Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cardio Vascular Mortality

Încărcat de

asdsadDrepturi de autor

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Cardio Vascular Mortality

Încărcat de

asdsadDrepturi de autor:

Articles

Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes

incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with

impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes

Prevention Study: a 23-year follow-up study

Guangwei Li, Ping Zhang, Jinping Wang, Yali An, Qiuhong Gong, Edward W Gregg, Wenying Yang, Bo Zhang, Ying Shuai, Jing Hong,

Michael M Engelgau, Hui Li, Gojka Roglic, Yinghua Hu, Peter H Bennett

Summary

Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol Background Lifestyle interventions among people with impaired glucose tolerance reduce the incidence of diabetes,

2014; 2: 474–80 but their effect on all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality is unclear. We assessed the long-term effect of

Published Online lifestyle intervention on long-term outcomes among adults with impaired glucose tolerance who participated in the

April 3, 2014

Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S2213-8587(14)70057-9

See Comment page 441 Methods The study was a cluster randomised trial in which 33 clinics in Da Qing, China—serving 577 adults with

Department of Endocrinology,

impaired glucose tolerance—were randomised (1:1:1:1) to a control group or lifestyle intervention groups (diet or

China-Japan Friendship exercise or both). Patients were enrolled in 1986 and the intervention phase lasted for 6 years. In 2009, we followed up

Hospital, Beijing, China participants to assess the primary outcomes of cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and incidence of diabetes

(Prof G Li MD, W Yang MD, in the intention-to-treat population.

B Zhang MD,

Y Shuai BD, J Hong MD);

Center of Endocrinology Findings Of the 577 patients, 439 were assigned to the intervention group and 138 were assigned to the control group

and Cardiovascular Disease, (one refused baseline examination). 542 (94%) of 576 participants had complete data for mortality and 568 (99%)

National Center of Cardiology contributed data to the analysis. 174 participants died during the 23 years of follow-up (121 in the intervention group vs 53

& Fuwai Hospital, Beijing,

China (G Li, Y An MD,

in the control group). Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular disease mortality was 11·9% (95% CI 8·8–15·0) in the

Q Gong MD); Division of intervention group versus 19·6% (12·9–26·3) in the control group (hazard ratio [HR] 0·59, 95% CI 0·36–0·96; p=0·033).

Diabetes Translation All-cause mortality was 28·1% (95% CI 23·9–32·4) versus 38·4% (30·3–46·5; HR 0·71, 95% CI 0·51–0·99; p=0·049).

(P Zhang PhD, E W Gregg PhD),

Incidence of diabetes was 72·6% (68·4–76·8) versus 89·9% (84·9–94·9; HR 0·55, 95% CI 0·40–0·76; p=0·001).

Center for Global Health

(M M Engelgau MD), Centers for

Disease Control and Interpretation A 6-year lifestyle intervention programme for Chinese people with impaired glucose tolerance can

Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA; reduce incidence of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality and diabetes. These findings emphasise the long-term

Department of Cardiology,

clinical benefits of lifestyle intervention for patients with impaired glucose tolerance and provide further justification

Da Qing First Hospital, Da Qing,

China (J Wang MD, H Li MD, for adoption of lifestyle interventions as public health measures to control the consequences of diabetes.

Y Hu MD); Department of

Management of Funding Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO, the China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Da Qing First Hospital.

Noncommunicable Diseases,

World Health Organization,

Geneva, Switzerland Introduction implications. We assessed such effects in people who

(G Roglic MD); and Phoenix Lifestyle interventions for people with impaired glucose participated in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study

Epidemiology and Clinical tolerance can delay or prevent the development of over a 23-year period.

Research Branch, National

diabetes and lead to improvements for other

Institute of Diabetes and

Digestive and Kidney Diseases, cardiovascular risk factors.1–11 However, whether these Methods

Phoenix, AZ, USA changes reduce the incidence of long-term complications, Study design and participants

(P H Bennett FRCP) and the excess cardiovascular disease and all-cause The design of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study and

Correspondence to: mortality that accompany diabetes is uncertain.12,13 In our the 20-year follow-up study have been reported pre-

Prof Guangwei Li, Department

previous analysis7 of 20-year follow-up data from the viously.1,7,14 In 1986, 33 primary care clinics in Da Qing,

of Endocrinology, 167 Beilishi

Road, Xicheng District, Beijing, Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study, we reported a China serving 577 people with impaired glucose tolerance

100037, China statistically insignificant 17% reduction in cardiovascular were enrolled into a cluster randomised trial. All patients

guangwei_li@medmail.com.cn disease mortality and a significantly lower incidence of treated at the clinics were eligible if they had impaired

Or severe diabetic retinopathy that seems to have been glucose tolerance in 1985. We did a 20-year follow-up

Dr Ping Zhang, Division of mediated primarily by delaying the onset of diabetes.14 study up to the end of 20067 and here report results after

Diabetes Translation, Centers for Because cardiovascular disease is the major cause of an additional 3 years. The institutional review boards of

Disease Control and Prevention,

4770 Buford HWY, NE, F-75

excess mortality in people with impaired glucose WHO and the China-Japan Friendship Hospital approved

Atlanta, GA 30341, USA tolerance, more definitive information about the effect of the protocol. All study participants, or their proxies who

pzhang@cdc.gov lifestyle intervention on cardiovascular disease and all- provided information about deceased participants, gave

cause mortality in such people has crucial public health written informed consent.

474 www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology Vol 2 June 2014

Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at University of Queensland Library from ClinicalKey.com.au by Elsevier on September 24, 2017.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2017. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Articles

Randomisation and masking any diabetes-related macrovascular or microvascular

Clinics were cluster randomised (1:1:1:1) to one of three complications. This report includes data for only the first

lifestyle interventions (25 clinics with a total of three because no new data for diabetes-related

439 people) or a control group (eight clinics with macrovascular and microvascular complications were

138 people). Of the 25 intervention clinics, nine collected at the 23-year follow-up.

(148 participants) were assigned to a diet only

intervention, nine clinics (155 participants) to an Statistical analysis

exercise only intervention, and seven clinics Power calculations were done for the original 6-year

(136 participants) to a diet plus exercise intervention. intervention trial. For the present study we estimated

The diet intervention was designed to produce weight minimal detectable differences. With an α of 0·05, we

loss in those who were overweight or obese, and to estimated that there was an 80% chance of detecting a

reduce simple carbohydrate and alcohol intake in people 43% reduction in all-cause mortality and a 63% reduction

of normal weight. The exercise intervention was in cardiovascular disease mortality when comparing the

designed to increase the leisure time spent doing control group with the combined lifestyle intervention

physical activity. groups.

All participants (including those at clinics in the control The observational period for mortality was from date of

group) received examinations at baseline, 2 years, 4 years, randomisation to date of death, loss to follow-up, or Dec 31,

and 6 years after randomisation and at 20-year and 2009, whichever came first. For diabetes incidence, the

23-year follow-up. Participants in the control group observational period was from the date of randomisation

received standard medical care. The interventions were to the date of diagnosis, or Dec 31, 2009, whichever came

delivered for 6 years (1986–92), after which all participants first. As the incidence of diabetes at both the end of the

were informed of the results and asked to continue with 6-year intervention period and the 20-year follow-up period

usual medical care. was similar in each of the three intervention groups, we

Investigators who assessed the outcomes at follow-up combined the intervention groups a priori to increase the

were masked to treatment allocation. Patients and other

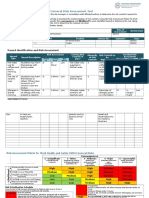

investigators were not masked. 577 patients enrolled in randomly assigned clinic

Procedures 1 refused baseline examination

We tried to follow up all the original study participants to

establish their vital status. For deceased participants, we

collected date and cause of death from death certificates, 438 in intervention group 138 in control group

reviews of medical records, and interviews with proxy

informants. We asked proxy informants about the date, 31 lost to 3 lost to

place, and circumstances of death along with information follow-up follow-up

about hospitals or physicians from whom the participant

had received care around the time of death. We obtained 407 assessed 135 assessed

medical records and death certificates and, together with

the informant interviews, they were reviewed and Figure 1: Trial profile

adjudicated independently by two doctors (JW and YA) to

establish the underlying cause of death. Disagreements

were resolved by a third senior physician (HL or YH). Intervention Control

group group

Causes of death were classified into two categories: (n=430) (n=138)

cardiovascular disease death (defined as death attributed

Sex

to coronary heart disease, stroke, or sudden death), and

Men 230 (53%) 79 (57%)

non-cardiovascular disease death (death from all other

Women 200 (47%) 59 (43%)

causes).

Age (years) 44·7 (9·3) 46·6 (9·3)

Diabetes was defined by 1985 WHO criteria with the

BMI (kg/m2) 25·7 (3·8) 26·2 (3·8)

results of oral glucose tolerance tests done every 2 years

Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) 132·4 (23·5) 134·4 (23·4)

between 1986 and 1992, and at the 20-year and 23-year

Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) 87·3 (14·5) 88·5 (13·5)

follow-up examinations,15 or from a report of physician-

diagnosed diabetes with evidence in the medical record FPG (mmol/L) 5·6 (0·8) 5·5 (0·8)

of high glucose concentrations, or use of hypoglycaemic 2hPG (mmol/L) 9·0 (0·9) 9·0 (16·1)

drugs, as described previously.7 Current smoker (%) 165 (38%) 69 (50%)

Data are n (%) or mean (SD). FPG=fasting venous plasma glucose. 2hPG=venous

Outcomes plasma glucose concentration 2 h after intake of 75 g oral glucose.

The four primary outcomes were all-cause mortality,

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

cardiovascular disease mortality, diabetes incidence, and

www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology Vol 2 June 2014 475

Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at University of Queensland Library from ClinicalKey.com.au by Elsevier on September 24, 2017.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2017. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Articles

statistical power to detect a mortality difference attributable Results

to the intervention. Mortality and diabetes incidence were Of the original 577 study participants, one declined the

calculated as the number of events divided by total person- baseline examination, eight had only a baseline

years since randomisation. examination, and 20 participants were lost to follow-up

We assessed cumulative all-cause and cardiovascular during the 6-year intervention period, mainly because of

mortality with the Kaplan-Meier method. We fitted a job relocation. During the subsequent 17 years after the

Weibull proportional hazards model16 with the SAS intervention, only six participants were lost to follow-up.

NLMIXED procedure for the primary analysis. The time Thus, 542 participants (94%) had complete data for

to all-cause and cardiovascular disease death or date of mortality and 568 (99%) contributed data to the analysis

diagnosis of diabetes was treated as the dependent (figure 1). 563 participants (98%) had complete data for

variable. Treatment group was included as a fixed effect diabetes incidence. Table 1 shows the baseline

and clinic was included as a random effect. No other characteristics.

covariates were adjusted for because the original study 174 participants died during the 23 years of follow-up

was a cluster randomised trial. We estimated hazard (121 in the intervention group and 53 in the control

ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs from the NLMIXED model. group). The cumulative incidence of all-cause death was

Differences were considered statistically significant if 28·1% (95% CI 23·9–32·4) in the intervention group

p<0·05 in two-sided tests. All primary analyses were for and 38·4% (95% CI 30·3–46·5) in the control group,

the intention-to-treat population. with an HR (adjusted for cluster randomisation) of 0·71

Mortality of people with and without diabetes varies (95% CI 0·51–0·99; p=0·049; table 2, figure 2). Few

greatly by sex and age.17–19 Therefore, we did post-hoc patients died during the first 10 years of the study, but

secondary analyses to assess the effect of intervention on the rates rose progressively thereafter (table 2, figure 2).

the primary outcomes of all-cause mortality and 78 participants died as a result of cardiovascular disease;

cardiovascular disease mortality separately in women 51 in the intervention group versus 27 in the control

and men. Because of an imbalance in the age distribution group. Cumulative incidences were 11·9% (95% CI

and smoking rates between men and women in the 8·8–15·0) versus 19·6% (95% CI 12·9–26·3; HR 0·59,

intervention and control groups, we adjusted for these 95% CI 0·36–0·96; p=0·03; table 2, figure 2). Significant

differences—as well as for the effect of delay in onset of differences between groups in the incidence of

diabetes—in post-hoc multivariable analyses with the diabetes—present at the end of the 6-year intervention

SAS NLMIXED procedure. We did the statistical analyses period and at 20-year follow-up1,7—persisted, with a

with SAS (version 9.1). cumulative incidence of 72·6% (95% CI 68·4–76·8) in

the intervention group and 89·9% (95% CI 84·9–94·9)

Role of the funding source in the control group (HR 0·55, 95% CI 0·40–0·76;

Employees of the study sponsors were involved in the p=0·001; table 2, figure 2).

study design; collection, analysis, interpretation of the Secondary post-hoc analyses stratified by sex and age

data; and the writing of the report. The corresponding showed substantial differences between women and

authors had full access to all data in the study and had men for the effect of intervention on all-cause and

See Online for appendix the final responsibility for the decision to submit for cardiovascular disease mortality (table 3, appendix).

publication. Among women, the cumulative incidence of all-cause

Intervention group Control group Hazard ratio p value

(n=430) (n=138) (95% CI)

All-cause mortality

Deaths 121 (28%) 53 (38%) ·· ··

Deaths per 1000 person-years (95% CI) 14·3 (11·8–16·9) 19·9 (14·5–25·2) ·· ··

Cumulative incidence (%; 95% CI) 28·1% (23·9–32·4) 38·4% (30·3–46·5) 0·71 (0·51–0·99) 0·049

Cardiovascular disease mortality

Deaths 51 (12%) 27 (20%) ·· ··

Deaths per 1000 person-years (95% CI) 6·0 (4·4–7·7) 10·1 (6·3–14·0) ·· ··

Cumulative incidence (%; 95% CI) 11·9% (8·8–15·0) 19·6% (12·9–26·3) 0·59 (0·36–0·96) 0·033

Diabetes incidence

Cases of diabetes 312 (73%) 124 (90%) ·· ··

Cases per 1000 person-years (95% CI) 73·2 (65·1–81·3) 122·9 (101·3–144·5) ·· ··

Cumulative incidence (%; 95% CI) 72·6% (68·4–76·8) 89·9% (84·9–94·9) 0·55 (0·40–0·76) 0·001

Data are n (%) unless stated otherwise. Hazard ratios adjusted by clinic.

Table 2: Effect of lifestyle intervention on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, and diabetes (1986–2009)

476 www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology Vol 2 June 2014

Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at University of Queensland Library from ClinicalKey.com.au by Elsevier on September 24, 2017.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2017. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Articles

mortality in the control group was almost double that in

the intervention group (table 3) and cardiovascular A

45 Control group

disease mortality showed a similar pattern (table 3). Intervention group

40

Conversely, for men, the intervention had no significant

Proportion of participants (%)

effect on either all-cause mortality or cardiovascular 35

disease mortality (table 3), although the reduction in 30

diabetes incidence was much the same in men and 25

women (table 3).

20

A greater proportion of men than women were smokers

(61% vs 16%) and mean age in the control group was 15

higher for men than for women (appendix). A higher 10

percentage of women were smokers in the control 5

HR 0·71, 95% CI (0·51–0·99)

compared with the intervention group (appendix). We 0

did a post-hoc multivariable analysis to test whether such 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 23

differences in baseline characteristics could account for Number at risk

the overall reduction of mortality and differences in the Control group 138 137 135 130 127 118 113 108 103 99 95 84 82

Intervention 438 426 412 395 384 373 364 355 338 321 305 290 286

effectiveness of the intervention between the sexes group

(appendix). However, after adjustment for age, sex,

smoking and the interaction between sex and B

25

intervention , the effect of lifestyle intervention remained

significant for both all-cause and cardiovascular disease

Proportion of participants (%)

20

mortality, suggesting that differences in baseline

characteristics did not account for the differences.

15

Because lifestyle intervention delays the onset of

diabetes and reduces the incidence of diabetes, we

10

assessed how mortality was affected by the time free

from diabetes, which was defined as the time between

randomisation and onset of diabetes (appendix). 5

Increased delay in the onset of diabetes was associated HR 0·59, 95% CI (0·36–0·96)

with significantly lower all-cause and cardiovascular 0

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 23

disease mortality. After inclusion of time to onset of

diabetes in the multivariable models the intervention Number at risk

Control group 138 137 135 130 127 118 113 108 103 99 95 84 82

variable was no longer statistically significant, suggesting Intervention 438 426 412 395 384 373 364 355 338 321 305 290 286

that the reduction in mortality associated with the group

intervention is mediated by its effect in delaying the C

onset of diabetes. 100

90

Discussion 80

This study is the first randomised clinical trial to show

Proportion of participants (%)

70

that lifestyle intervention in people with impaired

glucose tolerance reduces all-cause and cardiovascular 60

disease mortality (panel). These findings seem to mainly 50

be a result of lower mortality among women in the

40

intervention group. The Malmo study13 showed lower

mortality over a 12-year period in men with impaired 30

glucose tolerance treated with lifestyle intervention 20

compared with a group who received routine treatment,

10

but the study was not randomised. Other lifestyle HR 0·55, 95% CI (0·40–0·76)

studies—such as the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study2 0

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 23

and the Diabetes Prevention Program3—consistently

showed that a lifestyle intervention could reduce the Follow-up (years)

Number at risk

incidence of diabetes and decrease other cardiovascular Control group 138 105 69 48 40 37 34 27 27 23 14 13 13

disease risk factors8,10,11,13 but have not reported a reduction Intervention 438 387 314 250 230 206 192 161 147 136 114 114 114

group

in the incidence of all-cause and cardiovascular disease

mortality. Moreover, in the Look AHEAD study,23 a Figure 2: Cumulative incidence of (A) all-cause mortality, (B) cardiovascular disease mortality, and (C)

lifestyle intervention designed to produce weight loss in diabetes incidence over the 23-year follow-up (1986–2009)

obese or overweight people with diabetes did not HR=hazard ratio.

www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology Vol 2 June 2014 477

Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at University of Queensland Library from ClinicalKey.com.au by Elsevier on September 24, 2017.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2017. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Articles

Women Men

Control group Intervention group Hazard ratio p value Control group Intervention group Hazard ratio p value

(n=59) (n=200) (95% CI)* (n=79) (n=230) (95% CI)*

All-cause mortality

Number of deaths 17 30 ·· ·· 36 91 ·· ··

Deaths per 1000 person-years (95% CI) 14·1 (7·4–20·8) 7·4 (4·7–10·0) ·· ·· 24·7 (16·6–32·7) 20·8 (16·6–25·1) ·· ··

Cumulative incidence (%; 95% CI) 28·8% (17·2–40·4) 15·0% (10·1–19·9) 0·46 (0·24–0·87) 0·02 45·6% (34·6–56·6) 39·6% (33·3–45·9) 0·97 (0·65–1·46) 0·9

Cardiovascular disease mortality

Number of deaths 10 12 ·· ·· 17 39 ·· ··

Deaths per 1000 person-years (95% CI) 8·3 (3·2–13·4) 3·0 (1·3–4·6) ·· ·· 11·6 (6·1–17·2) 8·9 (6·1–11·7) ·· ··

Cumulative incidence (%; 95% CI) 17·0 (7·4–26·6) 6·0 (2·7–9·3) 0·28 (0·11–0·71) 0·01 21·5 (12·5–30·5) 17·0 (12·2–21·8) 0·91 (0·50–1·65) 0·7

Diabetes incidence

Number with diabetes 55 148 ·· ·· 69 164 ·· ··

Cases per 1000 person-years (95% CI) 128·5 (94·5–162·5) 74·9 (62·8–86·9) ·· ·· 118·8 (90·7–146·8) 71·8 (60·8–82·8) ·· ··

Cumulative incidence (%; 95% CI) 93·2 (86·7–99·7) 74·0 (67·9–80·1) 0·55 (0·35–0·87) 0·006 87·3 (80·0–94·6) 71·3 (65·4–77·2) 0·56 (0·39–0·81) 0·004

*Adjusted for randomisation by clinic and age.

Table 3: Effect of lifestyle intervention on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, and diabetes in women and men (1986–2009)

study, a difference in cardiovascular disease mortality

Panel: Research in context between the intervention and control group started to

emerge 12 years after the study began, slowly increased

Systematic review

to a 17% difference by the 20-year follow-up,7 but became

Three systematic reviews20–22 of randomised controlled clinical trials have assessed the

statistically significant only after 23 years (figure 2).

effects of lifestyle intervention on prevention of type 2 diabetes for people with impaired

The reduction in mortality mainly occurred in women;

glucose tolerance. They show that dietary or physical activity interventions reduce the

the intervention seemed to have little effect in men,

incidence of diabetes, not only during the period of active intervention,20 but also for

despite similar reductions in the incidence of diabetes.

many years afterwards: for 13 years or more in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention study,11 at

The prevalence of smoking at baseline was much higher

least 10 years in the US Diabetes Prevention Program,8 and 20 years in the Da Qing

for men than for women, and epidemiological analysis of

Diabetes Prevention Study.7 Lifestyle interventions for people with impaired glucose

the whole study population showed that smoking

tolerance are also associated with amelioration of some cardiovascular risk factors such as

increased the risk of all-cause death by almost 50% (data

blood pressure and concentrations of HDL and LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides.10 The risk

not shown). Nevertheless, adjustment for imbalances in

of death for people with type 2 diabetes is about twice that of people of a similar age who

smoking and age did not account for the apparent sex

do not have diabetes. A key question is whether or not lifestyle intervention to prevent or

differences in mortality, nor did this adjustment eliminate

delay the onset of diabetes can lower this excess mortality risk in people with impaired

the overall beneficial effect of the intervention. Poorer

glucose tolerance. However, to date, no randomised clinical trials have reported a

compliance with lifestyle intervention by men than by

significant reduction for either cardiovascular disease mortality or all-cause mortality.21,22

women, or differences in unmeasured confounders,

Interpretation might also have contributed to more favourable outcomes

Our study shows that a 6-year period of lifestyle intervention in Chinese people with for women. We have been unable to establish any

impaired glucose tolerance reduced the incidence of diabetes over a protracted period, definitive reasons for differences in the effect of the

and was ultimately associated with a significant reduction in total and cardiovascular intervention on mortality between men and women.

disease mortality. This reduction in mortality seems to be partly mediated by a delay in Our study has several strengths. First, individuals with

onset of diabetes. These findings provide yet further justification to implement lifestyle impaired glucose tolerance were recruited by screening a

interventions for people with impaired glucose tolerance as clinical and public health well-defined population and most people who were

measures to control the long-term consequences of diabetes. screened were enrolled in the trial.1 Consequently, the

findings are probably generalisable to most people in

significantly reduce cardiovascular disease events or China with impaired glucose tolerance. Second,

cardiovascular disease mortality. A key difference randomisation by clinic rather than by the individual

between these studies and the Da Qing Diabetes minimises the likelihood of contamination between the

Prevention Study is the length of follow-up; in previous intervention and control groups. Our primary analyses

studies, the length of follow-up might have been were adjusted to control for the cluster randomisation.

insufficient to detect an effect of intervention on Third, follow-up for mortality is very high (94%), reducing

mortality. Although the association between duration of non-response bias. Of the 35 participants who were lost to

diabetes and mortality is well established, serious chronic follow-up, 29 were lost during the initial active

complications and excess mortality typically only occur intervention phase of the study mainly because of

after at least 10 years of having diabetes.24–28 In the present relocation for work and migration from Da Qing. Fourth,

478 www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology Vol 2 June 2014

Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at University of Queensland Library from ClinicalKey.com.au by Elsevier on September 24, 2017.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2017. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Articles

all participants received usual care from the primary care 5·1 million excess deaths and at least US$548 billion in

clinics in a single health-care system in Da Qing, which health-care expenditure in 2013.33 Our findings imply

was provided by the state-run oil company. This reduces that implementation of lifestyle intervention for people

the likelihood that variations in medical care could have with impaired glucose tolerance—especially women—

biased the results. Fifth, diabetes incidence, mortality, who are at high risk for diabetes in China, or elsewhere,

and causes of death were assessed systematically. would reduce the incidence of diabetes and associated

Diabetes was assessed by oral glucose tolerance test every health-care expenditure, eventually resulting in a lower

2 years during the 6-year intervention period and at the number of diabetes-related deaths.

20-year and 23-year follow-up examinations, and then Contributors

systematically measured, albeit by conventional clinical GL coordinated and designed the study, acquired funding, collected data,

methods, for the remainder of the follow-up period. did the statistical analysis, and wrote the report. PZ coordinated and

designed the study, acquired funding, did the statistical analysis, and

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the follow-up wrote the report. JW and QG designed the study, collected data, and did

period lasted for 23 years, providing enough time for the the statistical analysis. YA collected data and did the statistical analysis.

development of the chronic complications of diabetes and EWG and MME designed the study, acquired funding, did the statistical

a sufficient number of deaths to enable us to detect analysis, and wrote the report. WY designed the study. BZ, YS, JH, and

HL collected data. GR designed the study and acquired funding. YH

differences in mortality between the control and designed the study and collected data. PHB designed the study, did the

intervention groups. statistical analysis, and wrote the report.

The study has some important limitations. First, Declaration of interests

because of the small size of the original trial, we combined We declare that we have no competing interests.

the three intervention groups to provide sufficient power. Acknowledgments

Second, different methods of follow-up were used during Supported by CDC/WHO Cooperative Agreement No. U58/

the 6 years of active intervention compared with the CCU424123-01-02 and the China-Japan Friendship Hospital. We thank

subsequent years. Nevertheless, the baseline and follow- the participants in the original Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study and

their proxies who contributed to the follow-up study. We also thank

up assessments were systematic and identical in the Lingzhi Kong, China Ministry of Health, the leadership at the

control and intervention groups. Third, not all deaths China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Da Qing First Hospital, the Da Qing

were documented by death certificate. However, death City Health Bureau, and the Beijing and West Pacific Regional Office of

WHO for their general support. We thank Xilin Yang (Tianjin Medical

was ascertained from hospital records for more than 90%

University), Yang Yang (National Center of Cardiology and Fuwai

of those who died. This method has been used Hospital, China), and Ted Thompson (Centers for Disease Control and

successfully in other studies29,30 of mortality in low-income Prevention, USA) for statistical advice. Our special thanks go to the late

and middle-income countries. Fourth, the study was Prof Xiaoren Pan as this study would not have been possible without

his leadership in the design and implementation of the original

originally designed and powered to establish whether a

Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study. The contents of this report are

lifestyle intervention could reduce the incidence of solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent

diabetes over a 6-year period. Only later, after this the official positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

hypothesis had been proven, was the follow-up phase the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases,

or WHO.

designed. Consequently, we lack systematic information

about changes in behaviour and cardiovascular risk References

1 Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in

factors such as smoking habits, blood pressure, serum preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The

cholesterol concentration, and drug use beyond the 6-year Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 537–44.

active intervention phase. This shortcoming limits our 2 Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2

diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with

ability to investigate possible explanatory variables. impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343–50.

However, the primary analyses based on the initial cluster 3 Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the

randomisation of participants are robust and only used incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or

metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393–403.

information for mortality outcomes that can be obtained

4 Ratner R, Goldberg R, Haffner S, et al. Impact of intensive lifestyle

reliably in retrospect from death certificates, medical and metformin therapy on cardiovascular disease risk factors in the

records, and informant interviews. diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 888–94.

This study is the first to show that lifestyle intervention 5 Kosaka K, Noda M, Kuzuya T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by

lifestyle intervention: a Japanese trial in IGT males.

in people with impaired glucose tolerance can both Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005; 67: 152–62.

reduce the incidence of diabetes and decrease mortality, 6 Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, Mukesh B, Bhaskar AD,

and so it has important implications for public health Vijay V. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that

lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in

policy about diabetes prevention in China and worldwide. Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1).

In China, as elsewhere, the health and economic burdens Diabetologia 2006; 49: 289–97.

of diabetes are large and growing. In 2008, an estimated 7 Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle

interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes

92 million adults in China (9·7% of the adult population) Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet 2008;

had diabetes and 148 million (15·5%) had prediabetes.31 371: 1783–89.

A more recent study reports an even larger estimate of 8 Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of

diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention

113·9 million (11·6% of adults) with diabetes in 2010.32 Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009; 374: 1677–86.

Worldwide, diabetes was estimated to be responsible for

www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology Vol 2 June 2014 479

Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at University of Queensland Library from ClinicalKey.com.au by Elsevier on September 24, 2017.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2017. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Articles

9 Saito T, Watanabe M, Nishida J, et al. Lifestyle modification and 20 Yamaoka K, Tango T. Efficacy of lifestyle education to prevent type 2

prevention of type 2 diabetes in overweight Japanese with impaired diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

fasting glucose levels: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2780–86.

Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 1352–60. 21 Hopper I, Billah B, Skiba M, Krum H. Prevention of diabetes and

10 Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Long-term effects reduction in major cardiovascular events in studies of subjects with

of the Diabetes Prevention Program interventions on cardiovascular prediabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled clinical trials.

risk factors: a report from the DPP Outcomes Study. Diabet Med Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011; 18: 813–23.

2013; 30: 46–55. 22 Yoon U, Kwok LL, Magkidis A. Efficacy of lifestyle interventions

11 Lindstrom J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, et al. Improved lifestyle and in reducing diabetes incidence in patients with impaired glucose

decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the tolerance: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

randomised Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS). Diabetologia Metabolism 2013; 62: 303–14.

2013; 56: 284–93. 23 Wing RR, Reboussin D, Lewis CE. Intensive lifestyle intervention

12 Uusitupa M, Peltonen M, Lindstrom J, et al. Ten-year mortality and in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 2358–59.

cardiovascular morbidity in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention 24 Knowler WC, Sartor G, Melander A, Schersten B. Glucose tolerance

Study--secondary analysis of the randomized trial. PLoS One 2009; and mortality, including a substudy of tolbutamide treatment.

4: e5656. Diabetologia 1997; 40: 680–86.

13 Eriksson KF, Lindgarde F. No excess 12-year mortality in men 25 Kim NH, Pavkov ME, Looker HC, et al. Plasma glucose regulation

with impaired glucose tolerance who participated in the Malmo and mortality in pima Indians. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 488–92.

Preventive Trial with diet and exercise. Diabetologia 1998; 26 Brun E, Nelson RG, Bennett PH, et al. Diabetes duration and

41: 1010–16. cause-specific mortality in the Verona Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care

14 Gong Q, Gregg EW, Wang J, et al. Long-term effects of a 2000; 23: 1119–23.

randomised trial of a 6-year lifestyle intervention in impaired 27 Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year

glucose tolerance on diabetes-related microvascular complications: follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes.

the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 1577–89.

Diabetologia 2011; 54: 300–07.

28 Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Solomon CG, et al. The impact of diabetes

15 WHO Study Group. Diabetes Mellitus. Report of a WHO Study mellitus on mortality from all causes and coronary heart disease in

Group. 727, 1–113; Geneva: World Health Organization, 1985. women: 20 years of follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 1717–23.

16 Collett D. Modeling survival data in medical research. London: 29 Gajalakshmi V, Peto R. Commentary: verbal autopsy procedure for

Chapman & Hall, 1994. adult deaths. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 748–50.

17 Barnett KN, Ogston SA, McMurdo ME, Morris AD, Evans JM. 30 Yang G, Rao C, Ma J, et al. Validation of verbal autopsy procedures

A 12-year follow-up study of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality for adult deaths in China. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 741–48.

among 10,532 people newly diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes in

31 Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and

Tayside, Scotland. Diabet Med 2010; 27: 1124–29.

women in China. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1090–101.

18 Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. Diabetes mellitus,

32 Xu Y, Wang L, He J, et al. Prevalence and control of diabetes in

fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med 2011;

Chinese adults. JAMA 2013; 310: 948–59.

364: 829–41.

33 International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas, 5th edn.

19 Sievers ML, Nelson RG, Knowler WC, Bennett PH. Impact of

Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2011.

NIDDM on mortality and causes of death in Pima Indians.

Diabetes Care 1992; 15: 1541–49.

480 www.thelancet.com/diabetes-endocrinology Vol 2 June 2014

Downloaded for Anonymous User (n/a) at University of Queensland Library from ClinicalKey.com.au by Elsevier on September 24, 2017.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2017. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Pangmalakasan NP1Document134 paginiPangmalakasan NP1MikEeAyanEsterasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Influencing HIV Disclosure Among People Living With HIV/AIDS in Nigeria: A Systematic Review Using Narrative Synthesis and Meta-AnalysisDocument16 paginiFactors Influencing HIV Disclosure Among People Living With HIV/AIDS in Nigeria: A Systematic Review Using Narrative Synthesis and Meta-AnalysisTrisna SariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Obstetric PatientDocument19 paginiCase Study Obstetric PatientPrinz Lozano100% (1)

- LabCorp+Virology+Report+Quantitative+RNA CDocument5 paginiLabCorp+Virology+Report+Quantitative+RNA CSooah ParkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Training BrochureDocument60 paginiTraining BrochureAbdur RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sewage-Treatment Plant PDFDocument3 paginiSewage-Treatment Plant PDFBanhisikha Goswami OfficialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Negative AutopsyDocument21 paginiNegative Autopsydr rizwanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toronto CA - Rest of The World Should Learn From Canada-Toronto CA (2023)Document3 paginiToronto CA - Rest of The World Should Learn From Canada-Toronto CA (2023)haroldpsbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cancer Prevention & Screening GuideDocument56 paginiCancer Prevention & Screening Guidenoorulzaman84Încă nu există evaluări

- Paediatric tuberculosis assessment scoresDocument1 paginăPaediatric tuberculosis assessment scoresGalaleldin AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCOS Factors BacolodDocument3 paginiPCOS Factors BacolodPrincess Faniega SugatonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Assessment Grandparents DayDocument5 paginiRisk Assessment Grandparents Dayapi-436147740Încă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Branding in PublicDocument16 paginiThe Role of Branding in PublicUsamah HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiological Tools: Fractions, Measures of Disease Frequency and Measures of AssociationDocument16 paginiEpidemiological Tools: Fractions, Measures of Disease Frequency and Measures of AssociationJerry Sifa0% (1)

- Should Minors Be Able To Purchase Birth Control Without Parental ConsentDocument4 paginiShould Minors Be Able To Purchase Birth Control Without Parental ConsentjohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hygiene PresentationDocument21 paginiHygiene Presentationproject_genomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal Bhs Inggris 1 PerbaikanDocument7 paginiSoal Bhs Inggris 1 PerbaikanNurul LailiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrients: On The Reporting of Odds Ratios and Risk RatiosDocument2 paginiNutrients: On The Reporting of Odds Ratios and Risk Ratiosfatihatus siyadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHE135 - Ch1 Intro To Hazard - MII - L1.1Document26 paginiCHE135 - Ch1 Intro To Hazard - MII - L1.1SyafiyatulMunawarahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indiviual Rack: ProvidedDocument4 paginiIndiviual Rack: Providedkevin tomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caring For Vulnerable Populations During A Pandemic: Literature ReviewDocument6 paginiCaring For Vulnerable Populations During A Pandemic: Literature ReviewMohamed AbdulqadirÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPH 596 Lecture 1 September 7 2018Document28 paginiSPH 596 Lecture 1 September 7 2018Kevin Rosen CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imci Quiz 1Document2 paginiImci Quiz 1Neptali Cardinal100% (1)

- STD PreventionDocument12 paginiSTD Preventionapi-370125730Încă nu există evaluări

- 2019-20 Handbook CatalogDocument254 pagini2019-20 Handbook CatalogGH PractitionerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hafiya Kezia - COVIDDocument2 paginiHafiya Kezia - COVIDHafiya KeziaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Sanitation and Hygiene UnderstandingDocument4 paginiWater Sanitation and Hygiene UnderstandingGreen Action Sustainable Technology GroupÎncă nu există evaluări

- FOOD SAFETY & GMP (Refresher Course) 2018Document156 paginiFOOD SAFETY & GMP (Refresher Course) 2018QA SpicemixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Part4 Evidence1 CozineDocument2 paginiPart4 Evidence1 Cozineapi-286143658Încă nu există evaluări

- Hospital Acquired Infections:: Yesterday, Today & TomorrowDocument87 paginiHospital Acquired Infections:: Yesterday, Today & TomorrowSharad BhallaÎncă nu există evaluări