Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

King Philips War Teacher Materials

Încărcat de

api-458708621Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

King Philips War Teacher Materials

Încărcat de

api-458708621Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

King Philip’s War Lesson Plan

Central Historical Question

What caused King Philip’s War?

Materials:

• King Philip’s War PowerPoint

• Copies of Documents A-C

• Copies of Guiding Questions

Note: The version of Document A that’s included in the Student Materials file is heavily

modified for length and clarity. We have worked to keep the document representative of

the original version. However, you may wish to visit the Original Documents file if you

would prefer not to use a heavily modified version.

Plan of Instruction:

1. Use PowerPoint to introduce lesson:

a. Slide 1: Title Slide. Today we’re going to learn about a war that broke out

between Native Americans and English colonists in New England in 1675.

b. Slide 2: Map of New England. Point out New England on a map.

c. Slide 3: Indigenous Nations of the Region. Long before the English settled

present-day New England, Algonquian peoples lived in the region. One of these

Algonquian nations was the Wampanoag. Their society was built around family

relations. Both men and women could serve as their leader, called a sachem,

who governed their nation along with councilors, elders, and lower sachems.

In the early 17th century, the Wampanoag lived in present-day Rhode Island and

southeastern Massachusetts. Wampanoags came into contact with European

merchants at this time.

d. Slide 4: English Settlers in New England. When the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, the

Wampanoag taught the Pilgrims how to fish and grow crops. Epidemics from

diseases brought by Europeans, land seizures by settlers, and fighting against

the colonists caused the deaths of many Native Americans in New England.

From 1600 to 1675, the region's Native American population decreased from

140,000 to 10,000. During the same time period, the English population grew to

50,000.

After a war between English colonists and the Pequot in 1636-1637, New

England was free of major armed conflict for about forty years. In 1645, New

STANFORD HISTORY EDUCATION GROUP sheg.stanford.edu

England Puritans launched a campaign to convert the Native Americans to

Christianity. About 2,000 Native Americans lived in “praying towns,” where

missionaries pressured them to give up their cultures and become Christians.

e. Slide 5: Sachem Metacomet. Metacomet (whom the English called King Philip)

was the sachem of the Pokanoket, a tribe of the Wampanoag nation. In 1675, he

forged a military alliance with about two-thirds of the region's Native Americans.

f. Slide 6: King Philip’s War. In June 1675, Metacomet led an attack on an English

settlement in Swansea, Massachusetts. Over the next year, Native Americans

attacked more than half of New England’s towns and destroyed twelve out of

ninety, killing five percent of New England’s colonists. Native American

casualties in New England were higher; perhaps 40 percent were killed by

colonists or forced to flee as a result of colonial attacks. The English called this

conflict King Philip’s War. In August 1676, colonial forces killed Metacomet, then

mutilated his body and publicly displayed it. Shortly after, Native American

defenses collapsed. Colonists sold many surviving Native American men into

slavery in the West Indies and enslaved many women and children in New

England. Colonists sent a smaller number of Native Americans to praying towns.

g. Slide 7: Central Historical Question. Today you’re going to read three historical

documents to answer the question: What caused King Philip’s War?

2. Warm-up: Have students answer the following three questions based on the lecture:

a. What happened to New England’s Native American population in the years

leading up to 1675?

b. What were the results of the war between Native Americans and English

settlers in 1675?

c. Based on what you learned, what do you think caused the war?

3. Elicit student answers to the Warm-up.

4. Hand out Document A and the Guiding Questions. Have students answer sourcing

questions 1 and 2, then read the document and answer the rest of the questions for

Document A.

5. Review student answers and discuss.

Document A notes:

STANFORD HISTORY EDUCATION GROUP sheg.stanford.edu

• Students may be skeptical about the reliability of this source. Metacomet

didn't write it; a colonist did. This is important to bear in mind. At the same

time, the author provides a detailed account of his conversation with

Metacomet, and he includes Metacomet’s criticisms of the colonists. He

appears to be faithfully reporting Metacomet’s grievances. We should also

consider Easton’s intent in making this account – to avoid war – and how this

could have influenced what he included.

• Students should note that this meeting was preceded by the execution of

three Wampanoag men, which angered the Wampanoag. English authorities

organized this meeting in order to try to prevent Native American retaliation

on the colonies after the executions.

6. Hand out Document B. Have students answer Questions 1-3, then read the

document and answer the rest of the questions for Document B.

7. Review student answers to the Guiding Questions and discuss:

Document B notes:

• Students may note that King Philip’s War was very costly to the English.

Edward Randolph summarizes the losses in the final paragraph of the

document. Students may reason that the English wanted to create this report

to help prevent future losses.

• Students should note that the report refers to the Native Americans as “rude”

and “heathen.” Students may also cite the passage “Upward of 3,000 Indian

men women and children destroyed, who if well managed would have been

very serviceable to the English.” This indicates Edward Randolph considered

the deaths of Native Americans a loss because he wanted the English to use

the Native Americans to serve English interests.

• Students need to source the document. Randolph was neither a colonist nor a

Wampanoag. He was an English official. Students should consider how this

may limit his perspective and understanding of what caused King Philip’s

War.

o Randolph presents what he says were the causes of the war according

to the colony of Massachusetts. We should consider the fact that

Randolph was not a colonist himself.

o At the same time, we know that the English government commissioned

Randolph to learn the cause of the war, so he may have tried to tell the

truth.

STANFORD HISTORY EDUCATION GROUP sheg.stanford.edu

8. Hand out Document C. Have students answer Questions 1-3, then read the

document and answer the remaining questions for Document C.

9. Review student answers to the Guiding Questions and discuss:

Document C notes:

• Students should reason that as an advocate for Native Americans rights,

Apess likely gave this speech in order to present a Native American

perspective on the causes of King Philip’s War.

• Students should consider the possible strengths and limitations of this

document as an account of the causes of King Philip’s War. On the one hand,

Apess delivered this speech long after the war and therefore was not present

during the escalation of the conflict between the Native Americans and

settlers. On the other hand, Apess was a renowned author, who may have

carefully studied the history of the conflict. Additionally, Apess’s speech

represents the historical interpretation of someone who advocated for Native

American rights.

10. Have students answer the final question in pairs. Discuss.

Sources

Document A

John Easton, “A Relation of the Indian War” in A Narrative of the Causes Which Led to

Philip’s Indian War (Albany: J. Munsell, 1858), 5–15. Retrieved from

https://openlibrary.org/books/OL6532032M/A_narrative_of_the_causes_which_led_to_

Philip's_Indian_war_of_1675_and_1676

Document B

Albert B. Hart, ed., American History Told by Contemporaries. Vol. 1, 458-60. (New

York, 1897). Retrieved from

http://books.google.com/books?id=cxs8AAAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Document C

William Apess, “Eulogy on King Philip as Pronounced at the Odeon, in Federal Street,

Boston,” 1836. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/eulogyonkingphil00apes

.

STANFORD HISTORY EDUCATION GROUP sheg.stanford.edu

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Abraham in Arms: War and Gender in Colonial New EnglandDe la EverandAbraham in Arms: War and Gender in Colonial New EnglandEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (2)

- 06 - STD Assignment King Philips WarDocument2 pagini06 - STD Assignment King Philips Warapi-272525201Încă nu există evaluări

- American History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Alan Brinkley Solutions ManualDocument7 paginiAmerican History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Alan Brinkley Solutions Manualmrsshelbyjacksoncoebmdywrg100% (16)

- The Story of American History For Elementary SchoolsDe la EverandThe Story of American History For Elementary SchoolsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dwnload Full American History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Alan Brinkley Solutions Manual PDFDocument36 paginiDwnload Full American History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Alan Brinkley Solutions Manual PDFholleyfeldkamp100% (15)

- Historical Background: King Philip's WarDocument5 paginiHistorical Background: King Philip's WarFfff DdddÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lincoln's Spymaster: Thomas Haines Dudley and the Liverpool NetworkDe la EverandLincoln's Spymaster: Thomas Haines Dudley and the Liverpool NetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strangers Within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British EmpireDe la EverandStrangers Within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British EmpireEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Solution Manual For American History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Brinkley 0073513296 9780073513294Document36 paginiSolution Manual For American History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Brinkley 0073513296 9780073513294nancymorganpmkqfojagx100% (24)

- Solution Manual For American History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Brinkley 0073513296 9780073513294Document7 paginiSolution Manual For American History Connecting With The Past 15th Edition Brinkley 0073513296 9780073513294anthonyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solution Manual For American History Connecting With The Past 15Th Edition Brinkley 0073513296 9780073513294 Full Chapter PDFDocument28 paginiSolution Manual For American History Connecting With The Past 15Th Edition Brinkley 0073513296 9780073513294 Full Chapter PDFmargaret.hammers950100% (12)

- DBQ - Economic Opportunities in The Colonial PeriodDocument3 paginiDBQ - Economic Opportunities in The Colonial PeriodPatrick PanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sepoy Rebellion Lesson Plan - 0Document13 paginiSepoy Rebellion Lesson Plan - 0margaritaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 15 Apush Period2 Kingphilip PrimarysourceDocument2 pagini2014 15 Apush Period2 Kingphilip Primarysourceapi-263088756Încă nu există evaluări

- St. George’S Cross and the Siege of Fort Pitt: Battle of Three EmpiresDe la EverandSt. George’S Cross and the Siege of Fort Pitt: Battle of Three EmpiresÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Thgrade Social Studies Sample QsDocument20 pagini5 Thgrade Social Studies Sample QsNarender DhamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The United States Enters the World Stage: From the Alaska Purchase through World War I, 1867–1919De la EverandThe United States Enters the World Stage: From the Alaska Purchase through World War I, 1867–1919Evaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (1)

- The American War of Independence Trivia ChallengeDe la EverandThe American War of Independence Trivia ChallengeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 7 History Teacher's Guide Fall of New France: Overall ExpectationsDocument9 paginiGrade 7 History Teacher's Guide Fall of New France: Overall ExpectationsDARK MOONLIGHTÎncă nu există evaluări

- AP US History Summer Assignment 2011 2012Document6 paginiAP US History Summer Assignment 2011 2012James OsumahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forgotten Warriors- Forgotten Battles: The Thirteen Revolutionary militias and their Indispensable RoleDe la EverandForgotten Warriors- Forgotten Battles: The Thirteen Revolutionary militias and their Indispensable RoleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apush-Chapter 2 Study GuideDocument1 paginăApush-Chapter 2 Study Guideapi-236043597Încă nu există evaluări

- Practice Exams Test 2 - Keys - Introduce British & American StudiesDocument7 paginiPractice Exams Test 2 - Keys - Introduce British & American StudiesPhụng LâmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Broadsides and Bayonets: The Propaganda War of the American RevolutionDe la EverandBroadsides and Bayonets: The Propaganda War of the American RevolutionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- The United States in World War II: 1941–1945De la EverandThe United States in World War II: 1941–1945Evaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- American Warfare in the Pre-Civil War Era: A 59-Minute PerspectiveDe la EverandAmerican Warfare in the Pre-Civil War Era: A 59-Minute PerspectiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mississippians in the Great War: Selected LettersDe la EverandMississippians in the Great War: Selected LettersÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 8Document3 pagini7 8Ekaterine ChachibaiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The U.S.A. History and Literature: from the beginning to the 20th centuryDe la EverandThe U.S.A. History and Literature: from the beginning to the 20th centuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Victory With No Name The Native American Defeat of The First American Army (PDFDrive)Document225 paginiThe Victory With No Name The Native American Defeat of The First American Army (PDFDrive)Zoltán Vass100% (1)

- War Along the Wabash: The Ohio Indian Confederacy's Destruction of the US Army, 1792De la EverandWar Along the Wabash: The Ohio Indian Confederacy's Destruction of the US Army, 1792Încă nu există evaluări

- The History of the Five Indian Nations Depending on the Province of New-York in America: A Critical EditionDe la EverandThe History of the Five Indian Nations Depending on the Province of New-York in America: A Critical EditionEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (8)

- Armies of Early Colonial North America, 1607–1713: History, Organization and UniformsDe la EverandArmies of Early Colonial North America, 1607–1713: History, Organization and UniformsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Uncommon Defense: Indian Allies in the Black Hawk WarDe la EverandUncommon Defense: Indian Allies in the Black Hawk WarEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- American Battlefield of a European War: The French and Indian War - US History Elementary | Children's American Revolution HistoryDe la EverandAmerican Battlefield of a European War: The French and Indian War - US History Elementary | Children's American Revolution HistoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Empire and Liberty: American Resistance to British Authority 1755–1763De la EverandEmpire and Liberty: American Resistance to British Authority 1755–1763Încă nu există evaluări

- CH 5-8 ApushDocument20 paginiCH 5-8 Apushapi-236312482Încă nu există evaluări

- American Revolution Term Paper TopicsDocument6 paginiAmerican Revolution Term Paper Topicsdajev1budaz2100% (1)

- Honors U.S History Unit Portfolio Project Michelle Voykovic Allatoona High SchoolDocument43 paginiHonors U.S History Unit Portfolio Project Michelle Voykovic Allatoona High Schoolapi-305492195Încă nu există evaluări

- AP Study NotesDocument18 paginiAP Study NotesChrisay ZhangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 4 The Seven Years' War, 1756-1763Document3 paginiLecture 4 The Seven Years' War, 1756-1763Aek FeghoulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture Up IntDocument20 paginiCulture Up IntLaura DryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revolutionary War Research Paper TopicsDocument6 paginiRevolutionary War Research Paper Topicsgw15ws8j100% (1)

- 17 ThcenturyfinalDocument238 pagini17 Thcenturyfinalcool1hand1lukeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class: XI Topic Subject: HISTORYDocument5 paginiClass: XI Topic Subject: HISTORYBhanu Pratap SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- The American Revolution: Experience the Battle for IndependenceDe la EverandThe American Revolution: Experience the Battle for IndependenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- A History of BritainDocument3 paginiA History of BritainFrancisco Cunha50% (2)

- Anglicizing America: Empire, Revolution, RepublicDe la EverandAnglicizing America: Empire, Revolution, RepublicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land Acknowledgment BackgrounderDocument2 paginiLand Acknowledgment BackgrounderDave OstroffÎncă nu există evaluări

- UnityDocument23 paginiUnityAlto SaxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Little Wolf: Red CloudDocument20 paginiLittle Wolf: Red CloudHelen KimotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Migration Pattern PPT 2Document20 paginiMigration Pattern PPT 2jerome_weir100% (1)

- Duran Merk Villa Carlota PDFDocument150 paginiDuran Merk Villa Carlota PDFIanuarius Valencia ConstantinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Indian Tribes of North AmericaDocument748 paginiThe Indian Tribes of North Americasubhan Utman khelÎncă nu există evaluări

- US History - Exam #1Document14 paginiUS History - Exam #1Siri BandamÎncă nu există evaluări

- AP US Outline Chapter 1 - New World BeginningsDocument4 paginiAP US Outline Chapter 1 - New World BeginningsSkyler Kessler100% (4)

- Maipuri Nation CharterDocument4 paginiMaipuri Nation CharterTushkahumoc Xelup100% (2)

- m595 Indian Census RollsDocument28 paginim595 Indian Census RollsSaroya Fanniel75% (4)

- The Cambridge Economic History of The United States Vol 01 - The Colonial Era PDFDocument461 paginiThe Cambridge Economic History of The United States Vol 01 - The Colonial Era PDFMolnár Levente0% (1)

- Chapter 2 - Trans Plantations & BorderlandsDocument6 paginiChapter 2 - Trans Plantations & BorderlandsDavid W.100% (2)

- De La Maza - Lo Indígena Como Categoría Censal - 2014Document19 paginiDe La Maza - Lo Indígena Como Categoría Censal - 2014Jorge Iván Vergara del SolarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09.2 Burkhart The Slippery Earth 1989Document128 pagini09.2 Burkhart The Slippery Earth 1989ruben_nahuiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amazonia: Linguistic History: Alexandra Y. AikhenvaldDocument8 paginiAmazonia: Linguistic History: Alexandra Y. AikhenvaldJoseOrsagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hemispheres Colliding Reading QuestionsDocument4 paginiHemispheres Colliding Reading QuestionsLisa TalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mintz-Caribbean As A Sociocultural Area PDFDocument16 paginiMintz-Caribbean As A Sociocultural Area PDFRaúl David LópezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burrows Cave SagaDocument58 paginiBurrows Cave Sagattreks100% (1)

- 100 Images HISTORY PROJECT - 1Document120 pagini100 Images HISTORY PROJECT - 1JUN CARLO MINDAJAO100% (8)

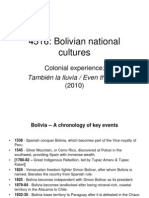

- 4516: Bolivian National Cultures: También La Lluvia / Even The RainDocument7 pagini4516: Bolivian National Cultures: También La Lluvia / Even The RainJaime Omar SalinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edward CurtisDocument15 paginiEdward CurtisBernardas Janauskas100% (1)

- Unveiling The Tapestry of Native Americans Unearthing Rich History, Culture, and ResilienceDocument2 paginiUnveiling The Tapestry of Native Americans Unearthing Rich History, Culture, and ResiliencePepe DecaroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carlos Fausto - Warfare and Shamanism in Amazonia-Cambridge University Press (2015) PDFDocument363 paginiCarlos Fausto - Warfare and Shamanism in Amazonia-Cambridge University Press (2015) PDFPaulo BüllÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Petitioners by State: (Bad Address)Document51 paginiList of Petitioners by State: (Bad Address)Ty Pack ElÎncă nu există evaluări

- Native AmericanDocument22 paginiNative Americanmahabekti0% (1)

- Homelands Essay MasterDocument9 paginiHomelands Essay Masterapi-680624821Încă nu există evaluări

- American History AP: Chapter 1 - NotesDocument3 paginiAmerican History AP: Chapter 1 - NotesAmanda PriceÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mesoamerican CivilizationDocument25 paginiThe Mesoamerican CivilizationJose RosarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1823 Treaty of Moultrie CreekDocument2 pagini1823 Treaty of Moultrie CreekChris MaceyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summer Reading AssignmentDocument10 paginiSummer Reading AssignmentAustin ClydeÎncă nu există evaluări