Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ravelli OlympicShop2000 PDF

Încărcat de

Cláudia PoncianoTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ravelli OlympicShop2000 PDF

Încărcat de

Cláudia PoncianoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270479249

Beyond shopping: Constructing the Sydney

Olympics in three-dimensional text

Article in Text - Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse · January 2000

DOI: 10.1515/text.1.2000.20.4.489

CITATIONS READS

14 49

1 author:

Louise J. Ravelli

UNSW Sydney

27 PUBLICATIONS 301 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Editorial Board "Visual Communication" View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Louise J. Ravelli on 28 August 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Beyond Shopping: Constructing the

Sydney Olympics in three-dimensional text

LOUISE J. RAVELLI

Abstract

The Sydney 2000 Olympic Games were 'sold' to local and international

populations through a ränge ofmedia, including the Sydney Olympic Store,

an extravagant souvenir shop. The störe intertwines a ränge of semiotic

resources—layout, color, language, andmore—to create a meaningful text.

The article uses a social-semiotic framework to begin to explore the

ideational, interpersonal and textual meanings made in this störe, and

to problematize descriptions of multimodal texts, introducing intersemiosis

äs a key to the 'textuality' of these complex texts. It is argued that the

störe is much more than just a place to shop; through a ränge of devices,

it is situated within broader socioculturalframeworks, andclearly articulates

with existing ideologies surrounding the International Olympic Games.

Whilst highly preliminary in terms of analysis, the article suggests

some starting points for the description and critique of institutionalized,

multimodal texts.

Keywords: multimodal; systemic-functional; social semiotic;

intersemiosis; museum; ideology.

1. Introduction

As Sydney, Australia, prepared for the Olympic Games in the year 2000,

much was invested in pre-Games publicity, to attract international

visitors, to 'seil' local populations the advantages of the Games, and

to literally construct the Games in discursive terms. One particularly

interesting site for these processes has been the Olympic Store, an

extravagant souvenir shop located in the heart of Sydney's CBD (central

business district). This störe, äs reported in the Sydney Morning Herold

by Leo Schofield, a high-profile Sydney arts critic, was 'fabulous' in its

design conception, integrating image, color, spatial layout, language, and

0165-4888/00/0020-0489 Text 20(4) (2000), pp. 489-515

© Walter de Gruyter Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

490 Louise J. Ravelli

more to provide a coherent and persuasive text in relation to the Olympic

Games. Created by Saunders Design, a Sydney Company, the störe

generated something much more than a Shopping experience; even more

so than familiär 'lifestyle' Stores such äs Ikea. The design practices

deployed in the störe naturalized its content and invited identification with

the ideals of the International Olympic Games, creating, at least for

the compliant reader, positive affect towards the Games. In addition, the

störe constructed its own cultural significance through overt intertextual

references to the display practices of museums. How did it do all of this?

How did the störe create the meaning that it was—apparently—some-

thing more than a place to spend money on Souvenirs several years

prior to the event even taking place? What other sorts of meanings

were generated? How did all of its different design elements converge to

make a multimodal text? Using the social-semiotic framework of Halliday

(1978), Kress (1989 [1985]), Kress and Hodge (1988), and recent work of

Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) on the analysis of images, this article will

explore these questions, and relate the answers to a critique of the broader

cultural and ideological frameworks within which the störe operates. This

article is only preliminary and does not undertake a micro-level analysis

of the semiotic processes at stake; for examples of such analyses, however,

see Martin (1997), Mclnnes (1998), Martinec (in press, 1998), and OToole

(1992). The article will draw on the principle of foregrounding (Halliday

1973) to analyze the macro-semiotic processes in Operation within the

störe. It will be argued that the störe is clearly located within discursive

elements already recognized äs common to the representation of the

International Olympic Games. In contrast to other Olympic-related

sites, such äs the visitors' center at Homebush Bay (the actual location

of—much of—the Sydney Olympic Games), local concerns are addressed

only tangentially.

2. The störe in brief

The entrance to the Olympic Store is located in Pitt Street, Sydney,

a former thoroughfare for vehicles now reserved for pedestrians. It is the

shoppers' heart of the CBD, close to the two largest department Stores and

numerous malls and specialty shops. The Store itself is Underground, and

is entered by escalators. It sells promotional merchandise for the 2000

Olympics: hats, T-shirts, sporting goods and so on, äs well äs considerably

more expensive items, such äs ceramics and leather goods. Even though

Underground, there is no sense of closure about the space; the störe

conveys a sense of both significant breadth, with open vistas through its

various sections, and depth, with the escalators reaching up to street level

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 491

and a kind of 'pit' in the middle, which can be surveyed from above and

houses a large video screen. The merchandise is arranged in various

thematically grouped sections around the circumference of the pit; for

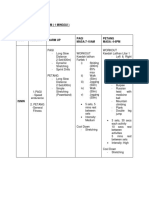

a simple schematic sketch of the störe's layout see Figure 1. Readers

should note that in a more recent arrangement of the störe the pit was

removed altogether, the floor restored to one uniform level, and further

goods displayed in this recovered space.

Inside, the design äs a whole contributes to a sense of quality and

luxury. There is an abundance of light, and even if artificial, it is not harsh.

There is the use of quality materials throughout. Polished woods, glass,

steel, and perspex give a sense of contemporary luxury; the fittings and

fixtures have a sense of lightness, rather than solidity, reminiscent of

much contemporary inner-urban design. However, given that every shop

attempts to display its goods äs attractively äs possible in the hope of

selling more of its wares, what is it that this störe does which is more than

simple attractive design?

There is a strong visual continuity throughout the störe, due to

common elements in the fixtures and among the goods themselves,

a point which will be elaborated upon later. At the same time, how-

ever, the Store is divided into clearly differentiated thematic 'spaces',

encompassing such groupings of goods äs 'children's goods', 'water

Figure 1. Schematic layout of the störe: a guide only to its spatial layout; neither

comprehensive nor to scale. This sketch was prepared by the author.

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

492 Louise J. RavelU

sports\ 'country/equestrian sports', and so on. In addition, there are some

sections not directly related to merchandise at all, such äs a section

dedicated to sitting and watching a video on the history of the modern

Olympics, and a space at the bottom of the escalators for observing/

overlooking the pit. While all these spaces are visually distinct from each

other, they are seamlessly connected by an absence of physical barriers

and by clear directional paths between them. Having entered the Store by

the escalators, the visitor has the choice of going left or right, but is then

on a circular path which, whilst there are some diversionary possibilities

on the way, leaves little Option but to circumnavigate the Store äs a whole.1

The goods themselves contribute to both the luxury and the visual

integrity of the Store. While some items, such äs keyrings, might be in

a lower price bracket, nothing is cheap; relatively ordinary goods such

äs T-shirts and caps seil at prices far above those of more quotidian

examples of similar products elsewhere. Not insignificantly, price tags

note that purchase of the product helps support local athletes. Visually,

most of the products for sale are unified by the inclusion of the Inter-

national Olympic logo, the five interlocking rings, and/or the Sydney

Olympic logo, an abstract representation of an Olympic athlete and the

distinctive 'sails' of the Sydney Opera House. In addition, most of the

goods exhibit a certain consistency of color, tending towards the strong,

hyper-real primary colors of the Olympic rings. There are some excep-

tions to this, such äs the earthy greens and browns which predominate

in the outdoors/equestrian section; nevertheless, these are exceptions.

The Sydney Olympic mascots—'Syd' the Platypus, 'Millie' the Echidna,

and Olly' the Kookaburra—are ubiquitous, äs images on many of the

products and äs objects in their own right: cuddly toys and hard plastic

'dolls' of different sizes, brooches, keyrings, and so on.2

Another remarkable feature of the störe is the inclusion of sporting

and Olympic realia throughout, used with particular effect in the various

thematic sections. There are oars above the windcheaters, for example;

a recreation of swimming lanes and swimming Blocks amoiig tlic

swimming costumes; a section of floor which looks like an athletics

track in the shoe section; an actual recreation of the length of the sandpit

in the long Jump with the distances marked off on the floor, and even

a recreation of the Olympic winners' podium, where shoppers can stand

and have their photo taken. These are not ad-hoc inclusions, but form

part of a distinct and integrated visual identity of each of the separate

sections. See Figures 2 and 3 for some examples of these. Sometimes the

realia are so real that actual ex-Olympians are display' so to speak,

for the public to meet and interact with. For example, Murray Rose,

an Australian swimmer from the 1956 and 1960 Olympic Games,

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 493

Figure 2. 'Swimming blocks among the cossies (swimming costumes)': here, the floor

is marked out like the bottom ofa Swimmingpool and the starting blocks are above

the shoppers' heads; that is, the shopper is positioned 'in' the swimming pool. All

photos of the Olympic Store in Pitt Street, Sydney, are designed by Saunders

Design Pty Ltd, Sydney, and approved by SOCOG (the Sydney Organizing

Committeefor the Olympic Games), and taken by the au t hör.

'appeared exclusively' at the Olympic Store on Friday, 12 December 1997,

to help promote the 'exclusive first release' of the Murray Rose DNA Pin

Sets (Sydney Morning Herald, December 1997). A special space is reserved

for such activities, äs illustrated in Figure 4.

The inclusion of realia is one of several overtly intertextual devices

which mimic the display practices of museums, particularly contempo-

rary museums. The thematically differentiated sections represent an

imposition of order upon the content of the störe, similar to the ordering

and grouping of displays typical of some rrmseums where there is an

orientation to issues/experientially based displays, rather than the tax-

onomic classification of Information (Ravelli 1996). The störe also displays

a number of Olympic 'artefacts', for example, actual sporting equipment

used at particular Olympic Games, and it includes attractive displays of

texts, both one-line slogans displayed prominently throughout (äs detailed

further in the following section) and whole panels combining text and

image, äs is typical of museum practice. One panel, for example, profiles

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics (see Figure 5).

Another displays and labels the Olympic rings, and these two panels flank

a section reserved for the showing of a video on the history of modern

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

494 Louise J. Ravelli

Figure 3. 'Leng t h oft he longjump': note that the distance oft he longjump is marked out on

thefloor; on the left a recreatlon of the winners' podium can be glimpsed.

Olympics. This conjunction of devices is reminiscent of many orientations

to exhibitions familiär from museum practice.

This intertextual resonance with museum practice creates a cultural

cachet for the Store which it would otherwise not have. Museums, through

their processes of selection and display, give significance to otherwise

ordinary objects, and the Olympic Store also exploits this device. This

is not to suggest that the störe actually functions äs, or in place of,

a museum; it does not (although äs noted later, it can be clearly contrasted

with the Homebush Visitors' Centre, which does). Even a cursory glance

at what is represented would reveal a shallow treatment of Information.

It is the essence of a museum that is drawn upon in order to fulfil the aim

of selling merchandise and of selling something more than merchandise.

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 495

Figure 4. 'Athlete on display': an open spacefor interaction between guests and public.

Figure 5. Text panel profiling Baron Pierre de Coubertin.founder ofthe modern Olympics.

Thisflanks one side ofthe video area.

None of the features mentioned so far are sufficient on their own to

create the effect that the shop is more than it seems; it is not uncommon

for other shops, for example, to give exactly the same direction to spatial

flow (that is, an apparently open but actually clearly defined directional

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

496 Louise J. Ravelli

path, illustrated most famously perhaps by Ikea Stores). Yet while the

shared antecedents of museums and department Stores have been well

documented (Bennett 1995; Georgel 1994; Vergo 1989), it is nevertheless

the case that the Olympic Store combines a ränge of semiotic processes

which succeed in elevating it to a role above and beyond the mere sale

of merchandise. Indeed, it seems quite possible to go right through the störe

and not buy anything, and yet feel satisfied with this äs an 'experience'.

3. Reading the störe: Metafunctional perspectives and analyses

The störe would seem to be an example par excellence of Wernick's

'promotional culture' (1991). While ostensibly commercial in nature,

the störe is also much more than that, and äs Wernick (1991: 133)

notes, promotional culture includes 'promotional practices originally

commercial in function and Inspiration [which] have made their

strangely transformative appearance beyond the commercial zone'.

For him, promotional culture is 'an artificial semiosis: the industrial

manufacture of meaning and myth' (1991: 15). This artificial semiosis

consists of two key types of signs: promotional signs—all forms of

advertising, media events, the use of recognizable names and so on—and

commodity signs, 'which function ... both äs an object-to-be-sold and

äs the bearer of a promotional message' (1991: 16). As a whoie the störe

can be seen äs a sign within the broader promotional culture of the

Olympics, both specifically in Sydney and generally äs an international

phenomenon. At the same time, the störe itself is constructed of both

promotional signs (the Slogans, the special visitors, etc.) and commodity

signs (the goods for sale). In this way, the störe is a clear example of the

'infinitely recursive' discourse which characterizes promotional discourse

(Wernick 1991: 151).

How is it, then, that the störe instantiates this discourse? While

it is interesting to observe some of the design features already men-

tioned, this does not in itself explain how it is that the störe operates äs

a social semiotic, äs a coherent, meaningful text, situated within a par-

ticular social and cultural context. To begin to explain this störe äs a text,

we draw primarily on the work of Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) and

their social-semiotic analyses of images, and also the work of OToole

(1992) with a social-semiotic analysis of art and architecture. Both

approaches, while slightly different, share a foundation in Halliday's

social-semiotic approach to language. In particular, Halliday's notion

of the metafunctional potential of language is taken up by both Kress

and van Leeuwen and OToole in the analysis of other semiotics, and

it is that which will also be pursued here.

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond Shopping 497

According to Halliday, meaning (in language, but by inference in any

semiotic System) should be seen äs something much more than a simple

referential notion of content (Halliday 1973, 1978, 1994). He argues that

meaning encompasses at least three metafunctional Systems: the idea-

tional, the interpersonal, and the textual. Ideational meaning refers to

reasonably familiär notions of content in terms of representation; the

expression and construction of experience. Interpersonal meaning refers

to the roles and relationships constructed in and available through

semiosis, the sorts of interaction available to participants, and the expres-

sion of attitudes. Textual meaning refers to the organization and

prioritization of meanings made in other Systems, to the creation of text

through structure, coherence, foregrounding, and backgrounding.

In addition, Halliday emphasizes that the process of communication

is not one of simply 'conveying' pre-existing content between interlocuters,

but rather, it is one of actually constructing that content through the choices

made in the process of communication. Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) and

OToole (1992) explore these principles in semiotic Systems other than

language, and by extension, it is possible to consider the ideational,

interpersonal, and textual choices made in the Olympic Store, and their

significance for the shopper. Kress and van Leeuwen's descriptive

framework is further elaborated upon later, but we also make use of

O'Toole's rank-based description of architecture for a useful segmenta-

tion of the space. OToole suggests (1992: 85-87) that architectural 'texts'

are hierarchically structured elements of differing 'size': with building

äs the uppermost rank, followed by floor, then room, and then element

(that is, the components of a room). As with rank-based descriptions

of language (Halliday 1994), the same component may play a role at more

than one rank (thus in an imperative such äs Run\, the single word run

realizes functions at the rank of word, group, and clause). Similarly, the

störe äs a whole can be seen to be the 'building'; it is at this rank that it

functions in its entirety. This building consists of one 'floor', and within

this floor—whilst there are no dividing walls äs such—the thematically

grouped sections can be seen to be different 'rooms', composed of differ-

ent 'elements' (such äs goods for sale, shelves for display, realia on display,

and so on). A reading of each of the three metafunctions äs constructed

in and by the störe is presented in the following section.

3.1. The ideational metafunction

In ideational terms, the störe (just like a museum), selects and constructs

its own content, and there are several features of the content which are

particularly interesting. Firstly, the Olympics have been divided and

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

498 Louise J. Ravelli

represented in terms of key areas of sport; not necessarily specific events

äs such, although event groups such äs swimming and rowing are

represented, but more in terms of generic groupings: 'in the water', and

Outdoors', for example, or Outdoors and horsey'. It is the selection

and grouping of goods which realizes this taxonomy; in the 'water' section,

for example, there are not just swimming costumes and swimming goggles,

but bathrobes and splashjackets, beachtowels, sun protection, etc. In

other words, the selection and placement of the goods on sale is more

formative of the discursive space being constructed than the sport itself.

Thus, the very selection and placement of goods is one of the semiotic

modes in this space.3

Another interesting grouping in ideational terms is that of targeted

age; one section is specifically devoted to products for children, the

remainder, by default, is targeted at adults. Although i t should be added

that a double classification goes on (Bernstein 1996; Martin 1999a); the

children's section includes children's products across the ränge repre-

sented elsewhere in the störe, but the otherwise 'adult' sections usually

include the relevant products in children's sizes. Again, it is the selection

and placement of goods which constructs the relevance of the products.

It is yet another dimension of the expression of content that some

sections are not specifically related to a sport äs such, but might be related

to the history of the Games, to a representation of the Olympic spirit, or

to a 'behind the scenes' aspect of the Games, such äs the dressing room.

Through this coverage of the Olympics, the products look äs if they

belong; it is not so surprising to see products for two year-olds, who are

unlikely to even be observers of the Games let alone competitors, or to see

limited edition ceramics which have nothing to do with any actual sport.

But in context, and given the choices made about the representation

of content within this space, the products are naturalized; their place

within this scheme is not—from a compliant position—questioned.

3.2. The interpersonal metafunction

At the interpersonal level, what roles and relationships are available for

the shopper to take up? In shops, not unlike museums, it could be argued

that there is a continuum of roles available, ranging from the relatively

passive, where goods may be perused but not handled, to the relatively

active and open, where goods may be touched, turned over, and examined.

The ränge of options available may vary between Stores (contrast a jewelry

störe with an everyday clothing störe, for example) äs well äs within the

one störe (such äs a department störe where different types of goods are

available). At the Olympic Store, the active, open role predominates;

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 499

shoppers are generally free to browse and handle the goods. Some goods,

such äs fragile crystal and ceramics, are displayed in ways which make

them less easy to touch (placed up high, separated from other goods);

others, such äs small, easily 'lifted' goods, are displayed within glass cases.

Most importantly, however, there is a highly distinctive interpersonal

strategy that is deployed in the Olympic Store and marks it out from most

other shops. This is to invite the shopper to actually place themselves in the

Olympic games: to look at the sandpit, and imagine what it would be like

to jump that far; to stand on the winners' podium; to be in the swimming

pool; to identify with the Olympics, and at the very least, to be an observer

of something real and actual, something that belongs to the past, the

present, and the future—all projected äs shared—rather than something

vaguely imagined or beyond the experience of the ordinary person.

Shoppers are referred to äs 'spectators' on directional signs within the

störe, and are able through these devices to place themselves within the

very heart of the Games, and therefore not surprisingly, are likely to be

happy to take part of that experience home with them. One of the key

Slogans of the Sydney Olympics is 'Share the spirit', and that is exactly

what the störe enables shoppers to do.4

The creation of positive affect—happiness, enjoyment—is not irrele-

vant to the interpersonal meanings constructed in the störe. Positive affect

(Martin 1999b) is a strongly foregrounded feature across many Systems:

shoppers are likely to be greeted by someone offering a balloon; the staff

are extremely friendly and attempt to interact beyond the boundaries of

normal Service encounters; the mascots of Sydney 2000 (Syd, Millie, Olly),

projected äs friendly and accessible, are located at every possible buying

point; the colors are bright and hyper-real; the space is open; the displays

are interesting. This is an experience to be enjoyed.

3.3. The textual metafunction

Tn terms of textual meanings, we can examine the störe in terms of the

grouping or Isolation of content items, and the sequencing and

organization of space, äs a means of prioritizing the ideational and

interpersonal meanings, to create structure and coherence. As a multi-

modal text, the störe integrates a number of different semiotic codes, and

Kress and van Leeuwen (1996: 183) argue that such Integration may

be achieved through one of two overarching codes: 'the code of spatial

composition', operating in texts 'in which all elements are spatially

co-present', and 'rhythm, the code of temporal composition', operating

in texts 'which unfold over time'. By extension, they suggest (1996: 242)

that these frameworks can also be applied to three-dimensional visuals.

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

500 Louise J. Ravelli

On the one band, the störe is a static text, and all its semiotic elements are

spatially copresent. This is most obvious at the rank of individual 'rooms',

which can be taken in at a glance and viewed much like a picture. But

equally obviously, the experience of the störe is anything but static:

one has to move through the space in order to buy or to gaze. Even if one

Stands completely still, the störe can only be taken in by turning one's

head. As a text, it unfolds temporally. Thus, the störe is integrated via

a combination of the principles of spatial composition and of rhythm.

Spatial composition is realized by three interrelated Systems of

Information value, salience, and framing (Kress and van Leeuwen 1996:

183). In terms of Information value, various structuring principles, such

äs left and right, top and bottom, center and margin, create 'zones' which

are endowed with specific informational values. In horizontally structured

texts, the left-right zones produce Information values of 'given', where

that which is placed on the left

is presented äs something the viewer already knows, äs a familiär and agreed-upon

point of departure for the message. For something to be New means that it is

presented äs something which is not yet known, or perhaps not yet agreed upon

by the viewer, hence äs something to which the viewer must pay special attention.

(Kress and van Leeuwen 1996: 187)

In the störe, very little use is made of the horizontal axis äs a structuring

principle. At the rank of 'floor', there is a natural tendency to turn left

at the bottom of the escalators which lead in to the störe, and it is here that

the children's goods are displayed (thus marking 'youth' äs the 'natural'

or 'given' starting point), however, it is also possible to turn right, and

approach any of the displays from the right or the left. Nor do any of the

thematically differentiated displays—or 'rooms' in terms of O'Toole's

(1992) system—strongly favor the horizontal axis. What is clearly favored

äs a structuring principle—at the rank of 'room'—is the vertical axis,

where the zones of 'top' and 'bottom' are attributed with the informa-

tional values of 'ideal' and 'real', ßased on an analysis of page-based

magazine advertisements, where images of the product are typically

located towards the top of the page, and verbal text towards the bottom,

Kress and van Leeuwen note (1996: 193) that

... the upper section visualizes the 'promise of the product', the Status of glamour

it can bestow on its users, or the sensory fulfilment it will bring. The lower section

visualizes the product itself, providing more or less factual Information about the

product .... The upper section tends to make 'emotive' appeal and show us 'what

might be'; the lower section tends to be more informative and practical, showing

us 'what is'.

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond s h opp ing 501

Top' in the störe can be equated with visual displays placed up high,

well above eye level: here, Slogans about the Olympics (discussed again

in section 4) are visually salient, and promise the 'ideal' of the Inter-

national Olympic Games. Here also, and slightly lower, at eye level, are

salient displays of realia: the swimming blocks in the swimming section,

and the oars. The 'bottom' can be equated with items placed on the floor

and up to eye level: racks and shelves for the display of goods. This

would seem to accord neatly with Kress and van Leeuwen's description:

'what might be' (Ideals and Imagination) placed above, and 'what is'

(consumption) placed below. In addition, however, even lower, äs part

of the floor itself, are further realia: the distance markers for the long

jump, for instance, and the lanes of the swimming pool. However, the

realia here, äs opposed to that which is placed up high, seem to be literally

'real', and are perhaps one reason why these features are remarkable. They

are not the 'promise' of the Games, not the ideal which the Games

represent, but the actuality of the Games: the physical effort it requires

to jump that far.

The structuring principle of center and margin is used occasionally

in the störe äs a way of relating otherwise disparate spaces to each other.

For example, in Figure 4, the circular logo is made salient by its high,

ideal position, size, neutral coloring (in contrast to the bright, hyper-real

primary colors which are the unmarked realization for the goods), absence

of goods for sale, and by the mirror image of the neutral circle on the floor

underneath. All this creates a central focus, from which the racks of goods

for sale literally seem to radiate (or converge). As Kress and van Leeuwen

argue (1996: 206),

For something to be presented äs Centre means that it is presented äs the nucleus

of the Information on which all the other elements are in some sense subservient.

The Margins are these ancillary, dependent elements. In many cases the Margins

are identical or at least very similar to each other . . . .

In this instance, it is the athlete, both in the ideal form, äs embodied

by the logo up high, and in the real form, literally embodied by a person

at ground level, which is the nucleus of information: the background

against which the goods make sense. The various goods around this

space, at the margins (and also at the margins of other spaces on either

side) are thus given coherence.

The second compositional System, salience, is also important to the

Integration of meanings in the störe, and is realized in a number of ways:

through size, color, contrast, perspective, and so on. The störe seems

to use two competing patterns. Firstly, the bright colors, already men-

tioned and used for most of the goods and for many parts of the

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

502 Louise J. Ravelli

background displays, consistently draw attention to themselves. Every

item for sale—each T-shirt, each cap—is thereby salient, saying 'pick me,

pick me!' (Again, these are commodity signs in Wernick's sense.)

Secondly, more neutral colors, providing the background to the logos

placed up high (see Figure 4 again) and the color of the pathways between

spaces (see Figure 3), are made salient through contrast (with the bright

colors and busy spaces of elsewhere) and placement (up high and ideal,

or—literally—grounded and very real). The logos and connecting

pathways thus provide a kind of framing for the different 'rooms' within

the störe.

Framing may be strong or weak (Kress and van Leeuwen 1996: 214),

and is similar to O'Toole's notion of the 'degree of partition', which he

notes is 'an important aspect of the building äs text' (OToole 1992: 109).

Here, different sections are clearly segregated and differentiated, marking

off areas with specific content, and thus emphasizing the individuality

or uniqueness of the products (that is, the relevance of so many products).

At the same time, this framing is visual rather than physical and, äs the

pathways form clear connecting vectors between the different 'sections',

the relationship of the different sections to each other is seamless. The

counterbalancing of the two patterns of salience—the bright colors

of goods and displays versus the neutral framing devices—is repeated

rhythmically throughout the störe, both constructing ideationally separate

spaces and suggesting that all domains are equally important and need

to be 'visited'. In this way, shoppers or spectators are gently coerced into

following a particular direction, while being given apparently open

invitations to join in and become part of the experience. It is this com-

bination of potentially conflicting devices which positions the shopper

to compliantly move through and become part of what the störe offers,

and so to take away some essence of the Olympic spirit, if not an actual

product.

4. Reading the signs: Semiotic convergence on the road to ideology

What is this Olympic spirit' which shoppers are invited to share? The

störe presents a wealth of sensory experience; while the experience will not

be the same for every individual, neither does it present shoppers with

chaos. What consistencies of message, then, can be read in the störe?

Let us turn to the language displayed in this störe, privileging the text

äs a pointer to some of the key agendas manifested. There are a variety

of texts displayed throughout the störe, and one thematically coherent set

seems particularly important, namely those concerned with the Olympic

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 503

ideaF. The störe displays Slogans such äs the following (attributions are

äs noted on the original signs):

— The Olympic movement: its goal is to place sport at the Service of the

harmonious development of man.

— In the Olympic Oath, ask for only one thing: sporting loyalty.

— The Olympic Spirit is neither the property of one race nor of one

age.

— Sports do not build character: they reveal it. (Heywood Haie Brown)

— Olympism is a philosophy of life. It is not winning that counts, but

participating. (Monsignor Ethelbert Talbot)

— For each individual, sport is a source for inner improvement.

As noted previously, many of these texts are visually salient, being

placed up high, in the 'ideal' position, and prominent, and contrasting

in background to other elements of the störe. They are thus signalled

äs important components of the störe äs text. Examining them in their

own right, that is, äs instances of language äs a social semiotic, Martin's

(1999b) analysis of appraisal in texts is useful. Appraisal is part of

Halliday's interpersonal metafunction of language, and refers to the ways

in which lexis and grammar are used to construct and reveal attitudes

and evaluations of people and things. The Slogans deploy two co-existing

patterns of appraisal. On the one hand, several of the Slogans, such äs the

first and second in the above list, are tokens of judgement, appraising

the Olympic Games in terms of questions of ethics: the Olympic Games

are 'beyond reproach'; they are 'moral', 'ethical', 'law abiding'. Hence,

with the goal of placing 'sport at the Service of the harmonious

development of man', how could they be criticized? If the only thing

asked for is to be loyal to sport, how could this be criticized? Similarly, the

third slogan is also a token of judgement, this time of normality/capacity,

suggesting that the Olympics are universally significant and, through

this universality, thereby powerful. At the same time, other Slogans

reveal patterns of appraisal which demonstrate appreciation, particularly

in terms of valuation, indicating that the Games are 'worthwhile',

'significant'. In the third, fourth, and fifth Slogans, if sports 'reveal char-

acter', are 'a philosophy of life', and 'a source for inner improvement',

this explains why they are intrinsically important and fundamental,

'illuminating, enduring, lasting ...'. This pattern of valuation also appears

in the first slogan, with the 'harmonious' development of man: while

harmonious might more typically be used to appraise composition

in terms of questions of balance, here it is used to evaluate the entirety

of humanity's development äs a profound and worthwhile venture, due

in part at least to the contribution of the Olympic Games. Thus, the

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

504 Louise J. Ravelli

themes of harmony, unity, and loyalty in the Service of sport are projected

äs the cornerstones of the Olympic ideal.

Visually, the Olympic ideal is represented by the familiär symbol

of the five interlocking Olympic rings, representing the five so-called

'continents' of Europe, Africa, America, Asia, and Oceania. The Games

are universal and unifying, create harmony, engender loyalty to common

goals. But this unification in the interest of harmony represents a fabulous

elision of difference, also underscoring the textual themes. Not only are

the individual 'continents' represented äs being part of a larger, indivisible

whole, but the very naming and grouping of these so-called 'continents'

provides an extraordinary and problematic definition of boundaries,

erasing all but the mainstream voice in all cases. The Olympic ideal

requires the absence of heterogenous voices, and it is in this silencing

and erasure of difference that its ideological platform is exposed. The

homogenizing, Western, capitalist, and predominantly male enterprise

upon which the modern Olympics is based has been well documented from

a ränge of perspectives. Gultman (1994: 120) for example, explains that

'the modern Olympic Games began äs a European phenomenon and it has

always been necessary for non-Western peoples to participate in the games

on Western terms and that

while it is undeniably true that African and Asian athletes participate, they

compete on Western terms in Sports which either originated in or have taken their

modern forms from the West. The catalogue of Olympic Sports continues,

inexorably it seems, to lengthen, but traditional games and dances survive—at the

Olympics—äs a marginal folkloric phenomenon (1994: 138)

The IOC (International Olympic Committee) also remains a 'restricted

club' in terms of gender, not admitting women until 1981 (Gultman 1994:

132). Simson and Jennings (1992), äs quoted in Hoberman (1995), refer

to the members of the IOC äs the 'Lords of the Rings' for a number

of reasons:

... first, the sheer autonomy and freedom from surveillance enjoyed by many high-

ranking international functionaries inside and outside the IOC; second, how the

upper echelons of international organisations provide political and financial

opportunity and sanctuary to significant numbers of people who have com-

promised themselves in various ways back in their national communities; and

third, the long history of extreme right-wing personalities and attitudes within

the IOC. (Hoberman 1995: 6)

Such studies reveal that the modern Olympic Games is indeed above

all eise, an enterprise and that sport is placed at the Service of the IOC

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 505

members and their vision of exactly what it is that constitutes 'harmony'.

Nothing underscores the 'enterprise' metaphor more literally than the

störe itself: it is not there to give away freebies, or to offer a ränge

of officially sanctioned merchandise which is truly affordable so that

everyone might, indeed, be able to 'participate' in this event, an event

in which it is otherwise notoriously difficult for the ordinary person to take

part. Wilson (1996: 608; citing Whitson and Macintosh 1993) takes up

an extended sense of 'promotional culture', explaining that 'it works

on those not directly advantaged by persuading them that "we are part

of something important simply by living there"'.

The störe certainly makes some acknowledgment of the achieve-

ments of particular minorities; it demonstrates, in fact, that people from

marginalized backgrounds can also attain the Olympic ideal. However,

this tends to be in terms of Other bodies' (such äs very short ones, not the

type to normally excel at the Olympics) rather than Other races', and the

very need to assert the inclusion of Others' tends to underscore the point.

In Australia, the simultaneous pride over Cathy Freeman's athletic

success, and the furore surrounding her proud display of the Aboriginal

flag along with the Australian flag at the 1994 Commonwealth Games

in Canada, manifest the complex positioning resulting from this ideal.

As Wilson (1996: 614) describes, 'athletes compete äs representatives

of their nation and simultaneously participate äs exemplars of the supra-

national values of Olympism ...'. Freeman's display, and the complex

reactions to it, reveal a further tension between competing Symbols of

identity within Australia itself, with Arthur Tunstall, secretary-treasurer

of the Commonwealth Games Association since 1969, epitomizing a vain

attempt to suppress the marker of Aboriginal heritage in his instructions

to Freeman to not carry the Aboriginal Flag (see, for example, McGregor

[1998] for a description of these events from Freeman's point of view).

These observations are not to suggest that there is no room for Variation

in the reading of this störe äs text. As discussed by Cranny-Francis (1992),

and following Kress (1989), the textual reading position is 'the positioning

constructed for the reader at which all elements of the text make sense'

(Cranny-Francis 1992: 184), but different reading positions are possible.

A compliant reader accepts and negotiates this positioning unproblemat-

ically; a resistant reader rejects the text's positioning; a tactical reader

uses texts opportunistically, 'äs they can' (Cranny-Francis 1992: 183).

As Cranny-Francis emphasizes, the individual experience of any one

reader is unlikely to be singular, given the complexity of intertextual

relations in the negotiation of subjectivity.

While resistant or tactical readings of the störe are eminently pos-

sible, the compliant reading points to the convergence of the diiferent

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

506 Louise J. Ravelli

signs: to accept all that is offered äs natural and relevant, to identify with

the Games, to share and admire the Olympic ideal, to go äway happy,

preferably with a product under one's arm. The intertextual play with

museum practice highlights the cultural significance of the störe and the

event: the Olympic Games are not just a fortnight of kicking balls around,

throwing things, and splashing around in the water. The Olympics are

much more than that, and the Olympic Store is not just a place to buy

things with the Olympic logo plastered over them. That which is being

promoted in the störe is the 'true meaning' of the great Olympic ideal.

As Lord Killain is quoted äs saying on a sign above the winner's stand,

'It is only a small fraction who will stand on the Olympic Podium'. The

Olympics are a pinnacle of excellence, something to be greatly admired,

and hence, the values for which they stand, should also be admired.

Ironically, in this störe, anyone can stand on the podium, and thus

'participate' in this uplifting and important context, whether or not they

can afford the goods for sale, and whether or not they are ever likely

to make it on to an athletics track, let alone make it in record time.

It certainly seems almost sacrilegious to suggest anything negative

about the Olympics, but äs Barthes notes in his discussion of the power

of myth,

... myth consists in overturning culture into nature or, at least, the social, the

cultural, the ideological, the historical into the 'natural'. What is nothing but

a product of class division and its moral, cultural and aesthetic consequences

is presented (stated) äs being a 'matter of course' ... (Barthes 1977: 164)

Coubertin himself proclaimed Olympism 'beyond ideology' (Hoberman

1995: 1). Thus, it is self-evident in the störe that the Olympics and their

ideals are appropriate and important goals; to suggest otherwise is

to invite the reaction of 'but it's only sport'.

The constructedness of the position created in the Olympic Store

is revealed most clearly by a comparison with another Olympic site, the

Visitors' Centre at Homebush Bay, primary location for the Olympic

Games in 2000. Homebush Bay is some fifteen kilometers from the city

proper, and is in fact a disused industrial site and former abattoirs (see

also Wilson 1996). The Visitors' Centre is markedly different from the

störe. Firstly, it does not just mimic the practices of a museum, it is

a museum, at least with regard to some of the functions that a more

traditional museum fulfils. It has a reasonably formal and constrained

layout, again essentially circular, but with Information presented in

primarily passive forms, with invitations to observe and absorb, but not

interact. Opportunities to interact arise in a number of multiple choice

'games' located at Computer points throughout the center, but these are

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 507

constructed äs amusing diversions rather than äs serious central elements.

There is nothing for sale at all (a definite missed opportunity!) and the

center is organized around five themes: strongly framed and bounded

by physical Separation and distinct color coding. The themes are

development (the physical details of the site and its use during and after

the Games); transport (ways of getting to and from the site); environment

(how the development and maintenance of the site will be environmen-

tally sensitive); heritage (the natural, Indigenous, and European histories

of the site); and Sydney 2000 (the Games themselves). Throughout,

the foregrounded messages are those of the relevance and Utility of

the enterprise to the population äs a whole, before, during and after the

Games.5 It is the local population which is targeted, in a public relations

exercise intended to justify the use of the site, its construction and impact,

in economic, social, and environmental terms. Other themes, such äs the

Olympic ideal, are not absent, but neither do they constitute an organizing

principle for this center.

Thus, the meanings made in the Visitor's Centre, and the very

audience presumed, are in stark contrast to those of the störe. In the

störe, äs will have been obvious, it would seem to be the international

tourist who is the default target. I would suggest that many locals

would not even think of going into the störe, not perceiving its rele-

vance and/or rejecting its values outright. This is not to say that locals

are ignored or discouraged; indeed, special events—such äs meeting

famous athletes—are organized to attract locals with an appeal to

national and sporting identity. But the special efforts required to attract

the local suggest who the default audience is perceived to be. Notably,

similar Stores in suburban centers—where tourists are unlikely to visit—

have been singularly unsuccessful and have had to close down, though

smaller ranges of such goods have been distributed through department

and chain Stores. 1t seems that the design of the Olympic Store has

missed its mark: it has worked to construct the störe äs being not

relevant to local concerns; only locals who *buy' the international

appeal of the Olympics and the Olympic ideal and who also have

sufficient disposable income will consume its products.

5. Shopping äs text

It is not new to observe that the Olympics rest on the foundations

of a Western, homogenizing, capitalist enterprise. What is interesting

is to witness the manifestation of these ideologies in three-dimensional

space (and in addition to their manifestation in the opening and ciosing

ceremonies; see again Wilson 1996; Gultman 1994) and to consider how

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

508 Louise J. Ravelli

it is that such discourses can be constructed within and 4 by' a shop.

On what basis can it be argued that this shop is a text?

Through the work of Kress and van Leeuwen, and others already

mentioned, the nature and role of semiotic Systems other than language

has become more open to analysis. With their tools of semiotic critique,

we can begin to recognize the constructedness of other modes, and to

understand their role in the creation of discourse. And importantly, we

can begin to see the significance of multimodality in the production of

texts. According to Kress (1997a, 1997b), multimodality is an inherent

feature of any semiotic—writing, for example, has a physical, visual

reality which may be obvious, but which also has generally been ignored

in analyses of language. In addition, Kress points to the need to consider

multimodal texts, where different semiotics are co-present and share the

workload of making meaning.

The Olympic Store, äs a text, manifests an extension of this latter point:

for here it is not just the copresence of diiferent semiotic modes which

makes the shop a text. Its textuality arises from the interaction of the

different semiotic modes constitutive of the störe, that is, from the process

of intersemiosis. This term is introduced by Jakobsen (1971: 260) äs a way

of understanding processes of translation between verbal signs and non-

verbal sign Systems. Intersemiosis äs suggested here does not necessarily

imply translation äs such, but rather a coordination of semiosis across

different sign Systems (see also the development of Jakobsen's ideas

in ledema 1999 and in preparation). In relation to this, Eco (1977: 308),

referring to architecture, argues that the notion of 'architectural sign'

should be substituted for the notion of'architectural text', 'in which many

modes of sign production are simultaneously at work'; he further argues

(1977: 310), that 'the work of art is a system of Systems" (cf. Ravelli 1996),

and explains that one semiotic system may use another äs its expression

plane (1977: 55). In other words, a microsemiotic analysis of the individual

modalities—the language of the störe and the visual images and the

spatial layout and the use of color, etc.—would not constitute an analysis

of this store äs a text, because it is in the very interaction of the different

semiotic Systems that the textuality of the store arises. Features such

äs the selection and placement of the goods, the inclusion of realia, and

the seamless framing and Integration of different sections construct the

relevance of the goods äs consumable products. Color selection, and the

equation of goods with the broader themes of the international Olympic

ideal—constructed through language, selections of judgement and

appreciation, and visual devices such äs use of the vertical axis to con-

struct ideal/real values of Information—create the attractiveness and

appeal of the goods. The same devices—the selection and placement

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 509

of goods, the use of realia, of Slogans, of patterns of display and

organization also typical of museum practice—enable the störe to funct-

ion äs quasi-museum. The colors of the goods, the behavior of staff, and

the smiles of the toys result in a Saturation of positive affect and, combined

with the invitations to physically identify with the Games, to place oneself

in a moment or an instance of the Games, contribute to a positive

evaluation of both the goods for sale and the Games themselves, again,

at least for the compliant reader. Thus, äs Kress and van Leeuwen suggest

in their analysis of multimodal texts (1996: 183), the störe is more than

the sum of its parts: its various semiotics work together to produce

something altogether above and beyond any one of its constitutive

elements.

Again, however, the question of how to account for this arises.

By arguing that the störe is a multimodal text, a site which makes and

enables meanings, we are arguing that there must be some principle to its

organization äs a semiotic System. The intersemiosis between the different

modalities is not a random or chaotic relationship: the different Systems

co-pattern t o produce other meanings. And i t is this co-patterning which

is the key to understanding the störe or similar sites äs text. It is useful

at this point to return to some of Halliday's foundational work in social

semiotics, particularly his (1973) notion offoregrounding. While Halliday

was working primarily within language äs a semiotic System, he was faced

with a challenge similar to that faced by multimodal analysts. That is

to explain, in a semiotic that draws on a ränge of resources, how

a coherent text can be produced and why some features seem to be more

significant than others. Halliday suggested that the stylistic significance

of some linguistic features (in a particular text) derived from their

motivated prominence—or foregrounding—within that text. Foreground-

ing was 'first evolved by the Prague School linguists and developed grea-

tly by Mukarovsky' (Hasan 1989 [1985]: 94). Foregrounded features

stand out not because of statistical quirks, but because of their func-

tional relevance to a larger whole: 'a feature that is prominent will be

"foregrounded" only if it relates to the meaning of the text äs a whole'

(Halliday 1973: 112). A feature may be prominent either because it departs

from a 'norm', or because it attains or establishes a norm (1973: 113).

Further, the 'norm' is defined according to the perspective of the observer:

it may be a norm in relation to a pari of a text, a given text, or a sei of texts

(1973: 114). As noted, a foregrounded feature may or may not 'stand out'

in a statistical way, but it will be functionally motivated, and therefore

relevant.

Foregrounded features in the störe represent a point of contact between

the different modes, enabling the retention of their individual materiality,

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

510 Louise J. Ravelli

modes, and discourses (to borrow more of Kress's [1997a, 1997b] terms)

and the recognition of their different and similar responsibilities in the

composition oftext. In other words, each of the individual modalities (the

language, or the colors, or the spatial layout, etc.) is already a patterned

semiotic, and this individual specificity needs to be retained and recog-

nized. In addition, however, it is in the patterning of the patterns that

the störe äs text arises. It is in the way that selections from the different

modes co-pattern, that other meanings are created. As we have seen, such

patterning occurs reasonably congruently in the störe: all signs point in

the same direction, so to speak. But it would be equally possible, for

example, to exploit dissonance äs a principle of foregrounding.6

This notion of co-patterning of foregrounded elements is captured in

Hasan's discussion of second-order semiosis in verbal art (Hasan 1989

[1985]), and it is useful to use this äs an analogy for explaining what

is distinctive about intersemiosis in multimodal texts. (See also Martin

[1997] who uses this analogy to explore the semiotics of theatre. Royce

[1998] provides an alternative explanation of the co-patterning of different

modalities in terms of complementarity.)

In relation to verbal art, verbalization is the first point of contact with

the work; it draws on the meanings made in the relevant System—

language in this case—but these are first-order meanings. These patterns

are repatterned at the second stratum, that of symbolic articulation,

and so second-order meanings are ascribed. In Hasan's discussion, this

second-order semiosis is the key to language äs verbal art, and it is

'achieved through the consistency of foregrounding' (1989 [1985]: 99).

As she explains (1989 [1985]: 98): 'the first order meanings are like signs

or symbols, which in their turn, possess a meaning—a second order,

perhaps more general meaning'. Theme is the deepest and most general

level of meaning.

The analogy with multimodal text, then, is that a site like the Olympic

störe makes contact with a variety of semiotic Systems—language, image,

spatial control, lighting, etc.; it is from the co-patterning of the patterns

in these Systems that foregrounded patterns begin to emerge, leading

us to the stratum of symbolic articulation: the naturalization of the

products, the invitations to identify, the orientation to positive affect,

and so to the themes of the störe: the relevance and value of consumption

in relation to the Games (buying its products) and the relevance and

pertinence of the Olympic ideal (buying its story).

Hasan's work can easily lead to a narrow Interpretation of 'theme'

äs being dependent on the volition of the artist.7 Let us extend this

principle of patterning, then, to a broader one of all and any textual

practice, including that enacted by readers/shoppers. Thus we can focus

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 511

on a principle, namely, that it is the patterning of patterns which is at the

heart of intersemiosis, and that it is the process of intersemiosis which

characterizes a multimodal text, äs opposed to the mere copresence

of different modalities. Through attention to these aspects, we can begin

to see that which is the experience of the störe for the shopper/spectator/

visitor, and the experience is surely far beyond that provided by any one

of its constituent semiotics, and far beyond that of mere shopping.

To begin to understand how the störe is indeed enacted äs a text,

it would be necessary to observe shoppers in action: how are these spaces

used; what is ignored? How are the hierarchies of the various modalities

deployed and/or altered in interaction? This is an area which requires

further research, but casual observation of people's behavior in the störe

suggests three typical patterns of behavior or approaches to the Store.

Firstly, some people are primarily intent on shopping: they stop at dis-

plays of goods, browse through racks of clothes, pick items up to inspect

them, and possibly complete a purchase by going to a sales desk. Their

traversal of the störe is punctuated by the rhythm of the goods for sale.

Others, although definitely in the minority, seem intent on 'experiencing'

the störe. To say that they are there only to learn about the Games might

be overinflating the museum-like functions of the störe's displays, but

it does seem that these people are, at the very least, curious about

the Games. The rhythm of their traversal of the störe is punctuated

more by the displays of realia, stopping to watch the video, and so on,

than by the displays of goods. In between these two poles, the majority

of people seem to wander through the störe, making use of both these

Potentials: sometimes stopping to inspect goods, sometimes stopping

to attend to a display. We might suggest, then, that the störe constructs

different behavior potentials for visitors, and that their behavior can be

mapped äs waves of different types of activities, punctuated by different

rhythms.

Thus 'shopping' and 'visiting' are potentially parallel, seemingly inde-

pcndent activities, distinct 'waves' flowing through the störe. However,

by virtue of the nature of the störe, these activities are necessarily

connected, and formative of the same space; that is, even if intent

on shopping, one can't help but notice the background of the Games, and

vice versa. The two activities are also mutually constructive, that is, they

are overlapping waves. For instance, äs already discussed, the color and

design of the goods intersects with the constructed appeal of the Olympics,

hence the two senses of 'buying' which are operationalized in the Store:

consuming and believing. As noted, these suggestions are entirely

preliminary and require systematic observation of behavior to begin to

be verified äs well äs a much more developed description of behavior

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

512 Louise J. Ravelli

Potentials. 'Shopping', for instance, could be arranged on a continuum

of activities, from browsing, to inspecting goods, to completing a pur-

chase. Similarly, 'visiting', in the museum sense, is a continuum, from

casual looking to focus on a display, to possible 'evidence' of consumption

of the display äs text: recall of its content to a fellow visitor, perhaps.

Whatever the behavior potential enacted in the störe, this needs to be seen

äs somewhat different to, albeit interdependent with, a 'reading' of the

störe, äs discussed earlier. They are, perhaps, two sides of the same coin;

it is the process of enacting the störe äs text which enables a reading

to be produced.

6. Conclusion

This störe is a significant example of promotional culture at a time when

promotion of the 2000 Olympic Games reached Saturation point for

residents of Australia. It is itself a promotional sign within the artificial

semiosis surrounding the Games, and in turn contains and is constructed

by both promotional and commodity signs within the störe, realized

across a ränge of modalities. Browsing through the störe, we have

observed features such äs the type of goods for sale, its layout, and the

resonance of its display practices with that of museums. Yet the störe

produces an experience which is much more than that which can be

explained by stopping to look at any one of these features in Isolation.

To 'buy' the störe äs a text, äs a particular instance of promotion, we have

initiated a social-semiotic analysis of this space, inspired by the work of

Kress and van Leeuwen in particular—and also of O'Toole—in their

analyses of images and architecture, each building on Halliday's

foundational work on language äs a social semiotic. Thus, the störe has

been examined äs a metafunctionally complex text, producing particular

meanings in ideational, interpersonal, and textual terms, which resonate

with ongoing ideologies concerning the Olympic Games. These meanings

are produced by and across a ränge of semiotic modalities, and Halliday's

notion of foregrounding has been used to explain the störe äs an instance

of intersemiosis, a text which is more than the sum of its parts.

Having touched on foregrounding äs a means of explaining the inter-

semiotic Operation of a three-dimensional, multisensorial, multimodal

text, many questions remain to be explored. What has been described

here is a first-level analysis only, mapping out some of the distinctive

features of the modalities deployed, and highlighting a mainstream or

compliant reading of the text. Equally clearly, other readings need to be

accounted for: what might constitute a tactical reading of this space; what

resistant readings are possible? Perhaps one common resistant reading,

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyond shopping 513

esppecially for local residents, is to not enter the störe at all, recognizing—

eve-en before entering—its place within larger discursive frameworks within

whhich one does not want to participate.

l The need to account for this kind oftext in terms of its enactment, of the

behhavior potentials manifested in the störe, leads to a new avenue for

auadience/visitor research. In addition, the opportunity arises to undertake

sinmilar studies in agnate sites: exploring in one direction to other Olympic-

rehlated phenomena, äs already suggested; exploring the intertextual

paarallels with museums, for example; and exploring in other directions

to » other shopping experiences, such äs the 'lifestyle' Stores now common

in Western countries (see, for example, Morris 1993; Shields 1992).

Cldearly, more shopping, and more visiting, required . . . .

Ndotes

1. See also descriptions of directional pathways in museums, äs in Hooper-Greenhill, 1994.

2. As described on a merchandise label in the störe, the mascots are

Syd the Platypus: Tm named after Sydney—the site of the 2000 Olympic Games'

Millie the Echidna: The fact is my name represents the new Millenium—the year 2000'

Olly the Kookaburra: 'Why Olly? It Stands for the Olympic Games—Olly, Olly, Olly!'.

Needless to say, these mascots alone are more than worthy of analysis!

3. . I am grateful to David Mclnnes for stimulating and challenging discussions on this

point and on the article äs a whole. Thanks also to Rick ledema for useful references

and feedback, and to Carolyn MacLulich of the Australian Museum for providing the

original opportunity to speak on this subject.

4. . Lifestyle Stores—such äs Country Roadin Australia, or Next and Habitat in the UK, and

perhaps originally, the haute couture houses of France, or the grand jewelry houses such

äs Tiffany's— invite identification through a consistency of image and presentation;

purchase of one item promises the realization of the whole image. The Olympic Store,

however, carries this to a further extreme.

5. . The following are sample extracts from four different texts at the Hombush Bay Visitors'

Centre:

During the Games—the Stadium will seat 110,000 spectators for the Olympics and

Paralympics. During the Games it will host the opening and ciosing ceremonies and track

and field events. The Olympic Football Finals will also be held in the Stadium. After the

Games—the Stadium will be reconfigured to allow for seating for 80,000 spectators. It will

be used for major sporting and cultural events and represents a major legacy for

the Games.

The design of all venues and facilities developed by the Olympic Co-ordination Authority

will incorporate state of the art environmental features. The legacy passed on to the rest

of the world from the 2000 Games will be a new Standard of environmental performance

in design, construction and Operation, a showcase of Australian environmental design

and technology.

Wetlands, Homebush Bay, has some of the most important wetlands in Sydney. They are

made up of mangroves and saltmarshes which provide a habitat for waterbirds, fish and

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

514 Louise J. Ravelli

crabs. OCA's management plan for the wetlands ensures that they will be enhanced and

protected for future generations.

The restoration of Homebush Bay is the most ambitious development program ever

undertaken by the NSW Government. ... The area's long-term future offers a mix

of uses—sporting and recreational, exhibition and entertainment, residential and

commercial.

6. For example, the 'Kaboom' exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, in Sydney

in 1994, deliberately deployed confusing and disorienting elements to 'recreate the

disorientation of animation'. Their exhibition brochure stated that The rooms on Level l

are designed for fleeting, random and casual encounters: visitors are overwhelmed by

sights and sounds, and experience the intensity and craziness of animation "on the run"'.

7. Although this is not, in my opinion, in any way Hasan's own intention.

References

Barthes, Roland (1977). Image Music Text: Essays Selected and Translated by Stephen

Heath. Fontana Press: London.

Bennett, Tony (1995). The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London:

Routledge.

Bernstein, B. (1996). Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique.

London: Taylor and Francis.

Cranny-Francis, A. (1992). Engendered Fiction: Analysing Gender in the Production and

Reception of Texts. New South Wales University Press: Kensington.

Eco, Umberto (1977). A theory of Semiotics. London: Macmillan.

Georgel, C. (1994). The museum äs metaphor in nineteenth Century France. In Museum

Culture: Histories, Discourses, Spectacles, D. Sherman and I. Rogoff (eds.), 113-122.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gultman, A. (1994). Games and Empires: Modern Sports and Cultural Imperialism. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1973). Explorations in the Functions of Language. London: Edward

Arnold.

—(1978). Language äs Social Semiotic. London: Edward Arnold.

—(1994). Introduction to Functional Grammar (2nd edition). London: Edward Arnold.

Hasan, R. (1989 [1985]). Linguistics, Language and Verbal Art. Oxford University Press.

[Originally published by Deakin University Press.]

Hoberman, John (1995). Toward a theory of Olympic Internationalism. Journal of Sport

History 22 (1): 1-37.

Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean (ed.) (1994). The Educational Role of the Museum. London:

Routledge.

ledema, Rick (1999). Bureaucratic planning and Resemiotisation. In Proceedings of the 1997

European Systemic-Functional Workshop, Eija Ventola (ed.) 47-70. Amsterdam:

Benjamins.

—(in prep). Resemiotisation. Centre for Hospital Management and Information Systems;

University of New South Wales.

Jakobsen, R. (1971). Linguistic Aspects of Translation. In Selected Writings Vol II: Word

and Language. The Hague: Mouton, 260-265.

Kress, G. (1989 [1985]). Linguistic Processes in Socio-cultural Practice. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. [Originally published by Deakin University Press.]

Brought to you by | University of New South Wale

Authenticated | 129.94.106.67

Download Date | 10/22/13 11:57 PM

Beyon d sh opp mg 515

—(1997a). Visual and verbal modes of representation in electronically mediated commu-

nication: The potentials of new forms of text. In Page to Screen: laking literacy into t he

electronic erci, I. Snyder (ed.), 53-79. Sydney: Allen and Unwim.

— (1997b). Plenary address. Multi-modal workshop, University of Sydney, December.

Kress, G. and Hodge (1988). Social Semiotics, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kress, G. and van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design

London: Routledge.

Martin, Catherine (1997). Staging the reality principle: Systemic-functional linguistics and

the context of the theatre. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Macquarie University (Sydney).

Martin, J. R. (1999a). Mentoring semogenesis: Genre-based literacy revisited. In Pedagogy

and the Shaping of Consciousness: Linguistics and Social Processes, F. Christie (ed.),

123-155. London: Cassell.

— (1999b). Beyond exchange: Appraisal Systems in English. In Evaluation in Text: Authorial

Stance and the Construction of Discourse, S. Hunston and G. Thompson (eds.), 142-175.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martinec, Radan (1998). Cohesion in action. Semiotica 120-1/2: 161-180.

—(in press). Construction of Identity in Michael Jackson's Jam. Social Semiotics.

McGregor, Adrian (1998). Cathy Freeman: A Journey Just Begun. Sydney: Random House.

Mclnnes, David (1998). Attending to the instance: Towards a systemic based dynamic

and responsive analysis of composite performance text. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis,

Department of Semiotics, University of Sydney.

Morris, Meagham (1993). Things to do with shopping centres. In The Cultural Studies

Reader, S. During (ed.), 295-319. London: Routledge.

O'Toole, M. (1992). The Language of Displayed Art. London: Leicester University Press.

Ravelli, Louise J. (1996). Making language accessible: Successful text writing for museum

visitors. Linguistics and Education 8: 367-387.

Royce, T. (1998). Synergy on the page: Exploring intersemiotic complementarity in