Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Patient Satisfaction With Wait Times at An Emergency Ophthalmology On-Call Service

Încărcat de

myra umarTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Patient Satisfaction With Wait Times at An Emergency Ophthalmology On-Call Service

Încărcat de

myra umarDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Patient Satisfaction with Wait Times at an Emergency

Ophthalmology On-Call Service

Brian J. Chan, MD,* Joshua Barbosa, BHSc,*,† Prima Moinul, MD,* Nirojini Sivachandran, MD,*

Laura Donaldson, MD,* Lily Zhao, MD,* Sarah J. Mullen, MD,*

Christopher R. McLaughlin, MD,* Varun Chaudhary, MD, FRCSC*

ABSTRACT ●

Objective: To assess patient satisfaction with emergency ophthalmology care and determine the effect provision of anticipated

appointment wait time has on scores.

Design: Single-centre, randomized control trial.

Participants: Fifty patients triaged at the Hamilton Regional Eye Institute (HREI) from November 2015 to July 2016.

Methods: Fifty patients triaged for next-day appointments at the HREI were randomly assigned to receive standard-of-care

preappointment information or standard-of-care information in addition to an estimated appointment wait time. Patient satisfaction

with care was assessed postvisit using the modified Judgements of Hospital Quality Questionnaire (JHQQ). In determining how

informing patients of typical wait times influenced satisfaction, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed. As secondary study

outcomes, we sought to determine patient satisfaction with the intervention material using the Fisher exact test and the effect that

wait time, age, sex, education, mobility, and number of health care providers seen had on satisfaction scores using logistic

regression analysis.

Results: The median JHQQ response was “very good” (4/5) and between “very good” and “excellent” (4.5/5) in the intervention and

control arms, respectively. There was no difference in patient satisfaction between the cohorts (Mann-Whitney U ¼ 297.00, p ¼

0.964). Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that wait times influenced patient satisfaction (OR ¼ 0.919, 95% CI 0.864–

0.978, p ¼ 0.008). Of the intervention arm patients, 92.0% (N ¼ 23) found the preappointment information useful, whereas only

12.5% (N ¼ 3) of the control cohort patients noted the same (p o 0.001).

Conclusion: Provision of anticipated wait time information to patients in an emergency on-call ophthalmology clinic did not influence

satisfaction with care as captured by the JHQQ.

Performance-monitoring frameworks (PMFs) have metric may diverge from other PMF quality indicators

increasingly been adopted by the health service sector in because higher patient satisfaction scores have been

an attempt to improve efficacy and efficiency of care.1,2 In associated with both higher overall health care expendi-

Ontario, a prominent PMF is the quality-based procedures tures and increased mortality.8 Herein, we sought to assess

(QBP) system. Here, expert advisory panels develop the current state of patient satisfaction in an emergency

practice recommendations for a given procedure and ophthalmology on-call clinic setting using the modified

outline indicators to monitor quality improvements in a Judgements of Hospital Quality Questionnaire (JHQQ)

modified version of the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) struc- by Ware. In addition, the effect provision of anticipated

ture initially proposed by Kaplan and Norton.3 Reim- wait times had on satisfaction ratings was evaluated.

bursement has historically been tied to the quality

indicators in an attempt to drive systemwide

improvements. METHODS

Appropriate quality indicators and metrics that suffi- Study design and eligibility

ciently discriminate patient satisfaction are salient issues Patients presenting to the Hamilton Regional Eye

for the QBPs. The current QBPs for ophthalmic care Institute, Hamilton, Ont., for an emergency ophthalmol-

emphasize patient satisfaction and strive to place “the ogy on-call consultation from St. Joseph Hospital Emer-

patient/user at the center of the care delivery” and include gency Department and St. Joseph Hospital Urgent Care

“patients’ values, preferences and expressed needs in the Center in Hamilton between November 1, 2015, and July

care they receive.”4 Patient satisfaction, however, is a 31, 2016, were asked to participate in this study. Patients

complex outcome and is influenced by a plethora of were included in this study if they were 18 years or older at

factors. Uncertainty, cultural perceptions, and lack of the time of the appointment, proficient in English, and

perceived control over circumstances appear to modify both willing and able to give informed consent for study

satisfaction ratings.5–7 Moreover, the patient satisfaction participation. Potential study participants were excluded if

& 2017 Canadian Ophthalmological Society.

Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.08.002

ISSN 0008-4182/17

CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. ], NO. ], ] 2017 1

Patient satisfaction in emergency ophthalmology using JHQQ—Chan et al.

they had a mental or physical disability that precluded appointment had on perceived satisfaction as captured

accurate survey completion. If a patient presented with by survey responses, the Mann-Whitney U test was

poor vision and was willing to participate in the study, a performed. For all questions, the exact, 2-sided p-value

masked trained research assistant aided the patient in was calculated, with the standard alpha error of o0.05

completing study documentation. This study received considered significant.

ethics approval from the local institutional review board As a secondary study outcome, we sought to determine

(REB#0498) and adhered to the tenants of the Declara- what effect wait time to see a physician; patient age, sex,

tion of Helsinki. education, and mobility; and number of health care

Study participants were randomized to either a control providers seen at the appointment had on patient satisfac-

or intervention cohort. The control cohort received tion. The wait time satisfaction response was dichotomized

preappointment information that included the visit time as scores at or above the 50th percentile and scores below

and date, clinic location, and physician name if known at the 50th percentile. A score at or above the 50th percentile

the time. This was consistent with the Hamilton Regional corresponded to a survey response of “excellent.” To

Eye Institute’s standard of practice at the time. The preserve degrees of freedom, mobility was dichotomized

intervention cohort received identical preappointment as no help required or help required, and the number of

information with the addition of details regarding antici- health care providers was dichotomized as one provider

pated wait times, a descriptor of a typical patient encoun- seen or more than one provider seen. A forward logistic

ter at the clinic, and a suggested list of items patients could regression model was then performed; only those variables

bring with them to the appointment should they so that achieved statistical significance were included in the

choose. A copy of study intervention material is provided model. The odds ratios (ORs) of significant variables with

in Appendix 1. The intervention specifically addressed 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated and

uncertainty regarding wait times, explaining the reasons reported. The p-value of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-

behind potentially longer-than-expected wait times, and of-fit test was reported for the model. Study participants

introduced the concept of possible triaging among were asked to assess their satisfaction with the preappoint-

patients at the eye clinic. Randomization was performed ment information as either satisfied or not satisfied. The

in blocks of 4 with an allocation ratio of 1:1 between study Fisher exact test was used to compare responses between

cohorts. The ophthalmologists evaluating study partici- intervention and control cohorts.

pant were blinded to cohort assignment at the time of Analysis was performed on SPSS software (IBM, version

evaluation. 22.0). Post hoc, a histogram of patient wait time satisfac-

After the patient–physician encounter, study partici- tion scores by intervention, control, and all study partic-

pants were given a copy of the modified JHQQ. The ipants was generated on SPSS. If a given participant’s

questionnaire is available for reference in Appendix 2. The survey was missing a response to the primary research

JHQQ is a validated metric9 that assesses patient satisfac- question, the entire survey was excluded from analysis.

tion and has historically been applied to an English- However, if a response option other than the primary

speaking ophthalmic population.6 The JHQQ assesses endpoint was left blank, the survey was still included in

satisfaction on using a 5-point Likert response scale, with the primary analysis but was excluded in the analysis of the

response options consisting of “poor,” “fair,” “good,” “very missing domain.

good,” and “excellent” for most domains.

RESULTS

Statistical analysis From November 1, 2015, to July 31, 2016, 50 patients

Participant demographic information is summarized as consented to study participation. One of the 50 patients

means and standard deviations for continuous variables or failed to provide a survey response to the primary outcome

frequency with associated percentages for categorical and was subsequently removed from analysis. The study

measures. Survey responses were scored on a 5-point cohort consisted almost equally of male (46.9%) and

Likert scale, with 1 being the lowest or most disagreeable female (53.1%) participants. The mean age of study

score and 5 being the highest or most agreeable score. This participants was 54.4 ± 18.0 years. Total wait time to

was true of all questions except the final question, which see the doctor upon arrival at the eye clinic averaged 20.5

assessed patient satisfaction on a 3-point scale. We treated ± 23.6 minutes. Subsequent demographic information is

the survey scores as ordinal data. For ordinal data, the provided in Table 1. The survey response to question 2,

preferred measures of central tendency and dispersion are which reads, “Compared to your expectations, the wait

the median and interquartile range, respectively. Survey was poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent,” served as the

responses were reported using this convention. To assess dependent variable for the primary research question. The

the influence that informing the patient of typical wait median response was 4.00 for the intervention cohort and

times for an emergency on-call ophthalmology clinic 4.50 for the control cohort, meaning that the median

2 CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. ], NO. ], ] 2017

Patient satisfaction in emergency ophthalmology using JHQQ—Chan et al.

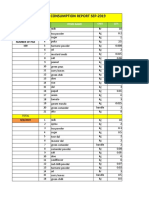

Table 1—Patient demographics

Variable Letter (N ¼ 25) Control (N ¼ 24) All (N ¼ 49)

Sex

Male, n (%) 12 (48.0) 11 (45.8) 23 (46.9)

Female, n (%) 13 (52.0) 13 (54.2) 26 (53.1)

First visit to clinic

Yes, n (%) 13 (52.0) 16 (66.7) 29 (59.2)

Education

Did not complete high school, n (%) 4 (16.0) 2 (8.3) 6 (12.2)

High school, n (%) 3 (12.0) 7 (29.2) 10 (20.4)

College or university, n (%) 15 (60.0) 11 (45.8) 26 (53.1)

PhD or masters, n (%) 0 (0.0) 2 (8.3) 2 (4.1)

Choose not to respond, n (%) 3 (12.0) 2 (8.3) 5 (10.2)

Severity of eye condition

Minor, n (%) 7 (28.0) 3 (12.5) 10 (20.4)

Moderate, n (%) 8 (32.0) 12 (50.0) 20 (40.8)

Serious, n (%) 10 (40.0) 8 (33.3) 18 (36.7)

Missing, n (%) 0 (0.0) 1 (4.2) 1 (2.0)

Assistance with mobility

A lot of help required, n (%) 1 (4.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (2.0)

Quite a bit of help required, n (%) 0 (0.0) 1 (4.2) 1 (2.0)

Some help required, n (%) 0 (0.0) 1 (4.2) 1 (2.0)

A little help required, n (%) 3 (12.0) 1 (4.2) 4 (8.2)

No help required, n (%) 21 (84.0) 21 (87.5) 42 (85.7)

Patient encounter with healthcare providers while at clinic visit

One doctor only, n (%) 16 (64.0) 16 (66.7) 32 (65.3)

2 or more doctors, n (%) 8 (32.0) 7 (29.2) 15 (30.6)

One doctor and a photographer, n (%) 1 (4.0) 1 (4.2) 2 (4.1)

Dilating eye drops

Not given during the appointment, n (%) 3 (12.0) 5 (20.8) 8 (16.3)

Drops given before seeing doctor, n (%) 4 (16.0) 4 (16.7) 8 (16.3)

Drops given after seeing doctor, n (%) 18 (72.0) 14 (58.3) 32 (65.3)

Missing, n (%) 0 (0.0) 1 (4.2) 1 (2.0)

Age (mean ± SD), years 58.2 ± 20.0 50.5 ± 15.2 54.4 ± 18.0

Wait time before being called into the clinic room (mean ± SD), minutes 14.7 ± 22.8 13.8 ± 16.3 14.2 ± 19.5

Wait time in clinic room waiting for the doctor (mean ± SD), minutes 8.1 ± 11.0 4.5 ± 4.8 6.3 ± 8.5

Total time waiting for the doctor (mean ± SD), minutes 22.8 ± 28.6 18.3 ± 18.1 20.5 ± 23.6

response was between “very good” and “excellent.” The DISCUSSION

25th and 75th percentiles for both intervention and Patient-centred care and individual autonomy are

control cohorts were 4.00 and 5.00, respectively. As mainstays of medical practice in Canada. Concerted efforts

captured in Figure 1, the response distribution was highly to involve patient feedback in clinical decision making

skewed for all respondents, but the distributions appeared

reflect these deeply held values. For this reason, ophthal-

relatively uniform across study arms. This is noteworthy

mology QBPs involve assessing patient satisfaction with

because the Mann-Whitney U test assumes a similar,

care.4 To date, there has been a paucity of studies

although not necessarily normal, distribution. There was

evaluating patient satisfaction with emergency ophthal-

no difference in satisfaction between those individuals who

mology care in a Canadian cohort. This study sought to

were given information on eye clinic wait times and

those who were not (Mann-Whitney U ¼ 297.00, address that knowledge gap.

p ¼ 0.964); neither were there any significant differences The median patient satisfaction score was “very good”

in satisfaction scores observed for all other survey (4/5) for the intervention cohort that received preappoint-

responses (see Table 2). ment approximate wait time information and “very good”

When evaluating the effect of age, sex, wait time, to “excellent” (4.5/5) for the control cohort. Thus, the

education, mobility, and number of health care providers provision of interventional information pertaining to

seen at appointment on patient wait time satisfaction, only anticipated wait times did not influence patient satisfac-

wait time to see the physician was statistically significant tion as captured by the JHQQ (Mann-Whitney U ¼

(OR ¼ 0.919, 95% CI 0.864–0.978, p ¼ 0.008). The 297.00, p ¼ 0.964). Regression analysis demonstrated that

Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test of the logistic physical wait times influenced patient satisfaction (OR ¼

regression was 0.089, suggesting that the model was a 0.919, 95% CI 0.864–0.978, p ¼ 0.008). For every

good fit. Of the intervention group participants, 92.0% additional minute spent waiting to see a doctor, the

(N ¼ 23) found the preappointment information regard- likelihood that a patient would give a satisfaction score

ing wait times and visit details useful, whereas only 12.5% in the top 50th percentile was 0.919. This means that a

(N ¼ 3) of the control cohort patients noted the same given patient was less likely to score his or her satisfaction

(p o 0.001). as “excellent” as time to see the doctor increased—a

CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. ], NO. ], ] 2017 3

Patient satisfaction in emergency ophthalmology using JHQQ—Chan et al.

Patient Wait-Time Satisfaction Intervention(N=25) Patient Wait -Time Satisfaction control (N=24)

Patient Wait-Time Satisfaction All (N=49)

Fig. 1 — Patient Satisfaction with Wait-Times.

finding consistent with previous research.5 Despite there problems.10 Patient satisfaction scores have been demon-

being no difference in patient satisfaction between the strated to correlate positively with all-cause mortality and

intervention and control cohorts, intervention patients higher health care expenditures.8 It is now known that, in

reported appreciating the anticipated wait time informa- part, these contradictory findings can be explained by the

tion. Of patients in the intervention group, 92.0% (23/25) fact that the experience a patient has at a given encounter

reported that information provided regarding wait times within a given health care system accounts for only a

and visit details was useful. Meanwhile, only 12.5% (3/24) fraction of variation in satisfaction scores. In a study of 21

of control patients reported the same (p o 0.001). The European Union countries, Bleich et al. found that

overall distributions of satisfaction scores were highly approximately 10% of all variability in patient satisfaction

skewed to the left (Fig. 1) in both control and intervention scores could be accounted for by patient encounter

cohorts, with 85.7% (n ¼ 42) of all study participants experience with the health care system.11 Meanwhile,

reporting a satisfaction score of either “very good” or other known factors explained some 17.5% of satisfaction

“excellent.” variability, whereas the majority of satisfaction variability

Thus, although patients reported that having knowledge can be attributed to as-yet-unknown determinants.11

of anticipated wait times was useful and that increases in Like many measures of patient satisfaction, the JHQQ

wait times decreased their satisfaction with care, neither uses a Likert scale. These metrics suffer from ceiling and

factor resulted in a statistically meaningful difference in floor effects, and their discriminatory ability has been

satisfaction scores between intervention and control called into question.12,13 The divergence between patient-

cohorts using the JHQQ. Apparent contradiction in reported relevance of anticipated wait time knowledge and

seemingly corollary proxies for patient satisfaction and actual wait times satisfaction suggests that the JHQQ scale

satisfaction with care itself is not a new phenomenon. itself had poor discriminatory ability in assessing patient

Donelan et al. reported high care satisfaction across experience with an on-call ophthalmology care system.

patients from 5 nations who described the health care This explanation is further corroborated by extensive left

systems of their individual countries as having significant skewing of survey scores in both study cohorts (see Fig. 1).

4 CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. ], NO. ], ] 2017

Patient satisfaction in emergency ophthalmology using JHQQ—Chan et al.

Table 2—Survey response

Question Letter Control Difference of Medians, Mann-Whitney U, p-value

Q1. Were you given choices, asked what’s important to you, and had your questions answered?

Poor, fair, good, very good, excellent

Median 5.00 4.00 203.00 0.643

25th percentile 4.00 3.50

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q2. Compared to your expectations, the wait was

Poor, fair, good, very good, excellent

Median 4.00 4.50 297.00 0.964

25th percentile 4.00 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q3. How clear and complete were explanations about tests, treatments?

Poor, fair, good, very good, excellent

Median 5.00 5.00 268.5 0.461

25th percentile 4.00 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q4. How well the doctor explained how to prepare for procedures/surgery

Poor, fair, good, very good, excellent

Median 5.00 5.00 239.5 1.00

25th percentile 4.00 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q5. Ability of the doctor to make you comfortable and reassure you

Poor, fair, good, very good, excellent

Median 5.00 5.00 288.5 0.876

25th percentile 4.00 4.25

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q6. Ability to diagnose problems, thoroughness of exam, skill in treating your conditions, knowledge

Poor, fair, good, very good, excellent

Median 5.00 5.00 277.00 0.660

25th percentile 4.00 4.25

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q7. The amount of time doctor spent with you

Poor, fair, good, very good, excellent

Median 5.00 5.00 292.5 0.851

25th percentile 4.00 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q8. Importance of being seen quickly

Don’t know, not at all important, not very important, somewhat important, very important

Median 5.00 5.00 246.50 0.237

25th percentile 4.00 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q9. Friendliness and concern of staff

Don’t know, not at all important, not very important, somewhat important, very important

Median 5.00 5.00 250.50 0.242

25th percentile 4.00 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q10. Importance of comfortable, pleasant clinic

Don’t know, not at all important, not very important, somewhat important, very important

Median 5.00 5.00 278.50 0.673

25th percentile 4.00 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q11. Importance of being seen by specialist or senior eye doctor

Don’t know, not at all important, not very important, somewhat important, very important

Median 5.00 5.00 255.00 0.250

25th percentile 4.50 4.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q12. Importance of spending a long time with the doctor

Don’t know, not at all important, not very important, somewhat important, very important

Median 4.00 4.00 241.00 0.305

25th percentile 4.00 3.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q13. There were some things about my visit that could have been better

Strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know

Median 4.00 4.00 239.50 0.545

25th percentile 2.00 3.00

75th percentile 4.00 4.00

Q14. The care I received at the hospital was so good I bragged to family and friends

Strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know

Median 1.00 2.00 185.50 0.065

25th percentile 1.00 1.00

75th percentile 2.00 3.00

Q15. I was very satisfied with the quality of care provided by the doctors

CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. ], NO. ], ] 2017 5

Patient satisfaction in emergency ophthalmology using JHQQ—Chan et al.

Table 2 (continued )

Question Letter Control Difference of Medians, Mann-Whitney U, p-value

Don’t know, strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree

Median 5.00 5.00 267.0 0.616

25th percentile 5.00 5.00

75th percentile 5.00 5.00

Q16. Were you completely satisfied, somewhat satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the hospital visit overall?*

Not at all satisfied, somewhat satisfied, completely satisfied

Median 3.00 3.00 163.50 0.858

25th percentile 3.00 3.00

75th percentile 3.00 3.00

*Graded on a scale of 3 instead of 5

The high satisfaction of study participants may be (n ¼ 42) of survey respondents scored their satisfaction

attributable to Bleich’s as-yet-unknown factors. Instead with wait times as “very good” or “excellent.” There was

of factors salient to the provision of care modulating no detected difference in satisfaction with care between

satisfaction scores, factors innate to the individual may be patients who received anticipated wait time information

responsible. and those who did not, despite there being a difference in

Study findings should also be interpreted in light of wait the proportion of patients who found the preappointment

time experienced by the population under investigation information useful. This may be explained, in part, by the

and sample size. Average wait time for study participants fact that the patient satisfaction metric used has limited

was 20.5 ± 23.6 minutes. Given that this wait time is discriminatory ability in our population. Although pre-

consistent with those of other services,14 wait times appointment information on estimated appointment wait

experienced by patients in the present study may be time had little effect on patient satisfaction with the

consistent with their preconceived notions of what con- ophthalmic visit, 92.0% of patients reported that the

stitutes a reasonable wait. The study sample size was 50. In information was useful, suggesting that the material may

light of the post hoc findings that the JHQQ had limited have some utility in improving the overall patient experi-

discriminatory ability in our ophthalmic population, a ence. Patient satisfaction with care has many determinants,

larger sample size is required to establish equivalence of and accurately assessing the construct is influenced by

satisfaction scores between study arms. numerous parameters, some of which are intrinsic to the

Future research exploring patient satisfaction in an individual. For this reason, using patient satisfaction

emergency ophthalmology on-call service clinic should measures in guiding health care system reform needs to

seek to evaluate the discriminatory ability of the scale be done with caution.

under investigation. Other disciplines have found that

scales with a lower number of response categories have

poorer validity, reliability, and discrimination power than APPENDIX

scales with more response categories.15 A wider scale may, Supplementary data

in part, overcome the poor discriminatory ability of the Supplementary data associated with this article can be

JHQQ scale in this investigation. As patient satisfaction found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

metrics increasingly play a relevant role in the provision of jcjo.2017.08.002.

care and systemic changes on an administrative level, it is

paramount that outcome indicators reflect the intended

construct they are designed to measure in a valid and

discriminatory manner. REFERENCES

1. Topol EJ, Califf RM. Scorecard cardiovascular medicine. Its impact

Limitations and future directions. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:65-70.

2. Tu JV, Schull MJ, Ferris LE, et al. Problems for clinical judgement:

This was a single-centre study at an academic ophthal- surviving in the report card era. CMAJ. 2001;164:1709-12.

mology clinic. Results may not be generalizable to non- 3. Kaplan RS, Norton DP. The balanced scorecard: translating strategy

teaching sites. into action. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1996: , 21-41.

4. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Quality-based procedures

clinical handbook for cataract day surgery. Toronto: Queen’s Printer

CONCLUSIONS for Ontario; 2015.

5. McMullen M, Netland PA. Wait time as a driver of overall patient

No study to date has sought to determine the extent to satisfaction in an ophthalmology clinic. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:

which providing a Canadian cohort of patients with 1655-60.

6. Billing K, Newland H, Selva D. Improving patient satisfaction

expected wait times a priori influences emergency oph- through information provision. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;35:

thalmology care satisfaction. Our study found that 85.7% 439-47.

6 CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. ], NO. ], ] 2017

Patient satisfaction in emergency ophthalmology using JHQQ—Chan et al.

7. Leung V, Vanek J, Braga-Mele R, et al. Role of patient choice in 15. Preston CC, Colman AM. Optimal number of response categories

influencing wait time for cataract surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. in rating scales: reliability, validity, discrimination power, and

2013;48:240-5. respondent preferences. Acta Psychol. 2000;104:1-15.

8. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction:

a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization,

expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:

405-11.

9. Ware JE, Hays RD. Methods for measuring patient satisfaction with Footnotes and Disclosure:

specific medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:393-402.

10. Donelan K, Blendon RJ, Schoen C, et al. The cost of health system The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any

change: public discontent in five nations. Health Aff. 1999;18: materials discussed in this article.This article includes online-only

206-16. material. Appendices 1 and 2 can be found on the CJO web site

11. Bleich SN, Ozaltin E, Murray C. How does satisfaction with the at http://pubs.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/cjo/cjo.html. They are linked to this

health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health article in the online contents of the xxx 20xx issue.

Organ. 2009;87:271-8.

12. Moret L, Nguyen JM, Pillet N, et al. Improvement of psychometric From the *Hamilton Regional Eye Institute, Research Unit,

properties of a scale measuring inpatient satisfaction with care: a Division of Ophthalmology, Department of Surgery, McMaster

better response rate and a reduction of the ceiling effect BMC Health University, Hamilton, Ont; †Wayne State School of Medicine,

Serv Res. 2007;7:197. Detroit, MI.

13. Howorka K, Pumprla J, Schlusche C, et al. Dealing with ceiling

baseline treatment satisfaction level in patients with diabetes under Originally received Feb. 20, 2017. Final revision Jul. 8, 2017.

flexible, functional insulin treatment: assessment of improvements in Accepted Aug. 8, 2017.

treatment satisfaction with a new insulin analogue. Qual Life Res.

2000;9:915-30. Correspondence to Joshua Barbosa, BHSc, Division of Oph-

14. Downey LV, Zun LS, Burke T. Comparison of Canadian triage thalmology, Department of Surgery, Hamilton Regional Eye

acuity scale to Australian emergency mental health scale triage for Institute, 2757 King Street East, Hamilton, Ont. L8G 5E4;

psychiatric patients. Int Emerg Nurs. 2015;23:138-43. joshuawilliambarbosa@gmail.com

CAN J OPHTHALMOL — VOL. ], NO. ], ] 2017 7

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- UK Tax SystemDocument13 paginiUK Tax SystemMuhammad Sajid Saeed100% (1)

- Basics of Fire SprinklerDocument21 paginiBasics of Fire SprinklerLeo_1982Încă nu există evaluări

- CXC - Past - Paper - 2022 Solutions PDFDocument17 paginiCXC - Past - Paper - 2022 Solutions PDFDarren Fraser100% (1)

- Dungeon World ConversionDocument5 paginiDungeon World ConversionJosephLouisNadeauÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cqi ProjectDocument5 paginiCqi Projectapi-307103979Încă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Quality 1Document11 paginiNursing Care Quality 1Nora100% (1)

- Method StatementDocument29 paginiMethod StatementZakwan Hisyam100% (1)

- Summary of Purposes and ObjectivesDocument19 paginiSummary of Purposes and Objectivesrodolfo opido100% (1)

- Pe 3 Syllabus - GymnasticsDocument7 paginiPe 3 Syllabus - GymnasticsLOUISE DOROTHY PARAISO100% (1)

- Sample - Critical Review of ArticleDocument11 paginiSample - Critical Review of Articleacademicproffwritter100% (1)

- (Bruce Hannon, Matthias Ruth) Dynamic Modeling of (BookFi) PDFDocument284 pagini(Bruce Hannon, Matthias Ruth) Dynamic Modeling of (BookFi) PDFmyra umar100% (1)

- General Chemistry 2 Quarter 4 - Week 4 Module 4: PH of Buffer SolutionsDocument12 paginiGeneral Chemistry 2 Quarter 4 - Week 4 Module 4: PH of Buffer SolutionsHazel EncarnacionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Satisfaction Survey at A Tertiary Care Speciality HospitalDocument5 paginiPatient Satisfaction Survey at A Tertiary Care Speciality HospitalJasneep0% (1)

- 3 Compiled Research PDFDocument31 pagini3 Compiled Research PDFChristine ObligadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Satisfaction SurveyDocument113 paginiPatient Satisfaction SurveyCherry Mae L. Villanueva100% (1)

- Journal Article Critique Nursing 665Document5 paginiJournal Article Critique Nursing 665api-214213767Încă nu există evaluări

- Biografi Sayuti MelikDocument8 paginiBiografi Sayuti MelikDwima NafishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Satisfaction While Enrolled in Clinical TrialsDocument13 paginiPatient Satisfaction While Enrolled in Clinical TrialsAlessandra BendoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 Patient-Satisfaction-From-Medical-Service-Provided-By-University-Outpatient-Clinic-Taif-University-Saudi-ArabiaDocument8 pagini2015 Patient-Satisfaction-From-Medical-Service-Provided-By-University-Outpatient-Clinic-Taif-University-Saudi-Arabiaapouakone apouakoneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 437 FullDocument6 pagini437 Fullvishalkamra_kamraÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmp7B69 TMPDocument7 paginitmp7B69 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient's Satisfaction With Perioperative Care: Development, Validation, and Application of A QuestionnaireDocument8 paginiPatient's Satisfaction With Perioperative Care: Development, Validation, and Application of A QuestionnaireIda KatarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Satisfaction Level of Patients Visiting Outpatient Department in A Tertiary Care Hospital of Delhi - A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument6 paginiSatisfaction Level of Patients Visiting Outpatient Department in A Tertiary Care Hospital of Delhi - A Cross-Sectional StudyAdvanced Research PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Experience of Inpatient Care and Services ReceivedDocument9 paginiPatient Experience of Inpatient Care and Services ReceivedsanjayÎncă nu există evaluări

- ResearchDocument6 paginiResearchKrishoban BaskaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Assessment of Patients Satisfaction With ServicDocument14 paginiAn Assessment of Patients Satisfaction With Servicsubhan takildarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient's Satisfaction With Perioperative Care: Development, Validation, and Application of A QuestionnaireDocument8 paginiPatient's Satisfaction With Perioperative Care: Development, Validation, and Application of A QuestionnaireHugo GutiérrezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 281 FullDocument9 pagini281 FullReRe DomilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Satisfaction Reporting - A Cohort Study Comparing Reporting of Patient Satisfaction Pre-And Post-Discharge From HospitalDocument7 paginiPatient Satisfaction Reporting - A Cohort Study Comparing Reporting of Patient Satisfaction Pre-And Post-Discharge From HospitalnrlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pharmacy 07 00128 v2 PDFDocument8 paginiPharmacy 07 00128 v2 PDFMr XÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quality Improvement and Revalidation Two Goals, SDocument4 paginiQuality Improvement and Revalidation Two Goals, SRENAULTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Professional Med J Q 2013 20 6 973 980Document8 paginiProfessional Med J Q 2013 20 6 973 980Vikram AripakaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parental Satisfaction of Child 'S Perioperative CareDocument8 paginiParental Satisfaction of Child 'S Perioperative CareHasriana BudimanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manuscript Revision 10.15.20Document22 paginiManuscript Revision 10.15.20John SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Karly BallDocument2 paginiKarly Balleva agustinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1553725021000982 MainDocument7 pagini1 s2.0 S1553725021000982 MainNovia khasanahÎncă nu există evaluări

- En CuestaDocument6 paginiEn CuestaToño VargasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Systematic Oral Care in Critically Ill PatientsDocument7 paginiEffects of Systematic Oral Care in Critically Ill PatientsCarlene AlincastreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient-Completed Screening Instrument For Functional Disability in The ElderlyDocument8 paginiPatient-Completed Screening Instrument For Functional Disability in The ElderlyJorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kuesionerkepuasan Persalinan MackeyDocument10 paginiKuesionerkepuasan Persalinan MackeyHasiati HamadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- B.inggris Kelompok 8Document6 paginiB.inggris Kelompok 8lia aryanti sholekahÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief Instrument To Measure Patients' Overall Satisfaction With Primary Care PhysiciansDocument6 paginiA Brief Instrument To Measure Patients' Overall Satisfaction With Primary Care Physiciansمالك مناصرةÎncă nu există evaluări

- Haspel 2014Document7 paginiHaspel 2014FOURAT OUERGHEMMIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phillips Postanaesthetic 2013Document11 paginiPhillips Postanaesthetic 2013Alex PiecesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appraisal of Evidence WorksheetsDocument10 paginiAppraisal of Evidence Worksheetsapi-577634408Încă nu există evaluări

- 10 11648 J SJCM 20150405 16Document8 pagini10 11648 J SJCM 20150405 16djianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mayo Clinic DMAICDocument5 paginiMayo Clinic DMAICSAIFUL AZHAR MASRIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Services: Development of A Questionnaire Patients' SatisfactionDocument5 paginiServices: Development of A Questionnaire Patients' SatisfactionViki TamÎncă nu există evaluări

- CQI by CommitteeDocument6 paginiCQI by CommitteeJhOy XiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perception and Use of The Results of Patient Satisfaction Surveys by Care Providers in A French Teaching HospitalDocument6 paginiPerception and Use of The Results of Patient Satisfaction Surveys by Care Providers in A French Teaching HospitalSagor AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- RetrieveDocument7 paginiRetrieveGestión Clínica SeguraÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIH Public AccessDocument11 paginiNIH Public AccessDian WrwÎncă nu există evaluări

- KUESIONER JOURNAL - Assessment Patient SatisfactionDocument6 paginiKUESIONER JOURNAL - Assessment Patient Satisfactionmufidah mawaddahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articulos Sobre CaphsDocument11 paginiArticulos Sobre CaphsJulioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Online ISSN 2278-8808, SJIF 2021 7.380, Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal, Jan-Feb, 2022, Vol-9/69Document17 paginiOnline ISSN 2278-8808, SJIF 2021 7.380, Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal, Jan-Feb, 2022, Vol-9/69Anonymous CwJeBCAXpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Other (CD, NR, NA)Document6 paginiOther (CD, NR, NA)Carl JungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palliative Care Phase - Inter-Rater Reliability and AcceptabilityDocument26 paginiPalliative Care Phase - Inter-Rater Reliability and Acceptabilityuwuwu yeahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doctor PT RelationshipDocument7 paginiDoctor PT RelationshipSanjeevan DeodharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rapid Response Team Whitepaper With Intro UPDATEDDocument24 paginiRapid Response Team Whitepaper With Intro UPDATEDHari Mas KuncoroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quality of Post-Operative Nursing Care Among Patients Subjected To Cardiac SurgeryDocument3 paginiQuality of Post-Operative Nursing Care Among Patients Subjected To Cardiac Surgeryjilan Amer abdullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dieta Os AspectosDocument8 paginiDieta Os AspectosGiulia GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 6 Assignment: Creating MeasuresDocument7 paginiWeek 6 Assignment: Creating MeasuresDrÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study To Assess The Patient's Satisfaction On Nursing Care in Emergency DepartmentDocument3 paginiA Study To Assess The Patient's Satisfaction On Nursing Care in Emergency DepartmentIOSRjournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Patient Satisfaction and Factors AffDocument6 paginiEvaluation of Patient Satisfaction and Factors Affsopha seyhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Patient Expectations at Emergency Department TriageDocument15 paginiManaging Patient Expectations at Emergency Department TriageHans GrobakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cunningham - Perceptions of Outcomes of Orthodontic Treatment in Adolescent Patients - A Qualitative StudyDocument21 paginiCunningham - Perceptions of Outcomes of Orthodontic Treatment in Adolescent Patients - A Qualitative StudyMilton david Rios serratoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Patients Satisfaction by Services Rendered in Medical OPD's of District Headquaters, FaisalabadDocument12 paginiAssessment of Patients Satisfaction by Services Rendered in Medical OPD's of District Headquaters, FaisalabadAbdul HafeezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Maximally Efficient and Optimally Effective Emergency Department: One Good Thing A DayDe la EverandThe Maximally Efficient and Optimally Effective Emergency Department: One Good Thing A DayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 8Document7 paginiJurnal 8myra umarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 2Document6 paginiJurnal 2myra umarÎncă nu există evaluări

- JurnalDocument9 paginiJurnalmyra umarÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Bruce Hannon, Matthias Ruth) Dynamic Modeling of (BookFi)Document8 pagini(Bruce Hannon, Matthias Ruth) Dynamic Modeling of (BookFi)myra umarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Registration Statement (For Single Proprietor)Document2 paginiRegistration Statement (For Single Proprietor)Sherwin SalanayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scope: Procter and GambleDocument30 paginiScope: Procter and GambleIrshad AhamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- 'Bubble Kid' Success Puts Gene Therapy Back On TrackDocument5 pagini'Bubble Kid' Success Puts Gene Therapy Back On TrackAbby Grey Lopez100% (1)

- Big 9 Master SoalDocument6 paginiBig 9 Master Soallilik masrukhahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classification of Speech ActDocument1 paginăClassification of Speech ActDarwin SawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaDocument32 paginiA Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaSonu PradhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parche CRP 65 - Ficha Técnica - en InglesDocument2 paginiParche CRP 65 - Ficha Técnica - en IngleserwinvillarÎncă nu există evaluări

- India Wine ReportDocument19 paginiIndia Wine ReportRajat KatiyarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Processing NC II - SAGDocument4 paginiFood Processing NC II - SAGNylmazdahr Sañeud DammahomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nitric AcidDocument7 paginiNitric AcidKuldeep BhattÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2 and 3 ImmunologyDocument16 paginiChapter 2 and 3 ImmunologyRevathyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Far Eastern University - Manila Income Taxation TAX1101 Fringe Benefit TaxDocument10 paginiFar Eastern University - Manila Income Taxation TAX1101 Fringe Benefit TaxRyan Christian BalanquitÎncă nu există evaluări

- REV Description Appr'D CHK'D Prep'D: Tolerances (Unless Otherwise Stated) - (In)Document2 paginiREV Description Appr'D CHK'D Prep'D: Tolerances (Unless Otherwise Stated) - (In)Bacano CapoeiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engineering Project ListDocument25 paginiEngineering Project ListSyed ShaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Document4 paginiDaily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Manjit RawatÎncă nu există evaluări

- PPR Soft Copy Ayurvedic OkDocument168 paginiPPR Soft Copy Ayurvedic OkKetan KathaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chemical Reaction Engineering-II - R2015 - 10-04-2018Document2 paginiChemical Reaction Engineering-II - R2015 - 10-04-201818135A0806 MAKKUVA BHAVYAÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEOPLE V JAURIGUE - Art 14 Aggravating CircumstancesDocument2 paginiPEOPLE V JAURIGUE - Art 14 Aggravating CircumstancesLady Diana TiangcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intershield803 MDSDocument4 paginiIntershield803 MDSSahanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Records in Family PracticeDocument22 paginiMedical Records in Family PracticenurfadillahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report in Per Dev CorrectedDocument34 paginiReport in Per Dev CorrectedJosh lyan RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epo-Fix Plus: High-Performance Epoxy Chemical AnchorDocument3 paginiEpo-Fix Plus: High-Performance Epoxy Chemical Anchormilivoj ilibasicÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALL102-Walker Shirley-Unemployed at Last-The Monkeys Mask and The Poetics of Excision-Pp72-85Document15 paginiALL102-Walker Shirley-Unemployed at Last-The Monkeys Mask and The Poetics of Excision-Pp72-85PÎncă nu există evaluări