Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Geopolitical Strategic Importance of Pakistan

Încărcat de

Syed Maaz Hassan0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

35 vizualizări4 paginiTitlu original

Geopolitical Strategic importance of Pakistan.docx

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

35 vizualizări4 paginiGeopolitical Strategic Importance of Pakistan

Încărcat de

Syed Maaz HassanDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 4

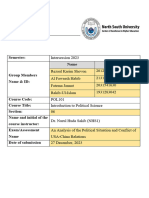

Geopolitical Strategic importance of Pakistan

The new Cold War (Munir Akram)

US Vice President Pence last week declared a new Cold War against China. America has now

decisively stepped into the Thucydides Trap — the Ancient Greek historian’s thesis that a

confrontation between an established and a rising power is almost always inevitable.

China was accused by Pence of multiple wrongs: unfair trade, technology theft, targeted

tariffs, interference in the US electoral process, a military buildup, militarisation of the South

China Sea islands (to keep the US out), ‘debt diplomacy’, anti-US propaganda and internal

oppression. Pence declared that the US “will not stand down” in opposing these alleged

Chinese policies.

Some believe that the US salvo was mainly designed to divert attention from the ongoing

investigation into Trump’s possible collusion with Russia in the 2016 presidential elections

and/or to mobilise votes for next month’s mid-term elections.

The confrontation between the US and China is

likely to escalate in words and deeds.

Yet, a deeper analysis indicates that Pence’s broad anti-China indictment reflects the

American ‘establishment’s’ considered policy. The speech was preceded by national

strategy papers describing China and Russia as America’s adversaries, trade tariffs and

investment restrictions, sanctions on Chinese military entities, renewed weapons sales to

Taiwan and expanding US Freedom of Navigation operations in the South China Sea.

Chinese efforts to build a so-called ‘win-win’ relationship through trade concessions and

cooperation on Korea and Afghanistan have clearly failed.

Chinese anger was visible during US State Secretary Pompeo’s Korea-related visit to

Beijing a few days ago, when Foreign Minister Wang Yi reportedly demanded that the US

stop its confrontational ‘behaviour’. The confrontation is likely to escalate in words and

deeds. It will become increasingly difficult for either side to ‘stand down’.

Apart from the raves of right-wing Americans, the Trump administration is unlikely to get

much joy from the open confrontation with China.

The trade tariffs Trump has imposed are unlikely to return many manufacturing jobs to

America since most Chinese goods will continue to be cheaper than their alternatives. US

consumers will pay higher prices. The China-located supply chains of many US

corporations will be disrupted, while China’s supply chains are mostly outside of the US.

Nor will technology restraints significantly dent China’s 2025 technology programme, since

it has already achieved considerable technological autonomy.

The Sino-US economic confrontation will have extensive consequences for the global

economy. The IMF estimates that the US and China may lose one per cent and two per

cent of growth respectively, while global growth would be trimmed by around half a

percentage point. There are fears of another global recession as other economies become

infected by the Sino-US trade war.

The prospects of the US “containing” China in the Indo-Pacific are also marginal. This is

China’s front yard. The US allies and friends in East Asia — even Japan, Australia and

South Korea — are economically intertwined with China and will be reluctant to confront it.

US Freedom of Navigation operations could lead to accidental conflict, as almost happened

recently. Short of war, the US cannot wrest the South China Sea islands from China. A

reckless US decision to discard the One-China policy could unleash a Chinese invasion of

Taiwan.

Despite US objections, and Western propaganda, China’s Belt and Road Initiative is

unlikely to be derailed. Developing countries will not forego the opportunity to build

infrastructure with Chinese financing. The ‘debt trap’ argument is misleading. Infrastructure

investment rarely offers commercial returns. But no country can industrialise without

adequate infrastructure. The US, with its parsimonious outlays on development cooperation,

cannot offer an alternative to China’s BRI.

The new Cold War will change the structures of global interaction and governance.

Cooperation among the major powers on global issues (non-proliferation, climate change,

terrorism) and in regions of tension (North Korea, Afghanistan, the Middle East) may be

frozen. China, Russia and the countries in the Eurasian ‘heartland’ will draw closer together.

Alternative trade, finance and development organisations will emerge to circumvent US

domination of existing institutions.

The strategic dynamics of South Asia could also be transformed. Although India is attracted

to America’s overtures for an anti-China alliance, it also wishes to avoid the ‘cost’ of

confrontation (Doklam) and to secure the benefits of trade and investment with China (the

‘Wuhan spirit’) as well as to maintain its arms supply relationship with Russia. The

escalating Sino-US confrontation will compress the time and space for India to get off the

fence and make a strategic choice between America and Russia-China.

Unlike India, Pakistan’s choice is clear. Its strategic partnership with China is critical for its

national security and socioeconomic development. This choice automatically implies a

strategic divergence with the US. The only question is whether Pakistan can maintain a

modicum of cooperation with the US despite the strategic divergence. Pakistan has some

room for manoeuvre so long as the US remains in Afghanistan, with or without a political

settlement there.

If India chooses to remain aloof from an alliance with US, and moves closer to China and

Russia, it could radically alter the calculus of the political and economic relationships in the

entire region. A Sino-Indian rapprochement would increase the prospects of Pakistan-India

normalisation and a compromise ‘solution’ for Kashmir. The visions of regional ‘connectivity’

would become reality. However, this scenario is highly unlikely until after the 2019 Indian

elections.

Although the new Cold War is wider and more complex than the old one, there is hope that

it may not be as prolonged. US public opinion will soon see that confrontation with China

(and Russia) is costly and counterproductive. A post-Trump Democratic administration may

well decide to opt for the ‘win-win’ relationship proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

View from abroad (Shada Islam)

China's ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) gets top international billing this weekend

as delegations from over 100 states, including 28 world leaders, gather in Beijing for a

summit showcasing the world’s first massive cross-continental connectivity master plan.

It’s going to be quite a party. And so it should. With billions of dollars of planned

investments ranging from ports in Pakistan and Sri Lanka to high-speed railways in Europe

and Africa to gas pipelines in Central Asia, the BRI is unparalleled in its scope, vision and

the amount of money involved.

And the multi-trillion dollar initiative to connect China with Europe, Asia and Africa is

gathering momentum as more and more countries sign up, old and new projects are

brought under the BRI umbrella and China begins to address some of the concerns voiced

by partner countries and critics.

Estimates about the amount of money involved in the plan vary enormously. Credit Suisse

Group AG says the BRI could funnel investments worth as much as $502 billion into 62

countries over five years. Other estimates put the BRI bill much higher.

The main point to remember is that the blueprint is an evolving one. Projects in New

Zealand, Britain and the Arctic are now within the BRI embrace. Others could come in later.

And while the money at stake is important for the countries engaging in the plan, the BRI is

about more than just investments.

Make no mistake: this is about fashioning a new world order, one where Washington no

longer calls the shots. And that’s exactly what is scaring many.

First mentioned by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, the BRI clearly articulates China’s

vision of its role in a changing and increasingly uncertain global order.

The timing is perfect. As US President Donald Trump continues to send mixed messages

on his international commitments and the strength of his global engagement, including on

trade and investments — and Europe grapples with Brexit and other crisis — the Chinese

initiative is securing additional traction and credibility.

Not surprisingly, Washington and Tokyo are not too pleased. Europe is interested but

cautious. Other countries are happy to engage and see how they can best benefit from the

plan.

So what do we know about the BRI?

First, it’s undoubtedly and unabashedly about geopolitics and geo-economics and China’s

self-confident repositioning of itself on the global stage.

While Washington and Tokyo — and some countries in Europe — may think such a

rejigging of the world could be dangerous, many other states aren’t too worried.

After all, “Brand America” isn’t too popular in many parts of the globe. And while China isn’t

always the gentlest of interlocutors, many countries are ready for a change.

Second, the BRI is only part of the story. Significantly, China’s Asian Infrastructure

Investment Bank (AIIB) is working in tandem with the BRI, to meet the world’s enormous

infrastructure investment needs. The $40bn Silk Road Fund is also an important tool to

finance infrastructure projects.

And even as the US withdraws from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the pan-Asian

(excluding China) trade pact, China and countries in the Association of Southeast Asian

Nations (Asean) are moving ahead with the Regional Comprehensive Economic

Partnership (RCEP) trade deal to boost trade within the region.

Importantly, President Xi, who made a strong stand for globalisation and trade liberalisation

at the Davos World Economic Forum in January this year, is expected to do so again at the

BRI Forum.

Third, there’s little doubt that the world needs to get better connected. Global infrastructure

needs are enormous. Better connectivity is crucial for trade, to attract investments and to

achieve some of the most crucial anti-poverty goals included in the Agenda 2030

sustainable development goals.

Fourth, BRI is not just about helping others. Search for new engines for domestic economic

growth are the main driver. China wants to boost growth in the western regions which lag

behind the well-developed east coast. Steel and cement are in oversupply and will be used

in the BRI projects. There will be job creation for thousands of Chinese workers but also

foreign nationals involved in the project.

Fifth, this is about learning by doing. Chinese academics admit that Beijing is using the BRI

to learn more about operating on the global stage. “China is a late-comer as a global

player,” according to a Chinese scholar. “We are in the process of learning how to act.”

While doing so, China is also changing. Slowly but surely, the focus is shifting to ensuring

that the BRI becomes more transparent, procurement rules become more rigorous and

projects fit in with the sustainable development goals, including environmental standards.

Significantly, as the initiative gains additional traction, China will have to conduct itself as a

“traditional” development partner, abandoning its “non-interference” policies for a stance

which is more concerned about the domestic affairs of its partner states, including issues

like governance and terrorism.

Beijing insists that the BRI will be inclusive and open to other countries, as well as

complement existing regional frameworks such as European Union, the African Union and

Asean.

Finally, for all the Western concerns that the BRI will allow China to steamroll its partners,

destroying everything and everyone in its path, the facts on the ground are very different.

In most countries, China is not the only actor in town. Most states still have access to US

and European funds, not to mention aid from Japan and Saudi Arabia.

It’s not a zero-sum game. Most governments taking part in the BRI will also keep their

contacts with Western governments, Japan and other international donors.

“We are not taking sides. The BRI will help us to fund our massive infrastructure needs. It’s

a great opportunity — but we’re also doing our homework,” a Southeast Asian diplomat told

this correspondent. “We will be in the lead. China knows and understands that.”

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The New Cold War by Munir AkramDocument3 paginiThe New Cold War by Munir AkramSaad BabarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transformation Without Changing The Meaning of A Sentence The "Not Old" Cold WarDocument3 paginiTransformation Without Changing The Meaning of A Sentence The "Not Old" Cold WarUsama QayyumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asian Juggernaut: The Rise of China, India, and JapanDe la EverandAsian Juggernaut: The Rise of China, India, and JapanEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)

- Blackwill USCHINARELATIONSDETERIORATE 2021Document7 paginiBlackwill USCHINARELATIONSDETERIORATE 2021lextpnÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Awkward Embrace: The United States and China in the 21st CenturyDe la EverandAn Awkward Embrace: The United States and China in the 21st CenturyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The China Syndrome: Grappling With An Uneasy RelationshipDe la EverandThe China Syndrome: Grappling With An Uneasy RelationshipÎncă nu există evaluări

- JWT Magazine May 2013Document112 paginiJWT Magazine May 2013Haleema SadiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- China Disadvantage - Harvard 2013Document34 paginiChina Disadvantage - Harvard 2013Brad MelocheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Has China Won?: The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy by Kishore Mahbubani: Summary by Fireside ReadsDe la EverandHas China Won?: The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy by Kishore Mahbubani: Summary by Fireside ReadsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary of Has China Won?: The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy by Kishore MahbubaniDe la EverandSummary of Has China Won?: The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy by Kishore MahbubaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- US-China Bifurcation World OrderDocument12 paginiUS-China Bifurcation World OrderCarlos Pariapaza VeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Analysis Behind United States of America and China Trade WarDocument8 paginiThe Analysis Behind United States of America and China Trade Wartiga milkitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catastrophic Timebomb Of Escalating US-China Confrontation: Who Is The Big Bully? Who Are The Hapless Victims?De la EverandCatastrophic Timebomb Of Escalating US-China Confrontation: Who Is The Big Bully? Who Are The Hapless Victims?Încă nu există evaluări

- The Sabotage: How the USA Planned to Undermine China's Belt and Road ProjectDe la EverandThe Sabotage: How the USA Planned to Undermine China's Belt and Road ProjectÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2ac From DemoDocument8 pagini2ac From DemoMatthew KimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 李昭逸 Lee Zhao Yi Charles 2002055404Document1 pagină李昭逸 Lee Zhao Yi Charles 2002055404Charles LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short of War How To Keep US Chinese Confrontation - FA Mar-APR 2021Document16 paginiShort of War How To Keep US Chinese Confrontation - FA Mar-APR 2021veroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asia Future Beyond US CompetitionDocument4 paginiAsia Future Beyond US CompetitionMaquacR7Încă nu există evaluări

- Summary of Elizabeth C. Economy's The World According to ChinaDe la EverandSummary of Elizabeth C. Economy's The World According to ChinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question 6 US China After 1991Document8 paginiQuestion 6 US China After 1991Kazi Naseef AminÎncă nu există evaluări

- In A Changing Geopolitical OrderDocument3 paginiIn A Changing Geopolitical OrderIbaad AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Propper ChinasPerspectiveCrisis 2020Document5 paginiPropper ChinasPerspectiveCrisis 2020lextpnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beyond Colossus or Collapse - Five Myths Driving American Debates About China - War On The RocksDocument12 paginiBeyond Colossus or Collapse - Five Myths Driving American Debates About China - War On The RockszoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2019-2020 Sept-Oct PF PRO CaseDocument6 pagini2019-2020 Sept-Oct PF PRO Casejohnantan hopkirkÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is No Grand Bargain With ChinaDocument7 paginiThere Is No Grand Bargain With ChinaAbdul basitÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is No Grand Bargain With ChinaDocument5 paginiThere Is No Grand Bargain With ChinaAnderson GodoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- US - ChinaDocument52 paginiUS - ChinaLong ThăngÎncă nu există evaluări

- US vs. ChinaDocument4 paginiUS vs. ChinaDhruv NaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- China's Perspective On The Crisis With The United StatesDocument5 paginiChina's Perspective On The Crisis With The United StatesLia LiloenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enter The Dragon: China's Growing Influence in The Middle East and North AfricaDocument24 paginiEnter The Dragon: China's Growing Influence in The Middle East and North AfricaHoover InstitutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- China Relations Core - Berkeley 2016Document269 paginiChina Relations Core - Berkeley 2016VanessaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Great Decoupling: Keith Johnson, Robbie GramerDocument15 paginiThe Great Decoupling: Keith Johnson, Robbie Gramerhương nguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is Biden's Foreign PolicyDocument15 paginiIs Biden's Foreign PolicyThavam RatnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- China Ascendant: Its Rise and ImplicationsDe la EverandChina Ascendant: Its Rise and ImplicationsEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)

- US China Competition and Corona VirusDocument3 paginiUS China Competition and Corona VirusAli HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- XuetongDocument6 paginiXuetongVasil V. HristovÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Inconvenient Truth: Aspirations Vs Realities of Coexistence Between "The West" and ChinaDocument5 paginiThe Inconvenient Truth: Aspirations Vs Realities of Coexistence Between "The West" and Chinarahul kadamÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEOG3016 Apr 19Document6 paginiGEOG3016 Apr 19joviwil966Încă nu există evaluări

- New Cold War: International RelationsDocument3 paginiNew Cold War: International RelationsRukhsar TariqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Trends 2020: Mapping the Global FutureDe la EverandGlobal Trends 2020: Mapping the Global FutureÎncă nu există evaluări

- China's Belt and Road Initiative and It's International Consequences.De la EverandChina's Belt and Road Initiative and It's International Consequences.Încă nu există evaluări

- To China With A Clear StrategyDocument3 paginiTo China With A Clear StrategyNikhil Kumar ChennuriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quarterly Essay 39 Power Shift: Australia's Future Between Washington and BeijingDe la EverandQuarterly Essay 39 Power Shift: Australia's Future Between Washington and BeijingÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Age of Slow Growth in China Foreign AffairsDocument11 paginiThe Age of Slow Growth in China Foreign Affairshenrique.silva.eiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Politics FileDocument41 paginiChinese Politics FileLincoln TeamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moldasbayeva Dilyara Response P1Document4 paginiMoldasbayeva Dilyara Response P1ДИЛЯРА МОЛДАСБАЕВАÎncă nu există evaluări

- China Presents The United States and Its PartnersDocument3 paginiChina Presents The United States and Its Partners王思远Încă nu există evaluări

- Nov Dec 22 Topic AnalysisDocument8 paginiNov Dec 22 Topic Analysisvsbkdcx6d8Încă nu există evaluări

- BRICS Without Mortar?Document5 paginiBRICS Without Mortar?irfan_oct26Încă nu există evaluări

- US and China Shifting SandsDocument5 paginiUS and China Shifting SandsphanvanquyetÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Game Between China and The United States Based On Trade in The Epidemic EraDocument8 paginiThe Game Between China and The United States Based On Trade in The Epidemic EraKwan Kwok AsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pol 101 Final DraftDocument24 paginiPol 101 Final DraftKim Hirai ChanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journalism Assignment 22Document4 paginiJournalism Assignment 22Safa Maryam KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Geopolitical RisksDocument6 pagini4 Geopolitical Risksguillermo garciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tài liệu nghiên cứu sinhDocument92 paginiTài liệu nghiên cứu sinhmanhtuan15aÎncă nu există evaluări

- US-CHINA Relations - Relationship Under DuressDocument7 paginiUS-CHINA Relations - Relationship Under DuressJie AckermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- US CHINA RelationsDocument3 paginiUS CHINA RelationsNgọc PhạmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peter Berger Reflections On The Sociology of Religion TodayDocument12 paginiPeter Berger Reflections On The Sociology of Religion TodayMaksim PlebejacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Silicon Valley Companies All Say They Want Black Engineers. So Why Don't They Hire Them?Document72 paginiSilicon Valley Companies All Say They Want Black Engineers. So Why Don't They Hire Them?Bill MillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language Choice in Note-Taking For C-E Consecutive InterpretingDocument11 paginiLanguage Choice in Note-Taking For C-E Consecutive InterpretingHasan Can BıyıkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 11 The Asia Pacific RegionDocument45 paginiChapter 11 The Asia Pacific RegionDonald PicaulyÎncă nu există evaluări

- US-ROK Alliance in The 21st Century - Denmark and FontaineDocument394 paginiUS-ROK Alliance in The 21st Century - Denmark and FontainesecdefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guanxi in Jeopardy Presentation 1Document22 paginiGuanxi in Jeopardy Presentation 1m__saleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islam in Taiwan: The Unlikely Story of An Important Global PartnershipDocument20 paginiIslam in Taiwan: The Unlikely Story of An Important Global PartnershipHoover InstitutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magic Weapons: China's Political Influence Activities Under Xi JinpingDocument57 paginiMagic Weapons: China's Political Influence Activities Under Xi JinpingJesu JesuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manajemen Kinerja Dalam Pemerintahan CinaDocument28 paginiManajemen Kinerja Dalam Pemerintahan CinaGinrey Shandy AlgamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 31 BlackmoresDocument2 pagini31 BlackmoresAilin MaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation +Global+Steel+Market+ +the+Present+and+the+FutureDocument33 paginiPresentation +Global+Steel+Market+ +the+Present+and+the+FuturemalevolentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huntington, S. (1991) - Democracy's Third WaveDocument23 paginiHuntington, S. (1991) - Democracy's Third WavePedro De Souza MeloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retail Supervisor (Chinese Books Department) - Popular Book Co. (M) Sdn. BHDDocument3 paginiRetail Supervisor (Chinese Books Department) - Popular Book Co. (M) Sdn. BHDAzim SengalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case 2 - Formosa Plastics Group (Report)Document4 paginiCase 2 - Formosa Plastics Group (Report)Azhar Joha100% (1)

- PHD THESIS Chang 2009Document399 paginiPHD THESIS Chang 2009Rachid BelaredjÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAL003Document585 paginiSAL003uliseÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Do I Contact The Service DeskDocument8 paginiHow Do I Contact The Service DeskBrianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educ 5324-Article Review Week 1 Rasim DamirovDocument3 paginiEduc 5324-Article Review Week 1 Rasim Damirovapi-3022455240% (1)

- Prince of Tears (涙王子 / Lei Wangzi)Document2 paginiPrince of Tears (涙王子 / Lei Wangzi)lawrenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- BusHisCoursesVol1Web (1 Importanttt PDFDocument474 paginiBusHisCoursesVol1Web (1 Importanttt PDFRishi KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence From China On The Value Relevance of Operating Income vs. Below-The-Line ItemsDocument26 paginiEvidence From China On The Value Relevance of Operating Income vs. Below-The-Line ItemsSyiera Fella'sÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0315富邦年報 - 英文.indd 1 2021/5/17 下午 02:54:09Document32 pagini0315富邦年報 - 英文.indd 1 2021/5/17 下午 02:54:09YudyChenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lawmakers Seek Accountability For Forced Organ Harvesting in ChinaDocument52 paginiLawmakers Seek Accountability For Forced Organ Harvesting in ChinaKeithStewartÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Building RevolutionDocument229 paginiA Building RevolutionAndrew Chan100% (1)

- JPM Asia Pacific Equity 2011-07-07 624664Document22 paginiJPM Asia Pacific Equity 2011-07-07 624664tommyphyuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 3 Lesson 3C Level 5Document13 paginiUnit 3 Lesson 3C Level 5Sheila Alejandra Jacinto JimenezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Chinese Diaspora - Chinese Studies - Oxford BibliographiesDocument3 paginiThe Chinese Diaspora - Chinese Studies - Oxford BibliographiesMelanieShiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Pursuit of A Small Utopia A Study of A Traditional Settlement Bi-Shan Village in Kinmen IslandDocument14 paginiThe Pursuit of A Small Utopia A Study of A Traditional Settlement Bi-Shan Village in Kinmen Islandvigo2144Încă nu există evaluări

- The Companys Chinese Pirates How The DutDocument30 paginiThe Companys Chinese Pirates How The Dutsebkk992344Încă nu există evaluări