Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

MangalorePopulationDiversity PDF

Încărcat de

Lokesh BangaloreTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

MangalorePopulationDiversity PDF

Încărcat de

Lokesh BangaloreDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Proceedings of the National Conference on Ecology, Sustainable Development and Wildlife

Conservation

Paper-1

AN ASSESSMENT OF MANGROVE DIVERSITY, MANGALORE,

KARNATAKA

S. Murugan and Usha Anandhi

Reproductive Physiology Unit, Department of Zoology, Bangalore University (Karnataka)

E-mail: muru3986@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION:

Mangroves are arboreal salt-tolerant flowering plants growing ideally in tropical and

subtropical regions (Ellison and Stoddart, 1991). The word "Mangrove" could mean the

ecosystem or a single plant (Tomlinson, 1986). A mangrove plants is shrub, palm, tree or fern

growing above mean sea level of marine coastal environments or estuaries exceeding a height

of half a meter (Duke, 1992). The mangrove ecosystem is distinguished from other plant

species by naming them as "Mangals" (Macnae, 1968). Mangrove ecosystem, due to the rich

biodiversity and unusual habitat, command a unique attention among the coastal

environments. This ecosystem holds diverse faunal and floral diversity because of their

effective interaction of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem. Mangroves apart from being

nurseries for number of economically important aquatic animals, support for microbial flora

growth and providing habitats to crustaceans, molluscs, reptiles, mammals and birds. They

also have tremendous social and ecological value providing income by collection of

molluscs, crustaceans, fish, fuel wood, charcoal, timber and wood chips. Mangrove

ecosystem has a key role in trapping of pollutants, coastal land stabilization by filtering

sediment and protection against natural calamities (Elizabeth McLeod and Rodney V. Salm-

2006).

Mangroves act as filter for land runoffs and green-walls for soil erosion, thus crucial

in stabilising the loose soil from high wind velocity, tidal surges and cyclonic storms (Rao

and Sastry, 1973 and Rao et. al., 1963). Around 80 mangroves species are found to be

distributed throughout the world (Saenger et al., 1983). Though mangrove distribution is

found over 112 countries (Naskar and Mandal, 1999) covering about 240 x 103 km2 (Lugo et

al. 1990 and Twilley et al. 1992), India has 2.66% of the world’s mangroves (Arun and Shaji,

2013), having fourth largest mangrove of 6749Km2. The mangroves are highly threatened

across the globe. There is very limited data on the availability and importance of mangroves

in South Canara, India, hence the present study was undertaken. The main objective of the

study is to assess the diversity of mangrove flora, which would help in deriving taxonomical

details based on species diversity, richness and evenness from the selected sites of

Mangalore.

MATERIALS AND METHOD:

Study area: Mangrove vegetation in India, particularly in Karnataka is found to be

distributed in Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Uttara Kannada with a coastal line of about

320kms. Dakshina Kannada district has four main rivers joining the Arabian Sea, namely

St.Joseph’s College (Autonomous) 6

Proceedings of the National Conference on Ecology, Sustainable Development and Wildlife

Conservation

Netravathi, Kumaradhara, Gurupura (Phalguni), Nandini (Pavanje) river. Among these rivers

Kumaradhara confluence with Netravathi at Uppinangady and continues as river Netravathi.

Whereas at Dakshina Kannada Gurupura and Netravathi confluence in Mangalore and

Pavanje confluence with Shambavi river of Udupi district at Mulki to join Arabian Sea. In the

present study the Netravathi - Gurupura estuarine complex (12.90052'68", 74.82013'58" to

12.82081'36", 74.85089'45"), Mangalore has been selected, geograpically located 352 kms

west of Bangalore and 54 kms south to Udupi.

Data Collection: The areas where the true mangroves exist were first identified in the

Netravathi - Gurupura estuary. The study area is divided into 5 sites (Figure A) for

identification and documentation of mangrove diversity. Site 1 and 2 are from Gurupura

estuary, site 3 and 4 are from Netravathi estuary and site 5 is close to estuarine mouth joining

Arabian Sea. Regular surveys were made along the study sites of the estuary to explore the

successful results of the true mangroves. The mangrove identifications were done during their

flowering and fruiting seasons and took photographs with the help of camera. The

nomenclature of the mangroves were done based on Gamble (1957) and Matthew (1983)

identification methods.

Figure A: Map of study site at Netravathi -Gurupura estuarine complex

Biodiversity indices such as diversity index, species richness index and evenness

index were calculated with the following standard formulae.

The diversity index was calculated using the Shannon - Wiener diversity index (H’) (Shannon

- Wiener, 1949).

H =− (Pi ∗ Ln(Pi))

Where, Pi = S / N, S = number of individuals of one species, N = total number of all

individuals in the sample and Ln = Natural logarithm

The species richness index was measured by using the Margalef’s species richness index (d')

(Margalef, 1958).

(S − 1)

d =

Ln(N)

St.Joseph’s College (Autonomous) 7

Proceedings of the National Conference on Ecology, Sustainable Development and Wildlife

Conservation

Where, S = total number of species, N = total number of individuals in the sample and Ln =

Natural logarithm

The evenness index was analysed by adopting the Pielou’s species evenness index (J’)

(Pielou, 1966).

H

J’ =

Ln(S)

Where, H' = Shannon -Wiener diversity index, S = total number of species in the sample and

Ln = Natural logarithm

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

In the present study eight true mangrove species (Figure B) have been identified and

documented from six families Avicenniaceae (46.60%), Rhizophoraceae (40.78%),

Lythraceae (4.85%), Euphorbiaceae (4.85%), Poaceae (1.94%) and Acanthaceae (0.97%) in

the Netravathi - Gurupura estuarine complex. The distribution of mangrove species in

different study sites are as shown in Table A. Among the different sites Avicennia officinalis

was found to be dominated in all the study sites, followed by Rhizophora mucronata,

Kandelia candel and Rhizophora apiculata which may be due to their tolerance to the wide

range fluctuations of physico - chemical properties. The important invader species of

mangrove ecosystem is Avicennia officinalis being of hardy in nature and high range of

adaptability and this was followed by Rhizophora sps (Arun and Shaji, 2013). Mangrove

diversity in the coast is usually an association of Rhizophora species with other mangrove

species as the soil is inundated daily two times by the sea water (Basha, 1992).

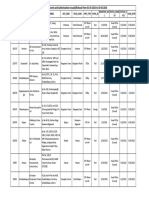

Table A: Distribution of mangroves in selected sites of Netravathi - Gurupura estuary

Botanical Name Site 1 Site 2 Site 3 Site 4 Site 5

Acanthus ilicifolius + - - - -

Avicennia officinalis + + + + +

Excoecaria agallocha - + - + -

Kandelia candel + + - + -

Porteresia coarctata + - - - -

Rhizophora apiculata + + - + -

Rhizophora mucronata + + + + -

Sonneratia alba + + + - -

St.Joseph’s College (Autonomous) 8

Proceedings of the National Conference on Ecology, Sustainable Development and Wildlife

Conservation

1.94 0.97

4.85% % %

4.85% Avicennia officinalis

Rhizophora apiculata

Rhizophora mucronata

13.59% Kandelia candel

46.60%

Sonneratia alba

Excoecaria agallocha

15.53% Porteresia coarctata

Acanthus ilicifolius

11.65%

Figure B: Percentage of mangroves species during the study period

Mangroves have high potential to get acclimatized to changes in the surrounding

environment. Out of the eight mangrove species Avicennia officinalis, Excoecaria agallocha,

Kandelia candel, Rhizophora apiculata, Rhizophora mucronata and Sonneratia alba were

identified as trees. One mangrove herb species namely Acanthus ilicifolius and one grass

namely Porteresia coarctata are reported from the present study (Table B). In our

investigation, Acanthus ilicifolius is found to be flowering from April to December and

fruiting during July to February and has been reported occurring in varied habitats of West

and East Coasts (Mudaliar et al, 1954). Avicennia officinalis flowered during June to

September and fruited during September to March. Kandelia candel was found to flower

from January to December with fruiting from April to January and this plant is found to be

very fast disappearing from the mangrove locations of Mangalore. Excoecaria agallocha and

Sonneratia alba flowered from February to July and fruited during June to January and

August to February respectively. Rhizophora apiculata and Rhizophora mucronata showed

flowering and fruiting simultaneously from July to October (Suma and Gowda, 2013).

Table B: Mangroves plants identified at Netravathi - Gurupura estuary.

Habit

Botanical Name Family Name

Acanthus ilicifolius Acanthaceae Herb

Avicennia officinalis Avicenniaceae Tree

Excoecaria agallocha Euphorbiaceae Tree

Kandelia candel Rhizophoraceae Tree

Porteresia coarctata Poaceae Grass

Rhizophora apiculata Rhizophoraceae Tree

Rhizophora mucronata Rhizophoraceae Tree

Sonneratia alba Lythraceae Tree

St.Joseph’s College (Autonomous) 9

Proceedings of the National Conference on Ecology, Sustainable Development and Wildlife

Conservation

Among the different study sites the Shannon-Wiener diversity index of mangrove

species showed highest at site 2 and lowest at site 5, Margalef’s richness index was noticed

highest at site 1 and lowest at site 5 and Pielou’s evenness index was observed highest at site

5 and lowest at site 3 (Table C). This may be attributed to the dominance of Avicennia

officinalis, Rhizophora sps. and physico-chemical properties of the study sites.

Table C: Diversity index, richness index and evenness index of mangroves at different study

sites during the study period. (H’ = Shannon-Wiener diversity index; d = Margalef’s species

richness index; J = Pielou’s evenness index)

Biodiversity indices Site - 1 Site - 2 Site - 3 Site – 4 Site - 5

Diversity index (H’) 1.623 1.691 0.684 1.336 0.000

Richness index (d) 1.716 1.443 0.910 1.259 0.000

Evenness index (J’) 0.724 0.904 0.660 0.761 1.000

The site 1 and 2 showed high level of diversity as well as richness located in

Gurupura estuary which might be due to slow flowing water and good amount of substratum.

Site 3 and 4 showed moderate level of diversity and richness, which could be due to the fast

flowing water and less amount of substratum at Netravathi estuary. Site 5 close to estuarine

mouth showed no diversity and richness but showed highest evenness as only Avicennia

officinalis was found distributed. The evenness in other sites varied in the order Site 2 > Site

4 > Site 1 > Site 3.

CONCLUSION:

In the present investigation, 8 species of true mangroves with 6 tree species, 1 herb

species and 1 grass species were identified from Netravathi - Gurupura estuarine complex,

Mangalore. Even though these mangroves protect human resource and biodiversity, these

ecosystem are experiencing enormous threat due to their tremendous exploitation for fuel

wood, timber, paper, charcoal, alcohol and medicine (Upadhyay et al. 2002). In the recent

times over 40% mangrove areas has been depleted (Satheesh Kumar et al, 2011) as increased

human settlement has increased pressure on these mangroves. Hence immediate conservation

activities towards the better management of remaining mangroves with legal enforcement of

protection rules are of at most need.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

The authors are grateful to Dr. S. Saraswathi, Assistant Professor, BMCRI, Bangalore

for the support provided in conducting the study.

St.Joseph’s College (Autonomous) 10

Proceedings of the National Conference on Ecology, Sustainable Development and Wildlife

Conservation

REFERENCE:

1. Arun. T. Ram and Shaji. C. S. 2013. Diversity and Distribution of Mangroves in

Kumbalam Island of Kerala, India. IOSR Journal Of Environmental Science,

Toxicology And Food Technology. Volume 4, Issue 4 (May. - Jun. 2013), PP 18-26.

2. Basha S.C. 1992. Mangroves of Kerala- A fast disappearing asset, Indian forester.

120(2), 175-189.

3. Duke N.C. 1992. Mangrove floristic and biogeography. Pp.63100 in Tropical

Mangrove Ecosystems. A.I. Robertson and D.M. Alongi, Eds. American Geophysical

Union, Washington DC., USA.

4. Elizabeth McLeod and Rodney V. Salm. 2006. Managing Mangroves for Resilience

to Climate Change. The World Conservation Union (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland.

5. Ellison J.C. and D.R. Stoddart. 1991. Mangrove ecosystem collapse during predicted

sea-level rise: Holocene analogues and implications. Journal of Coastal Research 7:

151-165.

6. Gamble J.S. 1957. Flora of the Presidency of Madras, Botanical Survey of India,

Calcutta.

7. Lugo A.E, Brown S and Brinson M.M. 1990. Concepts in Wetland Ecology. In: A.E.

Lugo, M.M. Brinson and S. Brown (eds). Amsterdam: Ecosystems of the World 15,

Forested Wetlands. Elsevier, 53-85.

8. Macnae W. 1968. A general account of the fauna and flora of mangrove swamps and

forests in the Indo-West-Pacific region. Advances in Marine Biology 6:73-270.

9. Margalef R. 1958. Temporal succession and spatial heterogeneity in phytoplankton.

In: Perspectives in Marine biology. Buzzati-Traverso (Ed.), The University of

California Press, Berkeley, p. 323-347.

10. Matthew K.M. 1983. The Flora of the Tamilnadu Carnatic, The Rapinat Herbarium,

Tiruchirapalli.

11. Mudaliar, Rajasekara C and Sunanda Kamath. 1954. Back water flora of the west

coast of South India, J.Bombay.Nat.Hist.Soc. 52.

12. Naskar K.R. and R.N. Mandal. 1999. Ecology and Biodiversity of Indian Mangroves.

Daya Publishing House, New Delhi, India.

13. Pielou E. C. 1966. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological

collections. J. Theor. Biol. 13: 131-144.

14. Rao T.A and Sastry A.R.K. 1973. Studies on the flora and vegetation of coastal

Andhra Pradesh, India, Bull. Bot.Surv. India, 15, 92 –107.

15. Rao T.A, Aggarwal K.R. and Mukherjee A.K. 1963. Ecological studies on the soil

and vegetation of Krusadi group of islands in the Gulf of Mannar. Bull. Bot. Surv.

India, 5, 141–148.

16. Saenger P, Hegerl EJ and Davie JDS. 1983. Global status of mangrove ecosystems.

The Environmentalist 3 (supplement 3).

17. Satheeshkumar P, Manjusha U. and Pillai N.G.K. 2011. Conservation of mangrove

forest covers in Kochi coast. Current Science. 101(11), 1400.

18. Shannon C. E. and W. Wiener. 1949. The mathematical theory of communication.

Urbana, University of Illinois Press. 177 pp.

St.Joseph’s College (Autonomous) 11

Proceedings of the National Conference on Ecology, Sustainable Development and Wildlife

Conservation

19. Suma and Gowda P.V. 2013. Diversity of Mangroves in Udupi District of Karnataka

State, India. International Research Journal of Biological Sciences. Vol. 2(11), 11-17.

20. Tomlinson P.B. 1986. The botany of mangroves. Cambridge University Press.

21. Twilley R.R, Chen R.H and Hargis T. 1992. Carbon sinks in mangroves and their

implications to carbon budget of tropical coastal ecosystems. Water, Air and Soil

Pollution, 64, 265-288.

22. Upadhyay V.P, Ranjan R. and Singh. J. S. 2002. Human mangrove conflicts: The way

out. Current Science 83: 1328-1336.

St.Joseph’s College (Autonomous) 12

St Joseph’s College (Autonomous)

Copyright St. Joseph’s College

Published by Saras Publication, Nagercoil

First Edition : 2017.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography or any

other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical,

without the written permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN No.: 978-93-86519-05-4

Price : Rs.450/-

Pages : 174

Published by

SARAS PUBLICATION

114/35G, A.R.P. Camp Road, Periavilai,

Kottar P.O., Nagercoil,

Kanyakumari Dist -629 002.

Telephone : 04652 265026

Fax : 04652 265099

Cell phone : 09842123441

Visit us : Website:www.saraspublication.com

Contact us : E-mail: info@saraspublication.com

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Karnataka HistoryDocument48 paginiKarnataka HistoryLokesh Bangalore71% (7)

- Core Connections Algebra: Selected Answers ForDocument10 paginiCore Connections Algebra: Selected Answers ForLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Microbial EcologyDocument5 paginiPrinciples of Microbial Ecologyvaibhav_taÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mutant Year Zero - Genlab Alpha - Paradise Valley Map ( - Oef - ) PDFDocument2 paginiMutant Year Zero - Genlab Alpha - Paradise Valley Map ( - Oef - ) PDFantonio santosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Urban IndiaDocument23 paginiUrban IndiaLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rural Infrastructure DevelopmentDocument961 paginiRural Infrastructure DevelopmentLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rural Infrastructure DevelopmentDocument961 paginiRural Infrastructure DevelopmentLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Addressing Non-Adherence To Antipsychotic Medication - A Harm-Reduction ApproachDocument12 paginiAddressing Non-Adherence To Antipsychotic Medication - A Harm-Reduction ApproachMatt AldridgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hosalli Poverty AnalysisDocument19 paginiHosalli Poverty AnalysisLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Development of Lean Assessment ModelDocument8 paginiDevelopment of Lean Assessment ModelLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yield Estimation of Coconut in Tumkur District of Karnataka: January 2016Document9 paginiYield Estimation of Coconut in Tumkur District of Karnataka: January 2016Lokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Issues Refused by State GovtDocument57 paginiIssues Refused by State GovtLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daily PrayersDocument11 paginiDaily Prayerssaurabh0015Încă nu există evaluări

- A Prayer To River KAverI SanskritDocument7 paginiA Prayer To River KAverI SanskritLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hydropower Generation Performance in Cauvery Basin: Projects Inst Capacity (MW) Generation (MU) Mu/MwDocument1 paginăHydropower Generation Performance in Cauvery Basin: Projects Inst Capacity (MW) Generation (MU) Mu/MwLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krishna River Basin Closing PDFDocument48 paginiKrishna River Basin Closing PDFLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sri Krishnaveni Mahatmyam: - P.R. KannanDocument9 paginiSri Krishnaveni Mahatmyam: - P.R. KannanLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kaveri RiverDocument14 paginiKaveri RiverLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Story of BAHUBALI & Xilinx FPGAsDocument2 paginiThe Story of BAHUBALI & Xilinx FPGAsRakib HasanÎncă nu există evaluări

- KarnatakaDocument1 paginăKarnatakaseenu189Încă nu există evaluări

- Gubbi Project PLanDocument16 paginiGubbi Project PLanLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- bb77 PDFDocument28 paginibb77 PDFLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tumkuru District PoliciesDocument12 paginiTumkuru District PoliciesLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ohio Colleges UniversitiesDocument1 paginăOhio Colleges UniversitiesLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- bb77 PDFDocument28 paginibb77 PDFLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes On Abstract Algebra 2013Document151 paginiNotes On Abstract Algebra 2013RazaSaiyidainRizviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math 2270-Last Homework Assignment: 1.1 GeneticsDocument1 paginăMath 2270-Last Homework Assignment: 1.1 GeneticsLokesh BangaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Telephone List - Tumkur District.Document9 paginiTelephone List - Tumkur District.Lokesh Bangalore100% (1)

- Gulbarga District, Karnataka: Ground Water Information BookletDocument24 paginiGulbarga District, Karnataka: Ground Water Information BookletLokesh Bangalore100% (1)

- Bush Fire Provisions - Landscaping and Property Maintenance Attachment - 20070301 - 0BBAC1FADocument6 paginiBush Fire Provisions - Landscaping and Property Maintenance Attachment - 20070301 - 0BBAC1FAmoneycycleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Placement: BROCHURE 2018-20Document24 paginiPlacement: BROCHURE 2018-20Salil PantÎncă nu există evaluări

- IndexDocument133 paginiIndexTaylor Smyth GordonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valuing and Managing The Philippines' Marine Resources Toward A Prosperous Ocean-Based Blue EconomyDocument26 paginiValuing and Managing The Philippines' Marine Resources Toward A Prosperous Ocean-Based Blue EconomyAna TolentinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ecotourism in Protected Area: An Assignment OnDocument11 paginiEcotourism in Protected Area: An Assignment OnJahidul hoqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Informational Passages RC - CactusDocument1 paginăInformational Passages RC - CactusandreidmannnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Env 203-2man & Env Issues - FALL - 13Document61 paginiEnv 203-2man & Env Issues - FALL - 13Nayeem FerdousÎncă nu există evaluări

- GAWA Year 12 Sem 1 2022 - Exam Marking Guide For Teachers OnlyDocument32 paginiGAWA Year 12 Sem 1 2022 - Exam Marking Guide For Teachers OnlysponÎncă nu există evaluări

- Linguistic Comparison of Semai DialectsDocument111 paginiLinguistic Comparison of Semai DialectsDavid BurtonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0118 Public Participation TransmissionDocument12 pagini0118 Public Participation TransmissionJo RajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 - The Problem and Its Setting Real Na RealDocument11 paginiChapter 1 - The Problem and Its Setting Real Na RealBryanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discount ComercialDocument12 paginiDiscount ComercialAdrianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainable Development Project Class 10th PDFDocument14 paginiSustainable Development Project Class 10th PDFSD P91% (22)

- Concept Paper-Climate ChangeDocument3 paginiConcept Paper-Climate ChangeKYLENE NANTONGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Awash - Water Allocation - Strategic Plan - June - 2017Document58 paginiAwash - Water Allocation - Strategic Plan - June - 2017MeklitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Earth First! Newsletter Zero (1983)Document8 paginiEarth First! Newsletter Zero (1983)Daniel FalbÎncă nu există evaluări

- E.V.S Unit 4 Biodiversity and ConservationDocument11 paginiE.V.S Unit 4 Biodiversity and ConservationSHIREEN TEKADEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Science and HealthDocument7 paginiDetailed Lesson Plan in Science and HealthCandace Wagner100% (25)

- Case Study of BrazilDocument4 paginiCase Study of Brazilcheetah128Încă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines For Adopting Multi Use of Stormwater Management FacilitiesDocument24 paginiGuidelines For Adopting Multi Use of Stormwater Management FacilitiesMohamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- M Kps Tree Planting ProjectDocument9 paginiM Kps Tree Planting ProjectTerriah AlonarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Day 2 Lesson PlanDocument7 paginiDay 2 Lesson Planapi-532490346Încă nu există evaluări

- 10.2305 IUCN - UK.2019-1.RLTS.T39994A115576640.en PDFDocument16 pagini10.2305 IUCN - UK.2019-1.RLTS.T39994A115576640.en PDFAjay SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Birds of Tifft by Jonathan Skinner Book PreviewDocument11 paginiBirds of Tifft by Jonathan Skinner Book PreviewBlazeVOX [books]Încă nu există evaluări

- Permaculture EbookDocument95 paginiPermaculture EbookfaroeldrÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20 Preg Unit 6 Nat Science 4º Eng-SpaDocument2 pagini20 Preg Unit 6 Nat Science 4º Eng-SpaenkarniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tci Progressive Era PresidentsDocument10 paginiTci Progressive Era Presidentsapi-328296165Încă nu există evaluări

- Carbayo & Marques - 2011Document2 paginiCarbayo & Marques - 2011Leonardo CottsÎncă nu există evaluări