Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Islam in Britain Review

Încărcat de

Brahim El FidaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Islam in Britain Review

Încărcat de

Brahim El FidaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Islam in Britain, 1558-1685 by Nabil Matar

Review by: Albert J. Loomie

Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring, 2000), pp.

105-106

Published by: The North American Conference on British Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4054001 .

Accessed: 22/06/2014 04:57

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The North American Conference on British Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.60 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 04:57:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Reviews of Books 105

Nabil Matar.Islam in Britain,1558-1685. New York:CambridgeUniversity Press. 1998.

Pp. xi, 226. $59.95. ISBN 0-521-62233-6.

Coveringthe period from the opening of the reign of ElizabethI to the deathof CharlesH,

Mataroffers a carefullyannotatednew assessmentof the steady impactof Islam on British

thoughtandits ultimateinfluenceon Britain'searlymodem culture.Historiansusuallyhave

some familiaritywith this topic in the narratives,selected for the collections of Richard

Hakluytor Samuel Purchas,which describethe fate of Englishmenin the Islamic world as

traders,diplomats,prisoners,or slaves. However,this monographhas a more sophisticated

purposeand far richeranecdotalsources,which are analyzedin five topical chapters.In the

first, the authorevaluates the relatively large numberof conversions that contemporaries

labeled as "turningTurk."Then follows a study of the varied characterizationsof these

"renegades"on the contemporarystage, or in the printedsermonsof influentialclergy. His

thirdand longest chapteris focused exclusively on Arabicinfluencesin Britain,such as the

study of the Qur'an(Matar'sspelling), or the new interestin Arabicin the universities.His

final two chapterstake up two unfamiliarreligious topics: the Christianbaptismof Turks

(far more frequent on the stage than in the real world) and the prospective role of the

"Saracens"in the eschatology of severallate seventeenth-centurytheologians.

Contemporariesbelieved there were a variety of reasons behind the conversion, or

"apostacy,"to Islam. A large number were capturedtravelers and sailors, who gained

freedom from slavery and then frequently prospered upon entering the service of an

influentialofficial. On the London stage, however, playwrightssuch as Kyd, Heywood, or

Dryden stressedtheir spiritualremorsein conscience. Some "renegades"who escaped and

returnedto Britainclaimedto be still Christianat heart,but sceptics, such as Laud,decided

to preparea new rite of reconciliationbefore theirfull acceptancein the church.The study

of the Qur'an had a weak start in England, since Alexander Ross, an Anglican cleric

responsible for the first English version in 1649, knew little Arabic and relied upon a

defective Frenchtranslation.For eighty-five years, in the absence of any reliable text, his

misleading lines led to many later misunderstandingsof Islamic religion. His book also

irritatedthe commonwealth'sleadership,who bannedRoss's "Alcoran,"since the preface

praisedthe "high"moralsof Islam, in comparisonto the "low"moralsof the Independent

regime.Latersome less controversialaspectsof Ottomanculturebecamepopularduringthe

Restorationperiod,such as coffee, or alchemy,or exotic novelties fromthe Levant.The elite

sought "priscasapientia" [ancientwisdom] said to have roots in the primitivetexts in the

care of Arabic sages.

While there were rareinstancesof a Muslim's conversionto English Protestantismover

this period,dramatistspreferredstill to createfictionalconversionson the stage. An Islamic

visitor found competing viewpoints, as Anglicans, Presbyterians,Quakers,and Puritans

promotedtheircreeds.Matarnotedthatthe news of a Turkishconvertto the Anglicanchurch

in November 1657 provokeda rivalryamongCromwell'sfollowersto gain a convertto their

views, which they reportedin January1659. Inpassing,the authornotesthe mistakennotions

among various denominationsabout Islam, for example that, since it did not share the

scriptureswith Jews andChristians,only argumentsfromreasonwould succeed.Even more

out of touch with reality was a "Restorationist"school, which held thata restorationof the

Jews to Palestine would lead to their victory in a battle with the Muslims and, after their

conversionto Christianity,they would declarethe region an English protestantkingdomof

Christ!It is quite clear in Matar'sconclusion that over this periodthe Islamic militaryand

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.60 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 04:57:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

106 Albion

religiouspower easily withstoodChristianimperialismand evangelizationand could

threaten"theshoresof Albion."Thepublicwasattimesfascinated andthenrepelledby the

Turksandonly afterthe treatyof Carlowitz(1699)didtheTurkishempirebecomemore

vulnerableto Europeanimperialism.Matarhaswrittena valuablemonograph ona complex

andrarelyresearched history,providinganimpressivebibliog-

areaof Englishintellectual

raphyfor the reader.His graspof Islamicculture,whichenableshim to pointout the

misunderstandingsof severalfamousseventeenth-century writers,also gives a modem

studentthe propercontextof a culturewhichin that earlierperiodwas not properly

discovered.

Fordham University ALBERT J. LOOMIE

RobertTittler.TheReformationand the Townsin England: Politics and Political Culture,

c. 1540-1640. New York: Oxford University Press. 1998. pp. xi, 395. $95.00. ISBN

0-19-820718-2.

Those expecting this importantstudy to offer an analysis of the religious history of towns

in the period, or indeed of the role of urbancommunitiesin religious change, should pay

close attentionto the wordingof its title and look elsewhere. This is a study of politics and

in particularthe transformationsin urbanpolitics wroughtby the effects of the Reformation,

which arenot seen primarilyin termsof religiouschanges (althoughthe eventualemergence

of Puritanor godly magistraciesis discussed),but of institutionalchangeandchangesin the

political culturethat had been associatedwith pre-Reformationreligious forms and which

were subsequently,in Tittler'sview, very largely secularized.These processes aretracedby

piecing together the histories of numerous middling and substantialprovincial towns:

London is discussed only infrequentlyand small towns are largely excluded.The subjectis

seen from the perspectiveof those seeking to govern such towns:this is neitherhistoryfrom

above based on the views and aims of centralgovernment(though it uses many central

records),nor historyfrom below, as it is little interestedin the experienceof ordinarytown

dwellers. However, both the state and the common people of the towns are important

referencepoints, since the core argumentof the book is thatthe Reformationforged a new

alliance between the state and the ruling groups in towns, of mutualbenefit, and that this

both requiredand enabled those rulersto establish a greaterdistance between themselves

andthe commonpeople thanhadbeen the normbeforethe Reformation.This book therefore

offers the most sustaineddefence for two decades of the notion of the growthof oligarchy

in early moderntowns, associatedwith the work of Clarkand Slack in the 1970s: indeed,in

many respects the book offers a detailed underwritingof many of the themes in their

provocative overview, English Towns in Transition (1976). Whereas Clark and Slack

stressed the socio-economic pressures towards oligarchy, Tittler is more inclined to a

political and culturalexplanationand his illustrationsof the trend are drawn from those

fields. Those acquaintedwith his many excellent essays andhis previousbook,Architecture

and Power (1991), will not be surprisedto learnthat the strongestmaterialdeployed here

relates to the mid-Tudorperiod and to such subjectsas the incorporationof towns and the

developmentof town halls and the otherappurtenancesof urbangovernment.While some

of this brings togetherhis earlierwork, other sections cover new ground,in particularthe

detailedreconstructionof how towns respondedto the threatsand opportunitiesbroughtby

the dissolutionof monasteriesandchantriesthroughenfeoffments,incorporations,andother

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.60 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 04:57:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Paradise Lost As An Islamic EpicDocument17 paginiParadise Lost As An Islamic EpicBrahim El FidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islam, Women, and Western ResponsesDocument22 paginiIslam, Women, and Western ResponsesBrahim El FidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Concise Companion To Feminist TheoryDocument5 paginiA Concise Companion To Feminist TheoryBrahim El FidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articles What Are Articles?: IndefiniteDocument4 paginiArticles What Are Articles?: IndefiniteBrahim El FidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of Unit 1Document2 paginiReview of Unit 1Brahim El FidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Student Committee Sma Al Abidin Bilingual Boarding School: I. BackgroundDocument5 paginiStudent Committee Sma Al Abidin Bilingual Boarding School: I. BackgroundAzizah Bilqis ArroyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- INDUSTRIAL PHD POSITION - Sensor Fusion Enabled Indoor PositioningDocument8 paginiINDUSTRIAL PHD POSITION - Sensor Fusion Enabled Indoor Positioningzeeshan ahmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sun God NikaDocument2 paginiSun God NikaElibom DnegelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Old Man and The SeaDocument10 paginiOld Man and The SeaXain RanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DOMESDocument23 paginiDOMESMukthesh ErukullaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Biophysical Techniques Series) Iain D. Campbell, Raymond A. Dwek-Biological Spectroscopy - Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company (1984)Document192 pagini(Biophysical Techniques Series) Iain D. Campbell, Raymond A. Dwek-Biological Spectroscopy - Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company (1984)BrunoRamosdeLima100% (1)

- Class 12 Unit-2 2022Document4 paginiClass 12 Unit-2 2022Shreya mauryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A List of 142 Adjectives To Learn For Success in The TOEFLDocument4 paginiA List of 142 Adjectives To Learn For Success in The TOEFLchintyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nugent 2010 Chapter 3Document13 paginiNugent 2010 Chapter 3Ingrid BobosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7540 Physics Question Paper 1 Jan 2011Document20 pagini7540 Physics Question Paper 1 Jan 2011abdulhadii0% (1)

- FBISE Grade 10 Biology Worksheet#1Document2 paginiFBISE Grade 10 Biology Worksheet#1Moaz AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3-CHAPTER-1 - Edited v1Document32 pagini3-CHAPTER-1 - Edited v1Michael Jaye RiblezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MJDF Mcqs - Mixed - PDFDocument19 paginiMJDF Mcqs - Mixed - PDFAyesha Awan0% (3)

- State Common Entrance Test Cell: 3001 Jamnalal Bajaj Institute of Management Studies, MumbaiDocument9 paginiState Common Entrance Test Cell: 3001 Jamnalal Bajaj Institute of Management Studies, MumbaiSalman AnwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- A-Z Survival Items Post SHTFDocument28 paginiA-Z Survival Items Post SHTFekott100% (1)

- Deictics and Stylistic Function in J.P. Clark-Bekederemo's PoetryDocument11 paginiDeictics and Stylistic Function in J.P. Clark-Bekederemo's Poetryym_hÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fractional Differential Equations: Bangti JinDocument377 paginiFractional Differential Equations: Bangti JinOmar GuzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper:Introduction To Economics and Finance: Functions of Economic SystemDocument10 paginiPaper:Introduction To Economics and Finance: Functions of Economic SystemQadirÎncă nu există evaluări

- (LaSalle Initiative) 0Document4 pagini(LaSalle Initiative) 0Ann DwyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- CFodrey CVDocument12 paginiCFodrey CVCrystal N FodreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Libel Arraignment Pre Trial TranscriptDocument13 paginiLibel Arraignment Pre Trial TranscriptAnne Laraga LuansingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bsa2105 FS2021 Vat Da22412Document7 paginiBsa2105 FS2021 Vat Da22412ela kikayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communication MethodDocument30 paginiCommunication MethodMisganaw GishenÎncă nu există evaluări

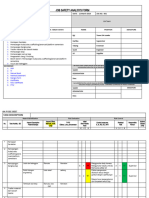

- JSA FormDocument4 paginiJSA Formfinjho839Încă nu există evaluări

- GSP AllDocument8 paginiGSP AllAleksandar DjordjevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA 2nd Sem SyllabusDocument6 paginiMBA 2nd Sem SyllabusMohammad Ameen Ul HaqÎncă nu există evaluări

- English 8 q3 w1 6 FinalDocument48 paginiEnglish 8 q3 w1 6 FinalJedidiah NavarreteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corporate Members List Iei Mysore Local CentreDocument296 paginiCorporate Members List Iei Mysore Local CentreNagarjun GowdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Regular and Irregular Verb List and Adjectives 1-Ix-2021Document11 paginiNew Regular and Irregular Verb List and Adjectives 1-Ix-2021MEDALITH ANEL HUACRE SICHAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Datasheet of STS 6000K H1 GCADocument1 paginăDatasheet of STS 6000K H1 GCAHome AutomatingÎncă nu există evaluări