P Rietveld r.p.rietveld@amc.uva.nl

mycin gel versus its vehicle. Acta Derm Venereol 2002;82:260-5.

BMJ Online First bmj.com page 5 of 5

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Nursing Care Plans For Delusional DisorderDocument4 paginiNursing Care Plans For Delusional Disorderkirill61195% (22)

- Worksheet Chapter 6Document42 paginiWorksheet Chapter 6kevin fajardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adiuvo Publications - 2022 UpdatedDocument42 paginiAdiuvo Publications - 2022 Updatedrahul krishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ultrasound Findings in FIP CatsDocument73 paginiUltrasound Findings in FIP Catsludiegues752Încă nu există evaluări

- Practice Quiz For EpidemiologyDocument4 paginiPractice Quiz For EpidemiologyOsama Alhumisi100% (3)

- Comparative Study On The Efficacy of Non-Steroidal, Steroid and Non-Use Anti Inflammatory in The Treatment of Epidemic ConjungtivitisDocument6 paginiComparative Study On The Efficacy of Non-Steroidal, Steroid and Non-Use Anti Inflammatory in The Treatment of Epidemic ConjungtivitisVisakha VidyadeviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal EED 3Document10 paginiJurnal EED 3Garsa GarnolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bacterial KeratitisDocument6 paginiBacterial KeratitisMelia RahmayantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Keratitis Por Adenovirus 2018Document8 paginiKeratitis Por Adenovirus 2018pachisfmbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eclinicalmedicine: Research PaperDocument8 paginiEclinicalmedicine: Research PaperEl LitoralÎncă nu există evaluări

- CDC Repeat Syphilis Infection and HIV Coinfection Among Men Who Have SexDocument16 paginiCDC Repeat Syphilis Infection and HIV Coinfection Among Men Who Have SexkikiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bacterial Keratitis Risk Factors and Microbiology ReviewDocument5 paginiBacterial Keratitis Risk Factors and Microbiology Reviewlathifa_nurÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Immunopharmacology: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument9 paginiInternational Immunopharmacology: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsPujiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treating adenoviral conjunctivitis with povidone-iodine and dexamethasoneDocument7 paginiTreating adenoviral conjunctivitis with povidone-iodine and dexamethasoneKurnia22Încă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Nirza MataDocument15 paginiJurnal Nirza MataRozans IdharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use of Indicators For Good Infection Control PracticeDocument2 paginiUse of Indicators For Good Infection Control PracticeZY YanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2021 Nac EscmiDocument10 pagini2021 Nac EscmiJesus PlanellesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal - Bilateral Simultaneous Infective KeratitisDocument4 paginiJournal - Bilateral Simultaneous Infective KeratitisAndayanaIdhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Study: Outcome and Prognostic Factors For Traumatic Endophthalmitis Over A 5-Year PeriodDocument8 paginiClinical Study: Outcome and Prognostic Factors For Traumatic Endophthalmitis Over A 5-Year PeriodannisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treating Pediatric Conjunctivitis Without An Exam: An Evaluation of Outcomes and Antibiotic UsageDocument6 paginiTreating Pediatric Conjunctivitis Without An Exam: An Evaluation of Outcomes and Antibiotic UsageTika Renwarin Tua ElÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eclinicalmedicine: Research PaperDocument9 paginiEclinicalmedicine: Research PaperStephanie Perales MuñozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dry Eye in Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis: A Cross-Sectional Comparative StudyDocument4 paginiDry Eye in Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Studyamandashn96Încă nu există evaluări

- AygunDocument5 paginiAygunotheasÎncă nu există evaluări

- HiTEMP TrialDocument8 paginiHiTEMP TrialJorge BarriosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1198743X18308565 MainDocument6 pagini1 s2.0 S1198743X18308565 MainYulia Niswatul FauziyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary of The Evidence For Ivermectin in COVID-19Document3 paginiSummary of The Evidence For Ivermectin in COVID-19Kent CheeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The New Zealand Medical JournalDocument7 paginiThe New Zealand Medical JournalNafhyraJunetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research ArticleDocument6 paginiResearch ArticleReffy AdhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Antigen Tests and Results ENG FinalDocument4 paginiUnderstanding Antigen Tests and Results ENG FinalAna CatarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 Article 294 PDFDocument7 pagini2016 Article 294 PDFChato Haviz DanayomiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bak TeriDocument4 paginiBak TeriHawania IIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ocular Outcomes After Treatment of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis Using Adoptive Immunotherapy With CMV Specific Cytotoxic T LymphocytesDocument39 paginiOcular Outcomes After Treatment of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis Using Adoptive Immunotherapy With CMV Specific Cytotoxic T LymphocytesmorelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ocular Findings and Proportion With Conjunctival SARS-COV-2 in COVID-19 PatientsDocument2 paginiOcular Findings and Proportion With Conjunctival SARS-COV-2 in COVID-19 PatientsYekiita QuinteroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Article Current Evidence of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Ocular Transmission: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument8 paginiReview Article Current Evidence of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Ocular Transmission: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysisoktaviano okkiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Umbilical Cord Serum Therapy in Acute Ocular Chemical BurnsDocument6 paginiEvaluation of Umbilical Cord Serum Therapy in Acute Ocular Chemical BurnsDebby Astasya AnnisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infectious DiseasesDocument5 paginiInfectious DiseasesShari' Si WahyuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pilot study tests accuracy of novel sensor for burn wound infection detectionDocument8 paginiPilot study tests accuracy of novel sensor for burn wound infection detectionMarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mm695152a3 HDocument6 paginiMm695152a3 HKinja NinjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artritis Séptica 27ago2023Document10 paginiArtritis Séptica 27ago2023José Alejandro Rivera JaramilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dini Berliana JurnalDocument15 paginiDini Berliana JurnalDini BerlianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rakhee Patel, Mark Gilchrist and Armando Gonzalez-Ruiz: Results Cont'd Candida Score' Cont'dDocument1 paginăRakhee Patel, Mark Gilchrist and Armando Gonzalez-Ruiz: Results Cont'd Candida Score' Cont'dntnquynhproÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toxicology Reports: SciencedirectDocument6 paginiToxicology Reports: SciencedirectNoNWOÎncă nu există evaluări

- FLCCC Summary of The Evidence of Ivermectin in COVID 19Document3 paginiFLCCC Summary of The Evidence of Ivermectin in COVID 19Muhamad ZaidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crs LinDocument4 paginiCrs LinPoolerErÎncă nu există evaluări

- AcneDocument4 paginiAcneLidwina DewiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Referensi 5Document5 paginiReferensi 5RizkaGayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piis0002939418302228 PDFDocument9 paginiPiis0002939418302228 PDFadistimayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endophthalmitis Patients Seen in A Tertiary Eye Care Centre in Odisha: A Clinico-Microbiological AnalysisDocument8 paginiEndophthalmitis Patients Seen in A Tertiary Eye Care Centre in Odisha: A Clinico-Microbiological AnalysisSurendar KesavanÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSY21 COST EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS OF EMICIZUMAB FOR THE TREATME - 2019 - Value IDocument1 paginăPSY21 COST EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS OF EMICIZUMAB FOR THE TREATME - 2019 - Value IMichael John AguilarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Lensa Kontak TerbaruDocument22 paginiJurnal Lensa Kontak TerbaruNiSa Ka Al-LuLuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immunologic Evaluation of Pediatric Chronic and Recurrent Acute RhinosinusitisDocument7 paginiImmunologic Evaluation of Pediatric Chronic and Recurrent Acute RhinosinusitisandiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Molecular DiagnosticsDocument19 paginiIntroduction To Molecular DiagnosticsJulian BarreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Primer - Fluconazole Versus Itraconazole in The Treatment of Tinea VersicolorDocument8 paginiJurnal Primer - Fluconazole Versus Itraconazole in The Treatment of Tinea VersicolorKopitesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article V2Document1 paginăArticle V2Natalia MaximoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Berende Ab CiDocument9 paginiBerende Ab CiDeaz Fazzaura PutriÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Clinical Relevance of Microbiology Specimens in Head and Neck Space Infections of Odontogenic OriginDocument3 paginiThe Clinical Relevance of Microbiology Specimens in Head and Neck Space Infections of Odontogenic OriginkaarlaamendezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nocardia Keratitis Clinical Course and TherapyDocument8 paginiNocardia Keratitis Clinical Course and TherapyAuroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- ESCMID Candida Guidelines Diagnostic ProceduresDocument10 paginiESCMID Candida Guidelines Diagnostic ProceduresiisisiisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal - Erin Puspasari - 30101507441Document7 paginiJurnal - Erin Puspasari - 30101507441EnErin AnindithaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Molecular, Serological, and Biochemical Diagnosis and Monitoring of COVID-19: IFCC Taskforce Evaluation of The Latest EvidenceDocument16 paginiMolecular, Serological, and Biochemical Diagnosis and Monitoring of COVID-19: IFCC Taskforce Evaluation of The Latest Evidenceabekhti abdelkaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mm7019a3 HDocument5 paginiMm7019a3 HShuvo H AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- CE (Ra) F (SH) PF1 (SY OM) PFA (OM) PN (KM)Document6 paginiCE (Ra) F (SH) PF1 (SY OM) PFA (OM) PN (KM)SUBHADIPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catgutpuntura Rinitis AlérgicaDocument11 paginiCatgutpuntura Rinitis AlérgicaDubichelÎncă nu există evaluări

- WJG 19 9003 PDFDocument10 paginiWJG 19 9003 PDFTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 PB PDFDocument11 pagini1 PB PDFTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADocument7 paginiATheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statin Use and The Risk of Dementia in Patients With Stroke: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort StudyDocument7 paginiStatin Use and The Risk of Dementia in Patients With Stroke: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort StudyTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Venkat Esh 2008Document10 paginiVenkat Esh 2008Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathophysiology of Empty Nose Syndrome: Contemporary ReviewDocument5 paginiPathophysiology of Empty Nose Syndrome: Contemporary ReviewTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chronic PancreatitisDocument23 paginiChronic PancreatitisAlvin YeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionDocument2 paginiJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Venkat Esh 2008Document10 paginiVenkat Esh 2008Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- 81 89 PDFDocument9 pagini81 89 PDFSuril VithalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- AC0100NAUV10NrHU0r0 Nl AdocsooNf crrsoNcvto l0 svlrv u010cDocument3 paginiAC0100NAUV10NrHU0r0 Nl AdocsooNf crrsoNcvto l0 svlrv u010cTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cellulitis 01Document3 paginiCellulitis 01Farid Fauzi A ManwanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medicine Card 2Document4 paginiMedicine Card 2Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learn Dengue Clinical Case ManagementDocument1 paginăLearn Dengue Clinical Case ManagementArdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Anatomy Essay Test QuestionsDocument2 paginiHuman Anatomy Essay Test QuestionsvelangniÎncă nu există evaluări

- History Taking Note CardDocument3 paginiHistory Taking Note Cardrmelendez001100% (1)

- Dissection Rules and ProceduresDocument1 paginăDissection Rules and ProceduresTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medicine Card 2Document1 paginăMedicine Card 2ladki6Încă nu există evaluări

- OSSIFIED LIGAMENTDocument3 paginiOSSIFIED LIGAMENTTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Osteology 1Document1 paginăOsteology 1Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Print Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsDocument10 paginiPrint Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book1 PDFDocument2 paginiBook1 PDFTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personal DevelopmentDocument2 paginiPersonal DevelopmentTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Print Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsDocument10 paginiPrint Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Setting and Reaching Academic GoalsDocument2 paginiSetting and Reaching Academic GoalsTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bls Skill SheetsDocument141 paginiBls Skill SheetsTheodore Liwongan100% (1)

- Document 1Document2 paginiDocument 1Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Aid SummaryDocument4 paginiFirst Aid SummaryTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Emergency Medical ServicesDocument129 paginiNational Emergency Medical ServicesTheodore Liwongan100% (1)

- MrdicDocument18 paginiMrdicpapa0011Încă nu există evaluări

- Mouth Throat Nose and Sinuses Assessment FindingsDocument5 paginiMouth Throat Nose and Sinuses Assessment FindingsChris SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discharge Planning FinalDocument3 paginiDischarge Planning FinalRae Marie AquinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- October 2023 PRC PLE Schedule and Reminders 2Document4 paginiOctober 2023 PRC PLE Schedule and Reminders 2TrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medtronic CoreValve 31mm BrochureDocument2 paginiMedtronic CoreValve 31mm BrochureWillyaminedadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SWOT AnalysisDocument3 paginiSWOT Analysisdadedidopyaaang100% (2)

- Pathology Lecture 7 - LiverDocument11 paginiPathology Lecture 7 - Livercgao30Încă nu există evaluări

- NCM 104 - Bag TechniqueDocument2 paginiNCM 104 - Bag TechniqueIrish Margareth AdarloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Breast Examination Prenatal PostpartumDocument2 paginiBreast Examination Prenatal PostpartumMaria Rose Ann YeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nims Tariff ListDocument54 paginiNims Tariff ListsreekanthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antibiotic Skin TestingDocument8 paginiAntibiotic Skin TestingFitz JaminitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discharge PlanDocument4 paginiDischarge PlanPaul Loujin LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ehaq 4TH Cycle Protocol Must PreparedDocument3 paginiEhaq 4TH Cycle Protocol Must PreparedMiraf Mesfin100% (2)

- Renal Calculi Lesson PlanDocument14 paginiRenal Calculi Lesson PlanVeenasravanthiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short Answer Questions AnaesthesiaDocument91 paginiShort Answer Questions AnaesthesiaMeena Ct100% (11)

- Nursing Process PsychiatricDocument13 paginiNursing Process PsychiatricamitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Checklist Form For Visitors: Nakaranas Ka Ba NG Mga Sumusunod: Oo HindiDocument2 paginiHealth Checklist Form For Visitors: Nakaranas Ka Ba NG Mga Sumusunod: Oo HindiCoin CharÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV DR Shilpa Kalra 2021Document10 paginiCV DR Shilpa Kalra 2021Shilpa Kalra TalujaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henrietta Lacks: Dr. Roz Iasillo Trinity High School River Forest, ILDocument13 paginiHenrietta Lacks: Dr. Roz Iasillo Trinity High School River Forest, ILRoz IasilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bupivacaine (Marcaine)Document2 paginiBupivacaine (Marcaine)Michalis SpyridakisÎncă nu există evaluări

- SeqdumpDocument7 paginiSeqdumpAnayantzin AyalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Herpes ZosterDocument42 paginiHerpes ZostermehranerezvaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital Healthcare Market Research 3Document33 paginiDigital Healthcare Market Research 3Nero AngeloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sigmoidoscopy: Presented by Kriti Adhikari Roll No: 17Document38 paginiSigmoidoscopy: Presented by Kriti Adhikari Roll No: 17sushma shresthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BPHS - 2010 - Final - Master Signed - PDF LatestDocument90 paginiBPHS - 2010 - Final - Master Signed - PDF LatestZakia RafiqÎncă nu există evaluări